6

Patrick Devey, Algonquin College

INTRODUCTION

Algonquin College made the strategic decision to declare itself a digital college in 2009 because it recognized that the evolution of educational technology had catalyzed a transformational shift in education. For Algonquin, to be digital meant making a commitment to invest in its technological infrastructure and in its people and resources to provide increased access, flexibility, mobility, and personalization of its products and services to its clients. It meant fostering a learner-driven, “bricks and clicks” environment where students could seamlessly transition between learning modalities and devices at their own pace, from anywhere, and at any time.

As a digital college, Algonquin College adheres to its mission of “transforming hopes and dreams into lifelong success” (Algonquin College, 2017, p.11) by leveraging technology to create a personalized learning environment, addressing the distinct learning needs, interests, and aspirations of its individual students. This case study explores Algonquin College’s digital learning journey to provide more personalized experiences for its learners to acquire the necessary skills and knowledge needed for a successful transition to the workforce.

EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY

A Brief History

It could be argued that the earliest forms of educational technology can be traced to pre-historic times with the earliest forms of human communication, including primitive human speech (sounds) and cave paintings (visual, symbols). The evolution of language allowed humans to use oral communication to listen, memorize, and recite common sounds that could be interpreted and understood. This certainly improved the survival rate of early humans as it allowed for better cooperation, the sharing of information and best practices, and it protected them from danger (University of Minnesota, 2016). As the lexicon became more sophisticated, so did written communication. The development and adoption of an alphabet provided a means to record and transmit knowledge in a more accessible and consistent manner. The invention of the printing press allowed for the mass production of books, poems, and music to be distributed and accessed by more people, and as the transportation industry improved, so did the propagation of the written texts and of people who could help interpret them.

The field of education can vaunt a rich history of technology use in the dissemination of knowledge to learners across the world (Saettler, 1990). The development of instructional media channels, first with the radio, then the television, allowed for content to be broadcast. Audiovisual technologies provided new opportunities to design and produce instructional content—and the ability to capture and record this content on cassettes, laser discs, and other devices—further increased its availability to learners. The audiovisual instruction movement played a seminal role in the rapid and effective training of civilians in the United States to work in industry during World War II (Reiser, 2001).

The adoption of computers offered yet another new channel to design and deliver instruction. Computer-based instruction was used to create more personalized and interactive instructional activities, such as drill-and-practice exercises, tutorials, simulations, and games. The advent of the Internet, the implementation of the World Wide Web, and the rapid pace with which technology has immersed itself into our daily lives has catalyzed a paradigm shift in the field of educational technology. The era a digital learning saw a shift from technology being used to complement traditional teaching methods to one where it is relied on as the core method of delivery (Bates, 2015).

Digital Learning

Digital learning refers to the variety of practices that leverages technology to facilitate learning. What differentiates digital learning from other forms of educational technology is that it allows for increased opportunities for the personalization of the learning experience by shifting the locus of control from the content deliverer to the content consumer. With digital learning, the learner is empowered in their ability to influence the time, place, and pace of their learning experience.

There is much more to digital learning than providing learners with access to a connected device. Rather, digital learning is the result of a combination of technology, content, and instruction (State of Georgia, Governor’s Office of Student Achievement, n.d.).

- Technology: By using a combination of a learning management system, virtual classroom software, and/or rapid eLearning development tools, educators leverage technology to develop and deliver content to be consumed on a variety of devices.

- Content: Educational materials are designed and developed to be transmitted to learners using digital technology. Effective digital learning assets will have adhered to best practices in instructional design and would have been produced using a purposeful mix of media tailored to its intended audience (text, audio, visuals, video).

- Instruction: Educational experts are essential in both the design and in the delivery of digital learning content. Much like in a traditional classroom setting, creating effective learning content requires a subject matter expert who understands how best to design and deliver instructional content in such a manner that it has a high likelihood of being understood by its intended audience. In the context of digital learning, it also requires expertise in repurposing content so that it is optimized in a digital setting, as well as skills in monitoring the progress of learners and providing them with personalized feedback using various digital communication tools.

Digital learning can take on many different forms, from blended or hybrid learning (combination of digital and classroom-based activities, including “flipped” classrooms) all the way to learning experiences that occur entirely online (Siemens et al., 2015). Moreover, education professionals will combine a variety of tools, techniques, and technologies from a larger learning ecosystem to create customized digital learning experiences. For example, an online course on financial investing could include the use of resources such as: selected electronic articles from the library, a free online textbook from an open educational resource database, links to particular social media channels, a discussion platform to share ideas and answer common questions, a virtual classroom for collaborative exercises, a stock market simulation application for a mobile device, and embedded gamification elements such as badges and leaderboards to add an element of competition to encourage learner engagement.

DIGITAL LEARNING AT ALGONQUIN COLLEGE

Although it declared itself a digital college in 2009, Algonquin College’s foray in digital learning extends well before that time. It has a long-standing reputation as a provincial leader in the innovation and integration of digital learning amongst post-secondary educational institutions (Canadian Digital Learning Research Association, 2018, p.60). Through the dedicated efforts of different committees and departments at the College, continual investments have been made in its digital infrastructure, including several educational technology initiatives. Early examples of Algonquin College’s strategic investments and initiatives in digital learning include:

- the co-founding of the OntarioLearn Consortium in 1995. This innovative arrangement has fostered the sharing of online courses amongst all 24 Ontario colleges. Its library has over 1,200 online courses, over online 550 programs, and more than 75,000 student enrolments annually (OntarioLearn, 2019);

- the creation of its first computer access centre in 1996;

- the implementation of wireless network access across the College in 2000;

- the creation of the first e-classroom in 2000;

- The first mandatory student laptop program in 2000 (all students enrolled in a targeted program were provided with a laptop);

- the adoption of a learning management system and launch of its first online courses in 2001;

- the creation of a hybrid (in-class and online) course development plan in 2002;

- the conversion of all General Education courses to asynchronous online courses in 2002; and

- the adoption of simulation software for all Microsoft Office training in 2004.

With the rapid growth of the College, and the challenges that it was causing on space and scheduling, a decision was made to increase the number of hybrid and fully online programs. Up to that point, online programs had been reserved for students studying on a part-time basis, so the move to full-time online programs was a first for Ontario colleges in 2008.

These initiatives helped transform the College’s organizational culture to one that embraced the use of technology, and in doing so, set the blueprint for the decision to proclaim itself a “digital college” in 2009. The articulation of the College’s initial digital strategy followed soon thereafter in 2010.

The digital strategy highlighted the fact that digital learning provided a means to extend Algonquin College’s existing delivery model to allow learners to personalize their experience in their own style and at their own pace. Furthermore, it acknowledged that by better leveraging technology to deliver its products and services, the College could alleviate some of the space and scheduling challenges it was facing and continue to grow enrolment. As an added benefit, the technology would provide additional means to connect its learners and faculty directly to the industry, its communities of practice, and to its vast amount of resources. At the heart of its investments in the digital college initiative are two of the foundational tenets of Algonquin College: (1) access to education for all, and (2) preparing its graduates for success in the workforce.

