8

Essential Questions:

- What is the impact of ethical behavior on the modern workplace?

- What are some models that one can use to make ethical decisions?

- What are examples of personal ethics? Corporate ethics?

- What are the different types of power?

- How can one use power to influence others?

- What are the aspects of personal power one can use to manage impressions?

Job Attitudes, Behaviors, and Ethics

People prefer to work in companies that have an ethical environment. Studies show that when an organization has a moral climate that values doing the right thing, people tend to be happier at work, more committed to their companies, and less likely to want to leave. In other words, in addition to increasing the frequency of ethical behaviors, the presence of an ethical climate will attach people to a company. An ethical climate is related to performing citizenship behaviors in which employees help each other and their supervisors, and perform many behaviors that are not part of their job descriptions.1 If people are happy at work and committed to the company, do they behave more ethically? This connection is not as clear. In fact, loving your job and being committed to the company may prevent you from realizing that the company is doing anything wrong. One study showed that, when people were highly committed to their company, they were less likely to recognize organizational wrongdoing and less likely to report the problem to people within the organization. Whistleblowers, or people who reported wrongdoing, were more likely to have moderate levels of commitment to the company. It is possible that those people who identify with a company are blind to its faults.2 Companies trying to prevent employees from behaving unethically face a dilemma. One way of reducing unethical behaviors is to monitor employees closely. However, when people are closely monitored through video cameras, when their e-mails are routinely read, and when their online activities are closely monitored, employees are more likely to feel that they are being treated unfairly and with little respect. Therefore, high levels of employee monitoring, while reducing the frequency of unethical behaviors, may reduce job satisfaction and commitment, as well as work performance and citizenship behaviors. Instead of monitoring and punishing employees, organizations can reduce unethical behavior by creating an ethical climate and making ethics a shared value.3

Be Ethical at Work

You can fool some of the people all of the time, and all of the people some of the time, but you cannot fool all of the people all the time.

Abraham Lincoln

Integrity is doing the right thing, even if nobody is watching.

Unknown author

Case: Unethical or the “Way We Do Business”?

As the assistant manager at an automotive parts department, Jeremy has lots of experience with cars and the automotive parts business. Everyone has their own preference for car part brand, including him. When he works with customers, he might show them the other brand but tends to know more about his favorite brands and shows those brands more often. However, at the new product training seminar three weeks ago, all managers were told they will receive a bonus for every DevilsDeat brake pad they or their employees sell. Employees would also receive a bonus. Furthermore, it was recommended that managers train their employees only on the DevilsDeat products, so the managers and employees alike could earn a higher salary. Personally, Jeremy feels DevilsDeat brake pads are inferior and has had several products malfunction on him. But the company ordered this to be done, so Jeremy trained his employees on the products when he returned to the store.

Last week, a customer came in and said his seventeen-year-old daughter had been in an accident. The store had sold a defective DevilsDeat brake pad, and his daughter was almost killed. Jeremy apologized profusely and replaced the part for free. Three more times that week customers came in upset their DevilsDeat products had malfunctioned. Jeremy replaced them each time but began to feel really uncomfortable with the encouragement of selling an inferior product.

Jeremy called to discuss with the district manager, who told him it was just a fluke, so Jeremy continued on as usual. Several months later, a lawsuit was filed against DevilsDeat and Jeremy’s automotive parts chain because of three fatalities as a result of the brake pads.

This story is a classic one of conflicting values between a company and an employee. This chapter will discuss some of the challenges associated with conflicting values, social responsibility of companies, and how to manage this in the workplace.

What is Ethics?

Before we begin our conversation on ethics, it is important to note that making ethical decisions is an emotional intelligence skill, specifically self-management. We know that our emotional intelligence skills contribute to our career success, so learning how to make ethical decisions is imperative to development of this human relations skill.

First, though, what exactly is ethics? Ethics is defined as a set of values that define right and wrong. Can you see the challenge with this ambiguous definition? What exactly is right and wrong? That obviously depends on the person and the individual situation, which is what makes ethics difficult to more specifically define. Values are defined as principles or standards that a person finds desirable. So we can say that ethics is a set of principles that a person or society finds desirable and help define right and wrong. Often people believe that the law defines this for us. To an extent it does, but there are many things that could be considered unethical that are not necessarily illegal. For example, take the popularized case where a reality production crew was filming about alcoholism — a show called Intervention. They followed one woman who got behind the wheel to drive and obviously was in no state to do so. The television crew let her drive. People felt this was extremely unethical, but it wasn’t illegal because they were viewed as witnesses and therefore had no legal duty to intervene.4 This is the difference between something ethical and illegal. Something may not necessarily be illegal, but at the same time, it may not be the right thing to do.

Levels of Ethics: An Organizational Framework

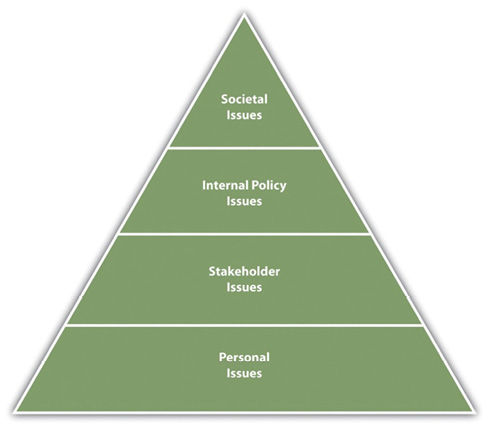

While there may appear to be a difference in ethics between individuals and the organization, often individuals’ ethics are shown through the ethics of an organization, since individuals are the ones who set the ethics to begin with.5 In other words, while we can discuss organizational ethics, remember that individuals are the ones who determine organizational ethics, which ties the conversation of organizational ethics into personal ethics as well. If an organization can create an ethically oriented culture, it is more likely to hire people who behave ethically.6 This behavior is part of human relations, in that having and maintaining good ethics is part of emotional intelligence. Of our four levels of ethics discussed next, the first two may not apply to us directly as individuals in the company. As possible leaders of an organization, however, presenting all four in this section is necessary for context.

There are four main levels of ethical levels within organizations (Figure 1).7 The first level is societal issues. These are the top-level issues relating to the world as a whole, which deal with questions such as the morality of child labor worldwide. Deeper-level societal issues might include the role (if any) of capitalism in poverty, for example. Most companies do not operate at this level of ethics, although some companies, such as Tom’s Shoes, feel it is their responsibility to ensure everyone has shoes to wear. As a result, their “one for one” program gives one pair of shoes to someone in need for every pair of shoes purchased. Concern for the environment, for example, would be another way a company can focus on societal-level issues. This level of ethics involves areas of emotional intelligence we have discussed, specifically, an individual’s empathy and social awareness. Many companies take a stand on societal ethics in part for marketing but also in part because of the ethics the organization creates due to the care and concern for individuals.

Our second level of ethics is stakeholder’s issues. A stakeholder is anyone affected by a company’s actions. In this level, businesses must deal with policies that affect their customers, employees, suppliers, and people within the community. For example, this level might deal with fairness in wages for employees or notification of the potential dangers of a company’s product. For example, McDonald’s was sued in 2010 because the lure of Happy Meal toys were said to encourage children to eat unhealthy food.8 This is a stakeholder issue for McDonald’s, since it affects customers. Although the case was dismissed in April 2012, the stakeholder issue revolves around the need for companies to balance healthy choices and its marketing campaigns.9

The third level is the internal policy issue level of ethics. In this level, the concern is internal relationships between a company and employees. Fairness in management, pay, and employee participation would all be considered ethical internal policy issues. If we work in management at some point in our careers, this is certainly an area we will have extensive control over. Creation of policies that relate to the treatment of employees relates to human relations — and retention of those employees through fair treatment. It is in the organization’s best interests to create policies around internal policies that benefit the company, as well as the individuals working for them.

