6

Essential Questions:

- What are the elements of the stress response?

- What are common stressors in the modern workplace?

- What are individual strategies one can use to manage their stress response

- What are organizational strategies being incorporated to deal with worker stress?

Facing Foreclosue

The Case of Camden Property Trust

For the third year in a row, Camden Property Trust (NYSE: CPT) has been named one of Fortune magazine’s “100 Best Companies to Work For.” In 2010, the company went from 41 on the list to number 10. Established in 1982 and headquartered in Houston, Texas, Camden Property owns and develops multifamily residential apartment buildings. With 183 properties and 63,286 apartment homes, the real estate giant focuses its development on the fastest-growing markets in the United States. But like so many organizations in the real estate industry during the 2007 and 2008 subprime mortgage crises, business took a turn for the worst, and the company was faced with a substantial slowdown.

Camden realized that cuts would be inevitable and in 2009 announced that it would be reducing the number of planned development projects, which meant a 3% reduction of overall employees and a 50% cut of development staff. Camden’s organizational culture and motto is to “have fun.” Because the company understood the importance of honesty and open communication with its staff, a strong sense of mutual respect had been developed and cultivated well before the crisis, and as a result the company was able to maintain the trust of its employees during the difficult time.

Downsizing and layoffs are two of the most prevalent forms of stress at the workplace and if not handled properly can create severe psychological strain. Part of Camden’s success during the transition was the company’s ability to give staff the necessary information about the situation. Reinforcing the culture of fun at a past annual conference, the then CEO of Camden dressed as Captain Kirk from Star Trek and referred to the tough economic times as “attacks” on the company, and then he laid out a plan of action to bring about victory. Camden has found a way to successfully relate its organizational culture through various modes of communication.

The value and respect that Camden Property shows to its employees has carried over to the way it treats its customers. The company has discovered that doing the right thing makes good business sense. With the increase in foreclosures and unemployment, Camden is marketing to individuals in tough financial situations, a segment of the population once thought of as undesirable tenets. “We’ll forgive a foreclosure, as long as they didn’t totally blow up their credit,” says Camden CEO Richard Campo. The company has also created layoff-proof leases, which grant extensions to people and allow them extra time to come up with the rent. If a resident loses his or her job, the company will let them out of their lease without penalty or try to get them into a less expensive unit. Camden’s ability to build trust with both its employees and its customers during a period of extreme emotional stress ensures that the company will have a committed organization moving forward.1

Discussion Questions

- What do you think the long-term benefits will be for Camden Property Trust and its employees as a result of the way it handled this economic downturn?

- What other suggestions do you have for Camden in creating business opportunities during a period of economic volatility?

- How does a company as large as Camden effectively and authentically communicate to its employees?

- Does Camden increase or decrease its credibility to staff when the CEO dresses up as Captain Kirk?

- What steps has Camden taken to help employees manage their stress levels?

What Is Stress?

Gravity. Mass. Magnetism. These words come from the physical sciences. And so does the term stress. In its original form, the word stress relates to the amount of force applied to a given area. A steel bar stacked with bricks is being stressed in ways that can be measured using mathematical formulas. In human terms, psychiatrist Peter Panzarino notes, “Stress is simply a fact of nature—forces from the outside world affecting the individual.”2 The professional, personal, and environmental pressures of modern life exert their forces on us every day. Some of these pressures are good. Others can wear us down over time. Stress is defined by psychologists as the body’s reaction to a change that requires a physical, mental, or emotional adjustment or response.3 Stress is an inevitable feature of life. It is the force that gets us out of bed in the morning, motivates us at the gym, and inspires us to work.

As you will see in the sections below, stress is a given factor in our lives. We may not be able to avoid stress completely, but we can change how we respond to stress, which is a major benefit. Our ability to recognize, manage, and maximize our response to stress can turn an emotional or physical problem into a resource.

Researchers use polling to measure the effects of stress at work. The results have been eye-opening. According to a 2001 Gallup poll, 80% of American workers report that they feel workplace stress at least some of the time.4 Another survey found that 65% of workers reported job stress as an issue for them, and almost as many employees ended the day exhibiting physical effects of stress, including neck pain, aching muscles, and insomnia. It is clear that many individuals are stressed at work.

The Stress Process

Our basic human functions, breathing, blinking, heartbeat, digestion, and other unconscious actions, are controlled by our lower brains. Just outside this portion of the brain is the semiconscious limbic system, which plays a large part in human emotions. Within this system is an area known as the amygdala. The amygdala is responsible for, among other things, stimulating fear responses. Unfortunately, the amygdala cannot distinguish between meeting a 10:00 a.m. marketing deadline and escaping a burning building.

Human brains respond to outside threats to our safety with a message to our bodies to engage in a “fight-or-flight” response.5 Our bodies prepare for these scenarios with an increased heart rate, shallow breathing, and wide-eyed focus. Even digestion and other functions are stopped in preparation for the fight-or-flight response. While these traits allowed our ancestors to flee the scene of their impending doom or engage in a physical battle for survival, most crises at work are not as dramatic as this.

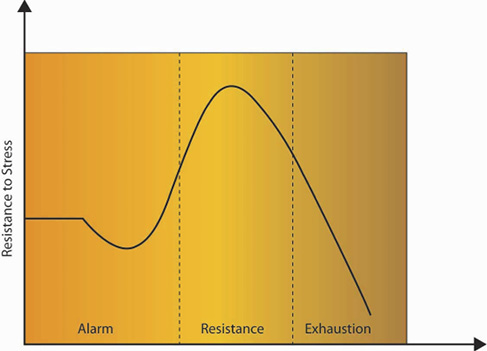

Hans Selye, one of the founders of the American Institute of Stress, spent his life examining the human body’s response to stress. As an endocrinologist who studied the effects of adrenaline and other hormones on the body, Selye believed that unmanaged stress could create physical diseases such as ulcers and high blood pressure, and psychological illnesses such as depression. He hypothesized that stress played a general role in disease by exhausting the body’s immune system and termed this the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) (Figure 1).6

In the alarm phase of stress, an outside stressor jolts the individual, insisting that something must be done. It may help to think of this as the fight-or-flight moment in the individual’s experience. If the response is sufficient, the body will return to its resting state after having successfully dealt with the source of stress.

In the resistance phase, the body begins to release cortisol and draws on reserves of fats and sugars to find a way to adjust to the demands of stress. This reaction works well for short periods of time, but it is only a temporary fix. Individuals forced to endure the stress of cold and hunger may find a way to adjust to lower temperatures and less food. While it is possible for the body to “adapt” to such stresses, the situation cannot continue. The body is drawing on its reserves, like a hospital using backup generators after a power failure. It can continue to function by shutting down unnecessary items like large overhead lights, elevators, televisions, and most computers, but it cannot proceed in that state forever.

In the exhaustion phase, the body has depleted its stores of sugars and fats, and the prolonged release of cortisol has caused the stressor to significantly weaken the individual. Disease results from the body’s weakened state, leading to death in the most extreme cases. This eventual depletion is why we’re more likely to reach for foods rich in fat or sugar, caffeine, or other quick fixes that give us energy when we are stressed. Selye referred to stress that led to disease as distress and stress that was enjoyable or healing as eustress.

