5

Essential Questions

- What are the elements of personality that impact us on the job?

- What are the value sets that influence our work attitudes and behavior?

- How does visual perception influence our work attitudes and behavior?

- What are the factors related to job satisfaction and organizational commitment?

- What are common job behaviors and what influences them?

Personality and Values

Personality

Personality encompasses a person’s relatively stable feelings, thoughts, and behavioral patterns. Each of us has a unique personality that differentiates us from other people, and understanding someone’s personality gives us clues about how that person is likely to act and feel in a variety of situations. To manage effectively, it is helpful to understand the personalities of different employees. Having this knowledge is also useful for placing people into jobs and organizations.

If personality is stable, does this mean that it does not change? You probably remember how you have changed and evolved as a result of your own life experiences, parenting style and attention you have received in early childhood, successes and failures you experienced over the course of your life, and other life events. In fact, personality does change over long periods of time. For example, we tend to become more socially dominant, more conscientious (organized and dependable), and more emotionally stable between the ages of 20 and 40, whereas openness to new experiences tends to decline as we age (Roberts, 2006). In other words, even though we treat personality as relatively stable, change occurs. Moreover, even in childhood, our personality matters, and it has lasting consequences for us. For example, studies show that part of our career success and job satisfaction later in life can be explained by our childhood personality (Judge & Higgins, 1999; Staw, et. al., 1986).

Is our behavior in organizations dependent on our personality? To some extent, yes, and to some extent, no. While we will discuss the effects of personality for employee behavior, you must remember that the relationships we describe are modest correlations. For example, having a sociable and outgoing personality may encourage people to seek friends and prefer social situations. This does not mean that their personality will immediately affect their work behavior. At work, we have a job to do and a role to perform. Therefore, our behavior may be more strongly affected by what is expected of us, as opposed to how we want to behave. Especially in jobs that involve a lot of autonomy, or freedom, personality tends to exert a strong influence on work behavior (Barrick & Mount, 1993),something to consider when engaging in Organizing activities such as job design or enrichment.

Big Five Personality Traits

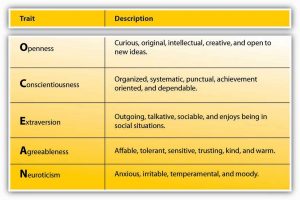

How many personality traits are there? How do we even know? In every language, there are many words describing a person’s personality. In fact, in the English language, more than 15,000 words describing personality have been identified. When researchers analyzed the traits describing personality characteristics, they realized that many different words were actually pointing to a single dimension of personality. When these words were grouped, five dimensions seemed to emerge, and these explain much of the variation in our personalities (Goldberg, 1990). These five are not necessarily the only traits out there. There are other, specific traits that represent other dimensions not captured by the Big Five. Still, understanding them gives us a good start for describing personality (Figure 1).

As you can see, the Big Five dimensions are openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and Neuroticism—if you put the initials together, you get the acronym OCEAN. Everyone has some degree of each of these traits; it is the unique configuration of how high a person rates on some traits and how low on others that produces the individual quality we call personality.

Openness is the degree to which a person is curious, original, intellectual, creative, and open to new ideas. People high in openness seem to thrive in situations that require flexibility and learning new things. They are highly motivated to learn new skills, and they do well in training settings (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Lievens, et. al., 2003). They also have an advantage when they enter into a new organization. Their open-mindedness leads them to seek a lot of information and feedback about how they are doing and to build relationships, which leads to quicker adjustment to the new job (Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). When given support, they tend to be creative (Baer & Oldham, 2006). Open people are highly adaptable to change, and teams that experience unforeseen changes in their tasks do well if they are populated with people high in openness (LePine, 2003). Compared with people low in openness, they are also more likely to start their own business (Zhao & Seibert, 2006). The potential downside is that they may also be prone to becoming more easily bored or impatient with routine.

Conscientiousness refers to the degree to which a person is organized, systematic, punctual, achievement-oriented, and dependable. Conscientiousness is the one personality trait that uniformly predicts how high a person’s performance will be across a variety of occupations and jobs (Barrick & Mount, 1991). In fact, conscientiousness is the trait most desired by recruiters, and highly conscientious applicants tend to succeed in interviews (Dunn, et. al., 1995; Tay, et. al., 2006). Once they are hired, conscientious people not only tend to perform well, but they also have higher levels of motivation to perform, lower levels of turnover, lower levels of absenteeism, and higher levels of safety performance at work (Judge & Ilies, 2002; Judge, et. al., 1997; Wallace & Chen 2006; Zimmerman, 2008). One’s conscientiousness is related to career success and career satisfaction over time (Judge & Higgins, 1999).Finally, it seems that conscientiousness is a valuable trait for entrepreneurs. Highly conscientious people are more likely to start their own business compared with those who are not conscientious, and their firms have longer survival rates (Certo & Certo, 2005; Zhao & Seibert, 2006). A potential downside is that highly conscientious individuals can be detail-oriented rather than seeing the big picture.

Extraversion is the degree to which a person is outgoing, talkative, sociable, and enjoys socializing. One of the established findings is that they tend to be effective in jobs involving sales (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Vinchur, et. al., 1998). Moreover, they tend to be effective as managers and they demonstrate inspirational leadership behaviors (Bauer, et. al., 2006; Bono & Judge, 2004). extraverts do well in social situations, and, as a result, they tend to be effective in job interviews. Part of this success comes from preparation, as they are likely to use their social network to prepare for the interview (Caldwell & Burger, 1998; Tay & Van Dyne, 2006). Extraverts have an easier time than introverts do when adjusting to a new job. They actively seek information and feedback and build effective relationships, which helps them adjust (Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, 2000). Interestingly, extraverts are also found to be happier at work, which may be because of the relationships they build with the people around them and their easier adjustment to a new job (Judge & Mount, 2002). However, they do not necessarily perform well in all jobs; jobs depriving them of social interaction may be a poor fit. Moreover, they are not necessarily model employees. For example, they tend to have higher levels of absenteeism at work, potentially because they may miss work to hang out with or attend to the needs of their friends (Judge, et. al., 1997) (Figure 2).

Agreeableness is the degree to which a person is affable, tolerant, sensitive, trusting, kind, and warm. In other words, people who are high in agreeableness are likeable people who get along with others. Not surprisingly, agreeable people help others at work consistently; this helping behavior does not depend on their good mood (Ilies, et. al., 2006). They are also less likely to retaliate when other people treat them unfairly (Skarlicki, et. al., 1999). This may reflect their ability to show empathy and to give people the benefit of the doubt. Agreeable people may be a valuable addition to their teams and may be effective leaders because they create a fair environment when they are in leadership positions (Mayer, et. al., 2007). At the other end of the spectrum, people low in agreeableness are less likely to show these positive behaviors. Moreover, people who are disagreeable are shown to quit their jobs unexpectedly, perhaps in response to a conflict with a boss or a peer (Zimmerman, 2008). If agreeable people are so nice, does this mean that we should only look for agreeable people when hiring? You might expect some jobs to require a low level of agreeableness. Think about it: When hiring a lawyer, would you prefer a kind and gentle person or someone who can stand up to an opponent? People high in agreeableness are also less likely to engage in constructive and change-oriented communication (LePine & Van Dyne, 2001). Disagreeing with the status quo may create conflict, and agreeable people may avoid creating such conflict, missing an opportunity for constructive change.

