2

Essential Questions:

- What are identifiable elements of culture in an organization?

- What are different types of organizational cultures that an employee might encounter?

- How is organizational culture created?

- How is organizational culture maintained?

What Is Organizational Culture?

Organizational culture refers to a system of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs that show people what is appropriate and inappropriate behavior (Chatman & Eunyoung, 2003; Kerr & Slocum, 2005). These values have a strong influence on employee behavior as well as organizational performance. In fact, the term organizational culture was made popular in the 1980s when Peters and Waterman’s best-selling book In Search of Excellence made the argument that company success could be attributed to an organizational culture that was decisive, customer-oriented, empowering, and people-oriented. Since then, organizational culture has become the subject of numerous research studies, books, and articles. Organizational culture is still a relatively new concept. In contrast to a topic such as leadership, which has a history spanning several centuries, organizational culture is a young but fast-growing area within management.

Culture is largely invisible to individuals just as the sea is invisible to the fish swimming in it. Even though it affects all employee behaviors, thinking, and behavioral patterns, individuals tend to become more aware of their organization’s culture when they have the opportunity to compare it to other organizations. It is related to the second of the three facets that compose the function of organizing. The organizing function involves creating and implementing organizational design decisions. The culture of the organization is closely linked to organizational design. For instance, a culture that empowers employees to make decisions could prove extremely resistant to a centralized organizational design, hampering the manager’s ability to enact such a design. However, a culture that supports the organizational structure (and vice versa) can be very powerful.

Why Does Organizational Culture Matter?

An organization’s culture may be one of its strongest assets or its biggest liability. In fact, it has been argued that organizations that have a rare and hard-to-imitate culture enjoy a competitive advantage (Barney, 1986). In a survey conducted by the management consulting firm Bain & Company in 2007, worldwide business leaders identified corporate culture to be as important as corporate strategy for business success.1 This comes as no surprise to leaders of successful businesses, who are quick to attribute their company’s success to their organization’s culture.

Culture, or shared values within the organization, may be related to increased performance. Researchers found a relationship between organizational cultures and company performance, with respect to success indicators such as revenues, sales volume, market share, and stock prices (Kotter & Heskett, 1992; Marcoulides & heck, 1993). At the same time, it is important to have a culture that fits with the demands of the company’s environment. To the extent that shared values are proper for the company in question, company performance may benefit from culture (Arogyaswamy & Byles, 1987). For example, if a company is in the high-tech industry, having a culture that encourages innovativeness and adaptability will support its performance. However, if a company in the same industry has a culture characterized by stability, a high respect for tradition, and a strong preference for upholding rules and procedures, the company may suffer because of its culture. In other words, just as having the “right” culture may be a competitive advantage for an organization, having the “wrong” culture may lead to performance difficulties, may be responsible for organizational failure, and may act as a barrier preventing the company from changing and taking risks.

In addition to having implications for organizational performance, organizational culture is an effective control mechanism dictating employee behavior. Culture is a more powerful way of controlling and managing employee behaviors than organizational rules and regulations. For example, when a company is trying to improve the quality of its customer service, rules may not be helpful, particularly when the problems customers present are unique. Instead, creating a culture of customer service may achieve better results by encouraging employees to think like customers, knowing that the company priorities in this case are clear: Keeping the customer happy is preferable to other concerns, such as saving the cost of a refund. Therefore, the ability to understand and influence organizational culture is an important item for managers to have in their tool kit when they are carrying out their controlling P-O-L-C function as well as their organizing function.

Levels of Organizational Culture

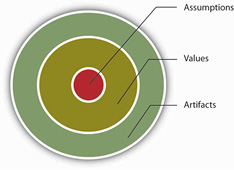

Three Levels of Organizational Culture

Adapted from Schein, E. H. (1992). Organizational Culture and Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Organizational culture consists of some aspects that are relatively more visible, as well as aspects that may lie below one’s conscious awareness. Organizational culture can be thought of as consisting of three interrelated levels (Schein, 1992).

At the deepest level, below our awareness, lie basic assumptions (Figure 1). These assumptions are taken for granted and reflect beliefs about human nature and reality. At the second level, values exist. Values are shared principles, standards, and goals. Finally, at the surface, we have artifacts, or visible, tangible aspects of organizational culture. For example, in an organization, a basic assumption employees and managers share might be that happy employees benefit their organizations. This might be translated into values such as egalitarianism, high-quality relationships, and having fun. The artifacts reflecting such values might be an executive “open door” policy, an office layout that includes open spaces and gathering areas equipped with pool tables, and frequent company picnics.

Understanding the organization’s culture may start from observing its artifacts: its physical environment, employee interactions, company policies, reward systems, and other observable characteristics. When you are interviewing for a position, observing the physical environment, how people dress, where they relax, and how they talk to others is definitely a good start to understanding the company’s culture. However, simply looking at these tangible aspects is unlikely to give a full picture of the organization, since an important chunk of what makes up culture exists below one’s degree of awareness. The values and, deeper, the assumptions that shape the organization’s culture can be uncovered by observing how employees interact and the choices they make, as well as by inquiring about their beliefs and perceptions regarding what is right and appropriate behavior.

Key Takeaway

Organizational culture is a system of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs that helps individuals understand which behaviors are and are not appropriate within an organization. Cultures can be a source of competitive advantage for organizations. Strong organizational cultures can be an organizing as well as a controlling mechanism for organizations. And finally, organizational culture consists of three levels: assumptions that are below the surface, values, and artifacts.

Source: Why culture can mean life or death for your organization. (September, 2007). HR Focus, 84, 9.

Measuring Organizational Culture

Dimensions of Culture

Which values characterize an organization’s culture? Even though culture may not be immediately observable, identifying a set of values that might be used to describe an organization’s culture helps us identify, measure, and manage culture more effectively. For this purpose, several researchers have proposed various culture typologies. One typology that has received a lot of research attention is the Organizational Culture Profile (OCP) where culture is represented by seven distinct values (Chatman & Jehn, 1991; O’Reilly, et. al., 1991) (Figure 2).

Innovative Cultures

According to the OCP framework, companies that have innovative cultures are flexible, adaptable, and experiment with new ideas. These companies are characterized by a flat hierarchy and titles and other status distinctions tend to be downplayed. For example, W. L. Gore & Associates is a company with innovative products such as GORE-TEX® (the breathable fabric that is windproof and waterproof), Glade dental floss, and Elixir guitar strings, earning the company the distinction as the most innovative company in the United States by Fast Company magazine in 2004. W. L. Gore consistently manages to innovate and capture the majority of market share in a wide variety of industries, in large part because of its unique culture. In this company, employees do not have bosses in the traditional sense, and risk taking is encouraged by celebrating failures as well as successes (Deutschman, 2004). Companies such as W. L. Gore, Genentech, and Google also encourage their employees to take risks by allowing engineers to devote 20% of their time to projects of their own choosing.

Aggressive Cultures

Companies with aggressive cultures value competitiveness and outperforming competitors; by emphasizing this, they often fall short in corporate social responsibility. For example, Microsoft is often identified as a company with an aggressive culture. The company has faced a number of antitrust lawsuits and disputes with competitors over the years. In aggressive companies, people may use language such as “we will kill our competition.” In the past, Microsoft executives made statements such as “we are going to cut off Netscape’s air supply…Everything they are selling, we are going to give away,” and its aggressive culture is cited as a reason for getting into new legal troubles before old ones are resolved (Greene, et. al., 2004; Schlender, 1998) (Figure 3).

