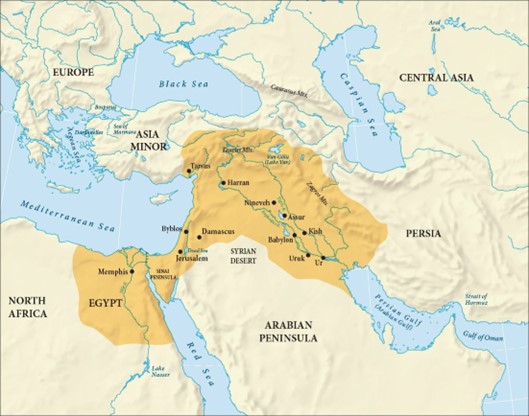

25 The Ancient Middle East

In the fourth millennium BCE, some of the earliest known great cities emerged in southern Mesopotamia, a region between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, known then as Sumer. The people who built these cities, the Sumerians, developed one of the earliest forms of writing, known as cuneiform, around 3400-3000 BCE. This writing system enabled them to record their literary works, laws, and business transactions, which continued to be studied and preserved by later Mesopotamian civilizations, even after the Sumerian language fell out of everyday use.

This region, now modern-day Iraq, benefited from fertile soil deposited by the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, which flowed from the Taurus Mountains to the Persian Gulf. However, the rivers’ unpredictable flooding created a need for cooperative irrigation projects, leading to the development of sophisticated water management systems. Agriculture began in Mesopotamia around 8000 BCE, and settlers started establishing themselves in southern Sumer around 5500 BCE. As the region became wetter and more suitable for agriculture, the Sumerian civilization flourished. By 4500 BCE, small villages were transformed into thriving urban centers, with Uruk becoming the first large city, boasting a population of around 50,000 by the end of the 4th millennium BCE. This rapid urbanization marked the beginning of Sumer’s rise as the earliest civilization in Mesopotamia, laying the groundwork for the development of subsequent cultures.

The fourth millennium BCE was a transformative period in Sumer, marked by groundbreaking technological innovations. One of the most significant advancements was the development of bronze, an alloy of tin and copper, which marked the beginning of the Bronze Age in Mesopotamia around 3300–3000 BCE. Bronze soon replaced stone as the primary material for tools and weapons, maintaining its dominance for nearly three millennia. Additionally, the ancient Sumerians developed pioneering agricultural tools, such as the plow and the wheel, and sophisticated irrigation systems that utilized channels, canals, and dikes to divert river water into fields. These advancements facilitated population growth, urbanization, and increased agricultural productivity.

In the realm of science, the Sumerians devised a complex mathematical system based on the numbers sixty, ten, and one. They also made a revolutionary invention: writing. The Sumerians created cuneiform, a script featuring wedge-shaped symbols that evolved into a phonetic system, where each symbol represented a syllable. They inscribed their laws, religious texts, and property transactions on durable clay tablets, which, once baked, became long-lasting records. These tablets documented commercial exchanges, including contracts, receipts, taxes, and payrolls. Cuneiform, the writing system developed by the Sumerians, was remarkably complex and enabled rulers to codify their laws and priests to preserve rituals and sacred stories, thereby facilitating economic growth and state formation.

The Sumerians believed in a multitude of powerful, supernatural beings, each associated with specific aspects of life and the natural world. These beings, known as dingir in Sumerian, were thought to inhabit the world alongside humans and were often linked to particular cities, regions, or natural phenomena. Each city had its own patron dingir, with whom the city felt a special connection and honored above others. For example, Uruk revered Inanna, the embodiment of fertility and sexual power; Nippur honored Enlil, the master of the air and storms; and Ur worshipped Sin, the personification of the moon’s cycles. This belief system recognized the complexity and diversity of the sacred realm, and the Sumerians built elaborate temple complexes to honor their dingir.

During the Early Dynastic Period (c. 2650 BCE–2400 BCE), powerful city-states emerged in Sumer, each ruled by a king who rose to power primarily through military conquest. Cities frequently clashed over valuable resources like farmland, water, and trade routes. To legitimize their authority, these rulers controlled the city’s religious institutions, often holding high-ranking priestly positions. For instance, in Ur, the king’s daughter served as the high priestess of the moon god Sin, the city’s patron deity.

