2

Some experiences leave an indelible impression not because they illustrate or represent a phase in life’s journey but because they seem disconnected from it, standing outside its arc. That is the way I remember my most vivid recollection of my first month in Vietnam, following my arrival in Saigon in October 1963. The incident jarred me out the familiar contours of my previous life experience, and left me standing on the brink of a world whose outlines I could only dimly grasp. It was the moment that the limits of my understanding of the world around me were starkly revealed.

I can no longer recall what led up to it, or what followed it, but it was my first experience of being swept up in a collective galvanizing experience – other than the late night rallies in front of a massive bonfire preceding Deerfield Academy’s annual football game against its hated rival Choate, that whipped us into a frenzy (Beat Choate!!) that would have put the Nuremberg rallies to shame. This was totally alien from anything I had previously encountered. Standing in a residential alley in front of my fiancée’s family home, surrounded by a crowd of Vietnamese gesticulating to the heavens with extreme agitation left an indelible memory.

As Mai, who was standing next to me, recalled years later in her family memoir, “One day I heard a commotion in our alley late in the morning. I ran out and noticed a crowd of people peering at the sky and saying, ‘The sun is spinning! The sun is spinning!’ I looked up and saw – to my amazement – that the sun was etched with a dark circle that was turning very fast.” Along with everyone else she was baffled. “Perhaps there is scientific explanation for this strange phenomenon, but none of us could think of one. Perhaps, induced by hysteria, we were only imagining things. We stood there, awed by what we had witnessed. My neighbors told one another that this could mean only one thing: Diem was going to be overthrown.” (p.298) It is emblematic of the power of this shared collective cultural moment among Vietnamese that Mai does not remember my presence at the event. Despite my physical presence among the crowd, as an uncomprehending foreigner, I was outside the framework of that remembered moment – a disconnect from the collective event that I was keenly aware of at the time.

As Mai later surmised, it could have been due to mass hysteria triggered by the volatility of the Saigon political atmosphere in the last days of the Diem regime. Every Vietnamese was immersed in a shared political culture in which, as illustrated by Chinese popular historical novels like the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, the loss of the mandate to rule as inevitably prefigured by strange natural phenomenon. “When a ruler violates this mandate, heaven sends the signs that he will be punished, usually natural disasters like earthquakes or unnatural phenomena like roosters suddenly laying eggs.” As Diem’s unpopularity was ratcheted up by events like the self immolation of Buddhist monks, all of Saigon was on edge, and instinctively awaited the confirming signs of heaven’s disfavor or the current regime, which now seemed at hand. Indeed the “sun is spinning” episode was one of the experiences of my life in which the atmosphere could truly be characterized as “electric.”

So the perception of the corona around the sun rotating could have been mass hysteria, but I saw it too (though I wonder in retrospect how I could have been staring straight at the sun) – an alien outside observer, not knowing the deeper significance of what I was witnessing. I even understood what the crowd was saying, though it was a phrase that I had never heard in the 47 weeks of intensive Vietnamese language training that I had just completed in Monterey California: “mặt trời quay! mặt trời quay!” I understood the literal meaning of the words – “the sun is turning” but, unlike the crowd of Vietnamese in the alley, I had no clue of the deeper meaning that these words, and what the phenomenon which we all observed, signified.

It is only in retrospect that I can recognize how aptly this incident reflected the chasm in cultural understanding that separated Americans from the Vietnamese whose fate they had come to determine. The sensible program to train Americans in the Vietnamese language to fill the linguistic gap between official America and the society it hoped to transform, could only assure communication at the most superficial and literal levels. Even the most basic cultural underpinnings of real communication would take much longer to acquire.

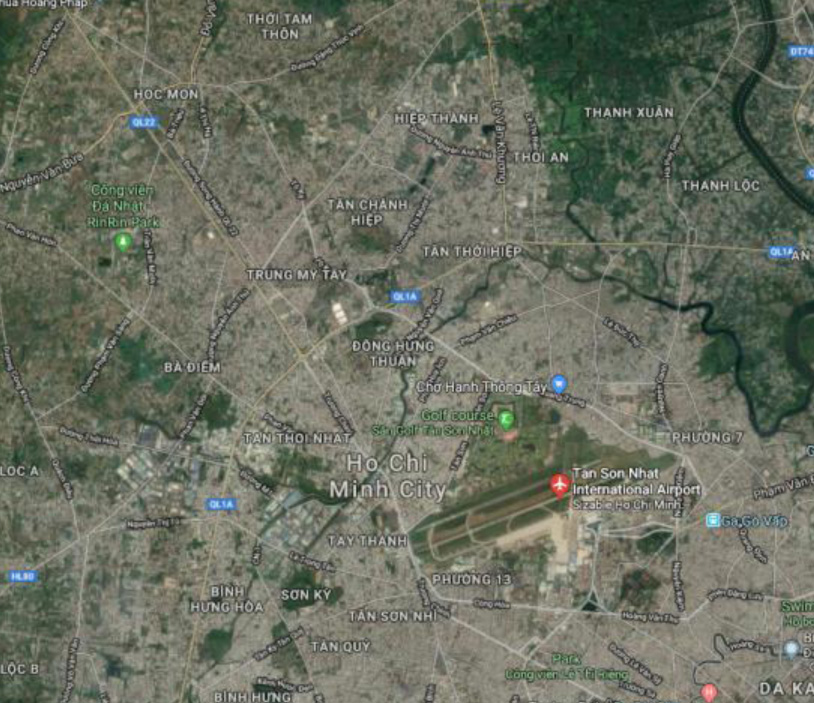

And even with a rudimentary functional grasp of the language and the personal ties with Vietnamese society provided by my connections with Mai, and her cohort of American-educated Vietnamese who had served as my initial introduction to a country about which I had been totally ignorant, I was disoriented by my initial encounters with Vietnam. The summertime swelter of Boston and Virginia had not prepared me for the blast-furnace heat of Saigon which greeted us as we stepped off the plane at Tân Sơn Nhứt Airbase (this is a common South Vietnamese spelling of Tân Sơn Nhất airport, based on the Southern dialect pronunciation), and moved the short distance on the military side of the base to our barracks in the adjacent compound of the Third Radio Reconnaissance Unit (3rd RRU) which would be my home for the next several months.

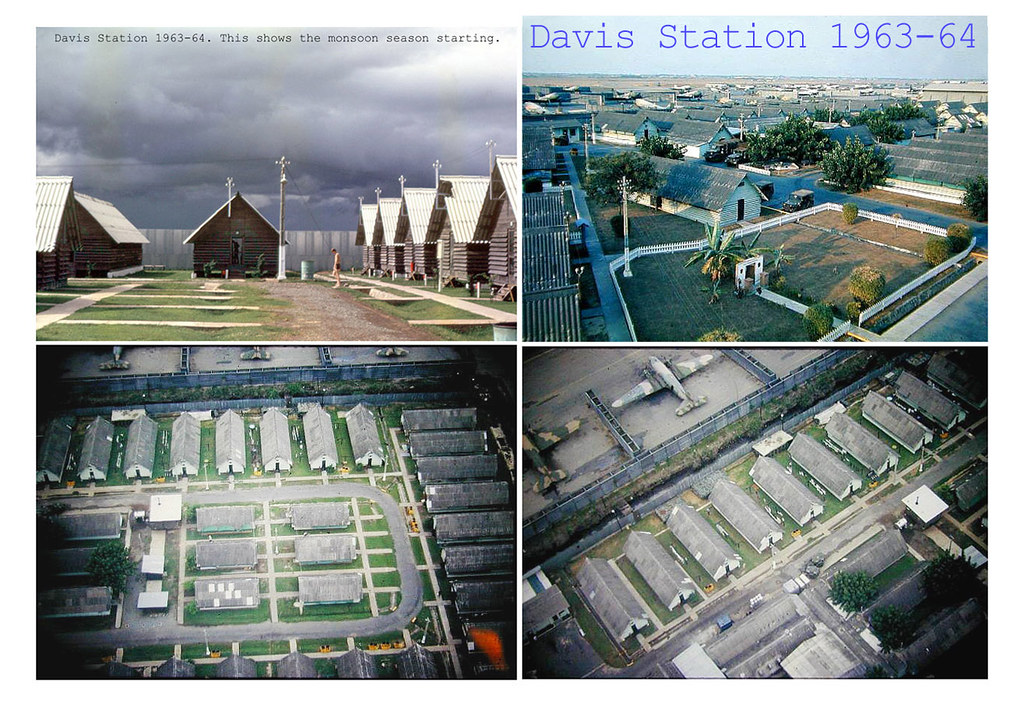

The 3rd Radio Reconnaissance Unit was a cover designation for the 400th Operations Unit (Provisional) of the Army Security Agency.1 The “cover,” intended to disguise the connection with the super-secret Army Security Agency, was fairly transparent and, I’m sure, did not deceive anyone. It was formed as a result of President Kennedy’s April 1961 decision to beef up America’s signals intelligence capabilities. “On 13 May 1961 92 personnel of the 3rd RRU landed at Tân Sơn Nhứt Air Force Base, located just west of Saigon proper. … The 3rd RRU’s entry marked the first time that an entire army unit had deployed to South Vietnam; previously only individual advisors had been assigned. The headquarters and processing elements of the 3rd RRU immediately found a home in an empty warehouse.” Most of the first contingent of the 3rd RRU lived downtown in the Majestic Hotel, the grandest accommodations available in Saigon at that time.2

By the time I arrived two years later, the initial base had been expanded and all unit members lived there. We lived in wooden barracks, some with rudimentary protection from sandbags. Although the base was barren and dusty, I still recall the musky odor of decomposing tropical vegetation which suffused the military side of Tan Son Nhut air base, before it was overwhelmed by the gas fumes of aircraft operations as the last traces of the reclaimed jungle on which the base had been built were submerged in the mechanical detritus of the massive military operations of the U.S. air force.

John Buquoi, a fellow linguist from Monterey who was a contemporary at the 3rd RRU, and whose brilliant poetry and remarkable personal experiences I will mention in this chapter, arrived around the same time I did, and later wrote the following memorable description of the smells that the first-time visitor to Saigon encountered in 1963. “It was a sweltering tropical mid-afternoon, and, as Thomas Fowler would say, it was the smell that was the first thing that hit him, and then the heat. The smell an unfamiliar, exotic, sickly sweet mixture of tropical fruits, flowers, sea breezes, rotting vegetation, diesel fumes, piss, gunpowder and cordite was wholly different than anything in his experience. It was not offensive, rather strangely enticing, erotic almost, but, very different and in no way offensive as he might have expected. They were scents and odors which dissolved in his blood and attached themselves to him from that moment, for life; scents which, fifty years and ten thousand miles later, he would still conjure from memory and be overcome with nostalgia for the place and the time and the people, the youthful adventure of it all.”[1]

Entrance to Davis Station, base of the 3rd Radio Research Unit circa 1963

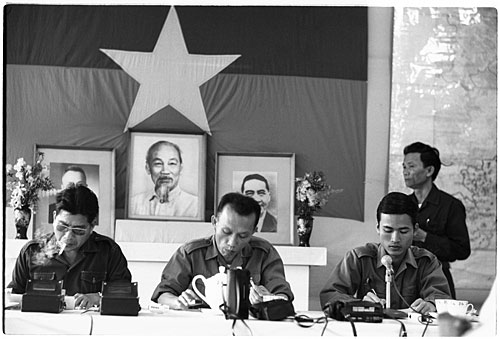

Ten years later when I returned to Davis Station in 1973 with Jacques Leslie of the Los Angeles Times, it had become the headquarters of the delegation of the Provisional Revolutionary Government (PRG), newly arrived after the Paris Peace Accords of January 1973. They held periodic press conferences there for the benefit of the foreign press. Not only had the barracks of Davis Station changed hands, the former presence of the 3rd RRU had been completely effaced, and the tropical vegetation inside the base restored. Journalist John Spragens reported “Inside the compound the atmosphere is relaxed. The road is lined with banana trees and flowers planted by the Hanoi and PRG delegations, and delegation members greet correspondents as they walk the few dozen yards from the gate to the briefing room.”3

Provisional Revolutionary Government delegation at their Davis Station headquarters, April 1973.