Outcome-Oriented Cultures

The OCP framework describes outcome-oriented cultures as those that emphasize achievement, results, and action as important values. A good example of an outcome-oriented culture may be the electronics retailer Best Buy. Having a culture emphasizing sales performance, Best Buy tallies revenues and other relevant figures daily by department. Employees are trained and mentored to sell company products effectively, and they learn how much money their department made every day (Copeland, 2004). In 2005, the company implemented a Results Oriented Work Environment (ROWE) program that allows employees to work anywhere and anytime; they are evaluated based on results and fulfillment of clearly outlined objectives (Thompson, 2005). Outcome-oriented cultures hold employees as well as managers accountable for success and use systems that reward employee and group output. In these companies, it is more common to see rewards tied to performance indicators as opposed to seniority or loyalty. Research indicates that organizations that have a performance-oriented culture tend to outperform companies that are lacking such a culture (Nohria, et. al., 2003). At the same time, when performance pressures lead to a culture where unethical behaviors become the norm, individuals see their peers as rivals, and short-term results are rewarded, the resulting unhealthy work environment serves as a liability (Probst & Raisch, 2005).

Stable Cultures

Stable cultures are predictable, rule-oriented, and bureaucratic. When the environment is stable and certain, these cultures may help the organization to be effective by providing stable and constant levels of output (Westrum, 2004). These cultures prevent quick action and, as a result, may be a misfit to a changing and dynamic environment. Public sector institutions may be viewed as stable cultures. In the private sector, Kraft Foods is an example of a company with centralized decision making and rule orientation that suffered as a result of the culture-environment mismatch (Thompson, 2006). Its bureaucratic culture is blamed for killing good ideas in early stages and preventing the company from innovating. When the company started a change program to increase the agility of its culture, one of its first actions was to fight bureaucracy with more bureaucracy: The new position of vice president of “business process simplification” was created but was later eliminated (Boyle, 2004; Thompson, 2005; Thompson, 2006).

People-Oriented Cultures

People-oriented cultures value fairness, supportiveness, and respecting individual rights. In these organizations, there is a greater emphasis on and expectation of treating people with respect and dignity (Erdogan, et. al., 2006). One study of new employees in accounting companies found that employees, on average, stayed 14 months longer in companies with people-oriented cultures (Sheridan, 1992). Starbucks is an example of a people-oriented culture. The company pays employees above minimum wage, offers health care and tuition reimbursement benefits to its part-time as well as full-time employees, and has creative perks such as weekly free coffee for all associates. As a result of these policies, the company benefits from a turnover rate lower than the industry average (Weber, 2005).

Team-Oriented Cultures

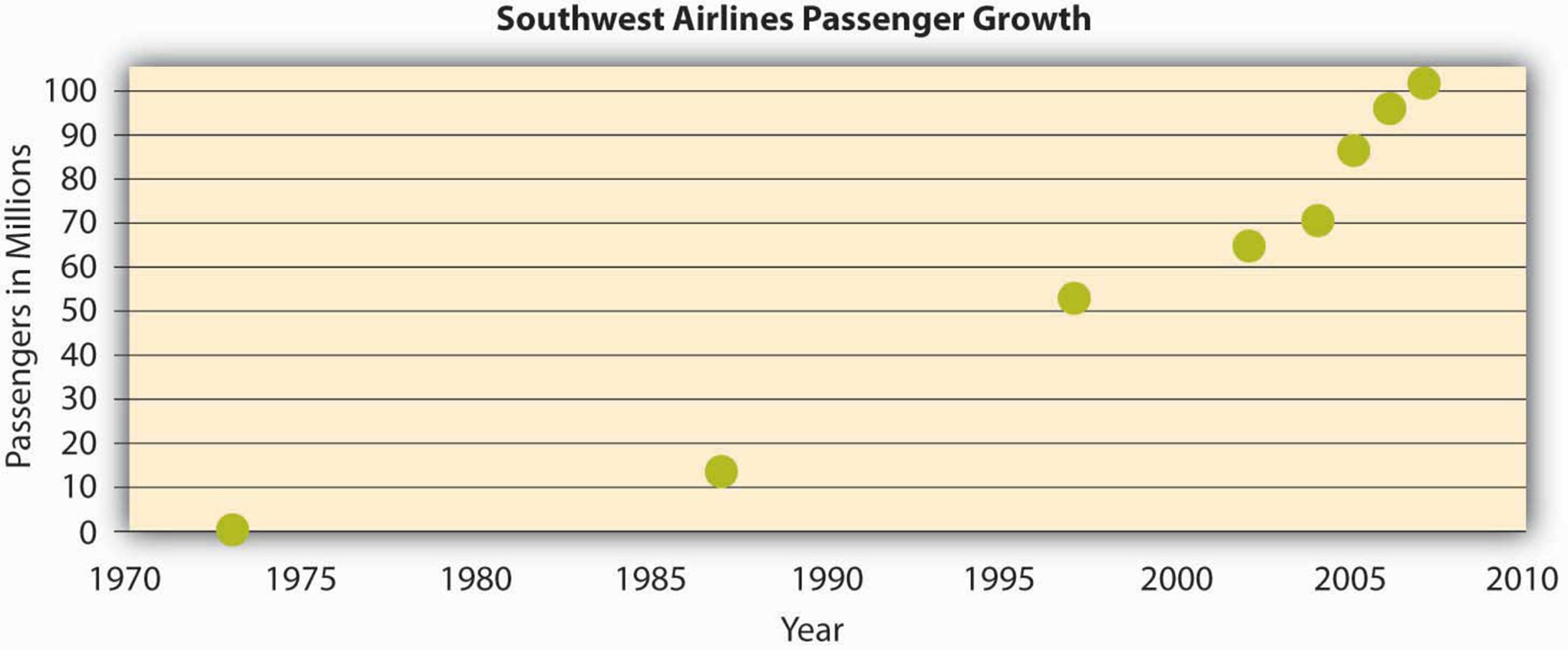

Companies with ateam-oriented culture are collaborative and emphasize cooperation among employees. For example, Southwest Airlines facilitates a team-oriented culture by cross-training its employees so that they are capable of helping one another when needed. The company also emphasizes training intact work teams (Bolino & Turnley, 2003). In Southwest’s selection process, applicants who are not viewed as team players are not hired as employees (Miles & Mangold, 2005) (Figure 4). In team-oriented organizations, members tend to have more positive relationships with their coworkers and particularly with their managers (Erdogan, et. al., 2006).

Detail-Oriented Cultures

Remember that, in the end, culture is really about people.

Organizations with a detail-oriented culture are characterized in the OCP framework as emphasizing precision and paying attention to details. Such a culture gives a competitive advantage to companies in the hospitality industry by helping them differentiate themselves from others. For example, Four Seasons and Ritz Carlton are among hotels who keep records of all customer requests such as which newspaper the guest prefers or what type of pillow the customer uses. This information is put into a computer system and used to provide better service to returning customers. Any requests hotel employees receive, as well as overhear, might be entered into the database to serve customers better (Figure 5).

Strength of Culture

A strong culture is one that is shared by organizational members (Figure 6) (Arogyaswamy & Byles, 1987; Chatman & Eunyoung, 2003) — that is, a culture in which most employees in the organization show consensus regarding the values of the company. The stronger a company’s culture, the more likely it is to affect the way employees think and behave. For example, cultural values emphasizing customer service will lead to higher-quality customer service if there is widespread agreement among employees on the importance of customer-service-related values (Schneider, et. al., 2002).

It is important to realize that a strong culture may act as an asset or a liability for the organization, depending on the types of values that are shared. For example, imagine a company with a culture that is strongly outcome-oriented. If this value system matches the organizational environment, the company may perform well and outperform its competitors. This is an asset as long as members are behaving ethically. However, a strong outcome-oriented culture coupled with unethical behaviors and an obsession with quantitative performance indicators may be detrimental to an organization’s effectiveness. Enron is an extreme example of this dysfunctional type of strong culture.

