12 Sub-Saharan Africa in the First Millenium

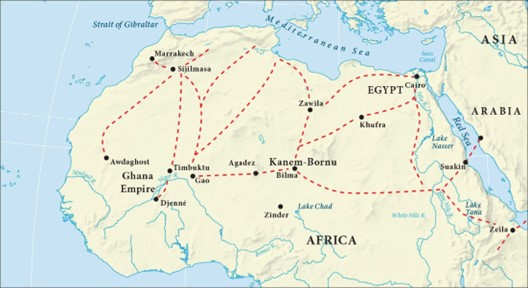

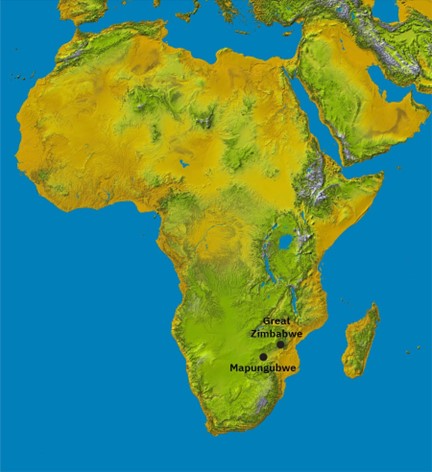

For nearly seven hundred years, powerful empires and kingdoms shaped the economies and politics of West Africa and southern Africa, from the rise of Ghana to the influence of Mali and Great Zimbabwe. The wealth of these states and thus their power came from their control of trade in commodities such as gold, ivory, salt, silk, horses, and enslaved people. In West Africa, the kingdoms of Ghana and Mali moved these goods along a sprawling network of trade that stretched across North Africa, eastward into Ethiopia, and southward as far as the grassland savanna, connecting West Africa to the Mediterranean world, Europe, the Near East, southwest Asia, and beyond. In southern Africa, Mapungubwe and then Great Zimbabwe consolidated their control over local and regional trade and connected their economies with the coastal civilization of the Swahili peoples through a network of waterways that included the Limpopo and Zambezi Rivers. In so doing, they linked the southern African interior with the distant and overlapping nodes of oceanic commerce that connected East Africa with Asia and Arabia.

The Ghana Kingdom

The Ghana Kingdom, which flourished from the 6th to the 13th centuries, was a powerful and influential kingdom that dominated the region between western Mali and southeastern Mauritania. Its rise to power began in the 5th century when a group of chiefdoms in the Sahel grassland south of the Sahara formed a loosely knit kingdom under the leadership of the Soninke people, led by Diabe Cisse (c. 420-460 CE), who unified the Soninke in a loose federation to combat nomadic raiders and expand the kingdom.

Ghana’s growth was slow, with the kingdom expanding through the conquest of independent chiefdoms and kingdoms, which were then absorbed into the kingdom. At its peak in the early 11th century CE, Ghana had a powerful military with 200,000 soldiers and controlled a vast territory under the rule of its king, Basi (r. 1062-1082 CE). The kingdom’s wealth came from its strategic position in the trans-Saharan trade, where it exchanged gold, salt, and other commodities, with merchants such as those from the Islamic town of Awdaghost, which Ghana later conquered. However, Ghana’s control over the Bambuk goldfields, located far to the south, was tenuous. The chief of the nearest village had local authority over the mining area, and while Ghanaian rulers, such as King Tunka Manin (r. 1062-1082 CE), enforced a strict monopoly on gold nuggets above an ounce in weight, the difficulties of extracting and transporting the gold made their dominance precarious.

In the medieval Ghanaian kingdom, life was shaped by a dynamic blend of traditional African customs and Islamic influences, with distinct but complementary roles for men and women. Men largely controlled the trans-Saharan trade networks, facilitating the exchange of gold, salt, and other valuable commodities with Berber and Arab traders. Women, meanwhile, played an essential role in local commerce, managing markets and trading goods such as cloth, beads, pottery, and foodstuffs. While men were typically responsible for cultivating staple crops like millet, sorghum, and yams using time-honored farming techniques, women oversaw the processing, preservation, and preparation of these crops, ensuring food security for their communities.

Herding livestock—cattle, goats, and sheep—was another important aspect of the economy, and men traditionally took on this role, providing meat, milk, and leather for the community. The king, often regarded as semi-divine, ruled with the guidance of a council of male elders, but queen mothers and influential female spiritual leaders played key roles behind the scenes, especially in matters of succession and spiritual guidance.