Workplace Stressors

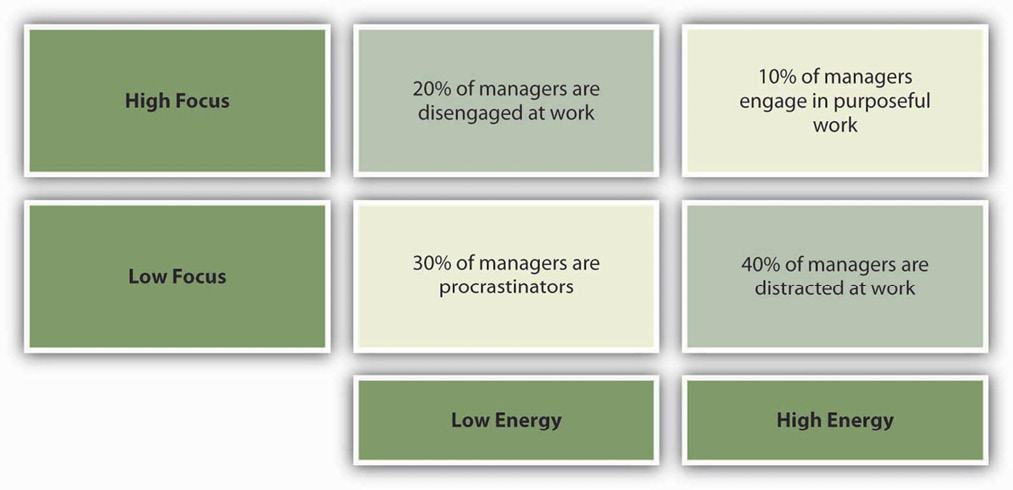

Stressors are events or contexts that cause a stress reaction by elevating levels of adrenaline and forcing a physical or mental response. The key to remember about stressors is that they aren’t necessarily a bad thing. The saying “the straw that broke the camel’s back” applies to stressors. Having a few stressors in our lives may not be a problem, but because stress is cumulative, having many stressors day after day can cause a buildup that becomes a problem. The American Psychological Association surveys American adults about their stresses annually. Topping the list of stressful issues are money, work, and housing.7 But in essence, we could say that all three issues come back to the workplace. How much we earn determines the kind of housing we can afford, and when job security is questionable, home life is generally affected as well. Understanding what can potentially cause stress can help avoid negative consequences. Now we will examine the major stressors in the workplace. A major category of workplace stressors are role demands. In other words, some jobs and some work contexts are more potentially stressful than others (Figure 2).

Role Demands

Role ambiguity refers to vagueness in relation to what our responsibilities are. If you have started a new job and felt unclear about what you were expected to do, you have experienced role ambiguity. Having high role ambiguity is related to higher emotional exhaustion, more thoughts of leaving an organization, and lowered job attitudes and performance.8 Role conflict refers to facing contradictory demands at work. For example, your manager may want you to increase customer satisfaction and cut costs, while you feel that satisfying customers inevitably increases costs. In this case, you are experiencing role conflict because satisfying one demand makes it unlikely to satisfy the other. Role overload is defined as having insufficient time and resources to complete a job. When an organization downsizes, the remaining employees will have to complete the tasks that were previously performed by the laid-off workers, which often leads to role overload. Like role ambiguity, both role conflict and role overload have been shown to hurt performance and lower job attitudes; however, research shows that role ambiguity is the strongest predictor of poor performance.9 Research on new employees also shows that role ambiguity is a key aspect of their adjustment, and that when role ambiguity is high, new employees struggle to fit into the new organization.10

Information Overload

Messages reach us in countless ways every day. Some are societal—advertisements that we may hear or see in the course of our day. Others are professional—e-mails, memos, voice mails, and conversations from our colleagues. Others are personal—messages and conversations from our loved ones and friends. Add these together and it’s easy to see how we may be receiving more information than we can take in. This state of imbalance is known as information overload, which can be defined as “occurring when the information processing demands on an individual’s time to perform interactions and internal calculations exceed the supply or capacity of time available for such processing.”11 Role overload has been made much more salient because of the ease at which we can get abundant information from Web search engines and the numerous e-mail and text messages we receive each day.12 Other research shows that working in such a fragmented fashion significantly impacts efficiency, creativity, and mental acuity.13

The following list includes the Top 10 Most Stressful jobs. As you can see, some of these jobs are stressful due to high emotional labor (customer service), physical demands (miner), time pressures (journalist), or all three (police officer).

- Inner city high school teacher

- Police officer

- Miner

- Air traffic controller

- Medical intern

- Stockbroker

- Journalist

- Customer service or complaint worker

- Secretary

- Waiter

Source: Tolison, B. (2008, April 7). Top ten most stressful jobs. Health. Retrieved January 28, 2009, from the WCTV News Web site: http://www.wctv.tv/news/headlines/17373899.html.

Work–Family Conflict

Work–family conflict occurs when the demands from work and family are negatively affecting one another.14 Specifically, work and family demands on a person may be incompatible with each other such that work interferes with family life and family demands interfere with work life. This stressor has steadily increased in prevalence, as work has become more demanding and technology has allowed employees to work from home and be connected to the job around the clock. In fact, a recent census showed that 28% of the American workforce works more than 40 hours per week, creating an unavoidable spillover from work to family life.15 Moreover, the fact that more households have dual-earning families in which both adults work means household and childcare duties are no longer the sole responsibility of a stay-at-home parent. This trend only compounds stress from the workplace by leading to the spillover of family responsibilities (such as a sick child or elderly parent) to work life. Research shows that individuals who have stress in one area of their life tend to have greater stress in other parts of their lives, which can create a situation of escalating stressors.16 Work–family conflict has been shown to be related to lower job and life satisfaction. Interestingly, it seems that work–family conflict is slightly more problematic for women than men.17 Organizations that are able to help their employees achieve greater work–life balance are seen as more attractive than those that do not.18 Organizations can help employees maintain work–life balance by using organizational practices such as flexibility in scheduling as well as individual practices such as having supervisors who are supportive and considerate of employees’ family life.19

Life Changes

Stress can result from positive and negative life changes. The Holmes-Rahe scale ascribes different stress values to life events ranging from the death of one’s spouse to receiving a ticket for a minor traffic violation. The values are based on incidences of illness and death in the 12 months after each event. On the Holmes-Rahe scale, the death of a spouse receives a stress rating of 100, getting married is seen as a midway stressful event, with a rating of 50, and losing one’s job is rated as 47. These numbers are relative values that allow us to understand the impact of different life events on our stress levels and their ability to impact our health and well-being.20 Again, because stressors are cumulative, higher scores on the stress inventory mean you are more prone to suffering negative consequences of stress than someone with a lower score.

OB Toolbox: How Stressed Are You?

Read each of the events listed in Table 6.1. Give yourself the number of points next to any event that has occurred in your life in the last 2 years. There are no right or wrong answers. The aim is just to identify which of these events you have experienced.

- If you scored fewer than 150 stress points, you have a 30% chance of developing a stress-related illness in the near future.

- If you scored between 150 and 299 stress points, you have a 50% chance of developing a stress-related illness in the near future.

- If you scored over 300 stress points, you have an 80% chance of developing a stress-related illness in the near future.

The happy events in this list such as getting married or an outstanding personal achievement illustrate how eustress, or “good stress,” can also tax a body as much as the stressors that constitute the traditionally negative category of distress. (The prefix eu- in the word eustress means “good” or “well,” much like the eu- in euphoria.) Stressors can also occur in trends. For example, during 2007, nearly 1.3 million U.S. housing properties were subject to foreclosure activity, up 79% from 2006.

Source: Adapted from Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale.Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11, 213–218.

|

Life event |

Stress points |

Life event |

Stress points |

|

Death of spouse |

100 |

Foreclosure of mortgage or loan |

30 |

|

Divorce |

73 |

Change in responsibilities at work |

29 |

|

Marital separation |

65 |

Son or daughter leaving home |

29 |

|

Jail term |

63 |

Trouble with in-laws |

29 |

|

Death of close family member |

63 |

Outstanding personal achievement |

28 |

|

Personal injury or illness |

53 |

Begin or end school |

26 |

|

Marriage |

50 |

Change in living location/condition |

25 |

|

Fired or laid off at work |

47 |

Trouble with supervisor |

23 |

|

Marital reconciliation |

45 |

Change in work hours or conditions |

20 |

|

Retirement |

45 |

Change in schools |

20 |

|

Pregnancy |

40 |

Change in social activities |

18 |

|

Change in financial state |

38 |

Change in eating habits |

15 |

|

Death of close friend |

37 |

Vacation |

13 |

|

Change to different line of work |

36 |

Minor violations of the law |

11 |

Table 6.1 Sample Items: Life Events Stress Inventory

Downsizing

A study commissioned by the U.S. Department of Labor to examine over 3,600 companies from 1980 to 1994 found that manufacturing firms accounted for the greatest incidence of major downsizings. The average percentage of firms by industry that downsized more than 5% of their workforces across the 15-year period of the study was manufacturing (25%), retail (17%), and service (15%). A total of 59% of the companies studied fired at least 5% of their employees at least once during the 15-year period, and 33% of the companies downsized more than 15% of their workforce at least once during the period. Furthermore, during the recessions in 1985 to 1986 and 1990 to 1991, more than 25% of all firms, regardless of size, cut their workforce by more than 5%.21 In the United States, major layoffs in many sectors in 2008 and 2009 were stressful even for those who retained their jobs.

