4

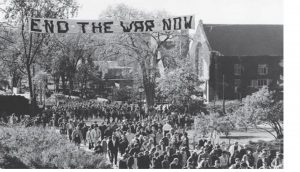

At the end of August 1968 Mai and I departed Virginia for our new home; Ithaca, New York. After four years in Vietnam, capped off by the turbulence of the Tet Offensive, I was looking forward to a contemplative interlude to reflect on what I had experienced, and attempt to gain the knowledge to understand it better and put it into perspective. Although I had a vague sense that this would eventually culminate in a teaching career, which would allow me to research, write, and pass on whatever I had learned from the Vietnam experience, my immediate goal was gaining the intellectual tools to gain a deeper understanding of what I had just gone through.

An even more important attraction of academia was the freedom to pursue a self-selected intellectual agenda, as opposed to the think-tank world dependency on external funding sources from organizations and institutions with a self interested objective. As I would soon discover, this ivory tower interlude was far more prolonged than I had anticipated, and the learning would take place in an environment that was quite different from the calm, placid, contemplative haven I expected that Cornell University would provide. In addition, there were many academic hurdles that had to be surmounted before reaching the promised land of control of one’s own intellectual direction.

We had packed all our worldly possessions that had been sent back from Vietnam in 1967 and put in storage in various outlying chicken coops at the farm while we were in Taiwan. Our first automobile was an Opel Kadet station wagon which I had purchased in Washington on the basis of reviews in Consumer Reports. Unwittingly I had added to the burdens of living in an isolated outpost like Ithaca, because there was only one Buick-Opel dealer within 50 miles, which charged cutthroat prices for the hard-to-get parts for the Opel, which were never in stock. The frequent repairs were a constant drain on our meager budget.

But we couldn’t know this as we set off from Washington with a spirit of adventure, somewhat dimmed by the fact that someone broke into our fully loaded car while it was briefly parked across from the National Gallery of Art, wondering what this new chapter of our life would bring. Fortunately the only casualty was the small transistor radio that had given me a life-long affliction with tinnitus in the Philippines.

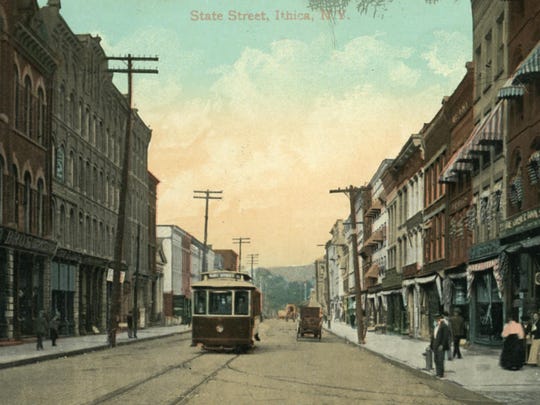

After a grueling journey, we finally arrived at the outskirts of Ithaca and began to descend the steep slope of State Street (Route 79) into the town. As we were about halfway down the steep incline, the vista of downtown Ithaca unfolded before us. It was a depressing shock to see what looked like the ruins of a derelict nineteenth century settlement of decaying brick factories and a desolate main street which looked like a ghost town. I still remember the exact location on State Street where this vision of our future was revealed to us. In the 2010 photo below, you can see the vista, but the dramatically transformed buildings reflect the extensive change in the profile of the town that has occurred in the last half century. In 1968 there were few buildings taller than three or four stories, and the construction materials were all early-twentieth century brick.

Ithaca 2010. The photos below give some indication of our first view of downtown Ithaca.

State Street, downtown Ithaca 1911

As can be seen from the photo below, there had been little change to the face of the main street in town over the course of the first half of the 20th Century, except for the additional traffic.

We looked for a place to eat lunch. There were a few lunch counter establishments but we chose the one chop-suey restaurant in the entire town, located on State Street, where we had an inedible lunch – a far cry from the cosmopolitan restaurant scene of Ithaca today.

There was no getting around it. We would be stuck in this dump for the foreseeable future. However, as we regrouped and began to explore the surrounding areas, we discovered that “far above Cayuga’s waters” the university itself was stately and scenic.

We had only a week to get settled before the fall semester opened, and it quickly became apparent that at this late date there were no decent apartments available. This turned out to be a blessing in disguise, because it forced us to turn to the alternative of actually buying a house. On the one hand, it was a big risk because I did not know if I would survive even one semester at Cornell. But on the other hand it turned out to be a godsend, when my “ivory tower interlude” stretched into nearly a decade. In the (thankfully brief) periods between the support of grants, stipends, the G.I. Bill and teaching salary at the end, living in inexpensive housing sustained us through some hard financial times as my “interlude” dragged on.

It also turned out to be a good investment of the modest savings we had accumulated while living a Spartan life in Vietnam. With the help of our realtor Peggy Lush (who later became a mainstay as administrative assistant of the Southeast Asia Program), we found an oddball property, that was within walking distance of both the Cornell campus and downtown Ithaca, and nestled on a small hill surrounded by hundreds of acres of woods. It had been nurse’s cottage attached to the hospital, but was somehow moved across Six Mile Creek, which separated Giles street from State Street, a connector between the campus and downtown, and maneuvered onto a small rise into its hillside perch. Although the stairs proved treacherous in the winter, the elevation meant privacy and minimal traffic noise.

There was no garage, and our parking was a slope next to the house which became slick in the winter from the water seeping from the hill above the house which turned into ice. In the freezing winter weather of Ithaca, we’d have to scrape the ice off the windshields front and back each morning, and we’d pray that the car would start. Eventually, we inserted a rod plugged into an outlet in our basement to keep the engine from freezing over during the night.)

At a price of $12,000 I managed to put down nearly $9,000 of our savings and pick up the existing mortgage at an interest rate of about 2.5%. The monthly payments were about $90 dollars, which made life affordable for us. (In 1977 we sold the house for about $35,000, a good return on our investment and one which made it possible to adjust to the sticker shock of real estate in California).

Moving to upstate New York was a shock for Mai. Ithaca was a lot colder and icier than Georgetown where she’d gone to college. The first winter, we were caught off guard by a blizzard in mid-October. We didn’t have snow tires and slid and swerved our way down the many slopes from the Cornell campus to our house. When we got home, we fought our way to our front door through several feet of accumulated snow. Our legs sank deep into the snow up to our knees with each step, and our feet clad only in flimsy shoes became numb. Mai was so miserable she failed to appreciate the stark, white beauty surrounding us.)

A University in Transition

Even if I had known more about Cornell when I arrived, I would not have been able to see immediately that it was a university in transition. Change is never fully apparent when you are in the middle of it. The university itself was in tension between the traditional ideal of the liberal arts university, the more recent vogue for a “multiversity” more closely attuned to the practical needs of society, and an engaged university attempting to transform society rather than merely reflect on it or transcend the mundane and retreat into the realm of ideas and contemplation. To some extent higher education had always reflected a tension between these conceptions of the university, but in the mid and late 1960s these tensions had escalated. Cornell, like other universities at this time was a pressure cooker about to blow – hardly the contemplative haven that I had envisioned.

The traditional vision of an “ivory tower” liberal arts university had been articulated by John Henry Newman in the mid-19th century. Newman was a British clergyman and Oxford academic who “gave a series of lectures in 1852 reflecting on the university’s purpose that were published as The Idea of a University in the same year. …For Newman, the ideal university is a community of thinkers, engaging in intellectual pursuits not for any external purpose, but as an end in itself. Envisaging a broad, liberal education, which teaches students “to think and to reason and to compare and to discriminate and to analyse”, Newman held that narrow minds were born of narrow specialisation and stipulated that students should be given a solid grounding in all areas of study. A restricted, vocational education was out of the question for him. Somewhat surprisingly, he also espoused the view that universities should be entirely free of religious interference, putting forward a secular, pluralist and inclusive ideal.”1

Cornell seemed to be headed in this direction under the leadership of its president Edmund Ezra Day in the early years following the end of World War II. Day cited its unique physical environment as a distinctive feature of the university, alluding not only to its beautiful physical environment but, probably, to its isolation, which reinforced the sense of community and status as an “ivory tower” enclave.

There were not many distractions from life at the university, especially in the long winters of Ithaca. A history of Cornell writes that “Many members of the faculty respected Day’s seriousness and fairness, his zeal for social betterment, and his devotion to Cornell. They were impressed when he turned down a request in 1946 from the State and War Departments to head the program of reeducation in postwar Germany, a position subsequently accepted by Harvard’s president, James Bryant Conant. Robert Cushman, a professor of government, remembered at Day’s retirement the president’s courage in the face of claims that Cornell leaned too far left. “With tact and good temper, but with force and tenacity, he defended the principle of freedom of thought and freedom of speech on the campus and elsewhere,” Cushman wrote.”2

Pioneered by Clark Kerr, the Chancellor of the University of the California at Berkeley, the idea of the “multiversity” came into vogue in the 1950s and early 1960s. In the introduction to his book on the 1969 turmoil at Cornell, Donald Downs observes that this concept provided context for what was to come. In the early 1960s at “the same time that campus protest was increasing, universities such as Cornell were busy transforming themselves into the ‘multiversity’ … In The Uses of the University published a years before the Berkeley student movement that launched the student revolts in the ‘60s, Clark Kerr said the term “multiversity” replaced “university,” which ‘carried with it the older version of a unified ‘community of masters and students’ with a single ‘soul’ or purpose.” Kerr added that the new “Alma Mater” was “less an integrated and eternal spirit and more a split and variable personality.” Reflecting the ‘growth of specialization and expertise in the new mass society, the multiversity was a research-oriented institution with multiple functions, interests, and connections to society.”3

