9 The Swahili Coast and the Indian Ocean Trade

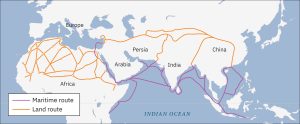

Africa’s strategic position at the crossroads of the ancient world made it a vital hub in the global networks of the silk and ocean trades. From the dawn of civilization, African kingdoms and empires played a significant role in the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures between the Mediterranean, Asia, and the Indian Ocean. As early as 3000 BCE, Egyptian pharaohs were trading with Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley, while later, the kingdoms of Axum and Kush dominated the Red Sea trade in ivory, gold, and spices. Meanwhile, the Swahili city-states of East Africa thrived on the Indian Ocean trade, connecting the continent to the vast networks of the Silk Road.

Source: OpenStax

East Africa and the Indian Ocean Trade

East Africa played a crucial role in the Indian Ocean trade network, connecting the region with the Middle East, China, and Southeast Asia. Initially, trade centered on the Red Sea, with luxury goods like ivory, furs, and spices being exchanged with the Roman Empire. Following the Roman Empire’s collapse, Arabian traders took over this trade, and as Bantu-speaking Africans moved into the region, a sophisticated culture emerged on the Swahili coast.

Source: OpenStax

In the third century CE, traders from Saba, in present-day Yemen, crossed the Red Sea to the coast of Eritrea, establishing the port city of Adulis. The Kingdom of Aksum, with its capital eight days’ journey south, owed its power to this Red Sea trade, particularly during the reign of King Ezana (c. 320-360 CE). Goods traded included gold, silver, iron tools, cotton cloth, tortoise shells, ivory, and spices like frankincense and myrrh. King Ezana expanded the kingdom to its farthest extent, conquering peoples south of Egypt and north of Ethiopia. In 350 CE, he was converted to Christianity by the Syrian missionary Frumentius.

In the sixth and seventh centuries, the Kingdom of Aksum expanded its control under King Kaleb (c. 520-540 CE), but eventually overextended itself. The Sasanids from Persia and the Arab Muslim population, particularly the Umayyads, conquered the region. In 528 CE, the Aksumites expanded their control as far as Yemen, but were pushed out of the peninsula by the king of Yemen, Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan, with the help of the Sasanids. The Aksumite Kingdom collapsed, and internal problems, including environmental degradation and soil erosion caused by intensive agriculture and deforestation, further weakened the kingdom. Additionally, the kingdom’s excessive reliance on wood fuel and overgrazing led to widespread environmental damage, exacerbating the decline of the kingdom. As Islam expanded, the Persian Gulf became increasingly important for oceangoing vessels, bypassing the Aksumite port of Adulis.

Despite the decline of the Aksumite Kingdom, its legacy lived on as the foundation of the Ethiopian Empire, which would eventually become the modern country of Ethiopia. The region remained a thriving cultural hub, combining traditional pre-Islamic Jewish traditions, indigenous spiritual practices that emphasized ancestor reverence and nature-based beliefs, and Christianity. The region’s cultural significance continued well into the modern era, with legends like the Christian kingdom of Prester John, a mythical Christian kingdom believed to exist in East Africa during the Middle Ages, and the Ark of the Covenant (which would later capture the imagination of adventurers like Indiana Jones in “Raiders of the Lost Ark”), a gold-covered wooden chest believed to contain the Ten Commandments, contributing to its rich heritage. These legends highlight the region’s importance in medieval European imagination and its enduring cultural significance.

The Swahili Coast and Indian Ocean Trade

As the Kingdom of Aksum declined, Bantu peoples migrated from northwest Africa to the east and southeast, driven by internal forces. The Bantu brought their language, their cultural traditions, and especially the technology of ironmongering. Many began settling in coastal communities in East Africa, where they displaced or mixed with the Khoisan and other indigenous African peoples, particularly on the coasts of modern Tanzania and Kenya. They also traveled south, establishing many fishing and trading villages. These exported ivory, hides, quartz, and gems in return for cotton, glass, jewelry, and other items the Bantu people were unable to make themselves. Port towns such as Shang and Manda began growing into major port centers. Soon Arab merchants began living among the Bantu peoples to participate in the newly developing trade.

The expanding trade with the Muslim world transformed the Swahili coast into a thriving region of city-states that emerged during the Middle Ages and specialized in luxury goods exchange. Yemeni traders, including the Kharijites, dissident Muslims from Arabia, established a powerful presence on the East African coast in the eighth century, forging complex networks of exchange with local merchant families, villages, and towns. As they built these relationships, they intermarried and blended Arab, Persian, and Bantu cultures and languages, creating the Swahili civilization.

The merchant ruling class held elite status, while the second class consisted of townspeople, artisans, clerks, and other non-elite workers. Non-Muslims, such as servants and manual laborers, held even lower social status. The lowest class was enslaved people, purchased from the mainland to work on farms. Slavery was prevalent in East Africa, as it was in the Atlantic world during European colonization. Enslaved people were traded in the Indian Ocean network, with merchants buying Bantu people from African intermediaries and shipping them to southern Iraq. There, they worked to drain swamps and grow crops. In 868 CE, the Zanj enslaved people rebelled, but were crushed in 883 CE. This uprising ended large-scale slave trade between the Swahili coast and Persian Gulf, although slavery continued in the Indian Ocean network.

