Rhetoric

Rhetoric

The term rhetoric has come to take several different and incompatible meanings—some of them rather negative and unfortunate—but in the context of college writing we use its original meaning, which, according to Aristotle, is “the art of finding all available means of persuasion.” Aristotle meant persuasion through words, not through physical confrontation. So as it applies to writing, a rhetorical choice is any choice the author makes to be more persuasive in expressing ideas.

This, by the way, is the real meaning of rhetorical question: a question that’s not a true inquisition looking for an answer, but instead a point phrased as a question to help clarify a message.

So rhetorical strategies are any writing strategies authors use to best convey their ideas to their readers, or convince readers to agree, or be as clear and inviting as possible to the minds of their readers.

Rhetoric can also take the broader meaning of using the audience or readers as your guide for making writing decisions. This is another approach to some of the basic principles at the very beginning of this textbook: that you should consider your audience as you write. In this way, all efforts toward clarity and correctness in order to convey your ideas can be labeled as rhetoric.

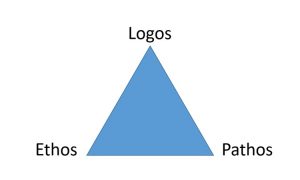

Three Rhetorical Appeals

In his classic handbook Rhetoric (quoted above), Aristotle noted that there are three main appeals in persuasion. These three rhetorical appeals are still relevant today and have widespread use in modern writing. They are the following:

Appeals to logos: the mode of persuasion through logic, reason, rationality. This often relies on critical thinking, careful explanation, and facts.

Appeals to ethos: the mode of persuasion through relying on credibility, trustworthiness, reputation, or some type of common authority. This means persuasion relying not so much on what is said (as per logos) but instead on who says it. This often involves using quotations from legitimate institutions, admired or credentialed personalities, or respected books. Due diligence by the writer is also an appeal to ethos, for readers are more likely to listen to someone who writes and cites correctly than they are to writers who are sloppy or careless.

Appeals to pathos: the mode of persuasion through emotion or audience-reactions. Such emotions could be outrage, nostalgia, pride, pity, defensiveness, even curiosity or humor. This often relies on audience bias, consensus opinion, attitude, and gut-feeling. Writers sometimes appeal to ethos by choosing stark examples, provocative images, and loaded word-choices.

Examples of the Three Rhetorical Appeals

The following are brief excerpts from Abraham Lincoln’s first inaugural address, which appeal to logos, ethos, and pathos respectively.

Appeal to logos:

In the above excerpt, Lincoln attempts to explain rationally why his audience, who are his opponents, should take their time in deciding to act. This is an appeal to logos because he explains the two conditions–hasty action and deliberate action–and the consequences of each in the mode of a logical argument. He also happens to be encouraging logical thinking in his audience, which makes this a kind of double appeal.

Appeal to ethos:

In the above excerpt, Lincoln attempts to establish his own position as one who cannot be the aggressor in the conflict at hand, but also as one who will have no choice but to act in defense if others choose to be the aggressors. This is an appeal to ethos because it tries to show why he should be listened to, explaining why he is not the revolutionary that his enemies fear that he will be, and why his position is not a choice–as his opponents’ position is–but a duty.

Appeal to pathos:

This final paragraph of Lincoln’s first inaugural address evokes such uplifting imagery that we continue to reference it in the famous phrase “the better angels of our nature.” In this excerpt, Lincoln attempts to connect to the transcendent in the heart of his audience and is thus one of our culture’s finest examples of the appeal to pathos.

Other Common Rhetorical Strategies

Ancient and older schools used to teach 26 different rhetorical strategies (that they referred to more technically as topics), but this is a lot for modern students to memorize and practice. And many rhetoricians have created lists much longer than this, enumerating rhetorical strategies and techniques into the hundreds. In the 1950s, a group of professors from the University of Chicago came up with an idea to make these strategies more manageable and useful; they combined all 26 into 4 basic strategies. They referred to them using the following terms:

- Genus

- Consequence

- Likeness and Difference

- Testimony and Authority

This isn’t the only way to look at rhetorical strategy, and it isn’t the one right way, but it can be useful. Here, I have used this University of Chicago approach, but I have made a couple of alterations: (1) I have added the strategy of illustration, and (2) I have made some changes to the names:

- Illustration

- Definition

- Consequence

- Comparison

- Testimony

Illustration is the strategy of offering specific examples or instances in a persuasive way. This can help make abstract ideas more concrete for readers, helping them to see your ideas more clearly. Instances that you invent or fictionalize are often called illustrations, and instances you reference that are real are often called examples, but the terms are interchangeable. Narratives often function as illustrations as well. If you claim that school uniforms censor students’ thoughts and opinions unfairly, and to make your claim clearer you describe instances of students getting in trouble for wearing “Black Lives Matter” shirts, then you are using the rhetorical strategy of illustration.

Definition is the strategy of using key words or phrases in a persuasive way. It is helpful to think of this strategy as re-defining words in the author’s own way. This is also the strategy of placing ideas into categories. If you say the death penalty is murder, or that it is justice, you are attempting to define the death penalty and are therefore using the rhetorical strategy of definition.

