35 The Crusades

The chaotic aftermath of the collapse of the Carolingian Empire led to a complicated situation between secular rulers and the Christian Church. According to German law, lords had the right to control everything on their land, including churches and monasteries. This control even extended to the appointment of officeholders to church positions such as abbot or bishop. To ensure they had the loyalty of church officials, lords staffed these offices with their family members or even sold them to the highest bidder. The consequence was that those without religious vocations, or even familiarity with Christian doctrine, could be installed into church leadership. Even the position of the pope, the bishop of Rome, could come up for sale.

Revulsion at this treatment of religious office led to a reform movement intended to remove the influence of secular lords from the management of the church. The movement is often associated with the monastery of Cluny in France, which managed to get independence from the local aristocrat. Other monasteries around France flocked to be included in the rights and privileges that Cluny had earned, creating a movement called the Cluniac reform. The Cluniac movement eventually drew in other clergy who wanted the church to control the election of bishops, independent of secular influence. This desire for independence finally reached the top of the Catholic Church and the office of the bishop of Rome.

The bishops of Rome were eventually influenced by the Cluniac movement to reform the church. They condemned the sale of offices as a sin called simony and insisted that bishops should be elected by clergy, independent of a lord. Any clergy member who had bought an office or had it bought for them could be removed. To end the practice of treating church positions like a fief to be passed on to the officeholder’s children, priests were told to practice celibacy and were forbidden to marry. While celibacy was not a new concept in the Catholic Church, reforming monks and popes began to enforce it with energy. These changes caused bitter conflict with the rulers of Europe, so the church declared that a king who tried to appoint a bishop or asked for a bribe could be excommunicated (placed outside the church, its communion, and the sacraments, in hopes of reforming the offender). Excommunication could threaten the king’s position and lead to rebellions.

The reformers were also interested in creating a thoroughly Christianized society by distinguishing between legitimate and illegitimate warfare. The church argued that Christian soldiers, especially knights, should obey a code of conduct that reflected the church’s values. For example, they should not loot monasteries or hold clergy for ransom. They should protect the church as well as women and the defenseless. They should observe periods of publicly declared truces and not fight on religiously significant days like Easter. These principles contributed to the ideals of chivalry, a code of conduct that was meant to Christianize knightly violence and behavior. Although it was never successful at curbing violence, the idea of Christianized warfare was only one strand of a broader, secular interest in a newly defined chivalric culture of knighthood, and images of Christian knights helped popes justify their directing the military classes of Europe to act against peoples deemed to be enemies of the church, and therefore also of God.

The reform movement gained the church some moral prestige, but the growing power of the pope also worsened the relationship between the eastern and western halves of the faith. By the time of the Middle Ages, five ancient seats of Christianity were recognized as the most prestigious: Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria, Rome, and Constantinople. Each was led by a bishop with the honorary title of “patriarch.” In the tenth century, only Rome and Constantinople were in territory not controlled by Muslims.

While the pope in Rome and the patriarch of Constantinople believed many of the same things, linguistic and cultural differences helped drive a wedge between them. For example, the church in the west operated in Latin, insisted on a celibate clergy, and elevated the pope as the final authority for all matters regarding the church everywhere. The church in the east used Greek, permitted priests to marry (although tradition held that bishops should be unmarried), and believed other patriarchs were just as authoritative as the pope. The reform movement unintentionally made divisions sharper.

In 1054, the pope sent representatives to the patriarch of Constantinople to discuss the differences between the two halves of the church. The pope’s chief representative felt the patriarch was not cooperating with or even recognizing the embassy, so he issued a letter excommunicating the patriarch and his followers. Soon after, the patriarch issued his own letter excommunicating the pope’s representatives. Following this Great Schism of 1054, the eastern church became known as the Eastern Orthodox Church, and the western half the Catholic Church.

The Great Schism was not the only cause of their division, given that tensions and disagreements had been growing over time. But it did help to highlight the way Christianity was being shaped by different forces in different parts of Europe. From this time on, the popes hoped to reunite the two halves under their authority and impose their vision of a reformed church on the Orthodox Church. While Orthodox bishops might accept the pope as “first among equals,” the papacy insisted on being the supreme authority in the church.

Pope Urban II and the Council of Claremont

In 1095, facing invasion on all sides, the Byzantine ruler Alexios I sent ambassadors to plead for help from the pope and an opportunity for a reconciliation between the two churches. Pope Urban II was a supporter of church reform, and that put him at odds with German emperors like Henry IV, who insisted on his own right to appoint bishops, even the bishop of Rome. To avoid being in Italy when Henry was, Urban traveled throughout western Europe, preaching repentance from sins and obedience to the church. He answered the Byzantine emperor’s call for aid, but in a way Alexios was probably not expecting.

