36 Europe in the Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages, spanning the 14th and 15th centuries, was a pivotal time in European history. As the fervor of the Crusades diminished and the feudal system began to decline, Europe faced unprecedented challenges. The Black Death, which swept through the continent from 1346 to 1353, decimated nearly a third of the population, leading to significant social, economic, and cultural upheaval. The rise of city-states, nation-states, and powerful monarchies transformed the political landscape, while the Papacy’s authority faced challenges from the Conciliar Movement. Additionally, the Hundred Years’ War between England and France, along with the Ottoman Empire’s expansion into Eastern Europe, further destabilized the region. Despite this turmoil, cultural and intellectual innovations thrived, as seen in the works of figures like Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio, paving the way for the Renaissance. The Late Middle Ages set the stage for Europe’s transition to the Early Modern era, characterized by a revival of classical learning, the growth of nationalism, and the beginning of a new global age.

The 14th Century

The Catholic Church in Europe, once a pillar of stability in the 13th century, faced significant turmoil in the 14th century. Tensions between the Pope and national monarchs weakened papal authority and divided the Church. A notable clash occurred between Pope Boniface VIII and King Philip IV of France over the taxation of clergy. Boniface asserted papal supremacy, which led to Philip’s attempted kidnapping in 1303, demonstrating the escalating conflict between spiritual and temporal powers. Although the papacy maintained autonomy, its spiritual prestige diminished during its subsequent relocation to Avignon, France, where it remained from 1309 to 1377. This period, often referred to as the Avignon Papacy, saw the Church become more entangled in political matters, further alienating many Christians and leading to a perception of the papacy as a tool of French interests.

The Great Western Schism (1378-1417) further eroded papal authority, as rival factions within the Church disputed the legitimacy of competing popes. This division began when the election of Pope Urban VI sparked controversy, leading to the election of an opposing pope in Avignon, thus creating a split that caused confusion among the faithful. Eventually, three simultaneous claims to the papacy emerged, further undermining the Church’s moral standing across Europe. The Council of Constance (1414-1418) eventually resolved the crisis by electing Pope Martin V, but the papacy’s reputation had already suffered irreparably. Satirical works, such as “The Land of Cockaigne,” reflected the growing disdain for the clergy, depicting a monastery made of pastries and breads, symbolizing greed amid widespread food insecurity. Such critiques of clerical excess resonated with the populace, revealing the deepening divide between the Church and ordinary Catholics.

The 14th century was marked by political and military conflict, particularly the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453) between England and France. The war erupted over English claims to French lands, exacerbated by the death of King Charles IV of France without a male heir. This conflict saw widespread devastation across France, as battles raged and cities were besieged, leading to significant loss of life and property. Additionally, the war contributed to factionalism within both kingdoms, as nobles and commoners alike chose sides. Military technology advanced during this period, with the introduction of the English longbow and early firearms significantly altering the dynamics of warfare. Although England initially dominated the early stages of the conflict, France ultimately emerged as western Europe’s dominant kingdom by 1453, marking a turning point in the balance of power.

Link to Learning

The British Library learning timeline (https://openstax.org/l/77Timeline) provides an interactive chronology including brief descriptions, sources, and images of key events in fourteenth-century European history, such as the Hundred Years’ War.

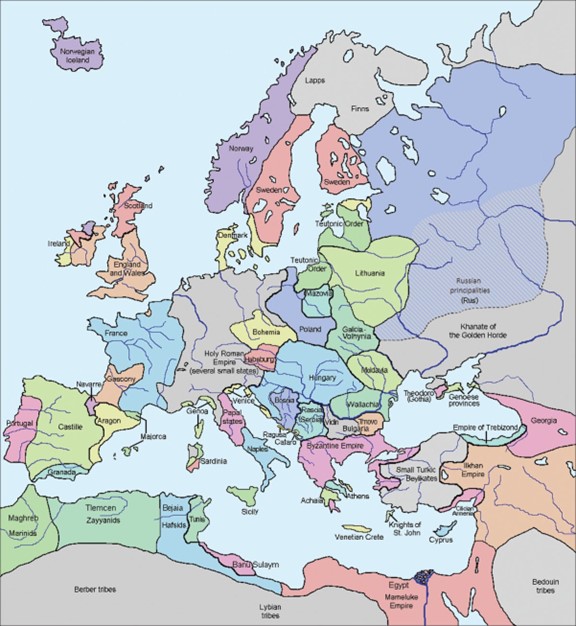

Another center of political instability during this period was the Holy Roman Empire. In the fourteenth century, the Holy Roman Empire, which had been founded by Charlemagne in 800, comprised four main entities—the Kingdom of Italy, the Kingdom of Germany (including lands that now are part of Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, and Switzerland), the Kingdom of Burgundy (a region in southeastern France), and the Kingdom of Bohemia (what is now the Czech Republic and part of Poland) under the nominal control of an elected emperor. Each of these kingdoms, in turn, was composed of a loose coalition of independent territories with different hereditary rulers. The emperor was chosen by a handful of these rulers known as electors.

