5

While most of America and people at Cornell were consumed with finding a way out of Vietnam, I was equally engrossed with finding a way back in. I had a sense that I would be a witness to the final chapter of the conflict and wanted to be there to document what I felt was certain to be a controversial and pivotal moment in the history of both America and Vietnam. The immediate origins of the conflict in the late 1950s had not been well documented by eyewitness accounts. The overwhelming bulk of the documentation about the war had been done during the height of the American intervention, when Rand and other researchers flooded the country. Now that the war was winding down, so, too, was the American interest in it. I thought the tragedy of our ignorance in intervening in Vietnam would be compounded if we were equally clueless about the way it ended, and the reasons for the failure. Sadly this turned out to be the case, as many Americans (and Vietnamese) concluded that the collapse of the South Vietnamese regime was due to North Vietnamese tanks crashing through the gates of the Presidential palace, without much attention to how and why the situation had changed between 1971 when the GVN seemed on the brink of victory, and April 30, 1975 when it collapsed in shambles. My research did, at least, show that the “brink of victory” view was illusory.

In addition, I had planned to base a significant part of the research for my thesis about the establishment of the institutions of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam after the Geneva Agreements on interview accounts of those who had lived and worked in that system. The only source available was North Vietnamese prisoners and defectors who were in South Vietnam. I had hoped to reestablish my former contacts from the first Rand project in My Tho to do an update of the 1965-68 study, and then use these same contacts to gain access to North Vietnamese prisoners and defectors for my dissertation research.

Although Gerry Hickey and other anthropologists were encountering problems about the conditions under which their research was undertaken, the even more troubling issues of human subjects of interviews in wartime situations was only beginning to appear on the horizon. For me, having already done the earlier Rand study, I was convinced that the historical value of the eyewitness accounts to an important cold war issue would be sufficient justification for the project. I was well aware from my Cornell experience of the potential controversy, but my personal drive to understand the complexities of Vietnam swept aside any scruples I might have had. David Mozingo was supportive, and so, reluctantly, was George Kahin, who clearly had reservations about my dissertation plan, but did not try to deflect me. Kahin was probably intrigued by the possibility of producing a counter-narrative to the Washington view of North Vietnam from authoritative insider accounts of how the system operated.

A major obstacle to this plan was finding a willing sponsor. Fred Iklé , chairman of the Social Science Department at Rand had told me in June 1969 that Rand had no interest in such a study, since it too had no interested government sponsor to pick up the tab. It was clear that the controversies generated by earlier Rand studies and the collapse of interest in pacification or any other aspects of the military side of the war after the Tet Offensive made a “Dinh Tuong II” project a non-starter for Rand. But a number of factors that emerged in the post-Tet period gradually brought new elements into the situation.

The first was that, contrary to many people’s expectations, newly elected President Richard Nixon decided against a rapid termination of the war, which meant that it would endure as priority issue throughout his first term in office. In addition, starting in 1969, reports of progress in pacification began to reach Washington, after a year of post-Tet gloom and doom.

As I wrote in The Vietnamese War: “The Washington Post reported right after President Richard Nixon’s inauguration that a comprehensive policy review of Vietnam policy elicited ‘galloping optimism’ among American officials in Vietnam, despite the skeptical tone of the questions posed in Washington.” The answers to questions about how the war was going “for the most part reflected the dominant theme of high American officials in South Vietnam that the war, to quote one official, ‘is going better than at any time since 1961.’ ” The optimism reflected a view that “it is not so much a question of allies doing better as the enemy doing much, much worse, and the population becoming increasingly disenchanted with the war.”1

The following year, in October 1970 the New York Times reported that “opinion in US has been polarized for so long that it has not kept up with realities of Vietnam and is about [two years] behind current events.” U.S. officials maintained that the “allies have never been stronger and [the] enemy never weaker,” though there was still uncertainty about how the South Vietnamese would perform on their own. Because of the legacy of previous overconfidence and the resulting credibility gap between official pronouncements and the U.S. public, “officials are reluctant to express their new optimism openly…”2

From the early Nixon administration on, many insiders were skeptical of the “New Optimism,” as the Washington Post reported in February, 1969. “a reluctance on the part of NSC [National Security Council] staffers to ‘believe the good news.’”3 From my perspective, this was a ideal constellation of opinions about the war. The “new optimism” put Vietnam back on the policy agenda, while the skepticism of some NSC staffers created an incentive to gain a more accurate and realistic understanding of what was really happening in Vietnam.

Among the NSC skeptics was Bob Sansom, who had been very supportive of my earlier work in Dinh Tuong, which he found very helpful for his own research. Sansom had become the National Security Council staff member in charge of collating and analyzing information on the Vietnam War in the Vietnam Studies Group of the NSC, and had a strong interest in being well informed. The idea of having an independent source of information about the situation in the Mekong Delta therefore appealed to him. In addition, his own research in Dinh Tuong gave him a personal interest in the area. It was, therefore, Robert Sansom who generated the momentum for my return to Vietnam.

February 17, 1970. President Nixon signing Foreign Affairs Message as Henry Kissinger and members of the National Security Council (NSC) stand nearby. Photo Oliver Atkins – courtesy Nixon Library

Bob Sansom is third from the right, one over from General Alexander Haig, who is (appropriately) on the far right. Tony Lake who would shortly resign from the NSC in protest against the Cambodian invasion is sixth from the right, and behind Kissinger.

I had been in touch with Bob Sansom since he assumed his position on the NSC, and Sansom evidently made his support of a My Tho project known to Rand. On April 5, 1970 I sent two proposals to Fred Iklé, one outlining a continuation of the My Tho project, and the other a series of interviews with North Vietnamese prisoners and defectors. Despite his emphatic rejection of any further interview projects in Vietnam the previous year, Iklé now responded positively. He wrote that “Both are of great interest and could turn into excellent projects,” and added, “We are right now trying to line up support . . .and will be in touch with you shortly. I am fairly confident that one of these studies, if not both, can be undertaken more or less along the lines you propose.”4

It was certainly Sansom who provided the momentum for this sudden revival of Rand’s interest in my resuming research, since Rand was always on the lookout for ways of remaining on the radar of Henry Kissinger and the NSC. Sansom responded on July 9, 1970, that the proposal looked “superb” and that he could not add anything to it.5 At that point, it looked like my return to Vietnam was a done deal.

I had one interested supporter in Rand, “Blowtorch Bob” Komer,6 who had left his position as pacification czar in Vietnam (head of the Civilian Office of Revolutionary Development or CORDS) in the waning days of the Johnson Administration, and had ended up with Rand, writing up his Vietnam experiences.

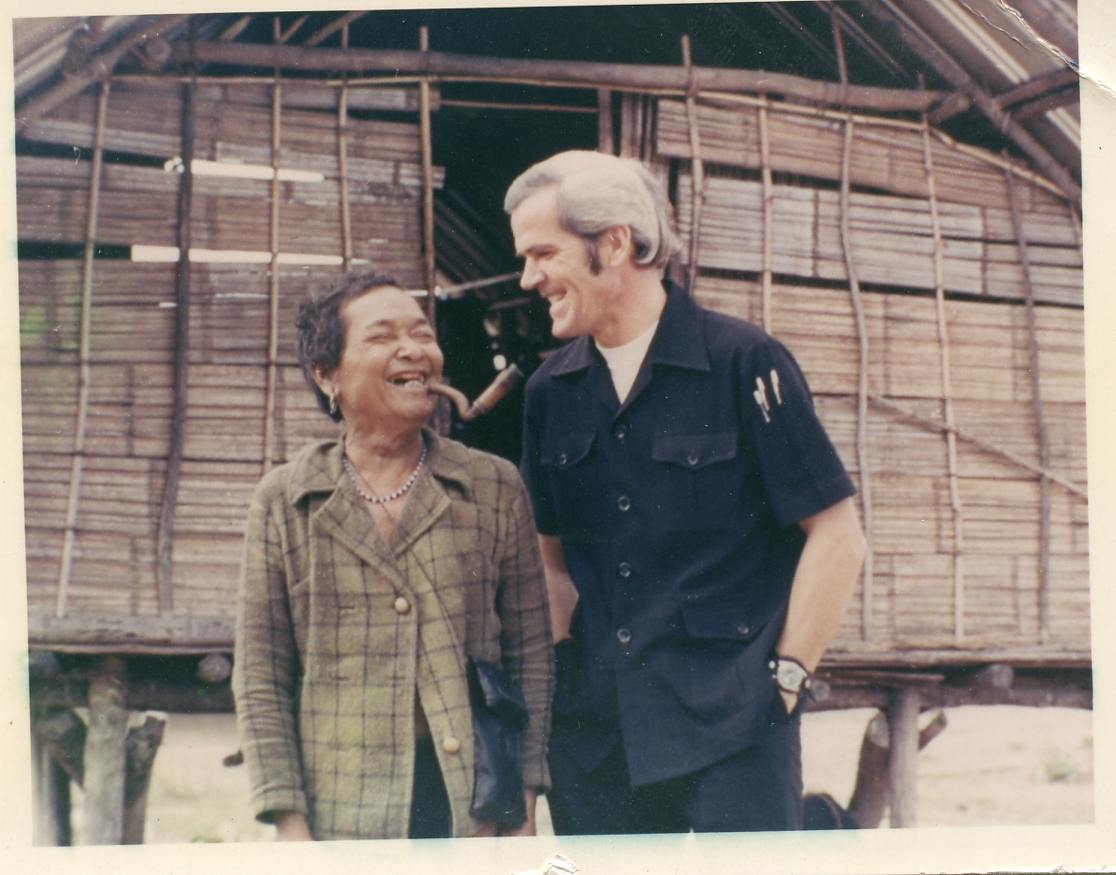

“Blowtorch” Bob Komer – onetime “pacification czar’ in Vietnam

On a trip I took to Santa Monica sometime in the fall of 1970, when it looked as though my departure for Vietnam was imminent, Komer offered some encouragement, and noted that the new province chief of Dinh Tuong was the dynamic Col. Le Minh Dao, who later distinguished himself by his heroism in the last stand of ARVN forces against the North Vietnamese making their final assault on Saigon in 1975. With his usual bluster, Komer said, “Tell Col. Dao you’re one of my boys.”

Le Minh Dao after promotion to brigadier general Col Le Minh Dao

I didn’t find the role of acolyte in the Bob Komer club especially appealing and, needless to say, did not bring up Komer when I finally met Col. Dao. But, as it turned out, Bob Komer was the only one at Rand or in government who paid attention to my reporting once I was on the ground and was consistently supportive of my work. I suppose I should have been grateful.

However, months passed without any finalization of the project. I waited in limbo in Ithaca without any clear idea of what the holdup was. Finally, in December 1970, I received a letter from Rand that explained that the military had rejected the idea and that the MACV was denying the “theater clearance” necessary to enter Vietnam in an official capacity. Without this validation of credentials by the American Government, the Vietnamese government would not issue me a visa to enter the country for purposes of research. This was a major setback, since I did not have a “plan B” in the event the Vietnam project fell through.

The prime source of opposition evidently came from General Creighton Abram’s headquarters, the Military Assistance Command-Vietnam (MACV), which asserted that it was fully on top of the situation in Vietnam, which it claimed was going well. MACV, therefore, did not require or welcome any competing assessments. Moreover, MACV said that supporting such a project would be an unacceptable burden on its limited (and diminishing) resources. (In the event, other than supplying some office space for Mai and providing APO privileges, MACV did nothing at all to facilitate or support the project when it finally got underway). MACV’s objections were outlined in a December, 1970 telegram informing Rand that the proposal to do interview research in My Tho had been rejected.7 I later saw the pile of correspondence relating to this project, which was an inch thick.