Neuroticism refers to the degree to which a person is anxious, irritable, temperamental, and moody. It is perhaps the only Big Five dimension where scoring high is undesirable. Neurotic people have a tendency to have emotional adjustment problems and habitually experience stress and depression. People very high in Neuroticism experience a number of problems at work. For example, they have trouble forming and maintaining relationships and are less likely to be someone people go to for advice and friendship (Klein, et. al., 2004). They tend to be habitually unhappy in their jobs and report high intentions to leave, but they do not necessarily actually leave their jobs (Judge, et. al., 2002; Zimmerman, 2008)) Being high in Neuroticism seems to be harmful to one’s career, as these employees have lower levels of career success (measured with income and occupational status achieved in one’s career). Finally, if they achieve managerial jobs, they tend to create an unfair climate at work (Mayer, et. al., 2007).

In contrast, people who are low on Neuroticism—those who have a positive affective disposition—tend to experience positive moods more often than negative moods. They tend to be more satisfied with their jobs and more committed to their companies (Connolly & Viswesvaran, 2000; Throresen, et. al., 2003). This is not surprising, as people who habitually see the glass as half full will notice the good things in their work environment while those with the opposite character will find more things to complain about. Whether these people are more successful in finding jobs and companies that will make them happy, build better relationships at work that increase their satisfaction and commitment, or simply see their environment as more positive, it seems that low Neuroticism is a strong advantage in the workplace.

Other Personality Dimensions

In addition to the Big Five, researchers have proposed various other dimensions, or traits, of personality. These include self-monitoring, proactive personality, self-esteem, and self-efficacy.

Self-monitoring refers to the extent to which a person is capable of monitoring his or her actions and appearance in social situations. People who are social monitors are social chameleons who understand what the situation demands and act accordingly, while low social monitors tend to act the way they feel (Snyder, 1974; Snyder, 1987). High social monitors are sensitive to the types of behaviors the social environment expects from them. Their ability to modify their behavior according to the demands of the situation they are in and to manage their impressions effectively are great advantages for them (Turnley & Bolino, 2001). They are rated as higher performers and emerge as leaders (Day, et. al., 2002). They are effective in influencing other people and are able to get things done by managing their impressions. As managers, however, they tend to have lower accuracy in evaluating the performance of their employees. It seems that while trying to manage their impressions, they may avoid giving accurate feedback to their subordinates to avoid confrontations, which could hinder a manager’s ability to carry out the Controlling function (Jawahar, 2001).

Proactive personality refers to a person’s inclination to fix what is wrong, change things, and use initiative to solve problems. Instead of waiting to be told what to do, proactive people take action to initiate meaningful change and remove the obstacles they face along the way. Proactive individuals tend to be more successful in their job searches (Brown, et. al., 2006). They also are more successful over the course of their careers because they use initiative and acquire greater understanding of how the politics within the company work (Seibert, 1999; Seibert, et. al., 2001). Proactive people are valuable assets to their companies because they may have higher levels of performance (Crant, 1995). They adjust to their new jobs quickly because they understand the political environment better and make friends more quickly (Kammeyer-Mueller & Wanberg, 2003; Thompson, 2005). Proactive people are eager to learn and engage in many developmental activities to improve their skills (Major, et. al., 2006). For all their potential, under some circumstances proactive personality may be a liability for a person or an organization. Imagine a person who is proactive but is perceived as too pushy, trying to change things other people are not willing to let go of, or using their initiative to make decisions that do not serve a company’s best interests. Research shows that a proactive person’s success depends on his or her understanding of the company’s core values, ability, and skills to perform the job and ability to assess situational demands correctly (Chan, 2006; Erdogan & Bauer, 2005).

Self-esteem is the degree to which a person has overall positive feelings about himself or herself. People with high self-esteem view themselves in a positive light, are confident, and respect themselves. In contrast, people with low self-esteem experience high levels of self-doubt and question their self-worth. High self-esteem is related to higher levels of satisfaction with one’s job and higher levels of performance on the job (Judge & Bono, 2001). People with low self-esteem are attracted to situations where they will be relatively invisible, such as large companies (Turban & Keon, 1993). Managing employees with low self-esteem may be challenging at times because negative feedback given with the intention of improving performance may be viewed as a negative judgment on their worth as an employee. Therefore, effectively managing employees with relatively low self-esteem requires tact and providing lots of positive feedback when discussing performance incidents.

Self-Esteem Around the Globe

Which nations have the highest average self-esteem? Researchers asked this question by surveying almost 17,000 individuals across 53 nations, in 28 languages.

On the basis of this survey, these are the top 10 nations in terms of self-reported self-esteem:

- Serbia

- Chile

- Israel

- Peru

- Estonia

- United States of America

- Turkey

- Mexico

- Croatia

- Austria

The following are the 10 nations with the lowest self-reported self-esteem:

- South Korea

- Switzerland

- Morocco

- Slovakia

- Fiji

- Taiwan

- Czech Republic

- Bangladesh

- Hong Kong

- Japan

Source: Adapted from information in Denissen, J. J. A., Penke, L., & Schmitt, D. P. (2008, July). Self-esteem reactions to social interactions: Evidence for sociometer mechanisms across days, people, and nations. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 95, 181–196; Hitti, M. (2005). Who’s No. 1 in self-esteem? Serbia is tops, Japan ranks lowest, U.S. is no. 6 in global survey. WebMD. Retrieved November 14, 2008, from http://www.webmd.com/skin-beauty/news/20050927/whos-number-1-in-self-esteem; Schmitt, D. P., & Allik, J. (2005). The simultaneous administration of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale in 53 nationals: Culture-specific features of global self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 623–642.

Self-efficacy is a belief that one can perform a specific task successfully. Research shows that the belief that we can do something is a good predictor of whether we can actually do it. Self-efficacy is different from other personality traits in that it is job specific. You may have high self-efficacy in being successful academically, but low self-efficacy in relation to your ability to fix your car. At the same time, people have a certain level of generalized self-efficacy, and they have the belief that whatever task or hobby they tackle, they are likely to be successful in it.

Research shows that self-efficacy at work is related to job performance (Bauer, et. al., 2007; Judge, et. al., 2007; Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). This is probably because people with high self-efficacy actually set higher goals for themselves and are more committed to their goals, whereas people with low self-efficacy tend to procrastinate (Phillips & Gully, 1997; Steel, 2007; Wofford, et. al., 1992). Academic self-efficacy is a good predictor of your grade point average, as well as whether you persist in your studies or drop out of college (Robbins, et. al., 2004).

Is there a way of increasing employee’s self-efficacy? In addition to hiring people who are capable of performing the required job tasks, training people to increase their self-efficacy may be effective. Some people may also respond well to verbal encouragement. By showing that you believe they can be successful and effectively playing the role of cheerleader, a manager may be able to increase self-efficacy beliefs. Empowering people—giving them opportunities to test their skills so that they can see what they are capable of—is also a good way of increasing self-efficacy (Ahearne, et. al., 2005).

Personality Testing in Employee Selection

Personality is a potentially important predictor of work behavior. In job interviews, companies try to assess a candidate’s personality and the potential for a good match, but interviews are only as good as the people conducting them. In fact, interviewers are not particularly good at detecting the best trait that predicts performance: conscientiousness (Barrick, et. al., 2000) (see Figure 3).

One method some companies use to improve this match and detect the people who are potentially good job candidates is personality testing. Several companies conduct pre-employment personality tests. Companies using them believe that these tests improve the effectiveness of their selection and reduce turnover. For example, Overnight Transportation in Atlanta found that using such tests reduced their on-the-job delinquency by 50%–100% (Emmett, 2004; Gale, 2002).

