32 Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome’s history began in 753 BCE when legendary twin brothers Romulus and Remus founded the city, though archaeological evidence indicates that various Italic tribes inhabited the site earlier. The Roman Kingdom (753-509 BCE) was ruled by seven kings, including Romulus, Numa Pompilius, and Tarquinius Superbus, during which Rome established its initial infrastructure, laws, and social hierarchy. The monarchy ended in 509 BCE when Tarquinius Superbus was overthrown, leading to the establishment of the Roman Republic. This new government emerged from the struggle against monarchical rule and aimed to create a representative system, with the Senate, comprised of patrician families, and the Assemblies representing the plebeians. Early in the Republic, conflicts between these classes and external threats from neighboring cities arose, but Rome expanded its territories through a series of wars, setting the stage for its rise as a dominant Mediterranean power. Influential figures such as Lucius Junius Brutus, Publius Valerius Poplicola, and Horatius Cocles were instrumental in shaping the Republic’s institutions and values, which would leave a lasting legacy on Western politics, law, and culture.

This sixteenth-century engraving illustrates the legend that the infants Romulus and Remus were suckled by a she-wolf after a jealous king ordered them abandoned to die. (attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

This sixteenth-century engraving illustrates the legend that the infants Romulus and Remus were suckled by a she-wolf after a jealous king ordered them abandoned to die. (attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

The Roman Republic

In the early republic, Rome was ruled by elected magistrates instead of kings, and by a Council of Elders or Senate. Roman society was divided into two classes or orders, patricians and plebeians. The patricians were the aristocratic elite, who alone could hold public office and sit in the Senate. From the beginning of the republic through the third century BCE, the plebeians, or common people, worked to achieve equality before the law in Roman society. The political conflict between these two classes is known as the Struggle of the Orders. In 450 BCE, the plebeians went on strike for the first time. They feared that patrician judges were interpreting Rome’s unwritten laws to take advantage of ignorant plebeians, so they demanded the laws be written down. The patricians agreed. In the Twelve Tables, published in the Forum, Rome’s laws were written for the first time and were then accessible to all citizens.

Link to Learning

Read excerpts from Rome’s Twelve Tables of law (https://openstax.org/l/77TwelveTables) from Fordham University’s Ancient History Sourcebook. What do these laws tell us about Roman society in 450 BCE, when they were first written down?

The Roman Republic was a complex system of governance that heavily relied on tradition and the “way of the ancestors,” known as *mos maiorum*. This conservative framework combined established customs with written laws that evolved since the Republic’s inception. By the third century BCE, the administration of the Republic was divided among public assemblies, elected officials, and the Senate. The three main public assemblies—the Plebeian Assembly, Tribal Assembly, and Centuriate Assembly—played crucial roles in electing officials and shaping the Republic’s laws.

The Plebeian Assembly, which was exclusive to plebeians, elected ten tribunes annually, who were granted veto power and lawmaking abilities to protect the interests of the common people. The Tribal Assembly, open to both plebeians and patricians, elected Quaestors to manage public finances and handle administrative tasks. In contrast, the Centuriate Assembly, which had the authority to declare war, was organized into wealth-based blocs that disproportionately favored affluent citizens, giving them greater influence in decision-making. The Senate, comprised of lifelong members typically from the patrician class, held significant power in advising elected officials and controlling public spending. Additionally, the patron-client system enabled wealthy patrons to wield influence over their less affluent clients, who often voted according to their patrons’ directions, further entrenching social hierarchies within the Republic.

During the second and third centuries BCE, Rome expanded its territories through a series of conquests, establishing itself as a dominant Mediterranean power. The Punic Wars (264-146 BCE) were a series of three conflicts fought between Rome and Carthage, a powerful North African city-state. These wars featured legendary Roman generals such as Scipio Africanus, who played a crucial role in defeating Carthage, resulting in Rome’s control of the Mediterranean and the eventual destruction of Carthage in 146 BCE. Concurrently, Rome expanded into Greece, where it defeated Philip V of Macedon and his son Perseus, ultimately incorporating Greece into the Roman Empire.

