5 The Emergence of Farming and Bantu Migrations

For thousands of years, African societies were characterized by small, nomadic groups of hunter-gatherers. However, with the introduction of plant and animal domestication techniques from the Fertile Crescent, this way of life began to change dramatically. The Neolithic Revolution, which spread to Africa around 7000 BCE, marked a significant turning point in the continent’s history.

The Emergence of Farming and Metallurgy

Agriculture emerged in three distinct regions of Africa: the Nile River valley in Egypt, the eastern Sahara in Sudan, and the great bend of the Niger River in West Africa.

- In Egypt, around 7000 BCE, agricultural technology and knowledge about domesticating wheat, barley, sheep, goats, and cattle were introduced from southwest Asia. This transformed the region and set Egypt on the path to greatness. Over the next few thousand years, these practices spread west across North Africa to Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco.

- In the grasslands south of the Sahara, agriculture emerged independently around 9000 BCE. The Nilo-Saharan people adopted grain-collecting and grinding techniques from their northern neighbors and applied them to sorghum and pearl millet. This was made possible by a millennia-long wet phase beginning around 11,000 BCE, which created a lush landscape. By 8000 BCE, the Nilo-Saharans had domesticated wild cattle and began producing pottery to store and cook grains. By 6000 BCE, they had begun to domesticate wild grains deliberately. Over time, they domesticated other plants like watermelons, cotton, and gourds.

- In the Niger River bend of West Africa, agriculture emerged independently around 3000 BCE. The Niger-Congo peoples domesticated yams and gradually developed agriculture, clearing land with stone tools to plant crops like yams, oil palm, peas, and groundnuts. They also domesticated a unique African variety of rice, grown in the Niger River wetlands.

Farming was enhanced by advances in metallurgy, which increased agricultural production and transformed the continent. Bronze technology, introduced to Egypt around 3000 BCE, spread west across North Africa and south up the Nile, allowing for more efficient farming practices. The Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten (c. 1353-1336 BCE) encouraged the use of bronze tools, which further accelerated agricultural development. Later, iron tools, initially used for ornamental purposes, became widespread after 1000 BCE, revolutionizing farming and leading to the spread of ironworking technology across West Africa. This, in turn, enabled the development of more complex societies and the expansion of trade networks. Around the confluence of the Benue and Niger Rivers in present-day Nigeria, the Nok people settled and initially used iron to create jewelry. However, they soon discovered the utility of iron for making farming tools and weapons, revolutionizing their agricultural practices. The durability and strength of iron tools enabled them to clear forests, aerate land, and construct complex irrigation systems.

As the benefits of ironworking technology became apparent, other groups adopted the new material, leading to its spread throughout West Africa over the next several centuries. The migrating Bantu people, in particular, found iron technology indispensable for their agricultural pursuits. With iron tools, they cleared surrounding trees, extended prehistoric irrigation systems, and created more efficient Iron Age farms. Through their migrations, the Bantu people disseminated ironworking technology throughout equatorial and subequatorial Africa, transforming the continent’s agricultural landscape. The adoption of iron tools enabled communities to increase food production, support growing populations, and lay the foundation for more complex societies. The spread of ironworking technology had a profound impact on African history, shaping the course of agricultural development, population growth, and cultural exchange.

Learn More

Watch this short video about the origins of ironworking in Africa (https://openstax.org/l/77Ironwork) to learn more. Pay close attention to the circumstances that led to the discovery of iron smelting in Africa and why iron metallurgy proved so revolutionary to the societies that adopted it.

The Bantu Migrations

The word “Bantu” is a modern term invented by linguists who have studied the languages of Africa. The word is made up of the common stem “ntu” and the plural prefix “ba” which put together literally means “people.” It describes a large and geographically widespread subfamily of African languages that make up part of the larger Niger-Congo language family. There are well over four hundred known Bantu languages spoken today across a large portion of the southern half of Africa.

