Comparison and Contrast

The primary aim of comparing and contrasting in college writing is to clarify meaningful, non-obvious features of similarity and difference. In this case, comparison means showing similarity or likeness, and contrasting means showing difference or distinction. Comparing and contrasting is a vital skill in writing and critical thinking, and even essays that are not explicitly “compare-and-contrast” assignments require this skill as a means to clarify and sharpen your ideas.

Indeed, this skill was traditionally valued and lauded as the intellectual qualities of wit and judgment: wit being the ability to see creative connections between things that normally seem quite different, and judgment being the ability to draw important distinctions between things that normally seem quite similar. For example, wit would be intelligent explication of how the journeys of Moses and Odysseus follow the same important steps–that would be a strong use of comparison. And, for example, judgment would be an intelligent clarification of why inequality is essentially different from poverty, and why public policy should focus on the latter–that would be a strong use of contrast.

There is no real point in explaining obvious or insignificant similarities and differences, of course, nor is there much of a point in comparing two similar subjects, or contrasting two different subjects. But this is where students most struggle with comparison and contrast: identifying obvious features or features that provide no real insight into their subjects.

For example, it would be a failure of thought and writing skill to spend time contrasting horror movies and romantic comedies by pointing out that horror movies typically involve more terror and violence than the love and hijinks of a romantic comedy. The two kinds of films are already different, so contrasting them in such a way adds no real insight. And it would be an equal failure to compare horror movies and romantic comedies by pointing out that they are both genres of cinema and that involved directors, producers, and actors. Although those would be similar features between different things, they are obvious similarities, so they fail to show meaningful connections.

Why do student writers so often fail in such ways? One reason is that listing the obvious is a quicker and simpler activity than real comparison and contrast, which is rigorous and requires both imaginative and critical thought. Another reason is the fear of being wrong, or of being informed that you are wrong, which is ever-present when venturing a new insight or creative idea. You can avoid being wrong by stating only the obvious and superficial, but the result of such safety is the failure to compare and contrast, thereby defeating the purpose. Instead, you must risk being wrong by seeking unique and significant connections and distinctions. And then you can do your best to use the writing process stages of revision and editing to clean out the bad ideas and sharpen the good ones. Regardless of the result, the mere act of going through this risk and process further conditions your imaginative and critical thinking, and further hones your writing skills.

Exercise 1

The ideas below are often considered synonyms, but careful contrasting can illuminate important distinctions between them. Select one pair, and use only your own thoughts and words to contrast them. Try offering an example, and seek to explain the contrast in two to five sentences.

- Leisure and idleness

- Sports and athletics

- Consistency and uniformity

Exercise 2

The ideas below are often considered extremely different, but careful comparison can illuminate important similarities and connections between them. Select one pair, and use only your own thoughts and words to compare them. Try offering an example, and seek to explain the comparison in two to five sentences.

- Work and play

- Holidays and warfare

- Parenting and video gaming

Categories and Criteria

Comparison and contrast often work by engaging in classification, which means explaining how your subjects can actually fit a different type of category than readers would typically realize, or how your subjects should not be placed in their typically assumed categories. Although classification is often treated as a different type of writing assignment, it is often a version of comparison and contrast–or comparison and contrast are versions of classification.

For example, writers such as Sarah Jilek and Michael Wilmington have published essays in which they assert that the Christmas classic It’s a Wonderful Life is essentially film noir, a genre which would otherwise seem like the opposite of Christmas movies. This is the use of categories, taking a subject from one category and placing it in a new category, but this classification works by drawing comparisons between the style, theme, and structure of this Christmas movie and those same qualities of film noir.

Or your could take two subjects and classify them together in the same category through comparison, such as arguing that the films Home Alone and Die Hard are both essentially horror movies. That would require drawing comparisons between both examples films–family and action genres, respectively–and the films that typically fit the horror genre. Or you could argue that Home Alone is essentially a type of Die Hard movie, which would mean treating the latter as a kind of category of its own.

All of this can also be done through the lens of contrast. For example, Home Alone is generally regarded as an example of the fun-loving family genre, but you could argue that the movie is actually inappropriate for children. That would involve contrasting what is featured as comical in Home Alone–violence, child abandonment, home invasion, vigilantism–with the category of family films, shedding light on important distinctions between the two.