Yet, are these methods good ways of employee selection? Experts have not yet reached an agreement on this subject and the topic is highly controversial. Some experts cite data indicating that personality tests predict performance and other important criteria such as job satisfaction. However, we must understand that how a personality test is used influences its validity. Imagine filling out a personality test in class. You will probably fill it out as honestly as you can. Then, if your instructor correlates your personality scores with your class performance, we could say that the correlation is meaningful. But now imagine that your instructor tells you, before giving you the test, that based on your test scores, you will secure a coveted graduate assistant position, which comes with a tuition waiver and a stipend. In that case, would you still fill out the test honestly or would you try to make your personality look as “good” as possible?

In employee selection, where the employees with the “best” personalities will be the ones receiving a job offer, a complicating factor is that people filling out the survey do not have a strong incentive to be honest. In fact, they have a greater incentive to guess what the job requires and answer the questions in a way they think the company is looking for. As a result, the rankings of the candidates who take the test may be affected by their ability to fake. Some experts believe that this is a serious problem (Morgeson, et. al., 2007; Morgeson, et. al., 2007). Others point out that even with faking the tests remain valid—the scores are related to job performance (Barrick & Mount, 1996; Ones, et. al., 2007; Ones, et. al., 1996; Tett & Christansen, 2007). It is even possible that the ability to fake is related to a personality trait that increases success at work, such as social monitoring.

Scores on personality self-assessments are distorted for other reasons beyond the fact that some candidates can fake better than others. Do we even know our own personalities? Are we the best person to ask this question? How supervisors, coworkers, and customers see our personality may matter more than how we see ourselves. Therefore, using self-report measures of performance may not be the best way of measuring someone’s personality (Mount, et. al., 1994). We have our blind areas. We may also give “aspirational” answers. If you are asked whether you are honest, you may think “yes, I always have the intention to be honest.” This actually says nothing about your actual level of honesty.

Another problem with using these tests is the uncertain relationship between performance and personality. On the basis of research, personality is not a particularly strong indicator of how a person will perform. According to one estimate, personality only explains about 10%–15% of variation in job performance. Our performance at work depends on many factors, and personality does not seem to be the key factor for performance. In fact, cognitive ability (your overall mental intelligence) is a more powerful predictor of job performance. Instead of personality tests, cognitive ability tests may do a better job of predicting who will be good performers. Personality is a better predictor of job satisfaction and other attitudes, but screening people out on the assumption that they may be unhappy at work is a challenging argument to make in an employee selection context.

In any case, if an organization decides to use these tests for selection, it is important to be aware of their limitations. If they are used together with other tests, such as tests of cognitive abilities, they may contribute to making better decisions. The company should ensure that the test fits the job and actually predicts performance. This is called validating the test. Before giving the test to applicants, the company could give it to existing employees to find out the traits that are most important for success in this particular company and job. Then, in the selection context, the company can pay particular attention to those traits.

Finally, the company also needs to make sure that the test does not discriminate against people on the basis of sex, race, age, disabilities, and other legally protected characteristics. Rent-a-Center experienced legal difficulties when the test they used was found to violate the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). The company used the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory for selection purposes, but this test was developed to diagnose severe mental illnesses; it included items such as “I see things or people around me others do not see.” In effect, the test served the purpose of a clinical evaluation and was discriminating against people with mental illnesses, which is a protected category under ADA (Heller, 2005).

Values

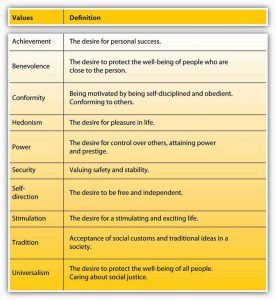

Values refer to people’s stable life goals, reflecting what is most important to them. Values are established throughout one’s life as a result of accumulating life experiences, and values tend to be relatively stable (Lusk & Oliver, 1974; Rokeach, 1973). The values that are important to a person tend to affect the types of decisions they make, how they perceive their environment, and their actual behaviors. Moreover, a person is more likely to accept a job offer when the company possesses the values he or she cares about (Judge & Bretz, 1972; Ravlin & Meglino, 1987). Value attainment is one reason people stay in a company. When a job does not help them attain their values, they are likely to decide to leave if they are dissatisfied with the job (George & Jones, 1996) (Figure 4).

What are the values people care about? As with personality dimensions, researchers have developed several frameworks, or typologies, of values. One of the particularly useful frameworks includes 10 values (Schwartz, 1992).

Values a person holds will affect their employment. For example, someone who values stimulation highly may seek jobs that involve fast action and high risk, such as firefighter, police officer, or emergency medicine. Someone who values achievement highly may be likely to become an entrepreneur or intrapreneur. And an individual who values benevolence and universalism may seek work in the nonprofit sector with a charitable organization or in a “helping profession,” such as nursing or social work. Like personality, values have implications for Organizing activities, such as assigning duties to specific jobs or developing the chain of command; employee values are likely to affect how employees respond to changes in the characteristics of their jobs.

In terms of work behaviors, a person is more likely to accept a job offer when the company possesses the values he or she cares about. A firm’s values are often described in the company’s mission and vision statements, an element of the Planning function (Judge & Bretz, 1992; Ravlin & Meglino, 1987). Value attainment is one reason people stay in a company. When a job does not help them attain their values, they are likely to decide to leave if they are also dissatisfied with the job (George & Jones, 1996).

Key Takeaway

Personality traits and values are two dimensions on which people differ. Personality is the unique, relatively stable pattern of feelings, thoughts, and behavior that each individual displays. Big Five personality dimensions (openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and Neuroticism) are important traits; others that are particularly relevant for work behavior include self-efficacy, self-esteem, social monitoring, and proactive personality. While personality is a stronger influence over job attitudes, its relation to job performance is weaker. Some companies use personality testing to screen out candidates. Companies using personality tests are advised to validate their tests and use them to supplement other techniques with greater validity, such as tests of cognitive ability. Companies must also ensure that a test does not discriminate against any protected group. Values express a person’s life goals; they are similar to personality traits in that they are relatively stable over time. In the workplace, a person is more likely to accept a job that provides opportunities for value attainment. People are also more likely to remain in a job and career that satisfy their values.

Exercises

- Think about the personality traits covered in this section. Can you think of jobs or occupations that seem particularly suited to each trait? Which traits would be universally desirable across all jobs?

- What are the unique challenges of managing employees who have low self-efficacy and self-esteem? How would you deal with this situation?

- What are some methods that companies can use to assess employee personality?

- Have you ever held a job where your personality did not match the demands of the job? How did you react to this situation? How were your attitudes and behaviors affected?

- Identify ways in which the Big Five (of the manager and/or the employees) may affect how you as a manager would carry out the Leadership function.

Perception

Our behavior is not only a function of our personality and values but also of the situation. We interpret our environment, formulate responses, and act accordingly. Perception may be defined as the process by which individuals detect and interpret environmental stimuli. What makes human perception so interesting is that we do not solely respond to the stimuli in our environment. We go beyond the information that is present in our environment, pay selective attention to some aspects of the environment, and ignore other elements that may be immediately apparent to other people.