The last level of ethical issues is personal issues. These deal with how we treat others within our organization. For example, gossiping at work or taking credit for another’s work would be considered personal issues. As an employee of an organization, we may not have as much control over societal and stakeholder issues, but certainly we have control over the personal issues level of ethics. This includes “doing the right thing.” Doing the right thing affects our human relations in that if we are shown to be trustworthy when making ethical decisions, it is more likely we can be promoted, or at the very least, earn respect from our colleagues. Without this respect, our human relations with coworkers can be impacted negatively.

One of the biggest ethical challenges in the workplace is when our company’s ethics do not meet our own personal ethics. For example, suppose you believe strongly that child labor should not be used to produce clothing. You find out, however, that your company uses child labor in China to produce 10 percent of your products. In this case, your personal values do not meet the societal and stakeholder values you find important. This kind of difference in values can create challenges working in a particular organization. When choosing the company or business we work for, it is important to make sure there is a match between our personal values and the values within the organization.

How important is it for you to work for an organization that has values and ethics similar to yours?

Sources of Personal Ethics

People are not born with a set of values. The values are developed during the aging process. We can gain our values by watching others, such as parents, teachers, mentors, and siblings. The more we identify with someone, say, our parents, the more likely we are to model that person’s behavior. For example, if Jenny sees her father frequently speed when driving on the highway, there is a good chance she will model that behavior as an adult. Or perhaps because of this experience, Jenny ends up doing the exact opposite and always drives the speed limit. Either way, this modeling experience affected her viewpoint. Likewise, if Jenny hears her mother frequently speak ill of people or hears her lying to get out of attending events, there is a good chance Jenny may end up doing the same as an adult — or the opposite. Besides our life models, other things that can influence our values are the following:

- Religion. Religion has an influence over what is considered right and wrong. Religion can be the guiding force for many people when creating their ethical framework.

- Culture. Every culture has a societal set of values. For example, in Costa Rica living a “pure life” (Pura Vita) is the country’s slogan. As a result of this laid back attitude, the culture focuses on a loose concept of time compared to the United States, for example. Similar to our models, our culture tells us what is good, right, and moral. In some cultures where corruption and bribery is the normal way of doing business, people in the culture have the unspoken code that bribery is the way to get what you want. For example, in India, China, and Russia, exporters pay bribes more often than companies from other countries, according to the New York Times.10In Europe, Italian businesses are more apt to pay bribes compared to other European Union countries. While bribery of a government official is illegal in many countries, it can happen anyway. For example, the government officials, such as police, may view themselves as underpaid and therefore find it acceptable to accept bribes from people who have broken the law.

- Media. Advertising shows us what our values “should” be. For example, if Latrice watches TV on a Thursday night, advertisements for skin creams and hair products might tell her that good skin and shiny hair are a societal value, so she should value those things, too.

- Models. Our parents, siblings, mentors, coaches, and others can affect our ethics today and later in life. The way we see them behave and the things they say affect our values.

- Attitudes. Our attitudes, similar to values, start developing at a young age. As a result, our impression, likes, and dislikes affect ethics, too. For example, someone who spends a lot of time outdoors may feel a connection to the environment and try to purchase environmentally friendly products.

- Experiences. Our values can change over time depending on the experiences we have. For example, if we are bullied by our boss at work, our opinion might change on the right way to treat people when we become managers.

Sources of Company Ethics

Since we know that everyone’s upbringing is different and may have had different models, religion, attitudes, and experiences, companies create policies and standards to ensure employees and managers understand the expected ethics. These sources of ethics can be based on the levels of ethics, which we discussed earlier. Understanding our own ethics and company ethics can apply to our emotional intelligence skills in the form of self-management and managing our relationships with others. Being ethical allows us to have a better relationship with our supervisors and organizations.

For example, companies create values statements, which explain their values and are tied to company ethics. A values statement is the organization’s guiding principles, those things that the company finds important.

Examples of Ethical Situations

Have you found yourself having to make any of these ethical choices within the last few weeks?

- Cheating on exams

- Downloading music and movies from share sites

- Plagiarizing

- Breaking trust

- Exaggerating experience on a resume

- Using Facebook or other personal websites during company or class time

- Taking office supplies home

- Taking credit for another’s work

- Gossiping

- Lying on time cards

- Conflicts of interest

- Knowingly accepting too much change

- Calling in sick when you aren’t really sick

- Discriminating against people

- Taking care of personal business on company or class time

- Stretching the truth about a product’s capabilities to make the sale

- Divulging private company information

A company publicizes its values statements but often an internal code of conduct is put into place in order to ensure employees follow company values set forth and advertised to the public. The code of conduct is a guideline for dealing with ethics in the organization. The code of conduct can outline many things, and often companies offer training in one or more of these areas:

- Sexual harassment policy

- Workplace violence

- Employee privacy

- Misconduct off the job

- Conflicts of interest

- Insider trading

- Use of company equipment

- Company information nondisclosures

- Expectations for customer relationships and suppliers

- Policy on accepting or giving gifts to customers or clients

- Bribes

- Relationships with competition

Some companies have 1-800 numbers, run by outside vendors, that allow employees to anonymously inform about ethics violations within the company. Someone who informs law enforcement of ethical or illegal violations is called a whistleblower. For example, Dr. Mitchell Magid worked as an oral surgeon for Sanford Health in North Dakota. When he reported numerous safety violations, he claimed he was fired from his job. In an initial ruling, Dr. Magid was awarded $900,000 for the firing, although Sanford Health claims he was fired for other reasons and will appeal the case.12In the United States, several laws protect whistleblowers. For example, the Occupational Health and Safety Act (OSHA) protects whistleblowers when they report safety violations. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 has a whistleblower statute, which protects employees who whistleblows on wrongful financial dealings within an organization.13

Like a person, a company can have ethics and values that should be the cornerstone of any successful person. Understanding where our ethics come from is a good introduction into how we can make good personal and company ethical decisions. Ethical decision making ties into human relations through emotional intelligence skills, specifically, self-management and relationship management. The ability to manage our ethical decision-making processes can help us make better decisions, and better decisions result in higher productivity and improved human relations.

Key Takeaways

Ethics is defined as a set of values that define right and wrong. Values are standards or principles that a person finds desirable.

There are four levels of ethical issues. First, societal issues deal with bigger items such as taking care of the environment, capitalism, or embargos. Sometimes companies get involved in societal-level ethics based on their company policies — for example, not using child labor in overseas factories.

The second level of ethical issues is stakeholder issues. These are the things that a stakeholder might care about, such as product safety.

Internal policy issues are the third level of ethical issues. This includes things like pay and how employees are treated.

Personal issues, our last level of ethical issues, refer to how we treat others within our organization.

There are sources of personal ethics and sources of company ethics. Our personal sources of ethics may come from the models we had in our childhood, such as parents, or from experiences, religion, or culture. Companies use values statements and codes of ethics to ensure everyone is following the same ethical codes, since ethics vary from person to person.

Making Ethical Decisions

Now that we have working knowledge of ethics, it is important to discuss some of the models we can use to make ethical decisions. Understanding these models can assist us in developing our self-management skills and relationship management skills. These models will give you the tools to make good decisions, which will likely result in better human relations within your organization.

Note there are literally hundreds of models, but most are similar to the ones we will discuss. Most people use a combination of several models, which might be the best way to be thorough with ethical decision making. In addition, often we find ethical decisions to be quick. For example, if I am given too much change at the grocery store, I may have only a few seconds to correct the situation. In this case, our values and morals come into play to help us make this decision, since the decision making needs to happen fast.

The Twelve Questions Model

Laura Nash, an ethics researcher, created the Twelve Questions Model as a simple approach to ethical decision making.14 In her model, she suggests asking yourself questions to determine if you are making the right ethical decision. This model asks people to reframe their perspective on ethical decision making, which can be helpful in looking at ethical choices from all angles. Her model consists of the following questions:

Have you defined the problem accurately?

- How would you define the problem if you stood on the other side of the fence?

- How did this situation occur in the first place?

- To whom and what do you give your loyalties as a person and as a member of the company?

- What is your intention in making this decision?

- How does this intention compare with the likely results?

- Whom could your decision or action injure?