In the context of digital learning, access could mean providing instructional opportunities to learners in remote areas of the province, to individuals who are unable to come to campus during “regular” class times because of work or family commitments, and those who could not afford to move closer to Algonquin College’s Ottawa, Perth, or Pembroke campuses to attend school. Using digital technologies also meant that students who require accommodations, such as specialized screen reading software or are otherwise unable to follow the pace of traditional lectures, can benefit from added opportunities to tailor the instruction to their needs.

Embracing digital learning in the design and delivery of curriculum also meant that graduates are better prepared for the workforce. Integrating simulations or authentic software in the course design provides learners with low-risk experiential learning opportunities that allow them to hone the practical skills they will need in the workforce. For example, students enrolled in Interactive Media Management benefit from a campus-wide service agreement with Adobe Systems to use their suite of software in their courses, the same tools they will need to use to work in the industry. Furthermore, digital communication tools can be used to connect the learners and faculty with industry experts to help reinforce and apply the theoretical knowledge taught in class with real-life, practical examples from the workplace.

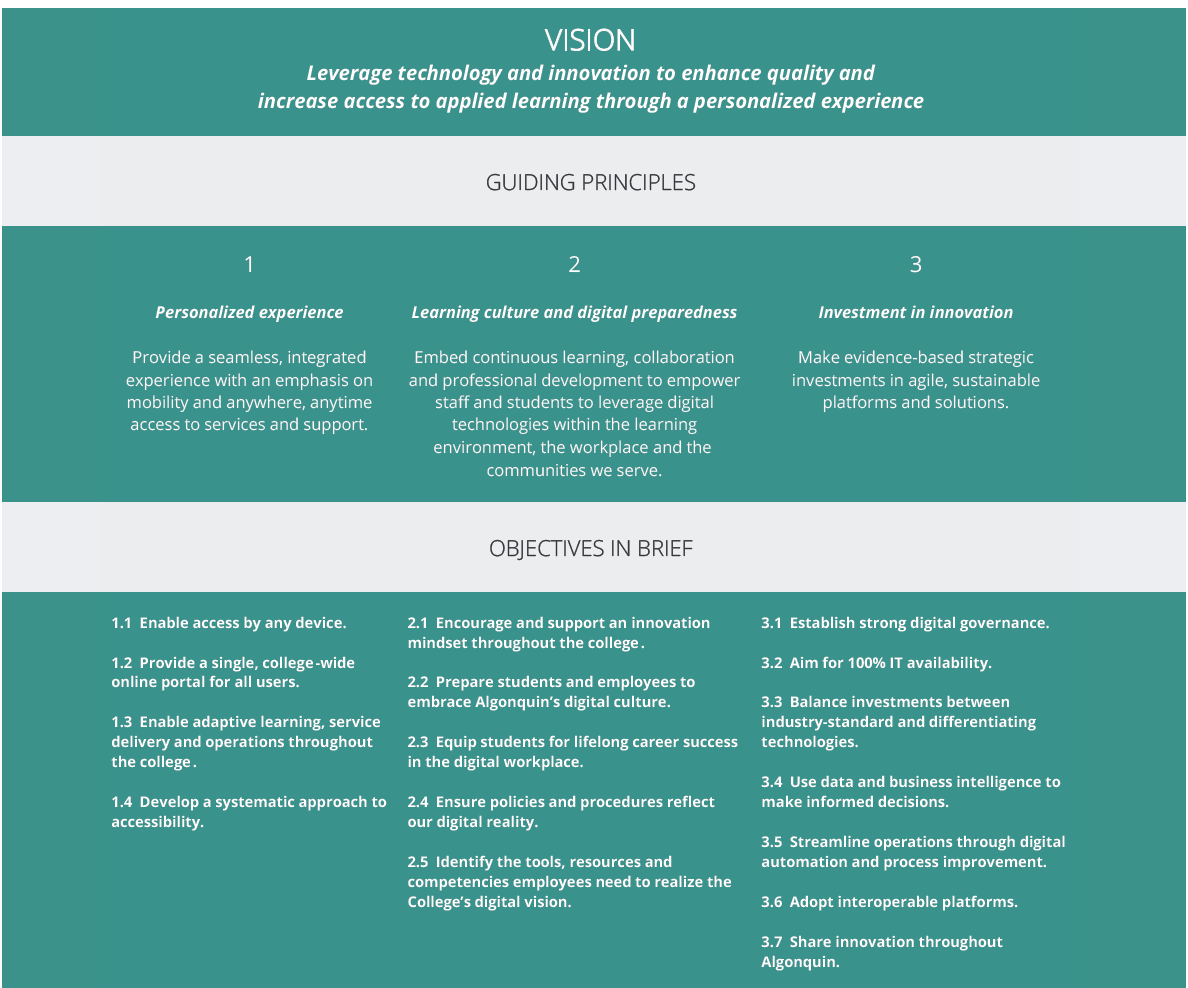

DIGITAL STRATEGY 2.0

Released in 2015, Algonquin College’s renewed digital strategy, entitled The Next-Gen College, was an attempt to consolidate some of the many digital initiatives that had been launched at the College under a set of guiding principles to inform future related activities. The overarching vision of the strategy was to “leverage technology and innovation to enhance quality and increase access to applied learning through a personalized experience” (Algonquin College, 2015, p.5). The three guiding principles identified were grouped under the themes “personalized learning”, “learning culture and digital preparedness”, and “investment in innovation” (figure 1).

Figure 1

The Vision, Guiding Principles, and Objectives of the Digital Strategy 2.0

NOTE. Algonquin’s Digital Strategy 2.0 was published in 2015.

1. Personalized Learning

The personalized experience, which is also a main tenet in Algonquin College’s most recent strategic plan (Algonquin College, 2017), aspires to “provide a seamless, integrated experience with an emphasis on mobility and anywhere, anytime access to services and support” (Algonquin College, 2015). This vision is highlighted by the objective to provide the learner the ability to transition between devices seamlessly.

With a personalized learning experience in mind, this could mean that a student could start an activity with one device and complete it using another. For example, they could start an assignment by reading the instructions on their phone, watch a related video on their television, and answer the associated discussion questions using their tablet or laptop. With that lens, it suggests that students are not only going to pick their preferred device to consume the content but are also more likely to choose a device for a certain kind of activity (e.g., opting to watch the video on their big screen television rather than on the smaller screen of their phone).

