10 Belief and Power: The Growth of Christianity and Islam in Africa Before 1500

From the earliest Christian kingdoms to the eve of the Age of Exploration, Africa underwent profound transformations. This period saw the rise and fall of powerful empires, including Axum, Ghana, Mali, Great Zimbabwe, and the Egyptian Mamluks, which shaped the continent’s political landscape. The spread of Islam from the 8th century CE had a profound impact, influencing trade, culture, and religion across North Africa and beyond. Complex trade networks emerged, connecting West Africa to the Mediterranean, East Africa to the Indian Ocean, and North Africa to Europe. Meanwhile, the Bantu migrations reshaped the demographics of central and southern Africa, while the Swahili city-states flourished along the Indian Ocean coast.

The Expansion of Christianity in Africa

The Roman Empire’s expansion created a fertile ground for Christianity’s growth, illustrating the intricate relationship between historical events in the region. As Christianity’s influence increased, it sparked concern among Roman officials, who viewed it as a potential disruptor of social order. This led to a wave of persecutions, initiated by Emperor Decius in 250 CE and escalated by Emperor Diocletian in 303 CE. Many Christians fled to the Western Desert of Egypt, where they sought refuge in solitude as hermits or established communal monasteries.

In the 3rd century CE, Christianity spread westward from Egypt along the North African coast to the Maghreb region, encompassing modern-day Morocco, Libya, and parts of the Sahara. Carthage, a major city in this region, became a hub for Christianity, but its community faced Roman persecution. Perpetua and her pregnant servant Felicitas, who were executed in 203 CE, exemplify the victims of Roman persecution. They were put to death in the arena at Carthage, along with other Christians.

By the 4th century CE, three distinct forms of monasticism emerged in northeast Africa. In northern Egypt, solitary hermits like Anthony of the Desert (251-356 CE) continued to live in isolation. In contrast, southern and northwestern Egypt saw the rise of communal monasticism, where devout men and women lived together, sharing daily tasks and spiritual practices. Women also joined monastic communities, with some opting for solitary asceticism.

Frumentius’ missionary efforts in Ethiopia marked a significant milestone in African Christianity. After being shipwrecked on the Eritrean coast, Frumentius became a tutor to King Ezana (r. 330-356 CE) and converted him to Christianity. Following his baptism, King Ezana sent Frumentius to Alexandria to request a bishop for Ethiopia. The bishop of Alexandria, Athanasius, appointed Frumentius as bishop, and he founded Ethiopia’s first Christian monastery.

Meanwhile, in North Africa, the Christian community faced new challenges. The consequences of Roman persecution and the complexities of maintaining their faith in a hostile environment led some Christians to renounce their faith publicly while continuing to practice it in secret. This practice, known as “traditio,” involved handing over scriptures to Roman authorities. However, others saw this as a betrayal of their faith. After the Edict of Milan (313 CE) granted religious toleration, a rift emerged in the North African Christian community. The Donatist controversy, led by Bishop Donatus, refused to recognize leaders who had renounced their faith during persecution. They deemed sacraments performed by these leaders invalid, including baptisms, weddings, and clergy consecrations. Emperor Constantine intervened, exiling Donatus to Gaul (modern France) in 347 CE, but the controversy persisted.

Augustine of Hippo, a renowned Christian thinker, played a crucial role in resolving the Donatist controversy. He became bishop of Hippo in 395 CE and opposed the Donatist view, ultimately leading to their expulsion from the church. In addition to his triumph over the Donatist schism, Augustine made a lasting impact on the early Christian church through his extensive writings on doctrine. His most influential work, The City of God, was written in response to the Visigoths’ sack of Rome in 410 CE. In this treatise, Augustine argued that human-made kingdoms, including Rome, are impermanent and vulnerable to collapse. Conversely, the Kingdom of God, comprising faithful Christians, would persist indefinitely. By articulating this vision, Augustine reassured Christians shaken by Rome’s near destruction that the Kingdom of God, built over centuries, would endure, providing a sense of continuity and hope amidst temporal turmoil.