One limitation of a strong culture is the difficulty of changing it. In an organization where certain values are widely shared, if the organization decides to adopt a different set of values, unlearning the old values and learning the new ones will be a challenge because employees will need to adopt new ways of thinking, behaving, and responding to critical events. For example, Home Depot had a decentralized, autonomous culture where many business decisions were made using “gut feeling” while ignoring the available data. When Robert Nardelli became CEO of the company in 2000, he decided to change its culture starting with centralizing many of the decisions that were previously left to individual stores. This initiative met with substantial resistance, and many high-level employees left during Nardelli’s first year. Despite getting financial results such as doubling the sales of the company, many of the changes he made were criticized. He left the company in January 2007 (Charan, 2006; Herman & Wernle, 2007).

A strong culture may also be a liability during a merger. During mergers and acquisitions, companies inevitably experience a clash of cultures, as well as a clash of structures and operating systems. Culture clash becomes more problematic if both parties have unique and strong cultures. For example, during the merger of Daimler-Benz with Chrysler to create DaimlerChrysler, the differing strong cultures of each company acted as a barrier to effective integration. Daimler had a strong engineering culture that was more hierarchical and emphasized routinely working long hours. Daimler employees were used to being part of an elite organization, evidenced by flying first class on all business trips. However, Chrysler had a sales culture where employees and managers were used to autonomy, working shorter hours, and adhering to budget limits that meant only the elite flew first class. The different ways of thinking and behaving in these two companies introduced a number of unanticipated problems during the integration process (Badrtalei & Bates, 2007; Bower, 2001).

Do Organizations Have a Single Culture?

So far, we have assumed that a company has a single culture that is shared throughout the organization. In reality there might be multiple cultures within the organization. For example, people working on the sales floor may experience a different culture from that experienced by people working in the warehouse. Cultures that emerge within different departments, branches, or geographic locations are called subcultures. Subcultures may arise from the personal characteristics of employees and managers, as well as the different conditions under which work is performed. In addition to understanding the broader organization’s values, managers will need to make an effort to understand subculture values to see their effect on workforce behavior and attitudes.

Sometimes, a subculture may take the form of a counterculture. Defined as shared values and beliefs that are in direct opposition to the values of the broader organizational culture (Kerr, et. al., 2005), countercultures are often shaped around a charismatic leader. For example, within a largely bureaucratic organization, an enclave of innovativeness and risk taking may emerge within a single department. A counterculture may be tolerated by the organization as long as it is bringing in results and contributing positively to the effectiveness of the organization. However, its existence may be perceived as a threat to the broader organizational culture. In some cases, this may lead to actions that would take away the autonomy of the managers and eliminate the counterculture.

Key Takeaway

Culture can be understood in terms of seven different culture dimensions, depending on what is most emphasized within the organization. For example, innovative cultures are flexible, adaptable, and experiment with new ideas, while stable cultures are predictable, rule-oriented, and bureaucratic. Strong cultures can be an asset or liability for an organization but can be challenging to change. Multiple cultures may coexist in a single organization in the form of subcultures and countercultures.

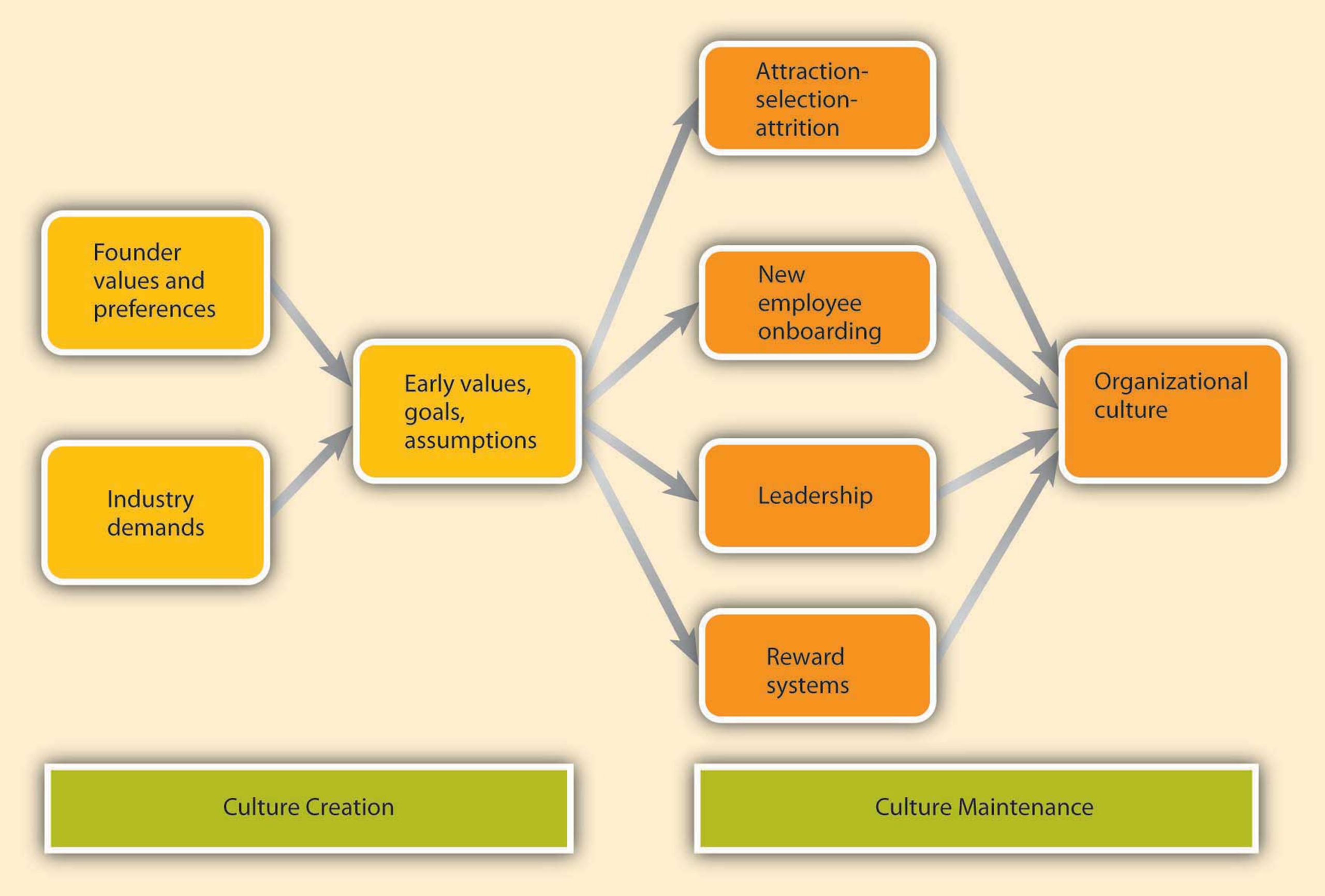

Creating and Maintaining Organizational Culture

How are cultures created? Where do cultures come from? Understanding this question is important in understanding how they can be changed. An organization’s culture is shaped as the organization faces external and internal challenges and learns how to deal with them (Figure 7). When the organization’s way of doing business provides a successful adaptation to environmental challenges and ensures success, those values are retained. These values and ways of doing business are taught to new members as the way to do business (Schein, 1992). The factors that are most important in the creation of an organization’s culture include founders’ values, preferences, and industry demands.

Founder Values

A company’s culture, particularly during its early years, is inevitably tied to the personality, background, and values of its founder or founders, as well as their vision for the future of the organization. When entrepreneurs establish their own businesses, the way they want to do business determines the organization’s rules, the structure set up in the company, and the people they hire to work with them. For example, some of the existing corporate values of the ice cream company Ben & Jerry’s Homemade Holdings Inc. can easily be traced to the personalities of its founders Ben Cohen and Jerry Greenfield (Figure 8). In 1978, the two high school friends opened up their first ice-cream shop in a renovated gas station in Burlington, Vermont. Their strong social convictions led them to buy only from the local farmers and devote a certain percentage of their profits to charities. The core values they instilled in their business can still be observed in the current company’s devotion to social activism and sustainability, its continuous contributions to charities, use of environmentally friendly materials, and dedication to creating jobs in low-income areas. Even though Unilever acquired the company in 2000, the social activism component remains unchanged and Unilever has expressed its commitment to maintaining it (Kiger, 2005; Rubis, et. al., 2005; Smalley, 2007).