The First Dynasty of Ur, which ruled during this period, was particularly prosperous, as evident in the elaborate beehive-shaped tombs of their rulers. These tombs contained precious goods like jewelry, musical instruments, and even the bodies of servants sacrificed to accompany their rulers in the afterlife. One notable example is the tomb of Pu-Abi, a woman of Ur who may have been a queen, buried with an elaborate headdress. The most legendary king of this era was Gilgamesh of Uruk, whose exploits were later immortalized in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Link to Learning

The Epic of Gilgamesh is one of the world’s earliest examples of epic literature. To understand this ancient tale, first written down in the form we know today around 2100 BCE, read the overview of the Epic of Gilgamesh (https://openstax.org/l/77gilgamesh) provided by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which has a notable collection of ancient Mesopotamian artifacts.

Life for ordinary people in ancient Mesopotamia was marked by hard work and simple living. Most people resided in rural areas, working as farmers or herders, and spent their days tending to crops, animals, and households. Women played a crucial role in managing the household, raising children, and assisting with agricultural tasks. Social hierarchy was strict, with nobles and priests holding significant power and influence, while commoners had limited access to education, healthcare, and social mobility. Despite these challenges, ordinary people found joy in festivals, storytelling, and community gatherings, which provided a sense of belonging.

Daily life was deeply influenced by the natural environment, with people relying on the Tigris and Euphrates rivers for water, transportation, and fertile soil. Homes were typically simple mud-brick structures, and it was common for multiple generations to live together in these dwellings. People wore basic clothing made from wool and linen, and their diets included staples such as bread, onions, garlic, and occasional meat. Economic transactions were primarily conducted through bartering, though the use of silver and copper as currency also played a role. Amidst the hardships, people found comfort in their religious beliefs, worshiping a pantheon of gods and goddesses who were believed to influence every aspect of life, from fertility to warfare.

Core Impact Skill: Perspective-Taking

As you explore the rise of Sumer and the early civilizations of Mesopotamia, take a moment to step into the lives of the people who built these cities. What would it feel like to be part of a growing urban center like Uruk, surrounded by mudbrick houses, massive temple complexes, and bustling markets? Imagine being a scribe learning cuneiform, a farmer managing unpredictable floods, or a priest performing rituals to honor your city’s patron deity.

Perspective taking helps you go beyond names and dates to ask deeper questions:

-

What might it have meant to worship a god like Inanna or Enlil and believe they directly shaped your city’s fate?

-

How would your daily life be shaped if you lived under Hammurabi’s laws—or if you were a woman managing a household in a society structured by strict social classes?

-

What would it feel like to witness the power of a king who claimed divine support, or to live through the fall of a city conquered by empire builders like Sargon?

By imagining the lives of ordinary people, rulers, scribes, soldiers, and priests, you develop a richer understanding of what made Mesopotamian society both innovative and deeply human. That’s the heart of perspective taking.

Early Empires

Around 2300 BCE, the era of independent Sumerian city-states came to an end. Sargon of Akkad, a powerful leader, conquered Sumer and unified Mesopotamia, creating one of the earliest known empires. The Akkadians, who settled in central Mesopotamia, adopted Sumerian culture and adapted cuneiform to their own Semitic language. Sargon’s empire extended from Sumer to northern Iraq, Syria, and southwestern Iran. Although the precise details of his rise to power are somewhat obscure, the Legend of Sargon, written about two centuries after his death, describes his humble beginnings and his ascent to greatness.

While Sargon’s empire lasted only a few generations, his conquests dramatically transformed politics in Mesopotamia. The era of independent city-states waned, and over the next few centuries, powerful Mesopotamian rulers built their own empires, often using the administrative techniques developed by Sargon as a model. For example, beginning about 2112 BCE, all Sumer was again united under the Third Dynasty of Ur. The most famous king of this dynasty was Ur-Nammu (c. 2150 BCE), renowned for his works of poetry as well as for the law code he published.

At its height, the Third Dynasty extended its control over both southern and northern Mesopotamia. But by the end of the third millennium, foreign invaders from the north, east, and west put tremendous pressure on the empire, and its rulers increased their military preparedness and even constructed a 170-mile fortification wall to keep them out. While these strategies were somewhat effective, they appear to have only postponed the inevitable as Amorites, Elamites, and other groups eventually poured in and raided cities across the land. By about 2004 BCE, the Third Dynasty had crumbled, as Ur was violently sacked by the invaders.

As Amorite tribes settled in Mesopotamia, they established prominent new cities such as Mari, Asshur, and Babylon, adopting much of the existing Sumerian culture. Babylon, in particular, emerged as a significant power under Amorite influence. Among the Amorite rulers, Hammurabi, who reigned in the early 18th century BCE, stands out as a transformative figure. As king of Babylon, Hammurabi expanded his domain by conquering rival cities and created a vast empire. To unify and govern his realm effectively, he launched major irrigation projects, built temples in key cities like Nippur, and enacted a comprehensive code of laws. He inscribed these laws on stone stelae, providing a clear guide for his subjects’ behavior. The Code of Hammurabi, which has survived through the millennia, offers a unique insight into Mesopotamian society and governance at that time.