Our perception of the environment is not entirely rational. For example, have you ever noticed that while glancing at a newspaper or a news Web site, information that is especially interesting or important to you jumps out of the page and catches your eye? If you are a sports fan, while scrolling down the pages, you may immediately see a news item describing the latest success of your team. If you are the mother of a picky eater, an advice column on toddler feeding may be the first thing you see when looking at the page. If you were recently turned down for a loan, an item of financial news may jump out at you. Therefore, what we see in the environment is a function of what we value, our needs, our fears, and our emotions(Higgins & Bargh, 1987; Keltner, et. al., 1993). In fact, what we see in the environment may be objectively flat out wrong because of such mental tendencies. For example, one experiment showed that when people who were afraid of spiders were shown spiders, they inaccurately thought that the spider was moving toward them (Riskind, et. al., 1995).

In this section, we will describe some common perceptual tendencies we engage in when perceiving objects or other people and the consequences of such perceptions. Our coverage of these perceptual biases is not exhaustive—there are many other biases and tendencies that can be found in the way people perceive stimuli.

Visual Perception

Our visual perception definitely goes beyond the physical information available to us; this phenomenon is commonly referred to as “optical illusions.” Artists and designers of everything from apparel to cars to home interiors make use of optical illusions to enhance the look of the product. Managers rely on their visual perception to form their opinions about people and objects around them and to make sense of data presented in graphical form. Therefore, understanding how our visual perception may be biased is important.

First, we extrapolate from the information available to us. Take a look at the first figure (Figure 5). The white triangle you see in the middle is not really there, but we extrapolate from the information available to us and see it there. Similarly, when we look at objects that are partially blocked, we see the whole (Kellman & Shipley, 1991).

How do these tendencies influence behavior in organizations? The fact that our visual perception is faulty means that managers should not always take what they see at face value. Let’s say that you do not like one of your peers and you think that you saw this person surfing the Web during work hours. Are you absolutely sure, or are you simply filling the gaps? Have you really seen this person surf unrelated Web sites, or is it possible that the person was searching for work-related purposes? The tendency to fill in the gaps also causes our memory to be faulty. Imagine that you have been at a meeting where several people made comments that you did not agree with. After the meeting, you may attribute most of these comments to people you did not like. In other words, you may twist the reality to make your memories more consistent with your opinions of people.

The tendency to compare and contrast objects and people to each other also causes problems. For example, if you are a manager who has been given an office much smaller than the other offices on the floor, you may feel that your workspace is crowded and uncomfortable. If the same office is surrounded by smaller offices, you may actually feel that your office is comfortable and roomy. In short, our biased visual perception may lead to the wrong inferences about the people and objects around us (Figure 6).

Self-Perception

Human beings are prone to errors and biases when perceiving themselves. Moreover, the type of bias people have depends on their personality. Many people suffer from self-enhancement bias. This is the tendency to overestimate our performance and capabilities and see ourselves in a more positive light than others see us. People who have a narcissistic personality are particularly subject to this bias, but many others also have this bias to varying degrees (John & Robins, 1994). At the same time, other people have the opposing extreme, which may be labeled as self-effacement bias (or modesty bias). This is the tendency to underestimate our performance and capabilities and to see events in a way that puts ourselves in a more negative light. We may expect that people with low self-esteem may be particularly prone to making this error. These tendencies have real consequences for behavior in organizations. For example, people who suffer from extreme levels of self-enhancement tendencies may not understand why they are not getting promoted or rewarded, while those who have a tendency to self-efface may project low confidence and take more blame for their failures than necessary.

When human beings perceive themselves, they are also subject to the false consensus error. Simply put, we overestimate how similar we are to other people (Fields & Schuman, 1976; Ross, et. al., 1977). We assume that whatever quirks we have are shared by a larger number of people than in reality. People who take office supplies home, tell white lies to their boss or colleagues, or take credit for other people’s work to get ahead may genuinely feel that these behaviors are more common than they really are. The problem for behavior in organizations is that, when people believe that a behavior is common and normal, they may repeat the behavior more freely. Under some circumstances, this may lead to a high level of unethical or even illegal behaviors.

Social Perception

How we perceive other people in our environment is also shaped by our biases. Moreover, how we perceive others will shape our behavior, which in turn will shape the behavior of the person we are interacting with.

One of the factors biasing our perception is stereotypes. Stereotypes are generalizations based on a group characteristic. For example, believing that women are more cooperative than men or that men are more assertive than women are stereotypes. Stereotypes may be positive, negative, or neutral. In the abstract, stereotyping is an adaptive function—we have a natural tendency to categorize the information around us to make sense of our environment. Just imagine how complicated life would be if we continually had to start from scratch to understand each new situation and each new person we encountered! What makes stereotypes potentially discriminatory and a perceptual bias is the tendency to generalize from a group to a particular individual. If the belief that men are more assertive than women leads to choosing a man over an equally qualified female candidate for a position, the decision will be biased, unfair, and potentially illegal.

Stereotypes often create a situation called self-fulfilling prophecy. This happens when an established stereotype causes one to behave in a certain way, which leads the other party to behave in a way that confirms the stereotype (Snyder, et. al., 1977). If you have a stereotype such as “Asians are friendly,” you are more likely to be friendly toward an Asian person. Because you are treating the other person more nicely, the response you get may also be nicer, which confirms your original belief that Asians are friendly. Of course, just the opposite is also true. Suppose you believe that “young employees are slackers.” You are less likely to give a young employee high levels of responsibility or interesting and challenging assignments. The result may be that the young employee reporting to you may become increasingly bored at work and start goofing off, confirming your suspicions that young people are slackers!

Stereotypes persist because of a process called selective perception. Selective perception simply means that we pay selective attention to parts of the environment while ignoring other parts, which is particularly important during the Planning process. Our background, expectations, and beliefs will shape which events we notice and which events we ignore. For example, an executive’s functional background will affect the changes he or she perceives in the environment (Waller, et. al., 1995). Executives with a background in sales and marketing see the changes in the demand for their product, while executives with a background in information technology may more readily perceive the changes in the technology the company is using. Selective perception may also perpetuate stereotypes because we are less likely to notice events that go against our beliefs. A person who believes that men drive better than women may be more likely to notice women driving poorly than men driving poorly. As a result, a stereotype is maintained because information to the contrary may not even reach our brain!

Let’s say we noticed information that goes against our beliefs. What then? Unfortunately, this is no guarantee that we will modify our beliefs and prejudices. First, when we see examples that go against our stereotypes, we tend to come up with subcategories. For example, people who believe that women are more cooperative when they see a female who is assertive may classify her as a “career woman.” Therefore, the example to the contrary does not violate the stereotype and is explained as an exception to the rule (Higgins & Bargh, 1987). Or, we may simply discount the information. In one study, people in favor of and against the death penalty were shown two studies, one showing benefits for the death penalty while the other disconfirming any benefits. People rejected the study that went against their belief as methodologically inferior and ended up believing in their original position even more (Lord, et. al., 1979)! In other words, using data to debunk people’s beliefs or previously established opinions may not necessarily work, a tendency to guard against when conducting Planning and Controlling activities.

One other perceptual tendency that may affect work behavior is first impressions (Figure 7). The first impressions we form about people tend to have a lasting effect. In fact, first impressions, once formed, are surprisingly resilient to contrary information. Even if people are told that the first impressions were caused by inaccurate information, people hold on to them to a certain degree because once we form first impressions, they become independent from the evidence that created them (Ross, et. al., 1975). Therefore, any information we receive to the contrary does not serve the purpose of altering them. Imagine the first day that you met your colleague Anne. She treated you in a rude manner, and when you asked for her help, she brushed you off. You may form the belief that Anne is a rude and unhelpful person. Later on, you may hear that Anne’s mother is seriously ill, making Anne very stressed. In reality, she may have been unusually stressed on the day you first met her. If you had met her at a time when her stress level was lower, you could have thought that she is a really nice person. But chances are, your impression that she is rude and unhelpful will not change even when you hear about her mother. Instead, this new piece of information will be added to the first one: She is rude, unhelpful, and her mother is sick.