The loss of a job can be a particularly stressful event, as you can see by its high score on the life stressors scale. It can also lead to other stressful events, such as financial problems, which can add to a person’s stress score. Research shows that downsizing and job insecurity (worrying about downsizing) is related to greater stress, alcohol use, and lower performance and creativity.22 For example, a study of over 1,200 Finnish workers found that past downsizing or expectations of future downsizing was related to greater psychological strain and absence.23 In another study of creativity and downsizing, researchers found that creativity and most creativity-supporting aspects of the perceived work environment declined significantly during the downsizing.24 Those who experience layoffs but have their self-integrity affirmed through other means are less susceptible to negative outcomes.25

Outcomes of Stress

The outcomes of stress are categorized into physiological, psychological, and work outcomes.

Stress manifests itself internally as nervousness, tension, headaches, anger, irritability, and fatigue. Stress can also have outward manifestations. Dr. Dean Ornish, author of Stress, Diet and Your Heart, says that stress is related to aging.26 Chronic stress causes the body to secrete hormones such as cortisol, which tend to make our complexion blemished and cause wrinkles. Harvard psychologist Ted Grossbart, author of Skin Deep, says, “Tens of millions of Americans suffer from skin diseases that flare up only when they’re upset.”27 These skin problems include itching, profuse sweating, warts, hives, acne, and psoriasis. For example, Roger Smith, the former CEO of General Motors Corporation, was featured in a Fortune article that began, “His normally ruddy face is covered with a red rash, a painless but disfiguring problem which Smith says his doctor attributes 99% to stress.”28 The human body responds to outside calls to action by pumping more blood through our system, breathing in a more shallow fashion, and gazing wide-eyed at the world. To accomplish this feat, our bodies shut down our immune systems. From a biological point of view, it’s a smart strategic move—but only in the short term. The idea can be seen as your body wanting to escape an imminent threat, so that there is still some kind of body around to get sick later. But in the long term, a body under constant stress can suppress its immune system too much, leading to health problems such as high blood pressure, ulcers, and being overly susceptible to illnesses such as the common cold.

The link between heart attacks and stress, while easy to assume, has been harder to prove. The American Heart Association notes that research has yet to link the two conclusively. Regardless, it is clear that individuals under stress engage in behaviors that can lead to heart disease such as eating fatty foods, smoking, or failing to exercise.

Depression and anxiety are two psychological outcomes of unchecked stress, which are as dangerous to our mental health and welfare as heart disease, high blood pressure, and strokes. The Harris poll found that 11% of respondents said their stress was accompanied by a sense of depression. “Persistent or chronic stress has the potential to put vulnerable individuals at a substantially increased risk of depression, anxiety, and many other emotional difficulties,” notes Mayo Clinic psychiatrist Daniel Hall-Flavin. Scientists have noted that changes in brain function—especially in the areas of the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland—may play a key role in stress-induced emotional problems.29

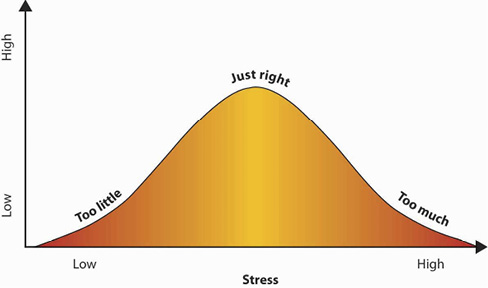

Stress is related to worse job attitudes, higher turnover, and decreases in job performance in terms of both in-role performance and organizational citizenship behaviors.30 Research also shows that stressed individuals have lower organizational commitment than those who are less stressed.31 Interestingly, job challenge has been found to be related to higher performance, perhaps with some individuals rising to the challenge.32 The key is to keep challenges in the optimal zone for stress—the activation stage—and to avoid the exhaustion stage (see Figure 3).33

Absenteeism

Absenteeism refers to unscheduled absences from work. Absenteeism is costly to companies because of its unpredictable nature. When an employee has an unscheduled absence from work, companies struggle to find replacement workers at the last minute. This may involve hiring contingent workers, having other employees work overtime, or scrambling to cover for an absent coworker. The cost of absenteeism to organizations is estimated at $74 billion. According to a Mercer LLC human resource consulting study, 15% of the money spent on payroll is related to absenteeism.34 What causes absenteeism? First we need to look at the type of absenteeism. Some absenteeism is unavoidable and is related to health reasons. For example, reasons such as lower back pain, migraines, accidents on or off the job, or acute stress are important reasons for absenteeism.35 Health-related absenteeism is costly, but dealing with such absenteeism by using organizational policies penalizing absenteeism is both unreasonable and unfair. A sick employee who shows up at work will infect coworkers and will not be productive. Instead, companies are finding that programs aimed at keeping workers healthy are effective in dealing with this type of absenteeism. Companies using wellness programs that educate employees about proper nutrition, help them exercise, and reward them for healthy habits are related to reduced absenteeism.36

Work–life balance is another common reason for absences. Staying home to care for a sick child or relative, attending the wedding of a friend or relative, or skipping work to study for an exam are all common reasons for unscheduled absences. Companies may deal with these by giving employees more flexibility in work hours. If employees can manage their own time, they are less likely to be absent. Organizations such as Lahey Clinic Foundation Inc. at Burlington, Massachusetts, find that instead of separating sick leave and paid time off, merging them is effective in dealing with unscheduled absences. When a company has “sick leave” but no other leave for social and family obligations, employees may fake being sick and use their “sick leave.” Instead, having a single paid time off policy would allow workers to balance work and life, and allow companies to avoid unscheduled absences. Some companies such as IBM Corporation got rid of sick leave altogether and instead allow employees to take as much time as they need, as long as their work gets done.37 Sometimes, absenteeism is a form of work withdrawal and can lead to resignation from the job. In other words, poor work attitudes lead to absenteeism. When employees are dissatisfied with their work or have low organizational commitment, they are likely to be absent more often. In other words, absenteeism is caused by the desire to avoid an unpleasant work environment in addition to related factors such as problems in job design, lack of organizational justice, extreme levels of stress, and ineffective relations with coworkers and supervisors. In this case, management may deal with absenteeism by investigating the causes of dissatisfaction and dealing with them.38 Are there personal factors contributing to absenteeism? Research does not reveal a consistent link between personality and absenteeism. One demographic criterion that predicts absenteeism is age. Interestingly, and counter to the stereotype that increased age would bring more health problems, research shows that age is negatively related to both frequency and duration of absenteeism. Because of reasons including higher loyalty to their company and a stronger work ethic, older employees are less likely be absent from work.39

OB Toolbox: Dealing with Late Coworkers

Do you have team members that are chronically late to group meetings? Are your coworkers driving you crazy because they are perpetually late? Here are some suggestions that may help.

- Try to get to the root cause and find out what is making your coworker unhappy. Often, lateness is an extension of dissatisfaction one feels toward the job or tasks at hand. If there are ways in which you can solve these issues, such as by giving the person more responsibility or listening to the opinions of the person and showing more respect, you can minimize lateness.

- Make sure that lateness does not go without any negative consequences. Do not ignore it, and do not remain silent. Mention carefully and constructively that one person’s lateness slows down everyone.

- Make an effort to schedule meetings around everyone’s schedules. When scheduling, emphasize the importance of everyone’s being there on time and pick a time when everyone can comfortably attend.

- When people are late, be sure to ask them to compensate, such as by doing extra work. Negative consequences tend to discourage future lateness.