The Roman Republic also faced significant internal challenges during this period, including the Gracchan Reforms (133-121 BCE), initiated by the Gracchi brothers, which aimed to address economic inequality and improve land distribution among the poorer classes of Roman citizens. Additionally, the Jugurthine War (111-104 BCE), fought against Jugurtha, the King of Numidia, tested Roman military capabilities and highlighted issues of corruption within Roman governance. The Cimbric War (113-101 BCE), against the Cimbri and Teutones, further challenged the might of the Roman legions but ultimately ended in Roman victory. Despite these internal and external conflicts, Rome’s economy flourished, and its culture became increasingly Hellenized, meaning it adopted Greek language, art, and customs. This cultural integration laid the groundwork for the Pax Romana, a period of relative peace and stability throughout the Roman Empire. By the late third century BCE, Rome had solidified its position as the premier power in the ancient world, setting the stage for its eventual transformation into an imperial empire.

Rome’s constant wars and conquests during the third and second centuries BCE created numerous social, economic, and political challenges. The traditional system of small family farms, which had defined Roman citizenship, was strained as soldiers were away for extended periods. Upon returning, many found their properties in others’ hands, leading to the emergence of a growing landless working class, known as the proletariat, in Rome. By the first century BCE, the city’s population exceeded one million, disrupting the political system and fostering corruption.

The rise of the proletariat contributed to the decline of the patron-client system, as landless Romans no longer needed patrons to resolve property disputes. Instead, politicians began relying on free food, entertainment, and promises of public works projects to gain support, which created widespread dissatisfaction with the government. Meanwhile, large landowners exploited the demand for grain, wine, and olive oil by purchasing land from impoverished farmers and leasing public land to establish profitable plantations worked by enslaved people.

The availability of enslaved people increased due to Roman conquests and piracy, leading to their cheap purchase and harsh working conditions. This environment fostered massive revolts, including the famous uprising led by Spartacus in 73-71 BCE, which involved hundreds of thousands of enslaved individuals before being violently suppressed. In the aftermath, thousands of rebels were crucified along major roads in Italy. These transformations ultimately set the stage for the downfall of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire.

The End of the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic in the first century BCE faced a deep political and social crisis. Years of expansion, corruption, and inequality created intense pressure on Republican institutions. New classes of wealthy Romans—particularly publicans and contractors—grew frustrated with the dominance of the traditional elite. Publicans who collected taxes in the provinces exploited local populations, and Roman governors ignored the abuse. Political reformers like the Gracchi brothers tried to address these issues by proposing land redistribution, public works, and anti-corruption reforms. Their appeal to popular support outside traditional senatorial channels directly challenged elite authority. Senators responded with violence and killed both brothers. Their deaths triggered the rise of two increasingly polarized political camps: the populares, who sought power by mobilizing mass support, and the optimates, who defended aristocratic privilege and senatorial authority. This division dominated Roman politics for the next century.

Rome’s failures in foreign conflicts—particularly the Jugurthine War in North Africa—revealed the Senate’s inability to address growing military and political challenges. In response, Gaius Marius, aligned with the populares, gained power by promising military reform and quick victories. He opened the army to landless citizens and turned it into a professional force loyal more to generals than to the state. This shift created a dangerous precedent. In the following decades, both Marius and his rival Sulla used their personal armies to march on Rome—Sulla in 88 BCE and Marius in 87 BCE—breaking Republican norms and intensifying political violence. Sulla declared himself dictator, reviving an office unused since the Second Punic War, and imposed sweeping reforms to restore senatorial control. He also ordered brutal purges of his enemies. Although he claimed to save the Republic and later stepped down in 79 BCE, he normalized the use of military power in domestic politics and permanently weakened Republican structures.

Core Impact Skill — Persuasion

In the late Roman Republic, persuasion became a powerful political weapon—used not just to win debates, but to win crowds, armies, and control of the state. Reformers like the Gracchi brothers tried to persuade the Roman people that land redistribution and public works would restore justice, while their elite opponents used fear and tradition to discredit those reforms. Later, generals like Marius and Sulla promised victory, land, and reform in order to gain popular support and loyalty from soldiers. As Republican institutions weakened, public speeches, political promises, and personal ambition replaced legal norms. Persuasion became a way to mobilize the masses—but it also deepened divisions, provoked violence, and led to civil war.

-

What reforms did the Gracchi brothers propose, and how did they try to gain support for them?