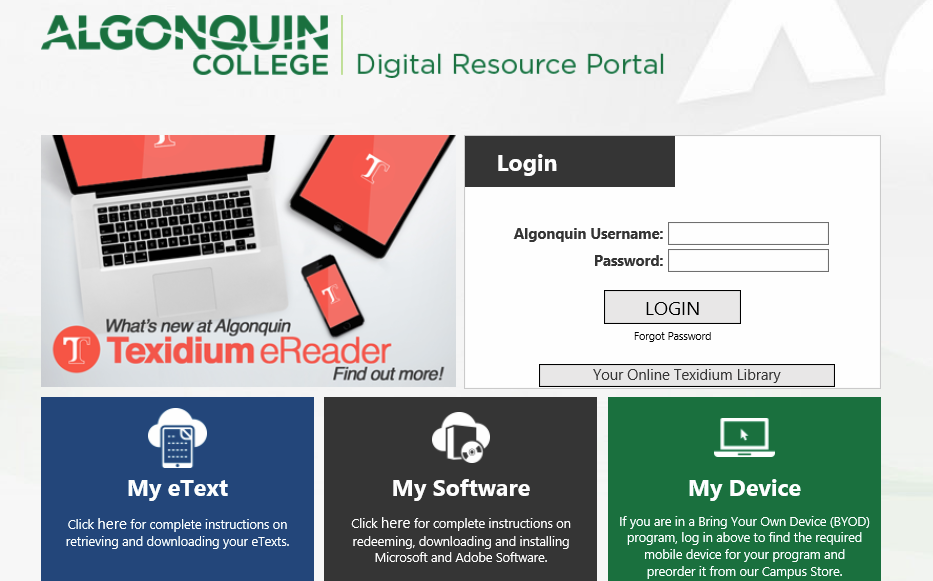

Digital Resource Portal

One of the objectives outlined in the digital strategy to promote personalized learning is the consolidation of the digital services into a single, college-wide online portal. The Digital Resource Portal merges major digital learning initiatives such as eTexts, resources associated to the Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) project, and Online and Educational Resources together into a common interface (Figure 2). In addition to simplifying the access to these resources for students and faculty, it also provides a means to track the activity to determine how they are being used to continually improve the service. Each of these major digital learning initiatives is described in more detail.

Figure 2

Screenshot of Algonquin College’s Digital Resource Portal

NOTE. From Algonquin’s Digital Resource Portal

The Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) Program

An initiative undertaken by the College to promote mobile accessibility is the Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) program. This program, which started in 2000 with one department and now extends to the majority of programs of study at Algonquin, provides all learners with access to industry leading software and online resources. To participate, students are required to possess a mobile computing device that meets or exceeds the minimum recommended hardware requirements identified for that program.

As part of the program, over 200 classrooms were converted into “mobile-ready” learning spaces. This included augmented wireless access hubs, digital projection capabilities, touchscreens for all teaching stations, and convenient access to electric plugs for all students in the classroom.

The purpose of the BYOD program is to provide access to course materials at any time and from anywhere, foster collaboration amongst learners, provide skills with tools that are used in the industry, and most importantly, to produce graduates who are confident in using technology in both a learning and a workplace environment.

Online and Educational Resources

To assist students with acquiring the skills necessary to thrive in a digital learning environment, and later in the workplace, Algonquin College has negotiated college-wide license agreements with select software providers. This collection of software is available for students to download via the portal, and the licensing cost is included as a fee paid as part of the registration process.

For instance, all students can benefit from both the software and support from trained staff to help them record and produce media, annotation software that allows them to take notes and record presentations and tutorials, specialized software that supports voice dictation and screen reading, and tools to create and share online surveys to record and analyze data for research projects.

Students enrolled in BYOD programs can also access digital copies of Microsoft Office (Word, Excel, PowerPoint, etc.), Microsoft Windows (operating system), as well as Adobe’s Creative Cloud software (Photoshop, InDesign, etc.). Furthermore, students needing access to specialized lab-based software could access it using one of over 100 virtual machines as part of the Virtual Desktop program.

The eText Program

One of the more ambitious projects undertaken by Algonquin College as part of its digital strategy is the campus-wide adoption of electronic textbooks (known as eTexts) in 2015. This initiative made use of specialized technology to provide students with instant access to their assigned course textbook in a digital format via their preferred device. In addition to their ability to consult course materials from anywhere at any time, moving to eTexts allowed for significant cost savings for students in the overall cost of their textbooks, in addition to promoting an eco-friendly alternative to print-based texts. Furthermore, it was believed that by providing students with an easy-to-use method to access all their required course materials at the onset of the term would also have a positive effect on student success.

As part of the strategy for eTexts, Algonquin partnered with Kivuto Solutions to develop an end-to-end eText solution and adopt a cloud-based eReader called Texidium. eReader software facilitates the reading of electronic materials, such as textbooks, by providing multi-platform support (e.g., optimizing the display for different screen sizes), as well as providing basic features such as adjusting the font size, zoom capabilities, and word search. The Texidium software provided additional capabilities such as the ability to “bookmark” (to pick up from where you left off), advanced note-taking and annotation capabilities, and multilingual product support for all users. In addition, the Texidium platform consolidated all electronic textbooks purchased by students into a common portal area to simplify access to these resources.

As an added feature of the eText initiative, students and faculty have access to enhanced interactive features created by publishers to accompany a given textbook, or as a stand-alone tool. For instance, materials distributed in the ePub3 format make use of the latest HTML5 standard to embed video, audio, images, and interactive activities. This allowed for a much more engaging experience than the standard “pdf” version of an existing textbook.

The additional materials could include practice quizzes, multimedia resources such as video case studies, mini-lectures, interviews, or interactive simulations. In addition, faculty could use the built-in tools offered by these digital platforms to assign activities to their students, track their progress, and conduct assessments. Faculty also enjoyed the benefits of having instant access to textbooks to evaluate for adoption for their classes rather than ordering, then waiting for textbooks to be mailed to them.

eText Distribution Models

There are three distribution models for eTexts at Algonquin College: Institutional Pay, “Enhanced” Student Purchase, and Student Purchase. With the institutional pay model, all eTexts associated to particular levels in certain programs are automatically included as part of program registration fee (e.g., Level 1 of the Early Childhood Education program, Levels 1-4 of the Construction Engineering Technician program, etc.). With this model, students can permanently save all the digital resources (as a pdf), have complete control on printing (i.e., no page limits), and save over 40% on the cost of the printed textbook. However, with the institutional pay model, participation in the eText initiative is mandatory for all students enrolled in the program, meaning that it is included as part of the tuition fees.

If the textbook is not included as part of the institutional pay model, students do not pay for the resource as part of their program registration fee but can still opt for an eText version of the assigned textbook in one of two ways. If the eText version of the assigned textbook is included in the college’s Virtual Bookstore, students can purchase it and enjoy the same benefits as the institutional pay model regarding downloading a pdf version and printing. This is known as the “Enhanced” Student Purchase model. If the assigned textbook is not available in eText format through the Virtual Store, students who want a digital copy of the textbook can do so by purchasing an access code through the college’s Connections Bookstore, on Amazon or another eBook retailer, or directly through the publisher’s website. In those cases, the electronic resource is not associated to the college’s Digital Resource Portal.

eText Results

The outcomes of this innovative project since its inception in 2013 have been mixed. Results from longitudinal grade analysis showed that there was no significant net effect on the retention nor on the success rates among students who were enrolled in programs that made use of eTexts when compared to those who did not. In addition, there were some initial challenges with the deployment of the custom system, leading to frustrated students and faculty. These issues were eventually resolved, and the system has improved with each academic year.