- Shortly before the meeting starts, send everyone a reminder. Yes, you are dealing with adults and they should keep their own schedules, but some people’s schedules may be busier than others, and some are better at keeping track of their time. Reminders may ensure that they arrive on time.

- Reward timeliness. When everyone shows up on time, verbally recognize the effort everyone made to be there on time.

- Be on time yourself! Creating a culture of timeliness within your group requires everyone’s effort, including yours.

Sources: Adapted from information in DeLonzor, D. (2005, November). Running late. HR Magazine, 50(11), 109–112; Grainge, Z. (2006, November 21). Spotlight on…lateness. Personnel Today, p. 33.

Turnover

Turnover refers to an employee leaving an organization. Employee turnover has potentially harmful consequences, such as poor customer service and poor companywide performance. When employees leave, their jobs still need to be performed by someone, so companies spend time recruiting, hiring, and training new employees, all the while suffering from lower productivity. Yet, not all turnover is bad. Turnover is particularly a problem when high-performing employees leave, while a poor performer’s turnover may actually give the company a chance to improve productivity and morale.

Why do employees leave? An employee’s performance level is an important reason. People who perform poorly are actually more likely to leave. These people may be fired or be encouraged to quit, or they may quit because of their fear of being fired. If a company has pay-for-performance systems, poor performers will find that they are not earning much, owing to their substandard performance. This pay discrepancy gives poor performers an extra incentive to leave. On the other hand, instituting a pay-for-performance system does not mean that high performers will always stay with a company. Note that high performers may find it easier to find alternative jobs, so when they are unhappy, they can afford to quit their jobs voluntarily.40

Work attitudes are often the primary culprit in why people leave. When workers are unhappy at work, and when they are not attached to their companies, they are more likely to leave. Loving the things they do, being happy with the opportunities for advancement within the company, and being happy about pay are all aspects of work attitudes relating to turnover. Of course, the link between work attitudes and turnover is not direct. When employees are unhappy, they might have the intention to leave and may start looking for a job, but their ability to actually leave will depend on many factors such as their employability and the condition of the job market. For this reason, when national and regional unemployment is high, many people who are unhappy will still continue to work for their current company. When the economy is doing well, people will start moving to other companies in response to being unhappy. Many companies make an effort to keep employees happy because of an understanding of the connection between employee happiness and turnover. As illustrated in the opening case, at the SAS Institute, employees enjoy amenities such as a swimming pool, child care at work, and a 35-hour workweek. The company’s turnover is around 4%–5%. This percentage is a stark contrast to the industry average, which is in the range of 12%–20%.41

People are more likely to quit their jobs if they experience stress at work as well. Stressors such as role conflict and role ambiguity drain energy and motivate people to seek alternatives. For example, call-center employees experience a great deal of stress in the form of poor treatment from customers, long work hours, and constant monitoring of their every action. Companies such as EchoStar Corporation realize that one method for effectively retaining their best employees is to give employees opportunities to move to higher responsibility jobs elsewhere in the company. When a stressful job is a step toward a more desirable job, employees seem to stick around longer.42

There are also individual differences in whether people leave or stay. For example, personality is a factor in the decision to quit one’s job. People who are conscientious, agreeable, and emotionally stable are less likely to quit their jobs. Many explanations are possible. People with these personality traits may perform better at work, which leads to lower quit rates. Additionally, they may have better relations with coworkers and managers, which is a factor in their retention. Whatever the reason, it seems that some people are likely to stay longer at any given job regardless of the circumstances.43

Whether we leave a job or stay also depends on our age and how long we have been there. It seems that younger employees are more likely to leave. This is not surprising, because people who are younger will have fewer responsibilities such as supporting a household or dependents. As a result, they can quit a job they don’t like much more easily. Similarly, people who have been with a company for a short period of time may quit more easily. New employees experience a lot of stress at work, and there is usually not much keeping them in the company, such as established bonds to a manager or colleagues. New employees may even have ongoing job interviews with other companies when they start working; therefore, they may leave more easily. For example, Sprint Nextel Corporation found that many of their new hires were quitting within 45 days of their hiring dates. When they investigated, they found that newly hired employees were experiencing a lot of stress from avoidable problems such as unclear job descriptions or problems hooking up their computers. Sprint was able to solve the turnover problem by paying special attention to orienting new hires.44

OB Toolbox: Tips for Leaving Your Job Gracefully

Few people work in one company forever, and someday you may decide that your current job is no longer right for you. Here are tips on how to leave without burning any bridges.

- Don’t quit on an impulse. We all have bad days and feel the temptation to walk away from the job right away. Yet, this is unproductive for your own career. Plan your exit in advance, look for a better job over an extended period of time, and leave when the moment is right.

- Don’t quit too often. While trading jobs in an upward fashion is good, leaving one place and getting another job that is just like the previous one in pay, responsibilities, and position does not help you move forward in your career, and makes you look like a quitter. Companies are often wary of hiring job hoppers.

- When you decide to leave, tell your boss first, and be nice. Don’t discuss all the things your manager may have done wrong. Explain your reasons without blaming anyone and frame it as an issue of poor job fit.

- Do not badmouth your employer. It is best not to bash the organization you are leaving in front of coworkers. Do not tell them how happy you are to be quitting or how much better your new job looks. There is really no point in making any remaining employees feel bad.

- Guard your professional reputation. You must realize that the world is a small place. People know others and tales of unprofessional behavior travel quickly to unlikely places.

- Finish your ongoing work and don’t leave your team in a bad spot. Right before a major deadline is probably a bad time to quit. Offer to stay at least 2 weeks to finish your work, and to help hire and train your replacement.

- Don’t steal from the company! Give back all office supplies, keys, ID cards, and other materials. Don’t give them any reason to blemish their memory of you. Who knows…you may even want to come back one day.

Sources: Adapted from information in Challenger, J. E. (1992, November–December), How to leave your job without burning bridges. Women in Business, 44(6), 29; Daniels, C., & Vinzant, C. (2000, February 7). The joy of quitting, Fortune, 141(3), 199–202; Schroeder, J. (2005, November). Leaving your job without burning bridges. Public Relations Tactics, 12(11), 4; Woolnough, R. (2003, May 27). The right and wrong ways to leave your job. Computer Weekly, 55.

Individual Differences in Experienced Stress

How we handle stress varies by individual, and part of that issue has to do with our personality type. Type A personalities, as defined by the Jenkins Activity Survey display high levels of speed/impatience, job involvement, and hard-driving competitiveness.45 If you think back to Selye’s General Adaptation Syndrome, in which unchecked stress can lead to illness over time, it’s easy to see how the fast-paced, adrenaline-pumping lifestyle of a Type A person can lead to increased stress, and research supports this view.46 Studies show that the hostility and hyper-reactive portion of the Type A personality is a major concern in terms of stress and negative organizational outcomes.47 Type B personalities, by contrast, are calmer by nature. They think through situations as opposed to reacting emotionally. Their fight-or-flight and stress levels are lower as a result. Our personalities are the outcome of our life experiences and, to some degree, our genetics. Some researchers believe that mothers who experience a great deal of stress during pregnancy introduce their unborn babies to high levels of the stress-related hormone cortisol in utero, predisposing their babies to a stressful life from birth.48 Men and women also handle stress differently. Researchers at Yale University discovered estrogen may heighten women’s response to stress and their tendency to depression as a result.49 Still, others believe that women’s stronger social networks allow them to process stress more effectively than men.50 So while women may become depressed more often than men, women may also have better tools for countering emotion-related stress than their male counterparts.

