3

Sometime in 1964 a general in MACV headquarters developed a curiosity about why the Viet Cong were called “the Viet Cong.” I was assigned to find the answer. It took me many years to understand the full ramifications of this seemingly simple-minded question, but it turned out to be a good point of entry for the next phase of my life in Vietnam. In the spring of 1965 I joined the Rand Corporation and was put to work on their “Viet Cong Motivation and Morale Project.”

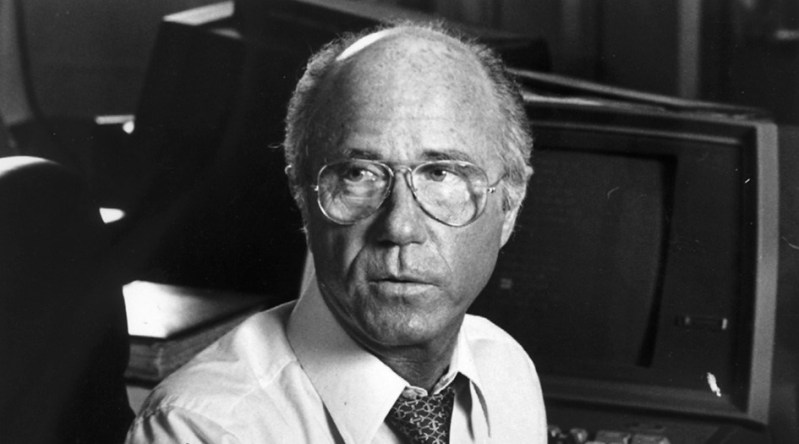

My first step in carrying out this MACV assignment was to find out who the leading American authority on the “Viet Cong” was. All trails led to Douglas Pike, an official of the United States Information Agency, soon to become the Joint United States Public Affairs Office (JUSPAO). I walked across the street from the Tax Building to his office on the second floor above the Abraham Lincoln Library (the target of the February 1965 demonstration). Despite his gruff, no-nonsense manner, Douglas Pike cordially received me, a military non-entity, and went out of his way to be helpful. I think he recognized a fellow fanatic with a single track focus on getting to the bottom of the question of who our enemy was and what made them tick.

These are two separable questions. The origin of the Rand Motivation and Morale Study which I joined in the spring of 1965 was a question posed by Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara in the spring of 1964, “What makes the Viet Cong tick?”2 As related in the previous chapter, McNamara’s top deputies did not like the answer they got from the first phase of the Rand study of Viet Cong Motivation and Morale. The Zasloff-Donnell briefing to McNamara’s deputy, John McNaughton, stressed the nationalist roots of the communist movement and “implied that the United States was facing a strong and dedicated enemy who ‘could only be defeated at enormous costs, if at all’”3

That was the preliminary answer to the question, “what makes the Viet Cong tick?” The seemingly more straightforward question, “who are the Viet Cong” proved more difficult to answer. Official US policy was based on the presumption that the southern insurgents were simply agents of an external force, the Hanoi government and the communist party that controlled it. As it turned out, the links between northern and southern revolutionaries were much more complex than the “aggression from the North” thesis implied.

Calling the insurgents “Viet Minh”, as many villagers in the South still did in the early 1960s, was unacceptable to the U.S. and its Saigon ally the Government of Vietnam (GVN), because it acknowledged the deep nationalist and anti-colonial roots of the movement. In addition, especially after a 1961 purge of older Viet Minh in favor of more energetic and malleable youth, the insurgents themselves avoided using the term. Calling them the “Liberation Forces,” as they called themselves was a political non-starter for those who did not want to be liberated. But even that was more acceptable than the National Liberation Front (NLF) after it was established in December 1960, because it was just that – a front – a façade intended to obscure the real power that created and manipulated it, the Communist Party. In a well meaning attempt to find a neutral term for interviewers questioning prisoners and defectors, the Rand Corporation decided to encourage the use of “the Front” as the most neutral term available. It did serve that purpose, but it was also confusing, because it was an unfamiliar and artificial-sounding term that interview subjects themselves never used, and it blurred the distinction between hard core insurgents and peripheral supporters.

Calling all the insurgents communists was inaccurate, because only the core leadership at each level belonged to the Party, and it obscured the wide support base of the insurgents who were active in the movement but not members of the Party. “Viet Cong” – Vietnamese communists, suffered the same defect. In the later years of the war, especially after the 1968 Tet Offensive, “Viet Cong” was used by the U.S. and GVN to refer to the Southern insurgents to distinguish them from the Northern forces infiltrated into the South from the mid 1960s on. Some tried to pin the label “terrorists” on the revolutionary forces but, despite the many acts of terrorism they committed, this did not catch on. The beleaguered peasantry found it prudent to employ a neutral term when speaking of the insurgents to the Government: “those gentlemen,” [mấy ổng] ” as in “those gentlemen passed through the village last night.” Sometimes it was further spelled out as “those Liberation gentlemen” [mấy ổng Giải Phóng].

One reason the U.S. government sponsored a “name your enemy” contest in 1958 was that they hoped to find a way to eliminate the “Viet” in “Viet Cong” (Vietnamese Communists) so as not to concede even that the insurgents in the South had a national identity. The model would have been the “communist bandit” (gong fei) term, devised by the Chinese Nationalist forces or “communist terrorists [CTs]” as the British termed the Malayan insurgents, also to stress the non-native character of the insurgents that they regarded as interlopers and troublemakers. The British in Malaya would have preferred to recycle “communist bandits” but eventually decided against it. One prominent book on the Malayan Emergency explained that “Throughout this book Communist guerrilla fighters are referred to as CTs, short for Communist Terrorists. At first they were officially labelled ‘bandits’ – until the British discovered that this word had unfortunate connotations. “Bandits’ had been the identical term used by the Japanese and Chiang Kai-shek to describe Communists; since neither of these powers had been successful, the use of ‘bandits’ by the British put them on a similar level in the eyes of the Malayan Chinese. The British therefore changed ‘bandit’ to ‘Communist Terrorist’ or CT. In order to make for easier reading, I have used the term throughout.”[1] For whatever reason, the entrants in the USIS “Name Your Enemy” contest were unable to improve on “Viet Cong,” and that term was deemed the winner by default.

Pike would soon write one of the landmark early books on the subject which he, reluctantly, termed “Vietcong: the Organization and Techniques of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam.”4 He wrote to his publisher “I suggest we name my book Viet Cong – not because the term is fully accurate (it is not) but because it will do what a title is supposed to do: tell the reader what the book is about.”5 Doug Pike was a wellspring of information on the subject of the Viet Cong, and he recognized in me a fellow seeker of the Grail, the deep understanding of the enemy America faced.

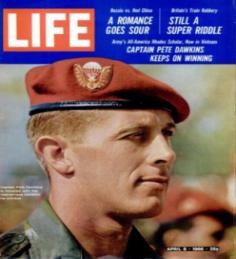

Douglas Pike

I started off from a position similar to his own; the view that the Viet Cong was essentially an organization machine that was cleverly and effectively deployed by a determined and ruthless leadership group, and that its success was due to its ability to steamroll the fragmented opposition to its rule. The “organization machine” image was reinforced by the nature of my work; like Douglas Pike I first encountered them as abstractions who appeared only in the form of written documents. Even when I started to do face to face interviews, it was with cadres who naturally emphasized the organizational dimension of insurgency. As noted below in this chapter, one critique of Pike’s view was that of an economist who concluded that “Mr Pike’s views derive from too much concentration on the evidence obtained from Communist cadres, themselves inevitably pre- occupied with organization as the main factor in Communist success in South Viet-Nam after 1960.”6 The complexity and massive scale of this written communication nexus was impressive. The subtitle of Pike’s book (Organization and Techniques of the National Liberation Front) reveals his general orientation toward understanding the revolutionary organization in the South.

By the time I summed up my work of the revolutionary movement in the Mekong Delta in 2003, I had come to reject the “organizational machine” view of the revolutionary movement. I also decided not to use the term Viet Cong, though I will do so in this memoir for the same reason Doug Pike used it in his book, because it is the term most familiar to most readers. But I will note the caveat here. In the Vietnamese War I advised prospective readers that “There are a number a terminological pitfalls in the study of this revolutionary movement. The most obvious is what to call the movement and the people in it. This is especially perplexing after 1960. Calling the movement and its members the ‘Viet Cong’ is more comprehensible to a general audience, but is also a pejorative term which was devised for psychological warfare purposes by the enemies of the revolution. It is sometimes used in a sarcastic way by the “Viet Cong” themselves in postwar revolutionary accounts, but given the origins and purpose of this term, it seems inappropriate for a scholarly study. An even more important drawback of this term is that it blurs the distinction between the more and less committed members of the revolutionary movement, and thus confuses the key issue of nature of the movement and the extent of its base of support. Nonetheless there are some occasions dictated by the context when the term the ‘Viet Cong’ is used in parenthesis to indicate the post-1954 revolutionary movement in South Vietnam. In the Rand project, interviewers were requested to use the term ‘National Liberation Front’ (NLF) or, simply, ‘the Front.’ This had its drawbacks as well. Sometimes when it was important to make a distinction between the NLF and the Communist Party, for example, the respondent would take the cue from the interviewer and say ‘Front’ while meaning ‘Party.’”8

Doug Pike had a competitor for the title of “leading U.S. government specialist on Vietnam.” That was the CIA’s George Carver, who evidently preferred to study his subject from a distance, in the secure confines of the agency’s headquarters in Virginia. Thus it is not surprising that Carver saw the Viet Cong not only as a machine, but as “faceless.” In an article in Foreign Affairs, Carver wrote “Though the outlines of the Viet Cong’s organizational structure are fairly well known, the identities of its leaders are not. They are faceless men, veteran Communist revolutionaries who have made a lifetime practice of masking their identities under various aliases and noms de guerre and who take particular pains to stay hidden in the background to support the political fiction that the insurgency is directed by the N.L.F. and the Front’s ostensible officers.” Carver added “It is fairly easy to devise an organizational structure capable of lending verisimilitude to a political fiction, doubly so if one is trying to deceive a foreign audience unversed in local political affairs. Fleshing this structure out with live, known individuals to occupy posts of public prominence is considerably more difficult.” 9

Of course, it is likely that Carver had a déformation professionelle a proclivity to view things from the vantage of one’s own life’s work and training. Or, as the Vietnamese saying goes suy bụng ta ra bụng ngừơi – to project your own thoughts and motives onto others. To be “faceless” is the CIA ideal – indeed Carver hid his CIA identity in his Foreign Affairs article and presented himself as merely a random interested observer. The professional environment from which Carver operated is illustrated by a recent article on the current CIA director. “The desire to appear unremarkable tracks with Haspel’s past as a CIA operative. As Jenn Williams, the deputy foreign and national security editor at Vox, put it on Vox’s Today, Explained podcast: “[Haspel] has kind of mousy brown hair. She looks like she could be your sixth grader’s principal. She looks just like a random lady who passes on the street and whose face you would forget within a minute. But that’s a good thing — if you’re in clandestine operations, you do not want people to know your face. You want to blend in.”10

The “faceless Viet Cong” label caught on in the American press. In part it was due to a real ignorance on the part of the CIA and other intelligence sources the press had to rely on for information about the Viet Cong, and in part it was a reaction the frustrations of being unable to personalize a complex story. The only two Vietnamese communist names an American consumer of the news was likely to recognize were Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap. Postwar scholarship has generally concluded that both Giap and Ho Chi Minh had been largely sidelined in the Hanoi power structure by the early and mid-1960s. But, lacking a better alternative at the time, many journalists continued to attribute all policies, strategies, and decision to these two men, inevitably reinforcing the view that the southern Viet Cong were mere puppets of Hanoi and that everything that happened on the ground in the south was a result of decision made at the top in the north.

