23 The Mongol Empire

In the late 12th century, the vast Eurasian steppe was inhabited by numerous clans and tribes, each with their own leader and social hierarchy. Clans were the basic unit of steppe society, consisting of several families that shared resources and responsibilities. These clans often joined forces to form tribes, which were loosely organized and open to anyone willing to obey the leader. However, these alliances were short-lived, and clans frequently switched allegiances. The region was marked by constant raids and turmoil, exacerbated by settled peoples like the Jin and Song, who often pitted nomadic groups against each other. This volatile environment ultimately led to the rise of a powerful Mongol-led confederation, which would eventually unite under Genghis Khan and go on to create the vast Mongol Empire.

The Rise of Temujin

The rise of this powerful Mongol-led confederation was largely due to the emergence of a skilled and charismatic leader, Temujin, who would eventually take the title Genghis Khan. Born around 1162, Temujin was a member of the Borjigin clan, which had been prominent in the region for generations. However, his early life was marked by hardship and struggle, including the murder of his father and the subsequent abandonment of his family by their clan. This tumultuous beginning would shape Temujin’s worldview and inform his future conquests, as he sought to create a more stable and unified steppe society through military campaigns and strategic alliances.

The life of Temujin, later known as Genghis Khan, before his rise to power is shrouded in mystery, with no historical records available. The most reliable source, “The Secret History of the Mongols,” was likely written after his death and is based on oral traditions. According to this account, Temujin’s early life was marked by hardship and struggle. He was briefly enslaved by a rival clan, but escaped with the help of a sympathetic family. Later, his wife Borte was kidnapped by the Merkit tribe, and Temujin formed an alliance with Ong Khan to rescue her. Upon her return, Borte gave birth to a son, whose paternity was uncertain, but Temujin accepted him as his own. In the early 1180s, Temujin broke away from his friend and clan leader Jamukha, forming a new clan with himself as leader, marking the beginning of his rise to power.

Temujin revolutionized traditional Mongol practices, driven by his own experiences with hardship and struggle. As he expanded his military campaigns, he addressed social class differences by punishing resistance leaders and executing rival clan leaders, while sparing common people and integrating them into his army. He prohibited indiscriminate looting and rape, instead focusing on capturing or killing fleeing warriors to prevent future retaliations. Temujin put captured aristocrats on trial, executing them for their alleged wrongdoings, and divided the spoils equally among his soldiers and the families of fallen comrades. This ensured that widows and orphans were protected, reducing desertion.

Temujin reorganized his warriors into units of ten, hundred, and thousand, bound by oaths of loyalty, with leaders chosen based on merit and loyalty. This innovative structure created a deadly fighting force, unified diverse ethnic and linguistic groups under his rule, and provided a shared role in society for all males. Temujin’s reforms sparked a division in steppe civilization, with aristocrats fearing him and commoners seeking protection and rewards. Rival leaders, such as Ong Khan, who led the Kereit tribe, and Jamukha, a childhood friend turned rival, opposed Temujin’s vision and allied against him. After Ong Khan’s failed attempt to trap Temujin, he fled to a secret gathering point known as the Baljuna Covenant (located in present-day Burkhan Khaldun, Mongolia), where his top leaders reaffirmed their loyalty to him through a sacred oath, pledging to stand together against their enemies. This covenant became a powerful symbol of Mongol unity and loyalty, uniting people from nine clans and four religions under a shared commitment to Temujin’s leadership. The call went out to regroup and find Temujin, solidifying his new nation, known as the “People of the Felt Walls” (a name referring to the nomadic Mongol people who lived in portable felt-lined tents, or “gers”), and cementing his position as their leader.

In 1206, Temujin convened an unprecedented kurultai, a meeting of loyal leaders and people, to confirm his rule over all Mongols. Nearly a million People of the Felt Walls attended, setting up encampments for miles, making it a highly inclusive event. A shaman proclaimed him Chinggis Khan, confirming Tengri’s grant of authority and blessing his people with prosperity and good fortune if he governed wisely and fairly. To prevent succession conflicts and maintain the democratic spirit, Chinggis Khan decreed that future great khans could only be chosen by a kurultai, not familial succession. He established rules, known as the yassa, to govern household relations and later ordered the development of a written Mongol script to record the yassa and other important documents, solidifying his position as the leader of the “great Mongol nation” and unifying the diverse tribes under his rule.