As the eText program continues to evolve at Algonquin College, the future of Institutional Pay Model (IPM) is still unknown. Students have voiced concerns about the requirement to purchase these resources, suggesting instead that they have the choice to do so (and in their preferred format). There were also some questions about what constitutes “required material” for the courses, and who determines this. Furthermore, the increase in the quality and quantity of open educational resources (OERs), particularly due to the leadership in the field by OER Commons, BCcampus, and more recently eCampusOntario, has provided the college system with no-cost alternatives to traditional publisher resources. Despite the latent faculty adoption rates of these resources, it is showing signs of increasing as they become more aware and increasingly confident in the quality of the OERs being made available (McKenzie, 2017).

Learners also have access to free educational content: bite-sized “do-it-yourself” videos found on YouTube, free Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) (e.g., Coursera, edX, Futurelearn), online tutorials and lectures from Khan Academy or LinkedInLearning (Ontario post-secondary institutions benefit from free access via a government-funded licence agreement), and interactive exercises to learn specific skills such as coding with Code Academy. With so many freely available options to supplement in-class content, the traditional reliance on textbooks in higher education is dwindling – much to the chagrin of the academic publishing industry.

Based on the results of the eText program and feedback received from students who want more choice with the adoption of their course materials, Algonquin College has decided to scale it down to specific academic programs.

Challenges with the Personalized Experience

More can be done to provide a seamless, integrated experience for mobile learners, instructors, and staff at Algonquin. If students and faculty are truly to expect access to their learning content from anywhere and at any time, additional investments will need to be made to augment the services and support provided to them. The traditional support model of face-to-face service during “regular” business hours at the College will no longer be feasible. Classes are increasingly being offered on weeknights and on weekends, users access the system from different time zones, and an increasing number of digital learners and instructors are active late at night and in the early morning. A true personalized experience will require just-in-time service to learners and staff outside of traditional business hours using a variety of communication technology (e.g., phone, desktop conferencing, live chat, etc.).

At no time was this need more prominent than at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Suddenly, with both leaners and staff being forced to study or work remotely, there was an urgent need to rapidly pivot a mostly on-campus delivery model to one that could be offered entirely at a distance. For colleges this meant a significant amount of investment in new technology and training, as well as scaling up systems and tools that they already used.

Will some or all of these services continue to be offered remotely or in a hybrid mode (on-campus or remote) post-pandemic? Only time will tell. It would be a shame to squander all the efforts, resources, learning, and good practices that occurred with the shift to remote service delivery during the pandemic. Colleges that immediately revert to the “old ways” as soon as they can will risk the resentment of certain learners and staff who had grown accustomed to the convenience offered by remote service delivery. On the other hand, colleges who build on this experience will consider augmenting their personalized support services by investing in more tools and technology, and by extending beyond usual operating hours, thereby offering a true “hybrid campus” delivery model.

However, delivering a hybrid campus service model is fraught with challenges. Most obviously, most educational institutions are simply not setup for it. The systems, processes, policies, reports, and services offered in post-secondary institutions are tailored to the “traditional”, fixed, two-term, on-campus, full-time, direct-entry student. Granted, there has been some adaptations to the status quo over the years, as colleges can no longer ignore the rise of hybrid and online programs being offered, as well as the increase in “non-direct” students who do not transition to post-secondary studies immediately after high school (e.g., adult learners).

In a true personalized experience, a student could theoretically complete the requirements for their credential in more time or less time than “prescribed” by the curriculum. Doing so would mean altering the provincial government’s funding and accreditation process since they are typically based on seat time, and not on the demonstration of competency.

In Ontario, colleges are funded much less for students who opt to study on a part-time basis, when compared to those who study full-time. This historical inequality in the funding formula has significantly contributed to the disparity in the opportunities and in the support offered to students who choose to come to school on a part-time basis. At Algonquin College, much like the other colleges in Ontario, part-time students are handled by a specific department (e.g., School of Part-Time Studies, Continuing Education, etc.), as opposed to favouring the integration of all students, regardless of their status, in the same classrooms. The switch to a corridor-based, and then performance-based, funding model will force colleges to rethink their operations and the experience they provide part-time learners.

At Algonquin College, there are a few programs that are offered monthly (as opposed to once or twice a year), and others have continuous start dates where students can begin their studies whenever they are ready to do so. This activity has proven to be quite challenging to:

- Schedule: since the student information and scheduling systems are not designed to handle “irregular” terms;

- Market: since the marketing annual cycle is primarily designed for direct entry students starting in the Fall or the Winter term;

- Staff: in an environment where the summer months are usually reserved for annual vacation and working within the framework of collective agreements; and

- Operationalize: since faculty would no longer control the pace of instruction and must instead be available to provide feedback and guidance at times when the learners need it until they have achieved their objectives.

Although the path to personalized learning is fraught with obstacles, they are not insurmountable. Improving and better leveraging the Prior Learning Assessment Recognition (PLAR) process is one way that students coming to school with prior knowledge and skills can be “fast tracked” in their program of study.

Academic Chairs and faculty have figured out creative ways to disperse the workload in continuous intake programs. Scheduling systems are being adapted and “work arounds” are being identified to accommodate term dates that do not fall in the usual mold. These are some examples of the growing pains that will be involved in creating a more personalized journey for our learners.

Opportunities with the Personalized Experience

Another objective that was identified under this guiding principle was enabling adaptive learning at the College. Adaptive learning makes use of computer algorithms to customize the learning activities and content to the individual based on their interactions with the system (EDUCAUSE, 2017). If the student is demonstrating an understanding of a topic, the system will increase the complexity of the content or move the learner through at a quicker pace to get to the next topic. On the other hand, if the system senses that the learner is struggling, the pace of the lesson can be slowed down, the complexity of the content can be reduced, and remedial content can be pushed to the individual.

In theory, adaptive learning presents educational institutions with an opportunity to deliver personalized learning at scale (EDUCAUSE, 2017). It provides a means to shift from a “one size fits all” approach to curriculum delivery to one that considers the diverse knowledge, skills, and needs of the individual. Designing and implementing an adaptive learning system requires extensive development work on the curriculum and on the content and assessments associated with the individual learning objectives.

Certain academic publishers have developed practical examples of adaptive learning systems as they look to repurpose and evolve their vast libraries of content differently. With advances in the capabilities of learning management systems, particularly with learning analytics, a growing number of educational institutions—including Algonquin College—are exploring this technique to assist faculty with designing personalized pathways for learners, as well as to further support student success initiatives.

2. Learning Culture and Digital Preparedness

The second principle, learning culture and digital preparedness, seeks to foster a culture of innovation throughout the college, one that supports agile methods and informed risk-taking to “empower staff and students to leverage digital technologies” (Algonquin College, 2015, p.5). This mindset is one that is also reflected in the Algonquin College’s strategic plan (Algonquin College, 2017), as well as in its focus on lean management practices. Concerning the digital strategy, this principle seeks to encourage continuing learning, professional development, and collaboration by employees using technology to improve processes and their own efficiency. This means exploring new tools and systems; mining and interpreting data to make informed decisions; and encourage continuous learning and improvement of employees through training, professional development, and collaboration.

