34 The Post-Roman West

Of all the regions in the post-Roman world, western Europe experienced arguably the most dramatic change. Its political order fragmented under Germanic warlords empowered mainly by their ability to provide loot for their followers. In this world of soldiers, the Roman church, directed by the pope, worked to secure military assistance from kings and convert various groups to Christianity. The church’s goal was to ensure that its vision of Christian beliefs and practices eclipsed those of other sects such as the Arians, Christians who questioned the Roman church’s basic tenet that Jesus was divine. The merging of these two antithetical cultures—the religious and the military—helped prepare the ground for a new civilization we call the medieval culture, which emerged between the end of Rome and the rise of the modern world.

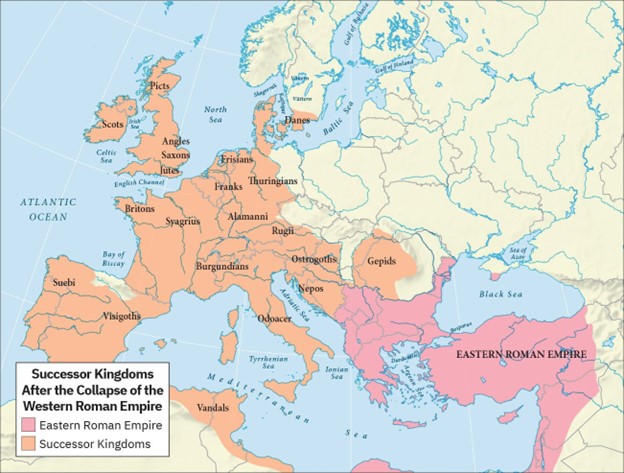

Europe after the Roman Empire

There was no exact date when the Roman Empire fell, and the eastern half of the empire did not collapse until the fifteenth century. In fact, the Germanic peoples who settled in the former Roman Empire were not hostile to its culture, so in some places, Roman culture lasted longer than Roman political authority. Latin remained the language of the educated, for example, and Germanic peoples gradually adopted the Latin alphabet for their own languages, including English. Traditionally, though, the end of the empire is fixed at 476, when a German general named Odoacer deposed the emperor Romulus Augustulus and established himself not as a Roman emperor but as King of Italy. Even that date may be arbitrary, but by the late fifth century, traditional Roman authority had ceased to be the basis of political power in much of western Europe.

The authority of the successor kingdoms gradually replaced Roman political authority. The Germanic peoples and the Roman population they conquered were able to create a new society by blending cultural traditions—a process called acculturation—in three ways. First, conversion to Christianity helped reduce differences between the two groups. Second, the Christian Church and the Roman aristocracy offered a useful example of bureaucratic organization and diplomacy that the successor kingdoms adopted. Finally, the erosion of Roman society enabled a new society to emerge in the Middle Ages. Although other Germanic kingdoms existed, those established by the Franks, Ostrogoths, and Visigoths demonstrate these three forms of acculturation most vividly.

As an example of acculturation, Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths, was one of the most dynamic leaders of the post-Roman world. When he became King of Italy in 493, he relied on Roman aristocrats to administer his kingdom, such as the scholar and writer Cassiodorus and the historian and philosopher Boethius. Theodoric also rebuilt Roman infrastructure, including repairing aqueducts and city walls in his kingdom. He used diplomacy to secure alliances with other German kings, often through marriages. To form an alliance with the Franks, for instance, he himself wed Audofleda, the sister of Clovis I, king of the Franks, and he gave his daughters in marriage to other Germanic kings. Envisioning himself as the heir to Roman rule in the west, he maintained ties with the eastern Roman emperors and strove to revive trade with the eastern Mediterranean world. Despite the struggle to maintain order, most rulers attempted to connect with distant civilizations and learned from the peoples around them.

To create common bonds between Romans and Germans, Theodoric settled the Ostrogoths among the Roman population, although religious differences kept them from fully integrating. Toleration was possible and even desired in the early Middle Ages, but distrust between religious groups could spark outright violence and persecution. While he was an Arian Christian, Theodoric tolerated the Catholic population of Italy and attempted to mitigate conflict between the two groups until late in his reign, when his distrust of Catholics led him to persecute them. After his death in 526, the Ostrogoths struggled in Italy, and invasion by both the Byzantines and new invaders called the Lombards left the land devastated and divided.