OB Toolbox: To Cry or Not to Cry? That Is the Questi

As we all know, stress can build up. Advice that’s often given is to “let it all out” with something like a cathartic “good cry.” But research shows that crying may not be as helpful as the adage would lead us to believe. In reviewing scientific studies done on crying and health, Ad Vingerhoets and Jan Scheirs found that the studies “yielded little evidence in support of the hypothesis that shedding tears improves mood or health directly, be it in the short or in the long run.” Another study found that venting actually increased the negative effects of negative emotion.51 Instead, laughter may be the better remedy. Crying may actually intensify the negative feelings, because crying is a social signal not only to others but to yourself. “You might think, ‘I didn’t think it was bothering me that much, but look at how I’m crying—I must really be upset,’” says Susan Labott of the University of Toledo. The crying may make the feelings more intense. Labott and Randall Martin of Northern Illinois University at Dekalb surveyed 715 men and women and found that at comparable stress levels, criers were more depressed, anxious, hostile, and tired than those who wept less. Those who used humor were the most successful at combating stress. So, if you’re looking for a cathartic release, opt for humor instead: Try to find something funny in your stressful predicament.

Sources: Vingerhoets, A. J. J. M., & Scheirs, J. G. M. (2001). Crying and health. In A. J. J. M. Vingerhoets & R. R. Cornelius (Eds.), Adult crying: A biopsychosocial approach (pp. 227–247). East Sussex, UK: Brunner-Routledge; Martin, R., & Susan L. (1991). Mood following emotional crying: Effects of the situation. Journal of Research in Personality, 25(2), 218–233; Bostad, R. The crying game. Anchor Point, 1–8. Retrieved June 19, 2008, from http://www.nlpanchorpoint.com/BolstadCrying1481.pdf

Key Takeaway

Stress is prevalent in today’s workplaces. The General Adaptation Syndrome consists of alarm, resistance, and eventually exhaustion if the stress goes on for too long. Time pressure is a major stressor. Outcomes of stress include both psychological and physiological problems as well as work outcomes. Individuals with Type B personalities are less prone to stress. In addition, individuals with social support experience less stress.

Exercises

- We’ve just seen how the three phases of the General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS) can play out in terms of physical stresses such as cold and hunger. Can you imagine how the three categories of this model might apply to work stress as well?

- List two situations in which a prolonged work challenge might cause an individual to reach the second and third stage of GAS.

- What can individuals do to help manage their time better? What works for you?

- What symptoms of stress have you seen in yourself or your peers?

Avoiding and Managing Stress: Individual Approaches to Managing Stress

Luckily, there are several ways to manage stress, including improved performance, work flow, diet, exercise, sleep social support, and time management.

One way is to harness stress’s ability to improve our performance. Jack Groppel was working as a professor of kinesiology and bioengineering at the University of Illinois when he became interested in applying the principles of athletic performance to workplace performance. Could eating better, exercising more, and developing a positive attitude turn distress into eustress? Groppel’s answer was yes. If professionals trained their minds and bodies to perform at peak levels through better nutrition, focused training, and positive action, Groppel said, they could become “corporate athletes” working at optimal physical, emotional, and mental levels.

The “corporate athlete” approach to stress is a proactive (action first) rather than a reactive (response-driven) approach. While an overdose of stress can cause some individuals to stop exercising, eat less nutritional foods, and develop a sense of hopelessness, corporate athletes ward off the potentially overwhelming feelings of stress by developing strong bodies and minds that embrace challenges, as opposed to being overwhelmed by them.

Work Flow

Turning stress into fuel for corporate athleticism is one way of transforming a potential enemy into a workplace ally. Another way to transform stress is by breaking challenges into smaller parts, and embracing the ones that give us joy. In doing so, we can enter a state much like that of a child at play, fully focused on the task at hand, losing track of everything except our genuine connection to the challenge before us. This concept of total engagement in one’s work, or in other activities, is called flow. The term flow was coined by psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and is defined as a state of consciousness in which a person is totally absorbed in an activity. We’ve all experienced flow: It’s the state of mind in which you feel strong, alert, and in effortless control.

According to this way of thinking, the most pleasurable way for a person to work is in harmony with his or her true interests. Work is seen as more similar to playing games than most activities adults do. This is because work consists of tasks, puzzles, surprises, and potentially rewarding challenges. By breaking down a busy workday into smaller pieces, individuals can shift from the “stress” of work to a more engaged state of flow.

Keep in mind that work that flows includes the following:

- Challenge: the task is reachable but requires a stretch

- Meaningfulness: the task is worthwhile or important

- Competence: the task uses skills that you have

- Choice: you have some say in the task and how it’s carried out

Source: Csikszentmihalyi, C. (1997).Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. New York: Basic Books.

Corporate athleticism and flow are two concepts that can help you cope with stress. Next, let us focus more on exactly how individual lifestyle choices affect our stress levels. Eating well, exercising, getting enough sleep, and employing time management techniques are all things we can affect that can decrease our feelings of stress.

Diet

Greasy foods often make a person feel tired. Why? Because it takes the body longer to digest fats, which means the body is diverting blood from the brain and making you feel sluggish. Eating big, heavy meals in the middle of the day may actually slow us down, because the body will be pumping blood to the stomach, away from the brain. A better choice for lunch might be fish, such as wild salmon. Fish keeps you alert because of its effect on two important brain chemicals—dopamine and norepinephrine—which produce a feeling of alertness, increased concentration, and faster reaction times.52

Exercise

Exercise is another strategy for managing stress. The best kind of break to take may be a physically active one. Research has shown that physically active breaks lead to enhanced mental concentration and decreased mental fatigue. One study, conducted by Belgian researchers, examined the effect of breaks on workers in a large manufacturing company. One-half of the workers were told to rest during their breaks. The other half did mild calisthenics. Afterward, each group was given a battery of tests. The group who had done the mild calisthenics scored far better on all measures of memory, decision-making ability, eye–hand coordination, and fine motor control.53

Strange as it may seem, exercise gives us more energy. How energetic we feel depends on our maximum oxygen capacity (the total amount of oxygen we utilize from the air we breathe). The more oxygen we absorb in each breath, the more energy and stamina we will have. Yoga and meditation are other physical activities that are helpful in managing stress. Regular exercise increases our body’s ability to draw more oxygen out of the air we breathe. Therefore, taking physically active breaks may be helpful in combating stress.

Sleep

It is a vicious cycle. Stress can make it hard to sleep. Not sleeping makes it harder to focus on work in general, as well as on specific tasks. Tired folks are more likely to lose their temper, upping the stress level of others. American insomnia is a stress-related epidemic—one-third of adults claim to have trouble sleeping and 37% admit to actually having fallen asleep while driving in the past year.54

The work–life crunch experienced by many Americans makes a good night’s sleep seem out of reach. According to the journal Sleep, workers who suffer from insomnia are more likely to miss work due to exhaustion. These missed days ultimately cost employers thousands of dollars per person in missed productivity each year, which can total over $100 billion across all industries. For additional resources, go to the National Sleep Foundation Web site: http://www.nationalsleepfoundation.org. As you might imagine, a person who misses work due to exhaustion will return to work to find an even more stressful workload. This cycle can easily increase the stress level of a work team as well as the overtired individual.

Create a Social Support Network

A consistent finding is that those individuals who have a strong social support network are less stressed than those who do not.55 Research finds that social support can buffer the effects of stress.56 Individuals can help build up social support by encouraging a team atmosphere in which coworkers support one another. Just being able to talk with and listen to others, either with coworkers at work or with friends and family at home, can help decrease stress levels.

Time Management

Time management is defined as the development of tools or techniques that help to make us more productive when we work. Effective time management is a major factor in reducing stress, because it decreases much of the pressure we feel. With information and role overload it is easy to fall into bad habits of simply reacting to unexpected situations. Time management techniques include prioritizing, manageable organization, and keeping a schedule such as a paper or electronic organizing tool. Just like any new skill, developing time management takes conscious effort, but the gains might be worthwhile if your stress level is reduced.

Organizational Approaches to Managing Stress

Stress-related issues cost businesses billions of dollars per year in absenteeism, accidents, and lost productivity.57 As a result, managing employee stress is an important concern for organizations as well as individuals. For example, Renault, the French automaker, invites consultants to train their 2,100 supervisors to avoid the outcomes of negative stress for themselves and their subordinates. IBM Corporation encourages its worldwide employees to take an online stress assessment that helps them create action plans based on their results. Even organizations such as General Electric Company (GE) that are known for a “winner takes all” mentality are seeing the need to reduce stress. Lately, GE has brought in comedians to lighten up the workplace atmosphere, and those receiving low performance ratings are no longer called the “bottom 10s” but are now referred to as the “less effectives.”58 Organizations can take many steps to helping employees with stress, including having more clear expectations of them, creating jobs where employees have autonomy and control, and creating a fair work environment. Finally, larger organizations normally utilize outside resources to help employees get professional help when needed.