Link to Learning

Learn more about Augustine’s concept (https://openstax.org/l/77Augustine) of the two cities—the earthly and the heavenly—by reading excerpts from his early work of Christian philosophy, The City of God.

Augustine played a significant role in shaping Christianity into a more unified faith across the Roman Empire. However, as Christianity spread, religious persecution of pagans by Christians increased throughout the empire. A notable example of this violence occurred in Alexandria in 415 CE, when a Christian mob brutally murdered Hypatia, a pagan philosopher. This event marked a turning point in the assertion of Christian dominance and the suppression of pagan beliefs.

As the Christian Roman state expanded, it tolerated and encouraged violence against pagans, leading to temple destruction and persecution. Meanwhile, the church leadership sought a uniform doctrine, culminating in the 451 CE Council of Chalcedon. This council sparked intense debate about Jesus Christ’s nature, with the Coptic Church in Egypt rejecting the Chalcedonian definition and affirming Monophysitism, alongside other churches like the Ethiopian and Armenian churches. This theological divergence contributed to distinct traditions within the Christian world.

Coptic Christianity developed a distinct identity, separate from broader Roman Empire Christianity. The Christian Kingdom of Aksum, which followed Coptic Christianity, flourished until its 10th-century overthrow by Queen Gudit. The subsequent Zagwe Kingdom continued the Coptic tradition, with King Lalibela commissioning remarkable rock-hewn churches and establishing a major pilgrimage site. By the 13th century, the Coptic Church’s unique identity had shaped the culture and politics of affiliated African kingdoms, influencing their relationships with other Christian communities.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

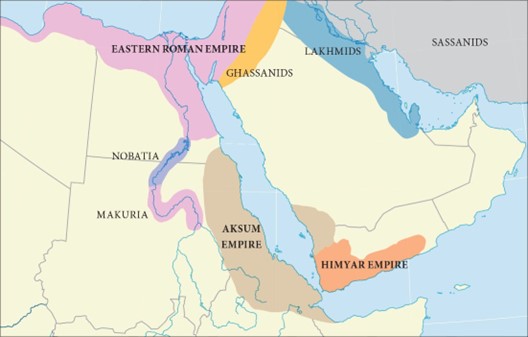

The Kingdom of Aksum

The Kingdom of Aksum flourished in sub-Saharan Africa from the first century BCE to the eighth century CE, emerging as a significant counterpoint to the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires. Strategically located in modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea, Aksum leveraged its proximity to the Red Sea to expand its territories across the sea into southern Arabia, establishing a brief but significant presence on the Arabian Peninsula. At its height from the third to the sixth century CE, Aksum was a powerful economic force, trading luxury goods like ivory, myrrh, and frankincense with Egypt, Arabia, and the eastern Mediterranean, with its currency, the Aksumite gold coin, widely accepted. The kingdom’s prosperity was further bolstered by its rich agricultural land, which supported a large population and enabled the Aksumites to build impressive architectural monuments, such as the Stelae of Aksum, showcasing a unique blend of African, Arabian, and Mediterranean influences in their culture and traditions.

A Map of the Aksum Kingdom

(attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

Founded by King Zoskales in the 1st century BCE, Aksum rose to prominence under the rule of King Ezana in the 4th century CE, who expanded the kingdom’s borders through military conquests and established trade relationships with the Roman Empire. Ezana’s reign is also notable for the introduction of Christianity to Aksum, which became a central aspect of the kingdom’s culture and identity. The kingdom’s strategic location on the Red Sea made it a crucial hub for trade between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean, with merchants like Cosmas Indicopleustes visiting Aksum in the 6th century CE.

