20 Ancient China

Although ancient China was not the first Asian civilization to cultivate agriculture and establish cities, it made significant contributions to human history. The region was home to some of the world’s earliest political dynasties, which laid the groundwork for China’s rich cultural heritage. Ancient China also developed written scripts, influential philosophical and religious traditions, and innovative technologies in architecture and metallurgy. The manufacture of bronze and iron tools, such as agricultural implements, weapons, chariots, and jewelry, demonstrates the advanced technological capabilities of ancient Chinese civilization.

Prehistoric China: A Land of Diversity and Adaptation

The arrival of early humans in China from Africa and western Asia occurred in waves, spanning hundreds of years, resulting in a diverse array of societies. These societies developed distinct languages, spiritual beliefs, and agricultural practices, shaped by their unique environments. The presence of human beings in China dates back over a million years, with evidence of Homo erectus, a precursor to modern humans, found in northern China. The well-known Peking Man, a subspecies of Homo erectus, is a notable example. Later, around 100,000 years ago, Homo sapiens emerged, and these early communities of hunter-gatherers migrated to northern China in pursuit of mammoths, elk, and moose.

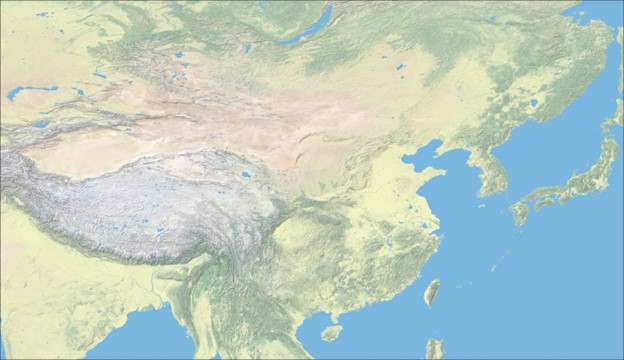

China’s vast and diverse geography, climate, and terrain reinforced regional variations in these early cultures. The country’s expansive territory, stretching over a thousand miles, encompasses a range of environments, including mountains, deserts, grasslands, high plateaus, and jungles. Early inhabitants of China adapted to their regional environments, leveraging advantages and addressing challenges to meet basic needs: food, shelter, and security. Most early cultures and later dynasties developed within a smaller area, centered around the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers, surrounded by outer regions like Manchuria, Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Tibet. These regional variations laid the groundwork for the rich cultural heritage of China.

The Yellow River, stretching over 3,395 miles, has played a crucial role in shaping Chinese civilization. The river’s fertile loess soil, a thick deposit of wind-blown sediment, has supported early agriculture and human settlement. However, the loess soil’s susceptibility to erosion has led to frequent changes in the river’s course, resulting in recurring floods and droughts that have affected the surrounding areas. The region’s limited rainfall, averaging twenty inches annually, exacerbates these cycles.

Archaeological sites near the Yellow River, such as Erlitou, reveal complex societies with advanced features like palaces, bronze vessels, and ancestor worship. These findings have sparked debate about the existence of the Xia dynasty, a legendary kingdom said to have been founded by the Great Yu. While no written records from the Xia have been found, references to it appear in later texts.

The Shang Dynasty: A Sophisticated Bronze Age Civilization

The Shang dynasty, the first Chinese dynasty with solid evidence, created a sophisticated Bronze Age civilization that significantly impacted Chinese history. Initially considered mythical, the Shang dynasty was verified through the discovery of inscribed turtle shells and “oracle bones,” which provide valuable insights into China’s first dynasty.

Religion and ritual were the foundation of Shang society, with kings serving as high priests worshiping their ancestors and the supreme deity Di. Shang queens and princesses played significant roles in politics and warfare, with notable women like General Fu Hao leading large armies. Aristocratic women also served as priests in the royal ancestral cult, highlighting the theocratic dimension of the Shang dynasty, where kings claimed exclusive rights to act as intermediaries between their subjects and the spirit world.

The Shang kings solidified their authority through rituals of ancestor worship and bone divination, adapted from the Erlitou culture. They developed a logographic script, where characters represented words and ideas, and used it for various purposes like record-keeping, calendar-making, and knowledge preservation. This script, passed down to future dynasties, made literacy exclusive to elites, requiring memorization of hundreds of symbols.