Make Expectations Clear

One way to reduce stress is to state your expectations clearly. Workers who have clear descriptions of their jobs experience less stress than those whose jobs are ill defined.59 The same thing goes for individual tasks. Can you imagine the benefits of working in a place where every assignment was clear and employees were content and focused on their work? It would be a great place to work as a manager, too. Stress can be contagious, but as we’ve seen above, this kind of happiness can be contagious, too. Creating clear expectations doesn’t have to be a top–down event. Managers may be unaware that their directives are increasing their subordinates’ stress by upping their confusion. In this case, a gentle conversation that steers a project in a clearer direction can be a simple but powerful way to reduce stress. In the interest of reducing stress on all sides, it’s important to frame situations as opportunities for solutions as opposed to sources of anger.

Give Employees Autonomy

Giving employees a sense of autonomy is another thing that organizations can do to help relieve stress.60 It has long been known that one of the most stressful things that individuals deal with is a lack of control over their environment. Research shows that individuals who feel a greater sense of control at work deal with stress more effectively both in the United States and in Hong Kong.61 Similarly, in a study of American and French employees, researchers found that the negative effects of emotional labor were much less for those employees with the autonomy to customize their work environment and customer service encounters.62 Employees’ stress levels are likely to be related to the degree that organizations can build autonomy and support into jobs.

Create Fair Work Environments

Work environments that are unfair and unpredictable have been labeled “toxic workplaces.” A toxic workplace is one in which a company does not value its employees or treat them fairly.63 Statistically, organizations that value employees are more profitable than those that do not.64 Research shows that working in an environment that is seen as fair helps to buffer the effects of stress.65 This reduced stress may be because employees feel a greater sense of status and self-esteem or due to a greater sense of trust within the organization. These findings hold for outcomes individuals receive as well as the process for distributing those outcomes.66 Whatever the case, it is clear that organizations have many reasons to create work environments characterized by fairness, including lower stress levels for employees. In fact, one study showed that training supervisors to be more interpersonally sensitive even helped nurses feel less stressed about a pay cut.67

Supervisor Support: Work-Family Conflict Survey

Think of your current or most recent supervisor and rate each of the following items in terms of this person’s behavior toward you.

Answer the following questions using 1 = not at all, 2 = somewhat, 3 = fully agree

|

1. |

_____ |

My supervisor is willing to listen to my problems in juggling work and nonwork life. |

|

2. |

_____ |

My supervisor takes the time to learn about my personal needs. |

|

3. |

_____ |

My supervisor makes me feel comfortable talking to him or her about my conflicts between work and nonwork. |

|

4. |

_____ |

My supervisor and I can talk effectively to solve conflicts between work and nonwork issues. |

|

5. |

_____ |

I can depend on my supervisor to help me with scheduling conflicts if I need it. |

|

6. |

_____ |

I can rely on my supervisor to make sure my work responsibilities are handled when I have unanticipated nonwork demands. |

|

7. |

_____ |

My supervisor works effectively with workers to creatively solve conflicts between work and nonwork. |

|

8. |

_____ |

My supervisor is a good role model for work and nonwork balance. |

|

9. |

_____ |

My supervisor demonstrates effective behaviors in how to juggle work and nonwork balance. |

|

10. |

_____ |

My supervisor demonstrates how a person can jointly be successful on and off the job. |

|

11. |

_____ |

My supervisor thinks about how the work in my department can be organized to jointly benefit employees and the company. |

|

12. |

_____ |

My supervisor asks for suggestions to make it easier for employees to balance work and nonwork demands. |

|

13. |

_____ |

My supervisor is creative in reallocating job duties to help my department work better as a team. |

|

14. |

_____ |

My supervisor is able to manage the department as a whole team to enable everyone’s needs to be met. |

Add up all your ratings to see how your supervisor stacks up.

Score total = _______________

Scoring:

- A score of 14 to 23 indicates low levels of supervisor support.

- A score of 24 to 33 indicates average levels of supervisor support.

- A score of 34 to 42 indicates high levels of supervisor support.

Adapted from Hammer, L. B., Kossek, E. E., Yragui, N. L., Bodner, T. E., & Hanson, G. C. (in press). Development and validation of a multidimensional measure of family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB). Journal of Management. DOI: 10.1177/0149206308328510. Used by permission of Sage Publications.

Telecommuting

Telecommuting refers to working remotely. For example, some employees work from home, a remote satellite office, or from a coffee shop for some portion of the workweek. Being able to work away from the office is one option that can decrease stress for some employees. Of course, while an estimated 45 million individuals telecommute each year, telecommuting is not for everyone.68 At Merrill Lynch & Co. Inc., those who are interested in telecommuting are put through a rigorous training program that includes 2 weeks in one of their three home office simulation labs in Florida, New Jersey, or Manhattan to see if telecommuting is a good fit for the employee. Employees must also submit photos of their home office and a work plan. AT&T Inc. estimates that nearly 55% of its U.S.-based managers telecommute at some point in the week, and this method is also popular with managers around the world.69 A recent survey found that 43% of government workers now telecommute at least part time. This trend has been growing in reaction to a law passed by the U.S. Congress in 2000 requiring federal agencies to offer working from home as an option.70 Merrill Lynch has seen higher productivity, less stress, lower turnover, and higher job satisfaction for those who telecommute.71 A recent meta-analysis of all the studies of telecommuting (12,883 employees) confirmed researcher findings that the higher autonomy of working from home resulted in lower work–family conflict for these employees. Even more encouraging were the findings of higher job satisfaction, better performance, and lower stress as well.72 Of course, telecommuting can also cause potential stress. The keys to successful telecommuting arrangements are to match the right employees with the right jobs to the right environments. If any variable is not within a reasonable range, such as having a dog that barks all day when the employee is at home, productivity will suffer.

Employee Sabbaticals

Sabbaticals (paid time off from the normal routine at work) have long been a sacred ritual practiced by universities to help faculty stay current, work on large research projects, and recharge every 5 to 8 years. However, many companies such as Genentech Inc., Container Store Inc., and eBay Inc. are now in the practice of granting paid sabbaticals to their employees. While 11% of large companies offer paid sabbaticals and 29% offer unpaid sabbaticals, 16% of small companies and 21% of medium-sized companies do the same.73 For example, at PricewaterhouseCoopers International Ltd., you can apply for a sabbatical after just 2 years on the job if you agree to stay with the company for at least 1 year following your break. Time off ranges from 3 to 6 months and entails either a personal growth plan or one for social services where you help others.74

Employee Assistance Programs

There are times when life outside work causes stress in ways that will impact our lives at work and beyond. These situations may include the death of a loved one, serious illness, drug and alcohol dependencies, depression, or legal or financial problems that are impinging on our work lives. Although treating such stressors is beyond the scope of an organization or a manager, many companies offer their employees outside sources of emotional counseling. Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) are often offered to workers as an adjunct to a company-provided health care plan. Small companies in particular use outside employee assistance programs, because they don’t have the needed expertise in-house. As their name implies, EAPs offer help in dealing with crises in the workplace and beyond. EAPs are often used to help workers who have substance abuse problems.

Key Takeaway

There are many individual and organizational approaches to decreasing stress and avoiding negative outcomes. Individuals can control their diet, exercise, and sleep routines; build a social support network; and practice better time management. Organizations can help make expectations clear, give employees autonomy, create fair work environments, consider telecommuting, give employee sabbaticals, and utilize employee assistance programs.

Exercises

- Have you ever been in a state of “flow” as described in this section? If so, what was special about this time?

- Whose responsibility do you think it is to deal with employee stress—the employee or the organization? Why?

- Do you think most organizations are fair or unfair? Explain your answer.