In the ancient Kingdom of Aksum, daily life was shaped by a distinctive cultural fusion of African, Arabian, and Mediterranean influences. The population resided in stone and wood dwellings, with the affluent inhabiting grandiose villas featuring intricate carvings and sculptures that reflected the kingdom’s architectural prowess. As a major hub for trade, Aksum’s streets bustled with merchants and travelers from diverse corners of the ancient world, exchanging goods and ideas. Citizens engaged in various occupations, including agriculture, herding, and craftsmanship, with skilled artisans renowned for their exceptional textiles, pottery, and metalwork. The official language was Ge’ez, although Greek and Sabean were also widely spoken, facilitating communication among the kingdom’s diverse population. Aksumites practiced a syncretic mix of Christianity, Judaism, and traditional African religions, with rulers often depicted in art and literature as wise and powerful leaders. Despite social stratification, Aksum’s culture placed a high value on education, art, and architecture, fostering a sense of civic pride among its citizens.

During King Kaleb’s sixth-century reign, Christianity continued to thrive in Aksum, with churches becoming a ubiquitous feature in Aksumite cities, many of which were constructed during this period with inscriptions crediting Kaleb for his contributions. Aksumite churches typically followed Byzantine designs, with oblong shapes and rounded apses, although some featured unique circular plans possibly inspired by local house types. At its zenith, Aksumite society extended its cultural and political influence into southern Arabia, where Kaleb launched a military campaign against the Himyarite king Dhu Nuwas to support local Christian communities. This campaign was motivated by both Christian ideology and a claimed lineage to King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, leading to an alliance with the Byzantine emperor Justin to subdue Dhu Nuwas and establish Aksumite control over southern Arabia until the Sasanian conquest in 572.

Life in Aksum was marked by a unique fusion of African, Christian, and Mediterranean influences, with men and women playing distinct roles in the kingdom’s prosperity. Men dominated the kingdom’s vast trade networks, exchanging ivory, spices, and precious metals like gold and copper, while women were central to the production of textiles, pottery, and other crafts. Farmers, often men, cultivated crops such as barley, wheat, and teff (a small, gluten-free grain) using terracing and water management techniques, while women oversaw the processing and preparation of these crops for the community. Aksum’s strategic position enabled the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures with the Mediterranean and beyond, establishing the kingdom as a center of learning, art, and architecture, with men and women both contributing to its enduring legacy.

Aksum’s golden age began to decline in the 7th century CE, primarily due to internal factors such as political instability, economic strain, and environmental degradation. The kingdom’s extensive trade network, once a cornerstone of its prosperity, became increasingly difficult to maintain due to mismanagement and corruption. Meanwhile, the Aksumite monarchy faced challenges from regional nobles and rival claimants, further weakening the central authority. As the kingdom’s power waned, it became vulnerable to external influences. The last known king of Aksum, Dil Na’od (reigned c. 917-940 CE), attempted to revive the kingdom’s fortunes, but his efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, and the Aksumite Kingdom was eventually overtaken by the Zagwe dynasty, marking the end of an era.

Aksum’s legacy, however, endured in Ethiopia, influencing the region’s cultural, religious, and architectural development. The kingdom’s rich cultural heritage, including its unique blend of African, Arabian, and Mediterranean traditions, continued to shape the identity of the Ethiopian people. The Aksumite architectural style, characterized by stone and wood structures, was adopted and adapted by later Ethiopian kingdoms, such as the Zagwe and Solomonic dynasties. Additionally, Aksum’s Christian traditions and liturgical practices were preserved and developed by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, which remains an integral part of Ethiopian culture to this day. Overall, Aksum’s enduring legacy is a testament to the kingdom’s significant impact on the history and culture of Ethiopia.