I had not corresponded with Bob Sansom during this period, and so did not know the inside story of the controversy stirred up by my proposed return to Vietnam. It was clearly Sansom who broke the impasse by using his position on the NSC to urge the intercession of his NSC boss. The Rand Study on its various Vietnam projects notes “The logjam was finally broken when General Alexander Haig delivered a message from the National Security Council to MACV, asking that the project be approved. A memo later found in the National Archives indicated it was it was Sansom’s boss, Wayne Smith—Larry Lynn’s replacement on the National Security Council after Lynn resigned over the Cambodia invasion in 1970—who had intervened to get the project going by asking Haig on one of his trips to Vietnam to carry his message to Saigon.

“The memo to Haig, dated December 11, 1970, carried a notation in bold letters, “Urgent Action for Your Trip,” and addressed the subject of “David Elliott’s Study of the Viet Cong in Dinh Tuong.” Smith mentioned that Elliott had produced “some of this government’s best analytical work on the Viet Cong in his RAND studies of 1965–67.” Smith added that Elliott had “proposed to update his earlier work” and that the Vietnam Special Studies Group had “strongly urged him to do so.” Smith emphasized that Elliott’s study would be “an important contribution to our current knowledge on VCI [Viet Cong Infrastructure] strength and activities” and concluded by asking Haig to raise the issue with General Abrams, stressing that, “If we don’t get this turned around ASAP, we will lose Elliott and the study.” Smith pointed out that DoD supported the study, but MACV had just “turned down the proposal after dragging out their review for months (in the hope, undoubtedly, that Elliott would give up),” without giving any reasons for their rejection. The refusal “was signed by Chief of Staff Dolvin.” However, at Wayne Smith’s behest, Haig delivered a countermanding order to a MACV representative meeting him on the tarmac of Tan Son Nhat airport as he stepped off the plane, and the My Tho project received a green light.8

A Changed Landscape

When I last saw Vietnam in May 1968 just after the devastating second wave of the Tet Offensive, large parts of Saigon were in ruins, and consternation dominated both American and Saigon officialdom and many in Vietnam and America thought the war had been lost.

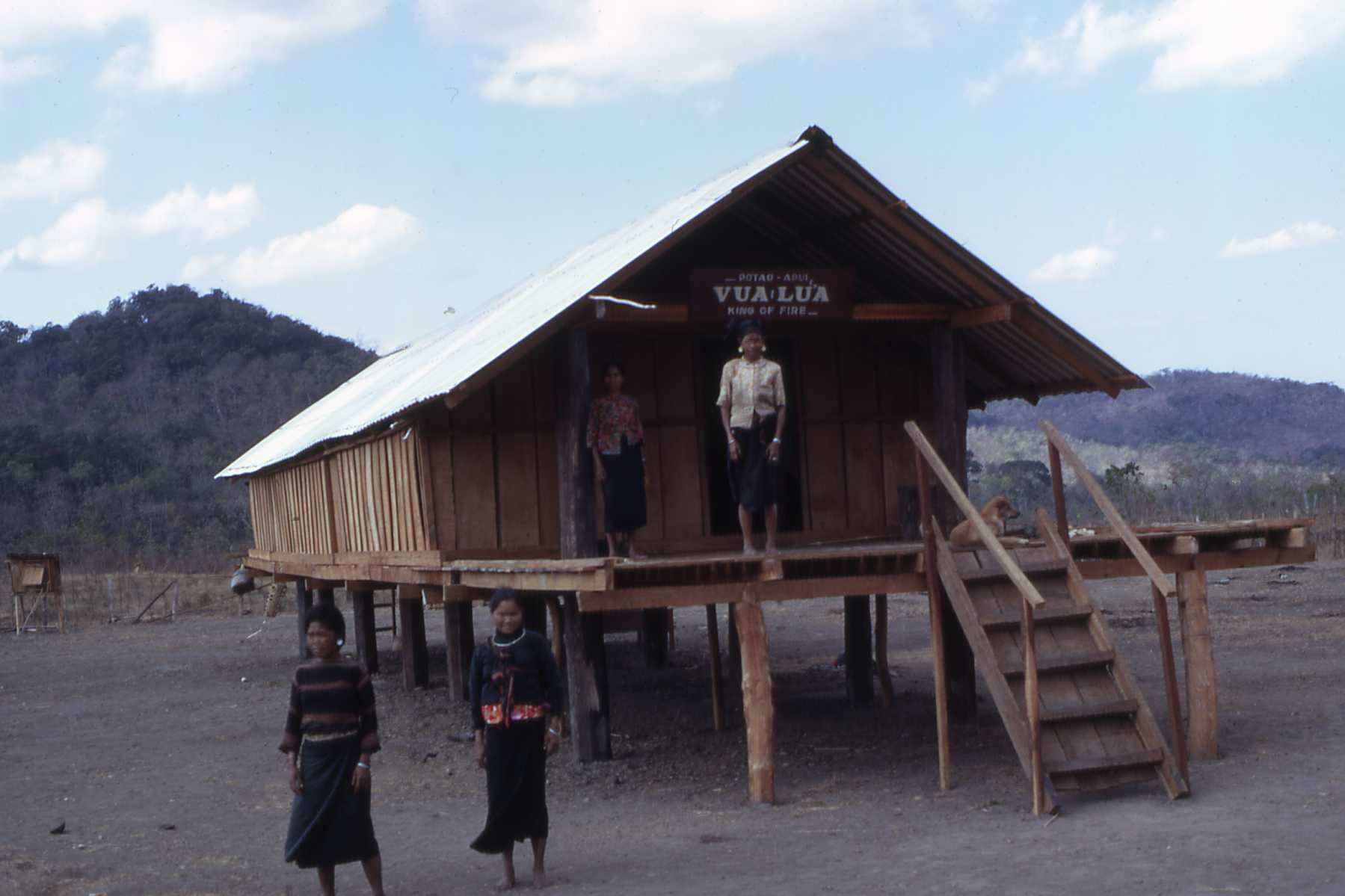

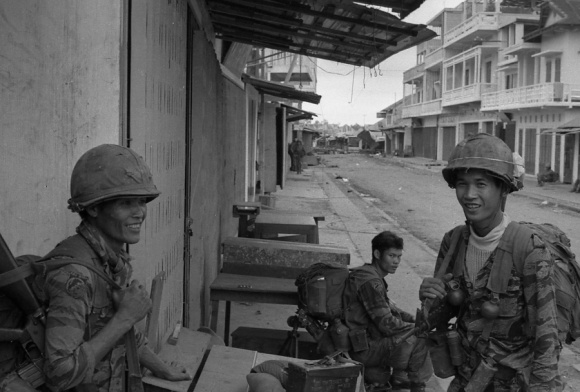

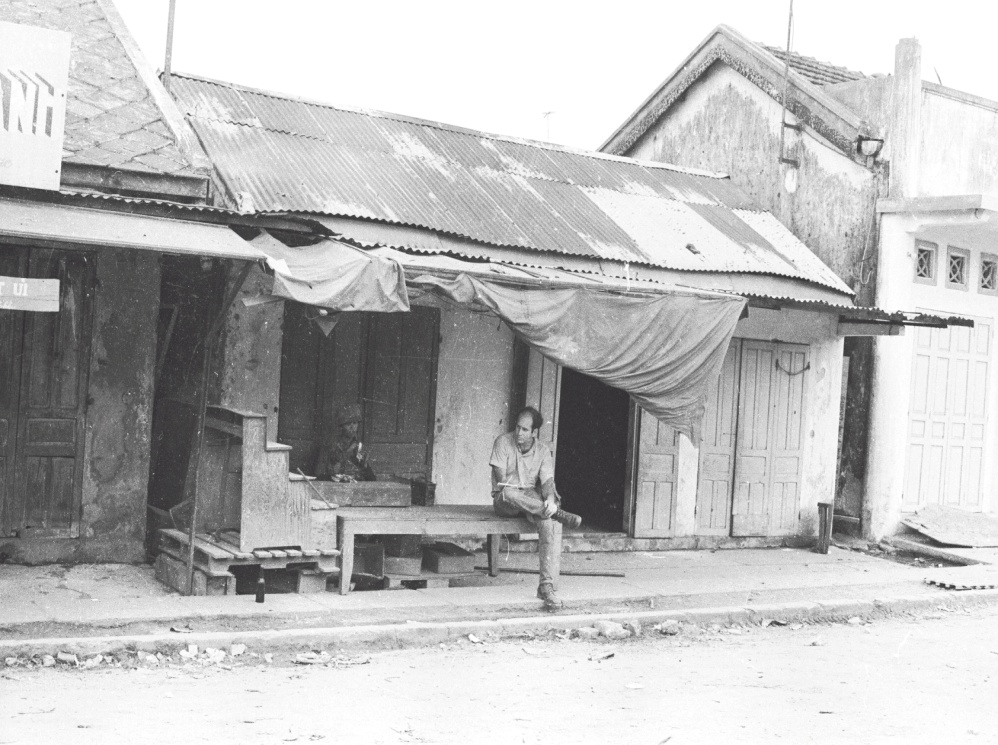

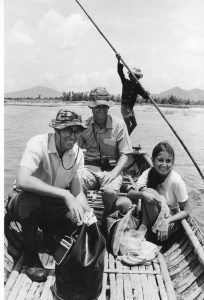

A section of Cholon reduced to rubble during the mini-Tet Offensive in April 1968

During my absence in the intervening period, I had been unable to follow the course of the war in any detail, and was dependent on news coverage which gave only a superficial overview of how the war was progressing. I had been reluctant to credit the “new optimism,” having encountered similar claims in the past. But, on arrival in 1971, we quickly found out that the security situation was indeed dramatically different from the chaos of 1968. The Viet Cong had been substantially weakened in many rural areas and it appeared as though vast swaths of territory had been “pacified” in the sense that one could travel widely in places like the Mekong Delta without fear of being shot at. There were a number of Americans in Vietnam who thought that the war was nearly over.

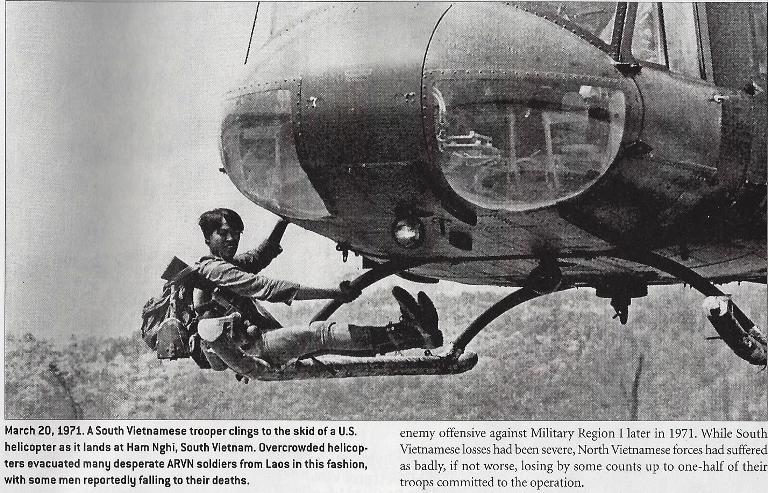

We arrived in Vietnam in February 1971. The following month, the GVN launched the disastrous Lam Son 719 operation against North Vietnamese forces in lower Laos. This was, in effect, a test of Vietnamization. The operation was largely planned by the ARVN (Armed Forces of the Republic of Vietnam) and American ground forces were forbidden to accompany the Saigon forces into Laos. The attack culminated in chaos and retreat, with memorable photos of panicked ARVN soldiers clinging to the skids of helicopters in a chaotic retreat.