Urban II presented his idea of religious war in response to the Byzantine request for aid at a council in Clermont, France, in 1095. While the council was ostensibly about reform, Urban also issued a call for Christians from all walks of life to undertake an “armed pilgrimage” to liberate the Christian Holy Land (the lands of the eastern Mediterranean associated with the life of Jesus and the biblical prophets, including Jerusalem) from “Turkic” control. Urban’s goal at this point was to free the Holy Land from non-Christian rulers in defense of the Christians living there; it was not a blanket endorsement of violence against Muslims. These limitations were later eased, however, as the popes discovered the power of calling repeated crusades to promote the reforming goals of the church and to compete with political rivals in Europe, like the German emperors.

While the Byzantine emperor wanted aid for his realm, Urban instead sent the crusaders to Jerusalem. Urban’s directive to “liberate Jerusalem” and support the Christians in the Middle East was clever. Few Europeans knew or cared about the problems of Constantinople, but the church’s reforming and educational efforts had made the life of Jesus in Jerusalem and the early Christian community there a focal point in people’s imaginations. Catholics prized relics of saints as a means of fostering their devotion and bringing them closer to the divine, and Jerusalem was in effect an enormous relic, a gateway to heaven itself. Preachers like Peter the Hermit whipped up crowds of men and women with the idea of a glorious pilgrimage to the most sacred of cities. The call to crusade stirred western Christians into action, soldiers and knights as well as poor peasants and zealots.

Urban also hoped to restore unity to the church by offering help to the Byzantine Empire. What we know of his speeches shows how he tied this effort together with his reform program. Freeing Jerusalem from “the wicked” would mirror the rallying cries to free the church from aristocratic control. After all, the reason Urban called for the crusade while in France was that he had to contend with a rival pope, supported by the German emperor, who had occupied Rome since before Urban became pope. Urban was also likely concerned about guarding the frontiers of Christianity, which compelled him to insist that Spanish Christians should not go on this pilgrimage because they were needed at home in the persistent struggle against Islam in the Iberian Peninsula.

Finally, Urban’s ability to inspire the people of Europe signaled the influence he wielded over Christians at large. The popes had no armies, and they often had to depend on the unreliable aristocracy for protection when disagreements over church policy resulted in armed conflict with the princes of Europe. If they were to maintain their control over the church in contests with kings and emperors, it would be useful to see what happened when a pope rallied common Christians to a religious cause as a test of faith. Thousands were willing to stitch a cross onto their clothes, a sign that they were on this special pilgrimage and the source of the word “crusade.”

Core Impact Skill — Persuasion

The call for the First Crusade shows how persuasion can unite diverse audiences behind a single cause by linking spiritual devotion with political necessity. Pope Urban II framed the liberation of Jerusalem from “the wicked” as a sacred duty, but he also tied it to his reform program to free the church from aristocratic control. Speaking in France while contending with a rival pope backed by the German emperor, Urban combined religious imagery, moral urgency, and strategic direction—such as telling Spanish Christians to remain home to defend the Iberian Peninsula—into a message that inspired action across Europe.

We learn about persuasion by studying how Urban appealed to people from all walks of life, from nobles to poor commoners, women, the sick, and the elderly. His speeches inspired thousands to sacrifice property, endure hardship, and take up the cross as a visible sign of commitment. Yet the same rhetoric also fueled hostility toward Jewish communities, leading to extortion, violence, and long-term insecurity. Persuasion here was a double-edged sword: it could inspire unity and devotion, but also justify exclusion and harm.

-

How did Urban’s combination of spiritual, political, and strategic appeals strengthen the persuasive power of his message?

-

What does the impact of his rhetoric—both inspiring and harmful—reveal about the responsibilities of those who use persuasion to mobilize large groups?

By examining this moment, we gain insight into how persuasive communication can shape events on a massive scale, influencing not only immediate actions but also the broader cultural and political landscape for generations.

In response to Urban’s message, commoners (even poor ones), women, the sick, and the elderly joined alongside knights, and powerful nobles to answer his call. Many sacrificed their own land and property to gain the resources needed to join the crusading movement. The trek to Constantinople alone was arduous, with few amenities or roads to guide the way. Some may have hoped to gain land if they remained in the Holy Land, and others were motivated simply to see the earthly Jerusalem as a way of experiencing the heavenly Jerusalem that awaited them when they died, and then returned home.