Founder values become part of the corporate culture to the degree to which they help the company be successful. For example, the social activism of Ben and Jerry’s was instilled in the company because the founders strongly believed in these issues. However, these values probably would not be surviving 3 decades later if they had not helped the company in its initial stages. In the case of Ben and Jerry’s, these values helped distinguish their brand from larger corporate brands and attracted a loyal customer base. Thus, by providing a competitive advantage, these values were retained as part of the corporate culture and were taught to new members as the right way to do business.

Industry Demands

While founders undoubtedly exert a powerful influence over corporate cultures, the industry characteristics also play a role. Companies within the same industry can sometimes have widely differing cultures. At the same time, the industry characteristics and demands act as a force to create similarities among organizational cultures. For example, despite some differences, many companies in the insurance and banking industries are stable and rule-oriented, many companies in the high-tech industry have innovative cultures, and those in nonprofit industry may be people-oriented. If the industry is one with a large number of regulatory requirements — for example, banking, health care, and high-reliability (such as nuclear power plant) industries — then we might expect the presence of a large number of rules and regulations, a bureaucratic company structure, and a stable culture. The industry influence over culture is also important to know because this shows that it may not be possible to imitate the culture of a company in a different industry, even though it may seem admirable to outsiders.

How Are Cultures Maintained?

As a company matures, its cultural values are refined and strengthened. The early values of a company’s culture exert influence over its future values. It is possible to think of organizational culture as an organism that protects itself from external forces. Organizational culture determines what types of people are hired by an organization and what types of people are left out. Moreover, once new employees are hired, the company assimilates new employees and teaches them the way things are done in the organization. We call these processesattraction-selection-attrition and onboarding processes. We will also examine the role of leaders and reward systems in shaping and maintaining an organization’s culture.

Attraction-Selection-Attrition

Organizational culture is maintained through a process known as attraction-selection-attrition (ASA). First, employees are attracted to organizations where they will fit in. Someone who has a competitive nature may feel comfortable in and may prefer to work in a company where interpersonal competition is the norm. Others may prefer to work in a team-oriented workplace. Research shows that employees with different personality traits find different cultures attractive. For example, out of the Big Five personality traits, employees who demonstrate neurotic personalities were less likely to be attracted to innovative cultures, whereas those who had openness to experience were more likely to be attracted to innovative cultures (Judge & Cable, 1997).

Of course, this process is imperfect, and value similarity is only one reason a candidate might be attracted to a company. There may be other, more powerful attractions such as good benefits. At this point in the process, the second component of the ASA framework prevents them from getting in: selection. Just as candidates are looking for places where they will fit in, companies are also looking for people who will fit into their current corporate culture. Many companies are hiring people for fit with their culture, as opposed to fit with a certain job. For example, Southwest Airlines prides itself for hiring employees based on personality and attitude rather than specific job-related skills, which they learn after they are hired. Companies use different techniques to weed out candidates who do not fit with corporate values. For example, Google relies on multiple interviews with future peers. By introducing the candidate to several future coworkers and learning what these coworkers think of the candidate, it becomes easier to assess the level of fit.

Even after a company selects people for person-organization fit, there may be new employees who do not fit in. Some candidates may be skillful in impressing recruiters and signal high levels of culture fit even though they do not necessarily share the company’s values. In any event, the organization is eventually going to eliminate candidates eventually who do not fit in through attrition. Attrition refers to the natural process where the candidates who do not fit in will leave the company. Research indicates that person-organization misfit is one of the important reasons for employee turnover (Kristof-Brown, et. al., 2005; O’Reilly, et. al., 1991).

Because of the ASA process, the company attracts, selects, and retains people who share its core values, whereas those people who are different in core values will be excluded from the organization either during the hiring process or later on through naturally occurring turnover. Thus, organizational culture will act as a self-defending organism where intrusive elements are kept out. Supporting the existence of such self-protective mechanisms, research shows that organizations demonstrate a certain level of homogeneity regarding personalities and values of organizational members (Giberson, et. al., 2005).

New Employee Onboarding

Another way in which an organization’s values, norms, and behavioral patterns are transmitted to employees is through onboarding (also referred to as the organizational socialization process). Onboarding refers to the process through which new employees learn the attitudes, knowledge, skills, and behaviors required to function effectively within an organization. If an organization can successfully socialize new employees into becoming organizational insiders, new employees will feel accepted by their peers and confident regarding their ability to perform; they will also understand and share the assumptions, norms, and values that are part of the organization’s culture. This understanding and confidence in turn translate into more effective new employees who perform better and have higher job satisfaction, stronger organizational commitment, and longer tenure within the company (Bauer, et. al., 2007). Organizations engage in different activities to facilitate onboarding, such as implementing orientation programs or matching new employees with mentors.

What Can Employees Do During Onboarding?

New employees who are proactive, seek feedback, and build strong relationships tend to be more successful than those who do not (Bauer & Green, 1998; Kammeyer-Mueller & Wanberg, 2003; Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). For example,feedback seeking helps new employees. Especially on a first job, a new employee can make mistakes or gaffes and may find it hard to understand and interpret the ambiguous reactions of coworkers. By actively seeking feedback, new employees may find out sooner rather than later any behaviors that need to be changed and gain a better understanding of whether their behavior fits with the company culture and expectations.

Relationship building or networking (a facet of the organizing function) is another important behavior new employees may demonstrate. Particularly when a company does not have a systematic approach to onboarding, it becomes more important for new employees to facilitate their own onboarding by actively building relationships. According to one estimate, 35% of managers who start a new job fail in the new job and either voluntarily leave or are fired within one and a half years. Of these, over 60% report not being able to form effective relationships with colleagues as the primary reason for this failure (Fisher, 2005).

What Can Organizations Do During Onboarding?

Many organizations, including Microsoft, Kellogg Company, and Bank of America take a more structured and systematic approach to new employee onboarding, while others follow a “sink or swim” approach where new employees struggle to figure out what is expected of them and what the norms are.

A formal orientation program indoctrinates new employees to the company culture, as well as introducing them to their new jobs and colleagues. An orientation program has a role in making new employees feel welcome in addition to imparting information that may help them be successful in their new jobs. Many large organizations have formal orientation programs consisting of lectures, videotapes, and written material, while some may follow more informal approaches. According to one estimate, most orientations last anywhere from one to five days, and some companies are currently switching to a computer-based orientation. Ritz Carlton, the company ranked number 1 in Training magazine’s 2007 top 125 list, uses a very systematic approach to employee orientation and views orientation as the key to retention. In the 2-day classroom orientation, employees spend time with management, dine in the hotel’s finest restaurant, and witness the attention to customer service detail firsthand. During these two days, they are introduced to the company’s intensive service standards, team orientation, and its own language. Later, on their 21st day they are tested on the company’s service standards and are certified (Durett, 2006; Elswick, 2000). Research shows that formal orientation programs are helpful in teaching employees about the goals and history of the company, as well as communicating the power structure. Moreover, these programs may also help with a new employee’s integration to the team. However, these benefits may not be realized to the same extent in computer-based orientations. In fact, compared to those taking part in a regular, face-to-face orientation, those undergoing a computer-based orientation were shown to have lower understanding of their job and the company, indicating that different formats of orientations may not substitute for each other (Klein & Weaver, 2000; Moscato, 2005; Wesson & Gogus, 2005).

What Can Organizational Insiders Do During Onboarding?

