11 The People of the Maghreb and Sahel

The Berbers, also known as the Amazigh, are a diverse group of people who played a crucial role in shaping the history of the Maghreb and Sahel regions (a vast area that includes modern-day Morocco, Algeria, Mauritania, Tunisia, Mali, and northern Niger). The term “Amazigh” is the name they use to refer to themselves, and it means “free people.” The Amazigh tribes were a diverse group of people, each with their own culture, language, and social structures. They were skilled traders and travelers, and their control of the trans-Saharan trade helped rise and fall of medieval African kingdoms and empires. After adopting Islam, the Amazigh became powerful empire builders, leaving a lasting impact on the region’s politics, economy, and culture.

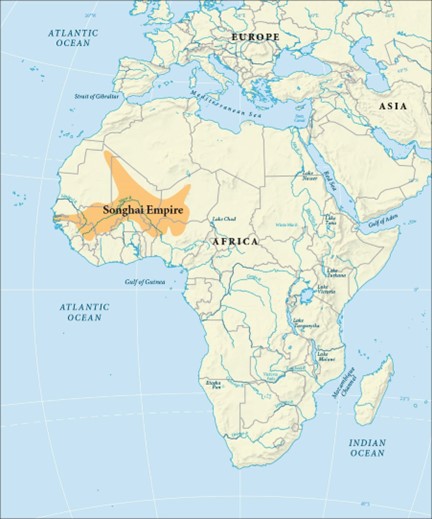

The Songhai Empire

In the seventh century CE, various groups inhabited the Middle Niger region (present-day Mali and Niger), including the Gabibi, Gow, and Sorko. Each group utilized the region’s resources differently, maintaining a balance with their environment. The Sorko, skilled warrior fishers and hunters, dominated the area and established trade routes along the Niger River. In the ninth century, nomadic horse-riding people speaking the Songhai language arrived, and the Sorko, Gabibi, and Gow adopted their language and culture. This fusion formed the basis of Songhai identity and the state of Songhai, with its capital at Kukiya. Gao, a trading city founded in the seventh century, became a crucial hub in the trans-Saharan trade. By the tenth century, Arab travelers noted its strategic location. As Gao grew, it relied on Songhai farmers and fishers for food, exchanging goods like salt and cloth. The rulers of Songhai converted to Islam in the eleventh century, marking the beginning of the Gao imperial period.

The Za dynasty, the earliest rulers of the Songhai state, is shrouded in myth and legend. They ruled during the eleventh and twelfth centuries, with the mythical founder Za Alayaman settling in Kukiya. The dynasty eventually adopted Islam, which became a central aspect of their kingdom’s identity and culture. The political focus shifted from Kukiya to Gao, which became a thriving center of trade, learning, and Islamic scholarship. As goods like kola nuts, dates, and gold passed through Gao, traders and merchants, including the Songhai, prospered. Gao’s prosperity attracted the attention of the expanding Mali Empire, which annexed it around 1325 CE. During this period, Gao flourished, and its trade networks expanded. However, the annexation was short-lived due to rebellions, civil war, and economic struggles.

The Songhai rebel leader, Sunni Ali (c. 1464-1492 CE), seized power and became the first king of the Songhai Empire. He embarked on a campaign of conquest, extending his empire deep into the desert and southwest. In Songhai oral tradition, Sunni Ali is remembered as a great general and conquering hero, as well as the founder of the Songhai Empire. The Songhai Empire’s strategic control of trade routes and urban areas, established during the reign of Sunni Ali and continued by his successors, enabled the kingdom to flourish and become even wealthier than Mali.

In the Songhai Empire, Islamic and African traditions actively shaped daily life. Women played significant roles in religious and social life, managing local markets and overseeing the production and trade of essential goods like food and cloth. Male merchants controlled the empire’s expansive trade networks, which connected the Sahara with the forests of West Africa, facilitating the exchange of gold, salt, and slaves. Songhai’s renowned universities, especially in Timbuktu, became centers of Islamic learning, attracting male scholars from across the Islamic world. Meanwhile, women played a crucial role in preserving oral traditions and the cultural heritage that sustained the empire’s sense of identity.