Related to this use of categories is the use of criteria. Criteria are standards or qualities that candidates must meet or include. For example, criteria for a passing essay might including (1) a minimum of 2,500 words, (2) the use of MLA format, and (3) the citation of at least seven sources. Failing to meet one criterion of these three, such as the minimum word count, would mean that the candidate essay does not fit the category of a passing essay, and it would thus fail.

Criteria can help sharpen and clarify your thinking about categories, and about how your subjects compare to and contrast with them, and with each other. You can establish criteria in your essay, explain what they are and why, and then you can apply your subjects to those criteria as candidates to see how they compare and contrast. Using the above examples for instance, you could determine five features that a Christmas movie must have, and then you could walk Home Alone through each of them to see if or how well it meets all five, and then you could walk Die Hard through each of them and see if or how well it meets all five. This would be comparing and contrasting through the use of criteria.

There are many advantages to using criteria, such as the organization and expansiveness they lend automatically to essays, but this approach does add the extra stage of establishing the criteria, and that often requires rigorous critical thinking in order to come up with criteria that truly work. For example, a student might find it natural to say that the criteria of a “ball sport” are that (1) it must involve two opposing players or teams, (2) it must be competitive, determining a winner through scored points, and (3) the guided movement of the ball must score those points. These three criteria would allow basketball, football, soccer, and tennis to fit the category of “ball sport,” but baseball would fail to meet the third criterion: in baseball, points are scored by the player reaching home, not the ball. So the student who established this criteria would have to apply critical thinking to notice this discrepancy, and then do the work to go back in and revise the criteria–or perhaps make the argument that baseball is not a ball sport, which would be a kind of contrast essay.

Again, finding a new or unique category for a subject, and making that re-classification make worthwhile sense, requires both creative and critical thinking. Such are the rigors and aims of comparison and contrast.

Exercise 3

Using your own ideas and words, try explaining one of the following options in a paragraph. This involves using a category to make comparisons.

- Casual small talk as a type of workforce skill

- Water as a type of drug

- Science as a type of religion

- Dating as a type of art

- Art as a type of dating

Exercise 4

Select one of the following options, and develop three to five criteria for it. Then apply two different candidate examples to each of the criteria, explaining briefly if or how well they meet the criteria. Use your own ideas and words for this exercise.

- Board games

- Holidays

- Violence

- Literature

Conclusions and Judgments

One difficulty of comparison and contrast is that a worthwhile conclusion can sometimes seem evasive. Even if you can point out significant similarities or differences between your subjects, you might not have addressed the natural question, “So what?” What does it matter that your two similar subjects are significantly different? Or that your two different subjects are significantly similar?

Especially for essays focused on contrast, this difficulty can be addressed by seeking a conclusion of judgment. That means determining which of your contrasting subjects is better, a kind of “this versus that” essay. If, for example, you were contrasting two different film versions of Hamlet, you could drive all of your points of contrast toward a conclusion of which version was better. The most careful and organized way to level such as judgment in an essay is to use criteria, as noted above.

For essays focused on comparison, this kind of judgment can work by elevating one of the compared subjects. In other words, you might compare two subjects, such as Hamlet and The Lion King, in order to conclude that The Lion King should be taken more seriously as literature. This would be comparison using a kind of judgment as a conclusion or ultimate point: that the lesser Disney story is similar to the greater Shakespeare story, thus elevating the lesser. And the use of criteria helps here too, as does the use of categories.

There are other types of conclusions available as well, but you must be mindful of the need to include some ultimate point or answer to, “So what?” An essay that shows its readers significant similarities and/or differences must also so them why that matters.

Organization

The compare-and-contrast essay often starts with a thesis that clearly states the subjects that are to be compared, contrasted, or both, as well as the reason for doing so. The thesis could lean more toward comparing, or contrasting, or it could focus on both equally. Remember that the point of comparing and contrasting is to provide insight to the reader. Take the following thesis as an example that leans more toward contrasting.

Here the thesis sets up the two subjects to be compared and contrasted (organic versus conventional vegetables), and it makes a claim about the results that might prove useful to the reader.