- Can you engage the affected parties in a discussion of the problem before you make your decision?

- Are you confident that your position will be as valid over a long period of time as it seems now?

- Could you disclose without qualms your decision or action to your boss, your family, or society as a whole?

- What is the symbolic potential of your action if understood? If misunderstood?

- Under what conditions would you allow exceptions to your stand?

Source: Nash, L. (1981). Ethics without the sermon. Howard Business Review, 59 79–90, accessed February 24, 2012, http://www.cs.bgsu.edu/maner/heuristics/1981Nash.htm

Consider the situation of Catha and her decision to take home a printer cartilage from work, despite the company policy against taking any office supplies home. She might go through the following process, using the Twelve Questions Model:

- My problem is that I cannot afford to buy printer ink, and I have the same printer at home. Since I do some work at home, it seems fair that I can take home the printer ink.

- If I am allowed to take this ink home, others may feel the same, and that means the company is spending a lot of money on printer ink for people’s home use.

- It has occurred due to the fact I have so much work that I need to take some of it home, and often I need to print at home.

- I am loyal to the company.

- My intention is to use the ink for work purposes only.

- If I take home this ink, my intention may show I am disloyal to the company and do not respect company policies.

- The decision could injure my company and myself, in that if I get caught, I may get in trouble. This could result in loss of respect for me at work.

- Yes, I could engage my boss and ask her to make an exception to the company policy, since I am doing so much work at home.

- No, I am not confident of this. For example, if I am promoted at work, I may have to enforce this rule at some point. It would be difficult to enforce if I personally have broken the rule before.

- I would not feel comfortable doing it and letting my company and boss know after the fact.

- The symbolic action could be questionable loyalty to the company and respect of company policies.

- An exception might be ok if I ask permission first. If I am not given permission, I can work with my supervisor to find a way to get my work done without having a printer cartridge at home.

As you can see from the process, Catha came to her own conclusion by answering the questions involved in this model. The purpose of the model is to think through the situation from all sides to make sure the right decision is being made.

As you can see in this model, first an analysis of the problem itself is important. Determining your true intention when making this decision is an important factor in making ethical decisions. In other words, what do you hope to accomplish and who can it hurt or harm? The ability to talk with affected parties upfront is telling. If you were unwilling to talk with the affected parties, there is a chance (because you want it kept secret) that it could be the wrong ethical decision. Also, looking at your actions from other people’s perspectives is a core of this model (see Figure 2).

Josephson Institute of Ethics’ Model

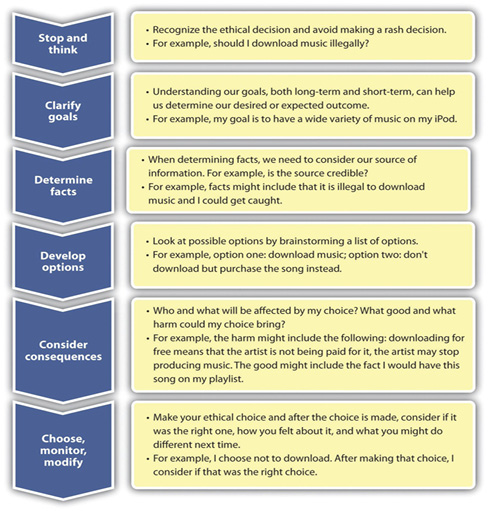

Josephson Institute of Ethics uses a model that focuses on six steps to ethical decision making. The steps consist of stop and think, clarify goals, determine facts, develop options, consider consequences, choose, and monitor/modify.

As mentioned, the first step is to stop and think. When we stop to think, this avoids rash decisions and allows us to focus on the right decision-making process. It also allows us to determine if the situation we are facing is legal or ethical. When we clarify our goals, we allow ourselves to focus on expected and desired outcomes. Next, we need to determine the facts in the situation. Where are we getting our facts? Is the person who is providing the facts to us credible? Is there bias in the facts or assumptions that may not be correct? Next, create a list of options. This can be a brainstormed list with all possible solutions. In the next step, we can look at the possible consequences of our actions. For example, who will be helped and who might be hurt? Since all ethical decisions we make may not always be perfect, considering how you feel and the outcome of your decisions will help you to make better ethical decisions in the future. Figure 3 gives an example of the ethical decision-making process using Josephson’s model.

Steps to Ethical Decision Making

There are many models that provide several steps to the decision-making process. One such model was created in the late 1990s for the counseling profession but can apply to nearly every profession from health care to business.15 In this model, the authors propose eight steps to the decision-making process. As you will note, the process is similar to Josephson’s model, with a few variations:

- Step 1: Identify the problem. Sometimes just realizing a particular situation is ethical can be the important first step. Occasionally in our organizations, we may feel that it’s just the “way of doing business” and not think to question the ethical nature.

- Step 2: Identify the potential issues involved. Who could get hurt? What are the issues that could negatively impact people and/or the company? What is the worst-case scenario if we choose to do nothing?

- Step 3: Review relevant ethical guidelines. Does the organization have policies and procedures in place to handle this situation? For example, if a client gives you a gift, there may be a rule in place as to whether you can accept gifts and if so, the value limit of the gift you can accept.

- Step 4: Know relevant laws and regulations. If the company doesn’t necessarily have a rule against it, could it be looked at as illegal?

- Step 5: Obtain consultation. Seek support from supervisors, coworkers, friends, and family, and especially seek advice from people who you feel are moral and ethical.

- Step 6: Consider possible and probable courses of action. What are all of the possible solutions for solving the problem? Brainstorm a list of solutions — all solutions are options during this phase.

- Step 7: List the consequences of the probable courses of action. What are both the positive and negative benefits of each proposed solution? Who can the decision affect?

- Step 8: Decide on what appears to be the best course of action. With the facts we have and the analysis done, choosing the best course of action is the final step. There may not always be a “perfect” solution, but the best solution is the one that seems to create the most good and the least harm.

Most organizations provide such a framework for decision making. By providing this type of framework, an employee can logically determine the best course of action. The Department of Defense uses a similar framework when making decisions, as shown in Note 5.14 “Department of Defense Decision-Making Framework”.

Department of Defense Decision-Making Framework

The Department of Defense uses a specific framework to make ethical decisions.

Define the problem.

- State the problem in general terms.

- State the decisions to be made.

- Identify the goals.

- State short-term goals.

- State long-term goals.

- List appropriate laws or regulations.

- List the ethical values at stake.

- Name all the stakeholders.

- Identify persons who are likely to be affected by a decision.

- List what is at stake for each stakeholder.

- Gather additional information.

- Take time to gather all necessary information.

- Ask questions.

- Demand proof when appropriate.

- Check your assumptions.

- State all feasible solutions.

- List solutions that have already surfaced.

- Produce additional solutions by brainstorming with associates.

- Note how stakeholders can be affected (loss or gain) by each solution.

- Eliminate unethical options.

- Eliminate solutions that are clearly unethical.

- Eliminate solutions with short-term advantages but long-term problems.

- Rank the remaining options according to how close they bring you to your goal, and solve the problem.

- Commit to and implement the best ethical solution.

Source: United States Department of Defense. (1999). Joint Ethics Regulation DoD 5500.7-R., accessed February 24, 2012, http://csweb.cs.bgsu.edu/maner/heuristics/1999USDepartmentOfDefense.htm and http://ogc.hqda.pentagon.mil/EandF/Documentation/ethics_material.aspx

Power and Politics

What Is Power?

We’ll look at the aspects and nuances of power in more detail in this chapter, but simply put, power is the ability to influence the behavior of others to get what you want. Gerald Salancik and Jeffery Pfeffer concur, noting, “Power is simply the ability to get things done the way one wants them to be done.”16 If you want a larger budget to open a new store in a large city and you get the budget increase, you have used your power to influence the decision.

Power distribution is usually visible within organizations. For example, Salancik and Pfeffer gathered information from a company with 21 department managers and asked 10 of those department heads to rank all the managers according to the influence each person had in the organization. Although ranking 21 managers might seem like a difficult task, all the managers were immediately able to create that list. When Salancik and Pfeffer compared the rankings, they found virtually no disagreement in how the top 5 and bottom 5 managers were ranked. The only slight differences came from individuals ranking themselves higher than their colleagues ranked them. The same findings held true for factories, banks, and universities.