One former member of the 3rd RRU describes the early years of the unit. “For the first time, a U.S. military unit had been sent to Vietnam as an operational unit. They were not advisors; they were a fully functioning field unit established to provide intelligence to [MACV].” The job was “to intercept enemy radio communications, break codes, analyze radio traffic, and utilize various methods of monitoring signal intelligence (SIGINT). … Their mission was conducted in what can only be described as ‘third world’ conditions, in the worst possible sense of the term. Their main operational facility was an old aircraft hangar at the base, which had no air-conditioning. Temperatures inside regularly rose about 100 degrees, and then the monsoon rains came. Water poured through the doors and flooded the entire area to a depth of several inches. The various operational sections were separated by stacks of C-ration boxes, and the analysts worked together at long tables pieced together from plywood and scrap lumber. There were no chairs so the tables were built high enough that the men could stand while they worked.”4

https://www.flickr.com/photos/13476480@N07/7743872460/in/album-72157630998344742/

3rd Radio Reconnaissance Unit barracks, Davis Station circa 1963

Outside the gates of the Davis Station compound, a few three wheel Lambrettas, converted to hold up to a dozen Vietnamese (and, of course correspondingly fewer larger Americans) served as a shuttle to take passengers to the main gate on the military side of the airport.

Three wheeled Lambrettas wait for passengers near the Davis Station main gate

Not long after my arrival in Vietnam I learned first-hand the distinction between the military and civilian sides of Tân Sơn Nhất airport. My first excursion out of the Tân Sơn Nhất base was on my first full day in Vietnam. I had not yet been assigned to any job at the 3rd RRU, and my time was my own. My first thought was to find Mai who had herself returned to Vietnam only a few weeks earlier in October 1963 after graduating from Georgetown University. Wearing civilian clothes, I climbed on to the Lambretta shuttle which took me from the Davis Station gate to the main military gate of Tân Sơn Nhất.

Tan Son Nhut AB, Main Gate. 1963. Photographer: Robert G. Anisko, 1962-1963

http://www.vspa.com/tsn-gates-and-posts.htm

The military gate, later called O-51, was over a half mile from the main civilian entrance to Tan Son Nhut airport, but I didn’t realize this at the time. Outside the military gate was a cluster of blue and white Renault Saigon taxis.

I was confident that my functional Vietnamese language skills would get me where I needed to go. For the moment, I was focused on finding Mai’s house and not on how to get back to the base (I assumed I would simply retrace my steps). I told the taxi driver to take me to 380/5 Công Lý. Công Lý was the main avenue connecting downtown Saigon with the airport. Mai’s house (number 5) was actually in a small hem or unpaved alley of contiguous stucco houses that, in this case, had been built to house civil servants after 1954.

Mai’s family home in the hẻm in front of their house, 1972.

The hẻm did not directly connect with Công Lý and there were a number of hẻm linked to the main alley leading from Công Lý, so it took a bit of trial and error to find. Later I would learn that the taxi drivers identified the general location along Công Lý where the main turnoff to the hem was, as being just below what later became internationally known as the “McNamara Bridge,” spanning a small creek flowing under Công Lý. This was the place where the Viet Cong terrorist Nguyễn văn Trỗi had planted a bomb intended to assassinate McNamara in 1964. For the Vietnamese, however, it was always the Cầu Bạc Má Hồng (Macmahon was the colonial era designation for Công Lý avenue, named for a French official. The literal meaning of the transliterated phrase was “bridge of a great beauty with a tragic destiny.” – derived from a famous line in Vietnam’s immortal epic poem, Tale of Kieu. I would only have to tell the cab driver “take me to the Cầu Bạc Má Hồng” and, as we approached the bridge tell him to take the turn-off to the hẻm.

But, on my first full day in Vietnam, I didn’t yet have this local knowledge, and had to locate the hẻm by trial and error. I got out of the taxi at the head of the first offshoot hẻm and walked down the row of houses until I found number 5. I asked someone in front of the house “Đây có phải là nhà cúa Ông Dương Thiệu Chi không?” (Is this the house of Mr. Duong Thieu Chi) which was the name of Mai’s father. My unexpected presence had created a commotion in the alley, and consternation in Mai’s house. She was not home at the time, and the neighbors were astounded to see me coming, probably the first American who had ever set foot in this hẻm. As would often be the case in Vietnam, I did not get a response to my question posed in Vietnamese because the idea that an American could speak the language was so improbable that even if I had spoken with native fluency it would have only registered as a babble of incomprehensible sounds.

Mai’s older sister Binh recalled that though she lived next door, she happened to be in Mai’s house when I arrived. As people inside the house spotted me, Mai’s father said “How come there is an American coming to our house?” and instructed Binh to go out and see what I wanted since she was the only one around who spoke some English. Binh recalled, “David was still standing at the door, so I showed off my English by asking ‘who are you looking for?’ David replied in English ‘I am a friend of Mai’s, and have come to see her. Is she at home?’ I said to Father, ‘he is a friend of Mai’s and has come to see her. Father responded ‘tell him that Mai isn’t home but will probably return soon, and ask him where he is staying at present.’ The entire family was astounded when David replied in Vietnamese ‘I am staying at the military base in Tân Sơn Nhất.’ The entire family was astonished and delighted, and Father exclaimed, ‘This American knows Vietnamese!” and he invited David into the house. David and Father began to converse, but I had gone into the back room so I didn’t know what they discussed.”5

Mai eventually returned home and we were of course delighted that we had managed to re-connect, since our last communication had been before either of us had departed the United States, and because I didn’t know exactly where I would be, we could not make specific plans to get together. I had only Mai’s complicated street address as a guide. Now, however, we knew where I would be for the immediate future, and I knew how to reach Mai. Although I did not yet know what my assignment would be (and therefore what my schedule would be) we made arrangements to meet again soon.

My trip back to base was, unexpectedly, an adventure. I got in a blue and white taxi and told the driver to take me to Tân Sơn Nhất. Not knowing the layout of the base, I didn’t realize that he had taken the turn to the civilian side of the airbase instead of the military side. I got off at the civilian terminal, feeling that something was not quite right – I didn’t see the American MP’s and the guarded gate, but only a civilian passenger entrance. I walked inside the terminal, totally disoriented. The only person in sight was a uniformed Indian Army officer, replete with turban. I was vaguely aware that there was a diplomatic sensitivity to the military presence of Americans – especially those involved in combat related tasks like signals intelligence, and the International Control Commission, of which this Indian officer was clearly a member, was there precisely to ensure that there were no American combat troops in Vietnam in violation of the 1954 Geneva Agreements (recall that the 3rd RRU was the first complete unit sent to Vietnam to support combat operations), so it was not very appropriate to ask him, of all people, where the American military base to which the ICC was turning a blind eye was located. If he had a sense of humor, he might have referred me to an ASA recruiting poster which underlined that an advantage of signing up for that branch was that you would not be sent to Vietnam.

However, I felt I had no recourse other than to ask him how I could get from the civilian terminal to the American military base on the other side of the airport. He was probably mildly amused by the situation, but took it stride and pointed me in a general direction. By this time, the civilian airport was empty and there were no more blue and white taxis. So I hailed a pedicab and told the driver vaguely to take me to the other side of the base. By this time it was dark, and the streets adjacent to Tân Sơn Nhất were deserted. I don’t recall whether the pedicab driver simply took a wrong route because he was not clear that I wanted to reach the military gate to the airport, or whether we simply passed the dimly lit gate and I didn’t notice it.

Tân Sơn Nhất airbase circa 1963.

Main civilian gate and military gate 0-51 of Tân Sơn Nhất airport 1963

After about ten minutes I began to notice that the urban landscape had changed to open countryside. I later discovered that I was headed toward Hóc Môn, a traditional revolutionary stronghold, along the road which led to Tay Ninh. More recently Hóc Môn has become the symbol of the rapidity of urban sprawl which has obliterated the once sharp distinction between urban and rural in the massive and rapidly expanding urban sprawl of Saigon. Barely twenty kilometers from downtown Saigon, it is sometimes considered the “edge” where urban meets rural, though Erik Harms’ brilliant book of that name persuasively contests the idea that there is such a sharp dividing line, and points to the many overlapping indicators of both rural and urban dimensions of Hóc Môn, where he did his research.

Harms describes travelling from Hóc Môn in the early 2000s on motor bike, “starting down the road toward Saigon, enjoying the cool but dusty breeze. This was the edge of Hóc Môn, at the boundary of District 12, where Highway 22 turns into the Boulevard of the August Revolution, where the road commemorating Hồ Chí Minh’s revolution becomes the road to Ho Chi Minh City itself. On the map, this marker between the inner-city district and the outercity district appears substantial and seems to mark a divide. Move one direction and you will go in (đi vào) to the numbered districts of Ho Chi Minh City; the other way leads out (ra) to Hóc Môn. But the divide is more symbolic than real. Hóc Môn is also part of (thuộc) Ho Chi Minh City, and there seems no objective difference between the density or urban character of the streets on either side of the planners’ arbitrary divide. In Hóc Môn, Thành and I found ourselves both inside of Ho Chi Minh City and outside it.”6

In 1963, unwittingly travelling along the road to Hóc Môn, I perceived a sharp and unmistakable dividing line between city and countryside less than a few kilometers from Tan Son Nhut. Suddenly I noticed that the road was eerily deserted and no longer lit by street lamps. It was by now pitch black in the late evening. The only sound was the whir of breeze created by the pedicab and the noise of the rotating chain driven by the pedals. I was clearly headed in the wrong direction and into the unknown. I had read Graham Greene’s Quiet American and uneasily recalled the scene where Pyle and Fowler broke down along the same deserted road I was now travelling, and barely escaped capture by the Viet Minh. Although I didn’t know it at the time, this was also probably the road where Specialist James Davis had been ambushed and killed while on an operation in 1961, becoming the first KIA of the 3rd RRU. I told the pedicab driver to turn around and retrace our route.

Eventually we arrived at the gate to the military base and, fortunately, this time I recognized where I was. Somehow I managed to get back to Davis Station, and regain my orientation to my new surroundings. It was probably a good thing that I learned my limitations in negotiating the most simple challenges in Vietnam early on. My sense of complacency based on the idea that speaking rudimentary Vietnamese would solve every problem dissipated, and I would encounter many instances of the perils of relying on a false sense of competence in the months and years to come.

Assistant Mail Clerk

My indeterminate status at the 3rd Radio Reconnaissance unit dragged on for days, and then weeks. All the linguist slots at Davis Station were filled and, while waiting for something to open up elsewhere, I was shuttled around between a series of menial jobs. First was in the company orderly room (administrative office), presided over by a First Sergeant who, coming from the South like many NCO “lifers” (career soldiers) as we called them, had a variety of homespun expressions. His favorite was “well, you ain’t just a’whistling Dixie.” to express his approval of some underling’s remark. Behind his back, the slacker who served as company clerk called him (in Vietnamese) “bạch xà” (white snake) with the xà a prolonged sinister hissing sound trailing off into nothingness. I later learned from John Buquoi that this descriptor originated from Berkley Cook, who was the senior linguist at the 3rd RRU during the late ’63-mid ’64 period, and the phrase caught on even among non-linguists. It might have been because of the First Sergeant’s graying hair or possibly simply because it sounded disrespectful.

