Paying racialized workers less than white workers was a longstanding practice in BC. Cheap labour was fundamental to the profits of the owning class, as were the requirements for long hours and the most dangerous tasks common to many new immigrants.

Sardara Gill said when he arrived at Fraser Mills in 1925:

“…for wages there was a five cent difference between us and white people. We got 25 cents an hour and the whites got 30 cents for the same job. My dad was pulling lumber on the greenchain, it was hard work. We’d start at 8 o’clock and finish at 5 o’clock. Sometimes I did 5 hours overtime, 13 hours a day. Most Saturdays and Sundays I worked as well, so 7 days a week. We did not get paid overtime in those days.” [1]

Legendary socialist couple Grace and Angus MacInnis saw through the deceptive racism of the regulation:

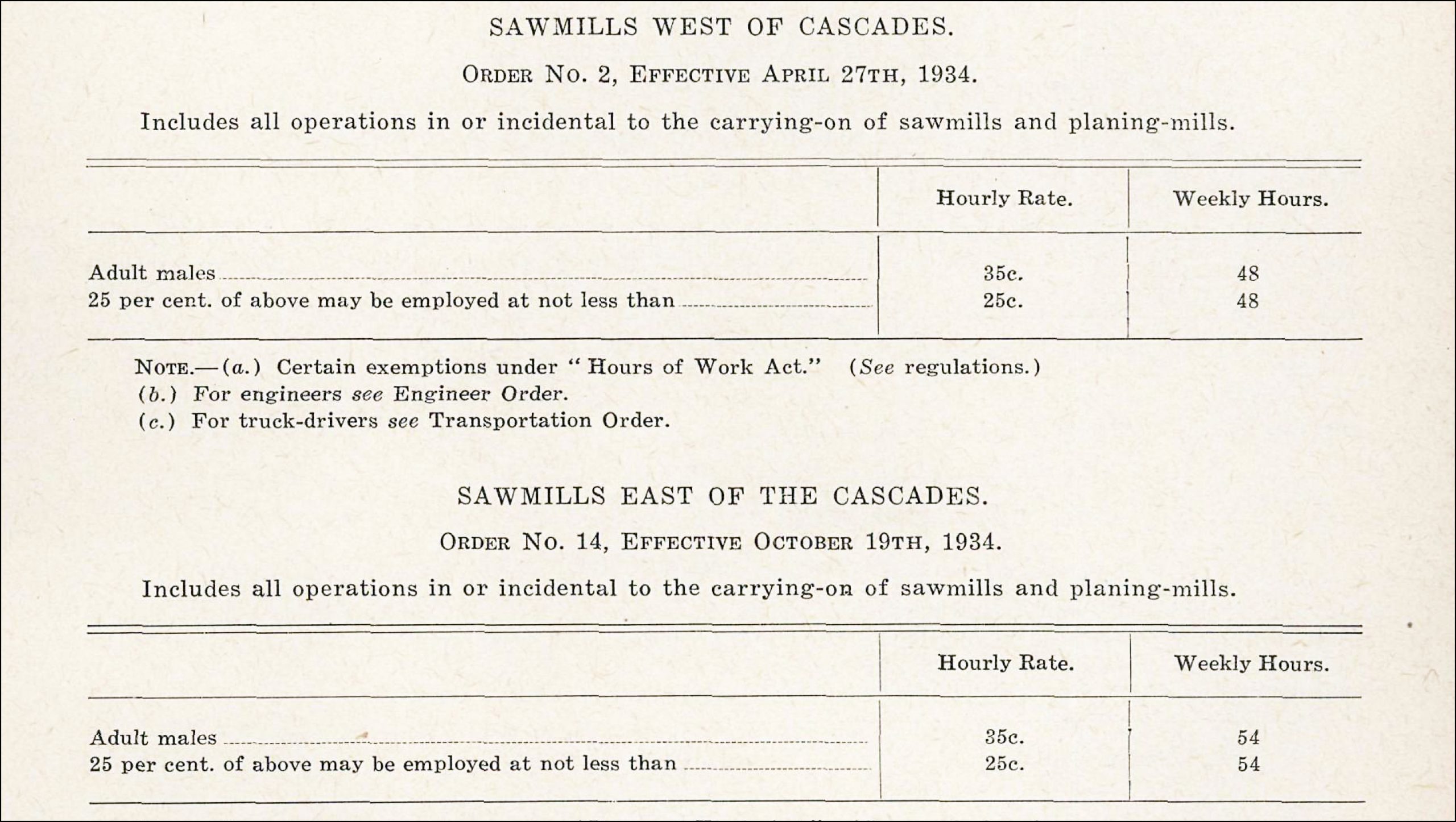

“In 1934 the British Columbia Board of Industrial Relations issued a minimum wage order for the sawmill industry which made it possible for an employer to hire up to 25 percent of his workers at wages of 25c an hour while those of the rest are fixed at 35c. In practice, this 25 percent has frequently been Oriental. Always the story has been the same. In good times the anti-Oriental feeling abates; in depressions it becomes acute. Its curve has very little to do with the color of the skin or the slant of the eyes; it is mainly economic.”[2]

“The government came in with a law in the mid-1930s which said that the minimum wage would be 35 cents an hour. But they could pay 25 percent of their employees 25 cents an hour. This was another form of discrimination because in every mill about a quarter of their workers were Asiatics…But Alberta Lumber Company was in a quandry because they employed about half Asiatics. And where were they going to draw the line among the Asiatics?”

“Whoever was the boss at the time got this bright idea. He’d pay the whites 35 cents a hour. When he came to Asiatics, he’d pay half of them 25 cents an hour. For the other half he made out cheques at 35 cents an hour but he’d come to the bunkhouse and get us to endorse our cheques, take them back and give us an envelope of money which was figured at 25 cents an hour. I couldn’t stand that you know, that was going a little too far. So I quit and got a job here at Hillcrest where they paid 35 cents an hour.” [3]

- Sarjeet Singh, An oral history of the Sikhs in British Columbia, 52. ↵

- Grace MacInnis and Angus MacInnis, "Oriental Canadians, Outcasts or Citizens?" Vancouver: Federationist Publishing, 1943, 8. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0354904 ↵

- Karm S. Manak quoted in Sarjeet Singh Jagpal, Becoming Canadians: Pioneer Sikhs in Their Own Words. Vancouver: Harbour Publishing, 1994, 144. ↵