World War II was a turning point for labour in Canada.

Governments saw the need to avoid the class turmoil sparked by World War I and end their standoffish approach of the Depression. Political expedience required reform. Labour’s decades long demand for federal unemployment insurance was realized in 1940. Universal family allowances were introduced in 1944. And at long last, after seventy years of struggle, the fight for compulsory recognition of unions and collective bargaining was finally won, first in British Columbia and then across Canada. In 1943, amendments to BC’s flawed Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act gave the government authority to recognize a union and force employers to bargain.[1]

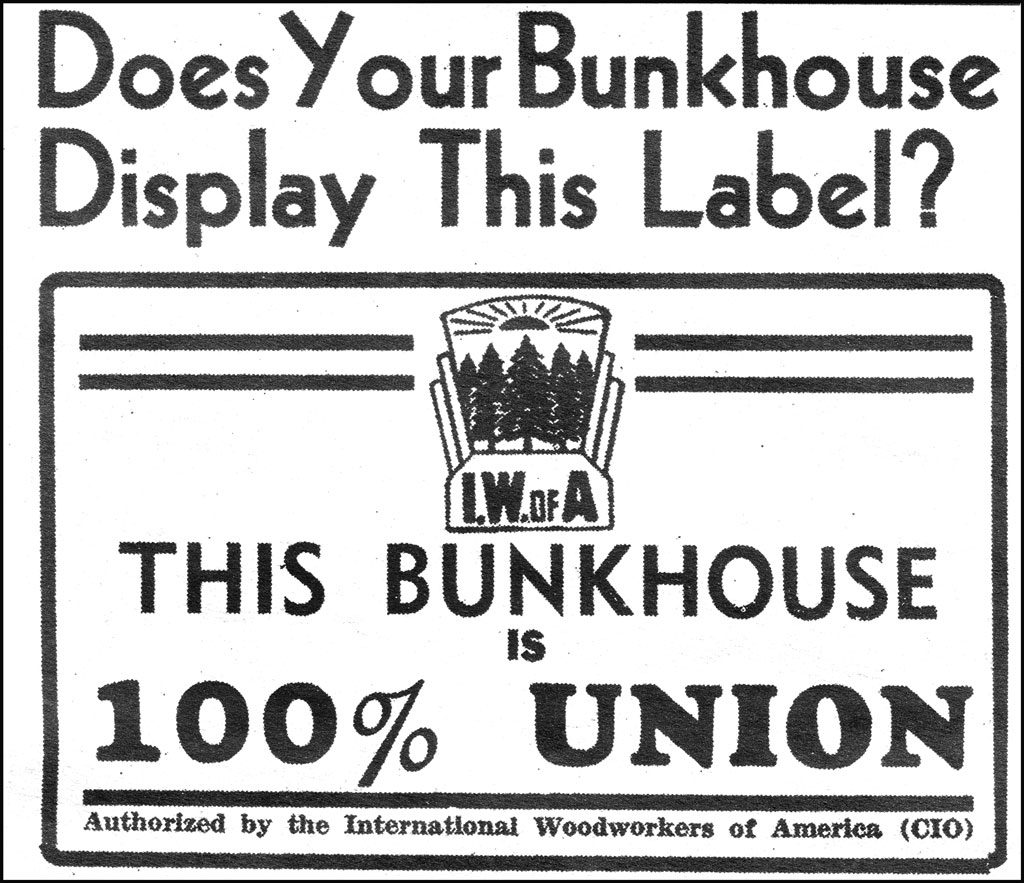

At the start of World War II the dominant union for lumber workers in BC was the International Woodworkers of America (IWA). A disastrous strike in 1938 drained the IWA’s resources and its membership numbered just a few hundred. It had no contracts in place and the future seemed bleak.

As a strategy to revive the union, the IWA leadership embraced new organizing strategies to encourage membership and involvement from South Asians, and other ethnic workers. The fight against fascism created a wartime labour shortage, and the willingness of government to concede union recognition meant organizing took off. South Asian Canadians, reluctant to join the war effort while still denied the vote, were still a significant part of the sawmill workforce.

In early December 1943, District Council No. 1 of the IWA signed its first coast-wide forest agreement, a one-year deal covering eight thousand employees in twenty-three camps and mills. The agreement recognized the IWA as the bargaining agent for the workers, ending the reign of labour contractors. Through this successful collective agreement, the union achieved an 8-hour day and 48-hour week as well as seniority provisions that guaranteed equality of treatment.

By the end of 1946 the IWA was the third-largest union in Canada with more than 25,000 members. Thousands of South Asians were already employed in the lumber industry. .

These first agreements were also the death knell of discriminatory, racially based wages in sawmills. This was a major shift; a generation-spanning dedication to the IWA from South Asian lumber workers took root in this period.

Technological change in the forest industry, which began in the 1970s impacted workers dramatically. Job loss hit the South Asian Canadian workforce hard. It was not until 1979 that the IWA managed to negotiate a joint pension plan that provided income security to workers forced out of the industry.

- Mickleburgh, On the Line, 106. ↵