Positive and Negative Consequences of Power

The fact that we can see and succumb to power means that power has both positive and negative consequences. On one hand, powerful CEOs can align an entire organization to move together to achieve goals. Amazing philanthropists such as Paul Farmer, a doctor who brought hospitals, medicine, and doctors to remote Haiti, and Greg Mortenson, a mountaineer who founded the Central Asia Institute and built schools across Pakistan, draw on their own power to organize others toward lofty goals; they have changed the lives of thousands of individuals in countries around the world for the better.17 On the other hand, autocracy can destroy companies and countries alike. The phrase, “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely” was first said by English historian John Emerich Edward Dalberg, who warned that power was inherently evil and its holders were not to be trusted. History shows that power can be intoxicating and can be devastating when abused, as seen in high-profile cases such as those involving Enron Corporation and government leaders such as the impeached Illinois Governor Rod Blagojevich in 2009. One reason that power can be so easily abused is because individuals are often quick to conform. To understand this relationship better, we will examine three famous researchers who studied conformity in a variety of contexts.

Conformity

Conformity refers to people’s tendencies to behave consistently with social norms. Conformity can refer to small things such as how people tend to face forward in an elevator. There’s no rule listed in the elevator saying which way to face, yet it is expected that everyone will face forward. To test this, the next time you’re in an elevator with strangers, simply stand facing the back of the elevator without saying anything. You may notice that those around you become uncomfortable. Conformity can result in engaging in unethical behaviors, because you are led by someone you admire and respect who has power over you. Guards at Abu Ghraib said they were just following orders when they tortured prisoners.18 People conform because they want to fit in with and please those around them. There is also a tendency to look to others in ambiguous situations, which can lead to conformity. The response to “Why did you do that?” being “Because everyone else was doing it” sums up this tendency.

So, does conformity occur only in rare or extreme circumstances? Actually, this is not the case. Three classic sets of studies illustrate how important it is to create checks and balances to help individuals resist the tendency to conform or to abuse authority. To illustrate this, we will examine findings from the Milgram, Asch, and Zimbardo studies.

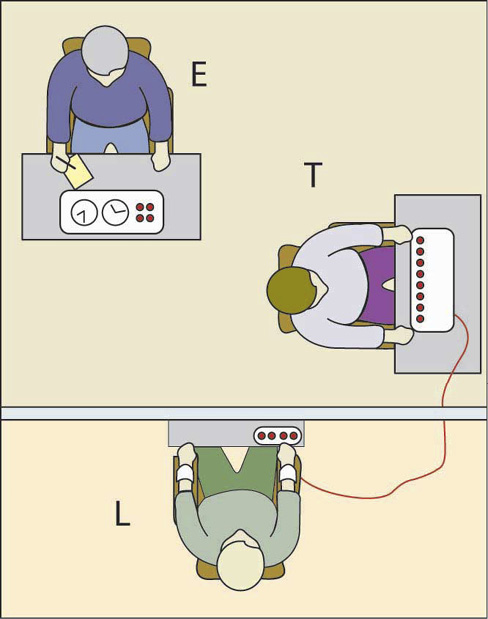

The Milgram Studies

Stanley Milgram, a psychologist at Yale in the 1960s, set out to study conformity to authority. His work tested how far individuals would go in hurting another individual when told to do so by a researcher. A key factor in the Milgram study and others that will be discussed is the use of confederates, or people who seem to be participants but are actually paid by the researchers to take on a certain role. Participants believed that they were engaged in an experiment on learning. The participant (teacher) would ask a series of questions to another “participant” (learner). The teachers were instructed to shock the learners whenever an incorrect answer was given. The learner was not a participant at all but actually a confederate who would pretend to be hurt by the shocks and yell out in pain when the button was pushed. Starting at 15 volts of power, the participants were asked to increase the intensity of the shocks over time. Some expressed concern when the voltage was at 135 volts, but few stopped once they were told by the researcher that they would not personally be held responsible for the outcome of the experiment and that their help was needed to complete the experiment. In the end, all the participants were willing to go up to 300 volts, and a shocking 65% were willing to administer the maximum of 450 volts even as they heard screams of pain from the learner (Figure 4).19

The Asch Studies

Another researcher, Solomon Asch, found that individuals could be influenced to say that two lines were the same length when one was clearly shorter than the other. This effect was established using groups of four or more participants who were told they were in experiments of visual perception. However, only one person in the group was actually in the experiment. The rest were confederates, and the researchers had predetermined whether or not they gave accurate answers. Groups were shown a focal line and a choice of three other lines of varying length, with one being the same length as the focal line. Most of the time the confederates would correctly state which choice matched the focal line, but occasionally they would give an obviously wrong answer. For example, looking at the following lines, the confederates might say that choice C matches the length of the focal line. When this happened, the actual research participant would go along with the wrong answer 37% of the time. When asked why they went along with the group, participants said they assumed that the rest of the group, for whatever reason, had more information regarding the correct choice. It only took three other individuals saying the wrong answer for the participant to routinely agree with the group. However, this effect was decreased by 75% if just one of the insiders gave the correct answer, even if the rest of the group gave the incorrect answer. This finding illustrates the power that even a small dissenting minority can have. Additionally, it holds even if the dissenting confederate gives a different incorrect answer. As long as one confederate gave an answer that was different from the majority, participants were more likely to give the correct answer themselves.20 A meta-analysis of 133 studies using Asch’s research design revealed two interesting patterns. First, within the United States, the level of conformity has been decreasing since the 1950s. Second, studies done in collectivistic countries such as Japan showed more conformity than those done in more individualistic countries such as Great Britain.21

Participants were asked one by one to say which of the lines on the right matched the line on the focal line on the left. While A is an exact match, many participants conformed when others unanimously chose B or C (Figure 5).

The Zimbardo Study

Philip Zimbardo, a researcher at Stanford University, conducted a famous experiment in the 1970s.22While this experiment would probably not make it past the human subjects committee of schools today, at the time, he was authorized to place an ad in the paper that asked for male volunteers to help understand prison management. After excluding any volunteers with psychological or medical problems or with any history of crime or drug abuse, he identified 24 volunteers to participate in his study. Researchers randomly assigned 18 individuals to the role of prisoner or guard. Those assigned the role of “prisoners” were surprised when they were picked up by actual police officers and then transferred to a prison that had been created in the basement of the Stanford psychology building. The guards in the experiment were told to keep order but received no training. Zimbardo was shocked with how quickly the expected roles emerged. Prisoners began to feel depressed and helpless. Guards began to be aggressive and abusive. The original experiment was scheduled to last 2 weeks, but Zimbardo ended it after only 6 days upon seeing how deeply entrenched in their roles everyone, including himself, had become. Next we will examine the relationship between dependency and power.

The Relationship Between Dependency and Power

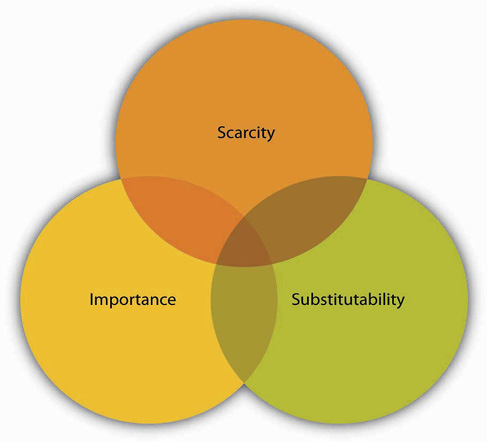

Dependency is directly related to power. The more that a person or unit is dependent on you, the more power you have. The strategic contingencies model provides a good description of how dependency works. According to the model, dependency is power that a person or unit gains from their ability to handle actual or potential problems facing the organization.23 You know how dependent you are on someone when you answer three key questions that are addressed in the following sections.