The Franks

The most successful Germanic kingdom was that of the Franks (a group that inhabited what is now France and parts of Germany), founded by Clovis I in the early sixth century as a member of the Merovingian dynasty. Clovis stands in striking contrast to Theodoric, exhibiting a ruthless yet cunning leadership style. He recognized the advantages of diplomacy, particularly through forging an alliance with the Catholic Church, and demonstrated a level of tolerance for religious differences until his own conversion to Catholicism. By collaborating with Gallo-Roman aristocrats and clergy, Clovis strengthened his kingdom’s administration and ensured the continuation of Roman institutions wherever possible. Just before his death, he convened the first council of Catholic bishops at Orleans, which produced proclamations binding on both the Gallo-Roman population and the Franks. In this instance, religion served as a unifying force, bridging the gap between two culturally distinct groups.

However, over time, the Merovingian rulers descended into violent infighting, leaving behind young and often ineffective successors. This instability stemmed largely from the practice of partible inheritance, where each son received an equal share of his father’s estate. As a result, estates diminished in size with each generation unless new lands were conquered, often taken from siblings or cousins, leading to further conflict. Kings lacking land and resources struggled to attract fighters, resulting in a power shift to the aristocrats. Eventually, the Carolingian dynasty emerged, taking control of the Frankish kingdom. With the backing of the pope, Pépin le Bref (Pippin the Short) deposed his Merovingian rival, becoming the first Carolingian king. In return, he granted lands in Italy to the pope, known as the Donation of Pepin, which provided the legal foundation for the establishment of the Papal States and transformed the papacy into a territorial power, not merely a religious institution. This alliance with the popes enabled the Carolingian rulers to operate independently of the Byzantine Empire, fueling their ambitions to conquer new territories and revive the concept of empire. It also underscores how, even in the chaotic aftermath of Roman authority’s collapse, diplomacy, religious movements, conflict, and opportunities continued to intertwine the Mediterranean world with Western Europe.

Pépin’s son Charles, known as Charlemagne (“Charles the Great”), was the most influential ruler in the early European Middle Ages and one of its best-known figures. Charlemagne was fortunate, as his father had been, in that he did not need to fight his siblings for control of the kingdom. He was tall and energetic and had a profound belief in his role as a Christian ruler, with a will to conquer others and convert them to Catholic Christianity. He campaigned nearly every year of his reign, conquering land and subjugating peoples across central Europe. He reorganized his government and attempted to revive learning, reform the church, and extend his influence beyond his own realm. His vast empire eventually extended from modern France to Germany, northern Italy, and parts of northern Spain and central Europe, uniting western Europe for the first time since the collapse of Roman authority. On Christmas Day in the year 800, Charlemagne was crowned Emperor of the Romans by Pope Leo III. This coronation angered Byzantine rulers and set the stage for conflict between east and west in their quest for prestige and territory. It also enabled both cooperation and conflict between popes and emperors, because each saw an advantage in working together to fight mutual enemies.

Like Theodoric, Charlemagne was more than a conqueror. He hoped to revive Roman institutions, reform the church, and convert people to Christianity. The period of intellectual activity and reorganization of educational and religious institutions that began in his reign is often called the Carolingian Renaissance, meaning a “rebirth” of culture and learning (and “Carolingian” being a reference to Charlemagne). The Carolingian aristocracy supported the building of new palaces and monasteries and promoted artists to decorate these buildings as well as to illustrate (or “illuminate”) books, and the increased emphasis on learning was a way to ensure that the court of the Carolingians was filled with highly educated advisers and associate.

Intellectuals and monks flocked to Charlemagne’s court, where they put their talents to use copying the classical works of ancient Greek and Roman authors and serving in the emperor’s administration. One of the most important of these scholars was Alcuin of York, an Anglo-Saxon who perfected the Carolingian minuscule script. This standard form of handwriting was clearer and easier to read than earlier Roman and Merovingian forms. Carolingian scholars also popularized punctuation marks, like the sentence-ending period. These innovations made it easier for people to learn Latin and contributed to the revival of classical education. Charlemagne was also a globally minded ruler. He corresponded with the Byzantine rulers, received gifts from the Abbasid caliph, and facilitated the trade of enslaved people taken on his eastern frontier with Al-Andalus (modern Spain).

