6 Ancient Egypt

Along the life-giving waters of the Nile River, one of the most fascinating and influential civilizations of the ancient world emerged. Ancient Egypt, with its majestic pyramids, powerful pharaohs, and mysterious hieroglyphs, has captivated human imagination for millennia. Ancient Egypt’s transformative journey, spanning from its unification in 3100 BCE to the conquest by Alexander the Great in 332 BCE, encompasses a rich tapestry of political, social, and cultural advancements that defined this iconic civilization’s ascendance and decline

The Emergence of Ancient Egypt

Around 10,000 BCE, North Africa, including Egypt, was a lush and wet region, teeming with life. However, by 6000 BCE, the environment began to change, and the once-green landscape transformed into the arid Sahara Desert we know today. As the climate became more challenging, humans retreated to oases and rivers, including the Nile River valley. This narrow strip of fertile land, made possible by the Nile’s regular flooding, became a haven for early settlers.

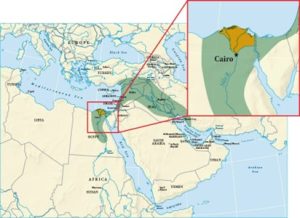

The Nile, the longest river in Africa and second-longest in the world, originates in central Africa and flows north through Egypt before emptying into the Mediterranean Sea. Around 7000-6000 BCE, agricultural technology and knowledge of domesticating plants and animals were introduced to the Nile River valley, likely through contact with the Levant. This marked the emergence of Egyptian culture, with two distinct Neolithic cultures arising in the Nile delta and upriver.

Over time, these cultures developed into two separate kingdoms: Lower Egypt (the delta region) and Upper Egypt (the area upriver). In approximately 3150 BCE, Upper and Lower Egypt were unified under a single powerful kingdom, possibly by King Narmer or Menes. This unification gave rise to the Early Dynasty Period (3150-2613 BCE), during which the earliest dynasties ruled a unified Egypt.

The powerful kings of these dynasties established a bureaucratic system, influenced by ancient Sumer’s economic model. Unlike Mesopotamia, ancient Egypt was a single state, protected by its geography. The Nile River valley was surrounded by vast deserts, making it an island in a hot, dry sea. During this period, many iconic cultural characteristics of ancient Egypt emerged, including the institution of the pharaoh, unique religious practices, and the Egyptian writing system.

The Pharaoh and Ancient Egyptian Society

When Egypt was first united around 3150 BCE, the pharaoh ruled over a vast kingdom of approximately two million people, far larger than any contemporary state. The term “pharaoh” translates to “big house,” likely referring to the vast palaces along the Nile Valley where the pharaoh resided and governed. These palaces featured extensive storage facilities for taxes paid in goods, as well as workshops for artisans producing goods for the palace. Like in Mesopotamia, the majority of the population were peasant farmers who paid taxes to support the artisans, officials, and priests living in the cities.

The pharaoh held a unique position, serving not only as a political leader but also as the high priest and a revered god. As high priest, the pharaoh unified the lands by performing religious rituals to honor various gods worshipped along the Nile Valley. As a deity, the pharaoh was believed to be the human incarnation of Horus, the god of justice and truth. Egyptians believed that the pharaoh’s divine presence maintained justice, peace, and prosperity, as evidenced by the annual flooding of the Nile.

In this role, the pharaoh was responsible for upholding the balance and order of the universe, ensuring the continued fertility and prosperity of the land. The pharaoh’s dual role as political leader and divine figure solidified their position as the ultimate authority in ancient Egyptian society.

Ancient Egyptian Spirituality and the Nile

The people of Ancient Egypt had a complex and multifaceted spiritual system, where various deities were associated with natural phenomena and cosmic forces. For instance, Re was revered as the embodiment of the sun’s life-giving power, while Isis was celebrated as a symbol of fertility and the earth’s abundance. Osiris, closely tied to the Nile, was a central figure in Egyptian mythology.

The annual flooding of the Nile was a pivotal event, explained through the myth of Osiris, which told the story of his death and resurrection. This narrative was deeply connected to the cyclical patterns of nature, where the Nile’s flooding brought life-giving water to the land. The pharaoh, as the earthly manifestation of Horus, was seen as the child of Isis and Osiris, emphasizing their role in maintaining balance and order.

The Nile’s predictable flooding fostered a sense of harmony and organization in the Egyptian worldview. Unlike the unpredictable and often destructive floods in Mesopotamia, the Nile’s cycles inspired a feeling of cosmic balance and justice. This concept evolved into the idea of Ma’at, which encompassed order, truth, justice, and equilibrium. Egyptians believed it was their duty to live in harmony with this balance, striving for a righteous life that would earn them a blessed afterlife.