One of the most important ways in which organizations can help new employees adjust to a company and a new job is through organizational insiders — namely, supervisors, coworkers, and mentors. Leaders have a key influence over onboarding and the information and support they provide determine how quickly employees learn about the company politics and culture, while coworker influence determines the degree to which employees adjust to their teams. Mentors can be crucial to helping new employees adjust by teaching them the ropes of their jobs and how the company really operates. A mentor is a trusted person who provides an employee with advice and support regarding career-related matters. Although a mentor can be any employee or manager who has insights that are valuable to the new employee, mentors tend to be relatively more experienced than their protégés. Mentoring can occur naturally between two interested individuals or organizations can facilitate this process by having formal mentoring programs. These programs may successfully bring together mentors and protégés who would not come together otherwise. Research indicates that the existence of these programs does not guarantee their success, and there are certain program characteristics that may make these programs more effective. For example, when mentors and protégés feel that they had input in the mentor-protégé matching process, they tend to be more satisfied with the arrangement. Moreover, when mentors receive training beforehand, the outcomes of the program tend to be more positive (Allen, et. al., 2006). Because mentors may help new employees interpret and understand the company’s culture, organizations may benefit from selecting mentors who personify the company’s values. Thus, organizations may need to design these programs carefully to increase their chance of success.

Leadership

Leaders are instrumental in creating and changing an organization’s culture. There is a direct correspondence between the leader’s style and an organization’s culture. For example, when leaders motivate employees through inspiration, corporate culture tends to be more supportive and people-oriented. When leaders motivate by making rewards contingent on performance, the corporate culture tended to be more performance-oriented and competitive (Sarros, et. al., 2002). In these and many other ways, what leaders do directly influences the cultures of their organizations. This is a key point for managers to consider as they carry out their leading P-O-L-C function.

Part of the leader’s influence over culture is through role modeling. Many studies have suggested that leader behavior, the consistency between organizational policy and leader actions, and leader role modeling determine the degree to which the organization’s culture emphasizes ethics (Driscoll & McKee, 2007). The leader’s own behaviors will signal to individuals what is acceptable behavior and what is unacceptable. In an organization in which high-level managers make the effort to involve others in decision making and seek opinions of others, a team-oriented culture is more likely to evolve. By acting as role models, leaders send signals to the organization about the norms and values that are expected to guide the actions of its members.

Leaders also shape culture by their reactions to the actions of others around them. For example, do they praise a job well done or do they praise a favored employee regardless of what was accomplished? How do they react when someone admits to making an honest mistake? What are their priorities? In meetings, what types of questions do they ask? Do they want to know what caused accidents so that they can be prevented, or do they seem more concerned about how much money was lost because of an accident? Do they seem outraged when an employee is disrespectful to a coworker, or does their reaction depend on whether they like the harasser? Through their day-to-day actions, leaders shape and maintain an organization’s culture.

Reward Systems

Finally, the company culture is shaped by the type of reward systems used in the organization and the kinds of behaviors and outcomes it chooses to reward and punish. One relevant element of the reward system is whether the organization rewards behaviors or results. Some companies have reward systems that emphasize intangible elements of performance as well as more easily observable metrics. In these companies, supervisors and peers may evaluate an employee’s performance by assessing the person’s behaviors as well as the results. In such companies, we may expect a culture that is relatively people- or team-oriented, and employees act as part of a family (Kerr & Slocum, 2005). However, in companies in which goal achievement is the sole criterion for reward, there is a focus on measuring only the results without much regard to the process. In these companies, we might observe outcome-oriented and competitive cultures. Whether the organization rewards performance or seniority would also make a difference in culture. When promotions are based on seniority, it would be difficult to establish a culture of outcome orientation. Finally, the types of behaviors that are rewarded or ignored set the tone for the culture. Which behaviors are rewarded, which ones are punished, and which are ignored will determine how a company’s culture evolves. A reward system is one tool managers can wield when undertaking the controlling function.

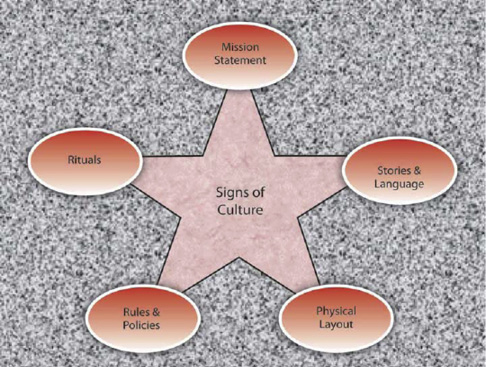

Signs of Organizational Culture

How do you find out about a company’s culture? We emphasized earlier that culture influences the way members of the organization think, behave, and interact with one another. Thus, one way of finding out about a company’s culture is by observing employees or interviewing them. At the same time, culture manifests itself in some visible aspects of the organization’s environment. In this section, we discuss five ways in which culture shows itself to observers and employees.

Visual Elements of Culture

Mission Statement

A mission statement is a statement of purpose, describing who the company is and what it does (Figure 9). It serves an important function for organizations as part of the first facet of the planning P-O-L-C function. But, while many companies have mission statements, they do not always reflect the company’s values and its purpose. An effective mission statement is well known by employees, is transmitted to all employees starting from their first day at work, and influences employee behavior.

Some mission statements reflect who the company wants to be as opposed to who they actually are. If the mission statement does not affect employee behavior on a day-to-day basis, it has little usefulness as a tool for understanding the company’s culture. Enron provided an often-cited example of a disconnect between a company’s mission statement and how the company actually operated. Their missions and values statement started with “As a partner in the communities in which we operate, Enron believes it has a responsibility to conduct itself according to certain basic principles.” Their values statement included such ironic declarations as “We do not tolerate abusive or disrespectful treatment. Ruthlessness, callousness and arrogance don’t belong here (Kunen, 2002).”

A mission statement that is taken seriously and widely communicated may provide insights into the corporate culture. For example, the Mayo Clinic’s mission statement is “The needs of the patient come first.” This mission statement evolved from the founders who are quoted as saying, “The best interest of the patient is the only interest to be considered.” Mayo Clinics have a corporate culture that puts patients first. For example, no incentives are given to physicians based on the number of patients they see. Because doctors are salaried, they have no interest in retaining a patient for themselves, and they refer the patient to other doctors when needed (Jarnagin & Slocum, 2007). Wal-Mart may be another example of a company that lives its mission statement and therefore its mission statement may give hints about its culture: “Saving people money so they can live better (Wal-Mart, 2008).”

Rituals

Rituals refer to repetitive activities within an organization that have symbolic meaning (Anand, 2005). Usually rituals have their roots in the history of a company’s culture. They create camaraderie and a sense of belonging among employees. They also serve to teach employees corporate values and create identification with the organization. For example, at the cosmetics firm Mary Kay Inc., employees attend ceremonies recognizing their top salespeople with an award of a new car — traditionally a pink Cadillac (Figure 10). These ceremonies are conducted in large auditoriums where participants wear elaborate evening gowns and sing company songs that create emotional excitement. During this ritual, employees feel a connection to the company culture and its values such as self-determination, willpower, and enthusiasm (Jarnagin & Slocum, 2007). Another example of rituals is the Saturday morning meetings of Wal-Mart. This ritual was first created by the company founder Sam Walton, who used these meetings to discuss which products and practices were doing well and which required adjustment. He was able to use this information to make changes in Wal-Mart’s stores before the start of the week, which gave him a competitive advantage over rival stores who would make their adjustments based on weekly sales figures during the middle of the following week. Today, hundreds of Wal-Mart associates attend the Saturday morning meetings in the Bentonville, Arkansas, headquarters. The meetings, which run from 7:00 a.m. to 9:30 a.m., start and end with the Wal-Mart cheer; the agenda includes a discussion of weekly sales figures and merchandising tactics. As a ritual, the meetings help maintain a small-company atmosphere, ensure employee involvement and accountability, communicate a performance orientation, and demonstrate taking quick action (Schlender, 2005).