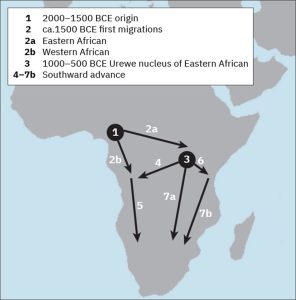

Between 3000 and 2000 BCE, the Bantu-speaking people embarked on a profound migration that would reshape the cultural and linguistic landscape of sub-Saharan Africa. This complex process, known as the Bantu expansion, involved multiple waves of migration and settlement. Initially, two distinct streams of Bantu migration emerged: an eastern stream and a western “rivers and coasts” stream. These pioneering groups gradually settled in the Great Lakes region of East Africa around 1500 BCE, subsequently spreading southward into modern Kenya, Tanzania, and southern East Africa. By the seventh century, Bantu communities had established themselves across a vast territory, stretching from Somalia to South Africa. This expansion had a profound impact on the development of later civilizations, including the Swahili speakers of the East African coast. The western stream of Bantu migration progressed at a slower pace, advancing south along the West African coast and into the Congo River system. A third phase of expansion occurred around the early centuries of the Common Era, with groups settling in modern Mozambique, Botswana, and eastern South Africa.

Source: OpenStax

The Bantu were among the earliest groups to benefit from the diffusion of farming, herding and animal keeping, and advanced metalworking technologies, and they dispersed across the continent changing its linguistic and cultural landscape along the way. Pioneers originating in West and Central Africa advanced sporadically as small groups of people moving from one point to another. During the earliest centuries of expansion, groups of Bantu arrived in regions that were only thinly populated by groups of nomadic hunter-gatherers. The land was unsettled, enabling the Bantu to select the best sites for their farms, and because there was no need to clear thick forest or adopt new techniques to suit a difficult environment, their expansion across the subcontinent proceeded relatively rapidly. New generations could simply move to new areas. Initially, then, Bantu farm settlements were typically confined to fertile river valleys and regions with favorable rainfall—which helps explain why they moved toward the southeast, a path that avoided the much drier southwest.

The situation changed, however, as the birth of each new generation put pressure on a given area’s limited resources. Growing needs necessitated further expansion, and as the Bantu advanced into the rainforest—their path helpfully cleared with new iron tools—they began to adjust their cultivation techniques to a variety of conditions. Although it may seem so, the tropical rainforest is not—and has never been—a uniform ecosystem: its topography and climate vary greatly from river valleys and swampy regions to dense forest canopies and plateaus, and across highlands and lowlands. Each of these environments requires different cultivation techniques, knowledge the Bantu acquired only after their gradual occupation of all parts of the rainforest and centuries of experimentation and adaptation. Their efforts were so effective that by the sixth century CE, Bantu farming communities had settled in virtually all parts of the tropical rainforest.

But the Bantu did not stop at the rainforest. Rather, they continued to drift southward and eventually emerged into the southern savanna, where they found an environment not unlike the grasslands they had encountered north of the rainforest. Like the rainforest, southern Africa was also lightly populated by foragers and hunter-gatherers, leaving vast swaths of land open for the Bantu farmers to inhabit. They expanded into this region seeking new land, a migratory process repeated by generations of their successors. Initially, the diffusion of the Bantu speakers south of the rainforest followed an easterly direction and hugged the southern and eastern edges of the rainforest. When they began to settle around Lake Victoria, the Bantu acquired cattle. From there, a general dispersal into eastern and southern Africa began.

Although the areas into which the Bantu migrated were only sparsely populated, interactions with the peoples who already lived there were unavoidable. It is not entirely clear what these meetings were like, but evidence suggests that interactions were complex and included elements of cultural absorption and assimilation as well as displacement, often at the same time. Early on, the Bantu moved in relatively small numbers, so there were no large-scale displacements of hunter-gatherer societies. It was some time before the Iron Age farmers came to dominate their Neolithic contemporaries.

At first, there was enough room for both societies to coexist in relative harmony. Oral tradition and linguistic evidence indicate that the Bantu intermingled with some of these populations, including rainforest-dwelling peoples such as the Twa and the Khoekhoe herders of South Africa. Had it not been for the rainforest dwellers, the Bantu may have had a far more difficult time adjusting to the environment. Indeed, Bantu oral tradition holds that it was rainforest dwellers like the Twa who taught them to adapt. It is also likely that the Bantu acquired their cattle—or at least their cattle-herding techniques—from the Khoisan, a cattle- and goat-herding people who preceded them in southern Africa. In fact, many of the words in the southern Bantu language that relate to cattle and cattle-herding practices are derived from Khoisan. This linguistic heritage is reinforced by the presence today of Khoisan “click” sounds in certain Bantu languages, particularly those of the south.