The creation of a digital learning culture at the college not only supports faculty and staff initiatives to enhance their digital workplace skills, but it also sets the blueprint for students to acquire similar skills that they can transfer to the workplace. In this way, the digital strategy helps shape graduates into employees that can “thrive, adapt, and continually develop in the constantly evolving digital workplace” (Algonquin College, 2015, p.14).

The Employee Learning Exchange

One of the initiatives undertaken at Algonquin College to help catalyze a learning culture and digital preparedness is the creation of the Employee Learning Exchange (ELX). The ELX represents an area at the College where computer technicians, trainers, educational technologists, instructional designers, and multimedia specialists are grouped in a common working environment to assist employees with digital skills training, digital asset development, and with the innovative use of educational technology tools. What differentiates this space from other areas of the College is that it is dedicated to employees (faculty and staff) and their work, and it brings together expertise from different areas of the College; Instructional Technology Services (ITS); the Centre for Organizational Learning (COL); Learning and Teaching Services (LTS); and AC Online, Algonquin’s online campus (ACO). Inspired by Apple’s Genius Bar concept, the idea is that employees seeking to use technology to improve a workflow, or who want to try a new initiative, can be matched with an individual with the technical and/or pedagogical expertise required to help them achieve their goals.

Academic Policies and Procedures for Digital Learning

One of the objectives supporting the learning culture and digital preparedness of Algonquin’s students and employees is to ensure that policies and procedures reinforce the College’s commitment to digital learning. In 2001, an academic policy was established that set the expectations for the use of the College’s Learning Management System (LMS) by faculty. The purpose of this policy is to ensure that students have access to essential course materials, resources, and other relevant information about each of their courses within the LMS (Algonquin College, 2019). This existence of this policy also recognised the LMS as a critical component of Algonquin’s digital strategy, as well as provide students with expectations for the consistent use of this system throughout their studies.

Another example Another example of an academic process at Algonquin that supports digital learning is the requirement of a minimum threshold of digital learning in each new program proposal. For each new program that is brought forward for appraisal, there is an expectation that regardless of the topic, at least 20% of the program must be delivered using technology. This could include a few hybrid courses, as well as the inclusion of a fully online course, such as those offered as general education requirements for certain credentials.

In both these cases, faculty are challenged with rethinking how they design their curriculum and prepare their course materials to be delivered using technology. In doing so, learners can benefit from access to their course materials round-the-clock, and they are no longer restricted to the physical classroom to continue their learning experience. By reinforcing the need to use technologies as part of the learning process, learners become more adept at using the tools to become more independent and responsible for their continuous learning at school and in the workplace.

Challenges with Learning Culture and Digital Preparedness

One of the challenges faced by Algonquin with the LMS policy is the difficulty in making sure that it is adhered to. Despite best intentions in providing realistic expectations to students about consistency in their digital learning experience, there is still much work to do in this area.

In a survey conducted in April 2017 as part of the LMS renewal project, students voiced their discontent with the use of the LMS in their courses. One of the most frequent comments heard from the students was the inconsistent use of the LMS, such as certain features being used in some—but not all—courses, or the menu items and navigation being different from course to course, even within the same program. Tracking the use of tools in the system was further complicated by the fact that over the last few years, different departments were using different versions of the LMS software, or in one case, a different LMS altogether.

Where there was some success in this area was in having new faculty make use of a common template to ensure consistency with naming and navigation. But retrofitting existing courses into a new shell continues to be a challenge, as faculty prefer to copy and reuse their existing courses with every new term. There have also been challenges in retraining faculty due to other professional development commitments, limited opportunities to conduct the training, and limited training resources.

After an extensive and iterative process, Algonquin College selected a new LMS to be used across all campuses starting in the fall of 2018. The implementation of the new system, Brightspace by D2L, involved mandatory training sessions for all faculty, an update to the LMS policy, and the use of metrics to measure student and faculty satisfaction as part of the college business plan.

Opportunities for Learning Culture and Digital Preparedness

The opportunities to rectify the challenges are timely; Algonquin College is consolidating all the existing courses onto a new LMS, the outcome of a procurement process that spanned over a year. The implementation of the new digital learning environment will require the migration of course content from the other systems to the new one. It will also require the recreation of standard course shells with common naming and navigation; the revision of the governance of the LMS; extensive training for all students, faculty, and staff; and a renewed commitment from the College to invest in resources to support students and faculty with their individual needs as they learn the new system.

The renewal of the LMS has also presented an opportunity to revisit the policy associated with it to ensure that faculty training is aligned accordingly and that reporting mechanisms are built into the system to allow for the adoption and usage to be appropriately tracked. The migration to a common LMS was Algonquin College’s chance to reembrace digital learning with improved procedures and processes, investments in student and faculty training and support, and just as important, display a renewed commitment as a digital college to its stakeholders and to the community.

3. Investment in Innovation

The third principle of Algonquin’s digital strategy involves its role in making “evidence-based strategic investments in agile, sustainable platforms and solutions” (Algonquin College, 2015, p.5). The objectives under this principle of the digital strategy focuses on the establishment of digital governance, the use of analytics to make informed business decisions, ensuring a reliable and up-to-date technical infrastructure, using technology to improve processes via automation, and sharing business intelligence and best practices throughout the college for the consumption and benefit of all.

COMMS: Course Outline Mapping and Management System

The Course Outline Mapping and Management System (COMMS) enables faculty and staff to create, approve, and store course outlines in a central, web-based repository. Furthermore, it permits its users to map the course curriculum to program outcomes, as well as create curriculum maps.

This system, which was designed and developed by Algonquin, provided much needed logistical support to the academic sector, which had been struggling to manage the ever-growing list of changes and approvals associated to its course outlines. In addition, the system helped to quickly pinpoint curriculum that would need to be altered as a result of the annual curriculum review process, as well as identify potential duplication of curriculum between programs. Lastly, it provided a means to catalogue, organize, and search through the vast list of vocational learning outcomes, essential employability skills, course learning requirements, and program learning outcomes associated to the College’s numerous programs—past and present. This system has since been shared with several other Ontario colleges.

Learning Management System

The Learning Management System (LMS) is likely the only system that both students and faculty access daily. In a digital college, it is a critical platform. The LMS provides the College with the means to deliver digital content associated with courses and programs of study, fosters a community of learners through its communication tools, provides a platform to create and deploy assessments, and it allows faculty to assess the progress of students to better serve their learning needs. As part of its digital learning strategy, all courses, whether they be offered in-class, as a hybrid, or entirely online, have a dedicated space in the LMS that faculty must use to store course materials, as decreed by the academic policy governing the learning management system.

Although most LMS come pre-packaged with applications meant to enhance the learning environment (e.g., tools to create assessments, record video, host virtual classrooms, etc.), Algonquin’s LMS strategy is to use it as the centrepiece of a larger digital learning ecosystem. Several other applications that users can test, appraise, and adopt complement the tools that come with the LMS. For example, the LMS leverages application programming interface protocols (APIs) to allow learners to connect to other tools, such as those created by publishers, apps that help detect plagiarism, or to resources found at the library, email, or to other College systems.

