19 Ancient Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asia

In the ancient world, Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asia stood out for their unique cultural exchange with the broader world. Through trade, religion, and diplomacy, Korea and Japan borrowed and adapted elements from Chinese civilization, but also significantly influenced each other. Similarly, Southeast Asia’s ties with India played a crucial role in shaping the region’s cultural development. As small cities and agrarian villages evolved into trade-post empires with monumental architecture, these regions formed their own distinct systems. For instance, Buddhist missionaries traveled from India along the Silk Roads, and pilgrims visited temples to study and bring back new ideas to convert their native cultures. However, upon arrival, Buddhism transformed into hundreds of new sects and interpretations of the path to enlightenment, blending with local customs and beliefs.

Ancient Korea

The first humans arrived in Korea around 30,000 years ago. The peninsula’s hilly terrain and northern mountains created a natural barrier with Manchuria. Important rivers include the Daedong, Han, and Yalu. The Korean peninsula was home to small tribes, cultures, and communities that exchanged ideas and goods with the Chinese and Inner Asian Steppe peoples like the Xiongnu. Ethnicity in ancient Korea was fluid, with groups borrowing from each other’s cultures and being absorbed and transformed by conquest.

In 108 BCE, the Han dynasty invaded northern Korea and established four garrisons to suppress the Xiongnu. This led to increased cultural exchange and the adoption of Chinese culture, including coins, seals, artwork, and building techniques, by Korean societies.

By the 1st century CE, notable Korean states like Joseon, Goguryeo, and Buyeo had emerged. These societies traded and sometimes raided Chinese settlements, forging their own war bands and strengthening their power. However, with the collapse of the Han dynasty in 220 CE, these Korean societies lost a valuable partner and source of resources, marking a significant turning point in their development. Thus, in the 3rd to 4th centuries CE, the Korean peninsula underwent significant changes. The continued decline of Chinese power led to an influx of refugees from China that accelerated state-building in Korea, marking the beginning of the Three Kingdoms era (313-668 CE). The three kingdoms – Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla – emerged, with Chinese immigrants bringing knowledge of political practices that strengthened elite rule and transformed them into kings.

As Chinese writing spread throughout Korea, literacy became a valuable skill, essential for studying Confucian texts and Buddhist sutras. Many Koreans traveled to China as apprentices, shaping early Korean culture and society. This exchange had a profound impact on Korean thought and customs, as Chinese ideas and practices were adapted and incorporated into Korean tradition. The adoption of Chinese writing also facilitated the development of a native Korean writing system, allowing for the expression of unique Korean ideas and perspectives. Moreover, the spread of literacy enabled the growth of a educated elite, who played a crucial role in shaping Korean politics and culture. As a result, Korean society became more complex and stratified, with a clear distinction between the literate elite and the illiterate masses.

Baekje emerged from Manchuria in 369, establishing a Chinese-style bureaucracy, maritime trade, and adopting Chinese culture. Initially, Baekje was a vassal state of Goguryeo, but it sought to assert its independence. However, Baekje’s expansion was halted when it was defeated by Goguryeo in 475, during the reign of Baekje’s King Gaero. This defeat led to Baekje’s renewed subjugation to Goguryeo. Seeking to break free from Goguryeo’s dominance, King Gaero formed an alliance with Silla, urging them to join forces against their common overlord, Goguryeo. This alliance marked the beginning of a complex web of relationships between the three kingdoms, with each seeking to assert its dominance over the others.

Silla, the smallest kingdom, emerged dominant under powerful families who adopted Chinese models. Queen Seondeok, who ruled Silla from 632 to 647 CE, was a visionary leader who played a crucial role in shaping the kingdom’s future. She was the first female ruler of Silla and ascended to the throne during a time of great turmoil, with rival kingdoms Goguryeo and Baekje threatening Silla’s borders. Undaunted, Queen Seondeok forged an alliance with the Tang Dynasty of China, leveraging their military might to counterbalance the power of Goguryeo and Baekje. Her diplomatic prowess and strategic thinking enabled Silla to emerge victorious, paving the way for the kingdom’s eventual unification of the peninsula. Moreover, Queen Seondeok was a patron of Buddhism and the arts, encouraging the development of Korean culture and learning. Her legacy as a wise and effective leader has endured for centuries, inspiring generations of Koreans and cementing her place in Korean history.