In the context of dependency, scarcity refers to the uniqueness of a resource. The more difficult something is to obtain, the more valuable it tends to be. Effective persuaders exploit this reality by making an opportunity or offer seem more attractive because it is limited or exclusive. They might convince you to take on a project because “it’s rare to get a chance to work on a new project like this,” or “You have to sign on today because if you don’t, I have to offer it to someone else.”

Importance refers to the value of the resource. The key question here is “How important is this?” If the resources or skills you control are vital to the organization, you will gain some power. The more vital the resources that you control are, the more power you will have. For example, if Kecia is the only person who knows how to fill out reimbursement forms, it is important that you are able to work with her, because getting paid back for business trips and expenses is important to most of us.

Finally, substitutability refers to one’s ability to find another option that works as well as the one offered. The question around whether something is substitutable is “How difficult would it be for me to find another way to this?” The harder it is to find a substitute, the more dependent the person becomes and the more power someone else has over them. If you are the only person who knows how to make a piece of equipment work, you will be very powerful in the organization. This is true unless another piece of equipment is brought in to serve the same function. At that point, your power would diminish. Similarly, countries with large supplies of crude oil have traditionally had power to the extent that other countries need oil to function. As the price of oil climbs, alternative energy sources such as wind, solar, and hydropower become more attractive to investors and governments. For example, in response to soaring fuel costs and environmental concerns, in 2009 Japan Airlines successfully tested a blend of aircraft fuel made from a mix of camelina, jatropha, and algae on the engine of a Boeing 747-300 aircraft (Figure 6).24

Key Takeaway

Power is the ability to influence the behavior of others to get what you want. It is often visible to others within organizations. Conformity manifests itself in several ways, and research shows that individuals will defer to a group even when they may know that what they are doing is inaccurate or unethical. Having just one person dissent helps to buffer this effect. The more dependent someone is on you, the more power you have over them. Dependency is increased when you possess something that is considered scarce, important, and nonsubstitutable by others.

The Power to Influence

Having power and using power are two different things. For example, imagine a manager who has the power to reward or punish employees. When the manager makes a request, he or she will probably be obeyed even though the manager does not actually reward the employee. The fact that the manager has the ability to give rewards and punishments will be enough for employees to follow the request. What are the sources of one’s power over others? Researchers identified six sources of power, which include legitimate, reward, coercive, expert, information, and referent.25 You might earn power from one source or all six depending on the situation.

Legitimate power is power that comes from one’s organizational role or position. For example, a boss can assign projects, a policeman can arrest a citizen, and a teacher assigns grades. Others comply with the requests these individuals make because they accept the legitimacy of the position, whether they like or agree with the request or not. Start-up organizations often have founders who use their legitimate power to influence individuals to work long hours week after week in order to help the company survive.

Reward power is the ability to grant a reward, such as an increase in pay, a perk, or an attractive job assignment. Reward power tends to accompany legitimate power and is highest when the reward is scarce. Anyone can wield reward power, however, in the form of public praise or giving someone something in exchange for their compliance. An example of reward power comes from Bill Gross, founder of Idealab, who has the power to launch new companies or not. He created his company with the idea of launching other new companies as soon as they could develop viable ideas. If members could convince him that their ideas were viable, he gave the company a maximum of $250,000 in seed money, and gave the management team and employees a 30% stake in the company and the CEO 10% of the company. That way, everyone had a stake in the company. The CEO’s salary was capped at $75,000 to maintain the sense of equity. When one of the companies, Citysearch, went public, all employees benefited from the $270 million valuation.

In contrast, coercive power is the ability to take something away or punish someone for noncompliance. Coercive power often works through fear, and it forces people to do something that ordinarily they would not choose to do. The most extreme example of coercion is government dictators who threaten physical harm for noncompliance. Parents may also use coercion such as grounding their child as punishment for noncompliance. John D. Rockefeller was ruthless when running Standard Oil Company. He not only undercut his competitors through pricing, but he used his coercive power to get railroads to refuse to transport his competitor’s products. American presidents have been known to use coercion power. President Lyndon Baines Johnson once told a White House staffer, “Just you remember this. There’s only two kinds at the White house. There’s elephants and there’s ants. And I’m the only elephant.”26

Expert power comes from knowledge and skill. We can demonstrate expert power from an ability to know what customers want — even before they can articulate it. Others who have expert power in an organization include long-time employees, such as a steelworker who knows the temperature combinations and length of time to get the best yields. Technology companies are often characterized by expert, rather than legitimate power. Many of these firms utilize a flat or matrix structure in which clear lines of legitimate power become blurred as everyone communicates with everyone else regardless of position.

Information power is similar to expert power but differs in its source. Experts tend to have a vast amount of knowledge or skill, whereas information power is distinguished by access to specific information. For example, knowing price information gives a person information power during negotiations. Within organizations, a person’s social network can either isolate them from information power or serve to create it. As we will see later in this chapter, those who are able to span boundaries and serve to connect different parts of the organizations often have a great deal of information power. In the TV show Mad Men, which is set in the 1960s, it is clear that the switchboard operators have a great deal of information power as they place all calls and are able to listen in on all the phone conversations within the advertising firm.

Referent power stems from the personal characteristics of the person such as the degree to which we like, respect, and want to be like them. Referent power is often called charisma — the ability to attract others, win their admiration, and hold them spellbound.

What Is Influence?

Starting at infancy, we all try to get others to do what we want. We learn early what works in getting us to our goals. Instead of crying and throwing a tantrum, we may figure out that smiling and using language causes everyone less stress and brings us the rewards we seek.

By the time you hit the workplace, you have had vast experience with influence techniques. You have probably picked out a few that you use most often. To be effective in a wide number of situations, however, it’s best to expand your repertoire of skills and become competent in several techniques, knowing how and when to use them as well as understanding when they are being used on you. If you watch someone who is good at influencing others, you will most probably observe that person switching tactics depending on the context. The more tactics you have at your disposal, the more likely it is that you will achieve your influence goals.

Al Gore and many others have spent years trying to influence us to think about the changes in the environment and the implications of global warming. They speak, write, network, and lobby to get others to pay attention. But Gore, for example, does not stop there. He also works to persuade us with direct, action-based suggestions such as asking everyone to switch the kind of light bulbs they use, turn off appliances when not in use, drive vehicles with better fuel economy, and even take shorter showers. Ironically, Gore has more influence now as a private citizen regarding these issues than he was able to exert as a congressman, senator, and vice president of the United States.

OB Toolbox: Self-Assessment

Do You Have the Characteristics of Powerful Influencers?

People who are considered to be skilled influencers share the following attributes.

How often do you engage in them? 0 = never, 1= sometimes, 2 = always.

- present information that can be checked for accuracy

- provide a consistent message that does not change from situation to situation

- display authority and enthusiasm (often described as charisma)

- offer something in return for compliance

- act likable

- show empathy through listening

- show you are aware of circumstances, others, and yourself

- plan ahead

If you scored 0–6: You do not engage in much effective influencing behavior. Think of ways to enhance this skill. A great place to start is to recognize the items on the list above and think about ways to enhance them for yourself.

If you scored 7–12: You engage in some influencing behavior. Consider the context of each of these influence attempts to see if you should be using more or less of it depending on your overall goals.

If you scored 13–16: You have a great deal of influence potential. Be careful that you are not manipulating others and that you are using your influence when it is important rather than just to get your own way.