On April 7, 1971 Nixon proclaimed that “Vietnamization has succeeded” – but this was a hollow boast that was clearly contradicted by the visual evidence of failure. This was the beginning of the end of the “New Optimism” but it did not receive a body blow until the Easter Offensive of the following year.

We embarked on the My Tho project at this critical juncture, where optimism reigned but clouds were appearing on the horizon. I can no longer remember the interactions I had with MACV and the US military in the weeks after our arrival.Apart from establishing APO mailing connections, MACV did nothing to facilitate the project. Somewhere along the line, MACV assigned a Major Smith as a liaison with ARPA, but any communications with him were left to my intiative. As far as I can remember, I never met Major Smith or discussed the My Tho project with him. In February 1972, I sent him a summary of our preliminary findings.

When Rand closed down the motivation and morale project in 1969, the spacious villa at 176 Pasteur was returned to MACV, which now used it as headquarters for a demolition unit. When we arrived Mai found a place to work at the ARPA compound.

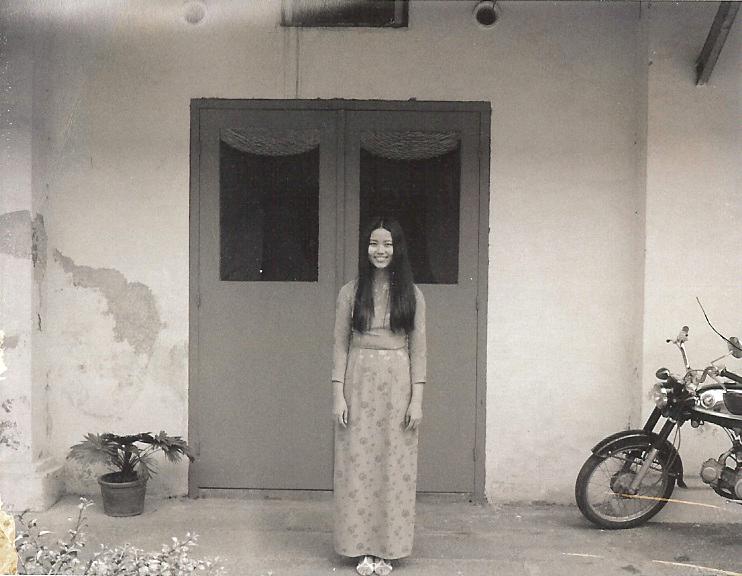

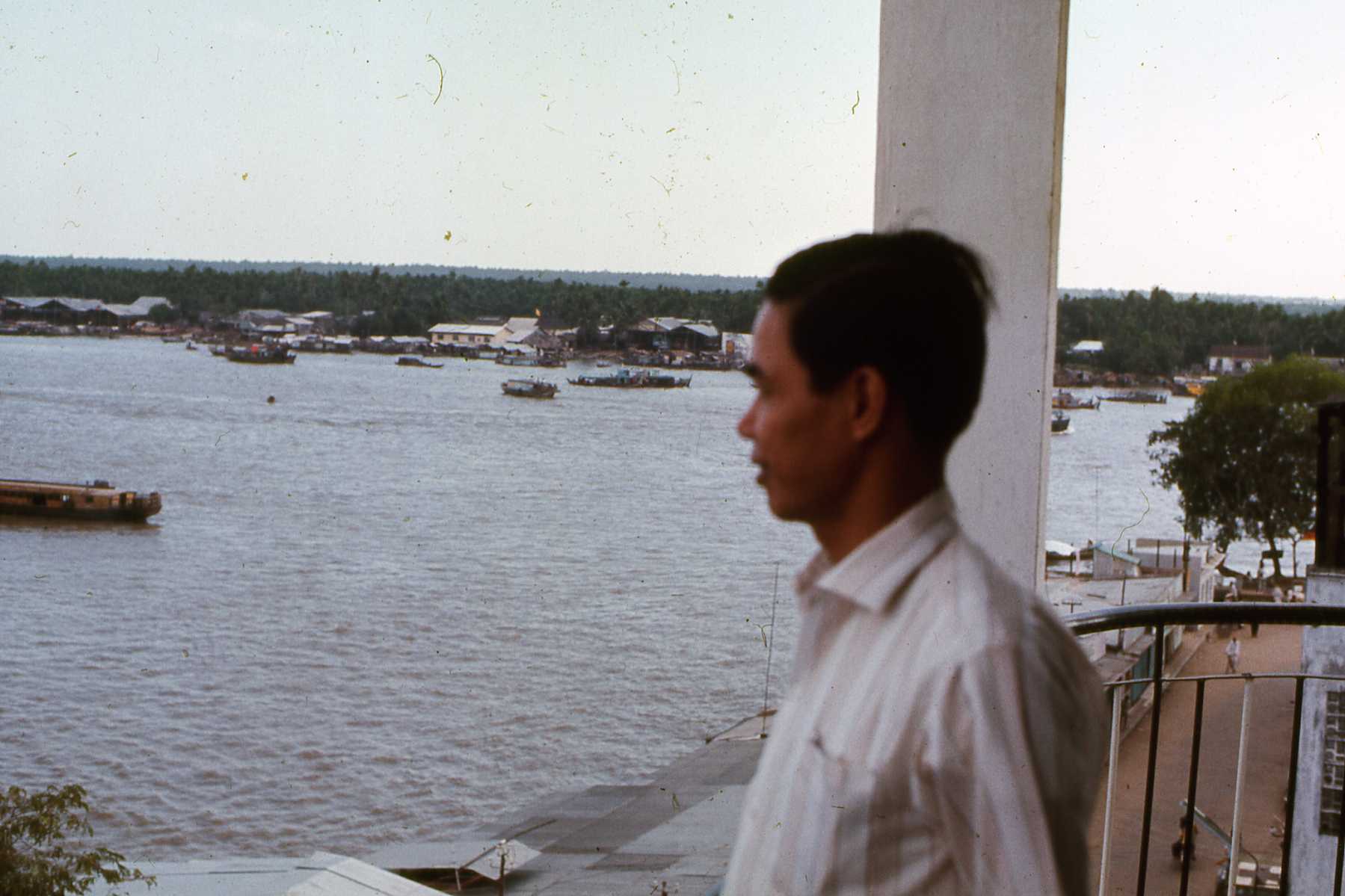

Mai in front of entrance to Rand office in ARPA compound 1971 Former ARPA compound on Ben Bach Dang, since demolished, now the Ton Duc Thang Museum 2019

DE, Joan Allen and Joe Carrier at Elliott Virginia farm, 1974

Gerry Hickey was still engaged in research, and working out of his apartment, picking up his mail at the ARPA compound along the Saigon river. Joan Allen was the administrative assistant supporting the modest Rand activities there. She remembered that there was “a sense of suspended animation,” in sharp contrast to the once bustling grand villa at 176 Pasteur.9 Other than that, the only Rand presence was Andy Sweetland of the Economics Department who had been sent to Saigon in 1968 as a caretaker for the interview programs which were being terminated. Sweetland moved to the ARPA office when Pasteur closed down, and made himself useful to MACV over the next several years using his computer skills to analyze data from the Hamlet Evaluation Surveys which attempted to measure the extent of Saigon’s territorial control of the countryside. When we arrived in early 1971, Sweetland was engaged in attempting to fine tune yet another version of the HES survey, which had by this time become so convoluted and immersed in figures that purported to measure economic development that it no longer accurately measured the simple indicator of how likely it was that the authorities would be shot at in a given place. As we were to discover, there were plenty of other fundamental problems with the HES, which we discovered during the course of our study. Joan Allen was Rand’s administrative assistant, based in the ARPA compound, supporting Hickey and Sweetland. Not long after our arrival, Joan left Vietnam and Mai assumed many of her duties, in addition to helping with the My Tho project.

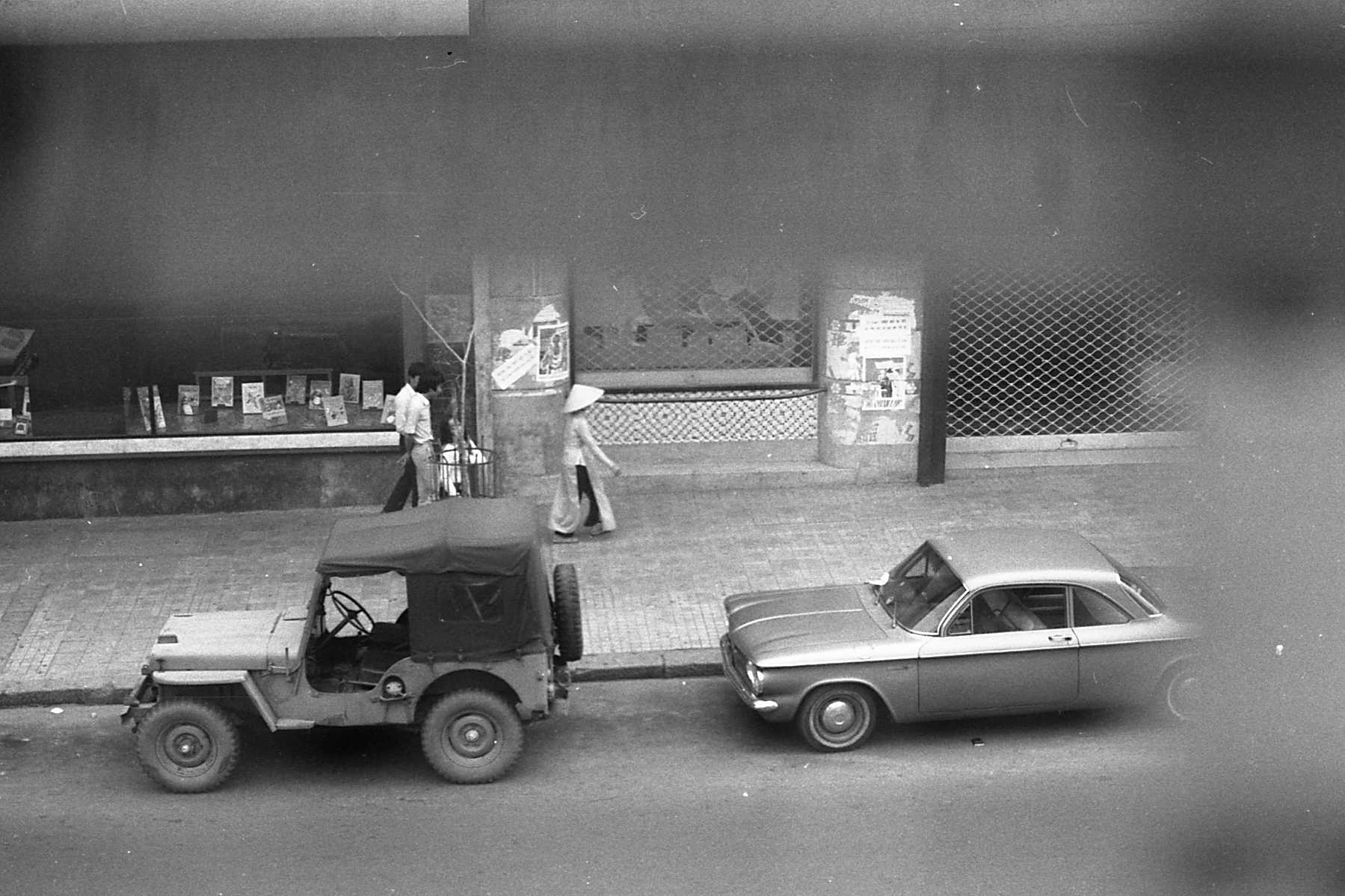

We were able to rent a one room second floor apartment looking out on Tu Do street, adjacent to the Continental Hotel. It was, fortunately, air conditioned. It had to be, since we were forced to keep the single set of windows facing Tu Do closed because of the noise and pollution. It was ideally located but somewhat dingy and claustrophobic. This would be our base in Saigon for the next year. In 1971, the view of Tu Do street was of the modest Xuan Thu book store across the street, and the since-demolished Passage Eden arcade, with its once-fashionable shops selling imported luxury goods. The bureaus of Time, Newsweek, the New York Times and the Washington Post were within a half a block of our apartment, and I made good use of this proximity during our stay in 1971.