To further solidify their royal role, the Shang kings built palaces, temples, and altars in their capital cities, supported by artisans crafting various goods. They constructed enormous tombs for royals and nobility, demonstrating their ability to organize labor and resources on a vast scale. Fu Hao’s tomb, while smaller than others, was dug twenty-five feet deep and held sixteen human sacrifices and hundreds of bronze weapons, mirrors, and other items made from bone, jade, ivory, and stone.

The Shang’s invention of writing enabled them to command vast resources for two centuries. They developed the organizational capacity to mine metal ores, transport them to foundries, and create massive bronze vessels. Artisans wove silk into cloth, and ten thousand workers built city walls around Zhengzhou.

The Shang became China’s first dynasty due to their military prowess, expanding their power through conquest. They built a large territorial state controlled by a noble warrior class, spanning Henan, Anhui, Shandong, Hebei, and Shanxi provinces. The Shang used bronze weapons and horse-drawn chariots to raid neighboring cultures, distributing spoils to vassals and making enemies into allies. They also organized royal hunts to hone their skills, showcasing their aristocratic and militaristic culture.

The Zhou Dynasty’s Rise to Power

The Zhou dynasty, which emerged in 1045 BCE, had a complex relationship with its predecessor, the Shang dynasty. Originating from a distinct homeland in today’s Shaanxi province, the Zhou people initially became vassals of the Shang kings, defending them against rivals like the Qiang. However, the Zhou eventually rose up against the Shang, claiming they had become despotic and mismanaged China’s resources. Led by King Wu, the Zhou defeated the Shang in 1045/46 BCE, marking a significant turning point.

With advanced military technology, including chariots, bows, and bronze armor, the Zhou overthrew the Shang and established a new dynastic ruling house. The Zhou victory was recorded in Chinese classical texts as evidence of the “Mandate of Heaven,” which legitimized their rule and established a key concept in Chinese political ideology.

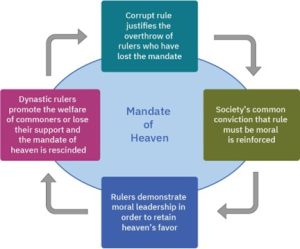

The Mandate of Heaven held that rulers must demonstrate morality and order to retain heaven’s favor and avoid losing their right to rule. This concept justified the overthrow of corrupt governments and emphasized the importance of moral leadership, support for agriculture, the arts, and the welfare of the common people. Natural disasters, social upheaval, and rebellions were seen as signs of a dynasty’s potential loss of the Mandate. This ideology had a lasting impact on Chinese political thought, shaping the understanding of dynastic cycles and the responsibilities of rulers.

The Zhou dynasty’s innovations had a profound and lasting impact on Chinese culture and politics. By breaking away from the Shang dynasty’s traditions, the Zhou established a new era of dynastic rule that emphasized the importance of heavenly mandate and cosmic balance in legitimizing their power. This marked a significant departure from the Shang’s focus on ancestor worship and divination. The concept of the Mandate of Heaven, which held that rulers were appointed by heaven to maintain harmony and order, became a core ideology that was passed down through successive dynasties, including non-Chinese ruling houses like the Mongols and Jurchen. This concept served two purposes: it provided a basis for political unity under a supreme sovereign, while also providing a moral justification for dissent against rulers who failed to uphold heaven’s mandate.

Dynastic Continuity

The Zhou dynasty can be divided into four main periods. The Western Zhou period lasted from 1046 to 771 BCE. The Eastern Zhou period, which spanned from 771 to 256 BCE, is further subdivided into two sub-periods: the Spring and Autumn period from 771 to 476 BCE, and the Warring States period from 475 to 221 BCE. During the Eastern Zhou, the Zhou kings’ power eroded, and outlying territories became autonomous, leading to the Warring States era, characterized by warfare between regional powers. The Warring States Era (475-221 BCE) marked a significant shift in warfare, transforming ancient China’s military landscape. Gone were the chivalrous codes of conduct, replaced by brutal efficiency and massive conscript armies. New technologies like the crossbow and iron armor made traditional cavalry and chariots obsolete. Military success now depended on discipline, strategy, and logistics. Treatises on deception and siege craft proliferated, and warfare became a catalyst for change.