After 1050 CE, a new wave of Muslim immigrants arrived from the Persian Gulf region, claiming heritage from the city of Shiraz in Iran. They settled along the East African coast, particularly in cities like Mombasa, Malindi, Lamu, and Sofala. As they integrated with the local Bantu-speaking populations, they retained their Islamic cultural heritage and contributed to the development of the Kiswahili language, which blended Bantu roots with Arabic influences. These Shirazi Muslims played a significant role in dominating trade along the coast and on nearby islands like Pemba, Mafia, and Zanzibar, while also emphasizing their Persian heritage to establish their legitimacy in the region.

About forty new Muslim towns formed, many of them city-states independently ruled by their own sultans. A council of wealthy patricians served as advisors or sometimes simply ran the town without a sultan. In either case they formed an elite, hereditary merchant class, speaking Arabic or Kiswahili and trading with Africans in the interior for such items as ivory, furs, and gold. Gold came from Sofala, the southernmost settled point at that time, and was shipped to the northern part of the Swahili coast, where it was traded to the city-states and from there to the Indian Ocean trade network. The merchants of the city-state of Kilwa sought to bypass intermediaries and purchase gold directly. They therefore established the trading colony of Sofala in the region of the same name. Mostly due to its domination of the gold trade, Kilwa became the most important of the Swahili towns, although Zanzibar proved nearly as powerful. For periods in the fourteenth century CE, in fact, Kilwa ruled over many other towns.

The development of the Swahili city-states also had the effect of connecting the interior of central southern Africa with the wider trade of the Indian Ocean basin. Merchants from city-states such as Sofala, for example, traveled up the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers to the great fairs that took place on the Zimbabwean plateau, a region dominated by the Bantu peoples of Great Zimbabwe. There they exchanged shells, ceramics, and coins from the East African coast for such high-value luxury goods as gold and ivory.

The Legacy of East African Trade

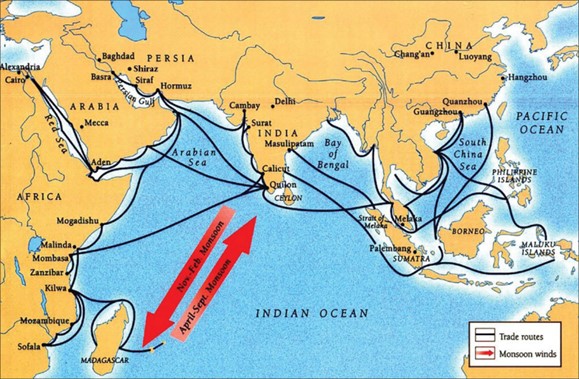

By the twelfth century CE, East Africa had emerged as a pivotal hub in the Indian Ocean trade network, rivaling other major centers like the Middle East and South Asia. The region’s strategic location allowed it to capitalize on the monsoon winds, which enabled ships to sail towards India during the summer months and towards Africa during the winter months. As trade-based societies flourished along the extensive coastline of the Indian Ocean, a shared culture began to take shape. Merchants and traders from diverse backgrounds interacted, influencing each other’s customs, languages, and beliefs. This cultural exchange had a profound impact on the development of East African societies, shaping their art, architecture, and literature.

Core Impact Skill — Intercultural Competence

The history of East Africa’s coastal cities helps us understand intercultural competence by revealing how diverse cultural influences can blend into something new without erasing their origins. By the twelfth century, East African port cities had become dynamic centers where African, Arab, Persian, Indian, and later even Chinese influences met—not only to trade goods, but to live, worship, intermarry, and create. Out of these interactions emerged Swahili culture, a fusion expressed in language, religion, architecture, and everyday life.

We learn about intercultural competence by studying how East African societies developed shared practices while maintaining distinct cultural roots. Rather than simply adopting foreign customs, they reshaped them into something locally meaningful. Swahili civilization was not a product of one culture influencing another—it was built through generations of negotiation, adaptation, and shared experience.

-

How does the development of Swahili identity challenge ideas about cultural “purity” or one-way influence?

-

What does the long-term coexistence of multiple languages, religions, and customs in East Africa teach us about the possibilities and limits of cultural blending?

By examining how East African societies forged a hybrid identity through everyday interaction, we gain insight into how cultural diversity has long been a source of creativity, not conflict.

The Indian Ocean trade network was fueled by the demand for luxury goods and natural resources. East Africa’s rich wildlife and natural resources, including ivory, animals, skins, rhinoceros’ horns, and gold, were highly prized by merchants and traders. In exchange, East African societies received coveted luxuries like silks, glassware, and tools, which became symbols of wealth and status.

The legacy of East African trade can still be seen today, with many of the region’s cities and ports continuing to thrive as centers of commerce and cultural exchange. The blending of cultures, languages, and beliefs that occurred during this period has left an indelible mark on the region’s identity, shaping the course of East African history and its place in the global community.