In some ways, Cornell’s Southeast Asia Program, with its stated purpose of producing useful expertise for Cold War America, and its sympathy to multidisciplinary integration of the social sciences was a reflection of the “research-oriented institution with multiple functions, interests, and connections with society.” But, as would soon become apparent, there was growing controversy over the uses to which this knowledge would be put. Moreover, the “multiversity contributed to student militancy because students viewed it as an integral part of the alienating, bureaucratic, industrial machine. Indeed, Kerr called the new university a ‘knowledge factory.’” Downs observes that “It is precisely this perception of the university (bureaucratic education without a human face) that led to the student revolt at Berkeley…”4

During the Cold War years Cornell enthusiastically piled on the band wagon of area studies – which is the primary reason I was attracted to its graduate program. Cornell became the leading institution in Southeast Asian Studies starting from the 1950s. The Rockefeller Foundation also helped make Cornell the world center for Southeast Asian Studies. “The foundation’s director, Charles Fahs, wrote to Acting President de Kiewiet in August 1950, suggesting that, since the center at Yale was “inadequate to meet national needs,, Cornell should consider ‘refocusing your oriental interests on Southeast Asian Studies.’” A month later Chinese specialist Knight Biggerstaff and Thai anthropologist Lauriston Sharp, both of whom had done intelligence work for the government during World War II, “submitted a laundry list memo of resources such a center would need and concluded by invoking Cold War imperatives: ‘Today our government and international agencies are trying to keep the region from falling under Russian control; yet we do not know enough about the region to formulate policy intelligently. Our Southeast Asia Program at Cornell is and would continue to be directed toward securing the information that is necessary for intelligent formulation of policy.’”5

It was not the senior professor Lauriston Sharp who shaped the Cornell Southeast Program, but the person who would become an important mentor for me, George McT. Kahin, then fresh out of graduate school, but already a veteran of the McCarthy battles. Under Kahin, Cornell’s Southeast Asia Program was the antithesis of a “faceless, bureaucratic, knowledge factory.” Indeed, its hallmark (and that of the Government Department) was a highly personalized one-on-one contact between professors and grad students. In contrast to Columbia and Berkeley which admitted large numbers of graduate students and largely left them on their own to sink or swim and weeded them out over time (ironic that I should have been rejected by them and accepted at Cornell), Cornell made every effort to maximize chances for success of its graduate students, which led to a much more nurturing educational experience. It’s acceptance of a prolonged progress toward the Ph.d (it took me eight years, including an interlude with Rand in Vietnam, to complete my Ph.d., and this was not considered unusual) was very much in keeping with the Straussian ideal of allowing time for the ‘leisurely life of the mind” to flourish. Although I was not initially among Kahin’s coterie of favored students, his personalized model of education set the tone for those government students with interests in Southeast Asia, and facilitated maximum flexibility in devising a graduate program, to the displeasure of some in the Government Department who wanted more uniform standards of disciplinary rigor.

Kahin strongly defended the advisory system in which a government Ph.d candidate would have a main advisor, and two others, one of which was frequently from another department or program. The student’s curriculum would be negotiated between the advisors, with each professor responsible for his/her area of expertise. This was a way of ensuring that there would be room for area studies courses and language training for graduate students in the government department. Needless to say, the advocates of standardizing political “science” requirements and a mandatory “scope and methods” course thought this customized approach lacked disciplinary rigor and was unacceptable, while for people like Kahin who favored deeper training in language and area studies this flexibility was essential. Fortunately, I was among the last graduate students in the Government Department to enjoy this dispensation. In practical terms this allowed me to continue my study of the Chinese language instead of taking a course in quantitative methods (which I probably would have failed).

As a graduate student of Owen Lattimore, one of the most prominent Asian specialists of the era, Kahin had organized Lattimore’s defense against McCarthy’s slanders. “In January 1951 the Rockefeller Foundation gave Cornell’s Southeast Asia Program $325,000 and in December 1954 another $500,000. The architect of Cornell’s preeminence in Southeast Asia studies was George McTurnan Kahin, who arrived to direct the program in July 1951. An expert on Indonesia, who had grown up in Seattle, Kahin had graduated from Harvard, received his PhD from Johns Hopkins, and would spend his entire career at Cornell, mentoring most of the world’s Southeast Asia specialists. Like [Physics Professor Hans] Bethe, Kahin became a political activist during the Cold War. An advocate of a more progressive American posture to the newly independent nations of Asia and a vocal critic of the Indonesian dictator Sukarno, Kahin became a victim of McCarthyite Washington. The State Department deprived him of his passport, but President Malott and the Rockefeller Foundation continued to support him. In May 1965 Kahin would lead one of America’s first ‘teach ins’ against the Vietnam War.”6

Kahin actually found some humor in the hysteria of the 1950s and recounts his experience going through customs on his return from a trip to England. His suitcase set off the Geiger wand of the inspector, who nervously shouted to his colleague “Hey, Jim, here’s a hot one!” George was immediately detained and his luggage carefully examined. It turned out that he had packed his suitcase full of back-scrub brushes, a product in which the British were unexcelled, because he could not find satisfactory substitutes in the U.S. The customs officials found this offbeat cargo suspicious but couldn’t pin down the devious uses to which these brushes might be put. The Geiger counter was presumably a false alarm. The picture of reserved and mild-mannered George Kahin being collared as a suspected “hot one” with a bomb in his suitcase disguised as scrub brushes left an indelible impression on me about his travails in the Cold War.

Using the Rockefeller Foundation’s “area approach,” Kahin’s SEA Program “cut across disciplinary boundaries, training specialists in the region’s economics, government, history, anthropology, and culture, and made extensive use of Cornell’s collection of research materials on the Far East. The program also had a research center in Bangkok, Thailand, where Cornell had strong links. More Thai had attended Cornell than any other American college or university. The program’s graduates became leading academic and governmental specialists on Southeast Asia, just as Cornell became the place where U.S. Foreign Service officers and personnel from other government agencies came to learn about the region’s languages, politics, cultures, and economics.”7

Kahin was a complex mix of Cold War critic and Establishment insider, which enabled him to raise large amounts of funds from the Ford and Rockefeller foundations, while at the same time using his platform as Director of the pre-eminent Southeast Asian Studies program in America to assail American policy toward Southeast Asia – Vietnam in particular. Kahin’s support of academic training for Foreign Service Officers reflected his conviction that working from within the establishment was an essential reinforcement of his public criticism. He was not doctrinaire in his dealings with Southeast Asian specialists with government or defense connections, which was fortunate for me when my application was being considered by Cornell. Indeed Kahin routinely invited former U.S. ambassadors to teach or lecture who had implemented or encouraged policies with which he profoundly disagreed, so that he would have a better foundation for his critical analysis of these policies. Some years later when Rand anthropologist Gerald Hickey applied for a position at his alma mater the University of Chicago in the early 1970s but was blackballed for his Defense Department sponsored research on the Montagnards, Kahin offered him generous support to continue his writing at Cornell.

Ben Anderson remarked on this in his memoir. “…there was a peculiar contingent for which Kahin was primarily responsible. A strong and thoughtful critic of American foreign policy, he was inclined to explain its stupidities and violence as resulting from simple ignorance. He therefore believed that one of the program’s missions was to enlighten the state. In those days [1960s] he had a wide set of contacts in Washington, and encouraged both the State Department and the Pentagon to send promising young officials and officers destined to serve in Southeast Asia to study at Cornell for a year or two, alongside the regular graduate students. I am sure this contingent was genuinely influenced by the Cornell experience, but not nearly as much as Kahin hoped. As the years passed, and especially during the Vietnam War, their numbers shrank drastically and they eventually almost disappeared.”8 In fact, some notable Foreign Service officers came to Cornell in the 1970s, including Tim Carney, who produced some valuable scholarship on Cambodia, David Kenney (1974) and Hal Meinheit (1976), both of whom had served in Vietnam. They were the exceptions however, and the government intake into the SEAP essentially ceased during Kahin’s final years there.