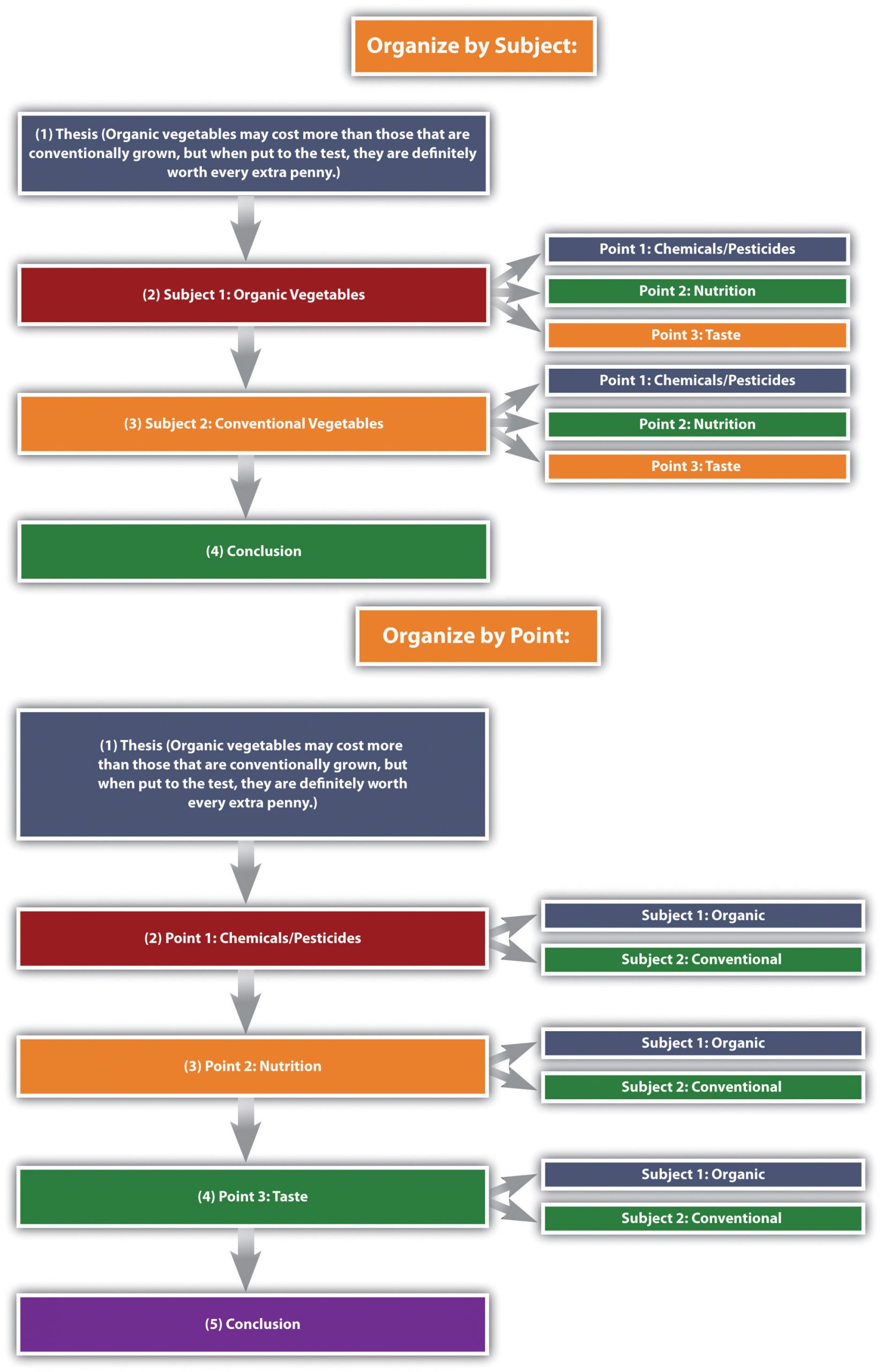

The standard compare-and-contrast essays could be organized in one of the following two ways:

- According to the subjects themselves, discussing one then the other

- According to individual points, discussing each subject in relation to each point

The figures below diagram the two different types of typical organization, using the example of organic versus conventional vegetables.

These two types of organization apply to most types of compare-and-contrast essays, even those involving categories and criteria, which often use the second organizational strategy (organizing by points). But there are far too many possibilities and variations to say that these are the only two types of organization. Ultimately, you must make your organizational decisions based on your subject, your purpose, and your audience.

Example

See the following essay as an example of comparing and contrasting in which the writer, Wes O’Donnell, takes two concepts that are so similar as to be considered synonyms in some cases, and then clarifies the vital distinction we should make between them, all the while providing insight through context and origin. The primary focus here is on contrasting two similar subjects, but the essay takes time to establish at least one important and non-obvious way the two are similar. Finally, this essay addresses the difficulty of concluding a compare/contrast essay by establishing a meaningful judgment–which of the two similar ideas is better–and clarifying why.