.

Our 1971 apartment on Tu Do street. On the upper right of the picture, painted white, is the corner of the Continental Hotel. Our apartment is in the tan colored second story block above the ground floor businesses, with awning (second to left of the corner of the Continental Hotel and in photo below right). Le Thanh Ton street is on the far left of the photo. The entrance to the apartment was around that corner, through a non-descript alley (below). Photos DE

Xuan Thu bookstore on Tu Do viewed from our apartment. Photo DE

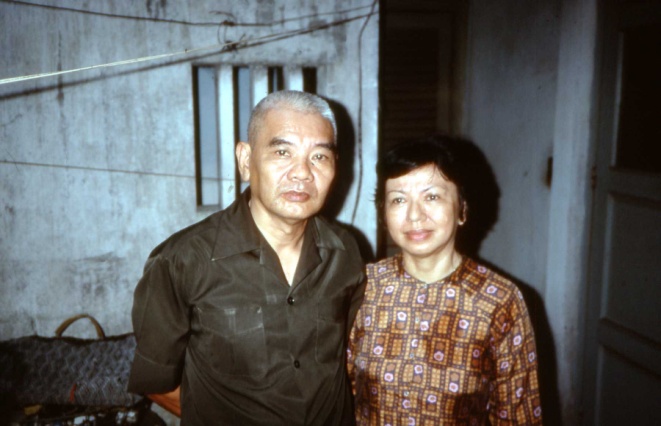

Having made the connection with MACV and settled into our living quarters, my next move was to find a way to reestablish our former connections in My Tho so I could begin interviewing. The first step was to contact Vuong Bach, who had been one of the three key interviewers during the first phase of the Rand My Tho project. By this time, Nguyen Huu Phuoc had been reinstated in the army and promoted to full colonel, and was now serving as the commander of the Regional Forces Training Center in Ben Tranh district of Dinh Tuong province. Dinh Xuan Cau, who had been a pillar of the previous project, was fully engaged with various entrepreneurial and political projects.

Bach turned out to be absolutely indispensible to the second phase of the My Tho project. Not only did he do the bulk of the interviews – with customary insight and sensitivity, but he was the one who made the connections with the Vietnamese government, without which the project would have never gotten off the ground. His key contact was his political patron Nguyễn Tiến Hỷ who, was a minister of state without portfolio in the government of Nguyen Van Thieu, which allowed him to network in any branch of the government he chose. The question of access to the My Tho Chieu Center was arranged by Bach through Nguyễn Tiến Hỷ, who had obtained his position in the Thieu cabinet in recognition of his longstanding leading role in the Viet Nam Quoc Dan Dang (VNQDD) political party and achieved political prominence as a member of the Caravelle Group, opposing Ngo Dinh Diem in the early 1960s. Bach had a different entrée into the local Dinh Tuong Police. His Saigon political connections included Đỗ Kiến Nhiễu, the mayor of Saigon, who came from the upper Delta and whose younger brother Đỗ Kiến Mười was the police chief of Dinh Tuong province. Bach thus obtained carte blanche to interview any prisoner in the province. Thus the whole project was arranged through Bach’s political connections.

Vuong Bach (right) and friend in front of My Tho house at 27 Hung Vuong, circa 1971 Photo DE

Bach’s effectiveness as an interviewer was magnified by the fact that he brought with him an assistant named Nguyen Van Thi, who did much of the leg work in arranging interviews, and was himself a proficient interviewer. Bach also had a network of family and retainers who transcribed his interviews, significantly increasing the productivity of our small group in My Tho. We ended up producing nearly one hundred interviews from the beginning of March to the end of August, 1971. Rand certainly got its money’s worth.

Nguyen Thi (left). Vuong Bach stands next to him. Circa 1971 Photo DE

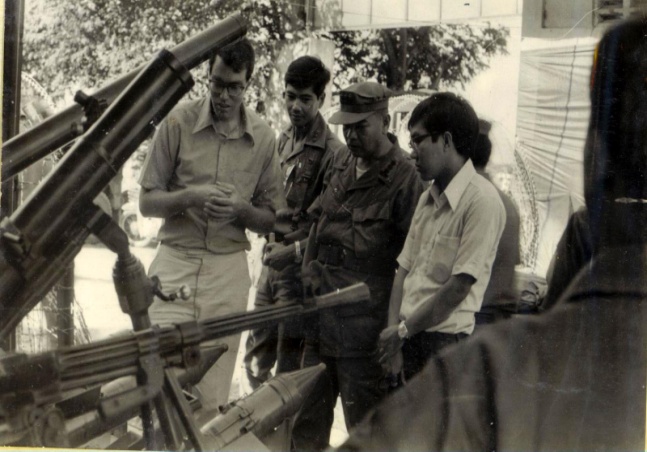

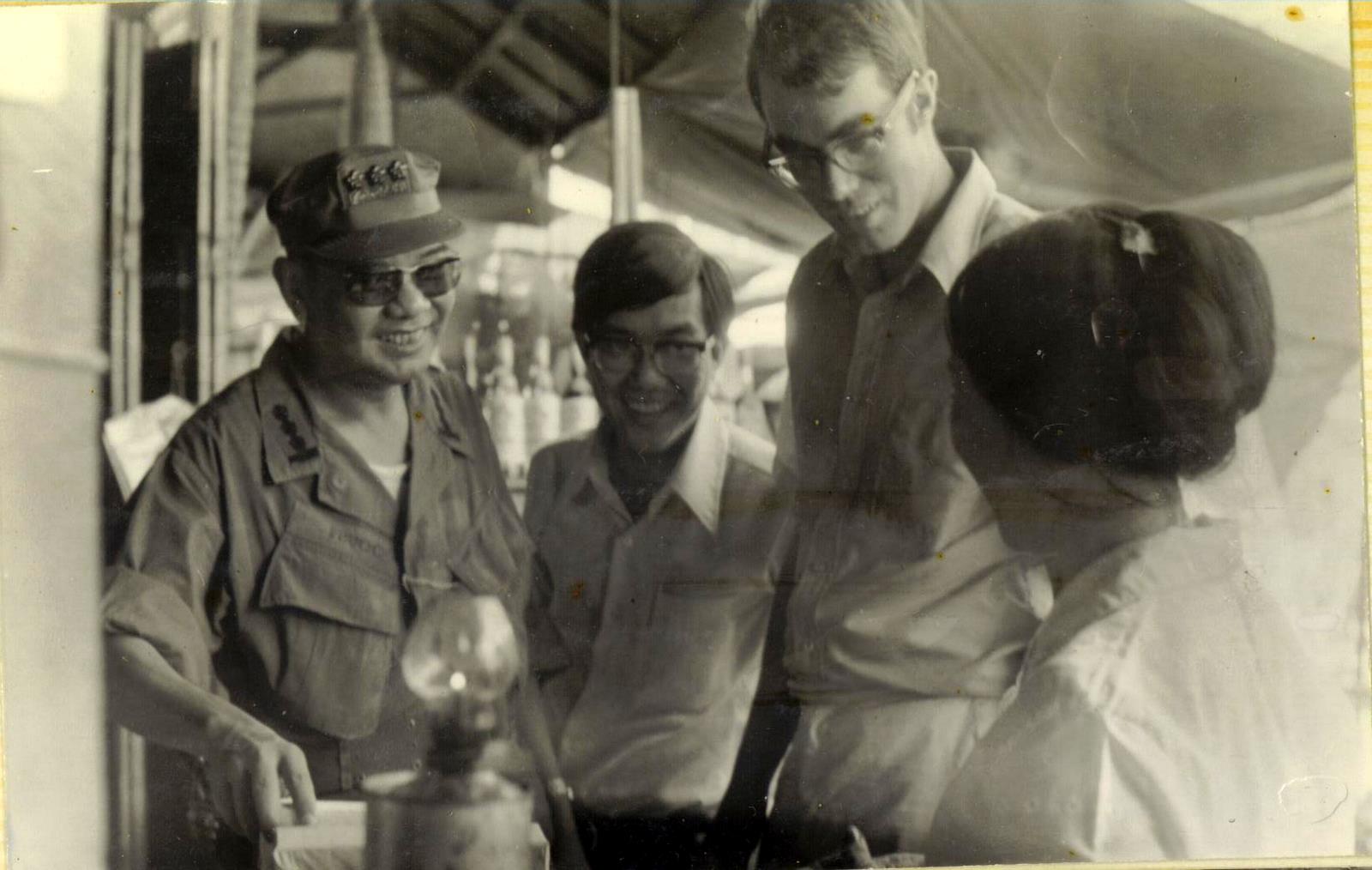

Ben Tranh district chief (left). Next to him is Vuong Bach, Nguyen Huu Phuoc was commander of the Ben Tranh Regional Forces Training Center, He is using a cane as a result of injuries sustained during a recent failed assassination attempt instigated by ARVN officers whose interests had been affected by Phuoc’s refusal to tolerate or participate in the graft that had become institutionalized. Nguyen Thi is on the right. Photo DE

Col Phuoc, Ben Tranh District Chief, and DE

I rented a modest sedan, far less roomy and grand than the Citroen I had once rented from Phuoc, to facilitate our commute to My Tho as well as transportation within My Tho. At first Bach and I stayed in the local hotel, and even did interviews there. Eventually I contacted our former landlord, who had now been promoted to Lt. Col. (he was a second lieutenant when we first arrived in My Tho in 1965) and arranged to rent one half of his duplex once again. This time Mai did not join me in My Tho. I worked in My Tho during the week and returned to Saigon on the weekends.

Rented red car in background on road to Cho Gao. Nguyen Thi is second from right in back row. Photo DE

I made a protocol visit to the province chief Le Minh Dao (but did not pass on Bob Komer’s assurance that I was “one of his boys.”). I was impressed by the dynamism of Col. Dao, and also uncomfortable that I could not frankly tell him that I felt the future was bleak for the Saigon government, and that I did not see a happy ending, no matter how effectively he performed. This turned out to be prophetic, when he courageously provided the last effective military resistance to the communist forces before they swept into Saigon on April 30, 1975. Unlike the previous stay in My Tho, this time I was not there in a joint effort to find a way to win the war, but rather as pessimistic observer whose main objective was to document the end of a tragic historical chapter and fill in some of the gaps in the previous research now that I had a better idea of what issues to explore. I simply told Col Dao that we hoped to continue our study of the Viet Cong movement in the province that we had conducted in 1965-68.

My changing views on the war also affected my relations with the US advisory team in Dinh Tuong. Unlike the 1965-67 period, where I had close ties with the province advisory team, and was on good terms with both of the province senior advisors who served during this period, I had a rather distant relation with the 1971 senior advisor, John Evans, a civilian official (the military senior advisor position had been phased out during the course of “Vietnamization.”). Evans quickly saw that I would be little use to him, and my presence in his area of responsibility seemed to be just another headache he had to endure. I, in turn, felt that Evans was clueless about the Vietnamese situation in his province, and seemed to be focused on making himself look good to his superiors by presenting a rosy picture of the situation. Needless to say, he was not receptive to anything that challenged this view.