Consequence is the strategy of explaining causes or effects in a persuasive way. Writers often try to explain why things have happened (causes) or what will be the outcome of something (effect), or even how events are related. An example of the use of consequence: “Video games do not make children violent. Instead, children who are already violent tend to play violent video games.”

Comparison is the strategy of showing how things are similar or how they are different in a persuasive way. Note that comparison includes contrasting, as when you compare prices to find differences in them. A common form of comparison is an analogy. As an example, you could say that using multiple-choice tests in English class is as silly as testing by playing “pin the tail on the donkey”: students can succeed at both by blindly guessing. This would be an argument that uses the rhetorical strategy of comparison.

Testimony is the strategy of referencing or quoting others in a persuasive way. Any time a writer brings in outside material, such as statistics, cases or precedents, news stories, laws, or similar material, that writer is using the rhetorical strategy of testimony. It is often persuasive to bring in quotations and ideas from experts, historical figures, or highly respected persons, such as Martin Luther King, Jr., because such uses of testimony have instant credibility—which makes them simultaneously appeals to ethos (described above). To use research in essays, as we do in this class, is to use the rhetorical strategy of testimony.

Other Perspectives on Rhetorical Strategies

There are many other valid ways to conceive of rhetorical strategies, and many other ways to analyze an author’s rhetorical strategies.

For instance, imagine an article that tries to define abortion as murder by citing the Bible. If you were to analyze that rhetorical strategy, you could call it an appeal to ethos (the authority of the Bible), or an appeal to pathos (drumming up emotions or biases), or the use of definition, or the use of testimony. All these different types of analysis are valid, so there are many possible right answers. What matters most is what the analysis says about how that strategy is put to use.

Further, the above types of rhetorical strategies are merely the classic or common types, but you could find perfectly valid rhetorical strategies that are not mentioned here, and you could use your own perfectly valid terms for them.

Examples of Rhetorical Strategies

What follows is another excerpt from Henry David Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience,” and then a brief analysis of examples from that address that fit the strategies noted above.

After all, the practical reason why, when the power is once in the hands of the people, a majority are permitted, and for a long period continue, to rule is not because they are most likely to be in the right, nor because this seems fairest to the minority, but because they are physically the strongest. But a government in which the majority rule in all cases can not be based on justice, even as far as men understand it. Can there not be a government in which the majorities do not virtually decide right and wrong, but conscience?–in which majorities decide only those questions to which the rule of expediency is applicable? Must the citizen ever for a moment, or in the least degree, resign his conscience to the legislator? Why has every man a conscience then? I think that we should be men first, and subjects afterward. It is not desirable to cultivate a respect for the law, so much as for the right. The only obligation which I have a right to assume is to do at any time what I think right. It is truly enough said that a corporation has no conscience; but a corporation on conscientious men is a corporation with a conscience. Law never made men a whit more just; and, by means of their respect for it, even the well-disposed are daily made the agents on injustice. A common and natural result of an undue respect for the law is, that you may see a file of soldiers, colonel, captain, corporal, privates, powder-monkeys, and all, marching in admirable order over hill and dale to the wars, against their wills, ay, against their common sense and consciences, which makes it very steep marching indeed, and produces a palpitation of the heart. They have no doubt that it is a damnable business in which they are concerned; they are all peaceably inclined. Now, what are they? Men at all? or small movable forts and magazines, at the service of some unscrupulous man in power? Visit the Navy Yard, and behold a marine, such a man as an American government can make, or such as it can make a man with its black arts–a mere shadow and reminiscence of humanity, a man laid out alive and standing, and already, as one may say, buried under arms with funeral accompaniment, though it may be,

“Not a drum was heard, not a funeral note,

As his corse to the rampart we hurried;

Not a soldier discharged his farewell shot

O’er the grave where out hero was buried.”

Illustration:

This is illustration because Thoreau gets specific in creating an image of a file of various military men.

Definition:

This is definition because Thoreau tries to recategorize these military men.

Consequence:

This is consequence because Thoreau attempt to identify the cause of majority rule.

Comparison:

This is comparison because Thoreau tries to contrast a state run by mere majority against a state run by conscience.

Testimony:

Visit the Navy Yard, and behold a marine, such a man as an American government can make, or such as it can make a man with its black arts–a mere shadow and reminiscence of humanity, a man laid out alive and standing, and already, as one may say, buried under arms with funeral accompaniment, though it may be,

“Not a drum was heard, not a funeral note,

As his corse to the rampart we hurried;

Not a soldier discharged his farewell shot

O’er the grave where out hero was buried.”

This is testimony because Thoreau quotes the poem “The Burial of Sir John Moore” by Charles Wolfe.

Exercise 1

Read either “An Animal’s Place” by Michael Pollan, “The Moral Equivalent of War” by William James, or “The Federalist No. 10” by James Madison, and analyze its three rhetorical appeals:

- Logos

- Pathos

- Ethos

And analyze its rhetorical strategies:

- Illustration

- Definition

- Consequence

- Comparison

- Testimony