Charlemagne’s empire, despite its initial grandeur, did not endure. He was succeeded by his son, Louis the Pious, who continued the revival of learning and engaged in significant church reforms. Recognizing the decline in both spiritual and administrative matters, Louis appointed figures like the monk Benedict of Aniane to spearhead reform efforts across the Frankish Empire’s monasteries. These reforms included strict guidelines on monastic life, detailing what monks could eat, how they should work, and when they should pray. The Carolingian reformers drew inspiration from Irish monks, who brought with them a distinctive ascetic practice and meticulously copied classical literature. As a result, the revitalization of monasteries played a crucial role in preserving both the cultural achievements of the Carolingian era and the foundational texts of classical learning.

Despite Louis’s influential religious and intellectual initiatives, the inherent weaknesses within the Carolingian state undermined his efforts. Unlike his father, Louis was not perceived as a formidable warrior, prompting soldiers to seek glory and plunder elsewhere. His own sons, eager for power, rebelled against him during his lifetime, eventually forcing him to abdicate. In 843, the empire was divided among them according to the principle of partible inheritance, formalized in the Treaty of Verdun. This division created three distinct territories: the Kingdom of the West Franks, the Kingdom of the East Franks, and a middle region known as Lotharingia, which included parts of Italy. However, none of Louis’s sons were satisfied with this settlement, leading to ongoing conflicts over land and power, which further destabilized their kingdoms. As a result, the aspirations of Charlemagne and Louis to forge a unified Christian state under Germanic leadership gradually crumbled.

These internal challenges were compounded by external threats, particularly from new invaders emboldened by the decline of Carolingian power. From the east came the Magyars, nomadic raiders migrating from the steppes of Central Asia. Settling in present-day Hungary by the end of the ninth century, they launched devastating raids into Germany until they were ultimately defeated by King Otto the Great at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955. Simultaneously, the fragmentation of Islamic political unity allowed petty rulers to raid the weakened coasts of Christian Europe, with North African dynasties like the Aghlabids targeting Sicily and even launching raids as far as Rome by 846. Meanwhile, the Vikings, originating from Scandinavia, introduced a new wave of violence in northern Europe. Sharing cultural traits with earlier Germanic peoples, they engaged in polytheistic worship and maintained a warrior aristocracy. Driven by population growth and a lack of arable land, groups of Danes, Norwegians, and Swedes embarked on expeditions for plunder, leading to a complex interplay of trade, settlement, and violent raids that would reshape the landscape of medieval Europe.

Europe after Charlemagne

Following the decline of the Carolingian Empire, medieval Europe developed a social hierarchy known as feudalism, primarily driven by the need for security and protection. This system was marked by unequal relationships between lords and vassals. To safeguard their territories and the peasants who worked the land, lords granted land, known as fiefs, to warriors in exchange for military service and loyalty. Vassals swore allegiance to their lords, pledging to provide counsel and attend court when called upon. Similarly, bishoprics and monasteries operated as lordships, with abbots and abbesses owing service to higher lords.

Feudalism was not a formal political system but rather a web of obligations that connected warriors to lords and lords to kings. Theoretically, the king was the largest landowner and the guarantor of rights. For instance, Charles the Simple granted the Duchy of Normandy to the Viking leader Rollo in exchange for protecting northern France. However, monarchs often undermined their own power by granting lands and privileges to appease their feudal lords. In return, kings sought strategic marriages, dowries, and occasionally suppressed rebellious vassals to reclaim lost lands. Under the manorial system, warriors managed agricultural laborers on their fiefs. Most laborers in Western Europe were serfs, who were unfree and bound to the land. While not enslaved, serfs occupied the lowest social rung, facing physical abuse, labor demands, and limited rights. Lords protected serfs, resolved disputes, and oversaw their work. Serfs owed their lords annual service, could not leave the land or marry without permission, and paid tithes to the church. This hierarchical structure shaped the economic and political landscape of medieval Europe, blending Roman, Christian, and Germanic traditions. By the 10th century, the legacy of the Roman Empire had diminished, giving way to a new society legitimized by medieval kings and nobles.

