14 Early Cultures and Civilizations in the Americas

Around 3000 BCE, after millennia of thriving as hunter-gatherers, Indigenous peoples in the Americas began to develop complex societies centered on agriculture. This marked a significant shift, as communities transitioned from nomadic lifestyles to settled villages, and eventually, to large, architecturally sophisticated cities. From the Andean region to the Eastern Woodlands of North America, these societies flourished, giving rise to distinctive regional cultures.

It’s essential to acknowledge that this process was not uniform and was shaped by the diverse experiences and traditions of Native peoples. The development of agriculture was a gradual process, with various communities adopting and adapting farming practices at different times and in different ways. Additionally, the impact of agriculture on social structures, spiritual beliefs, and artistic expression varied across regions.

As settled communities grew, they developed unique cultural practices, including art, architecture, religion, and pottery design, which reflected their distinct histories, environments, and worldviews. These regional similarities and differences are a testament to the creativity, resilience, and diversity of Native American cultures.

Complex Civilizations in Mesoamerica

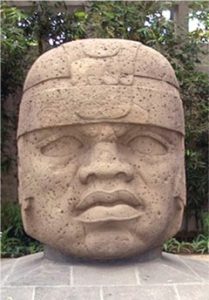

By 1200 BCE, agriculture had firmly established itself in southern Mexico, particularly in the Gulf lowlands where irrigation systems supported the cultivation of crops. This period marked the rise of the Olmec civilization, one of the earliest known complex societies in Mesoamerica. The Olmecs developed significant urban centers, with San Lorenzo (in modern-day Veracruz, Mexico) being a prominent example. The site featured a massive earthen platform that supported ceremonial structures, water reservoirs, and the famous colossal stone heads. These heads, some weighing up to 50 tons, were meticulously carved from volcanic basalt and transported from quarries many miles away, showcasing the Olmec’s advanced engineering and organizational skills.

The Olmec civilization was marked by its sophisticated cultural and social structures. It boasted a defined elite class and monumental architecture that reflected their complex societal organization. Their art and iconography reveal a rich pantheon of gods and supernatural beings, suggesting a deep spiritual and ritualistic life. The Olmec engaged in a ritual ball game, believed to be a significant religious and ceremonial activity used to communicate with the spirit world and reinforce social hierarchies. These cultural elements, combined with their architectural innovations, underscore the Olmec’s role in shaping early Mesoamerican civilization.

By around 900 BCE, La Venta (in modern-day Tabasco, Mexico) had emerged as the dominant city in the region. La Venta’s urban design represented a significant advancement in Mesoamerican architecture and city planning. The city’s layout included temples and ceremonial complexes arranged on a north-south axis, symbolically linking rulers with supernatural forces and aligning with cosmic principles. This sophisticated urban planning reflected the Olmec’s evolving understanding of space and spirituality, influencing the development of later Mesoamerican urban centers.

Despite its decline around 400 BCE, the Olmec civilization left a lasting legacy on subsequent Mesoamerican cultures. The Maya, among others, inherited various aspects of Olmec culture, including ritual practices, artistic styles, and calendrical systems. The continuity of certain religious symbols and social structures suggests that the Olmec civilization had a profound and enduring impact on the cultural and historical development of Mesoamerica. This influence highlights the Olmec’s foundational role in shaping the trajectory of Mesoamerican civilization.

Overall, the Olmec civilization represents a crucial phase in the development of early complex societies in the Americas. Their achievements in agriculture, urban planning, and cultural expression set the stage for the rise of subsequent civilizations across Mesoamerica. The Olmec’s contributions to architecture, art, and religion not only defined their own era but also provided a rich heritage that influenced the region’s future cultural and societal evolution.

The Zapotec civilization emerged in the Oaxaca Valley of western Mexico around 500 BCE, with Monte Albán serving as its regional capital on a strategically advantageous flattened mountaintop. By 400 BCE, the city’s population was about 5,000, growing to around 25,000 by 700 CE as it expanded with impressive stone temples and complex structures. The fertile soil of the region, ideal for maize cultivation, supported this growth. Monte Albán’s defensive walls suggest a history of conflict, but the city was also a significant cultural and economic center, with extensive trade networks and elaborate temples. After 300 CE, architectural styles at Monte Albán began reflecting influences from Teotihuacán, highlighting the complex interactions between Mesoamerican civilizations.