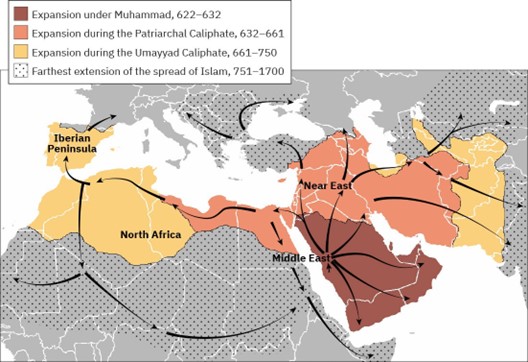

The Expansion of Islam in Africa

The expansion of Islam in Africa was a complex process that involved cultural diffusion, trade, and missionary work. By the start of the seventh century, Christianity seemed firmly entrenched across Egypt and the Maghreb, a region in North Africa encompassing modern-day Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Mauritania, but Islam quickly spread across the region. The spread of Islam in Africa was shaped by various factors, including trade, cultural exchange, and missionary work. Muslim traders, scholars, and missionaries played a significant role in diffusing Islamic ideas throughout West, East, and sub-Saharan Africa. The trans-Saharan trade routes helped spread Islam to West African trading towns like Gao and Koumbi Saleh.

In the eighth century CE, Muslim traders from Arabia and Egypt established themselves in towns and trading centers along the Swahili coast, a region of eastern Africa bordering the Indian Ocean. Here, they found thriving Bantu communities, whose settlement and prosperity were closely tied to their role in regional and international trade. As Arab and Bantu populations interacted, they formed a distinctive cultural blend, characterized by a unique language and urban, trade-based way of life. This blending of cultures enriched the region’s diversity and laid the groundwork for a vibrant, cosmopolitan society.

By the tenth century CE, the Swahili coast was acknowledged as an important commercial center. Writing in 915 CE, the Arab traveler al-Masudi described the area’s vigorous trade, which included exports of everything from ambergris and ivory to gold and leopard skins and such imports as stone bowls, Islamic pottery, and glass vessels. Thus, a distinct Swahili civilization had emerged, speaking a distinct Arabic-Bantu dialect, oriented toward the sea rather than the African interior, dominated by independent city-states that specialized in trade, and Islamic in faith. This Swahili language and culture had a powerful influence in the towns of the east African coast.

During the 11th century, Islam’s influence expanded across North Africa, but its impact in West Africa remained limited. The Amazigh people, also known as Berbers, combined Islamic practices with their indigenous traditions, resulting in a unique blend of faiths. However, Abdullah ibn Yasin, a prominent Islamic scholar, disagreed with this fusion of beliefs. He advocated for a more traditional understanding of Islam, seeking to refine the faith by eliminating practices that deviated from its established teachings.

Ibn Yasin established the Almoravid dynasty in Morocco, aiming to propagate his vision of orthodox Islam. The Almoravids experienced rapid growth, conquering a vast territory that stretched from Morocco to the Ghana Empire by the 1070s. By the mid-12th century, the Almoravid dynasty’s military expansion slowed, and they focused on consolidating power in Morocco. Meanwhile, Ibn Tumart, another influential Islamic scholar, emerged as a leader among the Amazigh. He led a successful reformist war, establishing the Almohad Empire. The Almohads built upon the Almoravids’ legacy, further spreading orthodox Islam throughout the region.

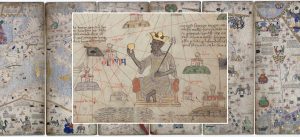

However, by the 13th century, the Almohad Empire also began to decline, weakened by internal conflicts and external pressures. This power vacuum created an opportunity for the kingdom of Mali to rise to prominence. By the thirteenth century, Mali had become the dominant political and economic force in the region. Unlike the rulers of Ghana, the Malian elite—including the mansa or king—converted to Islam. Mansa Musa, perhaps the most famous ruler of Mali, drew the attention of observers from Arabia to Spain when he went on pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324–1325.

Source: OpenStax

Renowned for the wealth of his kingdom, Mansa Musa distributed so much gold during a stopover in Cairo that the Egyptian economy suffered high inflation for more than a decade according to some reports. On his return to Mali, Mansa Musa brought with him Muslim scholars, architects, and books, all of which helped deepen the Islamic character of Mali. At Timbuktu, for example, the Djinguereber Mosque was built, and schools and universities specializing in the study of the Quran were established, cementing that city’s growing international status as a place of Islamic scholarship and learning.