Islam, introduced through trade around the 8th century, significantly influenced the kingdom’s culture, especially in architecture, education, and governance. However, Islam coexisted with indigenous spiritual traditions, and many people continued to observe traditional African religious practices, which often emphasized gender balance and complementarity. The kingdom of Ghana, at its height between the 9th and 11th centuries, was known for its rich cultural heritage, economic prosperity, and strong sense of community, with men and women contributing in distinct yet interconnected ways to the kingdom’s success.

During the eleventh century, the Ghana Kingdom faced significant challenges. While the Ghanaians welcomed Muslim traders, the emergence of radical Islamic sects in Morocco led to religious tensions and conflicts. The Almoravid movement, which arose among the Sanhaja people, established an kingdom centered in Morocco and captured the Islamic town of Awdaghost in 1055. This led to a period of religious strife and sectarian warfare, resulting in the Soninke Ghanaians’ conversion to Islam.

The twelfth century marked a transitional period for West African kingdoms. As Ghana expanded and faced conquests, new goldfields were discovered at Bure, and Soninke traders established new trade routes that bypassed the Ghanaian capital. This shift enabled southern Soninke and Malinke chiefdoms to assert their independence. By the early 1200s, the southern Soninke chiefdom of Sosso had gained control over much of former Ghana and the Malinke people, setting the stage for the Malinke struggle for independence and the eventual rise of the Mali Kingdom.

The Mali Kingdom

The Mali Kingdom rose to prominence in the 13th century, capitalizing on the decline of the Ghana Kingdom and the collapse of the Almoravid state in present-day Morocco. The Sosso Kingdom, a southern Soninke branch, briefly filled the power vacuum, but was defeated by Sundiata Keita (r. 1235-1255) in 1235. Sundiata, a Keita clan member, united the Mande kingdoms and defeated the Sosso invaders. He then founded the Mali Kingdom, expanding his territory and adding the Soninke people to his kingdom. This marked the beginning of a powerful and prosperous kingdom built on agriculture, trade, and gold. The leaders of the Mali Kingdom were given the title Mansa.

When Sundiata, the founder of the Mali Kingdom, tried to expand his kingdom, he faced resistance from gold producers. They did not want to be controlled by the kingdom and lose their independence. Sundiata’s successor, Mansa Musa (1307-1332), had a similar problem. The gold producers refused to submit to the kingdom’s authority, and when pressured, they would stop mining gold. To avoid losing access to gold, Musa let these areas remain mostly independent. The Mali Kingdom relied heavily on gold and trade. They controlled key trade towns like Oualata, Gao, Timbuktu, and Djenné, which connected them to the trans-Saharan trade. The kingdom’s economy was diverse, with different regions specializing in crops like sorghum, millet, and rice, while others focused on grazing animals.

The gold trade thrived under Musa’s rule. European demand for gold coins and new trade routes also contributed to the kingdom’s success. However, the kingdom’s rulers still had to balance their control over gold production with the need to maintain a stable gold supply. In 1324-1325 CE, Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage to Egypt and Mecca marked the peak of the Mali Kingdom’s prosperity. As the most renowned Malian king, Mansa Musa was known for his immense wealth. He led a massive caravan of 60,000 soldiers, 500 captives, and 100 camels loaded with gold into Cairo. The Egyptian sultan, a fellow Muslim, greeted Mansa Musa with great respect. During his visit, Mansa Musa generously distributed gifts, causing the value of gold in Cairo to plummet. The gold market did not recover for twelve years, a testament to the vast wealth of the Mali Kingdom under Mansa Musa’s rule.

Link to Learning

At the ARCGIS website, trace the caravan route of Mansa Musa (https://openstax.org/l/77MansaMusa) and consider the legacy of his pilgrimage to Mecca.

In Mali, life was characterized by a vibrant blend of Islamic and African traditions. Men controlled the lucrative trans-Saharan trade, exchanging gold, salt, and ivory, while women managed local markets, trading goods like cloth, grains, spices, pottery, and jewelry. Farmers, primarily men, cultivated crops such as millet, sorghum, and rice along the fertile lands of the Niger River, using agricultural techniques passed down through generations. Women played a vital role in processing, preserving, and preparing these crops for consumption, especially in rice production.

Herders, typically men, tended to cattle, goats, and sheep, providing essential resources like meat, milk, and leather for the community. Islamic scholars, primarily men, taught at esteemed centers of learning like the University of Sankore in Timbuktu, while women were key in preserving Mali’s oral traditions and cultural heritage through storytelling and song. Overall, life in medieval Mali was defined by a rich cultural heritage, economic prosperity, and a strong sense of community, with men and women contributing in distinct but interconnected ways to the kingdom’s success.