During this period, Korean artisans learned celadon ceramic production from China, contributing to a thriving trade network. Korean ceramics became renowned for their beauty and quality, with celadon pieces highly prized by Chinese and Japanese collectors. The development of ceramics also facilitated the growth of a thriving artisan class, with skilled craftsmen producing works of art that reflected Korean aesthetic sensibilities. Moreover, the trade network established during this period enabled the exchange of ideas and technologies, further enriching Korean culture and society. As a result, Korean civilization continued to evolve and flourish, laying the groundwork for the vibrant culture and society that exists today

Ancient Japan

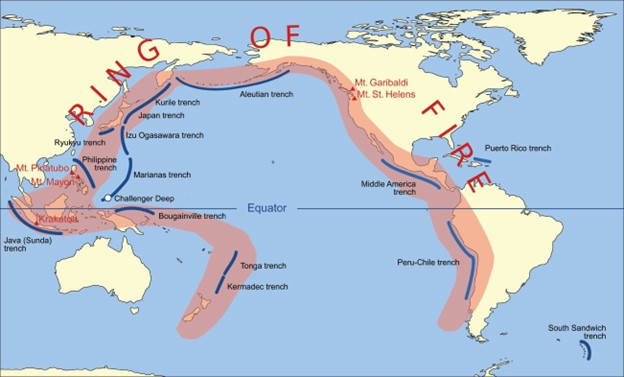

Just as in Korea, geography played a crucial role in shaping Japan’s early development and history. Japan’s terrain is comprised of four main islands: Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu. Honshu, the largest island, is home to Tokyo and the majority of Japan’s population. The islands of Okinawa and numerous smaller ones scattered across the Pacific are also part of Japan. However, the story of ancient Japan primarily revolves around the main islands, the Inland Sea of Japan, the country’s vast mountain ranges, and a few fertile plains nourished by monsoon rains that support agriculture. The formation of Japan’s main islands and their geographical features is largely attributed to the Ring of Fire, a zone of intense seismic and volcanic activity encircling the Pacific Ocean. This region has been responsible for numerous earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and tsunamis throughout Japan’s history, both in ancient times and in recent years.

Japan’s prehistoric era is divided into two periods: the Jōmon (14,500-300 BCE) and Yayoi (300 BCE-300 CE). During Jōmon, hunter-gatherer societies thrived, while Yayoi marked the emergence of agricultural communities. These early groups didn’t possess a modern “Japanese” identity, but their migration, settlement, and practices shaped the main islands’ culture. The Jōmon and Yayoi peoples adapted uniquely to their environments, developing distinct cultures and ways of life that still influence modern Japanese culture. The Jōmon period saw the development of pottery and tool-making, while the Yayoi period introduced new technologies like metalworking and weaving. These innovations laid the groundwork for Japan’s future cultural and technological advancements.

The Yayoi period saw the introduction of agriculture, leading to population growth and the development of storehouses, domesticated animals, and engineered landscapes. Queen Himiko (189-248 CE) was a notable female ruler who wielded significant spiritual power and engaged in warfare. The Yayoi period also saw significant cultural and political changes, including the emergence of a complex societal hierarchy. Aristocratic families, merchants, skilled divers and fishers, farmers, and commoners all played important roles in Yayoi society. The Yayoi people developed a rich cultural heritage, including intricate bronze work and ceremonial rituals. Their legacy can be seen in the modern Japanese culture, which still reflects the influences of these early periods.

The Yamato era (3rd century CE) marked a significant shift in Japan’s political landscape. Yamato kings consolidated power through alliances, trade, and ceremonies, while women maintained influence through sorcery and spiritual practices. As the Yamato rulers sought to legitimize their power and connect with continental culture, they adopted Buddhism, which had been introduced to Japan from Korea and China. The Yamato rulers solidified power through control of tombs and burial rituals, leading to the creation of capital cities, law codes, and centralized power. They also developed a system of writing, using Chinese characters to record laws, histories, and myths. As Buddhism took hold, Japanese leaders also began to adopt Confucianism, a philosophy emphasizing moral values, social hierarchy, and governance, which complemented Buddhism’s spiritual focus. In 604 CE, Prince Shotoku introduced his “Seventeen Article Constitution,” a seminal document that emphasized Confucian values, social harmony, and imperial authority.

Link to Learning

Prince Shotoku’s “Seventeen Article Constitution” was an effort to reform the Japanese state along the lines of the Chinese imperial model. Read the translated law codes (https://openstax.org/l/77LawCodes) at Columbia University’s Asia for Educators site.

Religion played a significant role in ancient Japan, with Shintoism emerging as the indigenous faith. Shintoism emphasized the worship of kami, or spirits, believed to inhabit natural phenomena, ancestors, and sacred objects. Shrines and rituals honored these kami, seeking their blessings and protection. As Buddhism arrived in Japan from Korea and China in the 6th century CE, it gradually blended with Shintoism, forming a unique syncretic tradition. Buddhist temples and shrines coexisted, with many Shinto kami being reinterpreted as Buddhist deities. The Yamato rulers embraced Buddhism, seeing it as a means to legitimize their power and connect with continental culture. Over time, Shintoism and Buddhism evolved together, influencing art, literature, and daily life. This religious fusion shaped Japan’s distinct spiritual identity, with Shintoism’s emphasis on nature and tradition complementing Buddhism’s focus on compassion and enlightenment.