Rules and Policies

Another way in which an observer may find out about a company’s culture is to examine its rules and policies. Companies create rules to determine acceptable and unacceptable behavior and, thus, the rules that exist in a company will signal the type of values it has. Policies about issues such as decision making, human resources, and employee privacy reveal what the company values and emphasizes. For example, a company that has a policy such as “all pricing decisions of merchandise will be made at corporate headquarters” is likely to have a centralized culture that is hierarchical, as opposed to decentralized and empowering. The presence or absence of policies on sensitive issues such as English-only rules, bullying and unfair treatment of others, workplace surveillance, open-door policies, sexual harassment, workplace romances, and corporate social responsibility all provide pieces of the puzzle that make up a company’s culture. This highlights how interrelated the P-O-L-C functions are in practice. Through rules and policies, the controlling function affects the organization’s culture, a facet of organizing.

Impact of HR Practices on Organizational Culture

Below are scenarios of critical decisions you may need to make as a manager one day. Read each question and select one response from each pair of statements. Then, think about the effect your choice would have on the company’s culture (your organizing function) as well as on your controlling function.

- Your company needs to lay off 10 people. Would you

- lay off the newest 10 people?

- lay off the 10 people who have the lowest performance evaluations?

- You’re asked to establish a dress code. Would you

- ask employees to use their best judgment?

- create a detailed dress code highlighting what is proper and improper?

- You need to monitor employees during work hours. Would you

- not monitor them because they are professionals and you trust them?

- install a program monitoring their Web usage to ensure that they are spending work hours actually doing work?

- You’re preparing performance appraisals. Would you

- evaluate people on the basis of their behaviors?

- evaluate people on the basis of the results (numerical sales figures, etc.)?

- Who will be promoted? Would you promote individuals based on

- seniority?

- objective performance?

Physical Layout

A company’s building, layout of employee offices, and other workspaces communicate important messages about a company’s culture. For example, visitors walking into the Nike campus in Beaverton, Oregon, can witness firsthand some of the distinguishing characteristics of the company’s culture. The campus is set on 74 acres and boasts an artificial lake, walking trails, soccer fields, and cutting-edge fitness centers. The campus functions as a symbol of Nike’s values such as energy, physical fitness, an emphasis on quality, and a competitive orientation. In addition, at fitness centers on the Nike headquarters, only those using Nike shoes and apparel are allowed in. This sends a strong signal that loyalty is expected. The company’s devotion to athletes and their winning spirit are manifested in campus buildings named after famous athletes, photos of athletes hanging on the walls, and their statues dotting the campus (Capowski, 1993; Collins & Porras, 1996 Labich & Carvell, 1995; Mitchell, 2002).

The layout of the office space also is a strong indicator of a company’s culture. A company that has an open layout where high-level managers interact with employees may have a culture of team orientation and egalitarianism, whereas a company where most high-level managers have their own floor may indicate a higher level of hierarchy. Microsoft employees tend to have offices with walls and a door because the culture emphasizes solitude, concentration, and privacy. In contrast, Intel is famous for its standard cubicles, which reflect its egalitarian culture. The same value can also be observed in its avoidance of private and reserved parking spots (Clark, 2007). The degree to which playfulness, humor, and fun are part of a company’s culture may be indicated in the office environment. For example, Jive Software boasts a colorful, modern, and comfortable office design. Their break room is equipped with a keg of beer, free snacks and sodas, an Xbox 360, and Nintendo Wii. A casual observation of their work environment sends the message that employees who work there see their work as fun (Jive Software, 2008).

Stories and Language

Perhaps the most colorful and effective way in which organizations communicate their culture to new employees and organizational members is through the skillful use of stories. A story can highlight a critical event an organization faced and the organization’s response to it, or a heroic effort of a single employee illustrating the company’s values. The stories usually engage employee emotions and generate employee identification with the company or the heroes of the tale. A compelling story may be a key mechanism through which managers motivate employees by giving their behavior direction and by energizing them toward a certain goal (Beslin, 2007). Moreover, stories shared with new employees communicate the company’s history, its values and priorities, and create a bond between the new employee and the organization. For example, you may already be familiar with the story of how a scientist at 3M invented Post-it notes. Arthur Fry, a 3M scientist, was using slips of paper to mark the pages of hymns in his church choir, but they kept falling off. He remembered a superweak adhesive that had been invented in 3M’s labs, and he coated the markers with this adhesive. Thus, the Post-it notes were born. However, marketing surveys for the interest in such a product were weak and the distributors were not convinced that it had a market. Instead of giving up, Fry distributed samples of the small yellow sticky notes to secretaries throughout his company. Once they tried them, people loved them and asked for more. Word spread and this led to the ultimate success of the product. As you can see, this story does a great job of describing the core values of a 3M employee: Being innovative by finding unexpected uses for objects, persevering, and being proactive in the face of negative feedback (Higgins & McAllester, 2002).

Language is another way to identify an organization’s culture. Companies often have their own acronyms and buzzwords that are clear to them and help set apart organizational insiders from outsiders. In business, this code is known as jargon. Jargon is the language of specialized terms used by a group or profession. Every profession, trade, and organization has its own specialized terms.

Key Takeaway

Organizational cultures are created by a variety of factors, including founders’ values and preferences, industry demands, and early values, goals, and assumptions. Culture is maintained through attraction-selection-attrition, new employee onboarding, leadership, and organizational reward systems. Signs of a company’s culture include the organization’s mission statement, stories, physical layout, rules and policies, and rituals.

Exercises

- Do you think it is a good idea for companies to emphasize person-organization fit when hiring new employees? What advantages and disadvantages do you see when hiring people who fit with company values?

- What is the influence of company founders on company culture? Give examples based on your personal knowledge.

- What are the methods companies use to aid with employee onboarding? What is the importance of onboarding for organizations?

- What type of a company do you feel you would fit in? What type of a culture would be a misfit for you? In your past work experience, were there any moments when you felt that you did not fit in? Why?

- What is the role of physical layout as an indicator of company culture? What type of a physical layout would you expect from a company that is people-oriented? Team-oriented? Stable?

References

Arogyaswamy, B., & Byles, C. H. (1987). Organizational culture: Internal and external fits. Journal of Management, 13, 647–658.

Barney, J. B. (1986). Organizational culture: Can it be a source of sustained competitive advantage? Academy of Management Review, 11, 656–665.

Chatman, J. A., & Eunyoung Cha, S. (2003). Leading by leveraging culture. California Management Review, 45, 19–34.

Kotter, J. P., & Heskett, J. L. (1992). Corporate Culture and Performance. New York: Free Press.

Marcoulides, G. A., & Heck, R. H. (1993, May). Organizational culture and performance: Proposing and testing a model. Organizational Science, 4, 209–225.

Schein, E. H. (1992). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Slocum, J. W. (2005). Managing corporate culture through reward systems. Academy of Management Executive, 19, 130–138.

Badrtalei, J., & Bates, D. L. (2007). Effect of organizational cultures on mergers and acquisitions: The case of DaimlerChrysler. International Journal of Management, 24, 303–317.

Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. (2003). Going the extra mile: Cultivating and managing employee citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Executive, 17, 60–71.

Bower, J. L. (2001). Not all M&As are alike — and that matters. Harvard Business Review, 79, 92–101.

Boyle, M. (2004, November 15). Kraft’s arrested development. Fortune, 150, 144.

Charan, R. (2006, April). Home Depot’s blueprint for culture change. Harvard Business Review, 84, 60–70.

Chatman, J. A., & Eunyoung Cha, S. (2003). Leading by leveraging culture. California Management Review, 45, 20–34.