Moreover the idea that whatever the Viet Cong did in South Vietnam was attributable to the decisions of top leaders in Hanoi obscured the reality that most of what happened was the outcome of a vast social movement whose significant daily actions were the result of a complex interplay of local factors that played out within the parameters of general Party policies. An obvious illustration is the attack on the airfield at Pleiku in February 1965 which led to the massive intervention of American troops.

Robert McNamara wrote that in February 1965 “there was little doubt in Washington that Hanoi had ordered the attack in Pleiku specifically to send a signal of its own to the United States while the Bundy team [National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy] was visiting Saigon.” In Washington’s view the incident meant that “Hanoi did indeed ‘seek a wider war’ via attacks such as were carried out at Pleiku.” At a conference in Hanoi long after the end of the war, McNamara discovered that the Pleiku attack was ordered by local revolutionary commanders “who had no idea that Bundy was in Saigon or that [Soviet Premier] Kosygin was in Hanoi… [and] were unaware that U.S. personnel were present at the time of the attack.! In other words, the Pleiku attack was not targeted at Americans, was not ordered by Hanoi, and was not designed by Hanoi to send a signal of any kind to anybody.”[2] One of the factors which reinforced the idea that the leaders of the insurgency were “faceless” was the impulse to attribute every action and outrage to an omniscient and all-powerful decision maker, who pressed a button and made things happen – thus the attraction of recognizable figures like Vo Nguyen Giap to American officials and the press.

More informed journalists, like Stanley Karnow (who later wrote one of the classic journalistic accounts of the Vietnam War and helped produce the first Public Television documentary on the subject), were well aware of limitations of their knowledge about the inner workings of the communist leadership in the South, and quite naturally ascribed this to the “faceless” nature of the Viet Cong. A column which Karnow wrote in early 1965 on this subject is a representative example of this view. Typically, the syndicated column was published under the heading “Viet Cong Terrorism” – certainly not a title chosen by Karnow. The combination of “terror” and “faceless” did strengthen the impression that the violence of the Viet Cong was sheer unreasoning evil, unrelated to any larger political purpose.12

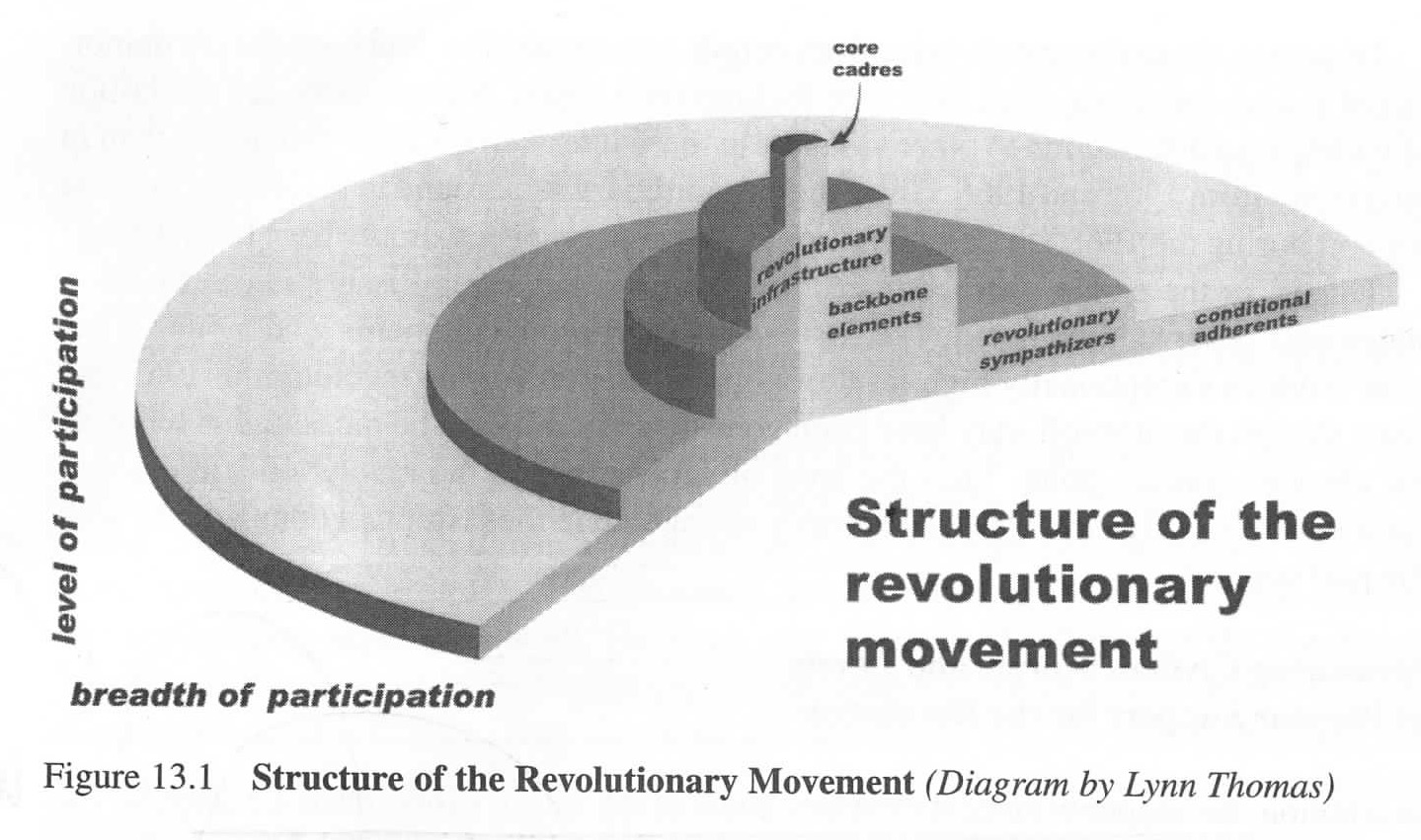

Karnow explained to his readers that “…of an estimated 300,000 Viet Cong activists, only some 40,000 belong to hard core military units. The rest of the Viet Cong’s ranks range from senior Communist political commissars to part-time guerrillas, tax collectors, doctors, spies, messengers, and even traveling minstrels used for propaganda programs or recruiting campaigns. Though nicknamed Viet Cong – which means ‘Communist Vietnamese’ – the movement is formally called the ‘National Liberation Front.’”13

Karnow noted that the real ‘revolutionary base” was in North Vietnam and, as did most journalists of the period, singled out General Vo Nguyen Giap, who was credited as the chief strategist of the battle of Dien Bien Phu as the most recognizable figure in the communist leadership. “Inside South Viet Nam itself,” Karnow observed, “the movement is ostensibly directed by a central committee of 54 ‘representative’ Vietnamese: peasants, workers, professionals, females, and among others, a Seventh Day Adventist minister. But the Viet Cong’s real chiefs are intriguingly faceless.” To illustrate the point, Karnow cited the uncertainty about the real identity of the figure that American intelligence had concluded was the top Viet Cong military commander in the South, known by his pseudonym Trần Nam Trung. “The movement’s military commander, for example, is believed to be a general called Tran Nam Trung, whose alias, Bay Quang signifies that he was the sixth son in the family. Other Viet Cong officers are not only mysteries to outside observers, but even to their own comrades.”14

In the spirit of responding to the question, “who were the Viet Cong” in the light of what the Vietnamese Communist Party has subsequently revealed about the identities of the once “faceless” southern Viet Cong leadership, I excerpt a condensed and paraphrased current official (2019) biography of Trần Nam Trung. So little was known about Trung by American intelligence in the early years of the war that the name was thought by some to be a fictitious placeholder pseudonym for whoever happened to be in command of the Viet Cong forces in the South at any given time. “COSVN goes to great efforts to keep secret the real names and functions of its members, and most officials have aliases. A notable example is the Viet Cong military commander, Tran Nam Trung, listed on the National Liberation Front charts as NLF Presidium member and Chairman of the NLF’s Military Affairs Committee. Tran Nam Trung does not exist as an individual; the name goes with the job, and a number of individuals, usually North Vietnamese Army (NVA) general officers, have variously occupied that position/name.”[3] Some analysts thought Tran Nam Trung was a pseudonym of General Trần Văn Trà.15

Trung’s biography illustrates one of the problems in putting a “face” on the Viet Cong – the widespread use of ever-changing secret names, pseudonyms, and informal names. His real name was Trần Khuy, born on January 6, 1912, in Đức Thạnh village, Mộ Đức, district, Quảng Ngãi province. He joined what became the Indochinese Communist Party in 1931. In 1944 he adopted the secret name of Trần Lương and joined forces with some key figures of the central Vietnam revolutionary movement, who later became senior leaders, such as Trần Quý Hai, Nguyễn Đôn, and Phạm Kiệt.

In 1955 Trần Nam Trung was elected a probationary member of the Party Central Committee, based in Hanoi, and put in charge of Party activities in southern central Vietnam. He returned to the north to report on the situation in that region in 1960 and was elected as a full member of the Party Central Committee at the Third Party Congress. Upon his return to the south after the Party Congress, he adopted yet another secret name Trần Nam Trung [which was the name that came to the attention of American intelligence] with the informal name used among his intimates, Hai Hậu. He was the political commissar of the group returning from Hanoi in May 1961 to again take charge in lower central Vietnam. This group was led by his superior Trần Văn Quang, an even more important leadership figure who remained virtually unknown to American intelligence until the Easter Offensive of 1972.16 Quang later became a news item in 1993 when a document, almost certainly fabricated, was widely cited as evidence that Hanoi had not given a full accounting of the American POWs it had held.17 Trần Nam Trung’s status was later made public when he was announced as the member of the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN) the leading Party organization in the South as the member in charge of military affairs. In June 1969 he was given a public face as the Minister of Defense in the newly established Provisional Government of South Vietnam.18

General Trần Nam Trung aka Hai Hậu

A “faceless” Viet Cong military leader in South Vietnam

Of course I would have been thrilled to have known all this information about the secretive top leaders of the Viet Cong in the South in real time when I was pursuing the answer to the question “who are the Viet Cong.” I had no idea who these people were or what they looked like when I started out with Rand. But even if I had, it wouldn’t have been particularly helpful in understanding the specific segment of the movement I would be studying in the upper Mekong Delta, as Trần Nam Trung’s authority was largely in southern Central Vietnam.