My few days in the orderly room taught me a valuable lesson about how the army works. The reason that the slacker who dissed the First Sergeant was able to get away with his insolence (which he did little to disguise) was that he was the only one in the entire unit who had mastered the tedious details of how to fill out a perfect “morning report” which was the most essential cornerstone document of the entire military administrative command system. As Wikipedia describes it “In the United States Army, the ‘morning report’ was a document produced every morning for every basic unit of the Army, by the unit clerk, detailing personnel changes for the previous day. The morning report supported strength accountability from before World War II until the introduction of SIDPERS during the 1970s.The report was signed by the unit’s Commanding officer, and submitted to the appropriate higher administrative unit. It was the source for tabulation of the Army’s centralized personnel records. The morning report detailed changes in the status of soldiers in the unit on the day the change occurred, including for example, transfers to or from the unit, temporarily assignment elsewhere (TDY), on leave, promotion or demotion, and other such events. Familiar abbreviations such as KIA (killed in action), AWOL (absent without leave), WIA (wounded in action), and MIA (missing in action) were the authorized notations used on the morning report for those statuses. When a soldier was transferred to or from another unit, his or her orders specified an Effective Date of Change of Strength Accountability (EDCSA) specifying the exact date that the soldier is counted as leaving one unit and officially joining the other. The morning reports of the respective units will show the soldier transferred out, or in, on that date, as the case may be.”7

Failure to submit a spotlessly clean and accurate morning report to the next highest level would be an indelible black mark on the First Sergeant (and the company commander) and a blot on their efficiency reports that would affect future promotions. The company clerk was a living refutation of the Army’s contention that there “are no indispensible soldiers” and that everyone is an interchangeable and replaceable cog in a well-oiled machine. Without this clerk the administrative structure of the unit would have collapsed. The same could not be said for anyone else.

As a result, the First Sergeant generally ignored the insubordinate attitude of his company clerk. The clerk was not the only slacker at company headquarters. Another low level enlisted man was equally impertinent to his superiors. He also enjoyed hassling the Vietnamese waitresses in the dining hall. Like the company clerk, he had one go-to Vietnamese expression. Leering at a waitress he would say “Đẹp quá!” (really beautiful), drawing out the “quaaaaa” in a languid and lewdly suggestive drawl, with the tone trailing off in a downward direction rather than the correct short rising tone, and bore no relation to the sharp and clipped way “quá” was pronounced by Vietnamese who generally used it as genuine compliment rather than a crude come-on.

One shouldn’t conclude from these cases that the army, or at least the 3rd RRU was nothing but slackers. The specialists with technical training worked hard and took pride in doing a good job – though I never actually got to see them in action at their highly classified trade. An even more remarkable case of dedication to duty was the company mail clerk. I was assigned to assist him for a few days – long enough to learn what a stifling and mind-numbing task this was. The mail clerk was either a specialist fourth class (corporal) like me, or a specialist fifth class (E-5 or fifth grade enlisted man, equivalent to a sergeant, but without the authority that a sergeant had, as a non-commissioned officer (NCO) to order people of lesser rank around). In short, not a high ranking enlisted man and certainly not a “lifer.” I hated the job so much I tried to get away with doing as little as possible – especially since I knew it was temporary and I would never derive any satisfaction from doing the job well, and anything I did only got in the way of the hyper-efficient designated mail clerk. But unlike me, the mail clerk threw himself into his monotonous task with energy, imagination and efficiency. The explanation for this anomaly, I concluded, was that he was a Swede from Minnesota, of great natural integrity and driven to his astounding work ethic by an unbending Lutheran conscience. The miracle of the draft-era army, I discovered, was how many of these self-motivated soldiers performed at a level far above the usual standard of Army mediocrity. When I later read Casualties of War, Daniel Lang’s harrowing true account of a horrific war crime (the rape and murder of a young Vietnamese woman by G.I. members of a patrol who had abducted her), I immediately recognized the same personality type as the mail clerk in Eriksson, the straight-shooter (played by Michael J. Fox in the movie version) who blew the whistle on his fellow soldiers who had perpetrated the crime, placing himself in great danger to uphold what he knew to be right. Much as I admired the mail clerk’s dedication, I couldn’t match it or even aspire to it. I just wanted to get out of there.

My next job was only slightly less tedious. Because I had a top-secret cryptographic clearance (a requirement for being a member of the Army Security Agency branch, which was what got me to language school at Monterey), I was allowed to enter the highly classified working quarters of the cryptanalysts and other signals intelligence personnel to supervise the Vietnamese workers who had been brought in to spruce things up these shabby and Spartan working spaces with a coat of paint. This struck me as typical Army idiocy; my presence there would not prevent the uncleared Vietnamese from seeing things they shouldn’t. Who knew if there were any Viet Cong among them?

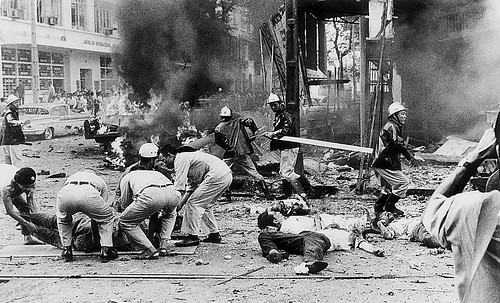

A month after my arrival in Vietnam, the coup which overthrew President Ngo Dinh Diem that had been prefigured by the spinning sun, broke out, on November 3, 1963. Since I was an unassigned body hanging around the orderly room, the company commander requisitioned me to follow him around with a clipboard and note pad, in case he had to issue orders as he rushed from one side of the base to another inspecting the unit’s defensive perimeter which was right next to the military flight line. A rumor swept through the camp that a Diemist airborne counter-assault would land on the adjacent runway, and that the area would be used as a base for assaulting the coup forces.

Ironically, given the fact that we were a signals unit and monitored friendly as well as enemy communications, in the sphere of the company commander there seemed to be little reliable information about what was happening in other parts of Saigon, or the country at large. A few of the linguists knew much more about the coup plotters, but apparently much less about the Diem forces with which we were nominally allied. I discovered later from my Monterey classmate John Buquoi that the company commander wasn’t even cleared to know about any of the classified work regarding signals intelligence, and was only there to run the daily routine of living for the members of the 3rd.

After an hour or so of pointless running around the base behind the company commander, he saw how useless my services were to him, and gave me a different assignment. We came across an M-60 machine gun, pointed at the flight line which, for some reason, was unattended. I was ordered to man the gun until further orders. The company commander didn’t bother to ask whether I, a linguist, knew how to operate an M-60 (I didn’t), but it at least got me out of his way. After several hours we learned that the anticipated counterattack on the adjacent flight line would not take place, and that the coup forces were now in full control of the situation. Our flimsy perimeter defense was disbanded and everyone went back to their jobs (except me, because I still didn’t have one).

Life in the barracks proceeded uneventfully until, a few weeks later, I was awoken by a great commotion. President Kennedy had been shot. It is said that every one of my generation remembers exactly where they were when they learned the tragic news. I certainly do. I was awakened from a sound sleep in our barracks with the unprecedented shock of learning that our President had been shot, halfway around the world, while we were in Vietnam supposedly defending the frontiers of freedom. In the view of many Vietnamese, Kennedy’s own assassination was Heaven’s judgment on his role in Diem’s death. It was only much later that I learned of the American complicity in this coup, which at least would make more sense if itwas to repulse a Diem counter-attack on the coup forces whom we secretly instigated. But of course, I didn’t know that at the time. I also didn’t realize, until much later, that the Diem coup was the point of no return for American direct intervention in Vietnam, and the point at which American complicity made it politically impossible to withdraw, but also impossible to win the war that followed.

Only recently did I discover that John Buquoi, one of my Monterey classmates who was at the 3rd RRU during the coup, had published a book of poetry – including a poem about how the coup and the American role in it affected him.

Oversight by John Buquoi

saì gòn

november 1-2, 1963

tapped into conversations

between the general staff,

we listened to the chaos

of the bloody coup d’etat

in the ritual dying

of the cut off palace guard

and the manic hide and seek

of the hunt for two brothers,

ngô đình diệm ‘ông nhu’

betrayed now both by ourselves

and those trusted generals

baying down their escape trail

along the bloody darkness

to that final fatal dawn.

but we didn’t recognize

the tangled karmic pivot,

as the circling wheel of fate

on this steamy tropic day

turned their little local war

toward our owned holocaust

of soon on-rushed fire and blood

John Buquoi outside Saigon, 1963 (in steel helmet and holding a pack of cigarettes).

In the photo above on John Buquoi’s left is Harvey Kline and on his right is Dave Gustin, both Monterey trained linguists and behind Gustin is Steve Shlafer, also a linguist. Schlafer later became a Buddhist monk for a time and lived briefly in a pagoda on the outskirts of Saigon, where he was during the Tet Offensive of 1968. Except for John, all of them were a class ahead of me at Monterey. John was in my class of 27 but in another nine-man section. He had arrived on September 11 and recalls that I was already there when he got to the 3rd. They had been ordered to the rifle range to update their weapons qualification, coincidentally on the day President Kennedy was killed. As a newly arrived unassigned soldier, I was not part of this group and remained behind in the Davis Station barracks, where I awoke to the news of the assassination. Stanley Karnow described this “karmic pivot” in similar, if somewhat less poetic terms. Americas responsibility for Diem’s death haunted U.S. leaders during the years ahead, prompting them to assume a larger burden in Vietnam.8

The overthrow and assassination of Ngo Dinh Diem and his brother Nhu affected those of us in the 3rd RRU in different ways. I fully accepted the US view that Diem’s dictatorial ways and alienation of the population had been an obstacle to effectively prosecuting the war, and I was deeply impressed by the ecstatic sense of deliverance in Saigon and the popular relief at the dissipation of the oppressive atmosphere of the last days of the Diem regime. I did get some glimpses of the underlying complexity of the Saigon reaction, which I had initially assumed was unqualified joy and relief. Soon after the coup, I climbed in a three wheel Lambretta on the base to go the main military gate. There were several ARVN Airborne soldiers jammed in with the rest of the passengers, resplendent in their distinctive red berets.

Saigon newspapers were lionizing the Airborne for their central role in the coup, calling them Thiên thần mũ đỏ (celestial heroes in the red berets). So I repeated this phrase, widely circulating in Saigon to the Airborne troops. Instead of the smiling acknowledgement of this praise, which I expected, the response was a glowering, reproachful stare. I interpreted this as a silent rebuke and a message that Americans had no business in intruding in a Vietnamese affair. It was an indelible lesson in the limitations of American bonhomie and easy assumption of shared interests and feelings, the power and complexity of Vietnamese nationalism, and the start of a process of progressive disillusionment about American assumptions that we knew what was best for Vietnamese.

Unknown to me until very recently, some of my fellow linguists had a quite different reaction from my euphoria, based on their front row seat as witnesses to the events of the coup. John Buquoi and some of his fellow linguists were monitoring the communications of the coup plotters who were providing each other updates about the search for Diem and his brother Nhu. John wrote me in an email on April 4, 2019 “The Diem coup was a helluva intro to ‘the mission’ and, as it turned out, I ended up monitoring Big Minh’s phone (among others) and actually heard the Sunday morning report of Diem and Nhu’s death…the quotes in the poem are direct quotes from the assassin’s mouth.”