Patriotism vs. Nationalism- What’s the Difference?

by Wes O’Donnell

Published in Medium

Aug 29, 2019

America is wholly unique among the nations of the world. Conceived as an asylum for oppressed peoples everywhere, George Washington would write, “I had always hoped that this land might become a safe and agreeable asylum to the virtuous and persecuted part of mankind, to whatever nation they might belong.”

America enjoys influence from everywhere:

France helped secure our independence. Our numbers come from India and Baghdad. Our religions are from Palestine, Saudi Arabia, and Israel. Our languages have mostly Latin and Asian roots. Our arts are from Greece. Our jurisprudence comes from Rome. Our 4th of July fireworks were invented in China. Our calendar comes from the Catholic Church. I hail from Germany and Ireland. My neighbors are from Mexico and Africa. I served in the American military with men and women who came from all points on the compass.

As Jill Lepore says, “To love this particular nation… is to love the world.”

Patriotism and Nationalism: Two Very Different Things

Rarely in the history of the United States have two words that are so contradictory today, been used so interchangeably in the past.

In fact, patriotism is the older of the two words, dating back to the mid-17th century. Its first use was recorded in 1653:

“There is hardly any judicious man but knoweth, that it was neither learning, piety, nor patriotism that perswaded any of that Nation to Presbytery….” (C.N., Reasons Why the Supreme Authority of the Three Nations (for the time) is not in the Parliament, 1653)

The word nationalism came along a full 150 years later and until the 20th century was used interchangeably with Patriotism to mean roughly the same thing.

It wasn’t until World War II that the word nationalism began to take on a negative connotation. It was used frequently in media of the day to describe the fervent German expansion of the 1930s.

Today, Merriam-Webster treats nationalism and patriotism as synonyms; however, they acknowledge that the pair are problematic and while the definition of patriotism has remained unchanged through the years, the word nationalism has grown apart.

So Where Do the Words Stand Today?

The challenge that we face is that there is no consensus, even among scholars and social scientists, where to draw a line between the pair of words.

A quote by Sydney J. Harris best sums up the current outlook on the pair:

“The difference between patriotism and nationalism is that the patriot is proud of his country for what it does, and the nationalist is proud of his country no matter what it does.”

A nationalist believes that his country is the best because they live in it. But a patriot believes that his country is the best but there is always room for improvement.

A nationalist can’t tolerate any criticism of his country and considers it an insult. But a patriot can tolerate criticism and have a thoughtful conversation about improvements.

A nationalist puts more importance on unity through a shared cultural background. But a patriot puts more importance on unity through shared values.

Many even go so far as to define nationalism as evil, xenophobic and racist.

Is Nationalism All Bad?

Surprisingly, no. Nationalism has its uses as a very strong motivator for uniting people together in the struggle against injustice.

As an example, recall the 20th-century anti-colonialism struggles in Africa and India driven by a strong nationalist sentiment among the oppressed peoples.

Some political analysts feel that peace in the Middle East can only be achieved through a strong national identity of the countries involved, as opposed to the current tribal and religious identities that divide them. Embracing national identities over religious may make it easier to negotiate through national amendable laws rather than ambiguous religious laws.

But in a country like America, there is a very strong connection between nationalism and extremism. Putting America first ahead of our enemies is fine. But putting America first over our allies creates a much more unstable Europe and Asia, as long-standing trade and defense agreements crumble under the weight of our own self-interest.

If the evil “globalist agenda” is spending a little more foreign aid now to avoid war, health or humanitarian crises at a future date, then call me a globalist.

It’s okay to feel like your country is exceptional. I believe in American exceptionalism, but not because I had the good fortune of being born here. Instead, I believe that America is exceptional because of our shared values and our willingness to help other countries experience the same freedom.

As for nationalism, America’s strong national identity has always manifested itself in the form of patriotism. As a nation made up of bits and pieces of cultures from all over the world, American nationalism shouldn’t exist. In this country, we have no shared ethnic heritage. Writings from our country’s founders show men who envisioned a land made up of oppressed peoples from all nations on Earth.

Patriotism and our shared values might just be the path out of the venomous divisiveness that we find ourselves in now. Emphasizing what we’re about, rather than who we are, is always a good bet for Americans.

I’m always at my proudest when I stand with patriots.