Core Impact Skill — Intercultural Competence

The Bantu migrations offer a way for us to understand the complexities of cultural contact over time. As Bantu-speaking peoples spread across sub-Saharan Africa, they didn’t simply displace others—they interacted with a wide range of communities, adapting to local conditions and absorbing new ideas. Rainforest peoples shared environmental knowledge; southern herders passed on cattle-raising practices and even vocabulary. These exchanges shaped the cultural and linguistic map of the continent.

Learning about these encounters helps us understand how people have long navigated difference—sometimes through conflict, but often through cooperation, borrowing, and adaptation. Intercultural competence grows from recognizing those patterns and thinking critically about how cultural identities are formed through contact.

-

What do the Bantu migrations reveal about how power and knowledge are negotiated between migrating and local communities?

-

How did long-term interaction—not just movement—shape the linguistic and cultural landscape of sub-Saharan Africa?

Studying the past reminds us that cultural exchange is not new—and understanding how people have negotiated difference over time helps us build the skills to do the same today.

Yet displacements did occur. The peoples who dwelled in the rainforest had all descended from a common population, but the arrival of the more technologically advanced Bantu farmers caused them to scatter into separate groups. On entering San territory, for example, the Bantu farmers displaced the previously dominant San and Khoekhoe peoples, the first inhabitants of South Africa. Forced from their home territories by the Iron Age farmers, the San and Khoekhoe embarked on their own widespread migrations. The Bantu were not dominant everywhere in southern Africa, however. In the drier, sandier areas of the western Kalahari Desert and Namibia, Khoisan speakers remained the dominant group until more recent times.

Link to Learning

As the Bantu migrated, did they arrive as conquerors, colonizers, or explorers? Listen to the BBC’s “The Story of Africa” (https://openstax.org/l/77StoryAfrica) and learn more.

Legacy of the Bantu Migrations

As the Bantu migrated, they encountered various groups, leading to a complex web of cultural exchange and transformation. They adopted local customs and practices, merged with existing populations, and sometimes displaced existing groups. The Bantu migrations were not a series of conquests, but rather a gradual process of expansion and cultural exchange. The interactions between the Bantu and existing populations were multifaceted, leading to the creation of new cultural practices and the transformation of existing ones. For example, the Bantu adopted the use of iron tools from the Nok people (c. 1000 BCE-300 CE) and incorporated their artistic traditions into their own culture.

The Bantu migrations (c. 3000-2000 BCE) had a profound impact on Africa’s economic and cultural practices, shaping the continent’s development for centuries to come. As the Bantu expanded across sub-Saharan Africa, they borrowed and adapted innovations in plant and animal husbandry, such as the domestication of sorghum, millet, and cattle, and metalworking techniques, like iron smelting and forging. This cultural exchange forged a common framework across the region, laying the groundwork for complex settled societies and later, large African states like medieval Great Zimbabwe (c. 1100-1450 CE), which became a major center of trade and commerce.

The Bantu migrations also facilitated the spread of iron working technology, which revolutionized farming practices and transformed the continent’s economic landscape. The introduction of iron tools, such as the plow and hoe, enabled farmers to cultivate more land and increase crop yields, leading to population growth and the development of more complex societies. Additionally, iron working technology enabled the production of weapons, like spears and swords, which played a significant role in the formation of African states and empires.

The Bantu migrations also had a significant impact on the development of African languages and cultures. As the Bantu expanded, they carried their languages, customs, and traditions with them, which eventually replaced or blended with existing languages and cultures. This process of cultural exchange and assimilation resulted in the development of new languages, such as Swahili, and cultural practices, like the use of masks and initiation rites.

Furthermore, the Bantu migrations played a crucial role in the development of African trade networks, which connected the continent to global trade routes. The Bantu established trade relationships with other African societies, exchanging goods like iron, copper, and ivory for salt, cloth, and other valuable commodities. These trade networks facilitated the spread of ideas, technologies, and cultural practices, shaping the course of African history.