The LMS represents a key investment by the College, not just to fulfill the digital plan, but to act on it. Each guiding principle identified in the digital plan requires the use of the LMS in fulfilling some of its underlying objectives. The digital plan’s emphasis on a personalized experience through mobility and the ability to access their learning from anywhere and at any time requires a learning management system to store and provide access to the content. The system’s ability to track learner progress provides faculty and support staff the opportunity to provide customized feedback to the learner. By making use of its built-in features, course designers can create customized experiences that leverage conditional content release and branching scenarios.

By investing in resources to help train and support faculty and students in the use of digital technologies, and by reinforcing the ubiquitous adoption of the LMS with targeted policies and processes, the College promotes the learning culture needed to bestow the digital skills and knowledge required to succeed at school, and in the workplace.

Digital Governance by Committee

Digital governance is addressed via different committees at the College. The College Technology Committee (CTC) is an inter-departmental group comprised of delegates from all the major areas of the college, including a representative from the student association. Sponsored by the Vice President, Innovation and Strategy, the mandate of the CTC is to serve as an advisory and advocacy group for the technology-using clients of the College, as well as to recommend strategies and initiatives to act on the digital strategy. The CTC also established two sub-committees, one that focuses on the adoption and use of educational technologies by faculty and students, and the other that provides guidance on tools used by employees across the College as part of their daily work.

Another example of digital governance at Algonquin is the recent establishment of the Learning Management System Steering Committee (LMSSC). It is a group comprised of students, staff, faculty, and managers – the College’s LMS stewards. The group also played a seminal role in the procurement and implementation of the new digital learning environment at Algonquin College. Reporting to the LMSSC is a working group of faculty, students, and staff who provide feedback and recommendations on software updates, technical issues, and opportunities to improve the user experience with the LMS.

Business Intelligence

The ability to make data-informed decisions required that the College invest in resources that could provide this data to them. As part of this strategy, the College created Business Intelligence Services (BIS), a dedicated team to support Algonquin’s business analytics and reporting requirements. As part of its services, BIS provides managers with customized reports through the consolidation of data found on several of the College’s existing systems (e.g., Financial, Human Resources, Student Information System, etc.). They also help gather the necessary data to help the College produce its mandatory reports to the government, including those for the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and for the Strategic Mandate Agreement (SMA).

To produce these reports, and to create the customized dashboards for the decision makers, the College invested in specialized tools (IBM’s Cognos, Microsoft’s Power BI), as well as the support needed to train the staff. The College’s ability to make informed, data-driven decisions requires not only that the consumers of this data have access to it when they need it (i.e., dashboards, regular reports), but they must also be able to properly interpret and act on the data that they are provided.

The effective use of these tools and reports will allow Algonquin decision makers to better monitor and adjust its new initiatives or improved processes in an agile and sustainable manner. This is also a necessary resource for the successful implementation of lean management practices at the College.

Lean Management

Another objective of the digital strategy is to “streamline operations through digital automation and process improvement” (Algonquin College, 2015, p.14). Continuous improvement also happens to be a major tenet of the College’s strategic plan (Algonquin College, 2017). Algonquin College’s decision to adopt lean management practices aims to empower employees to identify and act on opportunities to continually improve processes and streamline operations. Lean methods rely heavily on the use of analytics to help inform the decision-making process. By leveraging technology to help capture and report this data on a regular basis, employees can determine if their planned actions are having the desired effect and adjust the initiatives accordingly. Furthermore, the successful innovative strategies are shared with the college community to reduce unnecessary or inefficient tasks.

Challenges with Investment in Innovation

One of the biggest challenges facing Algonquin regarding its objective of “streamlining operations through digital automation and process improvement” (Algonquin College, 2015, p.14) is with its need to prioritize which initiatives to endorse. There has never been a shortage of great ideas to improve on the status quo, or a volition to try something new. What is impeding progress on many of these worthy initiatives is a long queue of projects when resources are limited, and the required expertise is not available. Identifying which of the ideas goes to the top of the list and what must wait continues to be a challenge.

Furthermore, lean management advocates will argue that certain activities that are not seen to contribute to the strategic goals of the institution should be stopped so that resources can be reallocated to more “important” activities. Although it may seem simple enough in theory, identifying and agreeing on which activities are important and which are not, is far from a simple task when dealing with many competing priorities in such a large institution.

Opportunities with Investment in Innovation

With an “aim for 100% IT availability” (Algonquin College, 2015, p.5) as one of the objectives for this guiding principle, it was decided that the new LMS would be a cloud-based solution. Up to that point, the main LMS used by on-campus students had been housed and maintained on Algonquin premises for over 15 years. With the number of unplanned outages rising, it became clear that the amount of traffic on the system had grown to the point where it could no longer be maintained on site without significant investments in infrastructure and human resources. Given the shift to more affordable, subscription-based, cloud-based solutions for several IT systems over the past decade (e.g., Algonquin uses cloud-based email services), this provided added reasoning for the decision to invest in a system that can be maintained in the cloud by a third-party with a proven track record for providing this type of service to similar clients.

The challenge in this circumstance was in choosing the right system. Given the importance of the decision, and the amount of stakeholders affected, it was decided to establish a steering committee whose mandate would be to (1) improve confidence in the current system which would still be relied on until fall of 2018, and (2) go through the procurement process to recommend the next LMS to the College’s executive committee. The Learning Management System Steering Committee (LMSSC) was able to rely on an experienced procurement team at the College, on a bevy of research and documentation suggesting best practices and procedures, as well as on the experience of its fellow institutions, many of which had undergone a similar process in the past few years. The LMSSC was successful in competing the selection process on schedule, and the new LMS was implemented in time for the start of the 2018 fall session.

ONLINE LEARNING AT ALGONQUIN

Online learning is a seminal activity undertaken by Algonquin College that is directly linked to its vision “to be a global leader in personalized, digitally connected, experiential learning”, and acts on all three guiding principles of its digital strategy (Algonquin College, 2017, p.11).

Algonquin College is considered a pioneer amongst Ontario post-secondary institutions in distance education. It has come a long way since its first foray in self-directed, correspondence courses in the late 1960s, to co-founding OntarioLearn in 1995, to today’s catalogue of over 900 courses and 90 full-time and part-time programs offered entirely online. In 2018-19, there were over 40,000 course-level enrolments, including more than 3,800 students who opted to study full-time online. In a national survey conducted by the Canadian Digital Learning Research Association, it was found that Algonquin had the most online course enrolments amongst all colleges and institutes in Canada (Canadian Digital Learning Research Association, 2018). As a testament to the ability of the modality to increase access to students, over half of the enrolments in the online programs came from students who lived over 100 km away from the Ottawa campus.

With year-over-year program and enrolment growth at Algonquin, the rapid adoption of online learning as an accessible, flexible, and affordable alternative to the on-campus experience is showing no signs of slowing down. In a report on the state of online learning and distance education in Canada, it was found that enrolments in online learning have increased at a rate of at least 10% per year since 2011 and that 1 in 5 higher education students are enrolled in at least one online course (Canadian Digital Learning Research Association, 2018).