Commonly Used Influence Tactics

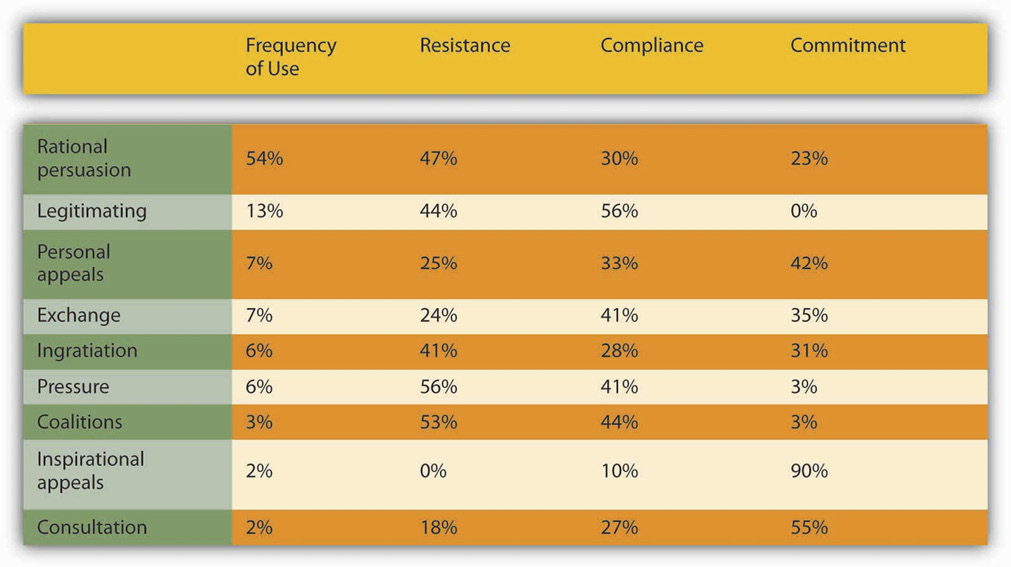

Researchers have identified distinct influence tactics and discovered that there are few differences between the way bosses, subordinates, and peers use them, which we will discuss at greater depth later on in this chapter. We will focus on nine influence tactics. Responses to influence attempts include resistance, compliance, or commitment. Resistance occurs when the influence target does not wish to comply with the request and either passively or actively repels the influence attempt. Compliance occurs when the target does not necessarily want to obey, but they do. Commitment occurs when the target not only agrees to the request but also actively supports it as well. Within organizations, commitment helps to get things done, because others can help to keep initiatives alive long after compliant changes have been made or resistance has been overcome.

- Rational persuasion includes using facts, data, and logical arguments to try to convince others that your point of view is the best alternative. This is the most commonly applied influence tactic. One experiment illustrates the power of reason. People were lined up at a copy machine and another person, after joining the line asked, “May I go to the head of the line?” Amazingly, 63% of the people in the line agreed to let the requester jump ahead. When the line jumper makes a slight change in the request by asking, “May I go to the head of the line because I have copies to make?” the number of people who agreed jumped to over 90%. The word because was the only difference. Effective rational persuasion includes the presentation of factual information that is clear and specific, relevant, and timely. Across studies summarized in a meta-analysis, rationality was related to positive work outcomes.27

- Inspirational appeals seek to tap into our values, emotions, and beliefs to gain support for a request or course of action. When President John F. Kennedy said, “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country,” he appealed to the higher selves of an entire nation. Effective inspirational appeals are authentic, personal, big-thinking, and enthusiastic.

- Consultation refers to the influence agent’s asking others for help in directly influencing or planning to influence another person or group. Consultation is most effective in organizations and cultures that value democratic decision making.

- Ingratiation refers to different forms of making others feel good about themselves. Ingratiation includes any form of flattery done either before or during the influence attempt. Research shows that ingratiation can affect individuals. For example, in a study of résumés, those résumés that were accompanied with a cover letter containing ingratiating information were rated higher than résumés without this information. Other than the cover letter accompanying them, the résumés were identical.28Effective ingratiation is honest, infrequent, and well intended.

- Personal appeal refers to helping another person because you like them and they asked for your help. We enjoy saying yes to people we know and like. A famous psychological experiment showed that in dorms, the most well-liked people were those who lived by the stairwell — they were the most often seen by others who entered and left the hallway. The repeated contact brought a level of familiarity and comfort. Therefore, personal appeals are most effective with people who know and like you.

- Exchange refers to give-and-take in which someone does something for you, and you do something for them in return. The rule of reciprocation says that “we should try to repay, in kind, what another person has provided us.”29 The application of the rule obliges us and makes us indebted to the giver. One experiment illustrates how a small initial gift can open people to a substantially larger request at a later time. One group of subjects was given a bottle of Coke. Later, all subjects were asked to buy raffle tickets. On the average, people who had been given the drink bought twice as many raffle tickets as those who had not been given the unsolicited drinks.

- Coalition tactics refer to a group of individuals working together toward a common goal to influence others. Common examples of coalitions within organizations are unions that may threaten to strike if their demands are not met. Coalitions also take advantage of peer pressure. The influencer tries to build a case by bringing in the unseen as allies to convince someone to think, feel, or do something. A well-known psychology experiment draws upon this tactic. The experimenters stare at the top of a building in the middle of a busy street. Within moments, people who were walking by in a hurry stop and also look at the top of the building, trying to figure out what the others are looking at. When the experimenters leave, the pattern continues, often for hours. This tactic is also extremely popular among advertisers and businesses that use client lists to promote their goods and services. The fact that a client bought from the company is a silent testimonial.

- Pressure refers to exerting undue influence on someone to do what you want or else something undesirable will occur. This often includes threats and frequent interactions until the target agrees. Research shows that managers with low referent power tend to use pressure tactics more frequently than those with higher referent power.30 Pressure tactics are most effective when used in a crisis situation and when they come from someone who has the other’s best interests in mind, such as getting an employee to an employee assistance program to deal with a substance abuse problem.

- Legitimating tactics occur when the appeal is based on legitimate or position power. “By the power vested in me…”: This tactic relies upon compliance with rules, laws, and regulations. It is not intended to motivate people but to align them behind a direction. Obedience to authority is filled with both positive and negative images. Position, title, knowledge, experience, and demeanor grant authority, and it is easy to see how it can be abused. If someone hides behind people’s rightful authority to assert themselves, it can seem heavy-handed and without choice. You must come across as an authority figure by the way you act, speak, and look. Think about the number of commercials with doctors, lawyers, and other professionals who look and sound the part, even if they are actors. People want to be convinced that the person is an authority worth heeding. Authority is often used as a last resort. If it does not work, you will not have much else to draw from in your goal to persuade someone.

From the Best-Seller’s List: Making OB Connections

You can make more friends in two months by becoming interested in other people than you can in two years by trying to get other people interested in you. –Dale Carnegie

How to Make Friends and Influence People was written by Dale Carnegie in 1936 and has sold millions of copies worldwide. While this book first appeared over 70 years ago, the recommendations still make a great deal of sense regarding power and influence in modern-day organizations. For example, he recommends that in order to get others to like you, you should remember six things:

- Become genuinely interested in other people.

- Smile.

- Remember that a person’s name is to that person the sweetest and most important sound in any language.

- Be a good listener. Encourage others to talk about themselves.

- Talk in terms of the other person’s interests.

- Make the other person feel important — and do it sincerely.

This book relates to power and politics in a number of important ways. Carnegie specifically deals with enhancing referent power. Referent power grows if others like, respect, and admire you. Referent power is more effective than formal power bases and is positively related to employees’ satisfaction with supervision, organizational commitment, and performance. One of the keys to these recommendations is to engage in them in a genuine manner. This can be the difference between being seen as political versus understanding politics.

Impression Management

Impression management means actively shaping the way you are perceived by others. You can do this through your choice of clothing, the avatars or photos you use to represent yourself online, the descriptions of yourself on a résumé or in an online profile, and so forth. By using impression management strategies, you control information that make others see you in the way you want to be seen. Consider when you are “being yourself” with your friends or with your family — you probably act differently around your best friend than around your mother.31 On the job, the most effective approach to impression management is to do two things at once — build credibility and maintain authenticity. As Harvard Business School Professor Laura Morgan Roberts puts it, “When you present yourself in a manner that is both true to self and valued and believed by others, impression management can yield a host of favorable outcomes for you, your team, and your organization.”32 There may be aspects of your “true self” that you choose not to disclose at work, although you would disclose them to your close friends. That kind of impression management may help to achieve group cohesiveness and meet professional expectations. But if you try to win social approval at work by being too different from your true self — contradicting your personal values — you might feel psychological distress.