Chatman, J. A., & Jehn, K. A. (1991). Assessing the relationship between industry characteristics and organizational culture: How different can you be? Academy of Management Journal, 37, 522–553.

Copeland, M. V. (2004, July). Best Buy’s selling machine. Business 2.0, 5, 92–102.

Deutschman, A. (2004, December). The fabric of creativity. Fast Company, 89, 54–62.

Erdogan, B., Liden, R. C., & Kraimer, M. L. (2006). Justice and leader-member exchange: The moderating role of organizational culture. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 395–406.

Greene, J., Reinhardt, A., & Lowry, T. (2004, May 31). Teaching Microsoft to make nice? Business Week, 3885, 80–81.

Herman, J., & Wernle, B. (2007, August 13). The book on Bob Nardelli: Driven, demanding. Automotive News, 81, 42.

Kerr, J., & Slocum, J. W., Jr. (2005). Managing corporate culture through reward systems. Academy of Management Executive, 19, 130–138.

Miles, S. J., & Mangold, G. (2005). Positioning Southwest Airlines through employee branding. Business Horizons, 48, 535–545.

Nohria, N., Joyce, W., & Roberson, B. (2003, July). What really works. Harvard Business Review, 81, 42–52.

O’Reilly, C. A., III, Chatman, J. A., & Caldwell, D. F. (1991). People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 487–516.

Probst, G., & Raisch, S. (2005). Organizational crisis: The logic of failure. Academy of Management Executive, 19, 90–105.

Schlender, B. (1998, June 22). Gates’s crusade. Fortune, 137, 30–32.

Schneider, B., Salvaggio, A., & Subirats, M. (2002). Climate strength: A new direction for climate research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 220–229.

Sheridan, J. (1992). Organizational culture and employee retention. Academy of Management Journal, 35, 1036–1056.

Thompson, J. (2005, September). The time we waste. Management Today, 44–47.

Thompson, S. (2005, February 28). Kraft simplification strategy anything but. Advertising Age, 76, 3–63.

Thompson, S. (2006, September 18). Kraft CEO slams company, trims marketing staff. Advertising Age, 77, 3–62.

Weber, G. (2005, February). Preserving the counter culture. Workforce Management, 84, 28–34; Motivation secrets of the 100 best employers. (2003, October). HR Focus, 80, 1–15.

Westrum, R. (2004, August). Increasing the number of guards at nuclear power plants. Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 24, 959–961.

Allen, T. D., Eby, L. T., & Lentz, E. (2006). Mentorship behaviors and mentorship quality associated with formal mentoring programs: Closing the gap between research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 567–578.

Anand, N. (2005). Blackwell Encyclopedic Dictionary of Management. Cambridge: Wiley.Bauer, T. N., & Green, S. G. (1998). Testing the combined effects of newcomer information seeking and manager behavior on socialization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 72–83.

Bauer, T. N., Bodner, T., Erdogan, B., Truxillo, D. M., & Tucker, J. S. (2007). Newcomer adjustment during organizational socialization: A meta-analytic review of antecedents, outcomes, and methods. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 707–721.

Beslin, R. (2007). Story building: A new tool for engaging employees in setting direction. Ivey Business Journal, 71, 1–8.

Capowski, G. S. (1993, June) Designing a corporate identity. Management Review, 82, 37–41; Collins, J., &.

Clark, D. (2007, October 15). Why Silicon Valley is rethinking the cubicle office. Wall Street Journal, 250, B9.

Driscoll, K., & McKee, M. (2007). Restorying a culture of ethical and spiritual values: A role for leader storytelling. Journal of Business Ethics, 73, 205–217.

Durett, J. (2006, March 1). Technology opens the door to success at Ritz-Carlton. Retrieved November 15, 2008, from http://www.managesmarter.com/msg/search/article_display.jsp?vnu_content_id=1002157749.

Elswick, J. (2000, February). Puttin’ on the Ritz: Hotel chain touts training to benefit its recruiting and retention. Employee Benefit News, 14, 9; The Ritz-Carlton Company: How it became a “legend” in service. (2001, January–February). Corporate University Review, 9, 16.

Fisher, A. (2005, March 7). Starting a new job? Don’t blow it. Fortune, 151, 48.

Giberson, T. R., Resick, C. J., & Dickson, M. W. (2005). Embedding leader characteristics: An examination of homogeneity of personality and values in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1002–1010.

Higgins, J. M., & McAllester, C. (2002) Want innovation? Then use cultural artifacts that support it. Organizational Dynamics, 31, 74–84.

Jarnagin, C., & Slocum, J. W., Jr. (2007). Creating corporate cultures through mythopoetic leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 36, 288–302.

Jive Software. (2008). Careers. Retrieved November 20, 2008, from http://www.jivesoftware.com/company.

Judge, T. A., & Cable, D. M. (1997). Applicant personality, organizational culture, and organization attraction. Personnel Psychology, 50, 359–394.

Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., & Wanberg, C. R. (2003). Unwrapping the organizational entry process: Disentangling multiple antecedents and their pathways to adjustment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 779–794.

Kerr, J., & Slocum, J. W., Jr. (2005). Managing corporate culture through reward systems. Academy of Management Executive, 19, 130–138.

Kiger, P. J. (April, 2005). Corporate crunch. Workforce Management, 84, 32–38.

Klein, H. J., & Weaver, N. A. (2000). The effectiveness of an organizational level orientation training program in the socialization of new employees. Personnel Psychology, 53, 47–66.

Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: a meta-analysis of person–job, person–organization, person–group, and person–supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58, 281–342.

Kunen, J. S. (2002, January 19). Enron’s vision (and values) thing. The New York Times, 19.

Labich, K., & Carvell, T. (1995, September 18). Nike vs. Reebok. Fortune, 132, 90–114.

Mitchell, C. (2002). Selling the brand inside. Harvard Business Review, 80, 99–105.

Moscato, D. (2005, April). Using technology to get employees on board. HR Magazine, 50, 107–109.

O’Reilly, C. A., III, Chatman, J. A., & Caldwell, D. F. (1991). People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 487–516.

Porras, J. I. (1996). Building your company’s vision. Harvard Business Review, 74, 65–77.

Rubis, L., Fox, A., Pomeroy, A., Leonard, B., Shea, T. F., Moss, D., et al. (2005). 50 for history. HR Magazine, 50, 13, 10–24.

Sarros, J. C., Gray, J., & Densten, I. L. (2002). Leadership and its impact on organizational culture. International Journal of Business Studies, 10, 1–26.

Schein, E. H. (1992). Organizational Culture and Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schlender, B. (2005, April 18). Wal-Mart’s $288 billion meeting. Fortune, 151, 90–106; Wal around the world. (2001, December 8). Economist, 361, 55–57.

Smalley, S. (2007, December 3). Ben & Jerry’s bitter crunch. Newsweek, 150, 50.

Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. (2008). Investor frequently asked questions. Retrieved November 20, 2008, from http://walmartstores.com/Investors/7614.aspx.

Wanberg, C. R., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2000). Predictors and outcomes of proactivity in the socialization process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 373–385.

Wesson, M. J., & Gogus, C. I. (2005). Shaking hands with a computer: An examination of two methods of organizational newcomer orientation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1018–1026.

Barron, J. (2007, January). The HP way: Fostering an ethical culture in the wake of scandal. Business Credit, 109, 8–10.Gerstner, L. V. (2002). Who says elephants can’t dance? New York: HarperCollins.

Higgins, J., & McAllester, C. (2004). If you want strategic change, don’t forget to change your cultural artifacts. Journal of Change Management, 4, 63–73.

Kark, R., & Van Dijk, D. (2007). Motivation to lead, motivation to follow: The role of the self-regulatory focus in leadership processes. Academy of Management Review, 32, 500–528.