As a manager, you can protect yourself against this tendency by being aware of it and making a conscious effort to open your mind to new information. It would also be to your advantage to pay careful attention to the first impressions you create, particularly during job interviews.

Key Takeaway

Perception is how we make sense of our environment in response to environmental stimuli. While perceiving our surroundings, we go beyond the objective information available to us and our perception is affected by our values, needs, and emotions. There are many biases that affect human perception of objects, self, and others. When perceiving the physical environment, we fill in the gaps and extrapolate from the available information. When perceiving others, stereotypes influence our behavior. Stereotypes may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies. Stereotypes are perpetuated because of our tendency to pay selective attention to aspects of the environment and ignore information inconsistent with our beliefs. Understanding the perception process gives us clues to understanding human behavior.

Exercises

- What are some of the typical errors, or optical illusions, that we experience when we observe physical objects?

- What are the problems of false consensus error? How can managers deal with this tendency?

- Describe a situation where perception biases have or could affect any of the P-O-L-C facets. Use an example you have experienced or observed, or, if you do not have such an example, create a hypothetical situation. How do we manage the fact that human beings develop stereotypes? Is there such as thing as a good stereotype? How would you prevent stereotypes from creating unfairness in management decisions?

- Describe a self-fulfilling prophecy you have experienced or observed in action. Was the prophecy favorable or unfavorable? If unfavorable, how could the parties have chosen different behavior to produce a more positive outcome?

Work Attitudes and Job Satisfaction

Our behavior at work often depends on how we feel about being there. Therefore, making sense of how people behave depends on understanding their work attitudes. An attitude refers to our opinions, beliefs, and feelings about aspects of our environment. We have attitudes toward the food we eat, people we interact with, courses we take, and various other things. At work, two particular job attitudes have the greatest potential to influence how we behave. These are job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Job satisfaction refers to the feelings people have toward their job. If the number of studies conducted on job satisfaction is an indicator, job satisfaction is probably the most important job attitude. Institutions such as Gallup Inc. or the Society of Human Resource Management (SHRM) periodically conduct studies of job satisfaction to track how satisfied employees are at work. According to a recent Gallup survey, 90% of the employees surveyed said that they were at least somewhat satisfied with their jobs. The recent SHRM study revealed 40% who were very satisfied.What keeps employees satisfied? (2007, August). HR Focus, pp. 10–13; Sandberg, J. (2008, April 15). For many employees, a dream job is one that isn’t a nightmare. Wall Street Journal, p. B1. Organizational commitment is the emotional attachment people have toward the company they work for. There is a high degree of overlap between job satisfaction and organizational commitment, because things that make us happy with our job often make us more committed to the company as well. Companies believe that these attitudes are worth tracking because they are often associated with important outcomes such as performance, helping others, absenteeism, and turnover.

How strong is the attitude-behavior link? First of all, it depends on the attitude in question. Your attitudes toward your colleagues may influence whether you actually help them on a project, but they may not be a good predictor of whether you will quit your job. Second, it is worth noting that attitudes are more strongly related to intentions to behave in a certain way, rather than actual behaviors. When you are dissatisfied with your job, you may have the intention to leave. Whether you will actually leave is a different story! Your leaving will depend on many factors, such as availability of alternative jobs in the market, your employability in a different company, and sacrifices you have to make while changing jobs. In other words, while attitudes give us hints about how a person might behave, it is important to remember that behavior is also strongly influenced by situational constraints.

OB Toolbox: How Can You Be Happier at Work?

- Have a positive attitude about it. Your personality is a big part of your happiness. If you are always looking for the negative side of everything, you will find it.

- A good fit with the job and company is important to your happiness. This starts with knowing yourself: What do you want from the job? What do you enjoy doing? Be honest with yourself and do a self-assessment.

- Get accurate information about the job and the company. Ask detailed questions about what life is like in this company. Do your research: Read about the company, and use your social network to understand the company’s culture.

- Develop good relationships at work. Make friends. Try to get a mentor. Approach a person you admire and attempt to build a relationship with this person. An experienced mentor can be a great help in navigating life at a company. Your social network can help you weather the bad days and provide you emotional and instrumental support during your time at the company as well as afterward.

- Pay is important, but job characteristics matter more to your job satisfaction. Don’t sacrifice the job itself for a little bit more money. When choosing a job, look at the level of challenge, and the potential of the job to make you engaged.

- Be proactive in managing organizational life. If the job is stressful, cope with it by effective time management and having a good social network, as well as being proactive in getting to the source of stress. If you don’t have enough direction, ask for it!

- Know when to leave. If the job makes you unhappy over an extended period of time and there is little hope of solving the problems, it may be time to look elsewhere.

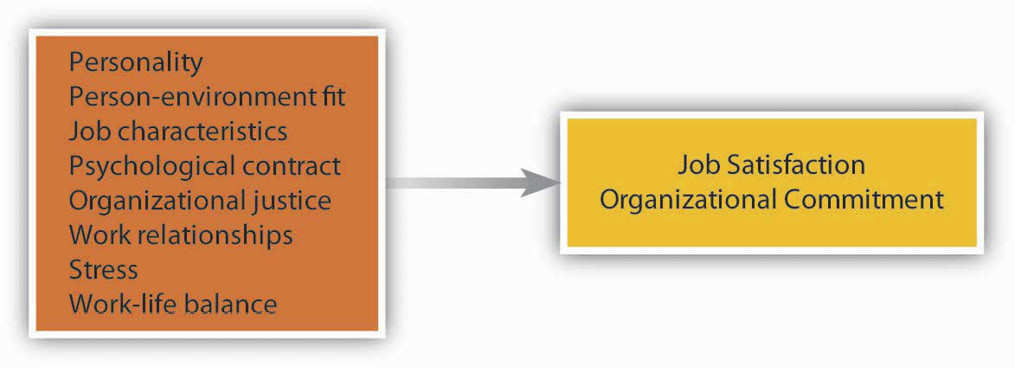

What Causes Positive Work Attitudes?

What makes you satisfied with your job and develop commitment to your company? Research shows that people pay attention to several aspects of their work environment, including how they are treated, the relationships they form with colleagues and managers, and the actual work they perform. We will now summarize the factors that show consistent relations with job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Figure 8).

Personality — Can assessing the work environment fully explain how satisfied we are on the job? Interestingly, some experts have shown that job satisfaction is not purely environmental and is partially due to our personality. Some people have a disposition to be happy in life and at work regardless of environmental factors.

It seems that people who have a positive affective disposition (those who have a tendency to experience positive moods more often than negative moods) tend to be more satisfied with their jobs and more committed to their companies, while those who have a negative disposition tend to be less satisfied and less committed.1 This is not surprising, as people who are determined to see the glass as half full will notice the good things in their work environment, while those with the opposite character will find more things to complain about. In addition to our affective disposition, people who have a neurotic personality (those who are moody, temperamental, critical of themselves and others) are less satisfied with their job, while those who are emotionally more stable tend to be more satisfied. Other traits such as conscientiousness, self-esteem, locus of control, and extraversion are also related to positive work attitudes.2 Either these people are more successful in finding jobs and companies that will make them happy and build better relationships at work, which would increase their satisfaction and commitment, or they simply see their environment as more positive—whichever the case, it seems that personality is related to work attitudes.