Escalation

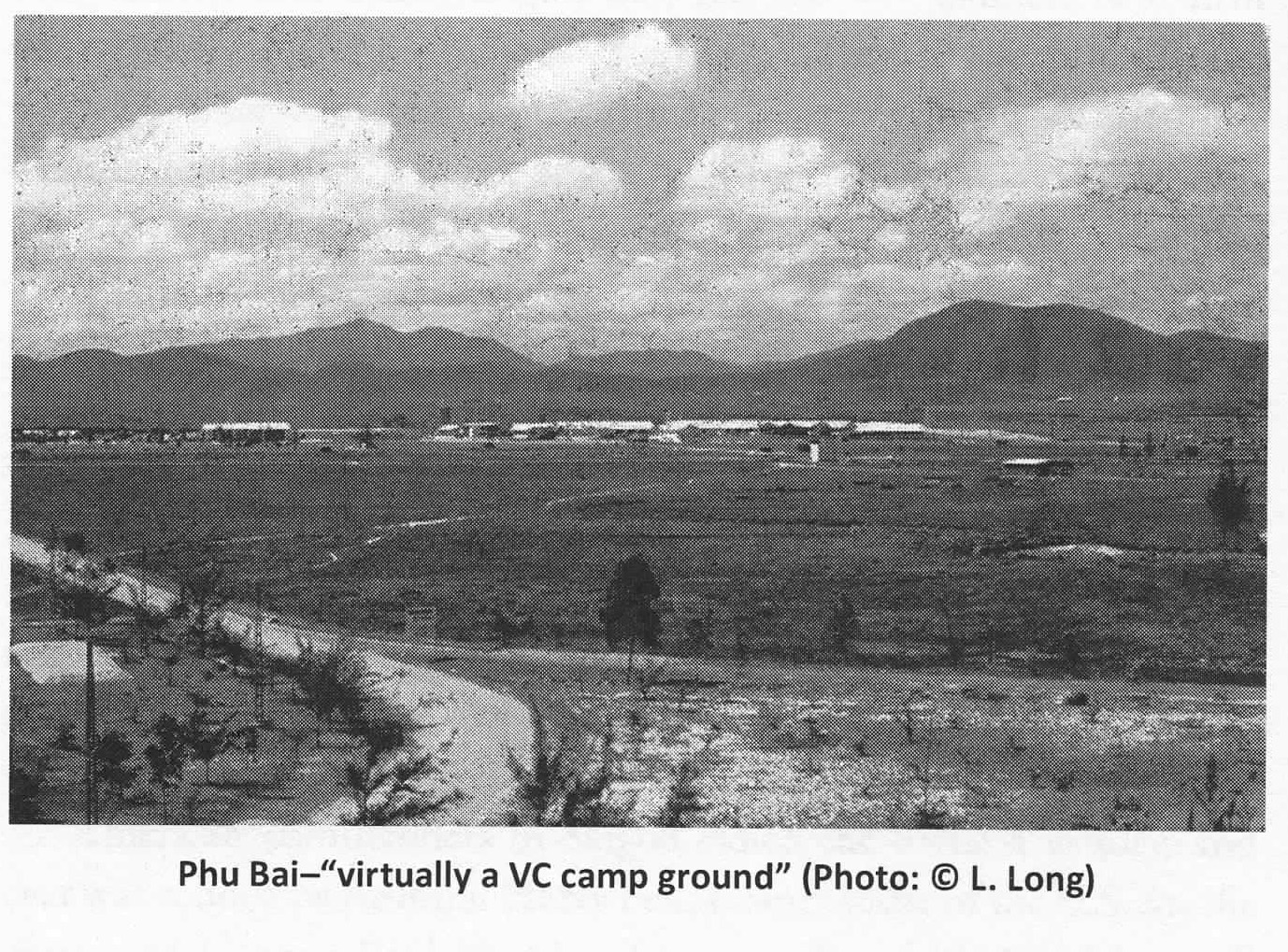

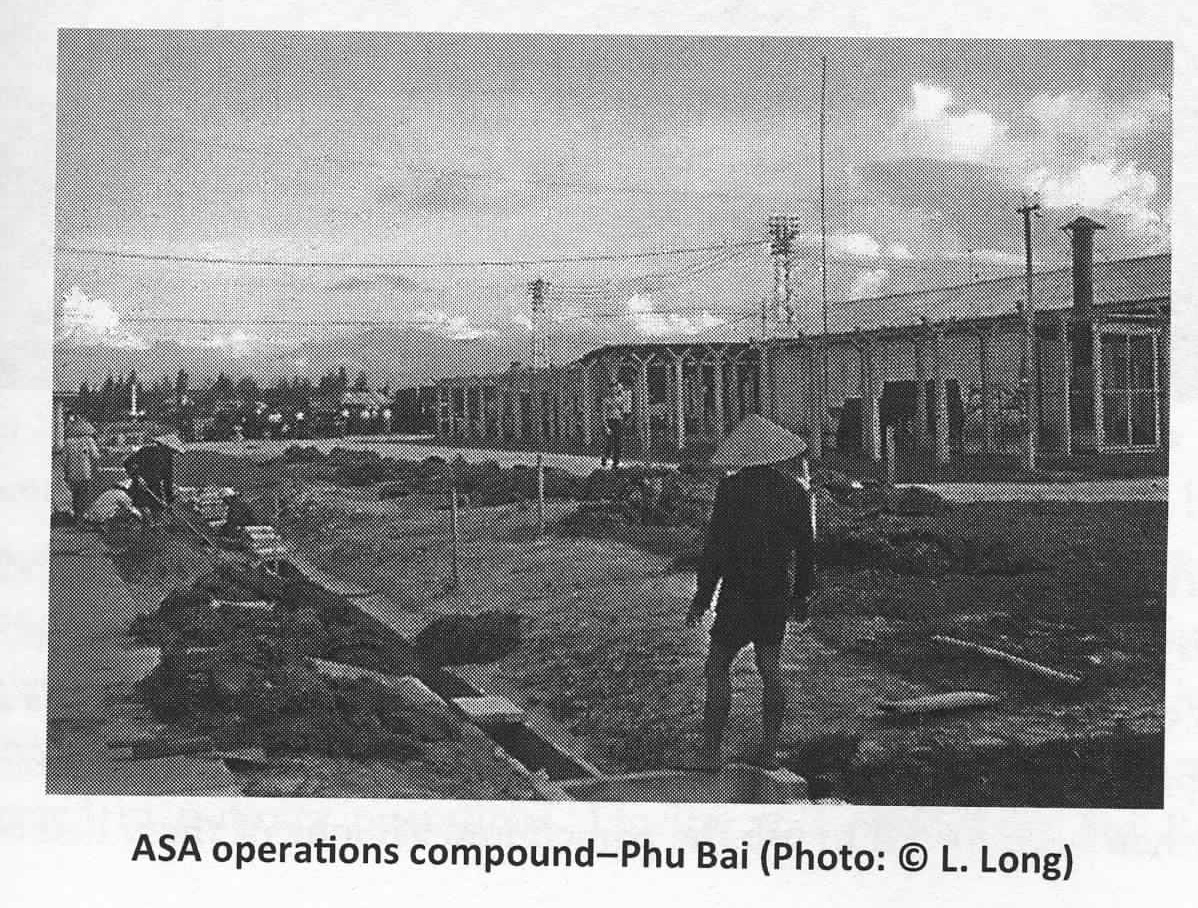

When I arrived in Vietnam in early September 1963 there were less than 16,000 American soldiers in country, collectively euphemistically called “advisors” to assert that, in conformity with the Geneva Accords, they were not directly involved in military combat. Though it did not directly engage in combat operations, the 3rd RRU was clearly not advising anyone.9 Its attempts to locate Viet Cong radio transmitters had resulted in casualties. Indeed Davis Station was named after Sp.4 James Davis, one of the earliest Americans killed in action in December 1961 while on such a ground operation.10 As the American military presence escalated, the 3rd RRU was supplemented by a new ASA unit called Detachment J (Det. J) and stationed in Phú Bài a small air base on the southern outskirts of the city of Hue in central Vietnam. Despite its proximity to Hue, the ARVN detachment in Phú Bài had been overrun by Viet Cong forces in January, 1963. The MACV report that decided on the placement of Det J had itself termed the area around Phú Bài “virtually a VC camp ground.”11

The value of the location was that it brought ASA’s surveillance capabilities closer to the fighting (and to North Vietnam, which it also monitored), but that also raised the dangers to Det. J. For the 3rd RRU , the expansion of Det. J provided a solution to the problem of what to do with me, a linguist with no available slot to fill in Saigon. So, in early 1964, I got orders to transfer to Det. J in Phú Bài.

At the time, I wasn’t aware of the earlier attack on Phú Bài, or the MACV “VC camp ground” designation, but I had heard that all members of Det. J were indefinitely confined to base because of the political agitation and anti-Americanism in Hue that had been triggered the previous year. A soldier stationed in Det. J wrote a letter to an ASA buddy in Taiwan dated 26 November 1964: “Yes, I’m in Vietnam and it’s hell. I’m in the northern part of the country outside of a town called Hue. I work straight days and train every night. … The VC haven’t bothered us yet, but frankly we expect to be hit before the first of the year. …There is absolutely nothing to do in town [Phú Bài] or on base and we cannot go out after 6:00 p.m. because the VC controls the area at night.”12

The idea of not only being separated from Mai, but isolated in a backwater encampment did not appeal to me. This new development accelerated our plans for marriage. I went to the 3rd RRU company commander to inform him of my intention to marry a Vietnamese national.

He was dumbfounded. I had only been in Vietnam a few months and was already contemplating marrying a local? The C.O. was sure that it must be a case of momentary infatuation with a bar girl. He didn’t need to remind me by marrying a foreign national that I would lose my cryptographic clearance (though I would retain my top secret clearance), and would be transferred out of the Army Security Agency (and, therefore, the 3rd RRU). I explained our situation, that Mai was a graduate of Georgetown University and that we had known each other for over two years. With reluctance he allowed the Army procedures for approving a marriage to be set in motion.

What followed was a real education about the constraints of citizenship and military regulations that most Americans never have to confront in their lifetimes despite all the complaints about government overreach. Combined with the Vietnamese government red tape, by the time we were finally married in a civil ceremony at the Deuxième Arrondissemont (Quận Nhì) we had been forced to jump through countless bureaucratic hoops. Mai has vividly described the tedium and frustration of this process in her book. I was outraged that the Army had arrogated the right to intervene in one of the most important decisions an individual can make. I accepted that the duty of a citizen was to pay taxes and be drafted and, if the government so chose, sent off as cannon fodder, but I emphatically did not agree that it could dictate whom I could or could not spend my life with. I fleetingly considered the possibility of renouncing my citizenship in protest, but the thought passed as quickly as it had come.

I didn’t learn of the crowning absurdity of the process until many years later when Mai mentioned it in her memoir. She was called in for a counseling session with a military chaplain – something I also thought was a governmental overreach, since the army was using the cloak of religion to disguise its methods of obstructing marriages of service personnel which it felt were inconvenient to the army’s mission. But when I learned much later what the chaplain had actually said to Mai, I must admit I found it uproariously amusing. He knew all about the perils of mixed marriages, he advised her. “I myself am married to a Norwegian!” (E.g. an American of Norwegian descent, who were looked down on by the Swedish-Americans like the chaplain). No comedian could make this up! It was a perfect example of the Freudian concept of the narcissism of small differences. I don’t mean to make light of the seriousness of the issue of inter-racial marriage at that time. Although I didn’t know it then, until the Supreme Court struck down Virginia’s anti-miscegenation law in the case of Loving v. Virginia in 1967, inter-racial marriage was a felony in my own home state.