McGregor, J., McConnon, A., Weintraub, A., Holmes, S., & Grover, R. (2007, May 14). The 25 Most Innovative Companies. Business Week, 4034, 52–60.

Schein, E. H. (1990). Organizational culture. American Psychologist, 45, 109–119.

Daniel, L., & Brandon, C. (2006). Finding the right job fit. HR Magazine, 51, 62–67.

Sacks, D. (2005). Cracking your next company’s culture. Fast Company, 99, 85–87.

Ambrose, M. L., & Cropanzano, R. S. (2000). The effect of organizational structure on perceptions of procedural fairness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 294–304.

Brazil, J. J. (2007, April). Mission: Impossible? Fast Company, 114, 92–109.

Burns, T., & Stalker, M. G. (1961). The Management of Innovation. London: Tavistock.

Charan, R. (2006, April). Home Depot’s blueprint for culture change. Harvard Business Review, 84(4), 60–70.

Chonko, L. B. (1982). The relationship of span of control to sales representatives’ experienced role conflict and role ambiguity. Academy of Management Journal, 25, 452–456.

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1988) The influence of organizational structure. Journal of Management Studies, 25, 217–234.Fredrickson, J. W. (1986). The strategic decision process and organizational structure. Academy of Management Review, 11, 280–297.

Ghiselli, E. E., & Johnson, D. A. (1970). Need satisfaction, managerial success, and organizational structure. Personnel Psychology, 23, 569–576.

Hollenbeck, J. R., Moon, H., Ellis, A. P. J., West, B. J., Ilgen, D. R., et al. (2002). Structural contingency theory and individual differences: Examination of external and internal person-team fit. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 599–606.

Marquez, J. (2007, January 15). Big bucks at door for Depot HR leader. Workforce Management, 86(1).

Miller, D., Droge, C., & Toulouse, J. (1988). Strategic process and content as mediators between organizational context and structure. Academy of Management Journal, 31, 544–569.

Nelson, G. L., & Pasternack, B. A. (2005). Results: Keep what’s good, fix what’s wrong, and unlock great performance. New York: Crown Business.

Oldham, G. R., & Hackman, R. J. (1981). Relationships between organizational structure and employee reactions: Comparing alternative frameworks. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26, 66–83.

Pierce, J. L., & Delbecq, A. L. (1977). Organization structure, individual attitudes, and innovation. Academy of Management Review, 2, 27–37.

Porter, L. W., & Lawler, E. E. (1964). The effects of tall versus flat organization structures on managerial job satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 17, 135–148.

Porter, L. W., & Siegel, J. (2006). Relationships of tall and flat organization structures to the satisfactions of foreign managers. Personnel Psychology, 18, 379–392.

Schminke, M., Ambrose, M. L., & Cropanzano, R. S. (2000). The effect of organizational structure on perceptions of procedural fairness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 294–304.

Schollhammer, H. (1982). Internal corporate entrepreneurship. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Sherman, J. D., & Smith, H. L. (1984). The influence of organizational structure on intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation. Academy of Management Journal, 27, 877–885.

Sine, W. D., Mitsuhashi, H., & Kirsch, D. A. (2006). Revisiting Burns and Stalker: Formal structure and new venture performance in emerging economic sectors. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 121–132.

Slevin, D. P. (1988). The influence of organizational structure. Journal of Management Studies. 25, 217–234.

Slevin, D. P., & Covin, J. G. (1990). Juggling entrepreneurial style and organizational structure — how to get your act together. Sloan Management Review, 31(2), 43–53.

Turban, D. B., & Keon, T. L. (1993). Organizational attractiveness: An interactionist perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 184–193.

Wally, S., & Baum, J. R. (1994). Personal and structural determinants of the pace of strategic decision making. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 932–956.

Wally, S., & Baum, R. J. (1994). Strategic decision speed and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 24, 1107–1129.

Anand, N., & Daft, R. L. (2007). What is the right organization design? Organizational Dynamics, 36(4), 329–344.

Ashkenas, R., Ulrich, D., Jick, T., & Kerr, S. (1995). The Boundaryless organization: Breaking the chains of organizational structure. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Dess, G. G., Rasheed, A. M. A., McLaughlin, K. J., & Priem, R. L. (1995). The new corporate architecture. Academy of Management Executive, 9(3), 7–18.

Deutschman, A. (2005, March). Building a better skunk works. Fast Company, 92, 68–73.

Ford, R. C., & Randolph, W. A. (1992). Cross-functional structures: A review and integration of matrix organization and project management. Journal of Management, 18, 267–294.

Garvin, D. A. (1993, July/August). Building a learning organization. Harvard Business Review, 71(4), 78–91.

Joyce, W. F. (1986). Matrix organization: A social experiment. Academy of Management Journal, 29, 536–561.

Rosenbloom, B. (2003). Multi-channel marketing and the retail value chain. Thexis, 3, 23–26.

Anonymous. (December 2007). Change management: The HR strategic imperative as a business partner. HR Magazine, 52(12).

Anonymous. Moore’s Law. Retrieved September 5, 2008, from Answers.com, http://www.answers.com/topic/moore-s-law.

Ashford, S. J., Lee, C. L., & Bobko, P. (1989). Content, causes, and consequences of job insecurity: A theory-based measure and substantive test. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 803–829.

Barnett, W. P., & Carroll, G. R. (1995). Modeling internal organizational change. Annual Review of Sociology, 21, 217–236.

Boeker, W. (1997). Strategic change: The influence of managerial characteristics and organizational growth. Academy of Management Journal, 40, 152–170.

Deutschman, A. (2005, March). Building a better skunk works. Fast Company, 92, 68–73.

Diamond, J. (2005). Guns, germs, and steel: The fates of human societies. New York: W. W. Norton.

Fedor, D. M., Caldwell, S., & Herold, D. M. (2006). The effects of organizational changes on employee commitment: A multilevel investigation. Personnel Psychology, 59, 1–29.

Ford, J. D., Ford, L. W., & D’Amelio, A. (2008). Resistance to change: The rest of the story. Academy of Management Review, 33, 362–377.

Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., & Prussia, G. E. (2008). Employee coping with organizational change: An examination of alternative theoretical perspectives and models. Personnel Psychology, 61, 1–36.

Get ready. United States Small Business Association. Retrieved November 21, 2008, from http://www.sba.gov/smallbusinessplanner/plan/getready/SERV_SBPLANNER_ISENTFORU.html.

Herold, D. M., Fedor, D. B., & Caldwell, S. (2007). Beyond change management: A multilevel investigation of contextual and personal influences on employees’ commitment to change. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 942–951.

Huy, Q. N. (1999). Emotional capability, emotional intelligence, and radical change. Academy of Management Review, 24, 325–345.

Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Pucik, V., & Welbourne, T. M. (1999). Managerial coping with organizational change. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 107–122.

Labianca, G., Gray, B., & Brass D. J. (2000). A grounded model of organizational schema change during empowerment. Organization Science, 11, 235–257.

Lasica, J. D. (2005). Darknet: Hollywood’s war against the digital generation. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Lerman, R. I., & Schmidt, S. R. (2006). Trends and challenges for work in the 21st century. Retrieved September 10, 2008, from U.S. Department of Labor Web site, http://www.dol.gov/oasam/programs/history/herman/reports/futurework/conference/trends/trendsI.htm.

Rafferty, A. E., & Griffin. M. A. (2006). Perceptions of organizational change: A stress and coping perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1154–1162.

Wanberg, C. R., & Banas, J. T. (2000). Predictors and outcomes of openness to changes in a reorganizing workplace. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 132–142.

McGoon, C. (March 1995). Secrets of building influence. Communication World, 12(3), 16.

Michelman, P. (July 2007). Overcoming resistance to change. Harvard Management Update, 12(7), 3–4.

Stanley, T. L. (January 2002). Change: A common-sense approach. Supervision, 63(1), 7–10.