- Have you ever considered telecommuting? What do you think would be the pros and cons for you personally?

References

1. Marino, V. (2008, March 23). A bright spot for housing investors? New York Times. Retrieved April 22, 2010, from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/23/realestate/23sqft.html?fta=y; Palmeri, C. (2009, March 16). Courting the foreclosed. BusinessWeek, p. 12; Thrash, R. (2009, December 11). Leasing agents use idea from car sales for renters. St. Petersburg Times, p. 3; Jones, B. (2009, December 28). REITs look to get back on track. Real Estate Finance and Investment; Caccamese, L. (2008). Managing under stress: How the Best Companies to Work For address staff reductions. Great Place to Work Institute. Retrieved February 21, 2009, from http://resources.greatplacetowork.com/article/pdf/managing-staff -reductions.pdf.

2. Panzarino, P. (2008, February 15). Stress. Retrieved from Medicinenet.com. Retrieved May 21, 2008, from http://www.medicinenet.com/stress/article.htm.

3. Dyer, K. A. (2006). Definition of stress. Retrieved May 21, 2008, from About.com: http://dying.about.com/od/glossary/g/stress_distress.htm.

4. Kersten, D. (2002, November 12). Get a grip on job stress. USA Today. Retrieved May 21, 2008, from http://www.usatoday.com/money/jobcenter/workplace/stress management/2002-11-12-job-stress_x.htm.

5. Cannon, W. (1915). Bodily changes in pain, hunger, fear and rage: An account of recent researches into the function of emotional excitement. New York: D. Appleton.

6. Selye, H. (1946). The general adaptation syndrome and the diseases of adaptation. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology, 6, 117; Selye, H. (1976).Stress of life (Rev. ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

7. American Psychological Association. (2007, October 24). Stress a major health problem in the U.S., warns APA. Retrieved May 21, 2008, from the American Psychological Association Web site: http://www.apa.org/releases/stressproblem.html.

8. Fisher, C. D., & Gittelson, R. (1983). A meta-analysis of the correlates of role conflict and role ambiguity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 68, 320–333; Jackson, S. E., & Shuler, R. S. (1985). A meta-analysis and conceptual critique of research on role ambiguity and role conflict in work settings. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 36, 16–78; Örtqvist, D., & Wincent, J. (2006). Prominent consequences of role stress: A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Stress Management, 13, 399–422.

9. Gilboa, S., Shirom, A., Fried, Y., & Cooper, C. (2008). A meta-analysis of work demand stressors and job performance: Examining main and moderating effects. Personnel Psychology, 61, 227–271; Tubre, T. C., & Collins, J. M. (2000). Jackson and Schuler (1985) Revisited: A meta-analysis of the relationships between role ambiguity, role conflict, and performance.Journal of Management, 26, 155–169.

10. Bauer, T. N., Bodner, T., Erdogan, B., Truxillo, D. M., & Tucker, J. S. (2007). Newcomer adjustment during organizational socialization: A meta-analytic review of antecedents, outcomes, and methods. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 707–721.

11. Schick, A. G., Gordon, L. A., & Haka, S. (1990). Information overload: A temporal approach. Accounting, organizations, and society, 15, 199–220.

12. Definition of information overload available at PCMag.com. Retrieved May 21, 2008, from http://www.pcmag.com/encyclopedia_term/0,2542,t=information+overload &i=44950,00.asp; Additional information can be found in Dawley, D. D., & Anthony, W. P. (2003). User perceptions of e-mail at work. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 17, 170–200.

13. Based on Overholt, A. (2001, February). Intel’s got (too much) mail. Fast Company. Retrieved May 22, 2008, from http://www.fastcompany.com/online/44/intel.html and http://blogs.intel.com/it/2006/10/information_overload.php.

14. Netemeyer, R. G., Boles, J. S., & McMurrian, R. (1996). Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 400–410.

15. U.S. Census Bureau. (2004). Labor Day 2004. Retrieved May 22, 2008, from the U.S. Census Bureau Web site: http://www.census.gov/press-release/www/releases/archives/facts_for_features_special_editions/002264.html.

16. Allen, T. D., Herst, D. E. L., Bruck, C. S., & Sutton, M. (2000). Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 278–308; Ford, M. T., Heinen, B. A., & Langkamer, K. L. (2007). Work and family satisfaction and conflict: A meta-analysis of cross-domain relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 57–80; Frone, M. R., Russell, R., & Cooper, M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work–family conflict: Testing a model of the work–family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 65–78; Hammer, L. B., Bauer, T. N., & Grandey, A. A. (2003). Work–family conflict and work–related withdrawal behaviors. Journal of Business & Psychology, 17, 419–436.

17. Kossek, E. E., & Ozeki, C. (1998). Work–family conflict, policies, and the job–life satisfaction relationship: A review and directions for organizational behavior–human resources research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 139–149.

18. Barnett, R. C., & Hall, D. T. (2001). How to use reduced hours to win the war for talent. Organizational Dynamics, 29, 192–210; Greenhaus, J. H., & Powell, G. (2006). When work and family are allies: A theory of work–family enrichment. Academy of Management Review, 31, 72–92.

19. Thomas, L. T., & Ganster, D. C. (1995). Impact of family-supportive work variables on work–family conflict and strain: A control perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 6–15.

20. Fontana, D. (1989). Managing stress. Published by the British Psychology Society and Routledge.

21. Slocum, J. W., Morris, J. R., Cascio, W. F., & Young, C. E. (1999). Downsizing after all these years: Questions and answers about who did it, how many did it, and who benefited from it. Organizational Dynamics, 27, 78–88.

22. Moore, S., Grunberg, L., & Greenberg, E. (2004). Repeated downsizing contact: The effects of similar and dissimilar layoff experiences on work and well-being outcomes. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 9, 247–257; Probst, T. M., Stewart, S. M., Gruys, M. L., & Tierney, B. W. (2007). Productivity, counterproductivity and creativity: The ups and downs of job insecurity. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 80, 479–497; Sikora, P., Moore, S., Greenberg, E., & Grunberg, L. (2008). Downsizing and alcohol use: A cross-lagged longitudinal examination of the spillover hypothesis. Work & Stress, 22, 51–68.

23. Kalimo, R., Taris, T. W., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2003). The effects of past and anticipated future downsizing on survivor well-being: An Equity perspective. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 8, 91–109.

24. Amabile, T. M., & Conti, R. (1999). Changes in the work environment for creativity during downsizing. Academy of Management Journal, 42, 630–640.

25. Wiesenfeld, B. M., Brockner, J., Petzall, B., Wolf, R., & Bailey, J. (2001). Stress and coping among layoff survivors: A self-affirmation analysis. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal, 14, 15–34.

26. Ornish, D. (1984). Stress, diet and your heart. New York: Signet.

27. Grossbart, T. (1992). Skin deep. New Mexico: Health Press.

28. Taylor, A. (1987, August 3). The biggest bosses. Fortune. Retrieved May 23, 2008, from http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/1987/08/03/69388/index.htm.

29. Mayo Clinic Staff. (2008, February 26). Chronic stress: Can it cause depression? Retrieved May 23, 2008, from the Mayo Clinic Web site: http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/stress/AN01286.

30. Mayo Clinic Staff. (2008, February 26). Chronic stress: Can it cause depression? Retrieved May 23, 2008, from the Mayo Clinic Web site: http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/stress/AN01286; Gilboa, S., Shiron, A., Fried, Y., & Cooper, C. (2008). A meta-analysis of work demand stressors and job performance: Examining main and moderating effects. Personnel Psychology, 61, 227–271; Podsakoff, N. P., LePine, J. A., & LePine, M. A. (2007). Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 438–454.

31. Cropanzano, R., Rupp, D. E., & Byrne, Z. S. (2003). The relationship of emotional exhaustion to work attitudes, job performance, and organizational citizenship behaviors.Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 160–169.

32. Podsakoff, N. P., LePine, J. A., & LePine, M. A. (2007). Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 438–454.