The Mali Kingdom’s prosperity relied heavily on its ruler’s leadership. However, during the late 14th century, a succession of weak rulers, short reigns, and internal power struggles left the kingdom vulnerable to conquest. As a result, the Mansas of Mali struggled to maintain control over the vital trade routes that sustained their power. The kingdom faced opposition from the Mossi people to the south, Tuareg attacks from the north, and regular uprisings by the Songhai people, who controlled the strategic city of Gao. These challenges forced Mali to abandon Gao and Timbuktu in 1438 CE. Additionally, the kingdom of Mema, once an ally of Sundiata, declared independence. Although weakened, Mali retained control over its core territory, the Mande heartland, and adjacent southern grasslands. Nevertheless, the emerging Songhai Kingdom, centered in Gao, began to dominate the lucrative trans-Saharan trade, posing a significant threat to Mali’s influence.

The Zimbabwean Plateau – the Kingdoms of Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe

During the Later Iron Age (c. 900-1600), Bantu migrants established several kingdoms in southern Africa, including Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe. These kingdoms shared linguistic and archaeological ties with the eastern Bantu subgroup.

Mapungubwe, which flourished from the 11th to the 13th century, is considered the precursor to Great Zimbabwe. It was southern Africa’s first state, with a complex economy based on livestock, agriculture, and trade. The people of Mapungubwe developed innovative farming techniques, including terracing hillsides to prevent soil erosion. They also engaged in gold mining, using forced labor to extract gold from the western plateau. Mapungubwe’s gold production led to a surge in local goods and trade, including gold ornamentation, ivory, and animal hides. The kingdom traded with the Swahili coast, exchanging goods for Indian glass beads, Chinese celadon pottery, and other luxury items. The social structure of Mapungubwe was class-based, with a sharp distinction between rulers and subjects. The royal complex, situated atop Mapungubwe Hill, featured stone enclosures, wooden palisades, and separate dwellings for the king, his wives, and district leaders.

Mapungubwe declined around the end of the 13th century, likely due to climate change, droughts, and soil degradation. As the land lost fertility, the population faced resource scarcity, leading to overpopulation and eventual decline. The center of medieval southern African civilization then shifted northward, giving rise to Great Zimbabwe, which owed a debt to Mapungubwe’s stone-building tradition.

Great Zimbabwe was founded by the Shona people, an Iron Age Bantu-speaking group that migrated to southern Africa around the 2nd century CE. The Shona established a thriving society, developing a mixed farming economy, mining and working iron, and trading with coastal settlements. By the 11th century, they had built drystone structures, including the Hill Complex, which may have served as a ritual or religious site. One of the earliest known rulers of Great Zimbabwe was King Masvingo (c. 1100-1130 CE), who oversaw the construction of the Hill Complex. Later, King Mutota (c. 1300-1320 CE) expanded the kingdom’s trade networks and built the Great Enclosure, which was completed during the reign of King Nyatsimba (c. 1320-1350 CE).

Link to Learning

Watch the video clip about Great Zimbabwe (https://openstax.org/l/77GreatZimb) titled “The City of Great Zimbabwe: Africa’s Great Civilizations,” and consider what the archaeological remains of Great Zimbabwe suggest about Zimbabwean culture and the organization of its society.

Great Zimbabwe flourished between the 13th and 16th centuries, with a hierarchical civilization of around 18,000 people ruled by an elite class or central authority. The society was male-dominated, with men competing for power based on cattle herd size. Status was largely determined by wealth, particularly in the form of cattle ownership. Men with large herds of cattle were considered wealthy and held high social status, while those with smaller herds or no cattle at all were considered poorer and held lower status. This wealth-based system was also tied to the number of wives a man had, as a large herd of cattle allowed a man to support multiple wives and their children. Additionally, wealth was also measured in terms of gold, ivory, and other luxury goods, which were obtained through trade and commerce. The ruling elite held immense wealth and power, while commoners had limited access to resources and social mobility. This system perpetuated social inequality, with the wealthy elite holding significant influence over the political and economic spheres of society. The government and society of Great Zimbabwe are not well understood, but it is believed to have been led by a chief or king who governed by consensus with leading male figures. One notable king was King Mwenemutapa (c. 1450-1480 CE), who expanded the kingdom’s borders and established trade relationships with the Portuguese.

Core Impact Skill — Intercultural Competence

The history of Great Zimbabwe helps us understand intercultural competence by showing how power, status, and cultural meaning are defined in ways that may be unfamiliar to us. Social rank in Great Zimbabwe was based not on titles or elections, but on wealth measured in cattle, gold, and the ability to support extended families. Religious centers like the Hill Complex and Great Enclosure held meaning that modern scholars are still working to interpret. Understanding this society requires us to set aside modern assumptions about gender, class, and governance—and to pay close attention to what mattered within their own cultural framework.