Cross-Culture Interactions in North Africa

In the seventh century, the Arabian Peninsula’s expanding Arab powers launched a campaign of conquest in North Africa. Egypt, a crucial hub of Coptic Christianity and Roman influence, fell to Arab armies around the mid-century mark. From there, Arab forces steadily advanced across the northern region, extending their control through military victories and strategic alliances.

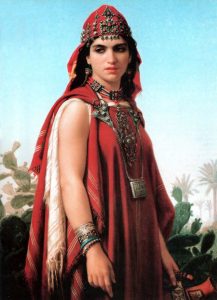

When Byzantine Carthage in North Africa succumbed to Umayyad armies in 698, Arab forces turned their attention to the Maghreb where Queen al-Kahina (also known as Dihya) rallied her people to oppose the onslaught. Al-Kahina, a 7th-century Berber queen, emerged as a formidable leader in the Maghreb, particularly in what is now modern-day Algeria and parts of Tunisia. Her rise to power coincided with the Arab conquest of North Africa, and she led a determined resistance movement, uniting various Berber tribes against the advancing Arab forces. Al-Kahina’s military skills and strategic acumen allowed her to secure several victories, temporarily halting the Arab advance. Although her leadership was predominantly focused on military resistance, her legacy endures as a symbol of Berber defiance and resilience. Despite the eventual success of the Arab conquest in the Maghreb, Al-Kahina’s resistance remains a testament to the enduring spirit and cultural heritage of the Berber people.

Core Impact Skill — Intercultural Competency

As you study the Arab expansion into North Africa in the 7th century, you encounter not only a story of conquest, but a deeper story of cultural resistance, adaptation, and memory. The Berber queen al-Kahina led a coalition of tribes to resist Arab forces advancing through the Maghreb. Though eventually defeated, her legacy lived on—not just as a military leader, but as a symbol of a people who refused to be erased.

We learn about intercultural competence by examining how the Berber peoples responded to Arab conquest—not only through military resistance, but also by negotiating their identity in a new cultural and religious landscape. The process was uneven and at times painful, but it reveals how communities can assert their values while engaging with powerful outside forces. Even when cultures collide under conditions of conflict, people find ways to preserve meaning, reinterpret faith, and carry memory forward.

-

How does al-Kahina’s leadership reflect the cultural values her people sought to protect?

-

What does the memory of resistance reveal about the long-term impact of cultural encounters?

-

How did Berber communities adapt to Islamic rule while maintaining distinct identities?

By studying the legacy of al-Kahina and the Arab-Berber encounter, we gain insight into how intercultural encounters are remembered, reinterpreted, and resisted—and how those processes shape the way cultures continue to relate to one another. That’s how we learn about intercultural competence.

Tensions simmered between Arab rulers and their African subjects, who were treated as second-class citizens despite their shared Islamic faith. Many Africans viewed themselves as more authentic Muslims than their elite Arab overlords, whom they saw as corrupted by power and luxury. They demanded the removal of cruel rulers and their replacement with pious leaders. This discontent boiled over into revolts that swept across North Africa in 739 and 740, shattering Arab control and fragmenting the region into various Islamic sects and ruling families. It would take nearly two centuries for North Africa to reunify under the rule of the Fatimids, a Shia Muslim dynasty that rejected the authority of the Abbasids, who had supplanted the Umayyads in 750 CE.

The Fatimids

The Fatimid Caliphate, a Shia Islamic dynasty, emerged in the 10th century, founded by Abdullah al-Mahdi Billah. Initially, they relied on indigenous African soldiers to conquer the Maghreb region. However, to challenge the Sunni Abbasid Caliphate, they diversified their army by recruiting Turkish soldiers, both free and enslaved. This strategy proved effective in the short term but ultimately led to ethnic tensions and a civil war in Egypt in the 1060s.

Despite their own experiences of persecution, the Fatimids practiced religious tolerance, allowing Christians, Jews, and Sunni Muslims to maintain their beliefs. They focused on spreading Shia Islam through education and the construction of mosques, such as Al-Azhar in Cairo. By the end of the 10th century, the majority of Egyptians had converted to Islam. The Fatimids’ religious tolerance was exemplified by the reign of Caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah (996-1021), who allowed Christians and Jews to hold high-ranking positions in government. For example, the Christian polymath Ibn al-Qifti (1172-1248) served as a high-ranking official under Al-Hakim’s successor, Caliph Al-Zahir li-i’zaz Din Allah (1021-1036).