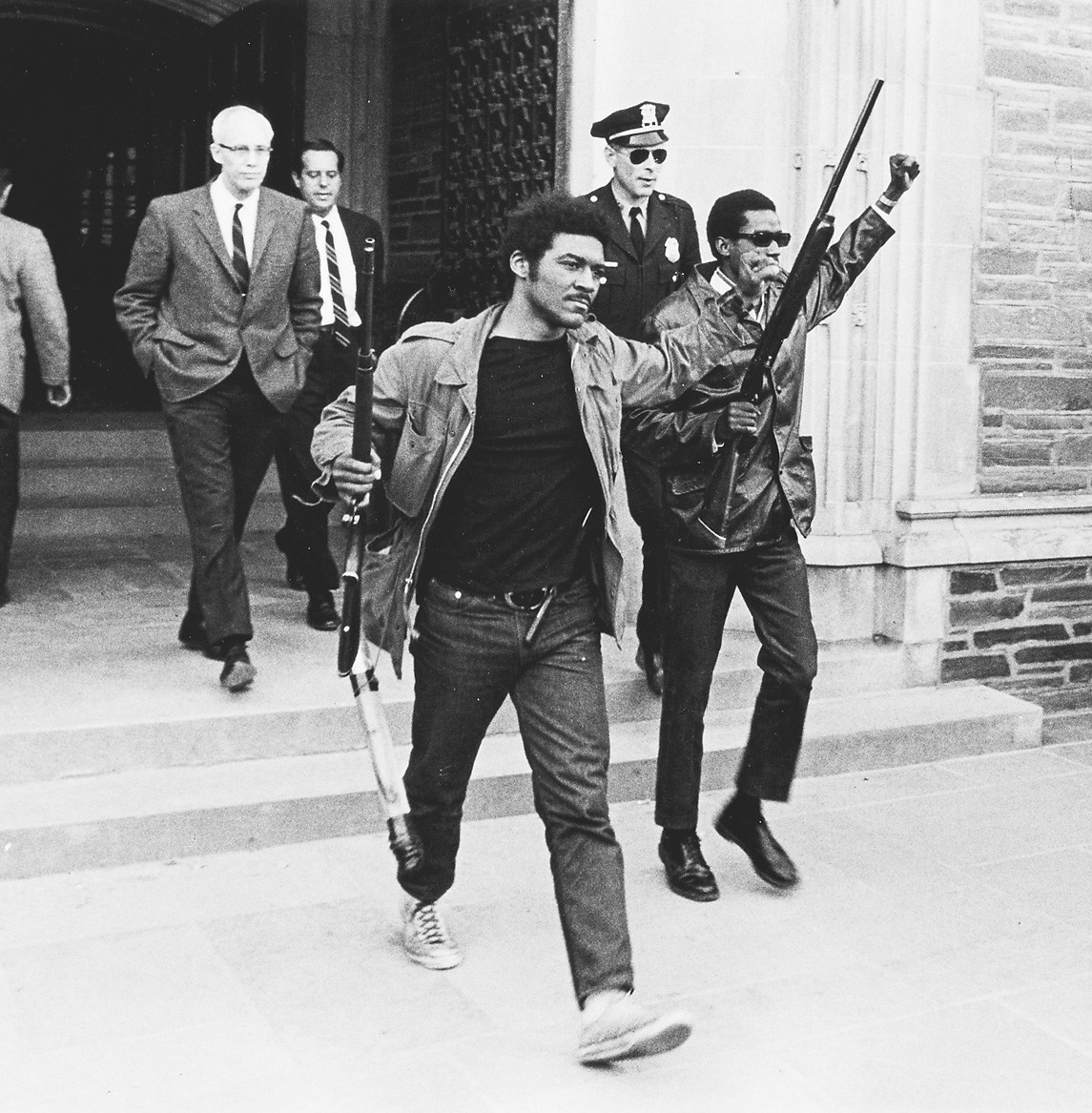

George Kahin was a rare example of a principled liberal who stuck to his guns during the turbulent late 1960s and stood by his unshakable commitment to the ideals of decency and academic freedom even as Cornell lurched toward an increasingly chaotic radicalization of the campus. The high point of his resolute and principled stand in Cornell’s time of troubles in the late 1960s, was his impassioned defense of academic freedom, discussed below, at a time when many of his liberal colleagues were simply swept aside by the seemingly unstoppable tide of radicalization.

My close association with Kahin did not develop until much later in my years at Cornell. My primary benefactor and mentor was David Mozingo, who had left Rand’s Social Science Department in 1967 to come to Cornell. He was the one who opened the door to my graduate study which made my subsequent professional career possible.

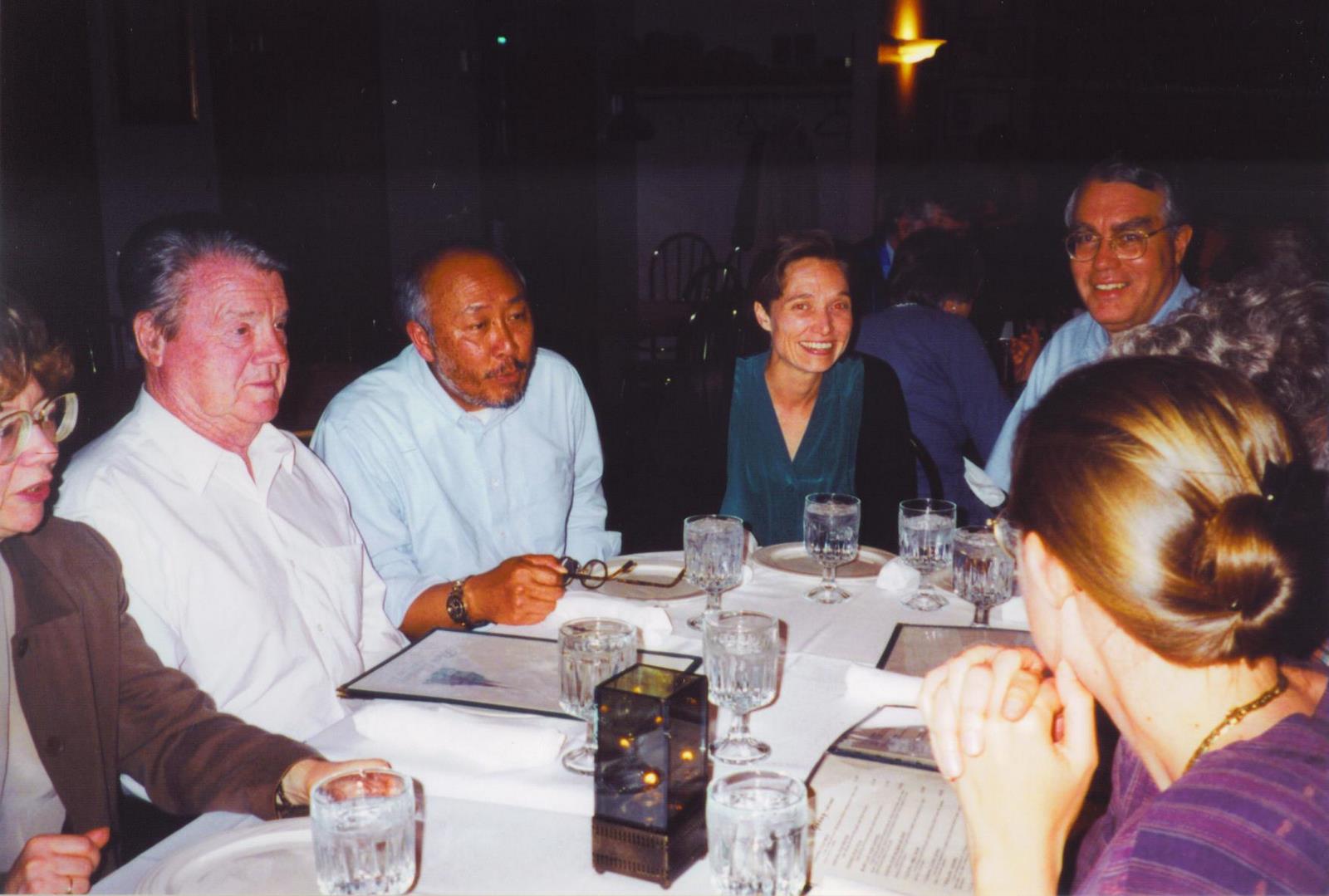

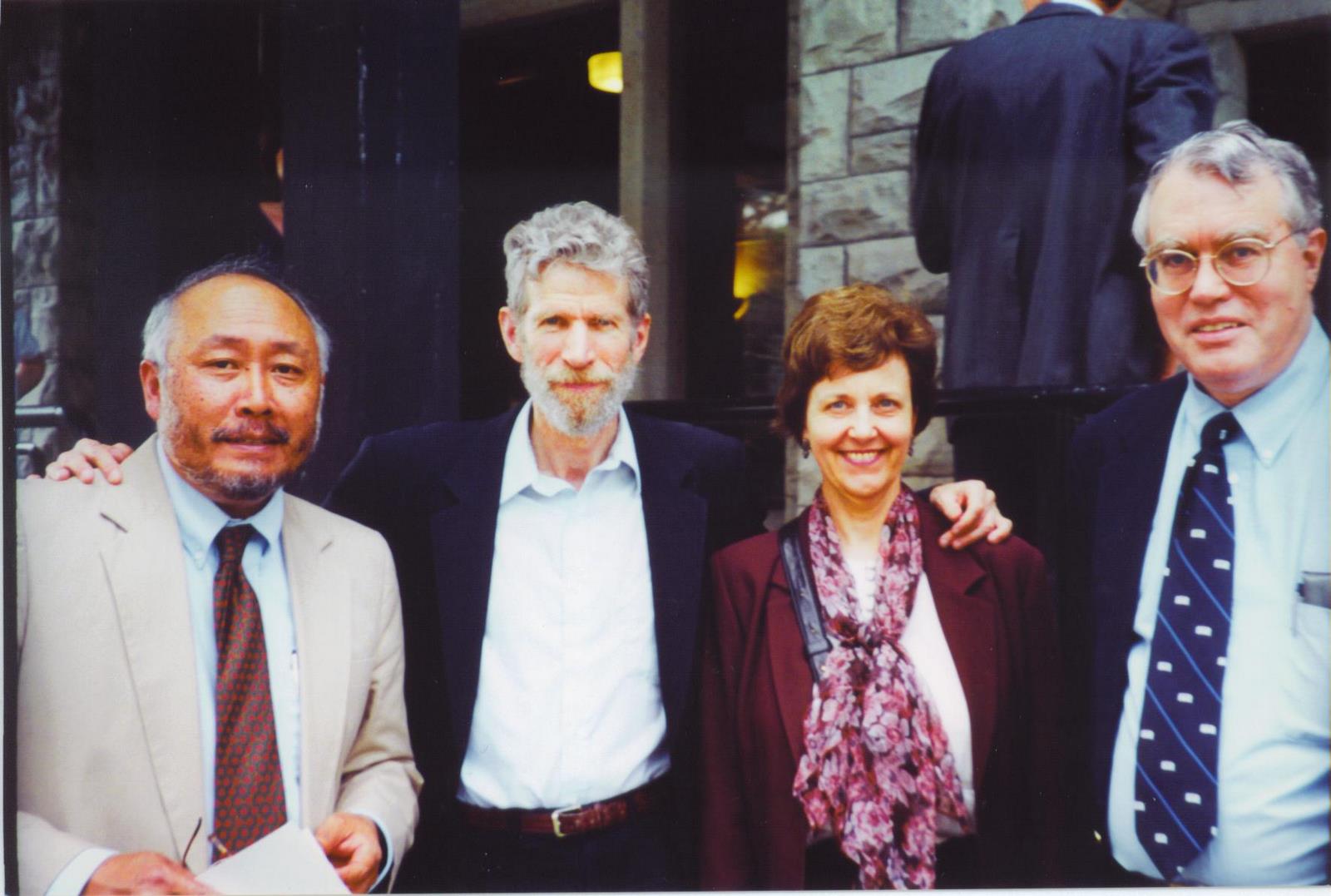

Three generations of Cornell academics at George Kahin’s memorial in 2000. DE is on upper right. Next to him is DE’s Pomona College advisee Tamara Loos, now a distinguished professor and Thai specialist in the Cornell History Department and became the first woman to serve as Director of Cornell’s SEAP in 2010. To her right is Thak Chaloemtiarana who came to Cornell the same year I did and has been a key participant in the SEAP administration for many years. David Mozingo is to his right, next to Laura Summers, a member of my graduate student cohort and a Cambodian specialist.

