Illustration

Illustration in writing is the use of words to show, represent, or demonstrate an idea, point, or concept by using examples, images, or vivid clarifying information. In other words, illustration means to shed light on something, which is what the word’s etymology indicates: illustration is from the Latin lustrare, “to shine light on.”

It’s worth noting that another common meaning associated with the word illustration is a literal picture, as in a purely visual image without words, but that is not the meaning of illustration in writing as we use it here. When such pictures are discussed in or added to college essays, they are typically called figures.

You might notice that illustration and narrative writing are quite similar in many ways, for they both seek to render abstract ideas more concretely for readers. In fact, for college writing purposes, it’s fair to consider narration a special type of illustration. But there are still means of engaging in illustration that do not require the telling of a full story, as narrative does. Illustration writing can include full stories, but it can also consist of a series of examples and instances, or even just one example. The instances used in illustration can be imagined or factual or anywhere in-between; they can be equally effective once they become clear in the reader’s mind.

Since it’s so versatile, illustration can be used as an entire mode of writing–such as a full illustration essay–or as a single strategy within an essay, or even within a paragraph.

Illustration is particularly powerful for effective communication with readers. Much like narrative, it gives readers a way to visualize your ideas or points, which makes them seem more real. It is so common in communication that it might be considered the most natural type of support for a claim. If you want someone to understand what you mean, you need to give them an example, and if you don’t, they are likely to ask, “What do you mean?” Which is another way of saying to give an example, to use illustration. Every example of masterful writing in the Readings in this textbook use illustration. Every college textbook you have uses illustration. Every one of your professor’s lectures includes illustration. Yet students so often fail to use it in their own writing. Why? Perhaps because they are so busy getting a handle on the many new abstractions and theories that college classes present that they forget to make those ideas real, concrete, and specific with illustrations. More often, this failure comes from the erroneous or default assumptions that readers always know exactly what a writer means or intends without the use of words. But readers can’t every really know what you mean in a clear, specific way until you illustrate it.

And when you employ illustration in your essays, you will often want to prepare readers for them with brief phrases that help in the transition from abstract to specific, such as the following:

Phrases of Illustration

| case in point | for example |

| for instance | in particular |

| in this case | one example/another example |

| specifically

e.g. |

to illustrate

imagine this: |

Illustration for Support

The primary use of illustration in college writing is to support a claim. This is how it can be used as a minor strategy within an argumentation, analysis, or similar essay, or as an entire mode of writing itself: a pure illustration essay assignment essentially asks you to support claims primarily through illustration. Typically, you have two options for engaging in such illustration essay assignments: (1) to use narrative as your illustration, or (2) to provide a series of logically relevant examples as your illustration. Illustration as support is thus quite versatile, and it can range in tone and use from the calm and meticulous, to provoking and emotional, as seen in the following examples.

For a calm and meticulous use of illustration for support, consider the following claim that Jacques Barzun makes about the use of multiple-choice testing in schools in his essay “Reasons to De-Test the Schools”:

He has provided a key term for his critique of multiple-choice testing: “recognition knowledge.” And he has explained what recognition knowledge is and why it is an inferior type of knowledge to test. Despite this information, most of us will still be left wondering, “What do you mean?” We don’t yet have a clear concept of what recognition knowledge would look like beyond just a theory. Barzun, a masterful writer, anticipates this and moves immediately into an illustration of recognition knowledge.

[The use of multiple-choice in schools] tests nothing but recognition knowledge. This is knowledge at the far side of the memory, where shapes are dim. Take a practical situation. A friend plans to drive to a town where you spent a month several years ago. Can you help him with some precise indications? Well, you remember a few landmarks—city hall, big church on main street, post office on one of the side roads. Your knowledge, distressingly vague, stops there.

Yet if you join him and drive through that main street, it all comes back—things look familiar, including the names of shops and streets; you even notice changes. But—and this is the point— you did not know until you saw. You are glad to find that your memory is not a sieve, but when it was called on to perform without the renewed experience it was useless. It had only passive recognition-knowledge, not active usable-knowledge.