In fact, the command of Viet Cong forces in the South had been split into two commands, one for the center and one for the rest of southern Vietnam including the Mekong Delta. The Central Vietnam commander in Interzone V, later renamed Region 5, reported directly to the Central Military Commission in Hanoi, and the “Southern Region Command” (Tư Lệnh Miền), which covered everything south of Region 5, reported to COSVN. A U.S. Army history states that six months after the establishment of COSVN in January 1961, with the authority to direct “all the Viet Cong guerrillas and main force units,” “Communist Party leaders in Hanoi would split COSVN’s responsibilities by establishing a new administrative entity, Region 5 [the former Interzone 5]. Reporting directly to Hanoi, Region 5 would manage enemy military efforts in the northernmost portions of South Vietnam. Hanoi called the military headquarters under Region 5 the B1 Front and the military headquarters under COSVN the B2 Front .”19 It is not surprising, therefore, that there was confusion among U.S. analysts about who was in charge in the South, because the command was split into two separate hierarchies.

The truly faceless leaders were at the all-important regional level, supervising the provinces in their jurisdiction. For central Vietnam it was Region 5, the domain of Trần Nam Trung. His counterpart in charge of the rest of South Vietnam (B2) was Trần Văn Trà. But for purposes of my research in My Tho, the key leader was Nguyễn Minh Đường, known as Sáu Đường, the Party Secretary for Region 8, or the provinces of the central Mekong Delta. In my quest to find the Wizard of Oz, I was peeking behind the wrong curtain in looking for the traces of Trần Nam Trung, or even the more visible Trần Văn Trà, who I met long after the war and who had once operated in My Tho. Trà does play a significant role in my book The Vietnamese War, though I was only faintly aware of him at the time I was doing the actual research.

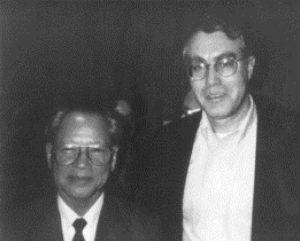

DE and Trần Văn Trà in New York, circa 1990.

For my purposes the real Wizard who was highly placed and powerful enough and yet close enough to the local realities to have a decisive impact on the way events played out on a weekly and monthly basis in places like Dinh Tuong was Sáu Đường, who was placed at the key intersection where grand revolutionary plans met hard reality. The Tet Offensive is a good illustration. Trần Độ was the deputy political commander in the southern provinces (B2] at the time. (I later met and interviewed him in Hanoi in 1982, when he had become the Minister of Culture and, still later, he became one of the highest level dissidents to ever break with the Vietnamese Communist Party). Trần Độ wrote, “I still remember that after phase 1, on the occasion of COSVN sending me down to where Tám Phương was [the provinces of the Central Mekong Delta where Tám Phương was the military commander], I met Sáu Đường, who at the time was the Party secretary of the region, and got into an argument with him. Now, thinking back on it, I believe I was stupid. Sáu Đường raised the question of how we could continue the attack in such a way that we could maintain a legal position for the people [e.g. not blow the cover of secret sympathizers living in Saigon-controlled areas by having them engage in overt activities]. But at the time there was a mind set of a ‘once-and-for-all attack’ [đánh dứt điểm] and bringing power into the hands of the people, so I wasn’t pleased to hear this man talk about maintaining a legal position [thấy ông này nói đến vấn đề giữ thế hợp pháp, xem ra không xuôi tai], so I argued with him that this was the moment to rise up and seize power, and that anyone who was opposed would be brought before a court and tried with no messing around. Why still talk about maintaining a legal position?”20

Despite this angry and ominous threat by the powerful General Trần Độ, the region Party secretary argued back. As the Northerner Trần Độ recalled, Sáu Đường told him, “No way, brother! We have been here a long time, and we see that as a matter of history, an uprising is not that easy. If we fight this battle, we also have to consider the possibility that the situation will not develop favorably, that the enemy will counterattack. Then what do we do? If they come back, how will the people [e.g., revolutionary supporters and activists] live? So there is no way we can’t think about the legal status of the people.” Trần Độ writes that, “listening to him put it that way, I had to admit that he was right.”21

It was only long after the war, when I came across his memoirs and was able to fill in the absolutely vital perspective of Sáu Đường, that many of the pieces of the Viet Cong puzzle in the central Mekong Delta began to emerge in a discernible pattern. During the time of the research I barely knew who he was since he was scarcely mentioned in the interviews and knew next to nothing about the rest of the Region 8 leadership. In fact it was the post-hoc memoirs and Party histories that finally began to flesh out the picture that I had only dimly understood at the time I was doing the Rand interviews.

Nguyễn Minh Đường, Party leader of Region 8, which was comprised of the provinces of the central Mekong Delta including Dinh Tuong (My Tho). On Ho Chi Minh trail to Hanoi for a series of Politburo meetings following the 1973 Paris Accords

Nguyễn Văn Linh top Party leader in the South in center, fourth from right. Third from right is Nguyễn Minh Đường

Sáu Đường and family in My Tho 2000 Photo DE

Even in my ignorance, I began to discover what I didn’t know, which was the beginning of wisdom in a venture such as finding the answer to the question, “who are the Viet Cong?” My first years examining the Viet Cong movement for Rand revealed that the image of the “faceless Viet Cong” was in some respects true, but quite misleading. Any movement which had been forced to operate as a clandestine opposition movement against an established authority trying to eliminate it from its inception will inevitably develop a cult of secrecy simply out of self preservation. When I started my research in Dinh Tuong province, I quickly discovered that the marginal hamlet and village members of the insurgency had only a hazy grasp of the leadership at higher levels; the district, province, and region – to say nothing of the secretive top leadership of the movement in the South – the Central Office of South Vietnam or COSVN.

Photo of Nguyễn Chí Công (Chín Công, Chín Ốm, Chín Dư) in a base area. The leader of the Party organization in My Tho from 1962 to 1968, he often appeared as a shadowy figure in interviews with the Party rank and file in the province, and few had direct contact with him. On right is a studio portrait of Nguyễn Chí Công

In addition, Carver was correct in asserting that the purported leaders of the insurgency who were the public face of the movement, the top officials of the National Liberation Front were non-entities who had no real power or influence in the movement,

It is also possible that the image of the “faceless” Viet Cong was more a commentary on the gaps in CIA knowledge of the enemy than the invisibility of the cadres to the people they worked with. In his first trip to Vietnam in 1965 Kissinger queried the CIA on the nature and identity of the enemy. “Who exactly were the Vietcong? inquired Kissinger innocently. ‘They said they knew the Vietcong at the province level, but they did not know the names of the Vietcong at the district and fighting level and that in many cases they know only code names.’”22 It turned out that the reality was, the further down the hierarchy the more was known about the individuals active in the “Viet Cong.” In our Rand study, we had a great deal of information about “fighting level” insurgents, and even some information about key district cadres, but knew very little about the province level, and still less about leaders higher up than that.

But there is a contradiction between the two prominent ways in which the U.S. government depicted its enemy in Vietnam. The “Organization Machine” implied that all members, including the leaders, were simply cogs in the machine, and that distinctive personal qualities such as charisma were irrelevant. In a way, a faceless group would be the inevitable product of such a system and an indicator of its strength, rather than a weakness, since it would not be dependent on the individual qualities of its members, because they had all been poured into the same mold. If the cogs in the machine were all merely interchangeable parts, programs aimed at crippling the insurgency like the Phoenix program, would be much less effective in “degrading” its effectiveness. It was the idea that the organization mattered more than the people in it that the Khmer Rouge were trying to project in insisting that all their actions and orders were undertaken in the name of Angkar – The Organization.

.

Wizards of Armageddon

Mai had already gone to work for Rand as an interviewer in late 1964, and I met the original Rand team, Joe Zasloff, John Donnell and Guy Pauker a number of times in that period. It was Guy Pauker who made the original overture to me about joining Rand. My knowledge of the Vietnamese language and experience in translating Viet Cong documents were certain to be useful to Rand in its study of Viet Cong Motivation and Morale. Moreover, I had two years of graduate study which provided me with additional credentials for this think tank.

On top of that, Guy Pauker had studied at Harvard under my father, who had also been instrumental in obtaining an appointment for Pauker as instructor in the Government Department. As I found out much later, they had corresponded extensively about Pauker’s first trip to Vietnam. In the summer of 1956 Pauker wrote my father, William Yandell Elliott (WYE), on his impressions from an extended stay in South Vietnam. “Dear Bill: I have just reached half-time in my Vietnamese assignments and begin to have some feel for the local situation. I gave fifteen two hour lectures in French, with half the time devoted to questions. I spoke to members and especially cadres of the two organizations supporting Diem, the Mouvement de la Revolution Nationale and the Rassemblement des Citoyens. I had a three hour session with Diem and long talks with cabinet members their political advisors and knowledgeable Americans including our very attractive ambassador Frederick Reinhardt.”23

Pauker informed WYE that he would “now spend some two weeks in the provinces lecturing and talking to people. Some of the lectures are to civil servants, others to army officers, most of them to political groups. The main topic is constitutional government. This country has really achieved a political miracle. A basis for a stable government has been created. The population is certainly more confident in the government’s power to protect it than at any time in the recent past. As a result, while there is still a very serious problem created by the underground Viet Minh in South Viet Nam, I have the impression that they are over the hump. July 20 passed without incidents, and Ngo Dinh Ngu [sic – this innocent bowderlization of the given name of Ngo Dinh Nhu rendered it “Ngo Dinh Idiot”], the President’s brother, told me the other evening that it was due to effective security measures which thwarted Communist plans to organize demonstrations in Saigon, not in Communist ‘reasonableness,’”24