When I first arrived at Cornell, George Kahin was beleaguered and overburdened by administrative responsibilities. He had a few favored students who were close to him, but for most of us new arrivals George Kahin was a figure of Olympian remoteness, someone we encountered in occasional office visits, where he listened politely to whatever our business was, but made it clear that we were on the clock and needed to stay on point. A characteristic and memorable gesture was Kahin kneading his brow, as if beset with a splitting headache and overwhelming fatigue. Given his staggering workload and health problems, this was quite understandable. It also made my growing personal connection with him in the later years of graduate study all the more precious, as he divested himself of administrative burdens and, in a relaxed mood, displayed his wonderful wit and humor.

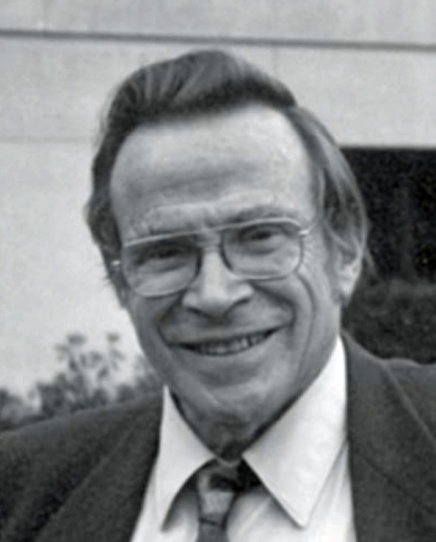

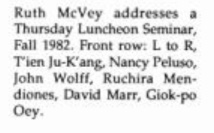

George Kahin, founding director of Cornell University’s Southeast Asia Program (SEAP)

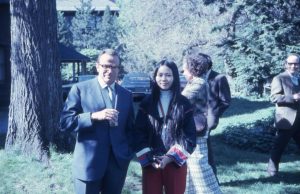

George Kahin and Mai at SEAP reception circa 1974.

His description of chasing himself in circles, retreating squeamishly from the hypodermic needle he held in his hand because, in the absence of doctors in rural Indonesia, he had to give himself an inoculation in the rear, was told with a self-deprecating dry wit that left his auditors in stitches.

It was David Mozingo, however, who did the heavy lifting, especially in his fastidious and brilliant editing of my prolix papers. His own work was a model of exceptional analytic reasoning, expressed with concision and clarity. Much as I benefited from his labors, which went far beyond the call of duty, I could never come close to the streamlined polish of his own work. It was David, too, who supported me for funding, especially in my years away from Cornell in 1971-1972 for dissertation research.

In addition to the courses I took from Kahin and Mozingo, I also took courses to cover the gaps in my political science education which had not been filled during two years at the University of Virginia’s Woodrow Wilson School of Foreign Affairs, which had split off from the Political Science Department. The most urgent task was getting up to speed in comparative politics, since I had concentrated mainly on international relations at U.Va. I greatly benefited from instruction from Myron Rush, a Soviet specialist who had also worked for Rand, and who was one of the most broadly educated persons I ever came across. His understated brilliance was not, in my view, sufficiently appreciated by either his colleagues or his students. I was fortunate to be taken on as a teaching assistant by Rush, though I’m afraid I did not pull my weight in his course. Mario Einaudi, who had a close personal connection with my father (which he never mentioned to me, and which I only discovered much later while examining my father’s papers in the Hoover Institution Arvchivers) was a brilliant scholar, and a key founder of the Center for International Studies at Cornell. And, of course, there was the towering intellect of Ben Anderson, though like the sun he shone too brightly for most graduate students to approach. As a favor to George Kahin he later agreed to be on my dissertation committee, but it was quite clear that he felt it was pretty pedestrian stuff. For some reason, Ben was not intellectually interested in Vietnam, possibly because it was not exotic or “Southeast Asian” enough, or perhaps simply because it had been “overexposed” and was no longer an esoteric subject. This was a rare exception to his otherwise omnivorous curiousity.

Cornell’s Government Department Enters It’s Time of Troubles

I alluded to the competing models of a university in play at Cornell during the 1960s and 1970s. Cornell’s Government Department reflected many of these tensions. First of all, the fact that, like Harvard, it stubbornly clung to the title “Government Department” rather than the more conventional “Department of Political Science” was a statement that its leading members had reservations about the behaviorist revolution that had swept the field in the 1950s. “Government” signified that the essence of the study of politics was examining governing institutions and policies, with a heavy emphasis on constitutions and legal systems whereas the political “scientists” preferred to focus on actual individual and collective political behavior. In the view of its “behaviorist” advocates, this approach required the use of quantitative methods to measure and analyze political behavior.

George Kahin, the central figure in the government department for people with interests in Southeast Asia, was very much a traditionalist, and focused heavily on institutions and political parties, as evidenced in the text book Government and Politics of Southeast Asia. Although many of his own colleagues viewed George Kahin as essentially a Southeast Asian expert who was more historian than political scientist, Kahin was acutely aware that in university politics, departments based on disciplines trumped all else. As his most prominent student, Ben Anderson (who received his Ph.d. in 1967 and joined the government department faculty the following year, observed, “[Lauristen] Sharp and Kahin were both intelligent academic politicians who recognized the power of disciplinary departments in American universities. They also understood, better than Peltzer and Benda at Yale [Karl Peltzer’s daughter Christine came to Cornell’s government department in 1967 and eventually wrote a thesis on land reform in Vietnam], that the long term growth and stability of Southeast Asia programs depended on new faculty being integrated, intellectually and financially, into these departments.” Kahin’s strategy was to use soft money from Ford and Rockefeller Foundations to grease the wheels for a promising Southeast Asian specialist for a few years. If all went well, the scholar would establish credible disciplinary credentials during this period and the rest of the department could then be persuaded to move the costs to the department’s regular salary budget.” Thus Anderson had to teach a number of courses on subjects unrelated to his expertise on Indonesia and Southeast Asia. I greatly profited from his popular course on “The Political Role of the Military.” “This involved a lot of work,” he acknowledged, “but it protected the program from lapsing into isolation and Orientalism. The crucial thing was that every professor in the program should have a firm base in a discipline, and be able to teach many more subjects than Southeast Asia.”9

Even with the strong support of David Mozingo, Martin Bernal who was brought in as a China specialist after the departure of John Lewis to Stanford, was accepted by the department only because of his encyclopedic knowledge of European politics. He may not have been a political “scientist” but his interest in and grasp of politics was extraordinary. Martin left an indelible impression on Sidney Tarrow with his effortless command of the minutia of Italian regional politics. Nevertheless, Bernal said in his memoirs that he received “more intellectual stimulation from Telluride than from the government department.”10

Later on in his memoir, Martin amended this judgment slightly, in paying tribute to some of his colleagues, like Isaak Kramnick and Sidney Tarrow. “Both became good friends and important intellectual stimuli. Later Isaac, while chair of the department, was extremely helpful in allowing me to shift my teaching gradually away from contemporary China and world revolutions to history and historiography. With Sid and many other members of the department, including Peter and Mary Katzenstein, all of whom have been good personal friends, I generally felt uneasy if not guilty, because while I have always been passionately interested in politics and I often enjoyed and gained knowledge from my colleagues conversation, papers, and publications, I cannot say the same of ‘political science.’”11 Just as Ben Anderson would make his enduring international reputation on the basis of “Imagined Communities” which owed little to the methodology of “political science,” Martin became famous for his controversial Black Athena, subtitled “The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization,” which was the culmination of his intellectual departure from the narrow disciplinary confines of his department. The fact that Cornell’s Government Department could tolerate such intellectual mavericks reflected its seriousness about the liberal arts framework in which the discipline of political science was situated.

Like Bernal at Telluride, George Kahin and supporters of the area studies approach often found themselves aligned with a group of political theorists who followed the approach of the legendary Leo Strauss, and were referred to dismissively by critics as “Straussians” and treated as though they belonged to a somewhat disreputable cult. This story is well told by Isaac Kramnik, a Government Department insider, but one who did not align with any of its factions. His account is worth quoting at length.

