24 China in the 14th and 15th Centuries CE

The Mongol Empire’s disintegration had far-reaching consequences for China, accelerating the decline of Mongol dominance in East Asia. By the second half of the 13th century, the Yuan dynasty faced numerous challenges. Emperor Kublai Khan (1215-1294) had engaged in several costly and unsuccessful military campaigns against neighboring kingdoms, including Burma, Annam, Champa, and Java. Additionally, two attempts to invade Japan had failed, and resistance movements against Mongol rule were emerging across the empire. One of the most significant of these movements was the Muslim resistance in Quanzhou (1357-1367), a major port city in southeastern China.

Quanzhou was a cosmopolitan city, home to over two million people, including foreign-born merchants from Arabia, Persia, India, and other regions. Despite their significant economic and cultural contributions to the city’s prosperity, the Muslim community in Quanzhou faced discrimination and persecution under the Yuan government. In 1357, the Muslims of Quanzhou launched a resistance movement against the Mongols, seeking to end the oppressive policies and restore their rights and freedoms. The movement, which lasted until 1367, was a key challenge to Mongol authority in the region. The attempts to suppress such movements, combined with Kublai Khan’s unsuccessful military campaigns, severely drained the treasury and weakened the empire. His successors often mismanaged the empire’s resources and held power for only brief periods, leading to further instability.

Concurrently, natural disasters, including droughts, floods, and epidemics, exacerbated the suffering in China, fostering discontent and the rise of religious sects and secret societies predicting the end of Mongol rule. One such group was the Red Turban movement (1351-1368), a popular uprising with roots in the White Lotus Society, a Buddhist secret society. The Red Turbans were driven by millenarian beliefs, which foretold the end of the Yuan dynasty and the restoration of Chinese rule. Their movement ultimately led to the rise of the Ming dynasty, which brought an end to Mongol rule in China in 1368.

Early Ming Emperors

Hongwu, also known as Zhu Yuanzhang, was the founder and first emperor of the Ming dynasty, ruling from 1368 to 1398 with the title Taizu of Ming. As the first Ming emperor, Hongwu sought to establish a strong and stable government after the collapse of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. He implemented various policies to consolidate his power, protect himself from threats, and reassert Chinese influence.

Hongwu’s reign was marked by significant efforts to centralize authority and eliminate potential threats. He abolished the position of chief minister to rule without interference, established a secret police force to monitor and eliminate dissent, and executed thousands of perceived opponents. His administration swiftly crushed rebellions, including a revolt by the Miao ethnic group in Hunan Province and the Kingdom of Dali in Yunnan Province. In 1387, Ming forces invaded Manchuria, defeating Mongol loyalists and incorporating the region into China. To secure borders in underpopulated areas, Hongwu made military service hereditary and forcibly relocated peasants from the south to central and northern China.

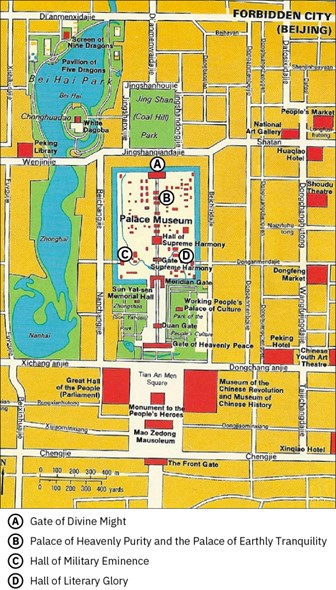

Hongwu’s successor, Zhu Di (the Yongle emperor), continued to expand Chinese power. From 1406 to 1427, Chinese forces attempted to invade Vietnam and counter the Mongol threat, leading to the repair and extension of the Great Wall. However, Zhu Di diverged from his father’s isolationist policies, seeking to establish relations with foreign lands to showcase China’s wealth and power. He dispatched Admiral Zheng He on seven naval expeditions between 1405 and 1433, visiting Southeast Asia, India, Arabia, and East Africa. Zheng He presented foreign rulers with gifts and returned with tribute, establishing diplomatic relations with rulers in the Philippines, Indian Ocean, and Central Asia. Zhu Di also moved the capital to Beijing, constructing the Forbidden City and an elaborate tomb, both of which symbolized China’s power, wealth, and magnificence.