As Christianity became more established in Europe, it ironically became the custodian of classical Greek and Roman heritage, preserving law, literature, and philosophy. However, the unity of the Christian Church faced challenges due to linguistic and cultural differences between its Eastern and Western branches. Disputes over the use of religious images and the supremacy of the papacy strained relations, especially in the 8th century. Popes like Leo I laid the groundwork for the authority of Roman bishops, which the Eastern churches largely rejected. The papacy formed alliances with Frankish kings, shifting its focus to Western Europe. This partnership allowed the Church to reshape the remnants of the old Roman world. Three key factors contributed to this transformation: the conversion of Germanic peoples to Christianity, the preservation of classical traditions, and the legitimization of new rulers’ authority. Missionaries, including monks and laypeople, played a crucial role in these efforts. Pope Gregory’s commission of Augustine of Canterbury exemplified this initiative, as did the influential work of queens like Clothilde and Bertha in promoting conversion within their husbands’ kingdoms. Monasticism thrived in Western Europe, offering communal life for devoted men and women. Benedict of Nursia’s Rule emphasized balance, self-sufficiency, and education, while double monasteries, such as Radegund’s Monastery of the Holy Cross in Poitiers, provided women with autonomy and influence outside traditional family roles. Abbesses like Radegund gained significant authority, showcasing the diverse opportunities available to women in medieval society.

Building on their role in preserving knowledge, monastic communities played a crucial part in legitimizing new rulers in the post-Roman world. Conversion to Catholic Christianity allowed Germanic kings to integrate with their Roman subjects, while bishops administered and monasteries educated the emerging elite. However, Charlemagne’s reign raised questions about the relationship between rulers and the papacy, particularly concerning the ceremonial role of clergy in anointing kings. As Catholic Christianity established its dominance, Jewish communities faced increasing persecution and marginalization. Clergy and kings imposed harsh restrictions, fueled by anti-Semitic sentiment and misconceptions about Jewish responsibility for Jesus’ death. In Visigothic Spain (711-718 CE), Jewish residents were forced to choose between conversion and expulsion, while in other regions, they suffered violence, segregation, and economic exploitation. However, these measures were often overshadowed by the rampant anti-Semitism prevalent among clergy and nobles. The precarious position of Jewish communities in medieval Europe resulted from a complex interplay of factors. Local attitudes varied, with some regions tolerating Jewish presence while others enforced brutal suppression. Economic interests sometimes influenced rulers’ decisions but rarely alleviated the widespread hostility toward Jewish people.

Core Impact Skill — Perspective-Taking

The history of the Christian Church in medieval Europe offers multiple opportunities to practice perspective-taking. From the papacy’s alliances with Frankish kings to the missionary work of abbesses and queens, and from monastic contributions to education and governance to the persecution of Jewish communities, the same events looked very different depending on the observer. For a Benedictine monk, the spread of Christianity might have been a divinely inspired mission to unify and civilize. For a Jewish merchant in Visigothic Spain, it might have signified coercion, loss of livelihood, or forced exile. For a Frankish ruler, papal blessing could legitimize authority; for leaders in the Eastern Church, it might represent an overreach of Roman influence. Practicing perspective-taking means using evidence to imagine how people in these varied positions understood their circumstances, shaped by religion, culture, and political realities. This skill is essential for avoiding single-story narratives and for appreciating the complex, and sometimes conflicting, ways historical actors experienced the medieval world.

-

Based on historical evidence, how would different groups—such as Western clergy, Eastern Christians, Jewish communities, and secular rulers—have understood the papacy’s growing power in medieval Europe?

-

How can comparing these viewpoints help us identify the limits of our own perspective when studying history and analyzing contemporary issues?

Life for ordinary people in medieval Europe at this time was characterized by a rigid social structure and significant hardships, particularly for women and minority populations. Most people lived in rural areas, working as peasants on manors owned by lords. Their daily lives revolved around agricultural labor, which included planting and harvesting crops, tending to livestock, and managing household duties. Men typically engaged in fieldwork and skilled trades, while women were responsible for domestic chores, childcare, and helping in the fields when needed. Despite their crucial roles, women had limited rights and often depended on their husbands or fathers for legal and economic standing.

In urban centers, a small but growing population engaged in various trades and crafts, such as blacksmithing, weaving, and baking, often organized into guilds that regulated working conditions and quality standards. However, for many minority populations, such as Jews and other marginalized groups, life was fraught with discrimination and violence. They faced economic restrictions, limiting their ability to own land or participate in certain trades, and were often subjected to scapegoating during times of social unrest, resulting in persecution and forced conversion. The intertwining of gender roles and minority status meant that women from these groups endured double layers of hardship, facing not only the societal constraints imposed on all women but also the additional burdens of anti-Semitism or other forms of prejudice. Overall, ordinary life in medieval Europe was marked by a struggle for survival amid economic limitations, social inequalities, and the threat of violence, which profoundly shaped the experiences of its diverse populations.