First Impressions

In the first phase of the Rand interviews starting in 1965, our initial impressions were misleadingly shaped by what turned out to be a one-time event. The majority of the first twenty or so interviews were with a flood of defectors who had been dragooned into military service as part of a short-lived Viet Cong attempt to mobilize new recruits from the Mekong Delta to send to battlefields in Central Vietnam to obtain decisive military victories before the U.S. could intervene. As discussed in an earlier chapter, this strategy was quickly abandoned when the U.S. did intervene in Vietnam, so the flood of deserters who managed to escape en-route to Central Vietnam and return to Dinh Tuong that we first encountered was actually an echo of a previous decision that had been reversed, and not of current realities. So, in 1965, we got off to a slow start, and did not begin to get a better grasp on the situation until we had been interviewing for several months.

There was no equivalent group in the Dinh Tuong Chieu Hoi center when we arrived, so we were confronted with the task of piecing together a picture of the current state of affairs by laborious gathering of impressions from the interview subjects that were available to us, most of whom were fairly low level hamlet cadres. The exception was the very first interview Bach did in early March 1971 with the former village Party Secretary of a village right next to the recently constructed Dong Tam base of the U.S. Ninth Infantry Division, which had been withdrawn from Vietnam in July 1969.

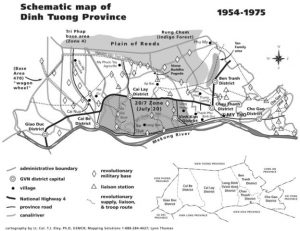

My Tho city is the white rectangular patch on the right side of the map. The Dong Tam base is the white area at the left. It borders on Binh Duc village to the east, where DT301 operated. Each grid represents a square kilometer.

We had no way of knowing it at the time, but this first interview previewed many of the important themes that ran through our subsequent research. His account of the security situation in this area, a supposedly secure zone less than ten kilometers from the province capital, alerted us to the complexities underlying the apparent pacification of most of Dinh Province. It was true that the number of Viet Cong cadres in the area had been dramatically reduced by the Ninth Division and Saigon security forces since the 1968 Tet Offensive, and that the revolutionary movement’s capacity to operate in villages like Binh Duc in this area had been drastically diminished. Given its geographical position, right next to the big U.S. military base, and as a key to controlling the road that connected the base to the province capital, this was to be expected. On the other hand, remnants of the Viet Cong “infrastructure” in Binh Duc still managed to hold on. (I titled my chapter on this 1971 period in The Vietnamese War “Holding On.”). This implied that while the Viet Cong were down, they were not out, and the war was far from finished. The term the Vietnamese used was bám (to cling to something, like a leech) or bám ruộng – to “cling to the ricefields.”

Since we had completed nearly 300 interviews in the first phase of the Rand study (1965-68) I numbered our interviews in 1971-72 as a continuation of the earlier series. The first of these, DT [Dinh Tuong] 301, was a young man, 24 years old, who was typical of the post-Tet generation of new recruits to the revolution to replace the 1960 generation of local cadres that had been largely killed off by 1971, especially in the period during and after the 1968 Tet Offensive. Ironically, he had joined the Party in October 1969, the very month the Binh Duc village Party Organization was formally disbanded. His rapid promotion to the rank of Village Party Secretary in 1970, even though there was no formal Village Party Chapter was, he said, due to the high attrition of local cadres. He did not have any formal training – which would have been unthinkable in the pre-Tet 1968 period. In the event, the district authorities soon discovered that he could not handle the complex duties of a Village Party Secretary and, in any event, there was no formal Party organization in the village. So he was reassigned as the political officer of a newly established village armed propaganda unit – a throwback to the 1959-60 period when such paramilitary units were the spearhead of the revolutionary movement as it attempted to gain a toe-hold in Dinh Tuong’s villages.

DT301 confessed that his level of political understanding was low, and that he mainly occupied himself with the tasks necessary for self protection. Despite his limited political sophistication, he did grasp and approve of the major objectives of the revolution. At first “when the VC cadres came to the village I was kind of frightened, but when I went to meetings and listened to them I began to have sympathy for them. I respected the Village Party Secretary the most because he was spell-binding when he spoke. I understood him right from the start. He talked about class struggle and volunteering to rise up to fight the GVN. Every family would benefit from the revolution, and in the future everyone would have enough to eat and wear.” His family, however, was concerned that they would get in trouble with the Saigon government if they discussed the revolution, and didn’t want their son to be politically involved on either side. But the success of the Tet Offensive in the villages of Dinh Tuong (the GVN forces had been compelled to withdraw to help defend the province capital, leaving a temporary power vacuum which was filled by the Viet Cong), like Binh Duc, encouraged him to join the guerrillas. There were only a handful in Binh Duc even in 1968 – each hamlet had one or two cadres and two or three guerrillas who were dispersed in order to maintain a more extensive foothold. DT310’s story was significant in that it indicated that recruiting was still taking place – enough to keep the revolutionary movement on life support. It was also significant in that he did not come from a family with a background of revolutionary sympathies or involvement, indicating that there was a potential recruiting base beyond the shrinking circle of longstanding Viet Minh and Viet Cong supporters.

By October 1969, a combination of a corruption scandal involving tax money and the killing off of local cadres let to the disbanding of the local village Party organization in Binh Duc village. A village armed propaganda unit was formed. This is usually a paramilitary force used in transitional situations before the revolutionary forces have gained full control of a village. The Binh Duc armed propaganda unit which combined military and political action thus represented a backward step from the period where there was a full-fledged revolutionary organization, led by a formal Party Chapter, but it was different from its 1959 counterparts in that it did not attempt to engage in political persuasion or mobilization of the villagers. Its main function was to protect higher level cadres when they periodically came in to collect taxes, which the local cadres no longer did because of the corruption scandal and the lack of capable cadres. The fact that there had been a corruption scandal was itself an indication of the declining effectiveness of the village Party organization, which was no longer able to keep such abuses in check. Moreover, the reliance on armed forces who were not native to the village created uncertainty among the villagers. DT301 revealed that “roving gangsters posed as tax collectors to shake down the civilian population. This made life more difficult for the genuine guerrillas, because the high turnover and secrecy had made it difficult for the people to tell who really represented the revolution, so the armed team coming to collect was often greeted with suspicion.” Nevertheless, the revolution continued to collect taxes, even in nominally Saigon-controlled areas.

Despite the weakness of the revolutionary movement in Binh Duc village, other villages on the other side of the Dong Tam base, farther away from the province capital. Thanh Phu and Long Hung village had a total of 30 to 50 guerrillas. But unlike the early and mid 1960s there were only a few scattered dispersed higher level military units to support them, and these spent most of their time on the outer fringes of the province, far from Binh Duc. These local guerrillas carried out the functions that civilian supporters had once provided the revolutionary movement, such as liaison agents linking the villages and hamlets to the districts. They were slower and more cautious than the civilians, who could more easily blend into the landscape, but still managed to hold the remnants of the revolutionary movement in the area surrounding Dong Tam together, despite the near crippling of the movement in DT301’s village of Binh Duc, where his defection left only two surviving Party members in the village. Having lost control over most of the village, the revolutionary movement was reduced to sporadic tax collections by sudden penetrations into GVN controlled portions of the village which sometimes resembled home-invasions by a marauding external force, without the backing of the community pressure that had been effective when the Party presence in the village was stronger. But the mere presence of 30-50 guerrillas in two villages on the western side of the major military base in the province was evidence that “pacification” was not complete.

This interview with DT301, the first that we did after my return to Vietnam, also previewed what we came to understand as the central feature of the security situation in Dinh Tuong in 1971, two years after the departure of the U.S. Ninth Division: that the “pacification” that had produced the apparent security in the province had been achieved not by extending Saigon’s control throughout all the villages of the province, but by compelling people in outlying areas to relocate to areas surrounding GVN centers of control such as roads and military posts. This was done through a combination of indiscriminate bombing and shelling, which made life in many areas not directly controlled by the GVN intolerable, and also by military operations that directly compelled peasants to dismantle their homes and move them to areas more easily controlled by Saigon. It was, in short, Sam Huntington’s “forced-draft urbanization” with bombing and shelling and coerced population transfers rather than industrialization driving the depopulation of the countryside. Pacification by forced population transfers left open the question of whether or not the GVN would still be able to control these displaced peasants if the situation became secure enough for them to return to their former hamlets and villages.

DT301 noted the impact of the post-Tet surge in US and ARVN military operations, and said “they caused a lot of difficulties for the people, destroyed their crops and belongings with the bombings and shellings, and this is why the people had to suffer privations. If they stayed in the liberated areas they wouldn’t be able to earn their living, so they had to flee into the strategic hamlets.” By “strategic hamlets” he did not mean the Diem-era enclosed hamlets surrounded by fences and moats and sharpened bamboo stakes (which had not been prevalent in the Mekong Delta, where hamlets were strung out along roads and canals rather than concentrated in compact settlements as in some other areas in Vietnam). Rather “strategic hamlets” typically referred to an agglomeration of thatched roof huts surrounding a local militia post, or clustered along roads.