Pauker was under no illusions about the repressiveness of the Diem regime, but considered these traits necessary, given the challenges from the communists. “But the economic situation would be hopeless without our aid and countering Communist propaganda and subversive activities takes sometimes itself quasi-totalitarian forms. So there is much to be done, but Viet Nam has come a very long way since Geneva.”25 WYE duly passed along Pauker’s observations to the State Department and to Eisenhower’s national security advisor William Jackson in an attempt to build more support for Diem among skeptical Eisenhower officials in the State Department and the NSC (“You know how difficult the audience is there,” WYE wrote Pauker).26

Pauker, who had personally experienced the precariousness of life as a Jewish outcast in Romania during its Nazi occupation, and then persecution by the communists when they consolidated their grip on Romania following the end of World War II, escaping across three borders on foot and ending up in exile in the United States, became an object of derision in the academic community and even among his Rand Corporation colleagues for his malleable views. He was pessimistic about U.S. prospects in the Vietnam War but switched to supporting government policy. After expressing initial pessimism about the wisdom of American involvement in Vietnam and providing a trenchant supporting analysis, Pauker publicly defended the Johnson administration’s policy in the 1965 escalation. Hearing that there would be a televised debate between McGeorge Bundy and anti-war critics in the summer of 1965 and that Pauker would participate, “In a chorus, everyone present asked, ‘On which side?’”27 Later he was widely suspected of turning over a confidential study of the 1965 coup in Indonesia, circulated only to a select group of American Indonesian specialists because of its explosive content, to the generals who were accused by the study of provoking the coup, to the considerable professional detriment to one of the authors of this study, Ben Anderson, who was on my thesis committee at Cornell.28

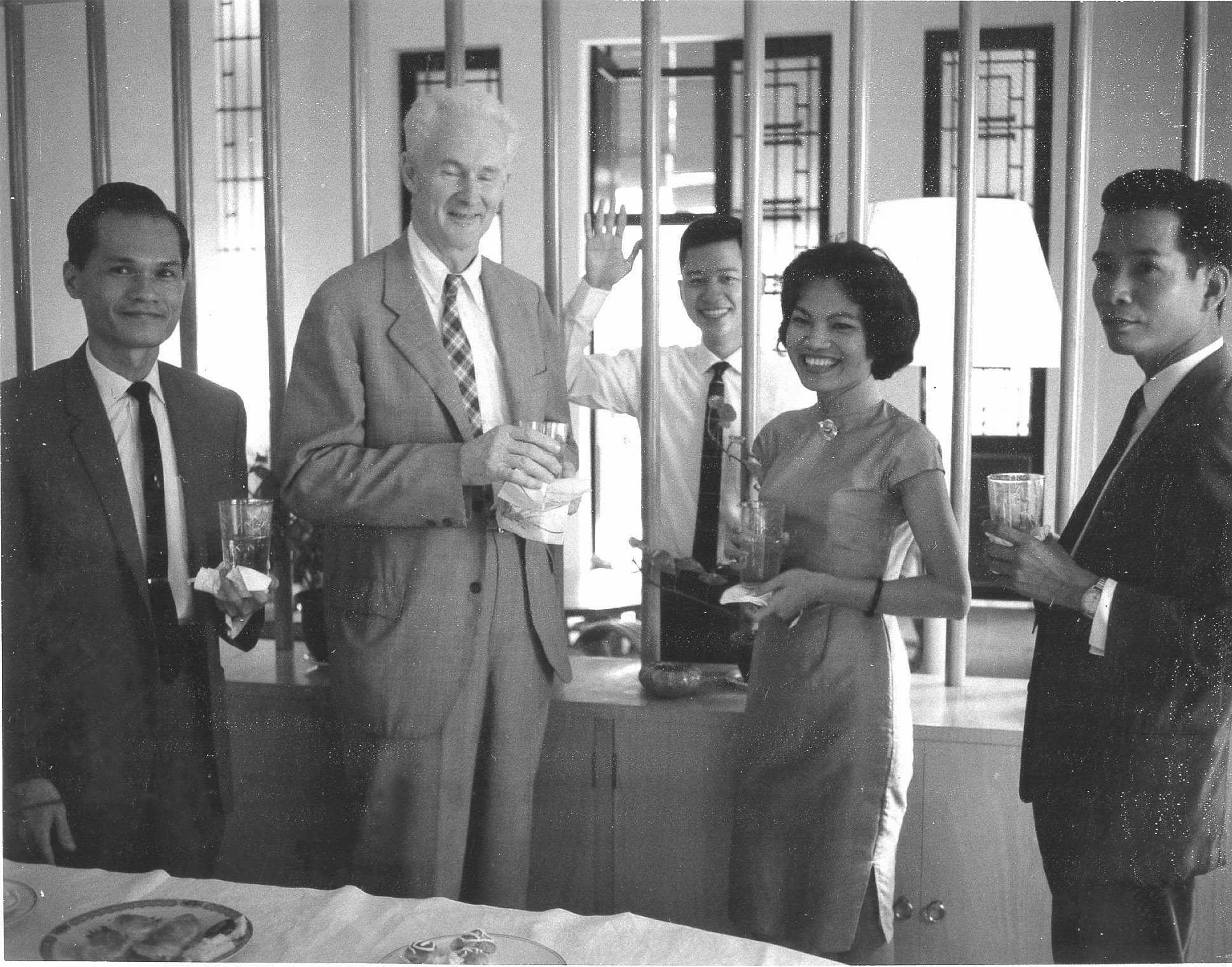

Guy Pauker and DE 1964

Given this relationship between my father and Pauker, as well as my own credentials, my path to Rand was probably over determined. In addition, my father had extensive contacts with Charles A. “Chuck” Thomson throughout the 1950s, when Thomson was an official of the Rockefeller Brothers Study. By 1963, Thomson had moved to Rand. In her history of Rand in Vietnam, Mai Elliott writes “Chuck Thomson was then the administrative officer of the Social Science Department, focusing on problems of budgeting, reporting, and personnel, but also working on issues of command and control, and U.S. civil defense. In Saigon, as Leon Goure’s deputy. Thomson helped with the development of the [interview] questionnaire and with staff issues, and would co-author some of the reports. Whenever Goure returned to the United States, Thomson would fill in as project manager.” Tony Russo, a young analyst who joined the Saigon project, described Thomson as “a craggy, snow-haired man in his 50s” with “the air of a stern schoolmaster.”29

Chuck Thomson at Rand Saigon, circa 1965

My first encounter with the new regime that would replace Zasloff, Donnell and Pauker, was with the newly appointed project director, Leon Goure. After processing out of the army at Travis Air Force Base, I went to Santa Monica to sign on with Rand. I was there only for a few days – long enough to get a feel for the structured informality of the place. Because of a surfeit of PhDs, Rand had adopted a policy of first-name informality, and formal titles “Dr. This and Dr. That,” were frowned upon. Everyone called the President Frank Collbohm “Frank” and security guards and Rand superstars were all on a first name basis. For a place which had the reputation of nurturing the “Wizards of Armageddon,” and providing a platform for “Dr. Strangelove,” Rand had a disarmingly mellow and breezy ambiance. The building had the institutional and architectural profile of a retirement home, perfectly situated by one of Southern California’s best beaches.

Rand Corporation headquarters Santa Monica

I didn’t rub elbows with many Wizards of Armageddon, but spent most of my time with the friendly and efficient administrative assistant of the Social Science Department, Rita McDermott. For me she was the face of Rand, which I found would be a supportive environment to pursue my quest of understanding America’s enemy in Vietnam. It seemed like an unbelievable stroke of luck to find a platform which would provide the necessary entrée and material support to pursue this goal.

After a short stay in Santa Monica, I joined Leon Goure, the newly appointed project director of Rand’s Motivation and Morale Program in Saigon, for the return trip to Vietnam. I was familiar with the previous iteration of this program under Zasloff and Donnell, but did not yet know that Goure’s appointment to succeed them marked a major shift of orientation from the original goal of finding out “What Makes the Viet Cong Tick.” This story is expertly told by Mai Elliott in her book Rand in Southeast Asia, and I will not repeat it here.

Leon and I stopped over in Hawaii to attend a briefing on Vietnam at the headquarters of the Commander in Chief, Pacific (CINCPAC). Leon was appalled that I had not bought anything for Mai, and shamed me into buying a gift at the airport. Since I was then, as well as now, a jerk who ostentatiously rejected commercial conventions like greeting cards and Valentine’s Day observance, I only partly bowed to Leon’s pressure. I bought a cheap key chain on a rabbit’s foot to make the statement that I would not be dictated to by convention. Leon was even more appalled at this flouting of sentiment and good manners. Whatever his flaws, Leon was extremely thoughtful and considerate in human relations generally and, of course, courtly and a great gallant in his dealings with the opposite sex. He was, therefore, amazed to encounter someone as obtuse as me. Fortunately, Mai took it in stride and responded philosophically that it was the thought that counted. Not only did this “gift” not have great sentimental value, it was of little practical use since Vietnamese rarely carried keys around in those days (someone was always home so the doors were rarely locked, and very few had a motorized vehicle at the time).

At the CINCPAC briefing in Honolulu I was intrigued by the experience of watching the upper echelons of the system in I which I had been a remote appendage at the lowest levels of the chain, but it also made me aware the for all the trappings of power and the sense of being a privileged witness to the inner circles of government, that the briefers did not seem to be particularly insightful or well informed. CINCPAC seemed very distant from the realities of Vietnam, and I certainly did not sense any sense of desperation or urgency, even though we now know the situation was unraveling in Vietnam at a rate not fully understood even by Americans who were in the country. There were certainly no intimations that within a month Marines would be on their way to salvage the situation. But the fact that these briefings were being given in the rarified atmosphere of CINPAC, and were presumably passing on knowledge accessible only to the very powerful, gave the contents of their briefings an authority which was not warranted by its intrinsic merit. At the time, however, I accepted it on the grounds that it represented an informed view far about my pay grade. In my new civilian status, I was the equivalent of a GS-12, equivalent to Captain, according to my newly issued civilian ID card for MACV. It was a significant step up from Specialist 5th class.

Leon became a polarizing figure both inside and outside Rand, as Mai’s Rand book makes clear. Like many others, even among his critics, I found Leon charming and personable – something of a likeable scoundrel. We enjoyed a relaxing evening in Honolulu after the CINPAC conference, watching the show of the leading Hawaiian entertainer of the period, Don Ho, before continuing on the long flight to Saigon. On arrival, Leon and Chuck Thomson and I began to discuss how my talents could be put to best use.

I can no longer remember whether or not my first major interview done for Rand was specifically targeted to explore the subject of psychological warfare, or whether the interview subject was selected on the grounds that he was the highest-ranking defector then available for interview at the Cholon Chieu Hoi center, but the first interview I undertook was with a member of the Propaganda Section for the Saigon-Gia Dinh Special sector. Mai joined me on April 21 and again on April 23, 1965 to do an interview which, transcribed and typed totaled 60 pages. I will call the subject of the interview “D.”