“NEARLY EVERYTHING WAS politicized at Cornell in the 1960s and 1970s. The Division of Biological Sciences was denounced by faculty from Government and History, led by Professor Allan Bloom, expressing contempt for those who had tampered with “the traditional structure of the University.” Bloom was “profoundly disturbed” that biologists assumed they could understand and control how genes and the environment produce people, and therefore that (more than humanists) they should “play that part not only as means to [finding] a better life but as one of the methods of determining what the good life is.” On the contrary, Bloom argued, biologists needed the wisdom of humanists to understand human nature and the good life, concluding ‘the biological sciences belong in the Arts College and not in splendid isolation.’ Bloom also opposed the six-year PhD program because it intended to take very bright high school students who had made ‘a firm career choice’ and ‘rush them through to the start of those careers,’ instead of letting them follow the ‘leisurely life of the mind.’ The intellectual leader of Cornell’s conservative faculty, Bloom was one of the most popular teachers at Cornell in the 1960s; students often burst into applause at the end of his lectures on the wisdom found in the ‘Great Books.’ In his early thirties, the charismatic Bloom, a follower of the political theorist Leo Strauss at the University of Chicago, gathered disciples of his own at Cornell, especially among students at Telluride House, where he had lived as a faculty guest for a year and a half. Created in 1911 with a gift from the Colorado Power Company entrepreneur Lucien Lucius Nunn, Telluride provided free room and board to carefully selected students—all of them men, until 1961—who ran the House cooperatively. The intellectual epicenter of Cornell in the 1960s, Telluride was divided into two camps—on the one hand the conservative followers of Bloom and his colleagues Walter Berns in Government and Donald Kagan and L. Pearce Williams in History, and on the other the more radical disciples of the literary theorist Paul de Man, who taught at Cornell until 1966 and spread the theories of Jacques Derrida, the French deconstructionist. In his 1987 best-selling polemic, The Closing of the American Mind, Bloom took Cornell as the model for what he saw as the decline of higher education. This landmark in the ‘culture wars’ of the last third of the twentieth century criticized the intense politicization of campus life in the ’60s. Faculty and ad-ministrators, Bloom claimed, ceased to see the purpose of a liberal education as finding truth and the nature of a good life. Their relativistic, value-free convictions led them away from the traditional obligation of philosophical professors to perceive objective good and objective evil and to transmit these truths to students. Instead, he lamented, students were left to construct their own curriculum as they sought to realize their own unique selves. Deferring to students as if public opinion finds truth, Bloom wrote, the faculty ‘no longer provide guidance as to what is important and no longer set standards based on a view of human perfection.’ The seemingly apolitical consensus on the merit of student course evaluations, introduced in the ’60s, epitomized the betrayal of Bloom’s vision of the university: ‘To assert that students, as a matter of principle, have a right to judge the value of a professor or what he teaches is to convert the university into a market in which the sellers must please the buyers and the standard of value is determined by demand.’ Among the much larger group of left-leaning faculty on campus, committed less to rational discovery of the good life and more to how the university could combat inequality, racism, and war, there was no counterpart to Bloom, no intellectually dominant personality serving as champion of a just and truly democratic university. Probably the closest claimant was the Economics professor Douglas Dowd, a central player in antiwar activities and racial politics in the 1960s. America in 1967, he told students in Anabel Taylor Hall, was ‘the very worst society that history has ever known,’ because it denied people ‘social justice, which means a world in which men can live decently and freely, in some sort of equality.’ The appointing and promoting of faculty were often politicized. The Government Department, dominated by Bloom and Berns, in an unannounced meeting just before Christmas in 1967, hired another Straussian political theorist from the University of Chicago, Werner Dannhauser. The action so enraged absent department member Mario Einaudi that he resolved never to participate in departmental affairs, and, indeed, he spent the rest of his career self-exiled in the Center for International Studies. After the suicide of Clinton Rossiter in July 1970, Arch Dotson, the chair of the Government Department, urged Corson to appoint Daniel Patrick Moynihan, professor of education and urban studies at Harvard and a former counselor to President Nixon, as John L. Senior Professor. Moynihan turned down the offer, but then changed his mind, by which time Corson had received strong expressions of disapproval from Walter LaFeber in History and Urie Bronfenbrenner ’38 in Human Ecology, who warned of an angry response by African American students over Moynihan’s proposed policy of ‘benign neglect’ to racial issues, crafted when he worked at the Nixon White House, and over his claims about “the pathology” of black families. Corson declined to renew the offer to Moynihan, who was later elected to the United States Senate. For this reason, Corson indicated, “for many years I had strained relations with the Senator.” Theodore Lowi, a distinguished liberal political scientist from the University of Chicago, who had taught at Cornell earlier in the 1960s, was given the Senior chair a year later, despite Mrs. Senior’s letter reminding Corson that she hoped that Clinton Rossiter’s replacement “will present the conservative point of view to the students.’”12

This account gives some sense of why the behaviorist revolution did not take hold at Cornell, fortunately for me, since I would have been hopeless at employing rigorous quantitative methods to my research. It is easy to see why the area studies advocates in the Government Department, led by George Kahin, made common cause with the Straussians. Both opposed the narrow professionalization of political “science” and the Straussians did not object to the interdisciplinary eclecticism of area studies advocates.

The impact of Foucault was beginning to be felt especially in places like Telluride, and the emergence of what would become known as “constructivism” was dimly visible. The connection between SEAP’s emphasis on language and indigenous perspective and these new trends is evident in this brief summary of the Foucault impact in Wikipedia: “Besides focusing on the meaning of a given discourse, the distinguishing characteristic of this approach is its stress on power relationships. These are expressed through language and behavior, and the relationship between language and power. This form of analysis developed out of Foucault’s genealogical work, where power was linked to the formation of discourse within specific historical periods. Some versions of this method stress the genealogical application of discourse analysis to illustrate how discourse is produced to govern social groups. The method analyzes how the social world, expressed through language, is affected by various sources of power. As such, this approach is close to social constructivism, as the researcher tries to understand how our society is being shaped (or constructed) by language, which in turn reflects existing power relationships. The analysis attempts to understand how individuals view the world, and studies categorizations, personal and institutional relationships, ideology, and politics. The approach was inspired by the work of both Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida, and by psychoanalysis and critical theory. Foucauldian discourse analysis, like much of critical theory, is often used in politically oriented studies. It is preferred by scholars who criticize more traditional forms of discourse analysis as failing to account for the political implications of discourse ”13

To me, Ben Anderson’s most original intellectual contribution was his brilliant essay “The Idea of Power in Javanese Culture” which may owe something to these emerging trends. It was certainly a landmark in the political analysis of a Southeast Asian society and tradition. His discussion of how he came to write this is one of the highlights of his autobiography.14 The importance of close textual analysis was stressed both by Straussians, and George Kahin who, along with David Mozingo, insisted on such close analysis of political documents in order to discern the underlying intent. Kahin’s obsession with textual evidence and documentation stemmed from a lifetime of defending himself (and others, like Owen Lattimore) against baseless charges that needed to be rebutted with authoritative facts and accurate accounts of the words and actions of America’s enemies on the other side of the Cold War divide. This sometimes led to a pedantic and documentarian style to his writings, such as his best known book on America and Vietnam, which often read like a legal brief for the defense. On the other hand, he was often taken to task by critics for not being sufficiently “academic.” However, the net result was that this book became an influential source for debunking much of the Kennedy-Johnson rationale for intervention in Vietnam. Some of Mozingo’s pathbreaking analyses took dead aim at debunking the preconceived notions embedded in official U.S. government analyses of Chinese communist writings.

Although “Foucauldian discourse analysis” was the farthest thing from my mind and, indeed was probably beyond my intellectual grasp, perhaps the most important lesson I learned at Cornell was simply the importance of understanding other cultures on their own terms. As I mentioned in the previous chapter, a grasp of the language is a necessary but not sufficient condition for this. I understood, for example, what the literal meaning of “the sun is spinning” as the crowd witnessing this phenomenon exclaimed just before the overthrow of President Diem, but not the portentous underlying signification that this freak natural phenomenon was understood by all Vietnamese as a signal of dramatic impending turbulent change.

The Perils of Cultural Empathy

In the 1950s Kahin stood out as someone who broke from the Western academic habit of viewing the colonial world through the lens of the colonial specialists who were regarded as the unchallenged authorities on the countries they had known through deep immersion over an extended period of time. The problem was that the colonial perspective, even when the colonial scholars were fluent in the local language, was inherently an external one, reflecting the biases of its purveyors. American scholars attempting to study Southeast Asia were handicapped by the linguistic barrier and thus reliant on these Western language sources. Not only were the indigenous languages, especially Vietnamese, usually quite difficult, there was little incentive to learn one language because it would be of limited value in the rest of the diverse region. So Western scholars inevitably resorted to writings in European languages for insights into the countries of the region.

Kahin had received training in Indonesian language during his stint in the army at the end of World War II, and finally got the opportunity to travel to that country in 1948. The result was his classic work of scholarship and reportage titled Nationalism and Revolution (1952), which was the first American academic study of decolonization in Southeast Asia based on direct observation, interviews with indigenous leaders, and vernacular sources. Indonesia’s foreign minister Ali Alatas later praised Kahin for having “tried to see things and evaluate events from the perspective of the Indonesian people themselves,” which he termed a “rare but welcome specimen” in contrast to some other Western researchers.15

To many critics of the Kahin/SEAP approach, the downside was that that the stress on seeing things from the indigenous point of view could lead to a credulous acceptance of self-serving rationalizations by tyrannical regimes, and the easy acceptance of the proposition that “to understand all is too forgive all” (tout comprendre c’est tout pardoner). Thus an attempt to understand the outlook that shaped Hanoi’s strategy toward South Vietnam, or its objectives in the Tet Offensive, could be read as an endorsement of their actions. Or, as happened later, an attempt to understand the reasons for the brutal Khmer Rouge forced evacuation of Phnom Penh in 1975 was regarded by some as an endorsement of this action or, at the least, turning a blind eye to the atrocities that were committed in the name of “national salvation.”