It’s important to keep in mind that whether you’re actively managing your professional image or not, your coworkers are forming impressions of you. They watch your behavior and draw conclusions about the kind of person you are, whether you’ll keep your word, whether you’ll stay to finish a task, and how you’ll react in a difficult situation.

Since people are forming these theories about you no matter what, you should take charge of managing their impressions of you. To do this, ask yourself how you want to be seen. What qualities or character traits do you want to convey? Perhaps it’s a can-do attitude, an ability to mediate, an ability to make a decision, or an ability to dig into details to thoroughly understand and solve a problem.

Then, ask yourself what the professional expectations are of you and what aspects of your social identity you want to emphasize or minimize in your interactions with others. If you want to be seen as a leader, you might disclose how you organized an event. If you want to be seen as a caring person in whom people can confide, you might disclose that you’re a volunteer on a crisis helpline. You can use a variety of impression management strategies to accomplish the outcomes you want.

Here are the three main categories of strategies and examples of each:

- Nonverbal impression management includes the clothes you choose to wear and your demeanor. An example of a nonverbal signal is body art, including piercings and tattoos. While the number of people in the United States who have body art has risen from 1% in 1976 to 24% in 2006, it can hold you back at work. Vault.com did a survey and found that 58% of the managers they surveyed said they would be less likely to hire someone with visible body art, and over 75% of respondents felt body art was unprofessional. Given these numbers, it should not be surprising that 67% of employees say they conceal body art while they are at work.33

- Verbal impression management includes your tone of voice, rate of speech, what you choose to say and how you say it. We know that 38% of the comprehension of verbal communication comes from these cues. Managing how you project yourself in this way can alter the impression that others have of you. For example, if your voice has a high pitch and it is shaky, others may assume that you are nervous or unsure of yourself.

- Behavior impression management includes how you perform on the job and how you interact with others. Complimenting your boss is an example of a behavior that would indicate impression management. Other impression management behaviors include conforming, making excuses, apologizing, promoting your skills, doing favors, and making desirable associations known. Impression management has been shown to be related to higher performance ratings by increasing liking, perceived similarity, and network centrality.34

- Research shows that impression management occurs throughout the workplace. It is especially salient when it comes to job interviews and promotional contexts. Research shows that structured interviews suffer from less impression management bias than unstructured interviews, and that longer interviews lead to a lessening of the effects as well.35

Direction of Influence

The type of influence tactic used tends to vary based on the target. For example, you would probably use different influence tactics with your boss than you would with a peer or with employees working under you.

Upward influence, as its name implies, is the ability to influence your boss and others in positions higher than yours. Upward influence may include appealing to a higher authority or citing the firm’s goals as an overarching reason for others to follow your cause. Upward influence can also take the form of an alliance with a higher status person (or with the perception that there is such an alliance).36 As complexity grows, the need for this upward influence grows as well — the ability of one person at the top to know enough to make all the decisions becomes less likely. Moreover, even if someone did know enough, the sheer ability to make all the needed decisions fast enough is no longer possible. This limitation means that individuals at all levels of the organization need to be able to make and influence decisions. By helping higher-ups be more effective, employees can gain more power for themselves and their unit as well.

On the flip side, allowing yourself to be influenced by those reporting to you may build your credibility and power as a leader who listens. Then, during a time when you do need to take unilateral, decisive action, others will be more likely to give you the benefit of the doubt and follow. Both Asian American and Caucasian American managers report using different tactics with superiors than those used with their subordinates.37 Managers reported using coalitions and rationality with managers and assertiveness with subordinates. Other research establishes that subordinates’ use of rationality, assertiveness, and reciprocal exchange was related to more favorable outcomes such as promotions and raises, while self-promotion led to more negative outcomes.38 Influence takes place even before employees are hired. For example, ingratiation and rationality were used frequently by fire fighters during interviews.39 Extraverts tend to engage in a greater use of self-promotion tactics while interviewing, and research shows that extraverts are more likely to use inspirational appeal and ingratiation as influence tactics.40 Research shows that ingratiation was positively related to perceived fit with the organization and recruiters’ hiring recommendations.41

Downward influence is the ability to influence employees lower than you. This is best achieved through an inspiring vision. By articulating a clear vision, you help people see the end goal and move toward it. You often don’t need to specify exactly what needs to be done to get there — people will be able to figure it out on their own. An inspiring vision builds buy-in and gets people moving in the same direction. Research conducted within large savings banks shows that managers can learn to be more effective at influence attempts. The experimental group of managers received a feedback report and went through a workshop to help them become more effective in their influence attempts. The control group of managers received no feedback on their prior influence attempts. When subordinates were asked 3 months later to evaluate potential changes in their managers’ behavior, the experimental group had much higher ratings of the appropriate use of influence.42 Research also shows that the better the quality of the relationship between the subordinate and their supervisor, the more positively resistance to influence attempts are seen.43 In other words, bosses who like their employees are less likely to interpret resistance as a problem.

Peer influence occurs all the time. But, to be effective within organizations, peers need to be willing to influence each other without being destructively competitive.44 There are times to support each other and times to challenge — the end goal is to create better decisions and results for the organization and to hold each other accountable. Executives spend a great deal of their time working to influence other executives to support their initiatives. Research shows that across all functional groups of executives, finance or human resources as an example, rational persuasion is the most frequently used influence tactic.45

OB Toolbox: Getting Comfortable With Power

Now that you’ve learned a great deal about power and influence within organizations, consider asking yourself how comfortable you are with the three statements below:

- Are you comfortable saying, “I want to be powerful” to yourself? Why or why not?

- Are you comfortable saying, “I want to be powerful” to someone else? Why or why not?

- Are you comfortable having someone say, “You are powerful” to you? Why or why not?

Discomfort with power reduces your power. Experts know that leaders need to feel comfortable with power. Those who feel uncomfortable with power send those signals out unconsciously. If you feel uncomfortable with power, consider putting the statement in a shared positive light by saying, “I want to be powerful so that we can accomplish this goal.”

Key Takeaway

Individuals have six potential sources of power, including legitimate, reward, coercive, expert, information, and referent power. Influence tactics are the way that individuals attempt to influence one another in organizations. Rational persuasion is the most frequently used influence tactic, although it is frequently met with resistance. Inspirational appeals result in commitment 90% of the time, but the tactic is utilized only 2% of the time. The other tactics include legitimizing, personal appeals, exchanges, ingratiation, pressure, forming coalitions, and consultation. Impression management behaviors include conforming, making excuses, apologizing, promoting your skills, doing favors, and making associations with desirable others known. Influence attempts may be upward, downward, or lateral in nature.

Exercises

- Which of the six bases of power do you usually draw upon? Which do you use the least of at this time?

- Distinguish between coercive and reward power.

- Which tactics seem to be the most effective? Explain your answer.

- Why do you think rational persuasion is the most frequently utilized influence tactic?

- Give an example of someone you’ve tried to influence lately. Was it an upward, downward, or lateral influence attempt?

References

1. Leung, A. S. M. (2008). Matching ethical work climate to in-role and extra-role behaviors in a collectivist work-setting. Journal of Business Ethics, 79, 43–55; Mulki, J. P., Jaramillo, F., & Locander, W. B. (2006). Effects of ethical climate and supervisory trust on salesperson’s job attitudes and intentions to quit. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 26, 19–26; Valentine, S., Greller, M. M., & Richtermeyer, S. B. (2006). Employee job response as a function of ethical context and perceived organization support. Journal of Business Research, 59, 582–588.

2. Somers, M. J., & Casal, J. C. (1994). Organizational commitment and whistle-blowing: A test of the reformer and the organization man hypotheses. Group & Organization Management, 19, 270–284.

3. Crossen, B. R. (1993). Managing employee unethical behavior without invading individual privacy. Journal of Business and Psychology, 8, 227–243.