Competition between noble families vying for the role of emperor often created instability. In 1314, for example, one group of electors chose the ruler of Austria to be emperor, but another group gave the title to the ruler of Bavaria. Later in the century, the Golden Bull, proclaimed by the emperor Charles IV in 1356 (bull is the Latin word for “seal”), attempted to simplify and clarify the process by which the emperor was elected. The document asserted that emperors would be selected by seven specific prince-electors, the secular rulers of four principalities and the archbishops of three cities within the empire. This practice of electing emperors stood in stark contrast to the hereditary monarchies of other European kingdoms such as France and England.

Rather than adopting a common currency, legal system, or representative assembly, the Holy Roman Empire remained a patchwork of semi-autonomous principalities. Although each of these became relatively stable, the empire itself was a weak and decentralized political entity. By the end of the fourteenth century, it included more than one hundred principalities, each with varying degrees of power and autonomy. The emperor was now beholden to both the rulers who elected him and the pope, who in theory bestowed the imperial crown.

Amidst these tumultuous changes, the 14th century also witnessed profound social transformations. The devastating impact of the Black Death (1346-1353), which decimated nearly a third of Europe’s population, altered societal structures and relationships. Labor shortages led to increased bargaining power for surviving workers, challenging the traditional feudal system and contributing to the emergence of a more market-driven economy. As the Catholic Church grappled with the aftermath of the plague, public dissatisfaction grew regarding its ability to provide spiritual and physical solace during such crises. This era of hardship and upheaval laid the groundwork for significant shifts in religious, political, and social landscapes, setting the stage for the transformative events of the Renaissance and Reformation that would follow in the subsequent centuries.

The Little Ice Age

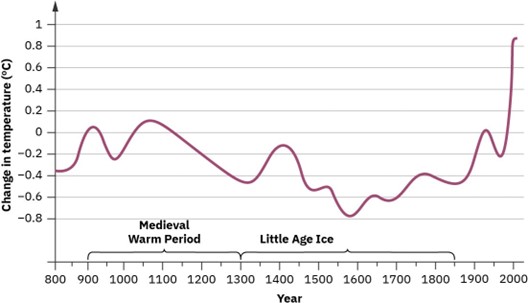

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, subtle shifts in global mean temperature and rainfall had a profound impact on the climate of the Northern Hemisphere, unleashing devastating famines and plagues across Afro-Eurasia. These events caused significant human hardship, disrupted commerce, and contributed to the decline of once-great empires. In an era during which many people survived on subsistence agriculture, even the slightest change in seasonal weather patterns could devastate crops and result in widespread malnourishment and starvation. Poor nutrition weakens human immune systems, which—together with poor sanitation and the close quarters in which people lived in medieval towns—undoubtedly left many more vulnerable to the ravages of epidemic diseases. This was especially the case when the bubonic plague struck much of Afro-Eurasia by the middle of the century.

In the fourteenth century in particular, the Little Ice Age, a period of unusually cold weather that affected most of the Northern Hemisphere, led to significant variations in normal rainfall and a general drop in the mean annual temperature. Preceded by a Medieval Warm Period, a span of more temperate climate across the globe from the tenth through the thirteenth century, the cool temperatures and, in some areas, droughts radically reduced available resources and food supplies. Aggravated by rising population levels and declining agricultural productivity, food shortages caused significant hardship and financial distress as famine became commonplace and competition for resources intensified.

Although the Little Ice Age was especially devastating in the 1300s, its effects persisted for many centuries. In addition to its immediate impact on crops, late medieval climate change led to longer-term deforestation because more wood was used for heating, in the Northern Hemisphere in particular. The climate shift not only altered building designs and clothing styles, which became adapted to colder temperatures, but in some places it also ultimately precipitated the eventual adoption of coal for heating and the beginning of human reliance on fossil fuels.

Learn More

Listen to the podcast, “The Little Ice Age: Weird Weather, Witchcraft, Famine and Fashion,” discussing the historical climatology of the Little Ice Age (https://openstax.org/l/77LittleIceAge) and its connection with some of history’s most critical events, such as the Black Death and the French Revolution.

The period known as the Great Famine of 1315–1317 was a direct result of the Little Ice Age in much of Europe north of the Alps, an area of roughly 400,000 square miles. This widespread and prolonged food shortage prompted one of the worst population collapses in Europe’s recorded history. It is virtually impossible to know the actual death toll, but it is likely that up to 10 percent of northern Europe’s population of more than thirty million perished. Even though crop yields began to rebound in 1317, it took several more years for them to return to prefamine levels. Beyond the devastating loss of lives and human suffering, prolonged food shortages also led to widespread political and economic instability. The prices of necessary food staples like grain skyrocketed, and competition for resources generated social tension, conflict, and an increase in crime. Ultimately, the Great Famine led many to question the ability of church officials and monarchs to respond effectively to crises and catastrophes, which had long-term effects on public trust in these institutions.