33. Quick, J. C., Quick, J. D., Nelson, D. L., & Hurrell, J. J. (1997). Preventative stress management in organizations. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

34. Conlin, M. (2007, November 12). Shirking working: The war on hooky. Business Week,4058, 72–75; Gale, S. F. (2003). Sickened by the cost of absenteeism, companies look for solutions. Workforce Management, 82(9), 72–75.

35. Farrell, D., & Stamm, C. L. (1988). Meta-analysis of the correlates of employee absence. Human Relations, 41, 211–227; Martocchio, J. J., Harrison, D. A., & Berkson, H. (2000). Connections between lower back pain, interventions, and absence from work: A time-based meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 53, 595–624.

36. Parks, K. M., & Steelman, L. A. (2008). Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 13, 58–68.

37. Cole, C. L. (2002). Sick of absenteeism? Get rid of sick days. Workforce, 81(9), 56–61; Conlin, M. (2007, November 12). Shirking working: The war on hooky. Business Week, 4058, 72–75; Baltes, B. B., Briggs, T. E., Huff, J. W., Wright, J. A., & Neuman, G. A. (1999). Flexible and compressed workweek schedules: A meta-analysis of their effects on work-related criteria. Journal of Applied Psychology,84, 496–513.

38. Farrell, D., & Stamm, C. L. (1988). Meta-analysis of the correlates of employee absence. Human Relations, 41, 211–227; Hackett, R. D. (1989). Work attitudes and employee absenteeism: A synthesis of the literature.Journal of Occupational Psychology, 62, 235–248; Scott, K. D., & Taylor, G. S. (1985). An examination of conflicting findings on the relationship between job satisfaction and absenteeism: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 28, 599–612.

39. Martocchio, J. J. (1989). Age-related differences in employee absenteeism: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 4, 409–414; Ng, T. W. H., & Feldman, D. C. (2008). The relationship of age to ten dimensions of job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 392–423.

40. Williams, C. R., & Livingstone, L. P. (1994). Another look at the relationship between performance and voluntary turnover. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 269–298.

41. Carsten, J. M., & Spector, P. E. (1987). Unemployment, job satisfaction, and employee turnover: A meta-analytic test of the Muchinsky model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72, 374–381; Cohen, A. (1991). Career stage as a moderator of the relationships between organizational commitment and its outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 64, 253–268; Cohen, A. (1993). Organizational commitment and turnover: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 1140–1157; Cohen, A., & Hudecek, N. (1993). Organizational commitment—turnover relationship across occupational groups: A meta-analysis. Group & Organization Management, 18, 188–213; Griffeth, R. W., Hom, P. W., & Gaertner, S. (2000). A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management, 26, 463–488; Hom, P. W., Caranikas-Walker, F., Prussia, G. E., & Griffeth, R. W. (1992). A meta-analytical structural equations analysis of a model of employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 890–909; Karlgaard, R. (2006). Who wants to be public? Forbes Asia, 2(17), 22; Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscivitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61, 20–52; Steel, R. P., & Ovalle, N. K. (1984). A review and meta-analysis of research on the relationship between behavioral intentions and employee turnover. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69, 673–686; Tett, R. P., & Meyer, J. P. (1993). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intentions, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Personnel Psychology, 46, 259–293.

42. Badal, J. (2006, July 24). “Career path” programs help retain workers. Wall Street Journal, p. B1; Griffeth, R. W., Hom, P. W., & Gaertner, S. (2000). A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management, 26, 463–488; Podsakoff, N. P., LePine, J. A., & LePine, M. A. (2007). Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 438–454.

43. Salgado, J. F. (2002). The Big Five personality dimensions and counterproductive behaviors. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 10, 117–125; Zimmerman, R. D. (2008). Understanding the impact of personality traits on individuals’ turnover decisions: A meta-analytic path model. Personnel Psychology, 61, 309–348.

44. Cohen, A. (1991). Career stage as a moderator of the relationships between organizational commitment and its outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 64, 253–268; Cohen, A. (1993). Organizational commitment and turnover: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 1140–1157; Ebeling, A. (2007). Corporate moneyball. Forbes, 179(9), 102–103.

45. Jenkins, C. D., Zyzanski, S., & Rosenman, R. (1979). Jenkins activity survey manual. New York: Psychological Corporation.

46. Spector, P. E., & O’Connell, B. J. (1994). The contribution of personality traits, negative affectivity, locus of control and Type A to the subsequent reports of job stressors and job strains. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 67, 1–11.

47. Ganster, D. C. (1986). Type A behavior and occupational stress. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 8, 61–84.

48. BBC News. (2007, January 26). Stress “harms brain in the womb.” Retrieved May 23, 2008, from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/6298909.stm.

49. Weaver, J. (2004, January 21). Estrogen makes the brain more vulnerable to stress. Yale University Medical News. Retrieved May 23, 2008, from http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2004-01/yu-emt012104.php.

50. Personality types impact on response to stress. (n.d.). Retrieved June 5, 2008, from the Discovery Health Web site: http://health.discovery.com/centers/stress/articles/pnstress/pnstress.html.

51. Brown, S. P., Westbrook, R. A., & Challagalla, G. (2005). Good cope, bad cope: Adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies following a critical negative work event. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 792–798.

52. Wurtman, J. (1988). Managing your mind and mood through food. New York: Harper Perennial.

53. Miller, P. M. (1986). Hilton head executive stamina program. New York: Rawson Associates.

54. Tumminello, L. (2007, November 5). The National Sleep Foundation’s State of the States Report on Drowsy Driving finds fatigued driving to be under-recognized and underreported. Retrieved May 23, 2008, from the National Sleep Foundation Web site: http://www.drowsydriving.org/site/c.lqLPIROCKtF/b.3568679/.

55. Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2006). Sources of social support and burnout: A meta-analytic test of the conservation of resources model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1134–1145.

56. Van Yperfen, N. W., & Hagedoorn, M. (2003). Do high job demands increase intrinsic motivation or fatigue or both? The role of job control and job social support. Academy of Management Journal, 46, 339–348.

57. Hobson, C., Kesic, D., Rosetti, D., Delunas, L., & Hobson, N. (2004, September). Motivating employee commitment with empathy and support during stressful life events.International Journal of Management Web site. Retrieved January 21, 2008 from http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa5440/is_200409/ai_n21362646?tag=content;col1.

58. Dispatches from the war on stress: Business begins to reckon with the enormous costs of workplace angst. (2007, August 6).Business Week. Retrieved May 23, 2008, from http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/07_32/b4045061.htm? campaign_id=rss_null.

59. Jackson, S. E., & Schuler, R. S. (1985). A meta-analysis and conceptual critique of research on role ambiguity and role conflict in work settings. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 36, 16–78; Sauter S. L., Murphy L. R., & Hurrell J. J., Jr. (1990). Prevention of work-related psychological disorders.American Psychologist, 45, 1146–1158.

60. Kossek, E. E., Lautschb, B. A., & Eaton, S. C. (2006). Telecommuting, control, and boundary management: Correlates of policy use and practice, job control, and work–family effectiveness.Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68, 347–367.

61. Schaubroeck, J., Lam, S. S. K., & Xie, J. L. (2000). Collective efficacy versus self-efficacy in coping responses to stressors and control: A cross-cultural study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 512–525.

62. Grandey, A. A., Fisk, G. M., & Steiner, D. D. (2005). Must “service with a smile” be stressful? The moderating role of personal control for American and French employees. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 893–904.

63. Webber, A. M. (1998). Danger: Toxic company. Fast Company. Retrieved June 1, 2008, from http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/19/toxic.html?page=0%2C1.

64. Huselid, M. A. (1995). The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 635–672; Pfeffer, J. (1998). The human equation: Building profits by putting people first. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; Pfeffer, J., & Veiga, J. F. (1999). Putting people first for organizational success. Academy of Management Executive, 13, 37–48; Welbourne, T., & Andrews, A. (1996). Predicting performance of Initial Public Offering firms: Should HRM be in the equation? Academy of Management Journal, 39, 910–911.

65. Judge, T. A., & Colquitt, J. A. (2004). Organizational justice and stress: The mediating role of work-family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 395–404.