In this context, the Egyptian spiritual system was not merely a collection of gods and myths but a complex web of beliefs that sought to explain the world and humanity’s place within it. By embracing the cyclical patterns of nature, Egyptians cultivated a sense of hope and optimism, believing that their world was geared toward a sense of cosmic justice.

Egyptian Writing

The ancient Egyptians created a distinctive writing system, known as hieroglyphics, which translates to “sacred writings” in Greek. However, the Egyptians referred to it as “medu-netjer,” meaning “the god’s words.” The origins of hieroglyphic writing date back to before the Early Dynastic Period, around 3000 BCE, when the first written symbols emerged. Over time, these symbols evolved into a complex script that combined:

- Alphabetic signs, representing sounds

- Syllabic signs, indicating sound combinations

- Word signs, symbolizing entire words

- Pictures of objects, conveying meaning

Only highly trained scribes were proficient in this intricate system, where written symbols represented both sounds and ideas. To simplify the process, the Egyptians developed a more straightforward version of hieroglyphics, known as hieratic. This script was used for everyday purposes, such as record-keeping and commercial transactions, like issuing receipts.

Gender Roles in Ancient Egypt

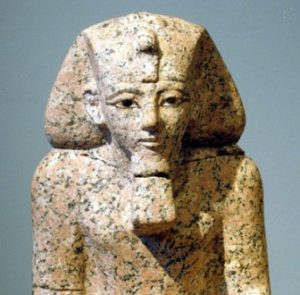

In Ancient Egypt, gender roles were well-defined and deeply ingrained in society. Men held dominant positions in government, religion, and commerce, while women’s roles were largely confined to the domestic sphere. However, unlike many ancient civilizations, Egyptian women enjoyed a relatively high status, with rights to own property, participate in trade, and even serve as priests in certain cults. A notable example is Hatshepsut, one of the few female pharaohs, who successfully ruled Egypt during the 15th century BCE and was known for her extensive building projects and trade expeditions. Despite these exceptions, men still held significant power and influence, and gender roles remained largely rigid. The ideal woman was expected to be a devoted wife, mother, and homemaker, while men were expected to be strong providers and protectors. These gender roles were perpetuated through art, literature, and religious teachings, shaping the daily lives of ancient Egyptians.

The Pyramids and the Afterlife

The pyramids of Ancient Egypt were elaborate tombs built for the pharaohs, where their bodies were preserved and protected after death. The Egyptians believed that a person consisted of multiple elements, including the Ka (spiritual double), Ba (spiritual essence), and Ahk (spirit that traveled to the afterlife). These beliefs made mummification and tomb construction crucial in Egyptian religion.

Before the pyramids, tombs were built using mud-brick and called mastabas. However, during the Early Dynastic Period, the architect Imhotep designed a stone tomb for Pharaoh Djoser, which evolved into the step pyramid. This innovative design led to the construction of larger pyramids, like the one built for Pharaoh Khufu, which took around 20 years to complete with a workforce of approximately 20,000 laborers.

As the pyramids grew in size and number, so did the power of priests and administrators managing them. This led to a decentralization of power, weakening the pharaoh’s control. By around 2200 BCE, priests and regional governors had amassed significant wealth and power, marking the beginning of the First Intermediate Period.

A Second Age of Egyptian Greatness

The First Intermediate Period ended around 2040 BCE, and the Middle Kingdom Period began. This era saw powerful rulers like Mentuhotep II and Amenemhat, who reestablished centralized control and introduced the cult of Amon-Re, a powerful deity who combined the characteristics of the sun-god Re and the sky god Amon. Amon-Re was revered as the king of the gods and the father of each pharaoh, solidifying the pharaoh’s divine authority. Unlike their predecessors, Middle Kingdom pharaohs abandoned the construction of massive pyramids in favor of building grand temples dedicated to Amon-Re and his consort, Mut, at Thebes. The remnants of these temples can be found at Karnak in southern Egypt. These temples featured impressive architecture, including vast halls with multiple columns, courtyards, and ceremonial gates, which served as the focal point for religious rituals and processions. On special occasions, the sacred images of Amon-Re and Mut were paraded through the streets, further emphasizing their importance in Egyptian society.

Link to Learning

New Kingdom pharaohs circulated a work of literature that foretold the rise of Amenemhat, who would bring an end to disorder and restore Egypt to prosperity. This ancient work was called the Prophecy of Neferty (https://openstax.org/l/77prophecy) and is presented as an English translation by University College London.