We learn about intercultural competence by studying how to interpret societies like Great Zimbabwe on their own terms. That means asking not how they compare to Western models, but how their structures reflect local values, relationships, and resources.

-

What challenges do historians face when trying to understand a society that left no written records—and how should that shape our approach?

-

How does learning about Great Zimbabwe help us question our own assumptions about what power, wealth, and legitimacy look like?

By studying the cultural logic of unfamiliar societies, we build the skill of recognizing difference without reducing it to deficiency. That’s at the heart of intercultural competence.

Women played vital roles in Shona society, particularly in agriculture, food preparation, and water collection. They were responsible for tending to crops, harvesting, and processing food for their families and communities. In addition, women managed the household, preparing meals and collecting water from nearby sources. They also played a significant role in beer production, which was an essential part of Shona culture and trade. Women’s agricultural expertise and knowledge of medicinal plants were highly valued, and they often served as healers and spiritual leaders. Furthermore, women’s economic contributions were crucial, as they were involved in trade and commerce, exchanging goods such as grains, vegetables, and crafts for other essential items. Despite their significant contributions, women’s social status was often tied to their relationships with men, and they held limited political power compared to their male counterparts. Nevertheless, women’s roles in Shona society were multifaceted and essential to the well-being and prosperity of their communities.

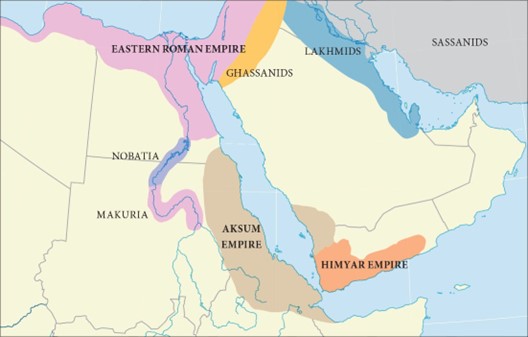

The Kingdom of Aksum

The Kingdom of Aksum flourished in sub-Saharan Africa from the first century BCE to the eighth century CE, emerging as a significant counterpoint to the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires. Strategically located in modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea, Aksum leveraged its proximity to the Red Sea to expand its territories across the sea into southern Arabia, establishing a brief but significant presence on the Arabian Peninsula. At its height from the third to the sixth century CE, Aksum was a powerful economic force, trading luxury goods like ivory, myrrh, and frankincense with Egypt, Arabia, and the eastern Mediterranean, with its currency, the Aksumite gold coin, widely accepted. The kingdom’s prosperity was further bolstered by its rich agricultural land, which supported a large population and enabled the Aksumites to build impressive architectural monuments, such as the Stelae of Aksum, showcasing a unique blend of African, Arabian, and Mediterranean influences in their culture and traditions.

Founded by King Zoskales in the 1st century BCE, Aksum rose to prominence under the rule of King Ezana in the 4th century CE, who expanded the kingdom’s borders through military conquests and established trade relationships with the Roman Empire. Ezana’s reign is also notable for the introduction of Christianity to Aksum, which became a central aspect of the kingdom’s culture and identity. The kingdom’s strategic location on the Red Sea made it a crucial hub for trade between the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean, with merchants like Cosmas Indicopleustes visiting Aksum in the 6th century CE.

In the ancient Kingdom of Aksum, daily life was shaped by a distinctive cultural fusion of African, Arabian, and Mediterranean influences. The population resided in stone and wood dwellings, with the affluent inhabiting grandiose villas featuring intricate carvings and sculptures that reflected the kingdom’s architectural prowess. As a major hub for trade, Aksum’s streets bustled with merchants and travelers from diverse corners of the ancient world, exchanging goods and ideas. Citizens engaged in various occupations, including agriculture, herding, and craftsmanship, with skilled artisans renowned for their exceptional textiles, pottery, and metalwork. The official language was Ge’ez, although Greek and Sabean were also widely spoken, facilitating communication among the kingdom’s diverse population. Aksumites practiced a syncretic mix of Christianity, Judaism, and traditional African religions, with rulers often depicted in art and literature as wise and powerful leaders. Despite social stratification, Aksum’s culture placed a high value on education, art, and architecture, fostering a sense of civic pride among its citizens.