For ordinary Japanese, life during the Yamato era was marked by hard work and simplicity. Most people lived in small villages, working as farmers, artisans, or laborers. Daily life revolved around agriculture, with people rising early to tend to crops, irrigate fields, and harvest food. Homes were simple, made of wood or thatch, with earthen floors and tiled roofs. People wore basic clothing made of hemp or cotton, and lived on a diet of rice, millet, and vegetables. Social hierarchy was strict, with aristocrats and officials holding power over commoners. Despite this, village communities were tight-knit, with shared rituals, festivals, and ceremonies bringing people together. Buddhism and Shintoism influenced daily life, with people seeking spiritual guidance from local shrines and temples. While life was not easy, ordinary Japanese found joy in nature, community, and the simple pleasures of everyday life.

The Yamato rulers expanded their power across western Honshu and northern Kyushu, showcasing wealth and organizational skills through laborers and artisans. They issued law codes, emphasizing Chinese-inspired law, bureaucracy, and Confucian values. Later legal codes organized monasteries, established a judiciary, and managed advisor-vassal relations, laying groundwork for Japan’s cultural and political evolution. The Yamato rulers also developed a complex system of mythology, emphasizing their divine right to rule. By adopting Chinese imperial statecraft, they reinforced their power with mythology, regalia, and divine status, eventually becoming emperors. This marked the beginning of Japan’s imperial system, which would endure for centuries.

Beyond the Yamato realm, a distinct group emerged from the early Jōmon foragers, resisting Yayoi agriculture and adopting unique spiritual beliefs. They maintained connections with northern Asian cultures, while the Japanese imperial courts strengthened ties with China’s Tang dynasty. Relations between the northern people (later called Emishi) and southern courts deteriorated, but the Emishi survived through warfare, migration, and evasion until the late 9th century, when they were subdued by southern Japanese culture. The Emishi developed a distinct culture, blending Jōmon and northern Asian influences. They practiced hunting, gathering, and small-scale agriculture, and maintained a strong spiritual connection to their environment. Despite their eventual subjugation, the Emishi left a lasting legacy in Japan’s cultural heritage.

Southeast Asia

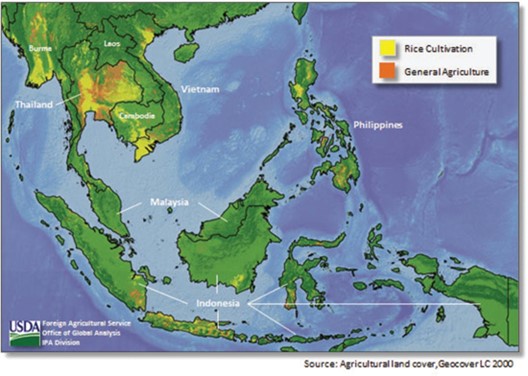

Southeast Asia, a vast region in subtropical Asia, encompasses thousands of Pacific islands and countries such as Brunei, Burma, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia. Historically, travel within this area was easier by sea than by land, with sparse populations and isolated communities scattered across forests and mountains. However, sea lanes facilitated early engagement with other cultures. Communities in Southeast Asia initially settled along coastlines, rivers, and lakes. As in India, early agriculture was driven by monsoon seasons, with farmers developing rainwater tanks and rice paddy cultivation. Slash-and-burn agriculture led to population fluidity, as people migrated after soil exhaustion.

Despite its vast territory and diverse climates, Southeast Asia shares commonalities that make it a distinct geographic and cultural zone. Its location between India and China led to the development of royal courts that borrowed foreign traditions, created trading-post empires, and asserted control over farmers and fishers. The region’s geography and climate made sailing a universal craft, with monsoon winds facilitating trade and cultural exchange between India and Southeast Asia. Merchants and missionaries transplanted customs, religion, and art, while residents enjoyed a rich marketplace of ideas, goods, and cultures from an early stage in world history.

The influx of foreign ideas played a crucial role in shaping Southeast Asian societies, but local communities selectively adapted and preserved their indigenous customs. A notable example is the emphasis on the individual family, a common thread across many Southeast Asian societies, differing from the emphasis on extended families and clans in India and China. Additionally, peasant communities in Southeast Asia generally accorded women higher status than their counterparts in China, where stricter Confucian values prevailed. This cultural nuance highlights the agency of local communities in adapting foreign influences to suit their unique social contexts.