Learn More

The Babylonian Empire reached its zenith under the leadership of Hammurabi, encompassing a vast territory that stretched from the upper Euphrates River, near modern-day Aleppo, to the Zagros Mountains in the east and the Persian Gulf in the south. However, this extensive empire began to crumble after Hammurabi’s death. His son, Samsu-iluna, faced opposition from the Kassites in the Zagros Mountains and the newly formed Sealand kingdom in the Persian Gulf region. As a result, the empire’s territorial control continued to wane, until, by the late sixteenth century BCE, under the reign of Samsu-ditana, only the small region surrounding Babylon remained. In this weakened state, the empire was vulnerable to attack, and the Hittites eventually sacked Babylon, marking the definitive end of Hammurabi’s dynasty.

The Hittites

The Hittites, an Indo-European-speaking people, emerged as a dominant force in Anatolia around 1600 BCE. They likely migrated to the region, assimilating with the local population and adopting their culture and religion. By 1650 BCE, the Hittites had established their capital at Hattusas and expanded their control across Anatolia and into Syria under King Mursilis. Their empire continued to grow, and they eventually set their sights on Babylon, which they conquered. However, Mursilis’s absence from Anatolia weakened his power, and he was assassinated upon his return. The Hittite Empire then faced internal strife, rebellion, and war, but by 1500 BCE, order was restored. The Hittite Empire experienced a resurgence under King Tudhaliyas I in 1420 BCE, marked by new imperial growth and expansion. By the mid-14th century BCE, under King Suppiluliumas I, the Hittites had become a dominant power in the Near East, rivaling New Kingdom Egypt.

Hittite society was distinctly different from that of the Babylonians. The empire consisted of only a few large cities, such as Hattusas, while most people resided in small rural villages or towns. Land was primarily held in common and worked by the community, with some exceptions for leased acreage. Initially, slavery was rare in Hittite society, but as the empire expanded and war captives increased, enslaved people became more numerous. The Hittites practiced chattel slavery, treating enslaved individuals as property that could be sold at will, often forcing them to work in agriculture to free citizens for military service.

Hittite religion was a blend of various traditions, including Mesopotamian influences. Divination rituals, such as studying animal organs and consulting female soothsayers, were adopted from Mesopotamia. The pantheon of celestial beings included the Arinna (a powerful feminine sacred being associated with the sun) and her consort, Tarhunna, who oversaw the government, rains, and war. The king, as high priest, performed sacred rites at major festivals like the New Year Festival, which determined the course of events for the coming year. The people were expected to participate in religious rituals at cult centers.

The Neo-Assyrian and Babylonian Empires

The Hittite Empire came to an end during the Late Bronze Age Collapse, a period of widespread upheaval that began around 1200 BCE. This era saw the downfall of kingdoms and empires across the region, from Greece to Mesopotamia, coinciding with devastating famine, disease, war, and mass migrations. The cause of this collapse remains a mystery, but its impact was profound, marking the end of an era and the beginning of a new one. By 1100 BCE, the region had entered the Iron Age, characterized by the adoption of iron tools and weapons, and the emergence of new, more advanced empires in the ancient Middle East.

In the 9th century BCE, Assyria reasserted its dominance over northern Mesopotamia, marking the beginning of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. This new era of Assyrian power was marked by a series of military conquests, beginning with the reign of Ashurnasirpal II. The Neo-Assyrian Empire expanded rapidly, absorbing numerous Aramaean kingdoms in Syria and eventually conquering Babylonia. By the end of Tiglath-Pileser III’s reign in 727 BCE, Assyria had become the supreme power in the Near East, its dominance unchallenged. Over the next several decades, successive Assyrian kings continued to expand their empire through military victories, ultimately reaching as far as Egypt, which was conquered by King Esarhaddon in 671 BCE. This achievement marked the zenith of Assyrian power, surpassing the territorial control of any previous empire in the region. However, Assyria’s dominance was short-lived, as two rising powers, Babylonia and Media, eventually challenged and overthrew Assyrian rule in the late 7th century BCE.

The Assyrian Empire was structured into four main hierarchical classes: the nobility, the professional class, the peasantry, and the enslaved. The nobility occupied the highest positions, managing large estates and receiving comprehensive educations to prepare for elite roles. Priests were vital in interpreting the will of sacred beings and maintaining the connection between the political center and the broader empire. The professional class comprised skilled workers like bankers, physicians, and merchants, each organized into guilds. The peasantry, the largest yet least documented class, consisted of poor farmers working under the higher classes. At the bottom were the enslaved, mainly war captives with minimal rights.