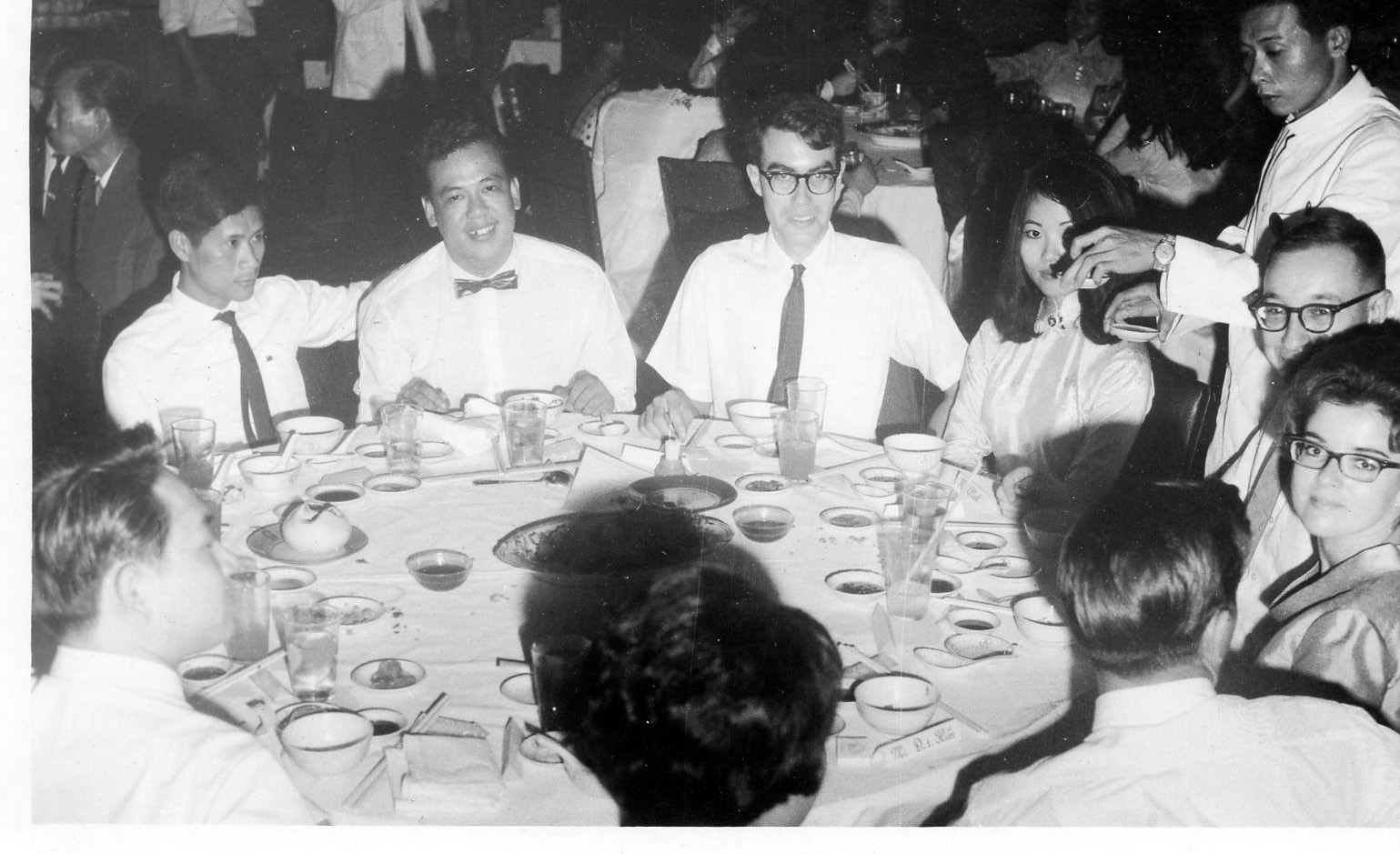

Eventually the army ran out of delaying tactics and gave the necessary approval. So, accompanied by Mai’s father and two Vietnamese witnesses from my new workplace, the Translation Section of J-2 MACV, and a consular official from the U.S. Embassy to witness the event and provide the official certification of the marriage, we were wed on March 3, 1964. Despite the fact that I indicated that I spoke Vietnamese, the Saigon city official insisted on conducting the ceremony in French, the only proper language for dealing with foreigners in the eyes of the Vietnamese civil service, who had been formed in service to the colonial regime. The consular official somewhat sheepishly passed on request from CBS television to include us in a short piece that it was doing on “war brides” in Vietnam, but he readily agreed with my response that this was an invasion of privacy.

In addition, I thought it insulting to include Mai in the “war bride” category along with the bar girls who constituted the largest number of Vietnamese marrying Americans in 1964. It was bad enough that walking down the street in Saigon together, the automatic assumption of the passers-by was that any mixed couple could only be a GI with a bar girl. Eventually we became resigned to the inevitable comments “Mỹ với đĩ” (“there goes the American with the prostitute”) and even, in time, began to find them amusing, and turned them into a shared private joke. Every time we passed another mixed couple I hummed the melodic line that followed the contours of the Vietnamese tones of Mỹ với đĩ. In the absence of the words, only Mai knew what this tune meant. Nonetheless, the inevitable perception of any mixed couple on the streets made us keep our public appearances together to a minimum, and ruled out any public display of affection. The disparaging commentary was ubiquitous – but sometime amusing. Once on a very hot mid-day, Mai and I were walking from our apartment on Hai Ba Trung to her college room mate’s nearby house on Yen Do. There was no traffic on the street and only one other living soul out in the mid-day sun, a kid who was probably nine or ten years old. As we passed, he continued to squat down and play some game in the street. Without looking up he muttered “Năm trăm đồng một cú” so softly I had to ask Mai to repeat what he had said. She told me. It translates to “500 piasters a shot.” That was about five US dollars at the black market rate, but obviously a formidable sum in the view of this kid. Mai was not amused, but I told her she should be flattered at the knowledgeable evaluation, which put her in the poule de luxe class.

Tet flower market on Nguyen Hue street February 1964.

Mai has described the negative reactions of her relatives to our impending marriage, leading some of the clan elders to threaten a boycott of the wedding reception which would officially launch us as a married couple in Vietnamese society. In the end, curiosity got the better of them and the reception at the Dong Khanh restaurant in Cho Lon was well attended by members of her extended family. Some of her American-educated Vietnamese friends were also there for moral support.

Mai’s father carefully coached me in delivering a flowery toast to the assembled relatives in the Vietnamese equivalent of King James English. Somehow I managed to deliver the appropriate Sino-Vietnamese sentiments. “We, your niece and nephew, beg to thank you, the venerable elders for coming to witness our wedding today. This gives us happiness and great fortune….” (“Chúng cháu xin cảm tạ các cụ đã đến chứng kiến đám cưới của chúng cháu ngày hôm nay. Như vậy là hạnh phúc cho chúng cháu lắm….” Mai’s father’s coaching produced the desired effect, and the wedding turned out to be a great success – despite our unprepossessing arrival at the restaurant in a humble blue and white taxi which, to Mai’s chagrin, looked “like a frog on wheels” rather than the customary rented oversized rented 1950s vintage American car with chrome and fins.

Dong Khanh Restaurant and Hotel 2018

Mai, David, Mai’s Father and clan relatives at wedding reception 1964.

After I had informed the 3rd RRU of my plans, I was in limbo for over a month. The 3rd RRU shopped me around to various US military units but, astoundingly, no one seemed to have any use for a soldier fluent in the Vietnamese language. Perhaps this was an early indicator of the scant regard the US government had for equipping itself to hear and understand the Vietnamese point of view. I moved from Davis Station to a downtown hotel to await further assignment. The Metropole Hotel was conveniently located, but given the number of transient soldiers who kept odd and irregular hours the shades in the rooms were always closed. The frigid air conditioning was an initial relief, but eventually combined with the dark gloom to provide an environment that was totally isolated from its surroundings – which further contributed to my sense of isolation as I awaited a determination about my future. The centrality of the Metropole also made it an attractive target for terrorist attack. In December 1965 a truck bomb exploded outside the hotel, killing 175 people, including 72 Americans. By that time, fortunately, I had moved out. I was also gone from the 3rd RRU by the time two of its members were killed by a bomb at a nearby field while playing softball.13

Bomb damage at Metropole Hotel, December 4, 1965.

If you were to try to find the traces of the Metropole today, this is what you would see.

Hotel Pullman, Saigon, 2016

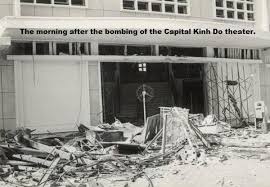

Saigon in 1964 and 1965 was the target of a number of terrorist bombings of buildings. One of the first was in February 1964, when a massive explosion demolished large parts of the Kinh Đô movie theater. Three Americans were killed and 34 wounded. Jim Potratz, who would soon be my boss in the MACV Translation Section was there with his young son. Jim recalls that “I went with my oldest son then 4 years old. I sat way in front with him on my lap when I heard the three or four shots, turned around and the doors blew in. After a few minutes we exited by the side doors. Two weeks later, the MR-4 [Viet Cong Military Region 4, which included Saigon] staff assistant was captured carrying the after action report on the Kinh Đô — it described how they came (taxi controlled by them), one guy got out, shot the MP (kid from Milwaukee), and put the package (10 kilos?) inside the door and fled. Explosion killed 4-5 and wounded more than 50 (almost all from the air cons tacked up under the balcony).”14

I was soon to meet Jim Potratz, who had fortunately survived the Kinh Đô bombing and would be my new boss. Finally, the 3rd RRU negotiated my transfer to the Translation Section of J-2 MACV, the military intelligence branch of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) which had been established in February 1962 as part of the Kennedy escalation of American military involvement in Vietnam. We moved into a small second floor apartment rented from a Chinese-Vietnamese landlord, not far from the Tân Định market on Hai Bà Trưng street.

Apartment complex at 423 Hai Bà Trưng 2016. This was our first “home” in 1964. Our apartment is on the second story above the awning.

The one bedroom apartment on the second floor had only enough room for a small table, and a kitchen which overlooked the back alley. It was Spartan living, but it was our first home.

We didn’t expect to receive any visitors in our cramped apartment in a run-down section of Saigon, but one day I heard a knock at the door. When I opened it I saw two striking young Vietnamese women, about Mai’s age, in glamorous ao dais. One of them introduced herself as Đặng Tuyết Mai. She wanted to see Mai she said. When Mai appeared to invite her in, she immediately recognized the future Mrs. Nguyen Cao Ky, well known in Saigon as a great beauty, who was regarded as a trend-setter in her upscale – as it was then regarded – job as an Air Vietnam Hôtesse de l’air or flight attendant.

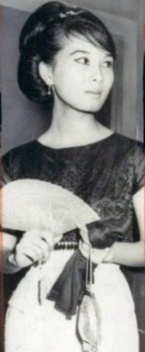

Đặng Tuyết Mai, soon to be Mrs. Nguyen Cao Ky, invited Mai to join her in a Saigon fashion show. 15 On right is a photo of Mr. Mrs. Ky ca 1966

Tuyết Mai and her friend said they had heard that Mai was one of the great beauties of Saigon, and invited her to join them in an upcoming fashion show. Mai was flattered by the recognition but, to her everlasting regret, turned them down.