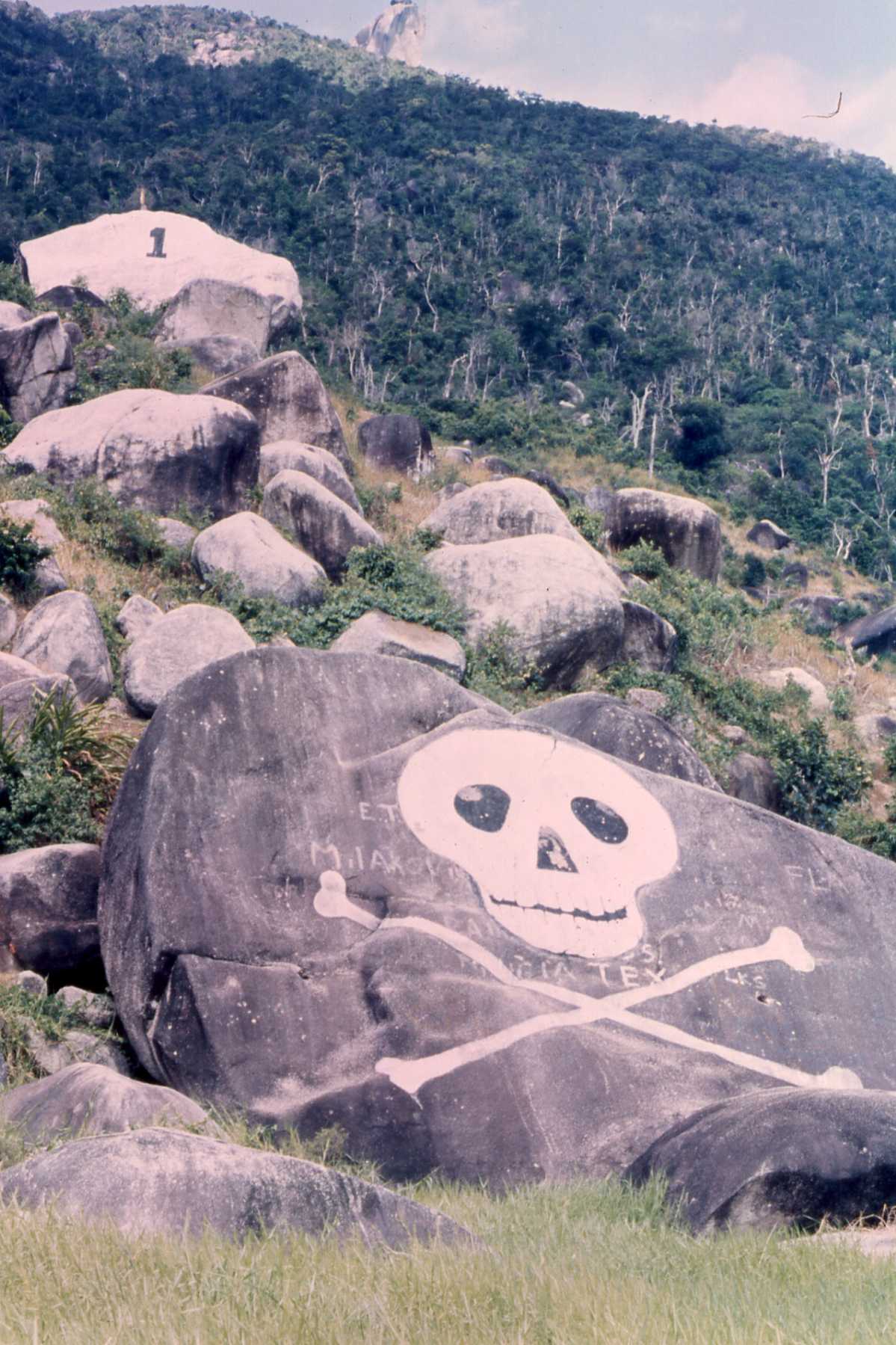

Hamlet settlement in Cho Gao district 1971 Photo DE

GVN military post and scattered settlements along a canal in the northern part of Dinh Tuong province, 1971. Note the profusion of bomb craters. Photo DE

DT301 showed that despite his desertion, his sympathies still lay with the revolution. The people, he said “didn’t resent the Front. If they had to be far away from the troops and the revolution it was only because the GVN campaign had separated them ‑ if the people returned to their orchards the ARVN would investigate them and suspect them and then arrest them and beat them up. So the people were afraid to have contacts with the revolution only because they were

afraid of these hardships not because they either resented the revolution or the cadres.”

This first interview of 1971 alerted me to the complexity of the situation. First of all, one couldn’t reliably infer political disenchantment with the Viet Cong from the simple fact that a “rallier” had defected. Second, the account of DT301 raised the possibility that there were submerged reservoirs of support for the revolution, despite its apparent quiescence. One of the main points made in both the interim and final report on these interviews was that the Viet Cong were down, in 1971, but not necessarily for good. Should the situation change, as it did in 1972, the submerged support for the revolution might resurface. In short, the war was not over, as many “optimists” had concluded in 1971.

DT301 told us “at present Front forces are entrenched in every village even though the GVN is defoliating, cutting down the orchards and attempting to attract the people, they only encroach a little on the liberated areas. GVN soldiers don’t dare penetrate deep. In Binh Duc village GVN soldiers have penetrated only a few hundred meters into Ap Dong hamlet and are only able to shell liberated areas.” Several trips around the province revealed how costly these clearing operations were for the GVN soldiers, who suffered debilitating losses themselves while operating in an environment of mines and booby traps.

GVN casualties suffered in clearing operations in 1971 were demoralizing. Photo DE

Toward the end of our research, Bach’s interview with a Region level cadre confirmed this picture of “holding on.” In many outlying villages the constant bombing and shelling forced the peasants to flee to GVN controlled areas. Although the cadres urged them to return or at least commute back and forth to tend their fields, the fear of being caught in the fighting ultimately discouraged them from doing so. In the end, it was mainly the cadres who were able to “hold on” in the areas they had once controlled and administered. But they continued to maintain a presence in 1971 and waited for better days.

It took nine months and nearly 100 interviews to corroborate this story, but it is remarkable that we should have encountered this fairly accurate overview of the complexity of the security situation in Dinh Tuong on our very first interview. What added to his credibility was that he was very open about the weakness of the Party in his village even as it managed to “hold on.” “The thing that I was most sad about was being unable to hold firm the people’s sympathy (giữ vững được lòng dân) and to motivate and attract people into the organizations of the revolution.” The depopulation of formerly “liberated” hamlets had caused the dissolution of the popular associations (farmers, women, and youth) which had been the foundation of the revolutionary movement, leaving only a skeleton organization comprised of the remaining hamlet and village cadres.

Although the GVN had gained dominance in Dinh Tuong by 1971, it had reached the peak of its power and was not able to translate this dominance into an end-game that would conclude the conflict. The Viet Cong were in a substantially weakened position compared to earlier years, but they were still able to sustain a stalemate by clinging to the villages and hamlets of province despite the GVN’s efforts to finish them off.

Filling in the gaps: Reconstructing What Had Happened in Dinh Tuong since the Earlier Rand Study

Although I happened to be visiting in Vietnam at the time of the 1968 Tet Offensive, we had already moved to Taiwan in late 1967, and I had submitted a report on the My Tho project to Rand at this time. A few interviews were conducted in late 1967 and into 1968, they were not incorporated into the report I wrote for Rand. There was nothing that I had seen that would suggest something as audacious as the Tet Offensive. The Viet Cong movement was being slowly ground down in Dinh Tuong, and the U.S. Ninth Division had just moved into its Dong Tam base. The devastating attack on the town of My Tho was totally unexpected, and I had learned nothing prior to my return in 1971 that would explain what had happened and how it had been possible, given the weakened position of the Viet Cong in the province. Finding answers to these questions was one of the primary tasks in “filling in the gaps” about the period between fall 1967 when, for all practical purposes, the research and analysis of the situation in Dinh Tuong ended, and our return in February 1971.

The Vietnamese War described the impact of the Tet Offensive in My Tho in the following terms: “When the Tet attack by the revolutionaries hit My Tho on the night of January 30–31, 1968, only the presence of special detachments providing security for President Thieu near the province compound, and some tactical mistakes by the attacking revolutionary forces, saved the city from being overrun. Only on the second day of the offensive, when President Thieu was evacuated to Saigon by helicopter, did the attacking forces become aware of his presence in the town. This was one of many unforeseen circumstances which undermined the Party’s offensive plan. The two lead attacking regiments were driven out of the city after three days by a determined defense of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and by province forces and, ultimately, by devastating U.S. firepower. Of Ben Tre, the province capital south of My Tho across the Mekong River, a U.S. major reportedly remarked, “It became necessary to destroy the town to save it,” but the same might have been said of My Tho. The U.S. advisory team in Dinh Tuong reported after the first week of the offensive: “An estimated 25% of the city was burned, 5,000 residences have been destroyed and 25% of the people are homeless. The psychological impact of a calamity of this importance cannot be measured so close to the event, but it is obviously enormous.”

“In the excitement, shock, and turmoil of the nationwide revolutionary offensive, and the natural focus on the major cities, what was happening in the countryside went largely unreported. By the time the situation had stabilized in late spring of 1968, the extraordinary turnabout that had occurred in the villages of My Tho had subsided. However, perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the Tet Offensive in My Tho was that the demoralized and increasingly passive civilian population in the rural areas participated energetically, and often enthusiastically, in tasks which they had shunned during the previous year. This view from the villages is the main missing dimension of most accounts of this critical turning point of the war. Another important point raised by the Tet Offensive in My Tho is what it can tell us about how the local situation in the province fit into the ‘big picture’ of the war.” The surge of revolutionary enthusiasm following the peasants’ increasing political apathy prior to the Tet Offensive was less a resurgence of political sympathy for the revolution than a drive to push the war to a conclusion and bring about peace. In 1971 I took note of the fact that overwhelming dominance of the GVN had not stimulated a similar bandwagon of active support from the civilian population, perhaps partly due to lack of political sympathy with the Saigon government, but also probably due to a pragmatic conclusion that the GVN would be unable to achieve a definitive victory.

This “untold story” of the Tet Offensive, the remarkable and sudden regeneration of the revolutionary movement in Dinh Tuong province outside the urban areas, was a significant revelation to us as we attempted to fill in the void that had been left by our suspension of interviewing in 1968. The implication of this revival was that there were deep reservoirs of support for the revolutionary movement, and however beaten down it might appear at specific times, such as 1971, there was always a possibility of recuperation if circumstances changed.

The extent of the dislocation of the civilian population in the province became increasingly apparent as the interviews progressed. The process of depopulation often started with the decision of rural residents to move from their traditional homes in the shady orchards to temporary straw huts in the middle of the ricefields, because the orchards and treelines were under constant bombing and shelling as suspected Viet Cong military campsites. In some cases, the orchards were simply cut down, and the houses forcibly removed. By 1971 the GVN was forcing peasants living in temporary shelters in the middle of the ricefields to dismantle their huts and move into GVN controlled areas near posts or along the roadside.

DT301 suggested that the very success of the GVN in blanketing the province with a network of small militia posts created problems which were not apparent to most external observers at the time, but actually benefitted the Viet Cong in their struggle to “hold on” until a more favorable situation developed. In some ways the GVN success in setting up a network of posts was a contributing factor in this failure to take advantage of the military weakness of the revolution. The posts made Saigon complacent and reduced the scope and intensity of GVN ground operations, leaving the cadres and guerrillas with safe havens and some respite. The Binh Duc leader described the change caused by the departure of U.S. troops. “When the Americans were still here, their regular troops were very active so they didn’t need to set up posts or to have many units operating. They only relied on aerial bombings day and night without letup, and sent their ground troops deep into liberated areas. After the Americans withdrew, the GVN set up many posts. Each village built something like eight or nine posts, whereas the Americans used to have only two or three posts at most. The increase in the number of posts created a lot of obstacles for the VC [but] before, the Americans used shellings and bombings to the maximum and were only concerned about protecting their bases and barracks, so it was easy for the Viet Cong to hide, provided they built fortified bunkers.” Still “The increase in posts restricted the VC from carrying out their attacks a lot” [DT301].

The Region cadre interviewed by Bach (DT313) confirmed the remarkable capacity of the cadres and guerrillas to fit themselves into the interstices between GVN military posts and continue to operate under the noses of their adversaries. He stated that “the building of posts has reduced the area of operation of the cadres, and caused the Front a lot of difficulties. At present, the Front occupies the gap between the posts as its base of operation; for example, there are three posts in three corners, and the Front people live in the area in the middle where they plant mines and booby traps, and apply guerrilla warfare, etc.”10A special operations cadre from North Vietnam who operated in the western part of Dinh Tuong in the 1971-75 period described to me how his unit operated under the noses of a nearby GVN militia post and showed me a picture of himself taken in 1971 surrounded by unit members grouped around a table with a radio calmly listening to GVN radio transmissions from a military post only 350 meters away from their own camp.

Revolutionary dac cong fighters monitor GVN radio communications from the A Rac militia post in My Duc Tay village only 350 meters away.

When Sáu Đường, the party leader for the provinces of the central Mekong Delta travelled from the revolution’s base area in the Plain of Reeds to the villages in the so-called 20/7 Zone west of the massive American military base, between Highway 4 and the Mekong River, the very heartland of Dinh Tuong province in late 1971, “every hamlet in the 20/7 zone was covered with posts. Everywhere you looked there was the [GVN] yellow three striped flag flapping from high observation towers—you could even see the soldiers standing guard on them.” When Sáu Đường later described this situation at an expanded meeting of the Politburo in Hanoi in 1973, his listeners were stunned and skeptical.”11 Even these hardened veterans of guerrilla war could not grasp the close-quarters conditions in which the Dinh Tuong revolutionaries were “holding on.”