–Jacques Barzun, “Reasons to De-Test the Schools”

Notice that the author describes a specific scenario that shows how recognition knowledge works, and even why it fails as an unusable, passive form of knowledge. He provides clear images to help us see why multiple-choice testing both relies on and encourages this inferior type of knowledge: friends discussing directions, driving through a city, watching particular landmarks and streets, etc. Barzun’s illustration here is clearly imagined or made-up for the purposes of clarifying, and it is no less effective for that. We now have a much clearer understanding of what he means and are more likely to find his critiques about his subject valid.

Immediately after the above excerpt, Barzun goes on to further clarify how this applies directly to schools and testing:

The application to schoolwork is obvious. Knowing something—really knowing it—means being able to summon it up out of the blue; the facts must be produced in their right relations and with their correct significance. When you know something, you can tell it to somebody else. It is these profound platitudes that condemn mechanical testing and its influence on the learning mind.

Again, this is highly competent explanation, and we might understand it in theory, but it has not yet become real in the mind because we don’t have a specific example to anchor the theory onto. What kinds of questions do this in such tests? Would we be able to see the difference between these two levels of testing? We don’t yet get answers. So, again, Barzun makes the effective writing decision to offer illustration. The very next sentences in that paragraph are as follows:

Imagine the two different actions: it is one thing to pick out Valley Forge and not Albany or Little Rock as the place where Washington made his winter quarters; it is another, first, to think of Valley Forge and then to say why he chose it instead of Philadelphia, where it was warmer. (The pivotal fact here is that Philadelphia was in the hands of the British.)

This provides a specific illustration of two types of questions that could confront students: an inferior multiple-choice question, and a superior question of real knowledge. In this case, the illustration is somewhere between imagined and real, but that matters little. What matters most is that his ideas have now become concrete and thereby more effective.

For a provoking and emotional use of illustration as support, see the following example from “Letter from Birmingham Jail” by Martin Luther King, Jr. It is a masterful example of illustration in combination with appeal to ethos. Among the many brilliant writing choices in this paragraph, watch for the specific instances that show you exactly what it looks like to suffer while others tell you calmly to “wait.”

We have waited for more than 340 years for our constitutional and God-given rights. The nations of Asia and Africa are moving with jetlike speed toward gaining political independence, but we stiff creep at horse-and-buggy pace toward gaining a cup of coffee at a lunch counter. Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging dark of segregation to say, “Wait.” But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate-filled policemen curse, kick and even kill your black brothers and sisters; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society; when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six-year-old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky, and see her beginning to distort her personality by developing an unconscious bitterness toward white people; when you have to concoct an answer for a five-year-old son who is asking: “Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?”; when you take a cross-country drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you; when you are humiliated day in and day out by nagging signs reading “white” and “colored”; when your first name becomes “nigger,” your middle name becomes “boy” (however old you are) and your last name becomes “John,” and your wife and mother are never given the respected title “Mrs.”; when you are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tiptoe stance, never quite knowing what to expect next, and are plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you go forever fighting a degenerating sense of “nobodiness” then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait. There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men are no longer willing to be plunged into the abyss of despair. I hope, sirs, you can understand our legitimate and unavoidable impatience.

–Martin Luther King, Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail”

Exercise 1

Using any one of the Readings in this textbook as assigned by your instructor, identify a claim the reading makes and then the illustration it uses as support.

Illustration for Introductions

As explained and shown in the section Paragraph Basics, good introductions often begin in medias res, jumping right into something specific and interesting within your subject, and one of the best ways to achieve this is by illustration. You can begin by showing your reader a curious or compelling instance of engaging with your subject matter, and then you can follow that up with clarifying explanations leading to your thesis and main point

The following example is the first paragraph in Michael Pollan’s essay “An Animal’s Place,” which you can find in its entirety in the chapter Readings. After this use of illustration, he immediately explains the subject and context of his inquiry, and eventually reveals his ultimate thesis, but here he offers readers a glimpse into his dilemma in medias res:

The Key to Illustration: Specificity

Illustration works through specificity, which means using words that render particular images and instances. Students often have difficulty achieving this in their writing because it requires an acute combination of critical thinking, awareness of audience, and creative thinking. In order to be specific, you have to figure out what the important pieces of your subject are, and which the audience needs to be shown in order to understand, and finally how to imagine something precise enough to convey in detail.