Core Impact Skill — Persuasion

The reign of the Yongle Emperor (Zhu Di) illustrates how persuasion can project power beyond military strength, shaping both domestic authority and international relations. Succeeding his father, the Hongwu Emperor, Zhu Di inherited a stable but inward-looking Ming dynasty. Departing from his father’s isolationist tendencies, he combined military action—such as campaigns in Vietnam and defensive projects like repairing and extending the Great Wall—with grand displays intended to convince both his subjects and foreign rulers of China’s wealth, stability, and rightful place as a global power.

We learn about persuasion by studying how Zhu Di used monumental architecture, ceremonial display, and diplomatic outreach to influence audiences. The construction of the Forbidden City in Beijing and his elaborate imperial tomb symbolized dynastic strength, order, and divine legitimacy. Abroad, he commissioned Admiral Zheng He to lead seven massive naval expeditions between 1405 and 1433, sending fleets to Southeast Asia, India, Arabia, and East Africa. These voyages, backed by the sheer scale of China’s ships and the lavishness of imperial gifts, persuaded foreign rulers to enter tributary relationships and acknowledge the Ming Emperor’s supremacy. At home, such achievements reinforced Zhu Di’s image as a ruler who could expand China’s prestige while safeguarding its borders. Persuasion here was more than words—it was embodied in stone, ceremony, and spectacle, appealing to pride, loyalty, and mutual benefit.

-

How did Zhu Di combine military action, monumental architecture, and diplomatic display to persuade both domestic and foreign audiences of his legitimacy and power?

-

What does the success of Zheng He’s voyages reveal about the role of spectacle and material display in shaping international relationships?

By examining Zhu Di’s reign, we see how persuasive leadership can work through symbols, infrastructure, and orchestrated encounters—shaping political order at home and projecting influence far beyond a nation’s borders

In Ming China prior to 1500 CE, ordinary people engaged in various occupations to make a living. For instance, farmers in the Yangtze River Delta cultivated rice and mulberry trees, relying on advanced irrigation systems and crop rotation techniques to maximize yields. In contrast, artisans in the city of Jingdezhen specialized in crafting porcelain, using techniques like underglaze blue and white decoration to create intricate designs, which were then exported to Southeast Asia and beyond. Additionally, merchants in the city of Hangzhou traded goods like silk, tea, and salt, while skilled laborers worked as carpenters, building intricate wooden structures like temples and pagodas. These occupations demonstrate the diversity of economic activities in Ming China, where people worked hard to support themselves and their families.

At the same time, the lives of ordinary people were governed by a rigid social hierarchy and strict gender roles. Men were expected to assume roles as farmers, artisans, or merchants, while women were relegated to domestic duties, managing the household and raising children. The societal expectations placed on women were particularly restrictive, with limited access to education and no rights to own property or participate in public life. Women were expected to submit to the authority of their fathers, husbands, and sons, and were often subjected to the painful practice of foot binding, a symbol of beauty and modesty. By the 14th and 15th centuries, foot-binding was a common practice, especially among the upper classes. It was seen as a symbol of beauty, status, and feminine virtue. The practice involved tightly binding young girls’ feet to prevent them from growing, resulting in the so-called “lotus feet,” which were considered desirable and a marker of social status. In contrast, men enjoyed greater freedom and opportunities, but were also burdened with responsibilities to their families and communities. Despite these strict roles, women from affluent families could occasionally access education and wield influence within their households, while men from lower classes faced significant economic and social challenges. Overall, life in Ming China was characterized by a patriarchal system that limited opportunities and choices for women, while men held power and authority.