Person–Environment Fit — The fit between what we bring to our work environment and the environmental demands influences our work attitudes. Therefore, person–job fit and person–organization fit are positively related to job satisfaction and commitment. When our abilities match job demands and our values match company values, we tend to be more satisfied with our job and more committed to the company we work for.3

Job Characteristics — The presence of certain characteristics on the job seems to make employees more satisfied and more committed. Using a variety of skills, having autonomy at work, receiving feedback on the job, and performing a significant task are some job characteristics that are related to satisfaction and commitment. However, the presence of these factors is not important for everyone. Some people have a high growth need. They expect their jobs to help them build new skills and improve as an employee. These people tend to be more satisfied when their jobs have these characteristics.4

Psychological Contract — After accepting a job, people come to work with a set of expectations. They have an understanding of their responsibilities and rights. In other words, they have a psychological contract with the company. A psychological contract is an unwritten understanding about what the employee will bring to the work environment and what the company will provide in exchange. When people do not get what they expect, they experience a psychological contract breach, which leads to low job satisfaction and commitment. Imagine that you were told before being hired that the company was family friendly and collegial. However, after a while, you realize that they expect employees to work 70 hours a week, and employees are aggressive toward each other. You are likely to experience a breach in your psychological contract and be dissatisfied. One way of preventing such problems is for companies to provide realistic job previews to their employees.5

Organizational Justice — A strong influence over our satisfaction level is how fairly we are treated. People pay attention to the fairness of company policies and procedures, treatment from supervisors, and pay and other rewards they receive from the company.6

Relationships at Work — Two strong predictors of our happiness at work and commitment to the company are our relationships with coworkers and managers. The people we interact with, their degree of compassion, our level of social acceptance in our work group, and whether we are treated with respect are all important factors surrounding our happiness at work. Research also shows that our relationship with our manager, how considerate the manager is, and whether we build a trust-based relationship with our manager are critically important to our job satisfaction and organizational commitment.7 When our manager and upper management listen to us, care about us, and value our opinions, we tend to feel good at work. Even small actions may show employees that the management cares about them. For example, Hotel Carlton in San Francisco was recently taken over by a new management group. One of the small things the new management did created dramatic results. In response to an employee attitude survey, they replaced the old vacuum cleaners housekeepers were using and established a policy of replacing them every year. This simple act of listening to employee problems and taking action went a long way to making employees feel that the management cares about them.8

Consequences of Positive Work Attitudes

Why do we care about the job satisfaction and organizational commitment of employees? What behaviors would you expect to see from someone who has more positive work attitudes?

If you say “higher performance,” you have stumbled upon one of the most controversial subjects in organizational behavior. Many studies have been devoted to understanding whether happy employees are more productive. Some studies show weak correlations between satisfaction and performance while others show higher correlations (what researchers would call “medium-sized” correlations of 0.30).9 Even with a correlation of 0.30 though, the relationship may be lower than you may have expected. Why is this so?

It seems that happy workers have an inclination to be more engaged at work. They may want to perform better. They may be more motivated. But there are also exceptions. Think about this: Just because you want to perform, will you actually be a higher performer? Chances are that your skill level in performing the job will matter. There are also some jobs where performance depends on factors beyond an employee’s control, such as the pace of the machine they are working on. Because of this reason, in professional jobs such as engineering and research, we see a higher link between work attitudes and performance, as opposed to manual jobs such as assembly line work.10 Also, think about the alternative possibility: If you don’t like your job, does this mean that you will reduce your performance? Maybe up to a certain point, but there will be factors that prevent you from reducing your performance: the fear of getting fired, the desire to get a promotion so that you can get out of the job that you dislike so much, or your professional work ethic. As a result, we should not expect a one-to-one relationship between satisfaction and performance. Still, the observed correlation between work attitudes and performance is important and has practical value.

Work attitudes are even more strongly related to organizational citizenship behaviors (behaviors that are not part of our job but are valuable to the organization, such as helping new employees or working voluntary overtime). Satisfied and committed people are absent less frequently and for shorter duration, are likely to stay with a company longer, and demonstrate less aggression at work. Just as important, people who are happy at work are happier with their lives overall. Given that we spend so much of our waking hours at work, it is no surprise that our satisfaction with our job is a big part of how satisfied we feel about life in general.11

Assessing Work Attitudes in the Workplace

Given that work attitudes may give us clues as to who will leave or stay, who will perform better, and who will be more engaged, tracking satisfaction and commitment levels is a helpful step for companies. If there are companywide issues that make employees unhappy and disengaged, then these issues need to be resolved. There are at least two systematic ways in which companies can track work attitudes: through attitude surveys and exit interviews. Companies such as KFC Corporation and Long John Silver’s Inc. restaurants, the SAS Institute, Google, and others give periodic surveys to employees to track their work attitudes. Companies can get more out of these surveys if responses are held confidential. If employees become concerned that their individual responses will be shared with their immediate manager, they are less likely to respond honestly. Moreover, the success of these surveys depends on the credibility of management in the eyes of employees. If management periodically collects these surveys but no action comes out of them, employees may adopt a more cynical attitude and start ignoring these surveys, hampering the success of future efforts.

An exit interview involves a meeting with the departing employee. This meeting is often conducted by a member of the human resource management department. The departing employee’s manager is the worst person to conduct the interview, because managers are often one of the primary reasons an employee is leaving in the first place. If conducted well, this meeting may reveal what makes employees dissatisfied at work and give management clues about areas for improvement.

Key Takeaway

Work attitudes are the feelings we have toward different aspects of the work environment. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment are two key attitudes that are the most relevant to important outcomes. Attitudes create an intention to behave in a certain way and may predict actual behavior under certain conditions. People develop positive work attitudes as a result of their personality, fit with their environment, stress levels they experience, relationships they develop, perceived fairness of their pay, company policies, interpersonal treatment, whether their psychological contract is violated, and the presence of policies addressing work–life conflict. When people have more positive work attitudes, they may have the inclination to perform better, display citizenship behaviors, and be absent less often and for shorter periods of time, and they are less likely to quit their jobs within a short period of time. When workplace attitudes are more positive, companies benefit in the form of higher safety and better customer service, as well as higher company performance.

Exercises

- What is the difference between job satisfaction and organizational commitment? Which do you think would be more strongly related to performance? Which would be more strongly related to turnover?

- Do you think making employees happier at work is a good way of motivating people? When would high satisfaction not be related to high performance?

- In your opinion, what are the three most important factors that make people dissatisfied with their job? What are the three most important factors relating to organizational commitment?

- How important is pay in making people attached to a company and making employees satisfied?

- Do you think younger and older people are similar in what makes them happier at work and committed to their companies? Do you think there are male–female differences? Explain your answers.

Work Behaviors

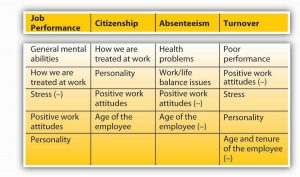

One of the important objectives of the field of organizational behavior is to understand why people behave the way they do. Which behaviors are we referring to here? We will focus on four key work behaviors: job performance, organizational citizenship behaviors, absenteeism, and turnover. These are not the only behaviors OB is concerned about, but understanding what is meant by these terms and understanding the major influences over each type of behavior will give you more clarity about analyzing the behaviors of others in the workplace. We summarize the major research findings about the causes of each type of behavior in the following figure (Figure 9).