“D” had joined the revolution in 1961 after being discharged from his job as a clerk typist in a district in the lower Mekong Delta because he did not have an elementary school diploma. He went to Saigon and opened a small shop making cabinets for radios. “In 1961, I met a VC cadre, a friend of mine, who propagandized me on the dictatorial nepotistic rule of Ngo Dinh Diem. He accused the Americans of being imperialists like the French. At that time I did not fully understand the question of the Americans being imperialists, but I could understand very well that Ngo Dinh Diem was maintaining a dictatorial family rule in South Vietnam and that Ngo-Tran [Ngo Dinh Diem, his brother Nhu and Nhu’s wife Tran Le Xuan] controlled the economy of the country and monopolized the market. They oppressed the people and I hated them. I therefore agreed to work for the Front. I joined the Front out of my personal grievances for having been discharged from my job by the GVN [Government of Vietnam].”30

I didn’t know it at the time, but his brief personal history was a tip-off to a major development in the evolution of the revolutionary movement, which escaped Rand, as well as U.S. and GVN intelligence at the time. Only in 1967 did I learn from Rand interviews in My Tho that in 1961, the year that “D” joined the revolution, there was a massive purge of former Resistance members ordered by Directive 137 from the Central Committee in Hanoi. The purpose was to “rectify” and purify the ranks of the Party and clear the way for an infusion of new members who would be younger, more obedient, and not compromised by any “mistakes” in their past.31

The first Rand study in 1964 had emphasized the continuity of the “Viet Cong” with the anti-French Resistance movement, the Viet Minh, and cited this as evidence of the deep nationalist roots of the revolutionary movement. In fact “D”’s case shows how complex this subject is. Although he joined the “Viet Cong” in 1961 as part of the new intake to replace purged members, he himself had been involved in the Viet Minh movement as a clerk typist for various District Finance-Economy sections in the southern Mekong Delta, before being dismissed by the Viet Minh for his irascible behavior in 1951. In 1952, increasing French military pressure on his village forced him to seek refuge in Saigon, where he could be anonymous and opt out of the war. Ironically, it was his dismissal from a similar clerk-typist position with the GVN that pushed him to join the Viet Cong. Because he had not been a Party member in his previous stint with the Viet Minh, but only a mere clerk, he was evidently allowed to start with a clean slate, but if I had known about Directive 137 when I interviewed him I might have spent more time on discovering how someone with such an initially sketchy grasp of the key ideological issues (he “did not fully understand the question of the Americans being imperialists”) when he was recruited. and a checkered past, had made his way to such an elevated political position, in the propaganda sphere, no less. This is an illustration how little I knew at the beginning of my Rand career. Only decades after the war was over was I able to reconstruct what the interviews were really telling me, and identify the questions that I had been too ignorant to ask at the time.

The interview with “D” went into laborious detail about the organizational structure of his unit, the Propaganda Section of the Saigon-Gia Dinh Party Committee, which was responsible for Saigon and its suburbs, and reported to COSVN, which directed the revolution in South Vietnam. These details were of interest to me, because I was still trying to flesh out the organizational structure of the Party in South Vietnam which I felt was the main source of strength for the revolutionary movement. What interested Chuck Thompson, however, was the elaborate detail in the interview about how revolutionary propaganda was devised at a high level, and “D”s scathing critique of GVN propaganda, as being irrelevant and unpersuasive to its target audience. It was probably Chuck Thomson who saw this as a fruitful avenue of research to complement the ongoing Motivation and Morale Study, which was in the process of being redirected from studying the strengths of the Viet Cong to finding their vulnerabilities and weaknesses.

Leon knew exactly what he wanted to accomplish, and plunged into a study of the effects of bombing on Viet Cong morale which he hoped would solidify the institutional position of the Air Force, not coincidentally the main defense sponsor and funder of the Rand Corporation. Ultimately Leon’s attempts to curry favor and advance himself backfired, and he was eventually eased out, and Rand’s reputation suffered badly by his manipulation of the interview data.32 Although Chuck Thomson co-authored many of Leon’s controversial reports and evidently had no problems with either the methods or conclusions, he sought alternative projects that he could work on without being under Leon’s shadow. Psychological warfare seemed to be a field which Leon had only a peripheral interest in (especially in how the terror of bombing could be exploited) but he left this subject largely to others while he focused on issues closer to the interests of his Air Force patrons. This left an opening for Chuck Thompson, who shopped my interview with “D” around town. It eventually morphed into the first Rand study, which I co-authored with Chuck, and which took a slightly different direction from the main Motivation and Morale study in focusing on low level civilian cadres and their vulnerabilities.

As Leon and Chuck looked around for a project to assign to me, the topics of “vulnerability” and “psywar” suggested themselves, because these were areas in which MACV generals did not claim any particular expertise. In addition, “psywar” seem innocuous in that it did not challenge anyone’s turf and, at the same time, seemed as though it could be marginally useful. So Leon presented MACV with a proposal to do a detailed study of these issues in a single province, in order to gain the depth of knowledge and continuity of understanding that was difficult in a country-wide study in which neither the interviewers nor the analysts gained a profound grasp of a specific area.

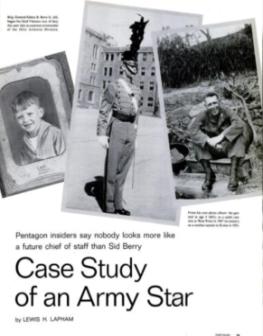

“In June 1965, General Westmoreland requested that the project be undertaken to uncover the vulnerabilities of the Viet Cong, as well as to determine the kinds of programs that should be formulated to exploit their weaknesses and ways to measure the effectiveness of such programs. Besides Westmoreland, General William E. DePuy, the operations chief for MACV, was also enthusiastic because he wanted an in-depth study that he hoped would yield information about the Viet Cong so that the military could fight them more effectively.” As noted in Mai’s book Steve Hosmer, another Rand analyst who played a prominent role in the Vietnam program during the mid-1960s, later said that in 1965 “General DePuy had not turned against counterinsurgency in favor of all-out conventional warfare against the enemy.”33

General William DePuy, Westmoreland’s operations officer

I recall a dinner at Rand’s villa at 176 Pasteur organized by Leon, during which I engaged in conversation with a rather diminutive and un-martial man in civilian clothes to whom I had not been introduced. Thinking him a civilian non-entity I was not, as I recall, particularly deferential to his opinions or to his status. It turns out that this was General DePuy [pronounced DePew], as I soon discovered. To his credit, DePuy did not flaunt or assert his rank, and listened politely to my opinions (though I can no longer recall the substance of the exchange).

It seems that Hosmer may have misread DePuy’s approach to the war in this early period. Neil Sheehan writes that “The Vietnam to which John Paul Vann returned in late March 1965 was a nation on the threshold of the most violent war in its history. At the beginning of the month, Lyndon Johnson had started Operation Rolling Thunder, the bombing campaign against Vietnam. Two U.S. Marine battalions, the first of many to follow, had landed at Danang to secure the airfield there as one of the staging bases for the bombing raids. At MACV headquarters in Saigon, William DePuy, then a brigadier general and Gen. William Westmoreland’s chief of operations, had taken the first step in planning that was to bring hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops into South Vietnam with artillery and armor and fleets of fighter-bombers for a new American war to destroy the Vietnamese Communists and their followers. “We are going to stomp them to death,” DePuy predicted.”34

Nonetheless, DePuy did not stand in the way of more nuanced approaches to dealing with the Viet Cong, nor did Westmoreland. “To conform to Westmoreland’s interest, Leon Goure defined the project’s objective as helping improve the ‘the Psychological Warfare effort in [Dinh Tuong] province.” Goure envisaged the project as an operation that would unfold in three stages. At the beginning, the focus would be on ‘uncovering vulnerabilities’ among the enemy military and civilian ranks. Afterward, psychological themes and appeals would be developed by the GVN, with advice from American officials to target these vulnerabilities. Finally, the effectiveness of these appeals would be measured through interviews.”35

It could be that the future direction of the My Tho project was not fully determined by Westmoreland’s request in June 1965 that it explore Viet Cong vulnerabilities and that I had a more proactive role in defining the parameters of a study that would be distinct from the Motivation and Morale project. Over a half century later I came across a letter written by Mai to my parents on July 23, 1965 in which she said “Dave has also written a letter to Richard G. Stilwell, MAC-V Chief of Staff, in which he exposed his ideas on the need to conduct research on VC organization. He’s still hoping that Rand would OK this project. I hope the project would get off the ground because this is something Dave is really interested in.”36 I can’t recall the origins of my personal contact with Stilwell (no relation to “Vinegar Joe”) but I met him several times. He knew my father and when we accidentally crossed paths at Tan Son Nhut inquired after his health. Stilwell had been a protégé of Westmoreland throughout his career. So it is possible that this letter had some impact and that Stilwell had some role in facilitating the orientation of the Dinh Tuong program toward the study of Viet Cong organization. In any case that was the focus that evolved.

Maj. General Richard G. Stilwell,

Chief of Staff, Military Assistance Command Vietnam 1965

Introduction to My Tho

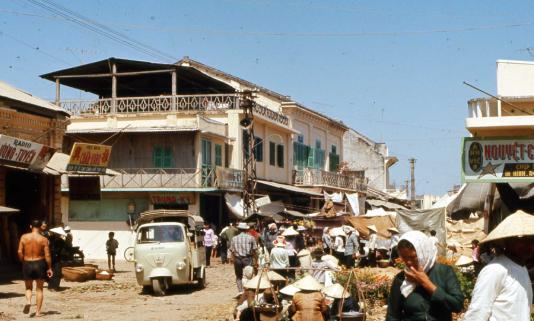

Aerial view of the town of My Tho and the upper branch of the Mekong River November 1967

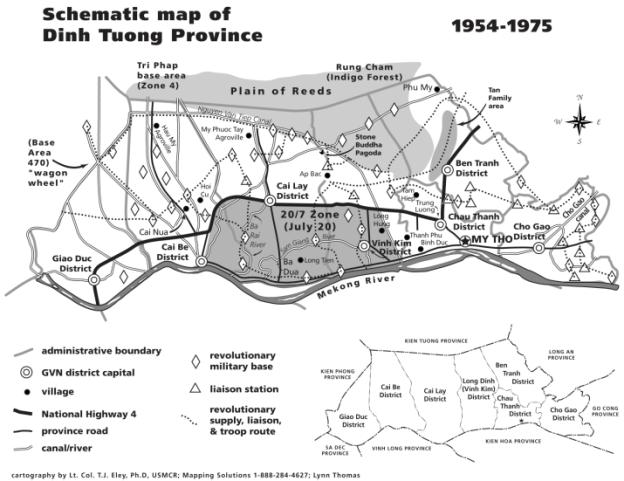

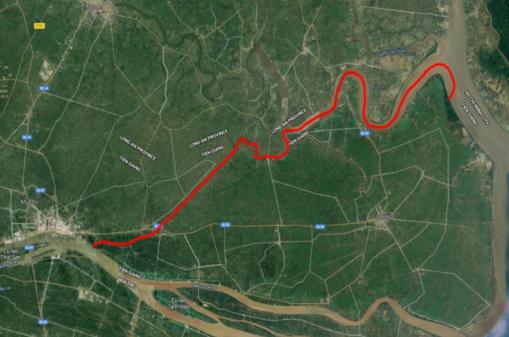

Dinh Tuong province was a large (population 500,000) and geographically important province that linked the lower provinces of the Mekong Delta to Saigon along the key land route of Highway 4. Most of the rice from the Delta that reached Saigon came along this route or the Cho Gao canal which connected the upper branch of the Mekong River to Saigon. It was the home of one of South Vietnam’s best divisions, the Seventh Division. The Viet Cong referred to Dinh Tuong province as My Tho province, which was also the name of its capital town, 35 miles south of Saigon.