Focus on Persuasion

Temujin’s ascension to power as Chinggis Khan offers profound insights into effective leadership, particularly in the realm of persuasion. By convening the kurultai, an inclusive gathering of leaders and constituents, Temujin demonstrated the value of collaborative decision-making and stakeholder engagement. His merit-based approach to leadership, eschewing traditional hereditary succession, underscores the importance of recognizing and rewarding talent and dedication. Moreover, Temujin’s ability to articulate a shared vision and forge a collective identity among his people, as embodied in the concept of the “great Mongol nation,” highlights the persuasive power of compelling communication. Through Temujin’s leadership, we learn that building consensus, empowering others, and communicating a clear vision are essential skills for persuading and inspiring others to work towards a common goal.

In Temujin’s Mongol society, traditional gender roles shaped family life. Women were crucial in managing household duties, raising children, and caring for animals. Men were responsible for providing for their families through hunting, warfare, and leadership. Despite these roles, Mongol women enjoyed more autonomy and respect compared to many other ancient societies. They could own property, participate in religious ceremonies, and even serve as shamans. Temujin’s mother, Hoelun, was a significant influence on his early life and exemplified the strength and resourcefulness of Mongol women. His wife, Borte, also played an important role, serving as a trusted advisor and contributing to his political and military efforts. While gender roles were present, they were not strictly rigid, allowing for flexibility and mutual support within families. This balance between traditional roles and adaptability contributed to strong family bonds, social cohesion, and the Mongols’ military success.

Expansion and Growth

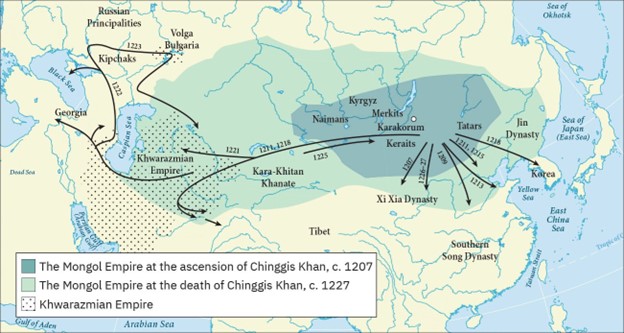

The Mongols’ conquest of China was a gradual process that began in the early 13th century CE. Initially, Genghis Khan sought to establish trade relations with the Jin dynasty in northern China, but tensions escalated when the Jin emperor refused to acknowledge Mongol authority. In 1211, Genghis Khan launched a military campaign against the Jin, exploiting the dynasty’s internal weaknesses and divisions. The Mongols effectively utilized their mobile cavalry and siege warfare tactics, which were particularly effective against the Jin’s reliance on static defenses and fortifications. As the Jin dynasty weakened, the Mongols formed alliances with defecting Jin generals and capitalized on regional rivalries, ultimately capturing the Jin capital, Zhongdu (modern-day Beijing), in 1215.

The Mongol conquest of China was a complex and multifaceted event that had both positive and negative consequences. On one hand, the Mongols brought about significant destruction, displacement, and loss of life, particularly during the initial invasions. They also imposed their own administrative systems, laws, and social hierarchies, which could be harsh and exploitative. On the other hand, the Mongols also facilitated cultural exchange, trade, and economic growth. They established a vast network of trade routes, known as the Silk Road, which connected China to Central Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. This led to the exchange of ideas, technologies, and goods, enriching Chinese culture and economy. Additionally, the Mongols promoted religious tolerance, allowing Buddhism, Daoism, and Islam to flourish in China.