While much of Southeast Asia faced west toward India as the center of trade, culture, and religion, the area near today’s Vietnam fell within the orbit of China’s cultural sphere emanating from the east. Vietnam’s natural geography created three distinct zones that shaped the country’s evolution: the Red River delta in the north, the Mekong River delta in the south, and a narrow land bridge along the coast connecting the two. Humans practicing wet-field rice agriculture developed settlements in the northern zone around 2500 BCE, and a millennium later, there is evidence of bronze-making. The Dong Son culture (c. 600 BCE-200 CE) made a notable contribution to world history with its remarkable bronze drums decorated with cords and animal images. These drums have been found across Southeast Asia.

Early Vietnamese groups spoke multiple languages and were divided into numerous small polities, kingdoms, tribal clans, and autonomous villages. There was no successful drive to centralize power under a unified dynasty in Vietnam’s prehistory. Vietnam’s prehistoric record shows that chiefdoms grew larger around 258 BCE, with the rulers of Au Lac constructing an impressive capital near today’s Hanoi. Later, Au Lac was conquered by Nam Viet, an offshoot of China’s Qin dynasty, and the area was later retaken by the Han dynasty. In 40 CE, Han control faced resistance from two rebellious daughters of a Vietnamese general, Trung Trac and Trung Nhi, who launched an uprising that briefly succeeded before being squashed. Their legacy became a source of Vietnamese nationalist pride and rejection of outside encroachment.

The Trung sisters’ uprising in 40 CE marked a pivotal moment in the history of northern Vietnam, as the region came under the direct governance of the Chinese Han dynasty. Over time, the Han rulers adopted local customs, leading to a blending of cultures that would shape the region’s identity. The Red River delta’s strategic importance to maritime trade in Southeast Asia ensured Chinese dominance for centuries, with the Han dynasty establishing the province of Jiaozhi to administer the region. Despite periodic rebellions, including the uprising led by Ly Nam De in 544 CE, the Sui and Tang dynasties reasserted control, solidifying Chinese influence. This period of governance had a lasting impact on the region’s culture and politics, with Confucianism and Buddhism becoming integral to Vietnamese society.

Core Impact Skill — Intercultural Competence

As you explore the early history of Vietnam, consider how cultural identity formed not only through resistance but also through interaction and adaptation. The Trung sisters’ uprising in 40 CE stands as a powerful symbol of Vietnamese defiance against Chinese Han rule, which had recently brought the region under direct imperial control. Although the rebellion was ultimately suppressed, it marked the beginning of a long and complex relationship between Vietnam and China, shaped by both conflict and cultural exchange. Over the following centuries, Chinese rulers governed the Red River delta through the province of Jiaozhi, enforcing political control while gradually adopting local customs and rituals.

Intercultural competence means recognizing that domination does not erase identity—and that cultural blending can shape new forms of society. Even as Chinese dynasties like the Sui and Tang reasserted authority after periodic uprisings, including that of Ly Nam De in 544 CE, the Vietnamese people preserved and adapted their traditions. Confucianism and Buddhism, introduced during Chinese rule, took root in local culture, influencing education, governance, and spiritual life. Maritime trade and local autonomy also helped shape a uniquely Vietnamese identity, one forged in the tension between external rule and internal continuity.

-

How did the Trung sisters’ rebellion express a distinct Vietnamese cultural identity in the face of foreign control?

-

What does the persistence of Confucianism and Buddhism in Vietnam reveal about cultural exchange under Chinese governance?

-

How did the geography of the Red River delta shape both Chinese interest in the region and Vietnamese responses to imperial rule?

By examining the history of early Vietnam through both resistance and adaptation, we better understand how cultures evolve under pressure—and how intercultural interactions can shape lasting legacies. That’s the heart of intercultural competence.

In contrast, the kingdom of Champa, located farther south, developed a distinct culture shaped by maritime trade and cultural exchange with India and other regions. The Cham people, who settled in the area around 500 BCE, engaged in extensive trade networks that spanned Asia, with their ports serving as key hubs for the exchange of goods like silk, spices, and precious stones. Women played significant roles in Cham society, including in trade and religion, with the worship of female deities like Po Nagar prevalent. The Cham people adopted an Indian-inspired script and incorporated Indian deities like Shiva into their pantheon, while also maintaining indigenous spiritual practices. This cultural synthesis resulted in a unique social structure and cultural identity, with the Cham kingdom reaching its zenith during the reign of King Bhadravarman I in the 4th century CE.

The Mekong River delta, home to the Khmer people, shared cultural and trade connections with Champa. The Khmer rulers imported Indian cultural practices, including Sanskrit, to create royal courts, with the kingdom of Funan serving as a key precursor to the powerful Khmer empire. Although few written records survived until the rise of the Khmer empire in the 9th century, archaeological evidence reveals a rich cultural heritage, with the discovery of artifacts like the Vedavyapi inscription providing valuable insights into the region’s history. The Khmer empire’s ascendancy marked a significant shift in the region’s politics and culture, as it became a dominant force in Southeast Asia, with its capital Angkor serving as a center of learning, art, and architecture.