-

What promises did Marius make to landless citizens, and how did these promises help him gain power?

-

How did leaders like Marius and Sulla use persuasion to build personal loyalty that challenged traditional Roman institutions?

-

What can this period teach us about how persuasion shapes political loyalty and public trust?

In this fragile environment, three ambitious leaders—Pompey, Crassus, and Julius Caesar—rose to prominence. Each built a political base through military campaigns, patronage, and alliances with discontented groups. When the Senate blocked their ambitions, they formed the First Triumvirate in 60 BCE. Together, they dominated Roman politics, though mistrust and rivalry persisted. Pompey expanded Roman control in the east by defeating pirates, conquering Mithridates of Pontus, annexing Syria, and occupying Jerusalem. These victories secured Rome’s grain supply and signaled deeper religious and imperial entanglements. Crassus, seeking comparable prestige, invaded Parthia and died in the campaign. Meanwhile, Caesar led a decade-long conquest of Gaul and gained massive popularity. After Crassus’s death, Pompey aligned with the Senate and demanded that Caesar disband his army. Caesar refused, crossed the Rubicon in 49 BCE, and launched another civil war, violating Roman law against bringing armies into Italy.

Caesar defeated Pompey at Pharsalus and returned to Rome with unchecked power. He secured appointment as dictator—first for ten years, then for life—and attempted to stabilize Rome by expanding the Senate and offering appointments to former enemies. Many Romans saw him as a tyrant who aimed to destroy the Republic. In 44 BCE, Brutus, Cassius, and other senators assassinated him in an effort to restore Republican rule. Their actions failed. The assassination plunged Rome into more civil war, eventually leading to a final showdown between Mark Antony and Octavian. Octavian won a decisive victory at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE and became the sole ruler of Rome. He claimed to restore Republican values, but in reality, Octavian—soon called Augustus—established the Roman Empire and ended the Republic permanently.

The Roman Empire

In 27 BCE, the Roman Senate granted Octavian the title of Augustus, marking the transition from the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire. Augustus established a new system of government known as the Principate, where the emperor held supreme power while still presenting the illusion of a restored Republic. This shift meant that while the traditional Republican institutions like the Senate still existed, they had significantly less power, as real authority was concentrated in the hands of the emperor. Augustus’s reign laid the groundwork for a period of relative peace and stability, known as the Pax Romana, which had lasting effects on European history.

As emperor, Augustus successfully tackled problems that had plagued Rome for at least a century. He reduced the standing army from 600,000 to 200,000 and provided land for thousands of discharged veterans in recently conquered areas such as in Gaul and Hispania. He also created new taxes specifically to fund land and cash bonuses for future veterans. To encourage native peoples in the provinces to adopt Roman culture, he granted them citizenship after twenty-five years of service in the army. Indigenous cities built in the Roman style and adopting its political system were designated municipia, which gave all elected officials Roman citizenship. Through these “Romanization” policies, Augustus advanced Roman culture across the empire.

Augustus also finally brought order and prosperity to the city of Rome. He began a vast building program that provided jobs for poor Romans in the city and reportedly boasted that he had transformed Rome from a city of brick to a city of marble. To win over the masses, he also provided free grain (courtesy of his control of fertile Egypt) and free entertainment (gladiator combats and chariot races), making Rome famous for its bounty of “bread and circuses.” He also established a permanent police force in the city, the Praetorian Guard, which he recruited from the Roman army. He even created a fire department.

Augustus provided wealthy Romans outside the ranks of the Senate with new opportunities for advancement via key positions he reserved for them, such as prefect (commander/governor) of the Praetorian Guard and prefect of Egypt. These officials could join the Senate and become members of the senatorial elite. Augustus thus created an effective new bureaucracy to govern the Roman Empire. Emperors who followed him continued these practices.

Augustus was keenly aware that the peace and prosperity he had created was largely built upon his image and power, and he feared what might happen when he died. As a result, the last few decades of his life were spent arranging for a political successor. This was a complicated matter since there was neither an official position of emperor nor a republican tradition of hereditary rule. Augustus had no son of his own, and his attempts to groom others to take control were repeatedly frustrated when his proposed successors died before him. Before his own death in 14 CE, Augustus arranged for his stepson Tiberius to receive from the Senate the power of a proconsul and a tribune. While not his first choice, Tiberius was an accomplished military leader with senatorial support.