This period of relative harmony was marked by significant cultural and scientific achievements. However, the Fatimids faced challenges in maintaining control over the Maghreb region, leading them to appoint Zirid governors, who eventually declared independence and aligned with the Abbasid Caliphate. The Fatimids attempted to reassert control by encouraging Arab migration, but this led to destructive wars and ultimately failed. Meanwhile, Christian crusaders captured Jerusalem in 1099, and the Fatimid Caliphate shrank to only Egypt. Internal power struggles in the 1160s further weakened the Fatimids, leading to a brief period of Christian protectorate. Eventually, a Sunni Muslim army led by Saladin (1137-1193) expelled the crusaders and pledged allegiance to the Abbasids, bringing Egypt back under Sunni control.

The Almoravids

In the mid-11th century, as the Fatimid Caliphate attempted to reassert control over the Maghreb, power shifted from the coastal regions to the Atlas Mountains in Morocco. This area was inhabited by the Sanhaja, a group of Africans comprising various ethnic tribes, including the Djuddala and Lamtuna. In 1039, Abdallah ibn Yasin (d. 1059) settled among the Djuddala at the invitation of Yahya ibn Ibrahim, who sought to reform the tribes according to his interpretation of Sunni Islam. Ibn Yasin spent over a decade imposing the Malikite school of Sunnism on the Djuddala, emphasizing a literal reading of the Quran and the sunna.

After his expulsion from the Djuddala, Ibn Yasin attracted followers from both the Lamtuna and Djuddala, forming the Almoravids. Under his leadership, in 1052 CE, they embarked on a campaign to defeat rival tribes and consolidate power, assembling a formidable army. By 1054 CE, they controlled the trans-Saharan trade route between Sijilmasa and Awdaghost. Following Ibn Yasin’s death in 1059, his followers continued their conquests, capturing Fez in 1069 and establishing Marrakesh as their capital in 1070 CE. The Almoravids then launched a series of military campaigns against the kingdoms of Al-Andalus, eventually conquering much of the Iberian Peninsula. From 1085, their empire, ruled by the Sanhaja, spanned from Tichitt (in modern-day Mauritania) to Zaragoza (in modern-day Spain), with Maliki legal doctrine dominating the region’s religious and legal landscape. Unlike the Fatimids, the Almoravids were intolerant of other faiths and interpretations of Islam, including Sufism and alternative Sunni sects. Their strict adherence to Malikism led to a decline in Quranic and sunna studies.

A rich blend of Islamic, Berber, and African influences profoundly shaped the lives of those living in the kingdom. The Almoravid’s strategic control over trans-Saharan trade routes brought significant prosperity through the trade of gold, salt, and ivory, although wealth was unevenly distributed, with the ruling elite and religious leaders holding considerable power. While the Almoravids adhered primarily to Maliki Sunni Islam, Sufism (a mystical less formal version of Islam) played an important role in everyday life, influencing both spiritual practices and community interactions. Sufi orders and mystics contributed to the kingdom’s cultural and religious life, offering a more personal and mystical approach to spirituality that resonated with many ordinary people. Their teachings and practices fostered a sense of community and provided a means for individuals to connect more deeply with their faith. Despite the prevailing social hierarchies, the Sufi emphasis on spiritual equality and communal bonds impacted the lives of many, contributing to the kingdom’s vibrant and diverse cultural landscape. Overall, life in the Almoravid kingdom was marked by a dynamic interplay of religious, economic, and cultural influences, with Sufism enriching the spiritual and communal experiences of its people.

The Almohads

The Almoravid dynasty was short-lived. Ibn Tumart (c. 1080-1130), a member of the Masmuda tribe from the Atlas Mountains in modern-day Morocco, led a countermovement against the Almoravids. Through his studies at mosques and madrasas across the Muslim world, Ibn Tumart developed a broader outlook than Ibn Yasin, challenging the latter’s scriptural literalism. He wanted to return to the pure and simple teachings of Islam, as taught by the Prophet Muhammad. He believed that the different groups of scholars who had developed their own interpretations of Islam had strayed from the original message. His followers, known as the Almohads, emphasized the transcendental unity of God.\

The Almoravid dynasty weakened due to internal conflicts and external pressures. Ibn Tumart’s Almohad movement gained momentum, and in 1147, they captured Marrakesh, the Almoravid capital. The Almohads then conquered the rest of the Almoravid territories, incorporating them into their own empire. The Almohads went on to conquer Muslim Spain, but their dominance was short-lived. Christian forces reconquered much of Spain by the mid-13th century, and the Almohad Empire faced internal rebellions and external threats, ultimately leading to its collapse in the 13th century.