Echoes from the Past

As we filled in the gaps of the historical evolution of the conflict in My Tho province, it became evident that this history had a powerful effect on the calculations of the peasants, as they assessed their present and future prospects and attempted to figure out what to do to preserve their interests while caught in an unpredictable conflict. We found it intriguing that many older interviewees mentioned previous instances when the revolution had been in a perilously weakened position. It was these recollections of a series of past recoveries from adversity that underlay the theme of a potential dramatic recovery from the revolution’s decline in Dinh Tuong in my preliminary and final report to Rand. Another factor was the ARVN setback in the disastrous invasion of Lower Laos which happened just as I arrived back in Vietnam, and provided an example of the kind of military setback that might start to unravel the position of temporary GVN dominance.

One of the illustrations of the revolution’s recuperative powers was in the last years of the First Indochina War. By 1952 the Mekong Delta appeared to be nearly pacified. But by late 1953 the situation elsewhere in the country began to shift against the French, and by 1954 this adverse tide had reached the Delta, and revolutionary movement experienced a resurgence of strength. My later research confirmed what the interviewees told us in 1971, that during the last months of the First Indochina War there was a dramatic resurgence of revolutionary power in the Mekong Delta. My Tho’s province Party history contends that by the signing of the Geneva Accords in July 1954, almost the entire rural area of the province was under Viet Minh control, as well as many of the secondary roads in the province.

The French military’s assessment of the situation in the Mekong Delta at the time the Resistance War ended was that pacification remained “fragile”: “Its eventual success requires a perseverance which we sometimes lacked. A characteristic example of this is the deterioration of the situation in Cochinchina during the last months of the war. At that time there occurred a renewal of Viet Minh military activity that would have required the initiation of a new pacification campaign. ‘Only the zones held by the sect forces remained relatively healthy; all other zones supposedly under our control became gangrenous.’ ” As A.M. Savani, the French intelligence officer who chronicled this period pointed out, however, in the end even the anti-communist religious sects abandoned the colonial cause.12

Another historical lesson about the transitory nature of attempts to suppress the revolution was the Diem regime’s attempts to eliminate the residual Viet Cong movement during the “Anti-Communist Denunciation Campaign of 1956-59. During this period, large numbers of Viet Minh, both current and former members, were arrested and incarcerated for several months of indoctrination, only to be subsequently released. This campaign’s main impact was to prove to these former Resistance fighters that they had no place in Ngo Dinh Diem’s South Vietnam and they would have to resist for survival. It was this group that became the nucleus of the Viet Cong insurgency in 1959-60. An even more recent example of Viet Cong resilience was their recovery from the setbacks of 1962 when stepped up US military aid put the revolution on the defensive until they devised ways of responding to the new counterinsurgency tactics of helicopters and armored personnel carriers in the battle of Ap Bac, January 1963.

These historical memories, recounted by many of the interview subjects, indicated to them that the down turn in Viet Cong fortunes in Dinh Tuong in 1971 was temporary. As the Region cadre interviewed by Bach put it, “The Front has had reverses before and has faced a loss of confidence before, such as at the time of the Strategic Hamlets when the cadres had to scatter, but later on the movement became strong again. Why did it become strong again? At that time the Front could motivate the people. According to the revolutionary pattern, the Revolution sometimes is up and sometimes it’s down. The more it goes down, the higher up it will go. If the Revolution has difficulties, it can overcome them if the village and hamlet machinery is still functioning.”13

If the ordinary peasants did not entirely share the confidence of people like this committed revolutionary, their own experience convinced many of them that the rebound of the revolution was plausible enough so that they had to take the possibility of history repeating itself into account. Thus, while a “rational peasant” (to use Sam Popkin’s term14) might be tempted to climb onto the GVN bandwagon as a way of protecting his interests, the record of the past suggested to many of them that this might not be a wise investment in the long term. A specific case was the response to the belated GVN “land-to-the tiller” program. In many ways this was a much better deal for the peasants than the Viet Cong land reform (which did not guarantee permanent ownership of the land and was accompanied by onerous demands for taxes). But it was only an attractive incentive to support the GVN if the peasants were confident in the long-term future of the Saigon regime, and many rural residents were not, in part because of these cautionary historical lessons.

An even more important reason for the limited impact of the “land to the tiller” program was that the war had depopulated much of the countryside. Landlords had abandoned their land, and often could not find anyone to cultivate what they had left behind. Much the land was in insecure areas, and was overgrown to the point that it could not be cultivated. DT313 said “The people clearly see that the government is doing something that is superfluous and useless. Superfluous because on the other side, the Liberation has always distributed land wherever it goes, and in fact, the problem now is not to give land to the tillers, but to end the war, the bombings and the defoliation, etc. There is now an excess of land, but there aren’t enough people to till it. The farmers have either taken up arms on this side or the other side, and others are so afraid of bombings and shellings that they don’t dare to go out and farm.”15

It was clear to many peasants that the land tenure situation would only be clarified when the war was definitively concluded, security restored so that peasants could return to their hamlets, and the question of who had to power to confer land tenure was conclusively resolved. Thus the appeal of land reform while the war continued was very limited.

“Farmer’s Day” in Ben Tre town, April 1972, celebrating the Land for the Tiller Program Photo DE

There was fragmentary evidence that such a return to the land was starting to occur in early 1972 after the forced exodus of the previous several years. The New York Times cited official American sources who stated that they expected that 200,000 civilians in the Mekong Delta would return to their villages. “The main motivating factor is that, at least for the time being, the countryside is safer. There are still occasional skirmishes but, over-all, fighting in the delta has tapered off. Most of the American bombers have gone home and less is heard from the Viet Cong.” The Times observed that “Whether the Vietcong have been incapacitated to some extent, as American and South Vietnamese military men say, or whether they are just lying low is hard to know.”16 The story was printed on March 20, 1972 but datelined March 9, three weeks before the coordinated assaults in Central Vietnam that opened the Spring Offensive of 1972 which brought the period of quiescence to an end throughout South Vietnam and largely halted any large scale return to the depopulated countryside.

We discovered that for many peasants, both those who stayed in their hamlets and those who became refugees, the deepest appeal of the revolutionary movement was not its revolutionary political program, or the promise of material benefits, but the fact that in many rural areas it represented a force committed to preserving traditional village ways in a society that was being assaulted by disorienting social change. Although much of the revolutionary movement’s one-time supporters had been dispersed into quasi-urbanized settlements (“forced draft urbanization”) those who remained in the more remote villages felt alienated by the social transformation that they saw in the towns and cities.

In this regard, the GVN was more an agent of “modernization” and social change than the “revolutionaries,” who in these circumstances were social conservatives. It was telling that most interviewees used the terms “in there” (ở trong kia) and “out here” (ở ngoài này) when referring to the former liberated areas, primarily remote villages far from the main roads, and the GVN controlled areas, the towns and market villages along the main roads. This implied that “in there” was closer to the core of an authentic Vietnamese identity, while “out here” was an artificial or external environment. For many rural peasants, the Saigon controlled areas constituted an alien world.

It was difficult to document this, but one memorable illustration was an interview I had with a civilian prisoner, who had been a village cadre in a village which linked Highway 4 and its urbanized settlements with the more remote rural hamlets bordering the Plain of Reeds. A cadre from Nhi Binh village, [DT312] with a strong revolutionary tradition, described how negative urban social influences reached the village and described how Vietnam’s society was become divided not only by politics but by culture, rural and urban. “Those who have fled to the towns have been greatly influenced by the outside. Those that stayed in the local area are very simple and hardworking. They earn a plain and honest living, and wear ordinary clothes as they always have.” The peasant cadres would lecture those returning from the towns on clothing styles. “We are peasants, and should dress plainly and simply.” Plain dress and polite speech were the hallmarks of the virtuous rural society. “As for running after the social trends out there,” said the cadre, “that means wearing really thin clothes, and false breasts, which induce sexual excitement when young men and women get together.” For the most part, the children of families with a “revolutionary tradition” did not succumb to the lure of the cities, said DT312. Village cadres tried to get the young people returning from the towns to change their ways and go back to the old rural style of dress. The youths replied that “Living out there in the Saigon society, we have to keep up with the other people. If we dress like that they’ll call us bumpkins and cut us dead [coi mình là quê chết].” For young women, living in the cities could offer financial rewards beyond the imagination of the simple peasants. Being a prostitute with an American clientele could bring in 30,000 to 40,000 piasters a month, “so that when girls from ordinary peasant families returned they lived a luxurious and decadent life. But in comportment, the home-grown girls far surpassed them” [DT312].

Most of the urbanized youth returning to the villages were women, since the young men were either drafted by the GVN, evading the GVN draft in the anonymity on the cities, or afraid to return to the villages for fear they would be drafted by the revolution. These young women were subtly ostracized.

They were isolated. Take the case of a relative of mine named Miss Khoa. Her father had been a Saigon soldier. When the Concerted Uprising came, she married a village guerrilla, and they had a child. He was pulled up to the concentrated units, and she left for the town. First she “married” an American, had a child, and then they split up. Since then she has “married” two or three other husbands, and this has deeply affected her in-laws [family of the former village guerrilla]. When she first came back to the village the cadres told her that if she mended her ways and returned to the right path they would help her out financially. When the revolution succeeded, they would send a cadre to persuade her husband to forgive her. She replied that she had left her first husband and had rebuilt her life. After that, she didn’t dare come back often, but at Tet or at family death anniversaries she would return. It appeared as though she wanted to win the sympathy of her relatives, but I saw that though they didn’t say anything in front of her, they talked about her “hippie” [form fitting, bell bottom pants] pants, which the peasants really hated. In my view, her intention was to impress the people by dressing like that, but it ran counter to their psychology. This young woman didn’t have a deep understanding of the peasants’ feelings, because she was still young and didn’t understand the traditions of our people [DT312].

Because she had become accustomed to the cultural patterns of the Saigon lifestyle, Miss Khoa could not recognize the social cues and subtle putdowns of the peasants. Despite their reserved reception, she didn’t get the message. “Our people have a very special characteristic,” said the cadre. “They can meet someone and exchange pleasantries and be very soothing. [They would say to the girl,] “Well! Before you were so plain, but look at how beautiful you are now, with all that makeup, and with your shoes and sandals [most people went barefoot in the villages and shoes or dressy sandals were regarded as an affectation] and beautiful clothes!” In my view the people were being sarcastic, but she didn’t understand. There were five or six episodes like this” As he recounted this story, DT312 clearly relished the opportunity to underscore to me, his American interviewer, the extent to which the Saigon government had become the promoter of cultural degeneration.