With a need to focus on increasing quality online programing and supporting an ever-increasing amount of online students, the strategic decision was made to create and launch a stand-alone online campus in March 2020. When explaining the reasoning behind a virtual campus, Algonquin College president Claude Brulé described that “…from the moment a learner contacts us about online education, to the moment they graduate, they will receive the same support as someone who studies at any of our other campuses” (Algonquin College, 2020).

The evolution of online learning at Algonquin has not been without its share of challenges, many of which continue to this day. Foremost is the challenge of offering services to students who could very likely never set foot on campus (although the pandemic has alleviated this challenge when many on-campus services pivoted to remote delivery). Another challenge is providing work-integrated learning experiences for students who could be located anywhere in the world. Other challenges include leveraging evolving technology to create an engaging online experience that goes beyond a static website, optimizing the business model to be scalable, and maintaining alignment with on-campus programming.

Services to Online Students

Offering services to students who opt to study entirely online presents some unique challenges since they can be located anywhere in the world while completing the learning activities. The physical distance from the campus can make it difficult for a student to obtain required course materials (e.g., ordering and shipping a textbook), make use of on-campus student services (e.g., counselling, technical support), or even communicate with employees since they might not be available at the time they are needed given the time difference.

A shift towards digital resources, including eTexts and open educational resources, allowed students to have instant access to all of their required course materials the moment they gained access to the course website. Although technologies such as Brightspace (by D2L), Microsoft Teams, and Zoom are commonly used to provide real-time communication between the faculty and the learners during office hours and/or tutorials, the online courses are designed to be delivered asynchronously, meaning that students can access their course materials at any time, from anywhere. Apart from the assessment due dates, learners have control of their learning experience by deciding when they want to engage in the learning activities, and how much time they would like to devote to it.

In 2017-18, the Centre for Continuing and Online Learning (CCOL) managed over 3,000 off-site final assessments, all written in a supervised environment (e.g., proctored at another college or university), including 88 outside of Canada in countries such as Australia, England, Kenya, Pakistan, and the United Arab Emirates. In situations where a student is unable to find a proctor or a suitable location to write the exam, Algonquin has been piloting remote proctoring as an alternate option. With remote proctoring, the invigilator uses the technology embedded in the user’s device (e.g., laptop camera) to monitor the learner as they complete the assessment. The session is recorded and made available for viewing by the instructor and/or manager if needed. Although the use of these services has been drastically reduced at Algonquin College because of concerns over security and student privacy, they continue to be used in a few programs that required a proctored solution for their certification exams.

With a steady increase in enrolments in online courses and programs at Algonquin, catalyzed by the launch of full-time online programs in 2007, the College is increasingly challenged to provide non-academic support to students who are off campus, possibly located in different time zones.

This means that the college has had to consider offering extended hours of operation for some of its service departments (e.g., information technology, library services, registrar), or in the case of AC Online, outsourcing some of its technical support to a service that provides front-line assistance to students and staff twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week.

These are exceptions to the rule, as most of the services are only offered during “regular” business hours, and for the most part, in-person. If Algonquin is to truly provide the full gamut of its services to students enrolled in non-traditional delivery options, it will not only have to consider extended service hours for all front-line support services, but also leverage digital technologies to expand its access beyond the city limits. This could include using web conferencing tools to connect students to academic advisors, career counsellors, nurses, and financial aid counsellors.

Work-Integrated Learning

Work integrated learning opportunities, including placements and internships, can be challenging in online programs. The widespread dispersion of the individual students means that the College cannot rely solely on its already-established network of daycares, schools, clinics, and hospitals in the Ottawa-area for placement opportunities, since for many, getting to these locations would be unfeasible, if not impossible. Therefore, the onus is oftentimes put on the learner to help identify and initiate their own work integrated learning, albeit in conjunction with a placement supervisor who follows up on the lead and manages the relationship with the placement agency. That way, students enrolling in a program that requires a placement will most likely end up completing this within their geographical area.

However, not all work integrated learning needs to be carried out in-person. Instructional designers, working closely with a team comprised of eLearning professionals such as a multimedia specialist, can increasingly leverage technology to create simulated experiences or other immersive activities that allow the learner to practice their newly acquired skills in a low-risk environment.

Designing and Developing Online Courses

Algonquin College benefited from several years of rapid growth in its online enrolments, largely catalyzed by the strategic decision to develop full-time programs online. To accommodate the aggressive course production schedule with limited production resources, the Centre for Continuing and Online Learning (now AC Online) adopted a train-the-trainer strategy. This strategy involved turning the subject matter expert into an online course developer by having them complete structured templates guided by instructional designers. The result was oftentimes a learning experience that relied heavily on a textbook and on an engaging and active instructor who monitored the discussion board and provided timely feedback to the learners.

As the technology evolved, so did the field of online course development. The students who were enrolling in online courses had developed higher expectations based on their experiences with social media, streaming media services, and smart phones. This meant that to meet—and hopefully surpass—the expectations of online learners, a new digital learning production strategy would be required.

To enhance the quality of its online learning products and services, the Centre for Continuing and Online Learning (now AC Online) made the decision to focus their eLearning production efforts to create engaging online experiences. The eLearning strategy hinged on three principal tenets:

- Invest in a core eLearning production team.

- Develop the capacity and expertise of the team members through training, professional development opportunities, and by providing dedicated time to experiment with different software and/or conduct research; and

- less reliance on contractors unless there is a rapid need to scale up production.

- Leverage the subject matter expert (SME) as a team member working with the production team, as opposed to a course developer.

- Acknowledge that in most cases, the SME is not an eLearning expert; and

- Empower the instructional designer to work with the SME, not for the SME, by guiding the course design process and leading the project team.

- Reengineer the production process to promote innovation in the design, quality in the product, and satisfaction of the learners.

- Embed quality checks throughout the process, not just at the end of it;

- Challenge the project team to try something new in the design and development of the course, with less reliance on templates;

- Involve learners in the process through usability test, prototype testing, and focus groups; and

- Place a higher importance on soliciting learner feedback at various times.

What’s Next in Online Learning?

Personalized Learning

Algonquin College recognizes that its immediate prospects for offering personalized learning experiences at scale lie with the use of technology, particularly through online courses and programs. With students already able to access a multitude of programs from anywhere and at any time, the next step that is being investigated is to offer multiple opportunities to start the program, as opposed to waiting for September or January, as is usually the case for on-campus programs. AC Online already offers monthly start dates for certain business programs.

However, a true personalized learning experience would allow the student to set their own pace in the course. This can be achieved by leveraging adaptive learning tools to create distinct learning paths for students based on their interactions with the content, or by designing skills or competency-based curricula where learners can “test out” at their leisure. Both techniques can be used to accelerate (or decelerate) the student’s achievement of the learning outcomes. As mentioned previously, there are several operational challenges that would need to be addressed if the College continues to explore a non-fixed term length.