Despite the smooth transition to Tiberius in 14 CE, problems with imperial inheritance remained. There were always risks that a hereditary ruler might prove incompetent. Tiberius himself became dangerously paranoid late in his reign. And he was succeeded by his grandnephew and adopted son Gaius, known as Caligula, who after a severe illness became insane. The prefect of the Praetorian Guard assassinated Caligula in 40 CE, and the guard replaced him with his uncle Claudius (40–54 CE). The Roman Senate agreed to this step only out of fear of the army. Claudius was an effective emperor, however, and under his reign the province of Britain (modern England and Wales) was added to the empire.

The government of Claudius’s successor, his grandnephew Nero (54–68 CE), was excellent as long as Nero’s mother Agrippina was the power behind the throne. After ordering her murder, however, Nero proved a vicious despot who used the Praetorian Guard to intimidate and execute his critics in the Senate. By the end of his reign, Roman armies in Gaul and Hispania were mutinying. The Senate declared him an enemy of state, and he died by suicide. During the year after his death, 68–69 CE, four different generals assumed power, thus earning it the name “Year of the Four Emperors.”

Of the four, Vespasian (69–79 CE) survived the civil war and adopted the name Caesar and the title Augustus, even though he was not related to the family of Augustus or their descendants (the Julio-Claudian dynasty). On Nero’s death, he had been in command of Roman armies suppressing the revolt of Judea (Roman armies eventually crushed this revolt and sacked Jerusalem in 70 CE). In his administration, Vespasian followed the precedents established by Augustus. For example, he ordered the construction of the Colosseum as a venue for the gladiator shows he provided as entertainment for the Roman masses, and he arranged for his two sons, Titus (79–81 CE) and Domitian (81–96 CE), to succeed him as emperor. Domitian, like Nero, was an insecure ruler and highly suspicious of the Senate; he employed the Praetorian Guard to arrest and execute his critics in that body. In 96 CE, his wife Domitia worked with members of the Senate to arrange for his assassination. Thus the flaws of the principate continued to haunt the Roman state long after its founder was gone.

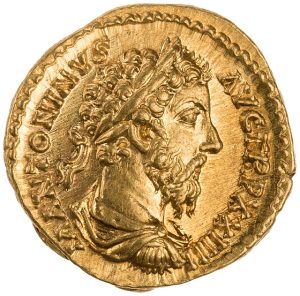

After Emperor Domitian died in 96 CE, the Roman Empire entered a time known as the Five Good Emperors (96-180 CE). This period was marked by the rule of five emperors: Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius, who were known for their wise and just leadership. Trajan expanded the empire significantly, conquering Dacia (modern Romania) and parts of Mesopotamia. In contrast, Hadrian focused on securing these territories and built a lasting border along the Danube River, as well as Hadrian’s Wall in Britain to protect against northern tribes.

Marcus Aurelius, often called the “philosopher-king,” faced many challenges during his reign. He fought wars against various Germanic tribes and dealt with the Antonine Plague, which severely reduced the population and weakened the military. His death in 180 CE marked the start of a turbulent period known as the Crisis of the Third Century. This era was characterized by internal conflicts, corruption, and increasing threats from outside forces. The Year of the Five Emperors in 193 CE highlighted the chaos of the succession crisis, where Septimius Severus emerged as the victor and founded a new dynasty that lasted until 235 CE.

After Severus’s death, the empire experienced more civil wars as different leaders vied for power. External threats from groups like the Goths and Persians also weakened the empire. In 284 CE, Emperor Diocletian took control and introduced major reforms to stabilize the empire. One of his most important changes was creating the Tetrarchy, a system of four co-emperors to help govern the vast territory of the empire more effectively.

While Diocletian’s reforms brought temporary stability, the Tetrarchy eventually failed after his retirement in 305 CE. Constantine the Great, a talented military leader and one of Diocletian’s successors, rose to power in 306 CE. After defeating his rivals, he became the sole emperor in 324 CE. Constantine established Constantinople (modern Istanbul) as the new capital, marking a major shift in the center of power from Rome to the East. His conversion to Christianity and the Edict of Milan in 313 CE granted religious tolerance, which helped Christianity spread throughout the empire. His reign is often seen as a turning point, leading to the rise of the Byzantine Empire and the decline of the Western Roman Empire.