What began as an enlightened effort to explain and defend the nationalist point of view in the context of anti-colonial struggles, encountered increasing challenges as the dominant voice of the independence movement in various Southeast Asian countries inevitably fragmented into a cacophony of contending voices with different visions of “the indigenous perspective.” Indeed, I recall during my graduate school days at University of Virginia, before I knew anything about Vietnam, being irritated by the grandiosity of Gregory Nguyễn Tiến Hưng’s proclamations on behalf of “my people” – not on political or policy grounds but because I found it self-aggrandizing that anyone, especially a fledgling grad student in a foreign country, should arrogate to themselves the right to speak on behalf on an entire society, (Hưng – not to be confused with my close life-long friend Nguyễn Mạnh Hùng – note the different phonetic marking: “ư” – without a tone in the “u” of Gregory Hưng’s given name, as opposed to the straight “u” with a down tone in the name of Nguyễn Mạnh Hùng. I was unable to grasp the distinction until after I had spent 47 weeks studying Vietnamese at Monterey). Gregory Hưng later became the economic advisor to Nguyen Van Thieu in the waning days of the Saigon regime). When I knew him in the early 1960s, I doubted that he spoke for his two fellow Vietnamese graduate students, let alone the entire South Vietnamese people. I had first encountered this conceit at Yale, when I often heard my Latin-American roommates‘ wealthy and privileged friends speak expansively on behalf of “my people” and Gregory Hưng’s invocation of this trope sounded familiar.

The most controversial aspects of George Kahin’s writings on Southeast Asia included his analysis of the “bloodbath” theory, which downplayed the killings during North Vietnam’s land reform in the 1950s, as well as the extent of the murders of non-communists in Hue during the Tet Offensive. His endorsement of the even more controversial analysis by his student Gareth Porter of the Khmer Rouge brutal evacuation of Phnom Penh in 1975 was similarly based on a downplaying of Western accounts of these events. In due course persuasive local sources later proved him wrong. The problem, in these cases, was not overreliance on indigenous sources, but the reflexive rejection of local sources which appeared to reflect American views and interests, stemming from ingrained habit of rejecting critical accounts of local revolutionary movements by American government sources or local viewpoints from allies and clients on which they relied as inherently self-serving and not credible.

Toward the end of his career Ben Anderson reflected on the pitfalls of excessive empathy toward the indigenous point of view which privileged the perspective of those in power in the post-Independence era. “After the world wars of the twentieth century, however, many young nationalisms typically got married to greybeard states. Today [2014] nationalism has become a powerful tool of the state and the institutions attached to it: the military, the media, schools and universities, religious establishments, and so on. I emphasize tools because the basic logic of the state’s being remains that of raison d’état – ensuring its own survival and power, especially over its on subjects. Hence contemporary nationalism is easily harnessed by repressive and conservative forces, which, unlike earlier anti-dynastic nationalisms, have little interest in cross nationalist solidarities. One has only to think of state-sponsored myths about the national histories of China, Burma, both Koreas, Siam, Japan, Pakistan, the Philippines, Malaysia, India, Indonesia, Cambodia, Bangladesh, Vietnam or Sri Lanka for Asian examples. The intended effect is an unexamined, hypersensitive provinciality and narrow-mindedness. The signs are usually the presence of taboos (don’t write about this!, don’t talk about that!) and the censorship to enforce them.”16

Certainly this was an inherent problem with the cultural empathy approach, but the alternative was often an even more credulous retrofit of American concepts and fixations like the “Domino Theory” on the realities of Southeast Asia (Vietnam in particular), and the utter disregard of indigenous cultural factors which made Western colonial-era counterinsurgency schemes like the Strategic Hamlet program not only ineffective, but counterproductive. Indeed, as noted by Cornell’s current Southeast Asianist in the Government Department, Tom Pepinski, “The first principle of Southeast Asian studies is the very artificiality of the concept of Southeast Asia. I have called this the ‘fundamental anxiety’ of Southeast Asian studies — that there is no coherent argument why Southeast Asia properly includes Burma but not Bangladesh or Sri Lanka, or why it includes Indonesia but not Papua New Guinea, why Vietnam ought to fall within Southeast Asia rather than East Asia.”17

This insight is an obvious caution against glib generalizations about the region, such as the Domino Theory. The study of Vietnam at Cornell was strongly influenced by its placement in the Southeast Asian program. Harvard was assigned the task of examining Vietnam within the framework of its East Asia program by the terms of the same Ford Foundation grant which allocated funds for Vietnam to be studied within the framework of the Southeast Asia Program. This was another factor which made it unlikely that the idea of Vietnam as a puppet of China would be favorably received. Indeed, as events would soon demonstrate, the interests of Hanoi and Beijing in Southeast Asia were inherently in conflict. My own dissertation attempted to demonstrate how and why the very different revolutionary paths of China and Vietnam produced quite different regimes in the post Liberation/Independence period, underlining the improbability of Vietnam aspiring to become a tool or clone of China.

The key to a successful cultural empathy approach was to start with the “understanding” of the indigenous prospective, but to avoid invoking it as a blanket endorsement of the actions of one or another element of the society. In the case of Vietnam, this meant avoiding the assumption that only those who had actively resisted the French (the majority of them Vietnamese communists or sympathizers) were the “true” nationalists.

The sympathetic focus on the nationalist antecedents of the Viet Cong during the Kahin era led a new post-Vietnam war generation of scholars to chastise the Cornell scholarship on Vietnam during the 1960s and 1970s as shallow and polemical and, above all, sloppy and credulous. In the 1980s the first postwar revisionist wave of scholarship began by reassessing the colonial period to challenge the idea that only the Ho Chi Minh forces deserved historical recognition as “nationalists.” This was followed in the next decades by a revival of interest in the non-communist nationalists of the Saigon period (1954-1975), who some younger scholars regarded as more authentic representatives of Vietnamese nationalism than the Viet Cong and Hanoi with their Cold War alignments. Some scholars, like Keith Taylor even reject the notion that there was such a thing as Vietnamese nationalism – an idea which would have seemed bizarre during the Vietnam War years.18 Even so, Taylor regards the Saigon government as having a superior claim to represent “Vietnamese nationalism” in whatever form it may exist.

I discussed this issue in the preface to my book The Vietnamese War: Revolution and Social Change in the Mekong Delta, 1930-1975.” Among other things I noted that David Marr, the scholar who became most prominently identified with the proposition that the Ho Chi Minh followers had a monopoly on Vietnamese nationalism, actually had a far more nuanced view, which he advanced at the very height of the passionate polemics about the Vietnam War.

“David Marr’s extensive writings on Vietnamese modern history have amply documented the deep nationalist roots of the Vietnamese revolution, but he was also one of the first of the ‘wartime’ scholars to challenge the view that the Vietnamese Communist Party had a monopoly on Vietnamese nationalism or that there was a single Vietnamese ur-nationalism which had been passed down unchanged across generations. While the war still raged in 1971, he wrote ‘to date, in the West, the focus has been almost entirely on the Indochinese Communist party, the Viet-Minh, and the National liberation Front… In part this is because the study of Vietnamese anticolonial movements has been largely the preserve of the political scientist, the practicing journalist, and the intelligence specialist.’ Nevertheless, Marr’s conclusion was that ‘By 1945 salvation from the foreigner was taken by the peasantry to include salvation from hunger, tenantry, and taxes – a merging of activist and reformist ambitions that continues to motivate many in the conflict now under way,’ clearly implying that the diverse strands of early modern nationalism had been fused by the revolutionary movement.”19 Taylor goes well beyond this in asserting that “A ‘common history’ lies in the realm of mythology and indoctrination.”20

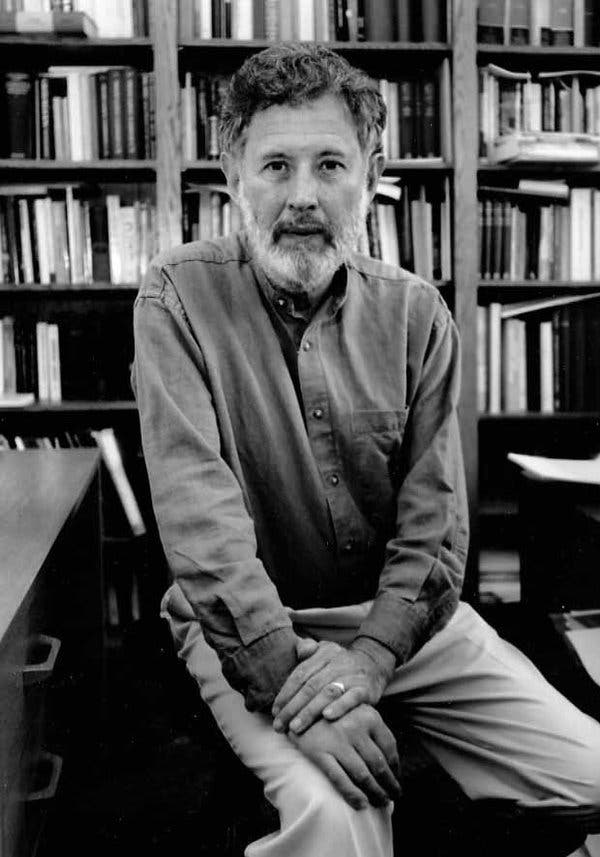

David Marr came to Cornell during my second year of graduate studies in 1969, and taught there for several years as a Visiting Assistant Professor. The intellectual stimulation he provided in his courses and individual tutoring also provided the deeper academic grounding in modern Vietnamese history that I had been seeking. During my year at Monterey we were never exposed to this kind of background, indeed I think the Vietnamese program deliberately avoided discussion of recent Vietnamese history because it would raise issues which might be problematic. To the extent that we learned anything about modern Vietnam it was largely confined to the summary of the one-paragraph version that was presented in Saigon text books: “In 1945 the entire people rose up against the French colonialists. In 1954, the communists deceitfully colluded with the French to divide the country.” Nothing further was said about how this came to pass, and the subject of how the insurgency started was avoided altogether. While in Vietnam, in the Army and RAND, I was so busy with the immediate day to day press of business that I did not have time to read broadly on the subject of Vietnamese history. While I learned a great deal about the international and regional dimensions of the conflict from David Mozingo and George Kahin, it was David Marr who provided the entrée into the complexities of modern Vietnamese history.21