The combination of strategic importance and accessibility – Highway 4 was generally secure during the daytime and, depending on traffic, the trip to My Tho could be done in less than two hours – made it an obvious choice as a test case for a detailed micro-study of the war. The first interviews of what became the “DT series” [Dinh Tuong] were actually done by a Saigon-based team within the framework of the ongoing Motivation and Morale Project. In June 1965 I was joined by my fellow graduate students at the University of Virginia, Nguyễn Mạnh Hùng and Tạ Văn Tài who had recently returned to Vietnam after finishing their PhDs, and were teaching at the National Institute of Administration. They agreed to temporarily help out as the program was just getting established.

About that time Mai and I decided to move to My Tho from Saigon. We had been working out of our house in Saigon since my arrival with Rand because the Rand village at 176 Pasteur was overcrowded.

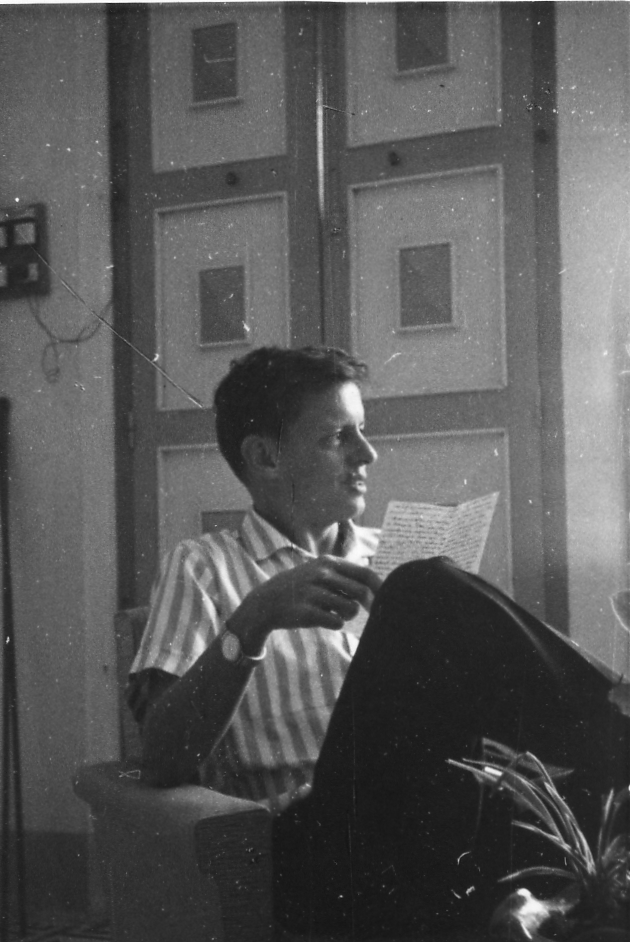

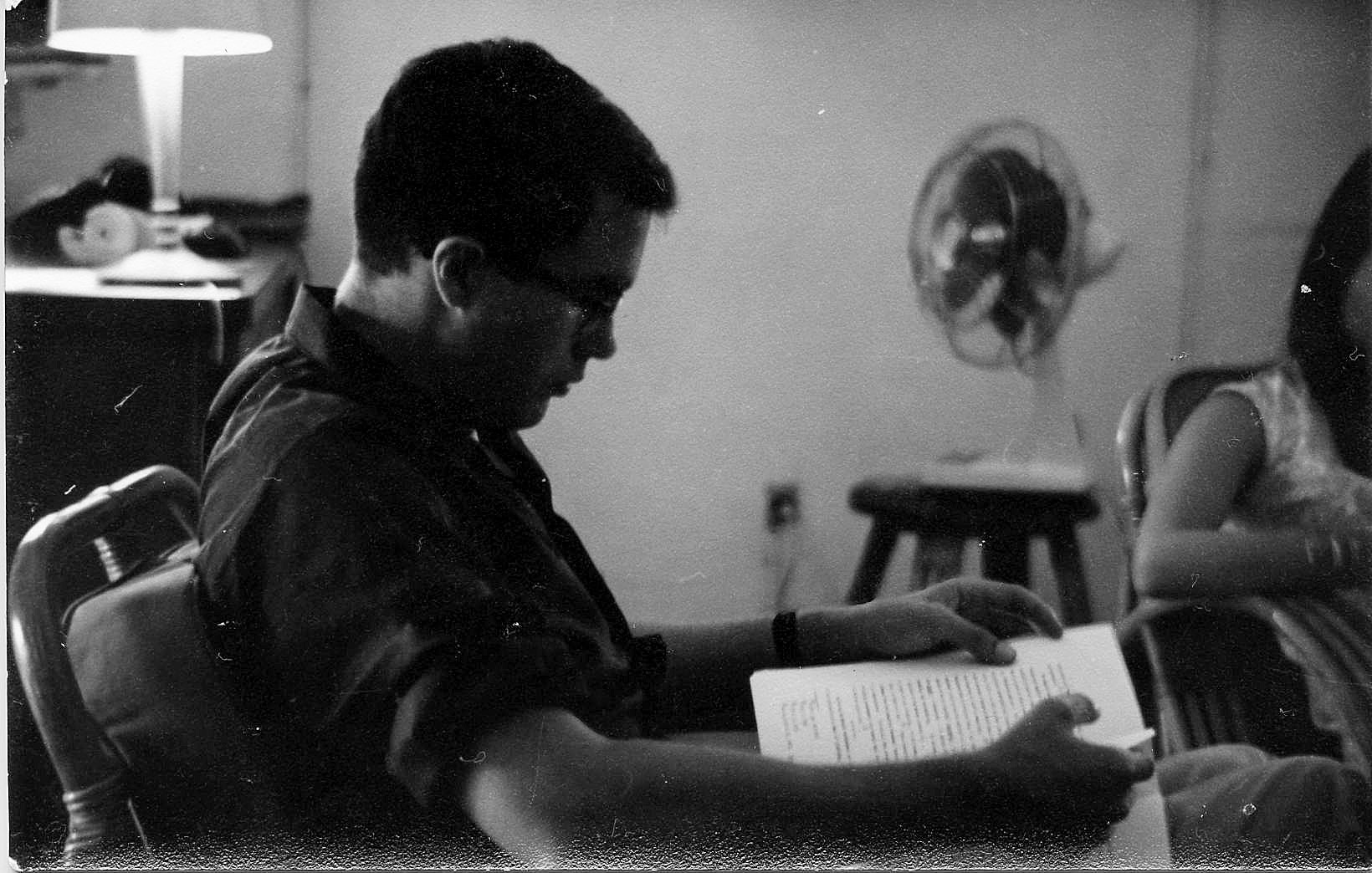

DE looks over manuscript in his home office at 223 Phan Thanh Gian in Saigon ca 1965

As more interviewers joined our team and the operation expanded we would have to expand our local presence in Dinh Tuong. Finally, Mai was concerned about my driving to My Tho on a weekly basis. Even though Highway 4 was generally secure during the daytime, the unexpected was always possible, as in the picture below of the junction just outside of the town of My Tho where Highway 4 turns west and bisects the central districts of Dinh Tuong province.

Flaming remains of a bus which had been mortared during the daytime at Trung Luong intersection near the town of My Tho, 1966.

So we rented a Citroen from Col. Phước, put all our worldly possessions (which were not many) in it, and drove down to My Tho where we had rented a house.

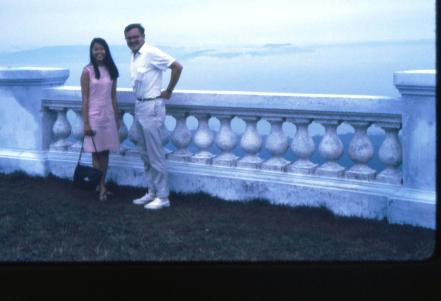

Mai and DE in rented Citroen, May 1966

Unfortunately the Citroen broke down halfway to My Tho, in the province of Long An. Although traffic was fairly heavy, the spot was deserted except for a brick kiln about 100 meters from the road. I was able to hitch a ride on the back of a passing motorbike, whose driver kindly transported me to the province town of Tan An. I went to the U.S. military advisors’ compound and explained the situation and asked for assistance. My wife is stranded in an exposed area, I said, and it is urgent that we get the car back in motion. Upon discovering that I was a civilian and that Mai was not an American, the advisors lost all interest and declined to help. This was a rare exception, since all my future dealings with American advisors were very positive and cordial. Fortunately I located a Vietnamese mechanic who drove me back to the stranded vehicle and fixed it. We then completed the trip to My Tho. Although we subsequently would often drive to Saigon for the weekend, we did not have further problems with the Citroen, which proved quite reliable. I later discovered that the brick kiln, the only nearby structure in sight where we had broken down, was a notorious Viet Cong sniper’s nest. I’m glad I didn’t know that at the time, because it would have left me in an impossible dilemma about leaving Mai to seek help.