Christianity and the Roman Empire

Christianity originated within the context of 1st-century Judaism, emerging from various Jewish groups in Palestine, especially the Essenes, Nazarenes, and other sects. Jesus of Nazareth, a Jewish preacher and teacher believed to have lived from around 4 BCE to 30 CE, played a key role in this transformation. His teachings drew from Jewish scriptures and traditions, focusing on love, compassion, and the promise of salvation. Early Christians, including Jesus’ disciples, adhered to Jewish laws and customs, seeing themselves as part of the Jewish community. However, Jesus emphasized the spirit of the law over strict ritual, creating tensions with other Jewish groups. His message centered on the arrival of God’s kingdom, the importance of forgiveness, and personal redemption. After Jesus’ crucifixion, his followers, led by the apostles, began spreading his teachings throughout the Mediterranean, setting the stage for a new faith that gradually diverged from traditional Judaism.

Learn More

The establishment of Christianity as a distinct religion was significantly influenced by key figures like Paul of Tarsus. Paul was instrumental in reaching out to Gentiles (non-Jews) and emphasized that faith in Christ was more important than strict adherence to Jewish law. His letters to early Christian communities became foundational texts that helped define Christian beliefs. Despite its growing appeal, the early Christian community faced persecution from Roman authorities, who viewed it as a challenge to traditional Roman values and religions. This was particularly true under emperors like Nero, who began persecutions in 64 CE; Domitian, who intensified hostilities around 90 CE; and Diocletian, who launched a widespread crackdown on Christians in 303 CE. Despite these challenges, the faith spread rapidly throughout the Roman Empire, supported by devoted missionaries, the martyrdom of believers, and intellectual defenses from early Christian thinkers like Origen.

The growing success of Christianity in the 4th century CE significantly influenced Constantine’s decisions during his struggle for control of the Roman Empire. In 312 CE, Constantine faced his rival Maxentius at the Battle of Milvian Bridge, near Rome. According to legend, before the battle, Constantine had a vision of the cross accompanied by the inscription In Hoc Signo Vinces (“In this sign, you will conquer”). He interpreted this vision as a divine sign, which prompted him to embrace Christianity and subsequently adopt it as his favored religion. While historians debate the specifics of Constantine’s conversion experience, it is widely acknowledged that his Edict of Milan (313 CE) granted religious tolerance to Christians, effectively ending years of persecution and facilitating the rapid spread of Christianity throughout the Empire. Additionally, Constantine convened the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE to address theological disputes within Christianity and established Constantinople as the new capital, further solidifying Christianity’s influence and position within Roman society. These actions fundamentally altered the course of Western history, marking a pivotal shift in the relationship between the state and religion.

With Constantine’s backing, Christianity spread rapidly throughout the 4th century CE. Despite efforts by Julian the Apostate, Rome’s last pagan emperor, to revive traditional paganism from 361-363 CE, Christianity continued to gain momentum. Emperor Theodosius eventually banned paganism altogether by 395 CE, making Christianity the official state religion. Just 83 years after Constantine’s initial support, Christianity had become the dominant force in Rome, gradually replacing paganism, which lingered for another century before fading out.

Core Impact Skill: Persuasion

As you explore the early history of Christianity, consider how its teachings, stories, and growing political support helped it spread throughout the Roman world. Christianity began as a small movement within Judaism, but over time, it became a powerful force that reshaped Roman society. This shift did not happen through military power—it happened through persuasion: the ability to inspire belief, build communities, and eventually align with imperial authority.

Persuasion helps you see how early Christians used messages of hope, redemption, and eternal life to connect with people from all walks of life. Stories about Jesus, the moral example of believers, and the courage of those who suffered for their faith made the Christian message deeply compelling. As the movement spread, it challenged traditional Roman values and beliefs. When Emperor Constantine later supported Christianity, he added a new kind of persuasive power—political legitimacy. His actions sent a message that Christianity was not only spiritually meaningful, but also compatible with Roman leadership and imperial identity.

-

What kinds of messages helped Christianity gain followers across different regions of the empire?