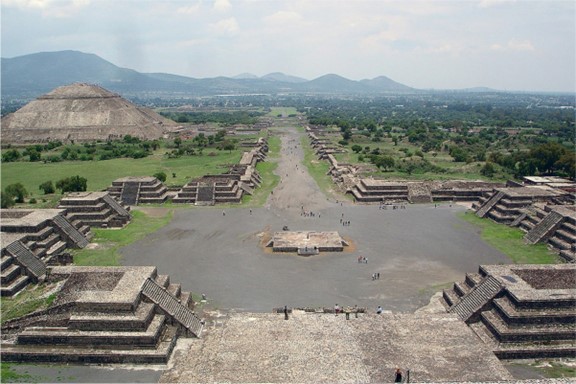

Teotihuacán (teh-oh-tee-wah-KAHN), situated in the Basin of Mexico, emerged as a dominant urban center around 200 BCE, eventually becoming one of the largest cities in the ancient world by 100 CE. With a population estimated between 100,000 and 200,000, the city showcased a remarkable example of urban planning, featuring monumental architecture like the Pyramid of the Sun and the Pyramid of the Moon. Teotihuacán’s strategic location and impressive infrastructure enabled it to develop extensive trade networks, connecting it with other Mesoamerican civilizations and solidifying its position as a major political and economic hub. The city’s influence extended far beyond its borders, shaping cultural and architectural developments throughout the region. As a result, Teotihuacán became a model for subsequent civilizations, demonstrating the power of organized urban planning and monumental architecture.

Teotihuacán reached its zenith between 300 and 600 CE, marked by significant expansion and the construction of iconic structures like the Citadel and the Avenue of the Dead, a grand ceremonial route lined with temples and palaces. The city’s population swelled, and its influence spread across Mesoamerica through both direct and indirect means, including trade, cultural exchange, and artistic diffusion. Teotihuacán’s art and architectural styles had a profound impact on subsequent cultures, such as the Maya and Zapotecs, who adopted and adapted elements of its complex cosmology and urban design. Despite its decline around 650 CE, likely due to internal conflicts and external pressures, Teotihuacán’s legacy continued to resonate throughout Mesoamerican history, leaving an indelible mark on the region’s cultural and architectural heritage. The city’s influence can still be seen in the many civilizations that followed, a testament to its enduring impact on Mesoamerican society.

The Maya civilization was influenced by the Teotihuacanos starting in the fourth century CE, but evidence of urban development and rapid population growth in the Maya heartland of Central America dates back to before 600 BCE. By 600 BCE, the lowlands of Central America were dotted with small villages, each showcasing sophisticated pottery, architecture, irrigation techniques, and religious traditions. By 250 BCE, a handful of powerful Maya city-states had emerged, including Tikal, Calakmul, El Mirador, and others. These cities featured impressive pyramid-like structures, and most were built near large, shallow lakes to ensure access to water for drinking and irrigation.

The Maya developed a style of slash-and-burn agriculture to raise crops like maize, squash, beans, and cacao for their growing urban populations. They were also influenced by the Olmec civilization, as seen in their art, ritual ball game, and calendar system. The Maya calendar consisted of two parts: the 260-day Sacred Round calendar and the 365-day Vague Year calendar, which functioned together to create a 52-year cycle for measuring time and tying dates to important mythological events. The Classic period of Maya civilization began around 250 CE and lasted until about 900 CE, during which time urbanization expanded greatly, with approximately forty different city-states emerging.

At the heart of Maya religious practices was the veneration of family ancestors, who were considered bridges between heaven and earth. Homes had shrines for performing ritual bloodletting and prayers directed to the ancestors, and deceased family members were typically interred beneath the floor. The large stone temples themselves were grander versions of these family shrines, usually with large tombs within them. Ritual practices were tied to the complicated Maya calendar, and gods could act in certain ways depending on the time of year and the location of heavenly bodies. Shamans and priests guided rituals like bloodletting, which allowed for communication with the ancestors.