Lasting Legacies: The Impact of the Fatimids, Almoravids, and Almohads

The Fatimids, Almoravids, and Almohads had a profound impact on the history of North Africa and the Mediterranean. These dynasties played a crucial role in shaping the region’s politics, culture, and trade. They founded vibrant cities like Cairo, Marrakesh, and Fez, which became hubs for learning, commerce, and art. Their legacy is evident in stunning architectural achievements like the Mosque of Al-Azhar in Cairo and the Koutoubia Mosque in Marrakesh.

Under the Fatimid dynasty, which ruled North Africa and Egypt from 909 to 1171 CE, ordinary people experienced a period of relative prosperity and cultural renaissance. The cities of Cairo and Kairouan emerged as vibrant centers of learning, art, and architecture, with thriving markets and trade routes that facilitated the exchange of goods and ideas. Merchants and artisans flourished, producing high-quality textiles, pottery, and metalwork that were renowned throughout the Mediterranean region. Meanwhile, farmers in the fertile Nile Valley and coastal regions cultivated crops such as wheat, barley, and dates, while fishermen harvested the abundant resources of the Mediterranean Sea. The Fatimid caliphs also invested heavily in infrastructure, building roads, bridges, and canals that further facilitated commerce and travel.

In contrast, life under the Almoravid and Almohad dynasties, which ruled the Maghreb and Spain from the 11th to the 13th centuries, was marked by greater austerity and militarization. The Almoravids imposed a strict interpretation of Islamic law, limiting cultural and artistic expression and emphasizing the importance of religious orthodoxy. Ordinary people focused on basic survival, with farmers and herders working hard to produce food in the harsh desert environment. The Almohads, who succeeded the Almoravids, continued this trend, prioritizing military conquest and religious purity over cultural and artistic expression. While cities like Marrakech and Cordoba remained important centers of trade and learning, the overall atmosphere was more somber and restrictive, with limited opportunities for social mobility or creative expression.

Despite the Almoravids’ and Almohads’ (11th–13th centuries) focus on strict religious orthodoxy and their limitations on cultural and artistic expression, Sufism offered a more personal and enriching spiritual path. During this time, Sufi orders like the Qadiriyya and Shadhiliyya emerged in the Maghreb, providing ordinary people with new avenues for spiritual connection. Influential Sufi mystics such as Abu Madyan (d. 1197) and Abdul Qadir al-Jilani (d. 1166) were celebrated for their teachings on love, compassion, and inner purification. Their ideas resonated deeply with the Berber population, merging with local traditions and creating a distinctive cultural and spiritual blend. This allowed people to experience a personal connection with the divine, even in an era marked by strict religious control. Consequently, Sufism enriched the region’s cultural life, impacting art, literature, and communal practices, offering a vibrant contrast to the otherwise restrictive and somber atmosphere of the period.

The Fatimids, Almoravids, and Almohads also had a major influence that reached well beyond their own territories. They played a key role in connecting Europe, Africa, and the Middle East by facilitating trade and cultural exchange. The Fatimids (909–1171) built a powerful empire that extended from North Africa to the Levant (the eastern Mediterranean region, including modern-day Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Lebanon, and parts of Syria and Turkey), with cities like Cairo becoming important centers of trade and learning. The Almoravids (1040–1147) and Almohads (1130–1269) continued this trend by controlling crucial trade routes across the Sahara Desert, which allowed goods such as gold, salt, and ivory to flow between Africa and the Mediterranean. This integration of trade routes helped link the economies of these regions and contributed to a more connected medieval Mediterranean world.

The impact of these dynasties also shaped the political landscape of North Africa. Their territorial boundaries and administrative systems influenced the development of modern countries like Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Egypt. The governance practices established by the Fatimids, Almoravids, and Almohads, such as tax systems and legal codes, laid the foundation for contemporary national institutions. Although these dynasties eventually declined, their legacy is still visible today. The cultural and political identity of North Africa continues to be shaped by their historical contributions to trade, governance, and cultural exchange.