Others had less altruistic motives. The rhetoric preached about non-Christians made Jewish communities, like those in the Rhineland, vulnerable to attack by crusaders seeking plunder, who extorted bribes from Jewish communities to leave them in peace. Even those whose motivations were clearly religious, like Peter the Hermit, compelled German Jewish people to render supplies for their crusading bands. Although the church condemned violence, the Crusades mark the beginning of precarious times for Jewish communities in Christian Europe, when they were subject to abuse, expulsion, and sudden violence.

The call to crusade had profound consequences for Islamic and Christian societies. The military fortunes of the crusaders were watched carefully by Muslims and Christians alike, and while the success of the First Crusade was shocking to everyone, to Christians it was also a clear sign of God’s favor. The flaws in the crusading movement grew or became better known over time, however. Fewer Christians joined later crusades, even though the legend and romance of the venture became more popular in the European imagination.

The First, Second, and Third Crusades

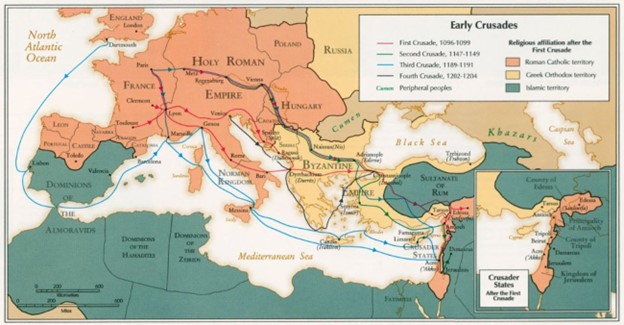

Historians have categorized the different crusades and given them numbers for convenience and to distinguish between various developments within the crusading movement. The Crusades were rarely well organized, however, and one of the challenges they all faced was trying to move people from one end of Europe to the other. For example, during the First Crusade, the followers of Peter the Hermit arrived in Constantinople first. They did not wait for other groups to arrive and were ferried over to Anatolia (the Asian part of today’s Turkey) by Alexios, the Byzantine ruler. The Turks destroyed this army, and very few survived to return to Constantinople. Later crusaders understood that gathering intelligence in Constantinople was crucial to avoiding Peter’s fate.

The bulk of the First Crusade was directed by powerful aristocrats whose armies were better organized and prepared to fight than Peter’s, even if most of its participants were not the most senior nobles of Western society. Alexios promised them aid in exchange for the return of Byzantine territory held by Muslims, which most initially agreed to. The crusaders crossed Anatolia and, after laying a bloody siege with little help from the Byzantines, took control of the port of Antioch, an ancient seat of Christianity in the Holy Land. After their victory, they felt Alexios was undeserving of either the city or their fidelity. The city was thus given to a crusader who had no intention of delivering it to Alexios, straining the relationships between the crusaders and the Byzantine Empire.

The First Crusade finally reached Jerusalem in the summer of 1099. Before attacking the city, the crusaders fasted and walked around its walls as penitents, an act that shows the blending of pilgrimage with armed conflict. The crusaders then took the city, and in an act that shocked Muslims and Christians alike, they massacred the Muslim and Jewish inhabitants. The crusading armies then took other important cities in the area, and to secure their control they established the four Crusader States: the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, the County of Tripoli, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem. These Crusader States were also called Outremer (literally “overseas”) by the French, and they claimed Jerusalem as their capital. Of all the Crusades, this was the only one that accomplished its objective.

Despite the surprising success of the First Crusade, Outremer suffered some critical problems from the beginning. The crusaders had alienated the Byzantine Empire by not returning to it important cities like Antioch or lands in the Middle East as they had promised. The European aristocrats and knights were eager to acquire lands for themselves, which meant they often fought with each other even when faced with a common enemy. And while there was always at least a trickle of warriors who made it to Outremer, the elite remained in desperate need of soldiers to defend their new territories.

Link to Learning

Recent media representations have tried to portray a realistic view of the Crusades that includes their internal factionalism and intolerance, but realism often gives way to a filmmaker’s need for a more compelling character, a more stylish scene, or the inclusion of inappropriately modern sentiments. Follow the link to read a historian’s review of the 2005 Ridley Scott crusader film (https://openstax.org/l/77scottfilm) Kingdom of Heaven.

The Second Crusade, from 1147 to 1149, was heralded by a new generation of preachers like Bernard of Clairvaux who inspired believers to “take up the cross.” Bernard also wrote the rules for the Knights Templar, one of the new crusading orders, religious orders of monks devoted to protecting Christian pilgrims and fighting to support Outremer. This crusade was led by powerful rulers, including King Louis VII of France and King Conrad III of Germany. The armies of the Second Crusade were defeated in Anatolia in separate battles, and few soldiers reached the Holy Land. The kings accomplished very little, and many blamed the Byzantine emperor, who had learned to be distrustful of European armies. Bernard of Clairvaux was humiliated and apologized to the pope, claiming the sins of the crusaders had caused the defeat. It was a disaster that seemed as complete as the First Crusade had looked miraculous.