The pharaohs of this period focused on building massive temples instead of pyramids and expanded Egypt’s territorial control through military campaigns. Senusret III, a powerful warrior pharaoh, reached the height of Middle Kingdom Egypt’s power in the 1870s and 1860s BCE. He expanded Egypt’s control, led armies into Kush and the Levant, and increased trade. This led to a cultural flourishing, with refined art, architecture, and literature. After Senusret III’s death, Egypt experienced a decline. The pharaohs’ power weakened, and Semitic-speaking peoples from the Levant flowed into Egypt. By the late 1700s BCE, these groups had grown numerous, and their chieftains, called Hyksos, began to assert control. This marked the beginning of the Second Intermediate Period, a time of reduced centralized control.

Egypt was split into three regions: the north ruled by Hyksos, the south by Kush, and the center by Egyptian nobles. Despite fragmentation, the regions maintained peaceful relationships until the 1550s BCE, when Theban Egyptian rulers went on the offensive against the Hyksos. After defeating the Hyksos, the Egyptians turned their attention to Kush, extending their control and ushering in the New Kingdom Period, the highest point of Egyptian power and cultural influence.

The New Kingdom period (c. 1550-1069 BCE) marked the pinnacle of Egyptian power and influence. Pharaohs like Ahmose (r. 1570-1546 BCE), who recovered Lower Egypt, Nubia, and Palestine, and Amenhotep I (r. 1525-1504 BCE), who expanded Egypt’s reach, were renowned for their military prowess and architectural achievements. The elevation of Amun, the Thebans’ patron god, coincided with the rise of the New Kingdom pharaohs. Amenhotep I and his successors built temples in Amun’s honor, particularly the great Temple of Amun at Karnak. Thebes became the state’s religious capital and royal burial place, known as the Valley of the Kings.

Queen Hatshepsut (r. 1479-1458 BCE) assumed the throne after her husband’s death and proclaimed herself co-regent with her stepson, Thutmose III. She claimed divinity, citing a poem that described her heavenly origins and divine right to rule. Her reign was marked by prosperity, military campaigns, and extensive building projects, including her mortuary temple. Thutmose III (r. 1458-1425 BCE) took control after Hatshepsut’s death and eliminated her from historical records. He continued successful military campaigns and expanded Egypt’s influence. His successors, including Amenhotep III (r. 1390-1352 BCE) and Akhenaten (r. 1353-1336 BCE), emphasized the worship of Aton, the sun god, and built extensive monuments. The Ramesside kings, beginning with Ramesses I (r. 1292-1290 BCE), worked to restore Egypt’s greatness. Ramesses II (r. 1279-1213 BCE), the last great pharaoh of the New Kingdom, fought wars with the Hittites and Libyans, and launched impressive building campaigns. His reign marked the end of Egypt’s golden age.

As the New Kingdom era drew to a close, Egypt’s control over trade routes in Canaan and Syria weakened. Instability and banditry increased, making travel hazardous. An Egyptian envoy’s journey to Phoenicia around 1100 BCE illustrates the challenges. He was robbed by his own crew, denied the cedar he sought, and attacked by migrants. Egyptian officials could do little to help. These problems were symptoms of the Late Bronze Age Collapse, a broader decline affecting the eastern Mediterranean. Large numbers of migrants, known as the Sea Peoples, swept across the region, bringing chaos and destruction. An Egyptian inscription from 1208 BCE described them as “coming from the sea.” Many likely originated from the Aegean area. This marked the end of Egypt’s dominance in the region, as the country struggled to cope with the consequences of this civilizational decline. By 1070 BCE, the challenges had been mounting for years, and the New Kingdom came to an end.

The Significance of Ancient Egypt for World History

The significance of ancient Egypt in world history is profound and far-reaching. As one of the earliest civilizations, Egypt’s contributions to human progress have had a lasting impact. The development of hieroglyphic writing, monumental architecture, and sophisticated medical practices are just a few examples of Egypt’s enduring legacy. Moreover, Egypt’s strategic location facilitated cultural exchange and trade between Africa, Asia, and Europe, making it a pivotal crossroads of ancient civilizations.

The legacy of Egypt continues to influence contemporary society. The majestic pyramids, temples, and tombs that line the Nile River valley stand as testaments to the ingenuity and creativity of the Egyptian people. The stories of pharaohs, gods, and mythological legends have captivated human imagination for millennia, inspiring countless works of art, literature, and film. As we reflect on the history of Egypt, we are reminded of the power of human achievement and the lasting impact of a single civilization on the trajectory of world history.