Following the conquest of northern China, Genghis Khan turned his attention to Central Asia, conquering modern-day Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and parts of Afghanistan between 1219 and 1224. He then launched a campaign against the Khwarezmid Empire in present-day Iran, Azerbaijan, and parts of Turkey, defeating the Khwarezmid Shah in 1221. The Mongols continued their westward expansion, invading Eastern Europe and defeating combined Russian and Ukrainian forces at the Battle of the Sit River in 1238. Meanwhile, Genghis Khan’s generals expanded the empire’s borders in the east, conquering the Tanguts in modern-day Gansu and Ningxia provinces of China. By the time of Genghis Khan’s death in 1227, the Mongol Empire stretched from the Pacific Ocean to the Caspian Sea, covering a vast territory of over 24 million square kilometers. He died during a campaign against the Western Xia dynasty in modern-day China, and his burial site remains a secret to this day. His successor, Ogedei Khan, continued the empire’s expansion, but the Mongols’ territorial gains began to slow as they faced increased resistance and internal power struggles.

Ogedei Khan, a son of Genghis Khan, held power from 1229 to 1241. During his reign, the empire reached its peak size and strength. Ogedei built on his father’s achievements by streamlining the empire’s administration and governance. He introduced a system of provincial governance that enabled more effective management of the vast territories. Under his leadership, the Mongols launched successful military campaigns, including the invasion of Eastern Europe and the conquest of the Khwarazmian Empire, expanding Mongol influence into new regions.

Ogedei’s rule also saw significant advancements in trade and diplomacy. He developed and promoted the Silk Road trade routes, fostering cultural and economic exchanges between East and West. His policies encouraged the blending of cultures and administrative practices within the empire. However, his rule faced challenges, including internal conflicts and logistical difficulties in managing the vast empire. Ogedei Khan’s death in 1241 CE marked the end of an era of Mongol expansion, as his successors struggled to maintain the empire’s unity and manage its sprawling territories.

Ogedei’s greatest achievement was the establishment of the Pax Mongolica, or Mongol Peace, which united a vast portion of the world through the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures. This unprecedented era of peace and stability was achieved through a dual approach: on one hand, the Mongols imposed a strict code of justice and tolerance on the territories under their control, allowing for the free flow of people, goods, and ideas; on the other hand, they decisively dealt with opposition, making it clear that submission to their rule was the most advantageous option. Through this combination of firm governance and economic incentives, the Mongols created a vast network of trade routes, known as the Silk Road, which facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures between East and West. The Pax Mongolica was funded by a system of taxation, where all producing people contributed to the empire’s coffers, allowing for the maintenance of a vast and efficient administrative system. As a result, many recognized that cooperation with the Mongols was the best choice, leading to a period of unprecedented peace and prosperity that lasted for over a century.

The Empire Ends

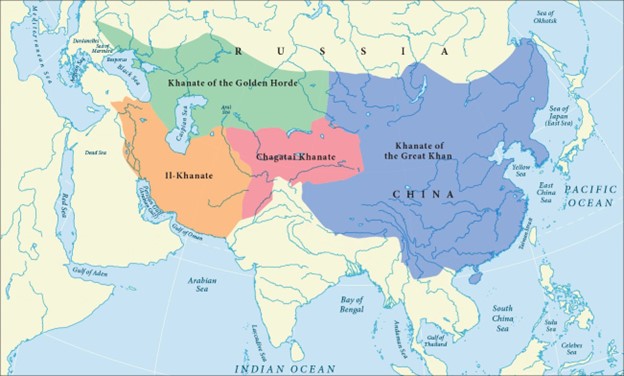

After Ogedei’s death in 1241, the Mongol Empire was plagued by a succession crisis. His son, Guyuk, eventually succeeded him, but his reign was short-lived and marked by power struggles. Guyuk’s death in 1248 led to a further decline in central authority, as various Mongol khanates and nobles began to assert their independence. The empire was eventually divided into four main khanates: the Yuan in China, the Golden Horde in Russia, the Ilkhanate in Persia, and the Chagatai Khanate in Central Asia. This fragmentation weakened the empire’s overall cohesion and led to a decline in its military prowess.

The Mongol Empire’s decline was further accelerated by internal conflicts, regionalism, and external pressures. The Black Death, which spread across the empire in the 14th century, also had a devastating impact on the Mongol population. As the khanates continued to drift apart, the empire’s trade networks and administrative systems began to break down. By the 14th century, the Mongol Empire had largely disintegrated, and its various khanates were eventually absorbed into other empires or became independent states. Despite its decline, the Mongol Empire’s legacy continued to shape global politics, culture, and trade for centuries to come.