Micro-credentials and Digital Badging

For a potential non-direct client, one of the main challenges they face in pursuing their education is the lack of flexibility with the scheduling. They are more likely to be older than the traditional full-time student, they have work and/or family commitments, they may already have earned a postsecondary credential, and they are more likely to be seeking the acquisition of specific skills to enhance their employability and/or to advance in their career. These learners have nor the time, nor the need, nor the intention of committing to a 14-week course, let alone enlist in a full-time program of study.

To address the needs of these potential clients, the academic sector is exploring the possibility of creating a set of shorter, more focused experiences to provide learners an opportunity to acquire a skill or demonstrate a performance outcome. This achievement could potentially be recognised by awarding a customized digital badge, or perhaps some sort of smaller course credit. Although the idea of micro-credentialing may represent a more recent trend in mainstream academia, this is not the case in areas like continuing education and corporate training, where short, focused non-credit courses are often the norm.

If Algonquin College is going to invest in microcredentials, it will first need to define what is meant by it and identify how it fits (if at all) in its credentialing framework. Doing so would allow the College to diversify its products and services by providing additional flexible options to its clients as both a provider and as a validator of knowledge and skills for learners and employers alike. With the ability to offer flexible, accessible learning opportunities, online learning will serve as the initial delivery platform to pilot such credentials.

Advanced Learning Analytics

The move to a new Learning Management System has provided the College with an opportunity to revise its organizational architecture in the system, the roles and permissions of its users, as well as the data that is already being collected by other systems (e.g., Student Information System). This is all being done to set the framework to better leverage the built-in analytical tools to help identify students who might be struggling in their program, either because they are disengaged (e.g., not logging in regularly) or because their initial performance on assessments has been poor, so that interventions can be triggered as quickly as possible.

Although these types of tools may have existed with the previous LMS, they were scantly used because of a combination of lack of awareness, lack of training, and most likely because of the difficulty in consolidating the data into useful and timely reports for the employee who needed the information. The implementation of the new LMS has provided an opportunity to reacquaint faculty with these useful tools and help create the regular reporting required to monitor the learning activities at various levels.

Understanding how to use and interpret the data collected by the analytical tools of the new LMS will not only help promote student success, but will also set the framework for future use of the system in creating new personalized learning experiences at the College.

CONCLUSION

For Algonquin College, the digital strategy focuses on the creation of a personalized learner experience, the creation of a learning culture that fosters continuous learning with technology, and a commitment to investments in innovation. These guiding principles continue to fuel the College’s initiatives to evolve its digital learning ecosystem.

As explained by John Bersin (2017), digital learning is not a “type of learning, ”but rather a “way of learning.” For Algonquin College, being a digital college is not just about providing digital learning experiences for the learners, it’s about bringing the learning opportunities to where the students want them to occur.

The selection and implementation of a new LMS has presented Algonquin with an opportunity to reaffirm its commitment to digital learning by better leveraging the built-in tools to offer a seamless, mobile, personalized learning experience for its learners—wherever they might be. The key to its successful implementation and evolution at the College will hinge on the ability to establish a learning culture in which students and faculty feel empowered to leverage the technology to achieve their goals.

The eText project continues to be an industry-leading initiative that provides learners with immediate and convenient access to their required course materials. However, this project also highlighted the importance of partnership with the “clients”—in this case, the learners. If these crucial stakeholders do not consider the initiative valuable, then the College must take appropriate action and revise it. As academic publishers seek to re-invent their industry with new products and alternative business models, Algonquin is poised to leverage its strategic partnerships and leadership in this domain to develop new and innovative solutions to continue to meet the evolving needs of its learners…and the learners made it clear that this solution is no longer via mandatory eTexts.

As the popularity of online learning continues to thrive, particularly amongst more experienced students looking to acquire new skills and knowledge to enhance their employment status, Algonquin will continue to invest in the production and operation of inventive and quality eLearning experiences to meet their diverse needs. The call for more “just-in-time” or accelerated opportunities to earn an academic credential will require the modification of current operational practices to accommodate more flexible and personalized delivery models.

If Algonquin is to realize its vision of being a global leader in personalized, digitally connected, experiential learning, it will need to be able to customize its products and services to the needs of its stakeholders, adopt and optimize the use of evolving digital tools, and understand the needs of industry in a rapidly changing knowledge-based economy.

Although the College’s digital strategy sets the blueprint to guide the objectives to achieve this vision, it must also be agile to respond to the rapid pace of technological change, and to take advantage of the opportunities that they present. This mindset will not only permit Algonquin to lead the post-secondary industry in digital learning, but it will also provide its graduates with the tools they need to transform hopes and dreams into lifelong success.

References

Algonquin College of Applied Arts and Technology (2015, June). The next-gen college: Digital strategy 2.0. https://www.algonquincollege.com/lts/files/2015/10/Digital_Strategy_2.0.pdf

Algonquin College of Applied Arts and Technology (2017). 50 + 5: Algonquin College strategic plan, 2017-2022. http://www.algonquincollege.com/strategicplan/files/2017/01/AlgonquinStrat2017-Pages.pdf

Algonquin College of Applied Arts and Technology (2019, April 17). AA42: Learning management system. https://www.algonquincollege.com/policies/files/2019/06/AA42.pdf

Algonquin College of Applied Arts and Technology (2020, March 6). Algonquin College launches AC online campus. https://www.algonquincollege.com/news/2020/03/06/algonquin-college-launches-ac-online-campus/

Bates, A. W. (2015). Teaching in the digital age. Tony Bates Associates, Ltd. https://opentextbc.ca/teachinginadigitalage/

Bersin, J. (2017, March 27). The disruption of digital learning: Ten things we have learned. http://joshbersin.com/2017/03/the-disruption-of-digital-learning-ten-things-we-have-learned/

Canadian Digital Learning Research Association (2018). Tracking online and distance education in Canadian universities and colleges: 2018. http://www.cdlra-acrfl.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/2018_national_en.pdf

Canadian Digital Learning Research Association (2018). Tracking online and distance education in Canadian universities and colleges: Canadian national survey of online and distance education technical report. http://www.cdlra-acrfl.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/2018_national_technical_en.pdf

EDUCAUSE (2017). 7 things you should know about adaptive learning. https://library.educause.edu/resources/2017/1/7-things-you-should-know-about-adaptive-learning

McKenzie, L. (2017, December 19). OER adoptions on the rise. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/12/19/more-faculty-members-are-using-oer-survey-finds

OntarioLearn (2018). About OntarioLearn. https://www.ontariolearn.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/OL-AnnualReport-2017-2018.pdf

Reiser, R. A. (2001). A history of instructional design and technology: Part I. Educational Technology Research and Development, 49(1), 53-64.

Saettler, P. (1990). The evolution of American educational technology. Information Age Publishing.

Siemens, G., Gašević, D., & Dawson, S. (2015). Preparing for the digital university: A review of the history and current state of distance, blended, and online learning. http://linkresearchlab.org/PreparingDigitalUniversity.pdf

State of Georgia, The Governor’s Office of Student Achievement (n.d.). What is digital learning? https://gosa.georgia.gov/what-digital-learning#_ftn1

University of Minnesota (2016, September 29). Communication in the real world: An introduction to communication studies. University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. https://doi.org/10.24926/8668.0401