The Maya writing system, unlike others in Mesoamerica, has been decoded and read by scholars. This phonetically based system allowed the Maya to record their history in stone monuments, including political histories, descriptions of rituals, and genealogies. Classical Maya civilization entered a period of decline in the ninth century CE and then deteriorated rapidly, with alliances breaking down, conflicts increasing, and cities becoming depopulated. The reason for this collapse is still debated among historians and archaeologists, with proposed causes including epidemic diseases, invasions, natural disasters, internal revolutions, and environmental degradation.

Core Impact Skill — Perspective-Taking

Understanding the Maya world requires more than memorizing dates and monuments—it asks us to see through the eyes of a people whose relationship to time, family, and the cosmos shaped every aspect of life. For the Maya, time was not linear but cyclical, guided by sacred calendars that connected the movements of the heavens with earthly rituals. Ancestors were not gone but present—interred beneath homes, honored in daily life, and invoked through sacred bloodletting. Temples were not just places of worship but monumental family altars, linking generations to the divine.

Perspective-taking helps us move beyond modern assumptions about religion, politics, and science. Instead of viewing the Maya calendar as primitive or superstitious, we can appreciate it as a precise tool for marking time and orchestrating ritual life. Rather than judging bloodletting rituals as violent, we can see them as acts of reverence meant to maintain cosmic balance and ancestral ties.

-

🌀 What does the Maya calendar reveal about how they understood time, nature, and divine action?

-

🏛 How does honoring ancestors in Maya daily life challenge our modern view of religion as something separate from home and family?

Studying the Maya through their own lens helps us confront our biases, respect different ways of knowing, and better understand how cultural practices give meaning to life across time and place.

Early Cultures and Civilizations in South America

The dense tropical jungle, stretching south of Mesoamerica and north of the Andes, historically hindered regular communication and cultural exchange between these regions. This geographical barrier led to the independent development of early cultures and civilizations in South America, each adapting to its unique environmental challenges. Around 3000 BCE, Neolithic settlers began establishing complex communities in the coastal and highland regions of present-day Peru. Notable early sites included Norte Chico, known for its advanced urban planning, and religious and ceremonial centers such as Huaricoto, Galgada, and Kotosh in the Northern Highlands. The builders of Sechin Alto, located along the desert coast, constructed their site after 2000 BCE, while ceremonial structures around Lake Titicaca, dating to around 1000 BCE, indicate the development of sophisticated ritual practices.

By 900 BCE, the Chavín culture began to dominate the Andes, marking the beginning of the Early Horizon or Formative period. Chavín artisans created a distinctive style of pottery, featuring fluid depictions of people, deities, and animals, which spread across the region. The central religious site of Chavín de Huántar, with its extensive temple complex and intricate maze of tunnels, became a focal point of Chavín influence. The prominent sculpture of El Lanzón, blending human and animal forms, exemplifies the culture’s rich spiritual symbolism.

Link to Learning

Explore artifacts (https://openstax.org/l/77Artifacts) from the Chavín at the Metropolitan Museum of Art website.

Despite the decline of Chavín influence around 200 BCE, its cultural and religious impact persisted across the Andes. New societies emerged, developing advanced textile production and metalworking techniques, and expanding trade networks utilizing llamas as pack animals. The fragmentation of the Chavín-era unity led to the rise of distinct civilizations such as the Moche, Nazca, and Tiwanaku. The Moche civilization, based in northern Peru, is known for its monumental pyramid structures and intricate administrative systems. Moche society was highly militaristic, as evidenced by their art. Meanwhile, the Nazca, living in smaller villages, are renowned for their ceremonial site Cahuachi and the creation of the Nazca Lines—large geoglyphs etched into the desert floor.