Our second floor apartment, it turned out, was easy pickings for Saigon’s highly skilled “second story men.” One night Mai awoke from a deep sleep with the odd feeling that there was something amiss. There was a Saigon urban legend that burglars often used “knock-out medicine” ( thuốc mê ) – whether in powder form or as some kind of spray is not clear – in order to essentially anesthetize their victims so they can work undetected. I doubt this was the case – Mai had been awakened by mosquitoes who had come in through the screen door which she noticed was open. As we got up to investigate, a shadowy figure bolted across the room, through the screen door to the rear balcony and, in a flash, lowered himself down to the back courtyard of the apartment complex on the drain pipe he had used to climb up – obviously someone who knew the neighborhood well. I immediately discovered that he had rifled through my pants and fled with the pants and my wallet. I rushed to the window and yelled down at the fleeing figure “trộm!” [burgler]. There was, however, no one around to hear, let along do anything, and after he had run a safe distance, he paused. I still remember his silhouette backlit by a lone street light as he momentarily froze in a scarecrow-in-the-field posture while he contemplated his next move before disappearing down an alley. Mai later found my pants and wallet on the street (minus the small amount of cash taken by the burglar).

Our second floor apartment, 423 Hai Ba Trung in 1964

The only other time in Vietnam I was the victim of petty crime was around this time. As I was walking along the sidewalk on a block of Le Loi street where a string of used bookstores were set up side by side, covered by awnings that created a kind of long tunnel. Jammed in among a tightly-packed crowd, I felt a tug at my shirt pocket, and saw that someone had grabbed my case with prescription sun-glasses and was trying to flee through the crowd. Amazingly, he did not get far. A small group of students who were outraged by the spectacle of bad behavior and the shame they felt about the bad image of Vietnamese this act of thievery would create, grabbed the thief, confiscated his loot, and returned it to me without comment, after giving the thief a sharp reprimand. I thanked them profusely but they unsmilingly waved it off and went on their way. They were doing it to uphold their own standards of acceptable behavior, was the message, and not to please an American. I understood the sentiment but at this period of widespread anti-Americanism, especially among students, I was surprised and touched at their intervention. They could have simply let it go and taken satisfaction that the American got what he deserved, which is what the Vietnamese cop described below would have done.

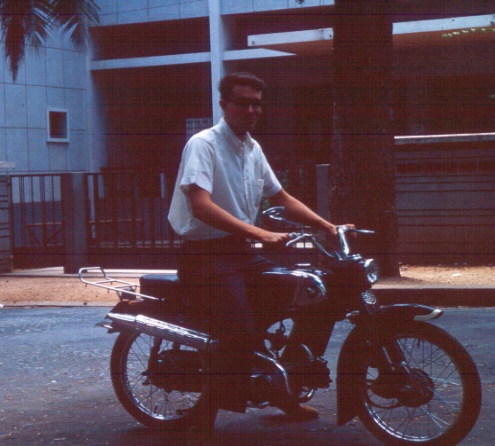

I eventually bought a Honda motorcycle to commute to the Tax Building in central Saigon, where I had taken up my new job at the Translation Section of J-2 MACV.

I had learned through the grapevine that a Military Policeman about to rotate back to the US wanted to sell his Honda 90 motorbike. So I took a blue and white cab five kilometers across town to the MP barracks in Cholon and purchased the bike. This was in an era when Hondas were an extreme rarity. People visiting Vietnam today experiencing the wall-to-wall motorbikes throughout the country might be astonished to know that there were, at most, a few hundred Hondas in Saigon in 1964, most owned by Americans, since Vietnamese were forbidden to buy them to conserve scarce foreign exchange, and had to be content with the motorized bicycle (moped or “mobylette”) which was the high status vehicle at the time. I would guess that there were no more than 100 such Hondas in Saigon when I purchased mine.

After a cursory five minutes of instructions on the gearshift, I wobbled off on my ride back across town. I had never ridden a motorcycle before and the challenge of coordinating balance with shifting gears and handling the brakes while negotiating chaotic Saigon traffic was formidable. Nevertheless, I made shaky progress until I reached the Scylla and Charybdis of Saigon traffic, the feared Ngã Sáu intersection through which most cross-town traffic had to pass. The following video clip provides a rough approximation of mad chaos that prevailed at this roundabout into which six of the major streets in Saigon fed. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mr5Gssaxl6g It was a roundabout that seemed to be designed by the Three Stooges for comedic effect. There were no right of way rules and every vehicle seemed to be headed across the flow of traffic (such as it was) at different angles.

After I had managed to enter the Ngã Sáu and had traveled about a quarter of the circumference, I had to escape the circular flow to make a turn, exiting the roundabout onto Hồng Thập Tự (the current Xô Việt Nghệ Tĩnh) I saw a young man slowly and unsteadily coming toward me an a bicycle, carrying an elderly man – probably his father – on the handlebars. He was unable either to stop or, evidently, to avoid me and ran into my rear tire, toppling to the ground in the process. I managed to remain upright and stopped my Honda right in the middle of the sea of swirling traffic.

Despite the traffic, a crowd quickly formed around the accident scene comprised mostly of people who were themselves on bicycles. The young man on the bicycle was loudly proclaiming that he had been grievously injured despite the fact that he and his father were unscathed because they were almost at a standstill when they ran into me. The crowd came to his support, but I said (in Vietnamese) “if you and your father are seriously injured we must get you to a hospital right away.” This gave the young man pause. He didn’t want (or need) to go to a hospital. He wanted a cash settlement from me. The Greek chorus of a crowd however, had muttered its collective approval. “Yes, get them to a hospital quickly.” The situation, which had been heading south for me, briefly froze as a result of my offer to take them to a hospital.

This incident happened at a time of great political tension and rising anti-Americanism. Moreover, the Honda itself was an emblem of American treaty-port privilege, since Vietnamese could not buy them. The fact that I was dealing with the situation in Vietnamese bought some time for what might have escalated into an ugly confrontation. Soon a “white mouse” policeman (e.g. an ordinary cop on the beat, known for their white uniforms) appeared on the scene. After some conversation, punctuated by the “victim’s” demand for compensation, it became clear that I was the one who had been run into, rather than the reverse. What followed was my first introduction to the counterpart of “situational ethics” – “situational law enforcement.” The cop acknowledged that I was the one who had been run into, but said (I can no longer remember the exact words) “Come on – you’re a rich American. Just give them some money and we’ll call it square.” Which is what happened. I am sure in advising me to pay up and get on with it, the cop used what became my favorite Vietnamese phrase “làm cho xong chuyện” – just do it to get it over with. I appeared at the police station the following day and handed over a small (“solatium” or consolation) payment and we all went our respective ways. I guess I was fortunate to avoid an ugly mob scene in this time of rising anti-foreignism, and to make it safely the rest of the way home on my prized Honda. Needless to say I did not risk riding it to the police station the next day, and took a cab instead.

New Assignment – the MACV Translation Section

By this time I had emerged from limbo and had taken on a new assignment at the Translation Section of J-2 MACV. MACV was a proto-command headquarters, whose very existence implied that American combat units would eventually follow and which would supersede and subsume the modest Military Advisory and Assistance Group (MAAG). Unlike MAAG, MACV was a command headquarters which would be capable of directing American combat troops, should they be sent to Vietnam. Its establishment was a critical step in the escalation toward direct military involvement in the conflict. This was the primary reason that the Soviet Union and China, who had been uninterested in Vietnam until early 1962 when MACV was established, and they suddenly turned their attention to what had been, until then, a side-show of the Cold War.

MACV’s first headquarters didn’t have the appearance of a military command. It was on a leafy street in a residential area of Saigon.

MACV Headquarters 147 Pasteur Street, circa 1963.

Because the entire command headquarters had to be housed in a converted residential villa, space was at a premium. So the Translation Section which belonged to MACV J-2 (“J” indicates a command branch – operations, intelligence, logistics etc. above division level and “2” was the traditional designation of the intelligence branch) was established on the top floor of the Tax Building, a commercial arcade in the center of downtown Saigon.

Tax Building, corner of Le Loi and Nguyen Hue, 195os.

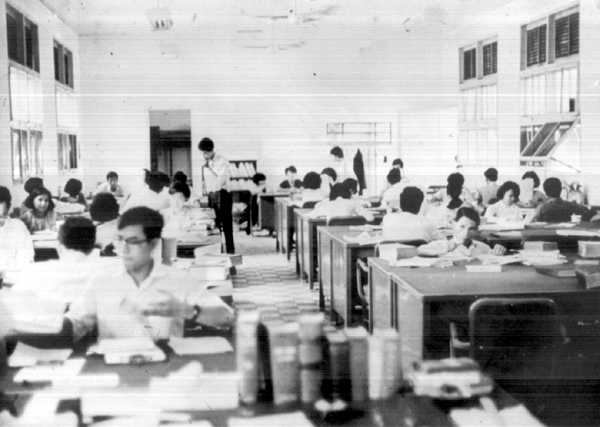

When I arrived there in early 1964, the operation of translating captured Viet Cong documents was housed in a complex of two large rooms in the back part of the top floor of the commercial arcade known as the Tax Building. Jim Potratz, who as an E-6 or sergeant on his second tour of duty in the Army was in charge, and the only other American there.

Jim Potratz and Bryan Elliott in My Tho restaurant 2018. When we met for the first time in over 50 years, Jim looked at Bryan and said “I recognize this guy, but not you,” referring to the fact that in 1965 I had my son’s silhouette but had gained nearly a hundred pounds in the interval.

In a 2016 email Jim provided some recollections of the early years of the translation section. “MACV was formed in Jan 1962. I presume the translation section was created months later. As far as I know the first chief was an Army captain who graduated from ALS (Army Language School) a couple of classes before me (circa March 1962), and left the translation section in February-March-April 1963. He didn’t want the job but was forced into it. I think Tax building was the first location. A couple of other oddball MACV sections were there with us but left. … It was formed with a local staff of six translators and two typists. The US side had an O-3 slot for chief plus one enlisted slot. Later additions like you and [Gale Halvorsen] were not in slots.” So, in a sense, I was still a transient without an official slot in the Army’s TOE [ The Table of Organization and Equipment]. The TOE is a document that prescribes the wartime mission, capabilities, organizational structure, and mission essential personnel and equipment requirements for military units.

In the chaotic transition year of 1964, however, the lack of a formal position for me was overlooked because J-2 was desperate to find people who could help the overstretched Translation Section function. At a time when the Army had few independent intelligence sources (apart from the signals intelligence of the Army Security Agency and its own modest network of military advisors reporting on what was happening in their areas) captured documents provided a valuable and unique insight into Viet Cong operations and intentions. But in order to make them useful for intelligence analysis, they had to be translated. My job was to help Jim Potratz oversee and edit the translations for accuracy and readability.

In this sense, the Translation Section constituted a bottle neck constricting the flow of vital intelligence from the field to the headquarters analysts at J-2 MACV. The original six translators and two typists simply couldn’t keep up with the rapidly escalating demands for analyzable documents. Thus there was pressure for some modest growth in numbers, but by the end of 1964 the number of Vietnamese translators never exceeded a dozen, and the number of Americans overseeing the translations was never greater than three – all enlisted men.

Naturally the direct American intervention caused a dramatic expansion of the Translation Section, which moved to a new building near the airport in October 1966 to house the dozens of Vietnamese translators. Rather than a backwater overseen by a lowly E-6, By this time it was commanded by a Lt. Col., processing millions of documents a year.

Vietnamese translators in their new office near Tan Son Nhut, J-2 MACV, circa 1966 http://webdoc.sub.gwdg.de/ebook/p/2005/CMH_2/www.army.mil/cmh-pg/books/vietnam/mi/ch02.htm

Translation section employees give a farewell dinner for Mai and me. Trần Văn Nhơn is to my right. The Morells are to Mai’s left

During most of 1964, however, we were largely left to our own devices, because our nominal superiors realized that they knew nothing about how to run a translation operation, and were satisfied to leave us alone as long as we produced. In fact, they further recognized that trying to impose standard army discipline on us would probably reduce our effort to a lowest common denominator of military mediocrity and throttle the flow of documents to them. Not being in a regular military unit, we were spared much of the scut work of enlisted military life – KP, inspections, etc. Our only duty along these lines was periodically bagging up the classified trash generated by our very substantial volume of translated and mimeographed documents, and taking it to a nearby ARVN base to burn – a task that, like overseeing Vietnamese painters at the 3rd RRU, could not be delegated to anyone without a high security clearance.