David Marr

The Cornell Mafia

Every teacher is aware that much, if not most, of the “learning” that takes place in graduate school comes from contact with fellow graduate students. Ben Anderson has written about the great diversity of graduate students studying Southeast Asia at Cornell. “I think it was partly this amazing jumble of students in constant everyday contact with one another, that built strong bonds of solidarity that lived on long after the youngsters graduated. [In his autobiography Ben took to calling his grad students of the 1960s “youngsters” though many were nearly the same age -I was a year younger- and some of my grad student contemporaries were older than

Ben]. This is why the legend of the ‘Cornell Mafia’ still survives today, and why Cornell was so unusual compared to most other, later centres for Southeast Asian studies where American students were usually in the great majority.”22

I was extremely fortunate to be part of a remarkable cohort of graduate students, especially the political science students with Southeast Asian interests. One of the reasons I was an attractive candidate for grad school in the eyes of the Cornell administrators was that, having completed my military service, I could not be drafted out of school.23 It was not accidental that in my 1968 intake of Government Department graduate students, there were only a handful of males who might have been vulnerable to the draft. Two of my 1968 Government Department cohort were State Department officers who did not stay on for a degree, another was the scion of a powerful Singapore family who did not have an academic career in mind. Still another was an amputee – though I am not sure he stayed for a degree. Thak Chaloemtiarana was a Thai, who received his Ph.d in 1974 and became a permanent fixture at what became the Kahin Center of Southeast Asian studies, and later the director of the program. There was also Gareth Porter and myself. Lee Poh-ping arrived at the government department in 1968, received his Ph.d in 1974 and returned to Malaysia to teach. Joel Rocamura from the Philippines, who was a rare example of a Southeast Asian studying a Southeast Asian country other than his own (Indonesia), had come to the government department in 1967, and later became a fixture at 102 West Ave.

Four of the “Cornell Mafia” at the memorial service for George Kahin in Ithaca in 2000. From left Thak Chaloemtiarana, Gareth Porter, Jayne Werner, and DE.

Of this cohort, as far as I know only Gary was draft-eligible, though he may have received a deferment of some kind. With the exception of the two State Department officers and Goh Kian-chee from Singapore, almost all the rest eventually obtained their Ph.d’s: Thak and Lee Poh-ping in 1974, Gary and I in 1976, and Barbara Harvey (1974).

DE and Barbara Harvey at George Kahin’s memorial observances in Ithaca, 2000.

Many of the women from my class and previous ones went on to distinguished academic careers, including Jayne Werner, who co-authored the monumental Sources of Vietnamese Tradition volumes, among her important works. But the person who made the earliest and strongest impact on me was Gary Porter, who went on to a productive but very controversial career outside academe.

Even in the most heated periods of campus turmoil centered on the Vietnam I was never an object of attack for my work on Vietnam with the Army and with Rand, indeed some of my closest friendships were with fellow grad students who were at the center of antiwar activism on campus. Most prominent among these was Gary Porter, who arrived at Cornell the same year that I did. One of my vivid early memories of the Cornell experience was descending down the long sloping hill from the upper campus to the ramshackle building at 102 West Avenue.

Along one of these paths I had a prolonged and intense argument with Gary Porter about immediate withdrawal from Vietnam in the Fall of 1968. It was the first time I had been forced to intellectually confront the stark implications of accepting that the Vietnam War was unwinnable.

I can’t remember the details of our conversation, but I do remember that it was a heated exchange. I stipulated early on that I had concluded that the Vietnam War was unwinnable, to which Gary’s immediate response was that I must then accept the logical corollary that America should immediately withdraw all of its forces and cut off aid to the South Vietnamese government in order to bring the pointless bloodshed to a close. For me that was a bridge too far.

I realized that whatever the United States did to prolong the war was only postponing the inevitable defeat of its ally and those who had opposed the communists and extending the bloodshed, but to me, the idea of abandoning those who I had worked with and had family ties to was abhorrent. It was one thing to abandon ship, but another thing entirely to sink the boat as we left by cutting off all aid. Intellectually, I realized that protracting the conflict would only be a temporary reprieve for them, and would only add to the growing list of victims of a pointless war, but I still could not bring myself to advocate cold-turkey abandonment of the South Vietnamese who we had instigated and abetted to join us in a venture that had little to do with their long term or short term interests. I hadn’t yet heard of the memo written by McNamara’s deputy John McNaughton in March 1965 which coldly rejected that idea that American policy toward Vietnam was significantly influenced by any intention to benefit our allies. (“. US aims: 70% –To avoid a humiliating US defeat (to our reputation as a guarantor). 20%–To keep SVN (and then adjacent) territory from Chinese hands.10%–To permit the people of SVN to enjoy a better, freer way of life. ALSO–To emerge from crisis without unacceptable taint from methods used. NOT–To “help a friend,” although it would be hard to stay in if asked out.”24 Still, I had seen enough to know that whatever qualms those of us with close personal ties to non-communists in South Vietnam, their ultimate fate and the costs they would bear for America’s actions and inactions were of little concern to American policy makers in Washington.

I wasn’t impressed by the abstract arguments about dominos and credibility, but I couldn’t bring myself to advocate compounding one human tragedy with yet another by an immediate and inevitably chaotic withdrawal. At that point I would have gladly accepted Kissinger’s “decent interval” strategy as a compromise between immediate withdrawal and senseless prolongation of the war. I was hoping for an improbable soft landing for the non-communist Vietnamese. Gary, however, was having none of it. Employing his trademark political passion and polemical skills, he relentless bored in on the logical flaws in my position (why prolong a war that you admit is lost on the grounds that it would lead to bad consequences for the non-communists who are already being chewed up by the conflict?).

Over the course of another six years at Cornell and two (1971-72) in Vietnam, I eventually came to accept the position that the war simply had to be ended, letting the chips fall where they may. But the fact that it took so long to arrive at this conclusion led me to avoid direct involvement in the anti-war movement at Cornell, even though I agreed with most of its analysis of the war and was on good personal terms with most of the activists in this movement. I did not join the Committee for Concerned Asian Scholars (CCAS) because I was determined to stay focused on the academic mission which had drawn me to Cornell in the first place, and because I did not feel comfortable endorsing the maximalist anti-war positions that CCAS tended to advocate. In addition, I was contemplating a return to Vietnam for research and did not want to burn any bridges which might prevent this.

In this regard, I felt closer to my fellow grad student Christian Hauswedell, a German who was, like me a government department student who worked closely with David Mozingo. His specialty was Indonesia and China in the international relations of Southeast Asian. As a European, Christian naturally opposed American policy in Vietnam, but also did not feel a political responsibility for it. His critique of the war was that of a detached observer rather than a passionate partisan. I developed a close relationship with Christian over the course of my years at Cornell.

Members of the working class. DE blasts out a driveway for his car at 220 Giles St. Ithaca, as Christian Hauswedell looks on.

I was not the only graduate student in the government department with real world experience. My paltry seven years in Vietnam, most of it behind a desk, paled in comparison with the extraordinary career of Stan Bedlington, who had arrived at Cornell the year before I did. Stan was born in Britain, and commenced his mandatory national service in 1946 at age 18 in Palestine during the turbulent British withdrawal. While there he became fluent in Arabic. On the strength of his demonstrated capacity for languages he was asked to go to Malaya, where he learned Cantonese with near native fluency. During the Emergency Stan did hands-on counterinsurgency. “He arrived in Malaya in 1948 and was assigned to Kelantan, a state in the far northeastern part of the colony. He participated in para-military jungle squads, waiting in ambush positions for days covered in leeches to attack small companies of Malayan Communist Party soldiers (known as “Communist Terrorists” or “CTs”).”25 After completing his undergraduate studies at Berkeley in the early 1960s, where he was inevitably radicalized, he decided to pursue graduate studies at Cornell’s government department and Southeast Asia Program and arrived there in 1967, a year before I did. Stan was very understated and British, but nevertheless quietly active in CCAS and other campus activities.

One memorable incident that taught me everything I needed to know about why Stan opted to live in the United States, was a social event where both Stan, who came from a modest background in County Durham, and the insufferable Simon Head [soon to be “Lord Simon”] who spent a short time at Cornell’s Southeast Asia Program, were present. “Well, now, Stanny-Wanny,” said “Lord Simon” to Stan, voice dripping with supercilious condescension and affirmation of caste-superiority. Among the many items that turned me into an Anglophobe, this stands out. Failing to get a permanent teaching job after he received his Ph.d., Stan eventually went to work for the CIA and became one of their leading counter terrorism specialists, reaching the top of his profession despite his complicated past. Only in America.

Stan Bedlington (left). DE and Stan Bedlington at George Kahin’s memorial observances in Ithaca, 2000.

102 West Avenue: Nerve Center of Cornell’s Southeast Program

As Gary Porter and I continued our argument about Vietnam withdrawal we were probably on our way to attend one of the regular brown bag lunches featuring various speakers on topics relating to Southeast Asia, which brought a number of informative experts to the campus and was a center for intellectual interchange between faculty and students in the SEAP. The building at 102 West Avenue also provided a few offices for advanced graduate students in the SEAP who were in advanced stages of their dissertations (I had an office there in 1973-76).