But this difficulty is not insurmountable. Two models for improving your understanding and use of specificity are the Ladder of Abstraction and the Five Senses. More information and exercises are provided in the section Specificity, but the useful models and examples are also provided here.

The Ladder of Abstraction

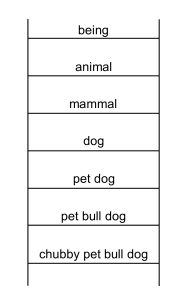

One useful model of thought to aid in specificity is the Ladder of Abstraction, proposed by S.I. Hayakawa in his book Language in Thought and Action. It is a way of visualizing a type of idea as a vertical ladder, and visualizing the different words for the idea as rungs on that ladder. The higher the rung, the more that word is abstract, general, or vague. The lower the rung, the more that word is specific, particular, or detailed. Example:

Words that are high in abstraction are open to interpretation but lack guidance about which interpretation the writer means. Words low in abstraction–more specific words–present more precise images or ideas. It is important to realize that your readers can always move up the Ladder of Abstraction, but they cannot move down. This means that if you give them the specific phrase “my chubby pet bull dog,” reader can also understand that you’re conveying the idea of a pet, a dog, a mammal, or a being in general. But if you were to give them the mildly abstract word “dog,” or the more abstract word “mammal,” reader can never be expected to correctly interpret your meaning of “chubby pet bull dog.” So in order to more clearly convey your ideas, you need to get specific.

The Five Senses

Another model of thought to aid in specificity is an ancient one: Aristotle’s model of the human being as having five senses. They are commonly identified as sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell.

Describing an example that employs the use of these senses is a way to be specific. Or another way of looking at it is this: if what you are describing can be filmed, listened to, or touched, it is likely to be specific. If it can’t be, then it’s not. This often helps writers who confuse their own abstract expressions with the more specific images they have in mind but haven’t yet articulated.

For example, many students identify the word “happiness” as specific. But can you see “happiness”? Can it be filmed? This is often where students refer to a “smile,” but that was not the word in question. “Smile” is specific; it can be seen, filmed, etc. But “happiness” is not; it is abstract. You cannot see happiness, or hear it, or touch it, taste it, or smell it. You could only use those senses for more specific instances of happiness, such as smiling, laughter, an so on.

Exercise 2

Offer specific illustrations of the following abstractions:

- Luck

- Daydreaming

- The joy of coming home

- The fear of change

- Failing but continuing to try

Illustrating Aphorisms

Because illustration is so vital to effective articulate expression, it has been used in assignments since at least the schooldays of the Roman Empire, and one such common assignment has been illustrating aphorisms, or short statements of general or universal truth. The following is an example of a famous aphorism:

“That which does not destroy us makes us stronger.”

—Nietzsche

This aphorism carries a lot of significant meaning, and because it is a general or universal truth, it is applicable to many situations. But the exact way you interpret and understand it–or the length to which you do–is not yet clear, for this statement remains necessarily abstract, or vague. In order to show that you can and do understand it, and in order to show exactly how you do or how it applies to your mindset, you would need to illustrate it.

This assignment requires you to develop the skill of illustration along with all the important abilities associated with it: critical thinking, awareness of audience, and creative thinking. Thus, it is an ancient, relevant, and important writing challenge.

There are typically two approaches to illustrating aphorisms, as noted above under Illustration as Support: (1) use narrative as your illustration, or (2) provide a series of logically relevant examples as your illustration.

Exercise 3

Using the above concepts, illustrate one of the following aphorisms in one paragraph:

- No great man ever complains of want of opportunity. (Emerson)

- Beware of telling an improbable truth. (Dr. Fuller)

- When we are in love, we often doubt what we most believe. (La Rochefoucauld)

- The wise man does once what the fool does finally. (Gracian)

- Who lies for you will lie against you. (Bosnian Proverb)

- The ears are the last feature to age. (Chazal)

- Honesty is often in the wrong. (Lucan)

- What was hard to endure is sweet to recall. (Continental Proverb)

The above are quoted from the following book: Auden, W.H., and Louis Kronenberger. The Viking Book of Aphorisms. Viking, 1962.