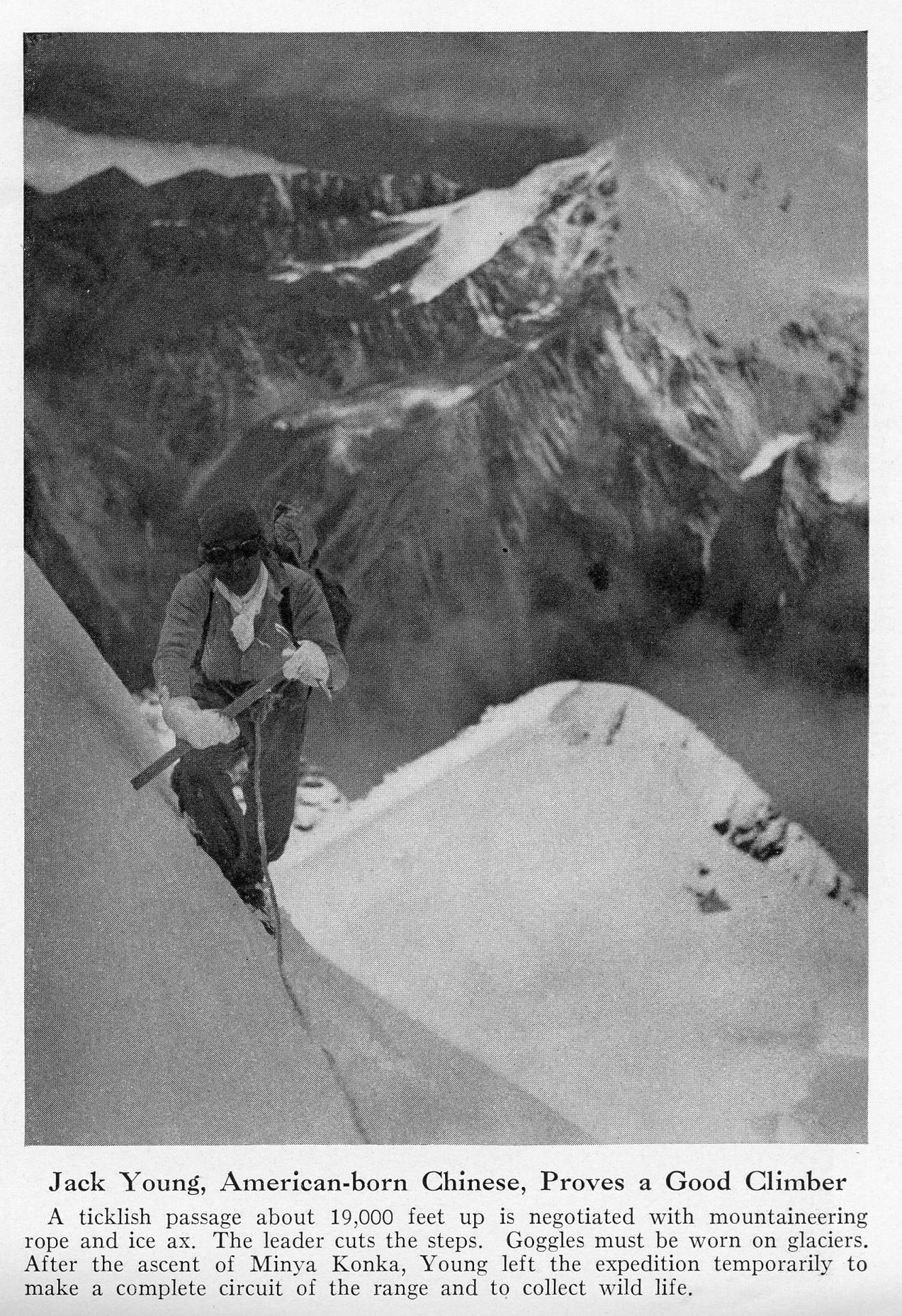

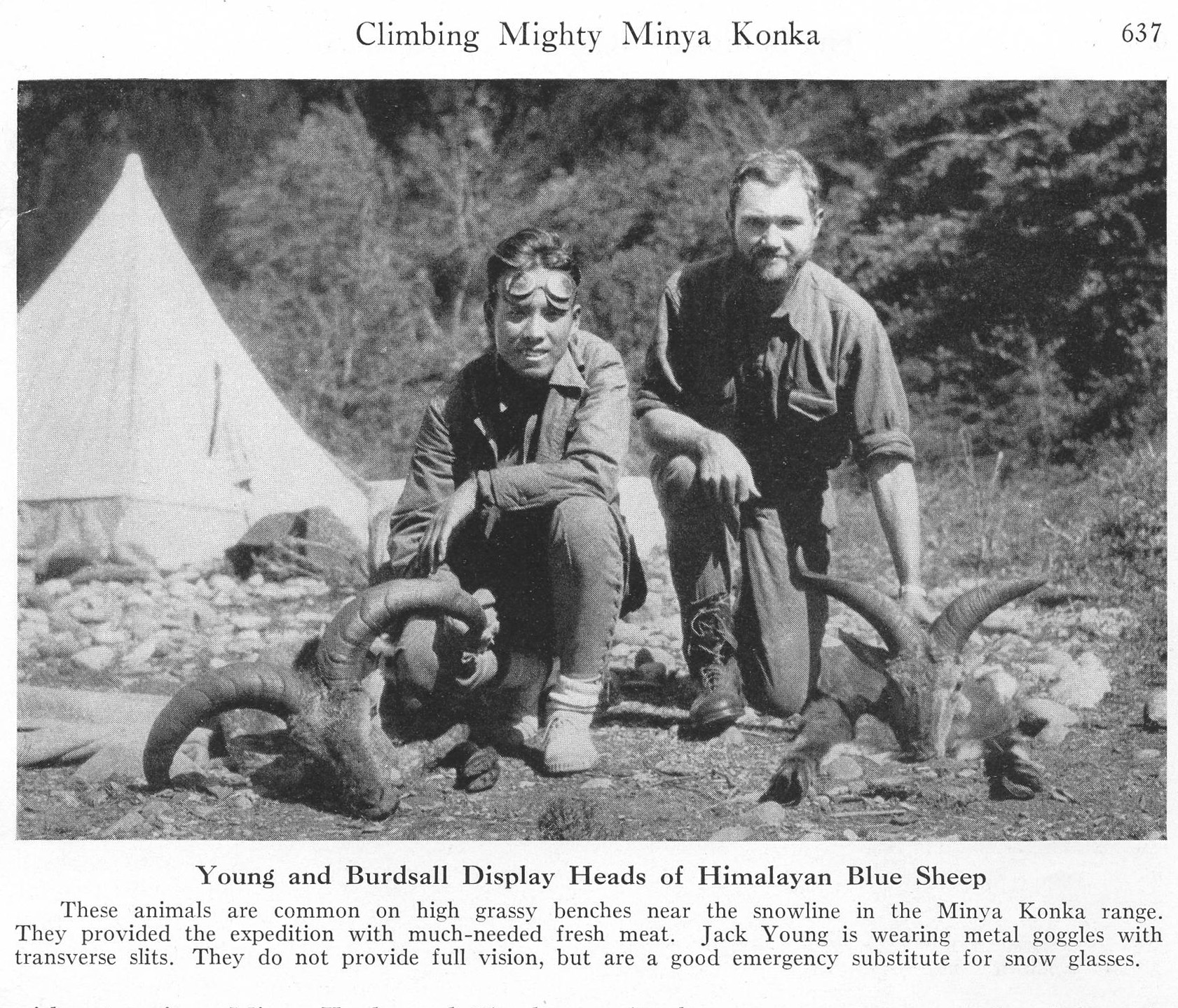

The overall commander of the Translation Section was the head of the Collections Branch of J-2, the inimitable Col. Jack T. Young, one of the most arresting personalities I have encountered in my eighty years. At the time Col. Young was reputed to be the highest ranking Asian-American officer in the Army. His military background was remarkable and unconventional. Born in Hawaii and a fluent English speaker, he also retained his fluency in Mandarin Chinese, as we sometimes had occasion to witness. In his youth, Jack Young had returned to China to take part in the exciting and turbulent events of the 1930s.

Like his brother Quentin, Jack was a professional guide and explorer. Quentin secured the first panda to be brought to the United States for society grand dame Ruth Harkness. Jack led a mountaineering expedition which scaled Minya Konka, and accompanied Kermit Roosevelt on his adventures in China.

Jack Young in 1935

A 1990 article on the two Young brothers wrote: “Though [Quentin] Young was 22 at the time, he and his brother Jack, then 26, were among the more experienced naturalists in China, and they traveled through time and cultures. They were college educated ethnic Chinese, but their family had spent two generations in America — Jack was born in Hawaii — so they were neither Americans nor Chinese, yet both at once, ‘people adrift,’ as Jack says.”16

“Following the practical habit of the day, they chose English names to ease communication with English-speaking imperialists, who could not or would not deal with their Chinese names. Tai Jack became Jack Theodore and Ti-Lin became Quentin, both out of admiration for the Roosevelt family, whom Jack knew well. Their grandfather changed the spelling of the family name Yang to Young; coming from English lips, it was closer to the Chinese pronunciation and less grating to Chinese ears.”

“The brothers were dashingly handsome in their youth, a head taller than their Chinese contemporaries, wearing generous black pompadours combed straight back and well-tailored, modern suits over athletic bodies. Though they were sophisticated men living in Shanghai and New York, they moved easily into the Dark Ages of rural China of the 1930s. The sepia-tinged snapshots in Quentin’s photo albums depict village magistrates, warlords in full costume, a princess from a tiny kingdom called Kantze Sikong, vultures tearing apart human corpses in Tibetan funeral pyres, half-naked Lolo slave girls assigned to serve them, bandits he and Jack captured and delivered in chains to local authorities.”

Jack with magistrate in Sikong, 1935 on right National Geographic May 1943

National Geographic, May 1943, p. 637.

“The Youngs were an enigma to the Tibetans and Lolo tribesmen who, as a matter of pride and profession, took advantage of foreigners and ‘downriver’ Chinese. ‘They didn’t know what to do with us,’ says Quentin. ‘We didn’t look like Americans, but we knew the ‘foreign devils’ language. We ate what the foreigners ate, but what they did too — rice, salt fish, tofu.’ Uncertain and intimidated, the locals helped them collect, shoot, or capture giant pandas, golden monkeys, takin, rare Chinese pheasants, and Tibetan flora for American museums or private collectors.”17

Jack’s resourcefulness and quick wit saved the expedition to Minya Konka, a 23,000 foot high mountain on the border between China and Tibet, when they were initially blocked by locals from their endeavor on the grounds that a previous explorer had brought bad luck. The leader of the expedition recalled, “Jack Young’s diplomacy now stood us in good stead. He told them that we had crossed the great water and made a pilgrimage of a whole year to visit this object of our veneration. With this plea and small contributions for prayers and the burning of incense, he finally reconciled them to our going>”18….Today, despite their age — Quentin is 76 and Jack is 80 [in 1990]— they are still big and little brother, much to their frustration, still as hotheaded as in their youth. In 1934, while crossing a high Tibetan mountain pass in a blizzard, they argued so bitterly that they pulled guns on each other and would have shot if Jack’s first wife, Su Lin, for whom the panda was later named, hadn’t thrown herself between them.”19

A lengthy 1990 profile of Jack Young and his brother Quentin in the San Diego Reader recounts Jack’s remarkable life as a game hunter and adventurer. “….Quentin Young ceased to be an explorer and naturalist when the Japanese invaded China a few months after Harkness’s departure, and he reluctantly followed his older brother Jack into a career of espionage. And so in the end, the story ceased to be a fairy tale and turned modern, more like a tragic, improbable television miniseries script, full of spies and bandits and historical figures.”20

In view of the clear exaggerations of his role in Vietnam, one must be somewhat cautious in taking all of this oral history at face value – though the China and Korea parts can be independently confirmed.21 The article continues “In 1953, Jack Young was stationed with the U.S. Military Advisory Group to Chiang Kai-shek, and it was the first the brothers had seen each other since the late 1930s. Quentin has a photo that marks the occasion, Jack in his major’s uniform, Quentin smartly turned out in a sport coat and trousers, astride a see-saw in a playground.”