The Tiwanaku civilization, centered around Lake Titicaca, thrived with impressive stone architecture and carved artworks, including enigmatic “trophy heads.” At its zenith, Tiwanaku supported a substantial population and exerted influence over surrounding regions. The civilization declined around 1000 CE, potentially due to rising water levels in Lake Titicaca. The Moche and Nazca civilizations faced decline between 500 and 600 CE, likely linked to environmental changes. Successive Andean civilizations, such as the Wari and Chimor, built on earlier achievements, with Chimor enduring until its conquest by the Inca in the 15th century.

Early Civilizations and Cultures in North America

The earliest complex societies in North America, known to us through archaeological records, began to emerge in the Ohio River valley around 1000 BCE, marking the onset of the Formative period. During this time, mound-building cultures with sizable populations became more prevalent in the Eastern Woodlands, signaling a significant shift towards increased social complexity. These early societies, although not yet fully urbanized, laid the groundwork for the development of more intricate social hierarchies and specialized labor systems.

The Adena culture, named after a mound excavated in Ohio in 1901, was a mound-building society that emerged in the Ohio River valley around 1000 BCE. These mounds, numbering in the hundreds, served as burial sites for important individuals, often decorated with red ocher and accompanied by grave objects like jewelry, weapons, and pipes. Over time, the mounds grew in size as more people were buried and additional earth was added, sometimes surrounded by circular ditches and logs.

The Adena culture eventually gave rise to the Hopewell tradition, which emerged around 200 BCE and spread across the Eastern Woodlands through a network of trade routes. The Hopewell culture is notable for its impressive earthwork complexes, such as the one in Ohio that spans 130 acres and features thirty-eight mounds within a large earthen rectangle. These mounds were used for ceremonial purposes, and their construction required significant labor and organization. The Hopewell people lived in small, dispersed communities, employing a mix of hunter-gatherer strategies and domesticated plant cultivation.

The Hopewell culture was highly organized, with ceremonial sites used for religious events and ancestor veneration. These sites, such as the one near Newark, Ohio, feature earthen enclosures, mounds, and observation circles aligned with lunar movements, likely used to predict eclipses and seasonal events. The items deposited in the mounds, including artistic depictions of animals and supernatural mixtures, held symbolic importance for individual kin groups and were connected to religious practices and ancestral ceremonies.

The Hopewell tradition was decentralized and egalitarian, with no powerful rulers but rather a leadership structure revolving around shamans or shamanistic practices. Specialization and division of labor existed, including healers, clan leaders, and spiritual interpreters. Ceremonial objects made of copper, bone, stone, and wood aided shamanistic figures in their duties and were often buried with them. Extensive long-distance trading is also evident, with items like copper from Lake Superior and obsidian from the Rocky Mountains discovered in the Ohio River valley.

In the northeastern regions of present-day United States and Canada, Indigenous cultures flourished with a deep connection to the diverse environments they inhabited. By 500 CE, societies in this area had developed intricate systems for living in the dense forests and abundant waterways. Groups such as the Iroquois and Algonquin established complex agricultural practices, including the cultivation of the “Three Sisters,” which formed the cornerstone of their diet. This practice improved soil fertility through complementary planting techniques. The abundant resources supported a rich cultural life, with intricate pottery, woven textiles, and elaborate ceremonial practices reflecting a profound spiritual connection to the natural world.

Settlements ranged from small, seasonal camps to more permanent villages with sophisticated wooden structures and communal spaces. The Iroquois Confederacy established a series of longhouses arranged in a village layout that facilitated social and political organization. Indigenous peoples in this region also engaged in extensive trade networks that spanned vast distances, exchanging goods like copper, shells, and fur. These networks helped to disseminate cultural practices and technologies, contributing to the region’s dynamic and interconnected societies.

In the vast Great Plains, Indigenous peoples developed a rich cultural tradition deeply connected to the land and its resources. From around 3000 BCE, these communities relied on a diverse range of animals and plants, with bison playing a central role in their way of life. They employed sophisticated hunting practices, utilizing various tools and techniques to manage their interactions with these large herds. Over time, they refined their methods and developed intricate social structures and spiritual practices centered around the bison.