The peasant conservatism characteristic of most revolutionary cadres made it difficult for them to operate effectively in an urban environment. A region level cadre who was assigned to operate on the outskirts of My Tho described the problem which he had witnessed in his work. “Unfortunately, the male and female cadres coming in from the countryside didn’t understand that using obscene language was a common thing as far as the urban people were concerned, because the city wasn’t revolutionary territory. As for the thing which the City Party Committee strongly stressed, ‘creating a revolutionary nucleus’ and ‘exploiting the class oppression,!’ The female or male cadres coming in from the countryside couldn’t see the problem clearly, and refused to make contacts when they saw things that offended them. For example, many of the girl students or the 19 to 20-year old girls in the city were dressed and acted like actresses, and the cadres found them ‘offensive’ since they weren’t used to such sights. They were irritated and put off, and refused to make contacts. These difficulties were caused by the fact that the cadres from the countryside brought into the city with them the simple, virtuous, and traditional views of the countryside. When they went to the city, they found everything offensive, so how could they operate effectively? There were reasons why the cadres who went into the city were unable to do anything. They came from the countryside, they had never lived in a city before, and so they were unfamiliar with the language, the style of living and the activities of the people in the city. For example, almost all the female water carriers in the city had short hair. But female cadres who just came into the city from the countryside absolutely refused to cut their hair in order to merge with the life in the city. Or a cadre might have keen observation in the countryside, but when he went into the city and heard a pedicab driver use obscenities such as ‘F ••• you!’ etc., the cadre refused to contact him, thinking that the pedicab driver was immoral and a criminal–someone who couldn’t be used by, let alone recruited into, the Front. Unfortunately, the male and female cadres coming in from the countryside didn’t understand that using obscene language was a common thing as far as the urban people were concerned, because the city wasn’t revolutionary territory.” 17

At the time, we grasped the immediate problem easily. The peasant conservatism of the revolutionary movement, reflected in their cadres, made it difficult for them to relate to the urban “proletariat” – the pedicab drivers, day laborers, and female water carriers – despite their Marxist-Leninist ideology. Thus they were ineffective in recruiting the most obvious base of urban support for the revolution. This also explains why the Tet attacks on the cities failed to have a lasting impact, and diverted the revolutionaries from the opportunity to take advantage of the power vacuum in the countryside created by Tet, while the dogmatic Viet Cong strategists in Hanoi pressed for a continuation of the disastrous assaults on cities long after it was evident that this approach was a costly failure.

After the war, the lure of the cities and the appeal of “life in the fast lane” for many youths, which I describe in my chapter “Holding On” was a greater long term threat to the revolution than programs like land to the tiller, or the Phoenix program. The longer term problem became apparent only much later when the victorious revolutionaries failed miserably at transforming the cities into bastions of “socialism” and the urban styles and economy of the South ended up transforming the North – far too late for the Saigon regime or the Americans to savour the irony. For a lengthier discussion of this, see my account in Changing Worlds on the growing “Southernization” of Vietnam after the apparently conclusive victory of the revolution in 1975.

Fancy clothes and “far out” music were not, however, a sufficient motivation for those who enjoyed them to join Le Minh Dao on the barricades in 1975 to resist the onslaught of revolutionary forces about to overrun Saigon. Moreover, the social decay and urban decadence that was a by-product of the war turned many conservative Southern Catholics against the Thieu regime just at the time the American departure made it imperative that Thieu consolidate the strongest possible anti-communist political base possible.

Urban Politics and the Third Force

From the vantage of revolutionaries in the countryside the urban areas were regarded as decadent enclaves whose fads and fashions were eroding traditional Vietnamese values. This view was not confined to the countryside or to puritanical revolutionaries, however. The disorienting social changes wrought by the American presence in the cities increasingly alarmed some of the most stalwart anti-communists, who might have been expected to support the GVN. By 1971, there was widespread disaffection with the Thieu government even from some of the most anticommunist sectors of society. A former Diem official wrote a blistering attack on the “brothel society” for a Saigon newspaper that extolled the purportedly uncorrupted rural people, “who have maintained the tradition of their ancestors in opposing foreign aggression,” while excoriating GVN officials as a “gang of prostitutes.” Infuriated by the mysterious death of his brother, who had been killed for exposing corrupt practices, and his son, a medical student and opponent of the Thieu government who was also assassinated, this formerly zealous anticommunist wrote that “The yeast has already begun to rise. When the hamlets and villages become a base from which all the people can escape from the addiction to material goods, and the value of struggle and production is recognized, no foreign power can force us to become a Brothel Society.” After the 1973 ceasefire some fiercely anticommunist Catholics began to form what would become a formidable opposition to President Thieu on the grounds that South Vietnamese society needed to be purged of corruption in order to avoid a communist takeover.

Apart from the Catholic social conservatives, there were militantly anti-Thieu Catholics such as Chân Tín, Nguyễn Ngọc Lan, and Trần Hữu Thanh. Even by 1971, some moderate Catholics were turning against not only Thieu, but the Americans and the war itself. The probable catalyst was Thieu’s bald power-grab in the scheduled Presidential election of 1971, in which he disqualified his most formidable challenger, and ran uncontested, making a mockery out of the claims that America’s ally was progressing toward democracy. The New York Times noted the impact of this one-man election. “Among President Thieu’s enemies are the militant students, the intellectuals and the nucleus of deputies who hate him but who have so far not been able to hurt him seriously. Others are the organized disabled war veterans, and half a dozen minor peace groups that are often composed of Vietnamese who once had power or political influence. They have now been joined in their frantic but often feeble efforts to arouse the Vietnamese public against President Thieu by some factions of the Roman Catholics and by the strongest group of the nation’s Buddhist leaders, the An Quang faction. Leaders of the Hoa Hao religious sect – considered traditionally as anti-Communist as most Catholics – have this week also criticized the one-man elections.”[1]

As in the turbulent years of the mid-1960s, it appeared in the early 1970s as though there might be the possibility of a “Third Force” emerging between Thieu’s American-supported military regime and the communists. “‘Our politics today are completely unlike those of our past,’ Prof. Ly Chanh Trung said recently. He is a Catholic who teaches philosophy at the University of Saigon. ‘For the older Vietnamese, religion once came before the country,’ he continued. ‘Now for the younger Catholics the nation is just about as absolute as religion. Nationalists are those who cannot accept dependence on foreigners and more and more Catholics are saying no to the Americans.’” This evolution of activist Catholics from defense of the faith to political activism spurred some Buddhist groups to intensify their political opposition to Thieu.[2]

The idea that there was a moderate “Third Force” which might be an alternative to the authoritarianism and corruption of the Saigon government, and the harsh implacable repression of the communists had an obvious appeal to many Americans, who hoped for a middle ground solution that might end the war. For myself, even as my support for an increasingly unlikely Saigon victory faded, I could not envisage the weak and divided “Third Force” as an alternative, believing that they would be crushed by the communists when they came to power – which is, in fact, what happened. Still, one had to admire those who sought to end the war with a compromise solution for their decency and the courage of their convictions.

Among my American friends, Tom Fox was the one with the closest connections with the Third Force opposition to Thieu, especially among the Catholics. I had known Tom slightly during my first stint in Vietnam with Rand when he was a member of the International Voluntary Service (IVS). Tom had been an All-State athlete in both baseball and football, and had gone to Stanford on a football scholarship. A profile of Tom writes “At Stanford he found himself immediately drawn to the teachings of Dwight Clark, dean of freshman, a Quaker and a pacifist. “At that time I was a Catholic who believed, I thought, in just war.” He learned about nonviolence, started reading Thomas Merton, and listened to the songs of a young guitarist, Joan Baez, who would stop by the dorm to play and sing. She and Fox’s classmate David Harris eventually wed. In the break after his freshman year, Fox was one of 20 students Dwight Clark invited to visit Asia as volunteers. Fox went to his football coach to ask if he could go. The coach said no, he’d be too out of condition to play football when he returned. The sophomore-to-be went anyway, ending his football career. Before summer ended, however, he had received an academic scholarship.”[3]

I have an indelible memory of walking down a street with Tom and, as he related the story of the end of his athletic career, he nostalgically and reflexively pantomimed throwing a pitch, showing how much he missed that life. This showed me how deep his commitment to bettering the lives of others was, and what a steep price he paid to pursue it. After his stint with IVS, Tom got a master’s degree at Yale, and was then taken on by the New York Times as a stringer, launching the journalistic career that was to become his passion and vocation for the next half century. I recall reading the New York Times announcement of his wedding to a graduate of the elite private woman’s lycee in Dalat, Couvent des Oiseaux a month prior to our return to Vietnam in February, 1971.[4] Hoa had also studied at the Law School and was working for the Committee of Responsibility, which arranged to bring children who were napalm victims or had other war injuries to the United States for treatment and rehabilitation.[5] It turned out that Tom Miller, my Yale classmate, had quit his lucrative job in corporate law, and had also become involved with a program related to the Committee on Responsibility. He helped found Children’s Medical Relief International, which sponsored a plastic surgery hospital in Vietnam that treated young war victims. The Committee of Responsibility was at the time bringing war victims to the United States. The U.S. government, embarrassed by this, helped fund the hospital in Vietnam, writes Miller[1] Tom met Tran Tuong Nhu, a friend of Mai’s with extensive family contacts on all sides of the political divide. They were eventually married, and became another Vietnamese-American couple brought together by the war. I think Tom and Nhu were able to ignore any negative responses when they appeared in public, but Hoa and Tom were sensitive to the constraints of being a mixed couple in Vietnam, as were Mai and me. “Tom and Hoa couldn’t travel together, or even go out together much, because the Vietnamese, particularly the youth, had a fixed idea about young Vietnamese women who went with Americans.”[6]

Because my focus on the Viet Cong and the progress of the war kept my attention on those things, I was not well informed about either Vietnamese domestic politics and things like the Third Force, and civilian war victims. Tom and Hoa Fox, and Tom and Nhu Miller were thus able to offer us important insights which we might otherwise not have been exposed to. Tom Fox, however, was in a very sensitive position because of his close connections with the Third Force. The Saigon government was suspicious of these contacts but so, it turned out, was the revolutionary side. A profile of Tom writes “The Foxes were not planning to leave, but a dangerous situation grew more dangerous. Hoa was pregnant. One evening when Tom was away, a close Vietnamese friend, a progressive Catholic, part of a Vietcong cluster, went to see Hoa one evening. Said Fox, ‘He told her that the communist cluster he belonged to planned to either kidnap or kill me because for some reason they believed I was CIA. I’d never had any connection with the government, my reporting was always very antiwar. My stories had the same theme: Students, people, all Vietnamese were getting screwed.’Hoa asked the young man to return when Tom came back. He did. Fox asked the Vietnamese to tell the cluster if they would give him two weeks, he and Hoa would leave the country.” “I was targeted,” Tom told an interviewer. “You can’t say, ‘Where do I hide?’ I was just too vulnerable.” The bargain was sealed. They flew to the United States in December 1972 “during the U.S. Christmas bombing of Hanoi.” They went to his parents’ home. “I was unemployed, no job prospects, a pregnant wife, no money and in Detroit.”[7]

[1] Gloria Emerson, Thieu’s Foes Trying to United To Defeat Him,” New York Times, September 24, 1971.

[2] Gloria Emerson, Thieu’s Foes Trying to United To Defeat Him,” New York Times, September 24, 1971.

[3] Arthur Jones, “Tom Fox’s path from Vietnam to NCR,” http://natcath.org/NCR_Online/archives2/2005a/012105/012105h.php

[4]“Miss To Kim Hoa Bride of T.C. Fox,” The New York Times, January 17, 1971.

[6] Arthur Jones, “Tom Fox’s path from Vietnam to NCR,” http://natcath.org/NCR_Online/archives2/2005a/012105/012105h.php

[7] Arthur Jones, “Tom Fox’s path from Vietnam to NCR,” http://natcath.org/NCR_Online/archives2/2005a/012105/012105h.php

GVN Political Failure in the Countryside

A major reason the GVN was unable to consolidate its military gains in places like Dinh Tuong was its inability to win over the rural base of support most likely to support it in opposing the Viet Cong. A striking illustration of this failure was the alienation of the village and district notables in Vinh Kim, which had been a center of political activism since the 1920s, and had produced a number of eminent people who had become nationally known. Through Hai Nien, a former Viet Minh who had earlier been the revolutionary leader of the village (which was also a district administrative center), I got to know the current GVN village chief and a variety of prominent local citizens, including the largest landowner in the area.