Despite the chaos, some changes brought benefits. Common farmers gained rights and pressured rulers for land improvements. Iron technology advanced, boosting agricultural productivity and economic growth. Trade flourished, with increased coinage and social mobility. Aristocratic families fell, while new gentry and merchant classes rose. Merit became the path to success, and lower-level aristocrats found new roles as bureaucrats.

This period also saw the flourishing of literature and philosophy, known as the Hundred Schools of Thought (770-221 BCE), which inspired the study of military arts, diplomacy, and political intrigue, as well as morality and ethics. Philosophers like Mozi and Sunzi (author of The Art of War) created rival traditions, contributing to debates on morality, war, government, technology, and law, and informing a growing class of administrators and military strategists competing for patronage.

During this period, Chinese civilization experienced rapid growth and sophistication. Rulers sought to increase revenue, population, and agricultural productivity through innovative techniques like marsh drainage and new forms of currency, such as silk bolts. The era also saw the emergence of vibrant art forms, including music and dance, with states like Chu and Zheng gaining fame for their unique styles. The Book of Songs preserved popular hymns, showcasing the diverse intellectual traditions and cultural forms that shaped ancient Chinese politics, education, and art.

Confucianism, founded by Kong Fuzi (Confucius), was a prominent philosophical system that influenced morality, governance, and social relations in China and later spread to Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. Confucius, born around 551 BCE, taught in the state of Lu, and his descendants and disciples compiled his teachings in The Analects. Later scholars, like Mengzi, built upon Confucius’ ideas, attracting students and advising rulers.

Confucianism emphasizes virtuous leadership rooted in moral living, ritual practice, and commitment to one’s duties. Confucian texts, such as the Book of Documents, promote literacy, critical thinking, and humility as essential qualities of a well-ordered society. Confucius placed strong importance on family relationships as the foundation of social order, identifying five key bonds: king and subject, father and son, husband and wife, elder and younger siblings, and friends. Each bond called for obedience and honor—except between friends, who should treat each other with mutual respect. Confucian thought required rulers to embody ren by showing generosity and empathy toward those they governed, thereby maintaining harmony throughout society.

Later Confucian teachers, such as Xun Kuang (Xunzi), responded to the violence of the Warring States period by emphasizing the need for rigorous self-cultivation and discipline to overcome humanity’s base impulses. This led to a focus on internal self-improvement and concern for the well-being of others and society among devout Confucians. Meanwhile, Zhou kings continued to perform rites honoring their royal ancestors, but also increasingly utilized written works to enhance their prestige and power. Notably, the Yijing (The Book of Changes) emerged as a new system of divination, later becoming a foundational text that shaped Confucian thought and values.

Link to Learning

Learn more about Confucian beliefs and practices by reading Dr. Mack’s chapter on Confucianism in his book, Religions of the World: Introduction.

Daoism, a mystical indigenous religion, emerged during the Zhou era, emphasizing harmony with nature and balance within oneself. Its teachings, compiled in texts like the Tao Te Ching and Zhuangzi, encouraged individuals to appreciate nature, explore mystic rituals, and recognize their place in the vast universe. At the heart of Daoism lies the concept of the Dao, or “the Way,” an underlying force that shapes and infuses all aspects of life, guiding individuals towards a path of natural harmony and balance. Daoists introduced the concept of wuwei, or non-action, suggesting that the best governance was minimal interference in people’s lives.

Link to Learning

Learn more about Daoist beliefs and practices by reading Dr. Mack’s chapter on Daoism in his book, Religions of the World: Introduction.

In contrast, Legalism focused on accumulating power through a strict legal code, rewards, and punishments. Legalists like Han Feizi believed that a strong government required a rich country and a powerful army, and that morality was less important than enforcement and order. They argued that a written legal code, backed by a system of rewards and punishments, was the key to maintaining power and control.

While Daoism and Legalism differed significantly, they shared a common framework that shaped Chinese thought and culture. Daoism encouraged individual balance and harmony with nature, while Legalism prioritized power and control. This era is considered an “axial age” because of the significant contributions these schools made to the development of Chinese civilization and the world.