4. Weinstein, B. (2007, October 15). If it’s ethical, it’s legal, right? Businessweek, accessed February 24, 2012, http://www.businessweek.com/managing/content/oct2007/ca20071011_458606.htm

5. Brown, M. (2010). Ethics in organizations. Santa Clara University, accessed June 2, 2012, http://www.scu.edu/ethics/publications/iie/v2n1/

6. Sims, R. R. (1991). Journal of Business Ethics, 10(7), 493–506

7. Rao Rama, V. S. (2009, April 17). Four levels of ethics. Citeman Network, accessed February 24, 2012, http://www.citeman.com/5358-four-levels-of-ethical-questions-in-business.html

8. Jacobson, M. (2010, June 22). McDonald’s lawsuit: Using toys to sell Happy Meals, accessed February 24, 2012, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/michael-f-jacobson/mcdonalds-lawsuit-manipul_b_621503.html

9. The Associated Press. (2012, April 5). Calif. judge dismisses suit against McDonald’s toys. USA Today, accessed June 4, 2012, http://www.usatoday.com/money/industries/food/story/2012-04-05/mcdonalds-happy-meals-toys-lawsuit/54040390/1

10. New York Times. (n.d.). Bribe study singles out 3 countries, accessed June 4, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/04/business/worldbusiness/04iht-bribes.3031969.html?_r=1

11. Durando, J. (2010, June 1). BP’s Tony Hayward: I’d like my life back, USA Today, accessed June 3, 2012, http://content.usatoday.com/communities/greenhouse/post/2010/06/bp-tony-hayward-apology/1

12. Outpatient Surgery. (n.d.). Whistle blowing surgeon awarded $900,000, accessed February 24, 2012, http://www.outpatientsurgery.net/news/2012/02/32-Whistleblowing-Surgeon-Awarded-900-000

13. Sarbanes Oxley Act, 2002, section 806.

14. Nash, L. (1981). Ethics without the sermon. Howard Business Review, 59 79–90, accessed February 24, 2012, http://www.cs.bgsu.edu/maner/heuristics/1981Nash.htm

15. Corey, G., Corey, M . S., & Callanan, P. (1998). Issues and ethics in the helping professions. Toronto: Brooks/Cole Publishing Company; Syracuse School of Education. (n.d.). An ethical decision making model, accessed February 24, 2012, http://soe.syr.edu/academic/counseling_and_human_services/modules/Common_Ethical_Issues/ethical_decision_making_model.aspx

16. Salancik, G., & Pfeffer, J. (1989). Who gets power. In M. Thushman, C. O’Reily, & D. Nadler (Eds.), Management of organizations. New York: Harper & Row.

17. Kidder, T. (2004). Mountains beyond mountains: The quest of Dr. Paul Farmer, a man who would cure the world. New York: Random House; Mortenson, G., & Relin, D. O. (2006). Three cups of tea: One man’s mission to promote peace…One school at a time. New York: Viking.

18. CNN.com. (2005, January 15). Graner sentenced to 10 years for abuses. Retrieved November 4, 2008, from http://www.cnn.com/2005/LAW/01/15/graner. court.martial/.

19. Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority. New York: Harper & Row.

20. Asch, S. E. (1952b). Social psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; Asch, S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological Monographs, 70(9), Whole No. 416.

21. Bond, R., & Smith, P. B. (1996). Culture and conformity: A meta-analysis of studies using Asch’s (1952b, 1956) line judgment task. Psychological Bulletin, 119, 111–137.

22. Zimbardo, P. G. Stanford prison experiment. Retrieved January 30, 2009, from http://www.prisonexp.org/.

23. Saunders, C. (1990, January). The strategic contingencies theory of power: Multiple perspectives. Journal of Management Studies, 21(1), 1–18.

24. Krauss, C. (2009, January 30). Japan Airlines joins the biofuels race. New York Times. Retrieved January 30, 2009, from http://greeninc.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/01/30/japan-airlines-joins-the-biofuels-race/.

25. French, J. P. R., Jr., & Raven, B. (1960). The bases of social power. In D. Cartwright & A. Zander (Eds.), Group dynamics (pp. 607–623). New York: Harper and Row.

26. Hughes, R., Ginnet, R., & Curphy, G. (1995). Power, influence and influence tactics. In J. T. Wren (Ed.), The leaders companion (p. 345). New York: Free Press.

27. Higgins, C. A., Judge, T. A., & Ferris, G. R. (2003). Influence tactics and work outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 89–106.

28. Varma, A., Toh, S. M., & Pichler, S. (2006). Ingratiation in job applications: Impact on selection decisions. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21, 200–210.

29. Cialdini, R. (2000). Influence: Science and practice. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, p. 20.

30. Yukl, G., Kim, H., & Falbe, C. M. (1996). Antecedents of influence outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 309–317.

31. Dunn, E., & Forrin, N. (2005).Impression management. Retrieved July 8, 2008, from http://www.psych.ubc.ca/~dunnlab/publications/Dunn_Forrin_2005.pdf.

32. Stark, M. (2005, June 20). Creating a positive professional image. Q&A with Laura Morgan Roberts. Retrieved July 8, 2008, from the Harvard Business School Web site: http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/4860.html.

33. Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology Inc. (SIOP). (2008, February 6). Body art on the rise but not so trendy at work. Retrieved February 8, 2008, from the SIOP Web site: http://www.siop.org.

34. Barsness, Z. I., Diekmann, K. A., & Seidel, M. L. (2005). Motivation and opportunity: The role of remote work, demographic dissimilarity, and social network centrality in impression management. Academy of Management Journal, 48, 401–419; Wayne, S. J., & Liden, R. C. (1995). Effects of impression management on performance ratings: A longitudinal study. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 232–260.

35. Tsai, W., Chen, C., & Chiu, S. (2005). Exploring boundaries of the effects of applicant impression management tactics in job interviews. Journal of Management, 31, 108–125.

36. Farmer, S. M., & Maslyn, J. M. (1999). Why are styles of upward influence neglected? Making the case for a configurational approach to influences. Journal of Management, 25, 653–682; Farmer, S. M., Maslyn, J. M., Fedor, D. B., & Goodman, J. S. (1997). Putting upward influence strategies in context. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 18, 17–42.

37. Xin, K. R., & Tsui, A. S. (1996). Different folks for different folks? Influence tactics by Asian-American and Caucasian-American managers. Leadership Quarterly, 7, 109–132.

38. Orpen, C. (1996). The effects of ingratiation and self promotion tactics on employee career success. Social Behavior and Personality,24, 213–214; Wayne, S. J., Liden, R. C., Graf, I. K., & Ferris, G. R. (1997). The role of upward influence tactics in human resource decisions. Personnel Psychology, 50, 979–1006.

39. McFarland, L. A., Ryan, A. M., & Kriska, S. D. (2002). Field study investigation of applicant use of influence tactics in a selection interview. Journal of Psychology, 136, 383–398.

40. Cable, D. M., & Judge, T. A. (2003). Managers’ upward influence tactic strategies: The role of manager personality and supervisor leadership style. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 197–214; Kristof-Brown, A., Barrick, M. R., & Franke, M. (2002). Applicant impression management: Dispositional influences and consequences for recruiter perceptions of fit and similarity. Journal of Management, 53, 925–954.

41. Higgins, C. A., & Judge, T. A. (2004). The effect of applicant influence tactics on recruiter perceptions of fit and hiring recommendations: A field study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 622–632.

42. Seifer, C. F., Yukl, G., & McDonald, R. A. (2003). Effects of multisource feedback and a feedback facilitator on the influence behavior of managers toward subordinates. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 561–569.

43. Tepper, B. J., Uhl-Bien, M., Kohut, G. F., Rogelberg, S. G., Lockhart, D. E., & Ensley, M. D. (2006). Subordinates’ resistance and managers’ evaluations of subordinates’ performance. Journal of Management, 32, 185–208.

44. Cohen, A., & Bradford, D. (2002). Power and influence in the 21st century. In S. Chowdhurt (Ed.), Organizations of the 21st century. London: Financial Times-Prentice Hall.

45. Enns, H. G., & McFarlin, D. B. (2003). When executives influence peers: Does function matter? Human Resource Management, 42, 125–142.