In the arid Southwest, a unique cultural tradition developed, distinct from the mound-building cultures in the East. Early settlers began experimenting with maize cultivation around 3000 BCE, planting small plots along riverbanks to complement their hunter-gatherer lifestyle. According to Native American perspectives, maize, often considered a sacred gift from the Earth and divine beings, has deep spiritual significance and was integral to their way of life from its earliest cultivation. Evidence confirms that maize was introduced from southern Mexico, with frequent contact between cultivators and hunter-gatherers facilitating this exchange. The region’s dry conditions initially limited maize farming, making it a smaller part of their lifestyle.

By 2250 BCE, maize farming became more established in northwestern New Mexico. By 1200 BCE, communities in the Las Capas area near present-day Tucson, Arizona, had developed advanced irrigation systems, constructing canals to direct water from the Santa Cruz River to their fields. They built oval-shaped homes and roasting pits for maize, with these structures arranged around central courtyards. Around 500 BCE, beans were introduced alongside maize in a method known as the “Three Sisters.” This technique, cherished in Native traditions, involves planting maize, beans, and squash together: maize provides support for the beans, beans enrich the soil with nitrogen, and squash shades the ground to help retain moisture and suppress weeds. Despite these advancements, maize cultivation was just one part of a broader hunter-gatherer lifestyle that included gathering wild plants and hunting.

It wasn’t until around 200 CE that settled agricultural communities began to take shape, marking a significant transition towards more permanent living arrangements and the emergence of complex societies such as the Ancestral Puebloans, also known as the Anasazi. This gradual shift from experimental maize cultivation to established agricultural practices reflected not just technological advancement but also a profound relationship with the land, viewed by Native cultures as a source of life and spirituality. The evolution of maize farming was thus intertwined with the cultural and spiritual fabric of the region, laying the groundwork for sophisticated societies in the Southwest.

In present-day California, Indigenous cultures developed a diverse array of sophisticated societies long before European contact. By 500 CE, California was home to numerous Nat ions, each with unique cultural practices adapted to their specific environments. The region’s varied landscapes supported an abundance of resources, which Indigenous peoples utilized to cultivate a wide range of plants, including acorns, and harvest rich marine life. They developed complex social structures, built sturdy homes, and created intricate art and ceremonial objects. Trade networks extended across the region, connecting different communities and facilitating the exchange of goods.

Cultural practices in California were deeply tied to the environment, with Indigenous peoples employing innovative techniques to manage and utilize resources effectively. For example, the Chumash constructed plank-built canoes for ocean travel, while the Pomo created elaborate basketry. The complexity of their societies is evident in their sophisticated craftsmanship, social hierarchies, and ceremonial traditions. By 500 CE, these diverse cultures had developed rich traditions and a profound connection to their lands, reflecting their adaptability and resilience.

In the Pacific Northwest, a unique cultural tradition developed, shaped by the region’s rich natural resources and diverse environments. From around 3000 BCE, Indigenous peoples focused on utilizing the abundant marine life and forest resources available to them. Salmon, a central element in their diet and spirituality, were revered and seen as a sacred gift from the spirits. The Coast Salish and Haida, among others, built large wooden homes from cedar and created intricate totem poles that depicted their spiritual beliefs and social structures. A key cultural practice, the potlatch, served as a ceremonial gathering where leaders distributed wealth to demonstrate their status and reinforce social ties. These events involved feasting, storytelling, and the exchange of gifts, highlighting the community’s interconnectedness and shared values. Their reliance on fishing, along with seasonal migrations and trade networks, allowed them to thrive in this resource-rich environment.

By 500 BCE, these societies had refined their technologies and social systems to enhance their sustainable practices. They constructed sophisticated fish weirs and tools that improved their fishing efficiency while maintaining harmony with their environment. The deep understanding of the natural cycles enabled them to manage resources responsibly, ensuring the health and continuity of their ecosystems. The development of these technologies and practices reflects the profound connection they had with their land and its offerings, demonstrating a sophisticated balance between their cultural practices and environmental stewardship.