Job Performance

Job performance, or in-role performance, refers to the performance level on factors included in the job description. For each job, the content of job performance may differ. Measures of job performance include the quality and quantity of work performed by the employee, the accuracy and speed with which the job is performed, and the overall effectiveness of the person performing the job. In many companies, job performance determines whether a person is promoted, rewarded with pay raises, given additional responsibilities, or fired from the job. Therefore, job performance is tracked and observed in many organizations and is one of the main outcomes studied in the field of organizational behavior.

What are the Major Predictors of Job Performance?

Under which conditions do people perform well, and what are the characteristics of high performers? These questions received a lot of research attention. It seems that the most powerful influence over our job performance is our general mental ability, or cognitive abilities. Our reasoning abilities, verbal and numerical skills, analytical skills, and overall intelligence level seems to be important across most situations. It seems that general mental ability starts influencing us early in life; it is strongly correlated with measures of academic success.12General mental ability is important for job performance across different settings, but there is also variation. In jobs with high complexity, it is much more critical to have high general mental abilities. In jobs such as working in sales, management, engineering, or other professional areas, this ability is much more important, whereas for jobs involving manual labor or clerical work, the importance of high mental abilities for high performance is weaker (yet still important).

How we are treated within an organization is another factor determining our performance level. When we feel that we are being treated fairly by a company, have a good relationship with our manager, have a manager who is supportive and rewards high performance, and we trust the people we work with, we tend to perform better. Why? It seems that when we are treated well, we want to reciprocate. Therefore, when we are treated well, we treat the company well by performing our job more effectively.13 Following the quality of treatment, the stress we experience determines our performance level. When we experience high levels of stress, our mental energies are drained. Instead of focusing on the task at hand, we start concentrating on the stressor and become distracted trying to cope with it. Because our attention and energies are diverted to deal with stress, our performance suffers. Having role ambiguity and experiencing conflicting role demands are related to lower performance.14 Stress that prevents us from doing our jobs does not have to be related to our experiences at work. For example, according to a survey conducted by Workplace Options, 45% of the respondents said that financial stress affects work performance. When people are in debt, are constantly worrying about mortgage or tuition payments, or are having trouble paying for essentials such as gas and food, their performance will suffer.15

Our work attitudes, specifically job satisfaction, are moderate correlates of job performance. When we are satisfied with the job, we may perform better. This relationship seems to exist in jobs with greater levels of complexity and weakens in simpler and less complicated jobs. It is possible that in less complex jobs, our performance depends more on the machinery we work with or organizational rules and regulations. In other words, people may have less leeway to reduce performance in these jobs. Also, in some jobs people do not reduce their performance even when dissatisfied. For example, among nurses there seems to be a weak correlation between satisfaction and performance. Even when they are unhappy, nurses put substantial effort into their work, likely because they feel a moral obligation to help their patients.16

Organizational Citizenship Behaviors

While job performance refers to the performance of duties listed in one’s job description, organizational citizenship behaviors involve performing behaviors that are more discretionary. Organizational citizenship behaviors (OCB) are voluntary behaviors employees perform to help others and benefit the organization. Helping a new coworker understand how things work in your company, volunteering to organize the company picnic, and providing suggestions to management about how to improve business processes are some examples of citizenship behaviors. These behaviors contribute to the smooth operation of business.

What are the major predictors of citizenship behaviors? Unlike performance, citizenship behaviors do not depend so much on one’s abilities. Job performance, to a large extent, depends on our general mental abilities. When you add the education, skills, knowledge, and abilities that are needed to perform well, the role of motivation in performance becomes more limited. As a result, someone being motivated will not necessarily translate into a person performing well. For citizenship behaviors, the motivation-behavior link is clearer. We help others around us if we feel motivated to do so. Finally, job performance has a modest relationship with personality, particularly conscientiousness. People who are organized, reliable, dependable, and achievement-oriented seem to outperform others in various contexts.17

Perhaps the most important factor explaining our citizenship behaviors is how we are treated by the people around us. When we have a good relationship with our manager and we are supported by management staff, when we are treated fairly, when we are attached to our peers, and when we trust the people around us, we are more likely to engage in citizenship behaviors. A high-quality relationship with people we work with will mean that simply doing our job will not be enough to maintain the relationship. In a high-quality relationship, we feel the obligation to reciprocate and do extra things to help those around us.18

Our personality is yet another explanation for why we perform citizenship behaviors. Personality is a modest predictor of actual job performance but a much better predictor of citizenship. People who are conscientious, agreeable, and have positive affectivity tend to perform citizenship behaviors more often than others.19

Job attitudes are also moderately related to citizenship behaviors. People who are happier at work, those who are more committed to their companies, and those who have overall positive attitudes toward their work situation tend to perform citizenship behaviors more often than others. When people are unhappy, they tend to be disengaged from their jobs and rarely go beyond the minimum that is expected of them.20 Interestingly, age seems to be related to the frequency with which we demonstrate citizenship behaviors. People who are older are better citizens. It is possible that with age, we gain more experiences to share. It becomes easier to help others because we have more accumulated company and life experiences to draw from.21

Key Takeaway

Employees demonstrate a wide variety of positive and negative behaviors at work. Among these behaviors, four are critically important and have been extensively studied in the OB literature. Job performance is a person’s accomplishments of tasks listed in one’s job description. A person’s abilities, particularly mental abilities, are the main predictor of job performance in many occupations. How we are treated at work, the level of stress experienced at work, work attitudes, and, to a lesser extent, our personality are also factors relating to one’s job performance. Citizenship behaviors are tasks helpful to the organization but are not in one’s job description. Performance of citizenship behaviors is less a function of our abilities and more of motivation. How we are treated at work, personality, work attitudes, and our age are the main predictors of citizenship. Among negative behaviors, absenteeism and turnover are critically important. Health problems and work–life balance issues contribute to more absenteeism. Poor work attitudes are also related to absenteeism, and younger employees are more likely to be absent from work. Turnover is higher among low performers, people who have negative work attitudes, and those who experience a great deal of stress. Personality and youth are personal predictors of turnover.

Exercises

- What is the difference between performance and organizational citizenship behaviors? How would you increase someone’s performance? How would you increase citizenship behaviors?

- Are citizenship behaviors always beneficial to the company? If not, why not? Can you think of any citizenship behaviors that employees may perform with the intention of helping a company but that may have negative consequences overall?

- Given the factors correlated with job performance, how would you identify future high performers?

- What are the major causes of absenteeism at work? How can companies minimize the level of absenteeism that takes place?

- In some companies, managers are rewarded for minimizing the turnover within their department or branch. A part of their bonus is tied directly to keeping the level of turnover below a minimum. What do you think about the potential effectiveness of these programs? Do you see any downsides to such programs?

References: Personality and Values

Ahearne, M., Mathieu, J., & Rapp, A. (2005). To empower or not to empower your sales force? An empirical examination of the influence of leadership empowerment behavior on customer satisfaction and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 945–955.

Baer, M., & Oldham, G. R. (2006). The curvilinear relation between experienced creative time pressure and creativity: Moderating effects of openness to experience and support for creativity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 963–970.

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44, 1–26.

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1993). Autonomy as a moderator of the relationships between the big five personality dimensions and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 111–118.

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1996). Effects of impression management and self-deception on the predictive validity of personality constructs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 261–272.