Above these classes was the king’s household, with the Assyrian king viewed as the earthly representative of divine beings. The king was expected to embody divine behavior, respond to omens, and defend order against chaos. During difficult times, the king might undergo ritual humiliation or even symbolically ‘die’ to appease the gods. The Neo-Assyrian Empire’s constant military campaigns required a well-trained and organized standing army, including charioteers, cavalry, and archers. All Assyrian men were expected to serve in the military, with the king as the official commander. The empire operated as a military state, excelling in both territorial expansion and maintaining control over its vassals.

During the Assyrian Empire’s expansion, Babylonia was reduced to a vassal state, meaning it had limited autonomy and was required to provide resources and military support to the empire. However, in 616 BCE, the Babylonian ruler Nabopolassar saw an opportunity to challenge Assyrian dominance during a period of weakness and launched an attack on the Assyrian capital of Asshur. Although the attack failed, it prompted the Median Empire, a recently unified kingdom in northwestern Iran, to launch its own attack on Assyria. The Median Empire had grown in power due to Assyria’s devastation of surrounding kingdoms. The combined forces of the Babylonians and Medes ultimately led to the downfall of Assyria. In 612 BCE, they destroyed the city of Nineveh, killing the Assyrian king, and captured other key cities. The remaining Assyrian forces fled west but were eventually defeated by 605 BCE, marking the end of the Assyrian Empire.

The victors divided the spoils, with the Median Empire controlling the eastern regions and expanding into central Anatolia, western Iran, and the southern Caucasus. The Babylonians, also known as the Neo-Babylonians, took control of the western portion of the former Assyrian Empire, including Mesopotamia, Syria, and the Phoenician ports. Under King Nebuchadnezzar II, they waged wars in Syria and the eastern Mediterranean to weaken Egypt’s power. In 601 BCE, Nebuchadnezzar attempted to invade Egypt but was repelled by strong resistance.

The Ancient Hebrews

The ancient Hebrews emerged around 1800 BCE in the Middle East, originating from the eastern Mediterranean region. They were a Semitic-speaking people who developed a distinct culture and identity. Initially organized into tribes, each with its own leader and territory, the Hebrews practiced pastoralism and developed complex social and religious norms. Archaeological evidence supports their migrations and early settlements, including the legendary journey of Abraham from Ur to Canaan.

As the Hebrews settled in Canaan, they developed a more complex society characterized by the emergence of cities and kingdoms. The period of the judges saw charismatic leaders guiding the Hebrews through crises, leading to the establishment of a monarchy. The reigns of Saul, David, and Solomon marked a significant period of state formation and cultural development, including the composition of sacred texts and a literary tradition. The Hebrews worshipped Yahweh, a deity believed to have chosen them as His special people, which was central to their identity.

Over time, the Hebrews’ identity evolved, especially after significant events like the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem by the Babylonians in 586 BCE and subsequent exile. The term “Jews” became more commonly used, especially after their return to Jerusalem and the rebuilding of the Temple under Persian rule. By this period, the fundamental principles of Judaism had taken shape. Jews were expected to worship only Yahweh, lead moral lives according to His laws, and follow the teachings of Moses. This included adhering to dietary restrictions, observing rituals like proper food preparation and Sabbath observance, treating others with respect, giving to charity, and upholding laws related to marriage and family.

The laws of Moses also addressed agricultural issues, reflecting the Hebrews’ origins as farming clans. For example, there were rules about harvesting and offering first fruits to Yahweh. The festival of Sukkot, a harvest celebration, involved building temporary shelters to commemorate the Hebrews’ agricultural past. However, as the Hebrews urbanized and adopted new occupations, these traditions became largely symbolic. In cities like Jerusalem, Jews found economic opportunities as artisans, traders, and merchants. As the city grew, their religion adapted to urban life, with the temple at its center.

The temple, completed around 515 BCE, was a hub of religious activity. It featured courtyards, altars, and a sacred inner sanctuary known as the Holy of Holies, where Yahweh was believed to reside. Priests oversaw various festivals and rituals, including animal sacrifices offered by worshippers seeking Yahweh’s favor. The temple played a vital role in Jewish life, serving as a unifying force and a symbol of their connection to Yahweh.

Link to Learning

Learn more about Jewish beliefs and practices by reading Dr. Mack’s chapter on Judaism in his book, Religions of the World: Introduction.