Core Impact Skill — Intercultural Competence

As you explore the rise of Chinese philosophy during the Zhou Dynasty and the Warring States period, take a moment to appreciate how early thinkers shaped one of the most enduring cultural and political traditions in world history. Confucianism, founded by Kong Fuzi (Confucius) in the 6th century BCE, emphasized moral leadership, social order, and the importance of duty in personal and political life. Confucian ideas spread widely—first through the teachings of disciples like Mengzi, and later across East Asia to Korea, Vietnam, and Japan—leaving a lasting imprint on both governance and daily life. Other schools of thought also emerged: Daoism, with its reverence for nature and cosmic harmony, and Legalism, with its insistence on strict law and centralized control.

Intercultural competence means recognizing that these diverse traditions responded to the same cultural challenges in profoundly different ways. Confucius believed that rulers should lead by example, embodying ren—compassion and humanity—and maintaining harmony through ritual, education, and respect for hierarchical relationships. Daoists instead urged followers to seek balance with the natural world and embrace the Dao, or “Way,” by practicing wuwei (non-action). Legalists such as Han Feizi rejected morality in favor of order, arguing that only strict laws and harsh punishments could ensure stability. Despite their differences, all three systems offered answers to the social upheaval of their time and shaped the development of Chinese society.

-

How did Confucianism encourage rulers to take the needs and perspectives of others into account?

-

What do Daoist ideas about harmony and wuwei suggest about how people should relate to the world around them?

-

How did Legalism’s emphasis on law and order reflect a different cultural response to the challenges of governing?

By studying the teachings of Confucius, Daoist sages, and Legalist scholars, we develop a deeper understanding of how people from different times and places have approached power, virtue, and community. That’s the heart of intercultural competence.

The Rise of Qin: A Turning Point in Chinese History

During the Warring States period, the state of Qin capitalized on economic and social changes by embracing Legalist reforms, which emphasized power and expansion. The arrival of Lord Shang (c. 390-338 BCE), a migrant from a rival territory, marked a significant turning point. As prime minister from approximately 356 to 338 BCE, he introduced Legalist ideas that dominated Qin’s elite thinking.

Initially, Qin was a marginal state on the western border of the Zhou lands, responsible for defending the borderlands and raising horses. Its peripheral location allowed for trade with central Asian peoples, fostering a militaristic culture and experienced army. To compensate for initial disadvantages, Qin leaders wisely recruited immigrant talent, adopted new governance techniques, and centralized rule through appointed officials. Under Lord Shang’s guidance (356-338 BCE), Qin scorned tradition, introducing new legal codes, standardized weights and measures, and a merit-based system for administrators. These changes created an obedient populace, increased agricultural productivity, and filled the state’s coffers.

Qin’s increasing power eventually led to the defeat of its rivals, paving the way for King Ying Zheng’s (259-210 BCE) triumph. In 221 BCE, he proclaimed himself Qin Shi Huang, or Shihuangdi, meaning “the first emperor,” marking the beginning of imperial China. He unified northern China by standardizing writing, currency, and laws, creating a centralized state. Under Shihuangdi’s rule, the tenets of Legalism fostered unity as the emperor standardized the writing system, coins, and the law throughout northern China. To consolidate power, defeated aristocratic families were forcibly relocated to the new capital, and appointed officials governed on behalf of the emperor, replacing the traditional feudal system. The emperor closely monitored officials’ performance, punishing those who failed and rewarding those who succeeded, ensuring strict control over his vast territories.

An 18th century painting of Qin Shi Huang

An 18th century painting of Qin Shi Huang

(attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

Qin militarism expanded Chinese territory, reaching the Ordos Desert in the northwest and modern-day Vietnam in the south. This marked the first Chinese claim to the region. The need for defense led to new infrastructure, including fortified towns and thousands of miles of roads. The Qin built the Great Wall to guard against northern nomadic tribes, a pattern followed by successive Chinese empires. (The current Great Wall of China was built during the Ming dynasty in the 14th-17th centuries CE.)

Shihuangdi’s reign also featured the creation of the Terracotta Army, thousands of life-sized clay soldiers and horses. The emperor’s paranoia and desire for immortality led to the construction of an enormous secret tomb, filled with clay replicas of his palace, army, and servants. Labor for projects like the Great Wall and Terracotta Army came from commoners as a form of tax or requirement under Qin law. Penalties for violating the criminal code were severe, including forced labor, banishment, slavery, or death.