Barrick, M. R., Patton, G. K., & Haugland, S. N. (2000). Accuracy of interviewer judgments of job applicant personality traits. Personnel Psychology, 53, 925–951.

Bauer, T. N. (2005). Enhancing career benefits of employee proactive personality: The role of fit with jobs and organizations. Personnel Psychology, 58, 859–891.

Bauer, T. N., Bodner, T., Erdogan, B., Truxillo, D. M., & Tucker, J. S. (2007). Newcomer adjustment during organizational socialization: A meta-analytic review of antecedents, outcomes, and methods. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 707–721.

Bauer, T. N., Erdogan, B., Liden, R. C., & Wayne, S. J. (2006). A longitudinal study of the moderating role of extraversion: Leader-member exchange, performance, and turnover during new executive development. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 298–310.

Bono, J. E., & Judge, T. A. (2004). Personality and transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 901–910.

Brown, D. J., Cober, R. T., Kane, K., Levy, P. E., & Shalhoop, J. (2006). Proactive personality and the successful job search: A field investigation with college graduates. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 717–726.

Caldwell, D. F., & Burger, J. M. (1998). Personality characteristics of job applicants and success in screening interviews. Personnel Psychology, 51, 119–136.

Certo, S. T., & Certo, S. C. (2005). Spotlight on entrepreneurship. Business Horizons, 48, 271–274.

Chan, D. (2006). Interactive effects of situational judgment effectiveness and proactive personality on work perceptions and work outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 475–481Erdogan, B., &

Connolly, J. J., & Viswesvaran, C. (2000). The role of affectivity in job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 29, 265–281.

Crant, M. J. (1995). The proactive personality scale and objective job performance among real estate agents. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 532–537.

Day, D. V., Schleicher, D. J., Unckless, A. L., & Hiller, N. J. (2002). Self-monitoring personality at work: A meta-analytic investigation of construct validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 390–401.

Dunn, W. S., Mount, M. K., Barrick, M. R., & Ones, D. S. (1995). Relative importance of personality and general mental ability in managers’ judgments of applicant qualifications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 500–509.

Emmett, A. (2004, October). Snake oil or science? That’s the raging debate on personality testing. Workforce Management, 83, 90–92.

Erdogan, B., & Bauer, T. N. (2005). Enhancing career benefits of employee proactive personality: The role of fit with jobs and organizations. Personnel Psychology, 58, 859–891.

Fields, J. M., & Schuman, H. (1976). Public beliefs about the beliefs of the public. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 40 (4), 427–448.

George, J. M., & Jones, G. R. (1996). The experience of work and turnover intentions: Interactive effects of value attainment, job satisfaction, and positive mood. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 318–325.

Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative “description of personality”: The big-five factor structure. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 59, 1216–1229.

Heller, M. (2005, September). Court ruling that employer’s integrity test violated ADA could open door to litigation. Workforce Management, 84 (9), 74–77.

Higgins, E. T., & Bargh, J. A. (1987). Social cognition and social perception. Annual Review of Psychology, 38, 369–425.

Ilies, R., Scott, B. A., & Judge, T. A. (2006). The interactive effects of personal traits and experienced states on intraindividual patterns of citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 561–575.

Jawahar, I. M. (2001). Attitudes, self-monitoring, and appraisal behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 875–883.

John, O. P., & Robins, R. W. (1994). Accuracy and bias in self-perception: Individual differences in self-enhancement and the role of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 206–219.

Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—self esteem, generalized self efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 80–92.

Judge, T. A., & Bretz, R. D. (1992). Effects of work values on job choice decisions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 261–271.

Judge, T. A., & Higgins, C. A. (1999). The big five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Personnel Psychology, 52, 621–652.

Judge, T. A., & Ilies, R. (2002). Relationship of personality to performance motivation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 797–807.

Judge, T. A., Heller, D., & Mount, M. K. (2002). Five-factor model of personality and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 530–541.

Judge, T. A., Jackson, C. L., Shaw, J. C., Scott, B. A., & Rich, B. L. (2007). Self-efficacy and work-related performance: The integral role of individual differences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 107–127.

Judge, T. A., Martocchio, J. J., & Thoresen, C. J. (1997). Five-factor model of personality and employee absence. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 745–755.

Judge, T. A. Heller, D., & Mount, M. K. (2002). Five-factor model of personality and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 530–541.

Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., & Wanberg, C. R. (2003). Unwrapping the organizational entry process: Disentangling multiple antecedents and their pathways to adjustment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 779–794.

Kellman, P. J., & Shipley, T. F. (1991). A theory of visual interpolation in object perception. Cognitive Psychology, 23, 141–221.

Keltner, D., Ellsworth, P. C., & Edwards, K. (1993). Beyond simple pessimism: Effects of sadness and anger on social perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 740–752.

Klein, K. J., Beng-Chong, L., Saltz, J. L., & Mayer, D. M. (2004). How do they get there? An examination of the antecedents of centrality in team networks. Academy of Management Journal, 47, 952–963.

LePine, J. A. (2003). Team adaptation and postchange performance: Effects of team composition in terms of members’ cognitive ability and personality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 27–39.

LePine, J. A., & Van Dyne, L. (2001). Voice and cooperative behavior as contrasting forms of contextual performance: Evidence of differential relationships with big five personality characteristics and cognitive ability. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 326–336.

Lievens, F., Harris, M. M., Van Keer, E., & Bisqueret, C. (2003). Predicting cross-cultural training performance: The validity of personality, cognitive ability, and dimensions measured by an assessment center and a behavior description interview. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 476–489.

Lord, C. G., Ross, L., & Lepper, M. R. (1979) Biased assimilation and attitude polarization: The effects of prior theories on subsequently considered evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 2098–2109.

Lusk, E. J., & Oliver, B. L. (1974). Research notes. American manager’s personal value systems-revisited. Academy of Management Journal, 17 (3), 549–554.

Major, D. A., Turner, J. E., & Fletcher, T. D. (2006). Linking proactive personality and the big five to motivation to learn and development activity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 927–935.

Mayer, D., Nishii, L., Schneider, B., & Goldstein, H. (2007). The precursors and products of justice climates: Group leader antecedents and employee attitudinal consequences. Personnel Psychology, 60, 929–963.

Morgeson, F. P., Campion, M. A., Dipboye, R. L., Hollenbeck, J. R., Murphy, K., & Schmitt, N. (2007). Are we getting fooled again? Coming to terms with limitations in the use of personality tests for personnel selection. Personnel Psychology, 60, 1029–1049.

Morgeson, F. P., Campion, M. A., Dipboye, R. L., Hollenbeck, J. R., Murphy, K., & Schmitt, N. (2007). Reconsidering the use of personality tests in personnel selection contexts. Personnel Psychology, 60, 683–729.

Mount, M. K., Barrick, M. R., & Strauss, J. P. (1994). Validity of observer ratings of the big five personality factors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 79, 272–280.

Ones, D. S., Dilchert, S., Viswesvaran, C., & Judge, T. A. (2007). In support of personality assessment in organizational settings. Personnel Psychology, 60, 995–1027.

Ones, D. S., Viswesvaran, C., & Reiss, A. D. (1996). Role of social desirability in personality testing for personnel selection. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 660–679.

Phillips, J. M., & Gully, S. M. (1997). Role of goal orientation, ability, need for achievement, and locus of control in the self-efficacy and goal-setting process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 792–802.

Ravlin, E. C., & Meglino, B. M. (1987). Effect of values on perception and decision making: A study of alternative work values measures. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72, 666–673.