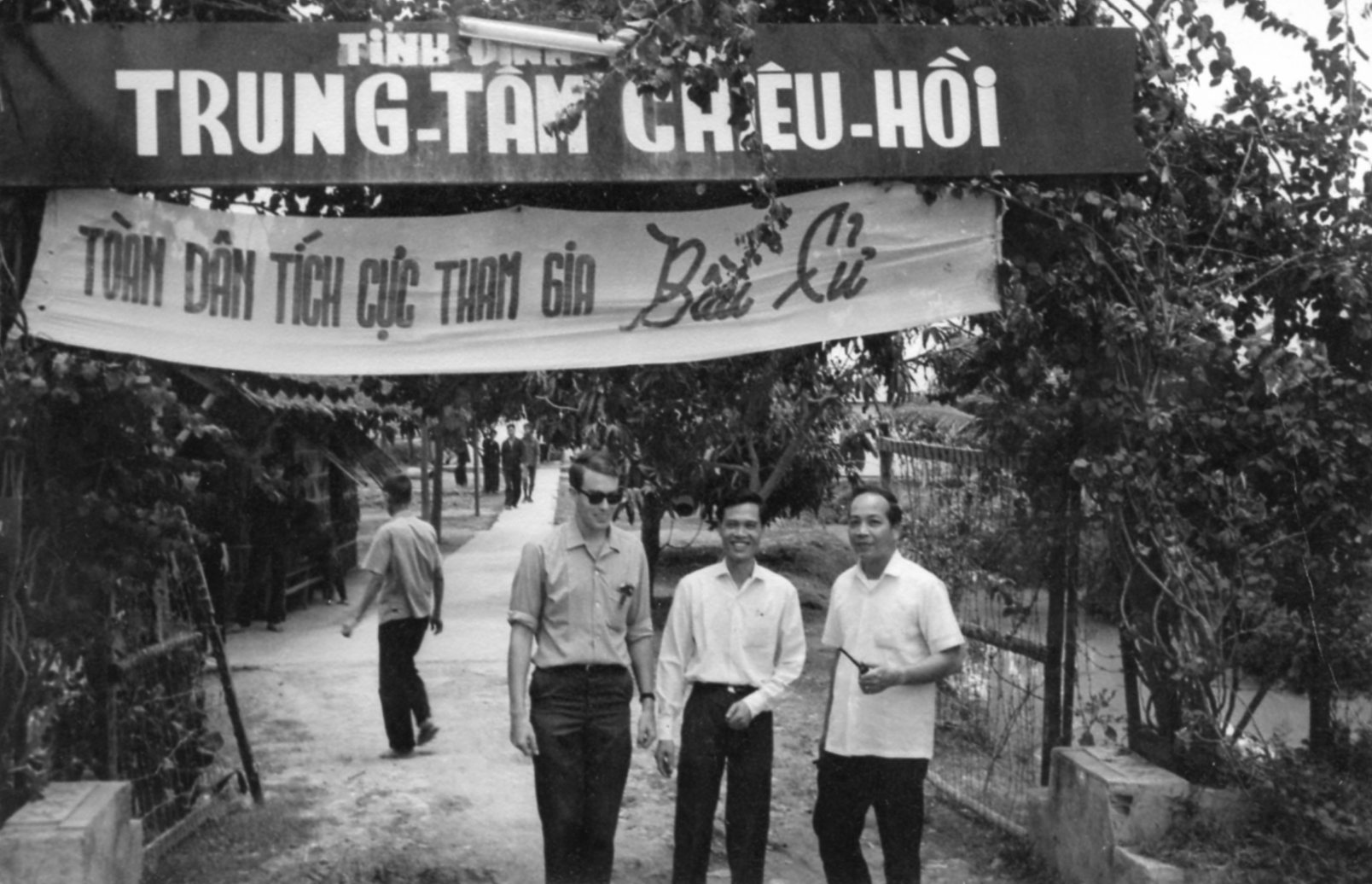

We moved into our new house at 27 Hung Vuong, the main boulevard of My Tho, and went to work immediately interviewing defectors the Dinh Tuong Chieu Hoi Center.

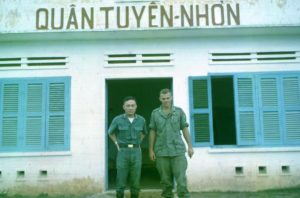

Dinh Tuong Province Chieu Hoi Center 1965: left to right DE, the director of the Center, and Đinh Xuân Cầu

In some ways these first encounters with former Viet Cong were as much an education for my grad school classmates Hung and Tai, who had volunteered to help out in order to get the project started, as for me. One of the “ralliers” (defectors) was induced to sing Gỉai Phóng Miền Nam [Liberate The South] the anthem of the “Viet Cong” – a rousing agitational number with bone-chilling lyrics. The innocuous young man sang in a froggy teen-ager voice:

to liberate the South, we decided to advance,

To exterminate the American imperialists, and destroy the country sellers.

Oh bones have broken, and blood has fallen, the hatred is rising high.

Our country has been separated for so long.

Here, the sacred Mekong, here, glorious Truong Son Mountains

Are urging us to advance to kill the enemy,

Shoulder to shoulder, under a common flag!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0K8okWdJ2xg&list=RD0K8okWdJ2xg&start_radio=1&t=37&t=0

“How bloodthirsty!” Tai, exclaimed. Even accounting for the hyperbole of a song designed to stir hatred to motivate action, these words made it clear that the insurgency did not intend to deal nicely with their enemies. One of the recurring and characteristic terms in the interviews was “diẹt gọn” (“exterminate completely,” or “wipe them off the face of the map!”). This was a language which General De Puy (“stomp them to death”) could understand.

University of Virginia classmates Nguyễn Mạnh Hùng and Tạ Văn Tài and wives 1967

The Year of the Big Change

The first year of interviewing Viet Cong prisoners and defectors in My Tho, from May 1965 to May 1966, was an incremental learning experience. The object of our study, the revolutionary movement in My Tho province (the revolutionary name for Dinh Tuong province) was in consant flux, and the situational environment which provide the context of the study was evolving rapidly as the American military presence dramatically escalated following the initial insertion of two Marine battalions in March 1965.

As summarized in my book The Vietnamese War, the revolutionary leaders called 1965 “the Year of the Big Change.”37 The “big change” was, of course, the deployment of large numbers of U.S. combat troops in Vietnam. This changed the nature of the war from a “special war” in which U.S. support took the form of advisors and economic assistance, to “limited war” in which the U.S. troops engaged directly in combat, but limited the scope of operations to South Vietnam (as the Korean War had limited the scope of hostilities within Korea). The conflict was transformed from a guerrilla war to a conventional war (on top of the continuing guerrilla struggle). This, in turn, led to a big change in policy – several changes, really. The first was a reversal of the brief leftist shift in revolutionary policy which had been aimed at intensifying land reform to benefit poor peasants, who would become the main political base for the military mobilization to finish off the war before the U.S. could intervene. Le Duan and other leaders had talked of an imminent “general offensive and uprising” at the beginning of the year, but this was replaced by the theme of “protracted war” after the size of the U.S. miltitary intervention became clear.

In historical retrospect the most important change that happened in 1965 was the accelleration of a vast socioeconomic transformation in the countryside that, in the long term, undermined the rural base of the revolution. Of course it was only many years later that this biggest change of all became obvious. Individual proprieters termed “middle peasants” (“trung nông,” who owned all the land they farmed and did rent any of it out or hire laborers) by the Viet Cong increased in prominence, and it was they, not landless peasants, who filled the void left by the demise of the landlord class. This was the “yeoman peasant class” that the U.S. had once hoped its policies would produce to become a bulwark against collectivization and a counterweight to the poor and landless peasants who were the social and political base of the revolution – began to emerge as the dominent force in the rural areas. As I wrote in The Vietnamese War; the “middle peasantization” that was already evident in 1965 “posed a dilemma for the revolution. On the one hand, it represented the obverse of the decline of the landlords, and was a sign of greater equity in land distribution. On the other hand, the Party did not trust the middle peasants, because their class interests would not necessarily carry them all the way to the end of even the ‘national democratic’ revolution, let alone the socialist revolution. In Long Hung village, the ‘cradle of the revolution’ in My Tho, ‘after the land reform was carried out in the village, the poor and very poor peasants contributed to the Front even more zealously. The rich and middle peasants began to leave their fields and orchards to go to the GVN areas.’ When the land distribution was first launched, the ‘middle peasants didn’t dare oppose it. When the Front gained complete control over the village, the middle peasants saw that the Front didn’t harm their interests and began to get to like the cadres and supported the Front from 1961 to 1963. But in 1964, when the Front imposed the agricultural tax in the village, they began to be disgruntled and left their homes to take refuge in the GVN areas. So now [1967] the village Front has concluded that the middle peasants belong to the vacillating and passive element of the national democratic revolution’” [DT185]. Since the middle peasants were already becoming the dominant class in the countryside in 1965, “this was an ominous portent for the revolution.”

We really didn’t fully comprehend the situation in My Tho we encountered in the spring and summer of 1965 until the following year, when we had more perspective on the events and were able to talk with more knowledgable people who were able to tell us more about what had been going on at that time. It is probably in the nature of a prolonged and in-depth study like ours in My Tho that understanding comes after the fact, usually long after the fact. Therefore it was pointless to expect any policy relevant breakthroughs derived from interview information in this early stage of the project.

This must have been a disappointment to Leon, who was constantly trying to beat military intelligence to the punch with “scoops” derived from the interviews. “As Goure saw it, his project was supposed to be militarily-oriented and to assist ‘the war effort.’ Although his team [in Saigon] continued to gather information regarding motivation and morale and although eventually several substantive studies did emerge from the data – the project, in his view, was not meant to be a mere continuation of the work of Zasloff and Donnell because that ‘was not what the chief of intelligence of he Air Force wanted, Of course not – he was not interested in that – he wanted to know about the war and the effectiveness of the war, how you fight the war better. The military was not interested in that kind of [social/political study] … It might have been set up that way originally, but it was certainly not the direction that they asked me to do.’ By the time he became involved, it seemed to him that the project was essentially an intelligence thing…[and that] ‘We’ve got the best damn intelligence in the war.’”38 Ironically, in trying to beat military intelligence to punch on relatively secondary issues like changes in military tactics and patterns of defection, Rand – the supreme think tank – missed the biggest story of the war, the accellerating erosion of the socioeconomic base of the revolution. Unfortunately for the U.S. and the Saigon government, this was a gradual and prolongued process and the consequences were not fully apparent until after the war was over. As the process was unfolding in the latter years of the war, it turned out that the losses in the Viet Cong’s socioeconomic base were not transferred to the side of the Saigon government, which proved unable to expand its support base with these dropouts from the revolutionary movement.

Leon gave frequent briefings on fast-breaking topics that emerged from the interviews, and would often design short questionaires to pursue these new issues. As Mai Elliott’s Rand book observes “Goure now became a star of the briefing circuit. He gave so many briefings that he could not recall the total. Goure ‘would give a briefing at the drop of a hat,’ some of the staff members would later say, and they would come to refer to those presentations as ‘quickies.’”39 I recall that Leon himself proudly referred to short written reports that he circulated in Vietnam as ‘quickies,” and considered the topicality and rapid response as an asset that was unique to Rand’s Saigon operation. His Rand colleagues in Santa Monica were less thrilled with the “quickies” since Leon used the pretext of timeliness to circumvent the normal Rand review process, which he surely know would not only be time-consuming, but critical of his findings.