After this loss, the situation for Outremer only became more dire. Imad al-Din Zengi’s successors were well liked, even by crusaders, and they strove to unite the Muslim princes in jihad. The most famous of these successors was Salah al-Din, or Saladin in the Christian world. He was known for being humane, fair-minded, and, in Christians terms, chivalrous. He expanded his territory from Syria into Egypt and founded a new dynasty called the Ayyubids from the ashes of the Shia Fatimid Caliphate. He also took up his religious calling to wage jihad against the crusaders. In 1187, after years of gathering allies and eroding the military power of Outremer, he destroyed the crusaders at the Battle of the Horns of Hattin (in today’s Israel). Within months, Jerusalem fell to Saladin.

The Christians’ response was the Third Crusade (1189–1192). This crusade was prompted both by the fear that Outremer was about to be wiped off the map and by the desire to retake Jerusalem. Kings from England, the Holy Roman Empire, and France as well as other powerful princes answered the call. When they arrived in the last remaining Christian outposts in the Middle East, they quickly fell to squabbling with each other and the aristocracy of Outremer. As a result, the Christians were able to conquer the island of Cyprus and the coastline of the Holy Land but were unable to move farther inland. Eventually, Richard I of England, known in popular stories as Richard the Lionhearted, negotiated a treaty with Saladin that left Jerusalem under Muslim control but allowed Christian pilgrims to freely visit the city. Both Saladin and Richard were praised as examples of chivalric virtue in Europe and heroes of their respective religions. But this was one of the last successes the crusaders were to have in the Holy Land.

The First (1096-1099), Second (1147-1149), and Third Crusades (1189-1192) profoundly altered the medieval landscape. The First Crusade’s success in capturing Jerusalem in 1099 and establishing Christian states in the Levant sparked a wave of religious fervor and territorial expansion. However, the Second Crusade’s failure to retake Edessa in 1147 and the Third Crusade’s inability to reclaim Jerusalem, following its loss to Saladin in 1187, exposed the fragility of the Crusader states. Despite these military setbacks, the Crusades facilitated cultural exchange, trade, and technological transfer between East and West. They also intensified Muslim-Christian animosity, fueled anti-Semitic violence, and reshaped European politics. The Crusades solidified the power of the papacy, contributed to the decline of feudalism, and spurred the growth of cities and nation-states. Key figures such as Richard the Lionheart, Frederick Barbarossa, and Saladin emerged as legendary leaders. The legacy of the Crusades extends beyond the medieval period, influencing colonialism, Orientalism, and modern conflicts in the Middle East.

Later Crusades

The Crusading movement continued beyond the Third Crusade, although enthusiasm waned significantly. Pope Innocent III, a powerful medieval pope, called for a new crusade in 1202, aiming to bypass the treacherous overland routes through Anatolia and the increasingly hostile Byzantine Empire, which was fraught with religious conflicts and accusations of betrayal. Instead, the crusaders commissioned ships from Italian cities to transport them directly to the Holy Land. However, the Venetian leader requested that they attack Zara, a Christian port city on the Dalmatian coast and a rival of Venice, in exchange for their transportation. This agreement enraged the pope, leading to the excommunication of the crusaders.

The crusaders then proceeded to Constantinople, where they became entangled in the Byzantine Empire’s internal politics and ultimately sacked the city after a failed attempt to install a pro-crusader emperor. This event marked a profound betrayal of Greek Christians and the ideals of the crusading movement, causing significant damage to relations between the Greek Orthodox and Catholic churches. The Catholics established the short-lived Latin Empire of Constantinople, but the consequences of this action were far-reaching.

In the following years, the focus of the crusades shifted to Egypt, a crucial base for controlling the Holy Land. Subsequent crusades became increasingly French and less successful in achieving their objectives. Louis IX, the French crusader-king, led the Seventh and Eighth Crusades against Muslim rulers in North Africa, ultimately dying there. The fall of Acre in 1291 marked the end of the Crusader States. The concept of crusading evolved, with popes declaring holy wars against non-Christians in the Baltic regions, heretics in France, and personal enemies in Italy. Crusaders expected privileges such as indulgences, protection of property, and relief from feudal dues. By the thirteenth century, crusading had become commonplace, with generations of families participating. However, the decline of papal power and the revival of royal authority in the fourteenth century led to a decrease in popularity. The rise of powerful Islamic kingdoms in the Middle East made controlling Jerusalem increasingly impractical, and European kings shifted their attention toward building nation-states and warring against their rivals.