“Jack had risen to the rank of major general in the Chinese Army but was drafted into the U.S. Army after Pearl Harbor and made a second lieutenant. He claims that he served briefly as an aide to General Joseph Stilwell, who headed the American military presence in the China Theater. (Barbara Tuchman in her biography of Stilwell mentions a young captain named Dick Young, a Hawaiian-born Chinese in Stilwell’s office, perhaps a mistaken reference to Jack.) He asked to be transferred because of Stilwell’s racism. One day in Jack’s presence, Stilwell muttered how ‘these Chinamen can’t do anything right.’ Suddenly realizing Jack was there, he said, ‘Oh, but you’re different.’ Jack replied, ‘No, I just speak English.’ So Jack went behind Japanese lines as an intelligence officer, establishing safe houses and planning escape routes for downed Allied pilots. His wife claims to have heard him mentioned in a radio broadcast by Tokyo Rose — journalists came to interview her as ‘the girl left behind.’”

“During the Communist Revolution in China, he worked as an aide and interpreter to General George Marshall and also as go-between for Chou Enlai and Mao Zedong, Marshall, and Chiang, which required him to live with Mao and Chou in a cave in ‘Yenan. Jack also befriended Yeh Chien-ying, a principal Communist Army general. Yeh turned to Jack for help when his daughter was arrested by Chiang’s police. Jack intervened with Marshall and had an American plane pick her up and spirit her away.”

The connection with Yeh Chien-ying (Ye Jianying) can be verified by my personal observation. Col. Young rarely came to our offices in the Tax Building, but one day he swept in unannounced. He cut a commanding figure in his tropical dress shorts and dramatic presence. Jim and I leaped to attention, and Col. Young proceeded to inspect the work of the office. Coming to the desk of one translator, it turned out he was working on a report from Hanoi about the visit of Ye Jianying – an important indicator of Chinese support for North Vietnam. The translator was stumped about how to render the Vietnamese rendition of his name (Đào Diệp Anh) into the then-standard Wade-Giles English phonetics. Without skipping a beat, Col. Young whipped out his wallet and extracted a photo which had a Chinese inscription (verified by the translator who could read Chinese – no doubt the characters were Col. Young’s Chinese name 楊帝澤) “Best Wishes to my good friend Jack Young.” I was floored at this connection between Col. Young and one of Mao Zedong’s closest associates and, of course, had no idea what the background of this remarkable photo was until much later. Of course this dramatic display of the photograph was of little help to the translator trying to find the right Wade-Giles transliteration, but it made a deep impression on all of us.

The San Diego newspaper profile continues: “In Korea, Jack led an unconventional warfare force with a division of Rangers, South Koreans, and turncoat North Koreans. He trained his troops in unconventional warware.

MAJ Jack T. Young, 2nd ID Ivanhoe Security Force commander, demonstrates silent kill, close combat techniques to ROKA students. 1st Ranger Company SGT Robert W. Morgan (tee shirt) is behind Young. https://arsof-history.org/articles/v9n1_culture_language_page_1.html

Jack led the first US recon unit into Pyongyang

Major Jack Young https://arsof-history.org/articles/v9n1_culture_language_page_1.html

Jack’s ingenuity and language skills in the Korean War are vividly described by Charles H. Briscoe https://arsof-history.org/articles/v9n1_culture_language_page_1.html[2]

His presence in Korea did not go unnoticed by the Communist Chinese, who arrested his parents, then broadcast an open radio message to Jack, stating they would be released if Jack defected to the Communist side. Jack’s mother wrote to him, describing how his father hid behind a trap door in the attic but surrendered to the police when they started to beat her. They took him away with a rope around his neck. Anticipating her own arrest, she signed the letter “your mother’s last command written under the light of the candle.” Jack keeps the letter framed on the wall of his study. On the facing wall is a framed letter from Mao, its characters big and messy in comparison with his mother’s fine and orderly hand.”

“Jack attempted to exchange the Communist officers for his parents, though he had no authority to do so. ‘I had lots of prisoners I didn’t even turn in,’ he says with a toss of the hand. ‘Don’t forget, I am an unconventional force, not bound by rules.’ But the deal did not go through, nor did a personal appeal to his friend General Yeh. Jack and Quentin’s parents starved to death in prison in 1952.”

“Jack met his current wife June, a Pentagon military historian, in 1954 in Quemoy; they were married in 1956. In the early 1960s, Jack went to Vietnam for two years as an intelligence officer, still operating behind lines. (‘I had a hell of a time convincing them that I am no gook,’ he says of that duty.) He retired from the Army as a full colonel in 1971. He had earned two Silver Stars, three Bronze Stars, and three Legion of Merit medals. He pondered returning to Vietnam to earn his general’s star, but Quentin talked him out of it. “You are getting old,” he told him, “and things are not good over there. Is it worth it if all that returns with a general’s rank is your name?”

The canard about “operating behind enemy lines” makes one wonder how much credit to give the rest of the life story of this flamboyant man although, as we have seen, most of it can be independently verified. Jack rarely left his MACV office except to go to Cholon to mine his Chinese contacts there for tidbits of information in order to reinforce the story he told his superiors that he was the best positioned to understand the Chinese role in Vietnam.

I made my bones with Col. Young when he called me in one day to solve a problem that required local knowledge. He had a dinner appointment in Cholon that evening at a restaurant-night club. He could not recall anything more than that it had an exotic non-Vietnamese name. Given Col. Young’s extreme sensitivity to one-upmanship, it would have been an unacceptable loss of face to have to go back to his host with the admission that he had forgotten the venue. Fortunately, I was somewhat familiar with the nightclub circuit, thanks to Mai, and I immediately guessed, correctly, that it was the Arc-en-ciel. This put me in his good graces for the rest of my tour.

Jack Young’s stories about Chinese in Vietnam no doubt met a receptive audience, since it was an article of faith among the American military that it was the Chinese who were behind the Viet Cong and their allies in Hanoi. In fact he would occasionally create a stir, as I witnessed once on a visit to MACV headquarters by reporting that his Chinese sources had a confirmed sighting of a People’s Liberation Army officer taking an active role in the insurgency in Central Vietnam. Of course, nothing ever came of it.

I witnessed one of his staged performances collecting intelligence on China’s role. One day he told me to stick around the Translation Section office after everyone else was gone. I was on tap for a job which he thought might require my undeserved reputation as an expert on Saigon as a result of the Arc-en-ciel episode. He would require my language skills to verify any Vietnamese personal or place names which might crop up in conversation with the Chinese informant from Cholon who he was going to meet, using the Tax Building office as a safe house for the rendez-vous. So I stationed myself in the darkened inner room and waited for the informant to arrive. When he did, I could not see the interaction, but I could hear the transformation of Jack Young from an imperious American colonel barking out crisp orders, to something which was almost a caricature of the devious Oriental, with a hissing intake of breath preceding every menacing sentence he directed at his interlocutor. It was great theater, but I doubt if anything came of it. My presence, in any event, proved superfluous.

Despite his tendency to exaggerate his own exploits there is plentiful documentation for his extraordinary career as an explorer and adventurer in China, as a wartime liaison between the Communist Chinese leaders and the United States and his later liaison role with the Chiang Kai Shek forces after they fled to Taiwan. Equally remarkable was his career as leader of a commando reconnaissance force in Pyongyang during the Korean War. He had a swashbuckling aura that made every encounter with him memorable.

His subordinate officers, who were the intermediate link between Jim Potratz and myself in the Translation Section, also worked in his offices in MACV headquarters were somewhat lower-key. Capt. Charles (Chuck) Cattenach was an even-keeled officer, who did not attempt to fabricate a “command presence” and interacted with his subordinates with casual ease. This adversely affected his career prospects. He remained in the grade of captain for many years and eventually was forced to retire at that grade. Chuck Cattenach eventually ended up in Orange County, running a restaurant with his much younger Thai wife.

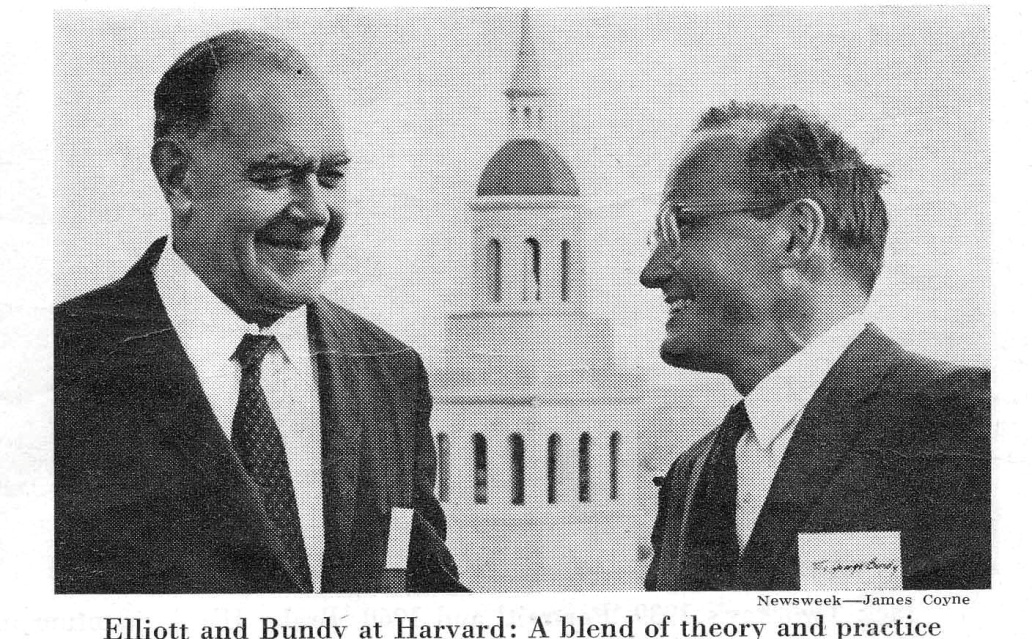

At the bottom of the pecking order, but most essential to the effective functioning of the Collection Branch, was the most un-military officer in the entire MACV headquarters, Second Lt. David Morell. He was a Princeton Ph.d who had received a direct commission to discharge his military obligation. David became a life-long friend. In later life he became a noted expert on Thai politics, with total fluency in the language, and after that a world class environmental analyst. Needless to say he had analytic and writing skills that made him indispensable to the J-2 MACV Collection Branch. He was a quick study who intuitively grasped how to put together a compelling report, and which tabs and appendices should go where to be most persuasive. I doubt that Col. Young expected much spit and polish from David, and was grateful for his skill in keeping the bureaucratic wheels turning.