The Fall of Qin and the Rise of Han

The Qin Empire rapidly disintegrated following Emperor Shihuangdi’s death in 210 BCE. A royal court conspiracy led by one of his sons resulted in the tragic demise of his rightful heir, a loyal general, and a talented chancellor. The Legalist philosophy, which had initially strengthened the Qin, now contributed to its fragility. The harsh laws and direct rule that had maintained imperial power sparked revolts by generals and noble families seeking a return to the aristocratic feudal system of the Zhou era.

The armies of Qin’s second emperor were ultimately defeated by Liu Bang, a commoner who rose to become Emperor Gaozu of the newly established Han dynasty. The early Han emperors deliberately distanced themselves from Shihuangdi’s legacy by reducing taxes and alleviating burdens on the common people. However, they built upon the Qin’s imperial framework, adopting uniform laws, consistent weights and measurements, a centralized bureaucracy, and a focus on expansionism to protect against northern “barbarians.” This foundation enabled the Han dynasty to achieve greatness.

The Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) was a defining era in Chinese history, known for its political, economic, and cultural achievements. Founded by Liu Bang, who became Emperor Gaozu, the Han Dynasty solidified the foundations of the imperial system and expanded China’s territory significantly. One of the most notable emperors of this period was Emperor Wu Di, who reigned from 141 to 87 BCE. His reign is remembered for extensive military campaigns that expanded China’s borders and established the Han Dynasty as a major power in East Asia. Wu Di also played a key role in promoting Confucianism as the state ideology, which profoundly influenced Chinese society and governance.

During the Han Dynasty, the development of the Silk Road became a significant factor in the empire’s prosperity. The Silk Road was not a single road but a network of trade routes that connected China to Central Asia, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean. The route facilitated the exchange of goods, including silk, spices, precious metals, and textiles, as well as ideas, technology, and culture. Zhang Qian, a diplomat sent by Emperor Wu in 138 BCE, is credited with opening up these trade routes, which had a profound impact on China’s economic and cultural interactions with distant regions. The Silk Road also played a crucial role in spreading Buddhism from India to China, influencing Chinese philosophy, art, and society.

Under the leadership of the Han Dynasty, scholars and innovators made significant advances in various fields, including science, technology, and literature. Pioneering thinkers developed sophisticated methods in astronomy and mathematics, introducing concepts such as the decimal system and advancements in calendar-making. In technology, the Han Dynasty saw the creation of inventions like the seismograph, which could detect earthquakes, and the development of paper-making techniques that revolutionized record-keeping and literature. Literature flourished with the compilation of historical texts and the rise of classical poetry, enriching Chinese cultural heritage. This period also witnessed breakthroughs in medicine, with texts like the Huangdi Neijing laying the groundwork for traditional Chinese medicine. These achievements reflect the vibrant intellectual and creative spirit that characterized the Han Dynasty, contributing to its lasting legacy in Chinese history.

Lasting Significance

Ancient Chinese history spans over 3,000 years, beginning with the Xia Dynasty around 2100 BCE and concluding with the fall of the Han Dynasty in 220 CE. This extensive period was marked by profound developments in politics, philosophy, art, and science, driven by human ingenuity and innovation. The Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE) introduced the “Mandate of Heaven,” a concept that justified imperial rule by divine approval. The Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE) made a pivotal impact by unifying China for the first time, establishing a centralized state with standardized systems and practices. The Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) is noted for its exceptional achievements across various domains. This era saw the establishment of the Silk Road, a network of trade routes that facilitated economic and cultural exchanges between China and distant regions. Confucianism emerged as a dominant philosophical framework, profoundly influencing Chinese values and thought. During this period, China experienced significant technological and scientific advancements, including the invention of paper, the compass, and gunpowder. These innovations revolutionized communication, navigation, and warfare.

Understanding ancient Chinese history is important because it laid the foundation for China’s enduring identity and cultural heritage. The development of unique philosophical systems, such as Confucianism and Daoism, provided a framework for governance, ethics, and social relationships that influenced not only China but also neighboring regions. Technological and scientific advancements, including paper-making, the compass, and gunpowder, played a pivotal role in shaping global history by transforming communication, navigation, and military strategies. Additionally, the establishment of the Silk Road facilitated significant economic and cultural exchanges between China and distant civilizations, integrating China into a broader global network. Overall, these achievements established China as a major world power and contributed to its rich and complex historical legacy that continues to resonate today.