During King Kaleb’s sixth-century reign, Christianity continued to thrive in Aksum, with churches becoming a ubiquitous feature in Aksumite cities, many of which were constructed during this period with inscriptions crediting Kaleb for his contributions. Aksumite churches typically followed Byzantine designs, with oblong shapes and rounded apses, although some featured unique circular plans possibly inspired by local house types. At its zenith, Aksumite society extended its cultural and political influence into southern Arabia, where Kaleb launched a military campaign against the Himyarite king Dhu Nuwas to support local Christian communities. This campaign was motivated by both Christian ideology and a claimed lineage to King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, leading to an alliance with the Byzantine emperor Justin to subdue Dhu Nuwas and establish Aksumite control over southern Arabia until the Sasanian conquest in 572.

Life in Aksum was marked by a unique fusion of African, Christian, and Mediterranean influences, with men and women playing distinct roles in the kingdom’s prosperity. Men dominated the kingdom’s vast trade networks, exchanging ivory, spices, and precious metals like gold and copper, while women were central to the production of textiles, pottery, and other crafts. Farmers, often men, cultivated crops such as barley, wheat, and teff (a small, gluten-free grain) using terracing and water management techniques, while women oversaw the processing and preparation of these crops for the community. Aksum’s strategic position enabled the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures with the Mediterranean and beyond, establishing the kingdom as a center of learning, art, and architecture, with men and women both contributing to its enduring legacy.

Aksum’s golden age began to decline in the 7th century CE, primarily due to internal factors such as political instability, economic strain, and environmental degradation. The kingdom’s extensive trade network, once a cornerstone of its prosperity, became increasingly difficult to maintain due to mismanagement and corruption. Meanwhile, the Aksumite monarchy faced challenges from regional nobles and rival claimants, further weakening the central authority. As the kingdom’s power waned, it became vulnerable to external influences. The last known king of Aksum, Dil Na’od (reigned c. 917-940 CE), attempted to revive the kingdom’s fortunes, but his efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, and the Aksumite Kingdom was eventually overtaken by the Zagwe dynasty, marking the end of an era.

Aksum’s legacy, however, endured in medieval Ethiopia, influencing the region’s cultural, religious, and architectural development. The kingdom’s rich cultural heritage, including its unique blend of African, Arabian, and Mediterranean traditions, continued to shape the identity of the Ethiopian people. The Aksumite architectural style, characterized by stone and wood structures, was adopted and adapted by later Ethiopian kingdoms, such as the Zagwe and Solomonic dynasties. Additionally, Aksum’s Christian traditions and liturgical practices were preserved and developed by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, which remains an integral part of Ethiopian culture to this day. Overall, Aksum’s enduring legacy is a testament to the kingdom’s significant impact on the history and culture of Ethiopia.

The Enduring Legacy of Medieval Sub-Saharan History

During the medieval period, African society underwent significant transformations across Sub-Saharan Africa, shaping the continent’s future. Starting in the 6th century CE, small communities of livestock herders and farmers grew into complex political entities. Innovations in agriculture and metalworking fueled growth in regions like the Niger River in West Africa and the Limpopo River in southern Africa. As trade expanded, local trade routes connected vast territories, driving the development of settlements and kingdoms.

The rich cultures, economic prosperity, and advanced civilizations of the Ghanaian, Malian, and Aksumite kingdoms challenge the long-standing myths that Africa was historically underdeveloped or disconnected from the rest of the world. These empires were thriving hubs of trade, innovation, and intellectual achievement, with extensive networks that linked them to Europe, the Middle East, and beyond. In Ghana, the wealth generated from the trans-Saharan gold trade supported a sophisticated society where men and women contributed to local and long-distance commerce. Mali, renowned for its prosperity under rulers like Mansa Musa, became a center of Islamic scholarship and culture, drawing scholars from across the Muslim world to its universities in Timbuktu. Aksum, with its unique blend of African, Greek, and Christian influences, emerged as a powerful kingdom known for its architectural marvels, such as the obelisks, and its control of vital trade routes between Africa, Arabia, and the Mediterranean. Together, these civilizations demonstrate Africa’s historical role as a major player in global trade and culture, disproving the narrative that African societies were isolated and primitive before European colonization.

Some kingdoms, such as Mapungubwe, were short-lived (lasting around 80 years), but they played crucial roles in medieval Africa’s development by linking it to distant peoples, places, and cultures. Other, more enduring kingdoms like Aksum had a lasting impact on the continent’s history. These medieval African kingdoms connected local economies to a vast network of trade and commerce that stretched across Europe, Asia, and Arabia. This exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures significantly shaped Africa’s cultural heritage and laid the groundwork for modern nation-states. The growth of trade and commerce during this time established the economic foundations for future prosperity in Africa, while the resilience and adaptability of medieval African societies prepared future generations to navigate challenges and opportunities.