102 West Avenue in 1989 prior to its demolition.

102 West Avenue was the magnetic center around which the intellectual and social life of most in the SEAP revolved. It was a former fraternity house which had gradually been occupied by the SEAP which eventually became its sole occupant. In his humorous account of the evolution of 102 West Ave., George Kahin notes that this ramshackle building was only saved from early demolition by the fortuitous appearance of Dan Lev as a graduate student in Indonesian Studies. (Indeed the SEAP during the 1950s and early 1960s was totally dominated by the Modern Indonesia Program, which Kahin also ran. It was only in the mid 1960s that Vietnam became a focus of comparable importance).

Kahin’s history of the Modern Indonesia Program has a section on 102 West Avenue. “Had it not been for the fact that over the decades of CMIP’s occupancy of the building the morale and cooperative spirit of the scholars who worked there remained so strong, the building would not have lasted until today [written in 1989 as the building was about to be demolished]. But clearly the periodic gotong royong (mutual help) exercises in which all occupants pitched in together, to paint, make minor repairs, etc., prolonged its life. Also important in extending the building’s life was the imagination and unusual engineering prowess of one of the early CMIP fellowship holders, Daniel S. Lev, the only member of the Project to have held a carpenter’s license. (Also known for other accomplishments, he is now professor of political science at the University of Washington.) Indeed, without his input the building might well have much earlier been condemned as office space (as well as for living quarters), for by 1962 the rapid sagging of the first floor into the basement seemed to portend the whole building’s imminent collapse. Returning in that year from field research in Indonesia, Dan promptly took measure of this depressing situation— and perhaps of his prospects for long having a room in which to write up his dissertation! Requesting only $50 from the Project’s emergency fund, he returned from an Ithaca construction firm with two second-hand adjustable six-foot steel jack posts. These he inserted at just the correct points and cranked them up a good foot under the beams that were then hesitatingly holding up the first floor. Except for a few areas of only six to eight inches of sagging the building has stood— however precariously— ever since. Perhaps this is also because a contemporary of Dan’s provided the old building with a sort of spiritual nourishment that may well have given it the continued will to live. Ruth T. McVey (recently retired as Reader in Southeast Asian Politics at London University School of Oriental and African Studies) gave it the supreme accolade by dedicating to it her classic study, The Rise of Indonesian Communism.”26

Kahin observed that “It is here, I think, appropriate to note that, the well known pundit on administrative organization, C. Northcote Parkinson (also a scholar of Malay history) visited Cornell and CMIP’s building at 102 West Avenue shortly before he completed writing his book, Parkinson’s Law. It will be recalled that one of his several laws, had to do with buildings, and held that the value and quality of the work undertaken inside them is exactly in reverse relationship to the quality of the premises in which the work takes place. We always liked to believe that in arriving at this insight Professor Parkinson had been inspired by his visit to 102 West Ave. Belief in this maxim undoubtedly helped raise the morale of some of the struggling scholars who over the years have worked there, and, as with Ruth McVey’s dedication, may have contributed to that venerable building’s will to survive.”27

Indeed, Ruth McVey, who was not at Cornell during my time there, is a good illustration of the continuity of intellectual influences engendered by the SEAP. She had been a forceful presence during her time there in the early and mid-1960s, and had coauthored the famous “Cornell Paper” which attempted to debunk the Suharto version of the 1965 coup in Indonesia. Both George Kahin and Ben Anderson often referred to her, and her critique of the “domino theory” lived on at Cornell through them and lives on today in the writings of experts like Cornell’s Southeast Asian authority in the Government Department, Tom Pepinksy.28

102 West Avenue was not the only off-campus enclave of student-faculty interaction. We have already noted the role that the Telluride House played.29 Soon Martin Bernal, a British China expert who David Mozingo invited to come to Cornell took up residence there. Bernal later wrote that when he accepted Cornell’s offer “I asked my patron, David Mozingo, whether there was such a thing at Cornell as a ‘respectable commune’. A few weeks later, I received an invitation from an institution called Telluride House. As I understood it, it was an intellectual fraternity run by the students who lived there. As a faculty member I would have free board and lodging and no supervisory responsibilities. It was exactly what I wanted, and I wrote David to thank him. He responded that it had not been his idea and that he would never have recommended me to that ‘nest of right-wing vipers’. It turned out that I had been recommended to Telluride by a right-wing colleague, Werner Dannhauser, a close friend of Allan Bloom and an ardent Straussian. I was startled but went ahead. I remain puzzled that he should have proposed me. My only explanation is that he thought ‘better Red than social scientist.’!”

By the time Bernal arrived at Cornell and Telluride, the intellectual and political environment at Cornell had considerably shifted from the 1968-69 period. “When I arrived in 1972, the biggest reform had just taken place, the admission of women. Nonetheless, the house still had a masculine atmosphere. With the ameliorating presence of women and without the time-consuming activities of prayer and penance, the house was like a lax monastery, an ideal place to live. … My sponsor David had been right to describe Telluride as a ‘nest of right-wing vipers’. In the long run of more than forty years, I think I can see a pattern. The house goes in the opposite direction from Cornell as a whole. When the predominant political culture is left wing or liberal, and when the university is to the left, the house veers to the right. When I arrived in 1972, the right wing glory days, when the house was successively dominated by Allan Bloom and Werner Dannhauser, were over, but many of their students were still central to the institution.” To his disappointment, Bernal found that the Straussians like Francis Fukuyama, ‘only wanted to talk about Plato.” “I had come to the United States assuming that I could escape the stultifying Eurocentrism of Cambridge, only to find, at least as far as Telluride was concerned, it was out of the frying pan into the fire.”30

Martin Bernal

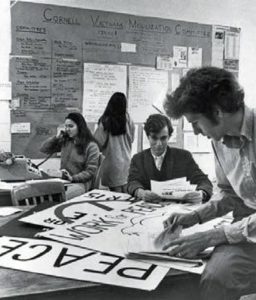

CCAS – The Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars

The radicalization of scholars at Cornell was part of a national trend, that was formally inaugurated by the formation of a national group comprised mainly of graduate students styling itself the Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars. Mark Seldon, one of the founding members of CCAS described its origins in the following terms: “As the statement of purpose indicates, CCAS was born of the Vietnam War and the antiwar movement of the 1960s and 1970s and, Fabio Lanza’s opinion notwithstanding [Lanza argued that the early founders of CCAS were pro-Maoist student radicals primarily interested in China], its primary focus until 1975 was the Indochina Wars and American imperialism in the Asia-Pacific. This was despite the fact that there were few Indochina specialists in our ranks and the largest numbers of our members were China researchers, some of whom were also deeply involved in charting the opening of U.S.–China relations.”31

CCAS was critical of established scholars and institutions in Asian Studies, especially the Association for Asian Studies which was the academic organization that represented the community of scholars specializing on Asia. The Social Science Research Council, which was the umbrella group for allocating grants funded by various foundations for social science research, also came under attack. Selden writes that these critics “pointed to the Ford Foundation’s major funding of contemporary China Studies as pivotal in consolidating the research agenda and inaugurated a boycott of SSRC, demanding the release of documentation on the group’s decisions shaping the field. Regrettably, no Edward Snowden appeared to open the books, but the boycott raised tempers in some quarters and led many researchers of the era to think hard about the sources of funding that had underwritten the field’s rapid growth in these years. Indeed, researchers of that generation confronted the dilemma of whether to accept funding provided by the U.S. Department of Defense or the Ford Foundation, the very institutions that some criticized.”32 John Fairbank, the eminent Harvard professor who was a critic of official China policy came under attack for accepting what some CCAS purists felt was tainted money from the Ford Foundation and other establishment groups, as did George Kahin, despite his eminence as an antiwar figure. Many of Kahin’s grad students (including me) benefitted greatly from Ford’s largess. In addition, the CCAS tendency to equate SSRC and foundation funds with all other sources of government funding paradoxically reduced the sensitivity of my using Rand and ARPA funds for my return to Vietnam, since it was regarded as essentially the same as SSRC and Ford money. The radicals, as they often did, targeted institutions which they felt would be more vulnerable to their pressure and moral censure, and assumed that only revolution would cut off government funding for what they considered counter-revolutionary projects. The more innocuous the target the closer it was likely to be to the reach of the activists, who would inevitably pursue the low-hanging fruit.

CCAS had been formed at the annual meeting of the Association of Asian Studies in Philadelphia in 1968, but its maiden voyage as a political action group came in 1969, at the AAS meeting in Boston, which I attended. I had been invited to attend a panel sponsored by the Southeast Asia Development Advisory Group (SEADAG), which had been set up by establishment academic specialists on Southeast Asia and supported with funds provided by the Agency for International Development (AID). This was precisely the type of government infiltration into academic research that CCAS had been formed to protest.

Although Cornell was well represented by grad students in Boston, CCAS at Cornell was in its infancy and the activists in Boston were largely from nearby Harvard. The Harvard Crimson reported that “This year CCAS held its own national conference at the time of the AAS meeting (March 28 to March 30), in a nearby Boston hotel. Its purpose was two-fold: to re-evaluate America’s role in Asia and the scholarship which has justified it, and to consolidate CCAS as an organization to further these goals.”33

“One of the original concerns of the CCAS organizers was the ‘irrelevance’ of AAS panel topics–the Vietnam War and Communist China, for example, were conspicuously absent on the AAS program. In contrast, the two or three hundred people who attended the CCAS conference discussed such topics as ‘People’s War and the Transformation of Peasant Societies,’ ‘The Limits of Liberal Asian Scholarship,’ and ‘Social Sciences and the Third World.’ Boston University professor Howard Zinn told the audience at an AAS discussion, ‘When I compare the CCAS program with the AAS program, I applaud.’”34