By the end of the fourteenth century, West African rulers from Mali to Hausaland (present-day Nigeria) had adopted Islam, creating a broad Muslim presence across sub-Saharan Africa. Islam’s influence extended into East Africa, where it intersected with the existing Christian communities in the kingdoms of Nubia and the Ethiopian Kingdom of Aksum. Over time, Islam’s presence grew, and by the 1200s CE, many Christian kingdoms had adopted Islam. However, the Kingdom of Abyssinia, which emerged from the legacy of Aksum and Zagwe, continued to be a significant hub of Christian tradition and practice. In the African Horn, the Muslim sultanates of Ajuran and later Adal developed, contributing to the region’s diverse religious landscape.

As Islam’s influence expanded across Africa, its mystical dimension, Sufism, also began to take root in the northern regions. By the 12th century, Sufi orders had established themselves in the Maghreb region, attracting followers with their emphasis on spiritual growth and love. Sufi lodges and shrines became centers of learning and devotion, blending Islamic mysticism with local customs and traditions. This unique blend of Sufism and Berber culture helped shape the region’s Islamic identity.

The growth of Sufism in Northern Africa was further facilitated by influential Sufi scholars and saints, such as Abu Madyan (1126-1198), Ibn Arabi (1165-1240), and Abdul Qadir Gilani (1078-1166). These leaders developed distinctive North African Sufi traditions, which emphasized spiritual purification and the pursuit of divine love. As a result, Sufism became an integral part of the region’s religious and cultural life, influencing art, literature, and music. By the 15th century, Sufism had become a dominant force in Northern African Islam, with Sufi lodges and shrines remaining vital centers of spiritual practice and learning. Sufism’s presence was more limited in sub-Saharan Africa, it still had a profound impact on local Islamic practices and traditions, particularly in West Africa, where it shaped the spiritual landscape.

Religious Transformations and Their Lasting Effects on Africa

The legacy of religious conversion in Africa is complex and multifaceted, with far-reaching consequences for the continent’s cultural, social, and political landscape. The introduction of Christianity and Islam brought new ideas, technologies, and networks that facilitated Africa’s integration into global systems of trade and learning. However, this process also entailed the displacement of indigenous practices and epistemologies, leading to cultural erasure and the loss of traditional knowledge. Many African societies adapted these faiths to their own contexts, creating vibrant and distinctive religious traditions that continue to thrive today.

Core Impact Skill — Intercultural Competence

The history of religious conversion in Africa helps us understand intercultural competence by showing how people respond to powerful cultural forces without simply accepting or rejecting them. The spread of Christianity and Islam brought major shifts in worldview, practice, and identity—but it also sparked creative adaptation. Across the continent, African communities blended new religious systems with existing beliefs, creating traditions that were neither fully foreign nor entirely indigenous.

We learn about intercultural competence by studying how African societies negotiated religious change—sometimes through resistance, sometimes through synthesis, but always on their own terms. The resulting diversity is not a sign of confusion or loss, but of cultural agency: the ability to shape identity through meaningful engagement with difference.

-

How does the blending of Christianity, Islam, and African traditional religions challenge binary ideas of conversion or rejection?

-

What can Africa’s religious history teach us about how communities adapt global influences while preserving local meaning?

By examining these layered histories, we gain insight into how intercultural encounters can lead to the creation of new ways of believing, knowing, and being.

In contemporary Africa, the encounter between Christianity, Islam, and African traditional religions has yielded a rich and dynamic religious diversity. From the Afro-Christian movements of West Africa to the Islamic Sufi orders of North Africa, people blend, adapt, and reimagine their religious traditions in countless ways. This creativity and agency in the face of historical change underscore the significance of religious encounters in shaping Africa’s cultural identity and informing its responses to globalization.