-

How did early Christian communities use storytelling and example to persuade others?

-

Why did Roman authorities see Christianity as a political threat before Constantine?

-

How did Constantine’s support for Christianity change its role in public life and strengthen its influence?

By studying how early Christians persuaded others—through words, actions, and political alliances—you are learning how ideas can shape entire societies. That’s the power of persuasion: not just in speeches, but in symbols, stories, and the decisions that link belief to power.

The relationships between pagans and Christians grew increasingly strained. Initially, elite pagans could still pursue a career and hold public office, as did the noted intellectuals Libanius and Symmachus. Yet episodes of violence also occurred in the cities of the empire where Christian bishops wielded both religious and political power. The murder of the influential pagan scholar and teacher Hypatia in Alexandria in 415 demonstrates how a bishop could wield extralegal authority. Bishop Cyril viewed Hypatia, who had a large friendship network of Christians and pagans, as a political threat, and he was able to convince the Christian populace to attack and kill her. This secured his own position as a substantial political and religious authority in the city.

Link to Learning

Learn more about the pagan teacher and scholar Hypatia of Alexandria (https://openstax.org/l/77Hypatia) in this video. Hypatia’s teaching of mathematics and philosophy was viewed as a threat to the Christian order in the city, which ultimately led to her demise.

Constantine’s rule also marked a significant geographical shift for the Roman Empire. After reunifying the Empire in 324 CE, he moved the capital from Rome to Byzantium, renaming it Constantinople. This strategic location offered several advantages, including an excellent harbor, proximity to the Persian and Danube frontiers, and a fresh start for the Empire. Constantine’s vision for a “New Rome” signaled a new era for the Roman Empire, now with a Christian capital. This move marked the end of Rome’s reign as the imperial capital, paving the way for Constantinople to become the epicenter of Eastern Roman, or Byzantine, power.

The consequences of Constantine’s decisions ultimately led to the division of the Roman Empire into Eastern (Byzantine) and Western halves. In 395 CE, Theodosius’ sons, Arcadius and Honorius, inherited the Eastern and Western Empires, respectively. As the Western Roman Empire faced relentless barbarian invasions, its power waned, and it eventually fell to the Visigoths in 476 CE. Meanwhile, the Eastern Roman Empire, with Constantinople as its capital, continued to thrive for another thousand years, preserving Greek and Roman culture, and becoming a bastion of Orthodox Christianity. This division marked the beginning of distinct Eastern and Western European identities, shaping the course of history for centuries to come.

The “Fall” of the Western Roman Empire

After Constantine established Constantinople as the Eastern Roman capital, the Western Roman Empire encountered increasing pressure from external threats and internal instability. A series of barbarian invasions, particularly from Germanic tribes like the Visigoths, Vandals, and Ostrogoths, significantly weakened the Western Empire’s military resources. A critical turning point occurred in 378 CE when the Visigoths defeated and killed Emperor Valens at the Battle of Adrianople. This defeat highlighted the vulnerabilities of the Western Empire, which struggled to maintain its borders. In 406 CE, the Rhine River frontier was breached, allowing Alaric and his Visigoths to sack Rome in 410 CE. This shocking event sent shockwaves through the Empire, prompting St. Augustine to write “The City of God” as a response to the crisis of faith and societal turmoil. Despite some brief stability under emperors like Theodosius II and Majorian, the decline of the Western Roman Empire only accelerated.

The final blow came in 476 CE when Odoacer, a king of Germanic origin, deposed the last Western Roman Emperor, Romulus Augustulus. This marked the official end of the Western Roman Empire. Following this collapse, Western Europe fragmented into smaller kingdoms and city-states, paving the way for the Middle Ages. Meanwhile, the Eastern Roman Empire, later known as the Byzantine Empire, continued to thrive by preserving Roman law, culture, and Orthodox Christianity. As the Western Roman Empire fell, its legacy persisted, profoundly shaping European politics, culture, and identity. The decline of Western Rome also facilitated the rise of new powers, including the Franks and Lombards, and eventually led to the establishment of the Holy Roman Empire. The divide between Eastern and Western Europe, initiated by Constantine’s decision to establish Byzantium as the new capital, became a lasting reality that would influence the course of European history.