Further Examples of Illustration

To see masterful example of illustrating an aphorism, consider the aphorism, “Human suffering has become a spectator sport.” Then read “The Perfect Picture” by James Alexander Thom. This essay is also a masterful example of illustration writing in general (regardless of the aphorism).

As another masterful example of illustrating an aphorism, consider the aphorism, “Knowledge is power.” Then read Chapters VI and VII of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass.

For a student example of illustration, read and evaluate the following:

America’s Pastime

As the sun hits my face and I breathe in the fresh air, I temporarily forget that I am at a sporting event. But when I open my eyes and look around, I am reminded of all things American. From the national anthem to the international players on the field, all the sights and sounds of a baseball game come together like a slice of Americana pie.

First, the entrance turnstiles click and clank, and then a hallway of noise bombards me. All the fans voices coalesce in a chorus of sound, rising to a humming clamor. The occasional, “Programs, get your programs, here!” jumps out through the hum to get my attention. I navigate my way through the crowded walkways of the stadium, moving to the right of some people, to the left of others, and I eventually find the section number where my seat is located. As I approach my seat I hear the announcer’s voice echo around the ball park, “Attention fans. In honor of our country, please remove your caps for the singing of the national anthem.” His deep voice echoes around each angle of the park, and every word is heard again and again. The crowd sings and hums “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and I feel a surprising amount of national pride through the voices. I take my seat as the umpire shouts, “Play ball!” and the game begins.

In the fifth inning of the game, I decide to find a concessions stand. Few tastes are as American as hot dogs and soda pop, and they cannot be missed at a ball game. The smell of hot dogs carries through the park, down every aisle, and inside every concourse. They are always as unhealthy as possible, dripping in grease, while the buns are soft and always too small for the dog. The best way to wash down the Ball Park Frank is with a large soda pop, so I order both. Doing my best to balance the cold pop in one hand and the wrapped-up dog in the other, I find the nearest condiments stand to load up my hot dog. A dollop of bright green relish and chopped onions, along with two squirts of the ketchup and mustard complete the dog. As I continue the balancing act between the loaded hot dog and pop back to my seat, a cheering fan bumps into my pop hand. The pop splashes out of the cup and all over my shirt, leaving me drenched. I make direct eye contact with the man who bumped into me and he looks me in the eye, looks at my shirt, tells me how sorry he is, and then I just shake my head and keep walking. “It’s all just part of the experience,” I tell myself.

Before I am able to get back to my seat, I hear the crack of a bat, followed by an uproar from the crowd. Everyone is standing, clapping, and cheering. I missed a home run. I find my aisle and ask everyone to excuse me as I slip past them to my seat. “Excuse me. Excuse me. Thank you. Thank you. Sorry,” is all I can say as I inch past each fan. Halfway to my seat I can hear discarded peanut shells crunch beneath my feet, and each step is marked with a pronounced crunch.

When I finally get to my seat I realize it is the start of the seventh inning stretch. I quickly eat my hot dog and wash it down with what is left of my soda pop. The organ starts playing and everyone begins to sing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” While singing the song, putting my arms around friends and family with me, I watch all the players taking the field. It is wonderful to see the overwhelming amount of players on one team from around the world: Japan, the Dominican Republic, the United States, Canada, and Venezuela. I cannot help but feel a bit of national pride at this realization. Seeing the international representation on the field reminds me of the ways that Americans, though from many different backgrounds and places, still come together under common ideals. For these reasons and for the whole experience in general, going to a Major League Baseball game is the perfect way to glimpse a slice of Americana.

Exercise 4

Identify the thesis, main claim, or aphorism the above student example attempts to illustrate. Then evaluate its use of illustration, particularly its ability to create clear examples and images through specificity. Where does it succeed, and where does it fail? Which parts are strongest, and which are weakest? Why?