The American staff members of Rand based in Saigon chafed under the burdens of being constantly mobililized into Leon’s “quickie” projects, and soon became disillusioned with the way in which Goure had transformed the original Motivation and Morale project. For me, being in My Tho provided a distance that afforded considerable independence. Afther the initial setting up of the program, I was left largely to my own devices. Occasionally, Leon tried to bring me into his plans to raise Rand’s visibility to the movers and shakers in Vietnam, but this happened rarely, and the few attempts to do so backfired, as we shall see. It also took some time to produce a formal written report on the study. The first was “A Look at the VC Cadres: Dinh Tuong Province 1965-1966, which was not published as a formal Rand Memorandum until March 1967. The second was “Pacification and the Viet Cong System in Dinh Tuong province: 1966-1967,” which, though submitted in October 1967, did not appear as a Rand Memorandum until January 1969.

In a way, positioning the My Tho project as a long-term study was consistant with the original rationale for restricting the study to a single province to get the depth and context which transitority visits to scattered sites around the country could not achieve. Given the limited number of higher level prisoners or defectors available in the confines of a single province at any given time, finding a significantly informative interview subject would be a rare event. It would be the cumulative contributions of many lower level interviewees to establish trends over time rather than the revelations of a “D” about the higher levels and policy aspects of the revolution that would allow us to achieve our goal of better understanding the state of war in one small slice of it, and obtaining some kind of reality check on how the war was progressing in at least one significant area.

A good illustration of this is what happened in the first two months of interviewing in My Tho. We did not yet have an established base there, but commuted to MyTho town, checked into the one barely tolerable hotel, and proceeded to the the province Chieu Hoi Center. We did not, at the beginning have the contacts to gain access to prisoners.Only when Nguyễn Hữu Phước joined us in July 1965 were we able to talk with prisoners, using his contacts with military and security officials. Phước became our entrée to military and civilian prisoners.

After a few interviews with village cadres who had defected, we spent the next several weeks learning the stories of some representative members of a large group of young men who had been forcibly drafted and marched out of the Mekong Delta, headed for the Central Highlands, where they would serve as fillers to Viet Cong main force units being reinforced to fight the Americans.

The compulsory drafting of recruits by the Viet Cong had started in 1964, in some areas as early as 1963, and was directly related to Hanoi’s December 1963 decision to “go for broke” and try to militarily defeat the Saigon government while it was still in disarray after the Diem coup and before the Americans could intervene. Also in 1964 compulsory taxation also replaced “contributions” to the revolution which had been compulsory in all but name. Now the consequences of defying the exactions demanded by the revolution were extremely serious, as all pretense of persuasion was abandoned. The combination of draft and taxes created a backlash against the revolutionary movement and created great problems for the local cadres who had to enforce these unpopular policies. The first phase of the My Tho study examined this issue in detail, and it was the subject of the first report issued on the My Tho research.

By chance, the wave of compulsory drafting reached its peak in May and June of 1965 just as we were beginning the study. After that, the intervention of U.S. combat troops compelled the revolution to abandon its “go for broke” approach, and shift to a policy of protracted war which abandoned the buildup of conventional main force troops in the Iron Triangle and the Central Highlands, and dramatically reduced the transfer of young men from the Mekong Delta to those areas. Sixteen of the first 33 interviews were with new recruits, who had been forcibly dragooned in early May 1965, in groups of a dozen or so from villages in the central part of the province. They were marched to a central collection point near the abandoned Buddhist temple Chùa Phật Đá in Cai Lay district.

Chùa Phật Đá circa 1999. On right is the nearby Nguyễn Văn Tiếp canal on the edge of the Plain of Reeds.

From Chùa Phật Đá the consolidated groups of draftees crossed the Plain of Reeds into Tay Ninh province, near the Cambodian border. Most of the group that we interviewed had ended up on the Iron Triangle area in the Bời Lời woods, where I had witnessed the forced evacuation of a hamlet near the village of Bến Sức earlier that year when I was still with MACV. Providentially for these new recruits the defoliation of the Bời Lời woods in the Iron Triangle that had already been done was sufficient to allow them to see a path of escape, and large numbers of them defected.

We didn’t learn a great deal from these new recruits other than the fact that Chùa Phật Đá seemed to be the central nexus of their communications and liaison system. This was an early indication that the image of the guerrilla as someone who was “everywhere and nowhere,” disconnected from the geography of their area of operations, was a myth.40 As we later discovered, the liaison routes and base structure of the Viet Cong in Dinh Tuong were relatively fixed, although they were used in an unpredictable rotation. In a way this was the beginning of our discovery of the geographical “face” of what I came to call the “Viet Cong System” in My Tho. Saigon had its “Dinh Tuong province” and the revolution had its “My Tho province.” They both existed within more or less the same provincial boundary (although “Viet Cong” My Tho province included an additional district, Go Cong, that was a separate province on the GVN side), but an overlay of areas of control, routes of communication and the like would have shown that each side’s grid filled in the empty spaces left by the other. The difference was that large sections of the Viet Cong grid were inactive most of the time, until they were needed for specific purposes. This insight was sparked by a pivotal interview that Cầu did with a deputy platoon leader of the 514th battalion [DT110] in March 1966 – another example of Cầu’s ability to dig beneath the surface.

His observation that the 514th and other concentrated units operating in Dinh Tuong province actually had a network of prepared fortified positions that were the equivalent to the military posts of the GVN. The only difference was that they were only sporadically occupied in random patterns that kept the GVN guessing which ones they might be in at any given time. It was like the shell game once proposed by the US to set up an underground network of missile sites, which could contain mobile missiles connected by rail lines hidden from sight, that would create uncertainty on the part of Russia as to which sites were occupied, and complicate any counterforce strike plans they might have.41

From this basic insight, we were able to discover the elaborate network of communication and supply routes that connected these prepared fortification, and from that we learned how this protected the political cadres in Viet Cong controlled areas by casting a “psychological umbrella of security” over the “liberated areas” by raising the threshold of force required by the GVN to enter a Viet Cong zone simply by creating uncertainty as to whether or not they might meet a large Viet Cong force. The large and cumbersome “sweep” operations of the ARVN Seventh Division were always known in advance to the Viet Cong, who simply left the area until the operation was over. It was not until the U.S. Ninth Division came into the province, especially in the post-Tet 1968 years that this system broke down.

We began early on to get a more detailed picture of a few villages because of the defections of several people from the same village whose stories could be cross-checked amplified and expanded. In general this did not happen until after six months or so of the study, but one village that stood out early on was Hồi Cư in Cái Bè district. It was an elongated village that connected the Plain of Reeds with a critical segment of Highway 4, the lifeline route of the GVN which ran through the middle of the province, cutting into northern and southern sectors.

Because of this geographical quirk, close to key GVN locations but connecting to a secure base area for the Viet Cong, this village was important to the Viet Cong.

Whatever “quickie” intelligence might have been derived from our interviews of the fleeing draftees would have been misleading. Instead of being a harbinger of a new phase in the war, it was was the last gasp of a policy (”go for broke”) that had already been abandoned as obsolete. We did have enough sense to focus on the impact that the escalation of draft and taxes had on the relationship between the local cadres and the rural population in both Viet Cong-controlled and contested areas.

Another development that accellerated in 1965 which began to show up in the interviews was the depopulation of the countryside which, over the remainder of the war intensified and created a massive demographic shift that drove the socioeconomic ascendancy of the middle peasants. In the late 1960s Harvard political scientist Samuel Huntington cavalierly termed this “forced draft urbanization,” which meant, essentially, bombing and shelling the peasants out of the countryside and forcing them to take refuge in the cities where, as Huntington noted, they could be more easily controlled by the Saigon government. Leon was unfazed by the “collateral damage” of his recommended policy of intensive bombing of the rural areas. In some ways he anticipated Huntington with his pithy, if cynical, remark “we’ve got the onus, let’s get the bonus.” In other words, we should turn the negative of “collatoral damage” into the positive of pushing the peasants into areas were they could be more easily controlled.

In Dinh Tuong province, a “free fire zone” was established in the heartland of the province (the “20-7 Zone” named by the Viet Cong in commemoration of the July 20, 1954 signing of the Geneva Accords). This was the most heavily populated and prosperous area in the province, and its central location was vital to the Viet Cong base structure and supply routes. The people who lived there were told in the announcement (audio clip below) that starting from January 15, 1965, the GVN would bomb and fire artillery at will, and anyone who chose to remain in this area would not be eligible for compensation for loss of life or property. The resulting exodus of refugees began the demographic hollowing out of the rural villages, which became the main engine of “pacification” for the remainder the war.

GVN announcement of establishment of a “free fire zone” in Dinh Tuong as of January 15, 1965

After the war, Chín Công, the shadowy province leader of the Viet Cong in My Tho described the beginnings of the great rural demographic shift that began in 1965.

Going into 1965 the enemy fiercely and destructively fired into the liberated area, driving the people out to live along the roadsides, while they zealously prepared for a limited war [the intervention of U.S. troops]. The situation became difficult. How could we hold the people in the liberated areas? Before, when they [the GVN] used infantry to grind down and round up the people, we could use the “three spearheads” of political and military action along with military proselytizing to stop them, because they were flesh-and-blood human beings. Now the instrument used is iron and steel raining down from the skies. The gang that does this is not there on the spot, so how can you stop them? The Current Affairs Section [of the province Party committee] constantly met to discuss this. I concluded that we should resolve to mobilize everyone, cadres, soldiers, and people, to dare to cling to their turf. The leadership must set the example, and the fiercer and more difficult it is, the more they need to set an example. Brother Muoi Ha raised the point that the people in Ap Bac had spontaneously left for the open rice fields and set up straw huts at the edge of their fields. At the beginning they only set up some crude straw roofs as shelters for them during the day, and returned home at night. But later, as the [GVN] continued to shell into the treelines [where the settlements were], they built more substantial houses in the fields. The other brothers said that it was not only Ap Bac that did this. By day the people wore white clothes and moved back and forth. When enemy planes came to strafe, they just went about their business normally and it appears that the enemy got used to this, so that this became a way of becoming legal with them. From this phenomenon a solution to the problem of holding onto the people gradually emerged.42

Although, as Chín Công asserts, the Viet Cong eventually found ways to diminish the impact of this rural reconfiguration of the population, this dispersal of the village settlements had an inevitable impact on the Viet Cong ability to mobilize the population.