With very few options to remedy the devastation wrought by years of poor weather and famine, most people had little practical recourse other than migrating in search of better conditions. The collective anxiety and social tension of the era sometimes led to scapegoating, including persecutions of supposed witches based on the premise that they had the ability to control the weather as a means of causing others harm. Historians have traced connections between peaks of the Little Ice Age and spikes in witch-hunting activities. Although this type of persecution was by no means universal, it demonstrates the desperation many people must have felt in the face of unrelenting strife.

The Black Death

The bubonic plague, the most common variant of the disease caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, raises egg-shaped swellings known as buboes near an afflicted person’s lymph nodes in the groin, underarm, and upper neck areas. Other symptoms include fever, nausea, vomiting, aching joints, and general malaise. For the vast majority in the Middle Ages, death generally occurred within three days. The bubonic plague pandemic, which had far-reaching economic, political, social, and cultural effects throughout Afro-Eurasia, came to be known as the Black Death. This name, inspired by the blackened tissue the disease caused on the body, also came to express the fear and awe brought by a disease with a mortality rate ranging from 30 to 80 percent.

That is significantly higher than the deadliest smallpox, influenza, and polio pandemics of the modern era. Although in its bubonic form the plague could not be spread from human to human, the rat flea became a major plague vector, an organism that spreads plague from one organism to another.

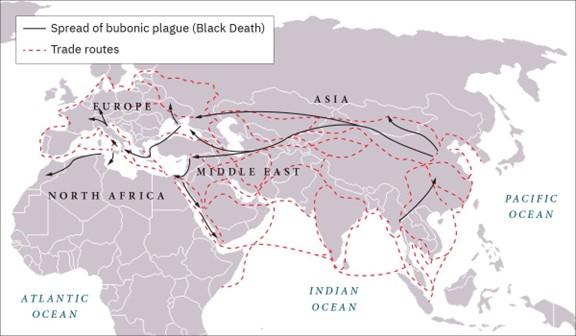

The black rat was one of the most capable animal hosts for the plague-carrying fleas. It was highly susceptible to the disease itself and an especially inconspicuous stowaway on trade caravans and merchant ships. Cases of bubonic plague proliferated as rats spread through the international shipping and trades routes of the Silk Roads and the Mediterranean Sea, where they colonized crowded dwellings in towns and cities. The spread of the plague only increased owing to the increased movement of people. First it was the Mongol armies, traveling over enormous distances and unintentionally bringing small mammalian stowaways among their foodstuffs. Then, owing to the Mongols’ protection of merchants and others traveling great distances during the Pax Mongolica, the disease spread further and in new directions. Finally, those forced to leave their homes for survival amid famine and environmental change created yet another pathway for the disease to spread.

Plague-bearing fleas generally preferred to feed on small rodents such as rats and marmots, but when their rodent hosts succumbed to the plague, they secured their next meal from the nearest human. Two even deadlier variants of the disease eventually emerged during the fourteenth century: pneumonic and septicemic. The pneumonic form directly infected the lungs and was spread from person to person by coughing, with a mortality rate of 95 to 100 percent. The septicemic variant, which resulted from plague bacteria circulating directly into the bloodstream, was invariably fatal and, according to contemporary observers, seemed to kill within hours of the first onset of symptoms. While historians had surmised for many decades that the plague had spread in primarily one form (bubonic) and in one direction (east to west), new evidence increasingly suggests there was a far greater diversity of spread.

Although in many regions where it struck the plague was eventually understood to be contagious, at first the means of transmission were not recognized. Some saw the epidemic as a divine punishment from God, and others speculated that it was caused by a rare conjunction of planets creating noxious atmospheric conditions on Earth. Others blamed foreign travelers, minority religious communities, or vagrants. The desperation incited by the plague’s relentless assault often led to scapegoating of marginalized populations, particularly in Europe.

The Plague its way to the ports of Europe via Silk Roads trade caravans and merchant ships sailing the Black Sea in 1346–1347. After striking the Mongol-controlled cities of Astrakhan and Sarai (in present-day Russia), when bales of flea-infested marmot fur were unloaded, the plague then traveled down the River Don, where it reached the city of Caffa (present-day Feodosiya, Ukraine), a center of trade on the Crimean Peninsula. From Caffa, the plague made its way to Italy in the summer of 1347, when plague-bearing rats boarded ships headed across the Black Sea, through the Dardanelles, and onward to the ports of Messina and Genoa. From there, the disease was carried to the port of Marseilles and spread into the European interior along rivers, paths, and roads, leaving perhaps as many as twenty-four million dead, roughly 30 percent of the continent’s population at the time.

The plague’s arrival in Europe occurred after a period of economic contraction following a series of famines and crop failures earlier in the fourteenth century. In the early 1300s, a rising population and a relative decline in agricultural productivity had created an economic crisis and falling standards of living for all but the most privileged elites. For the vast majority of people living at the lower end of the economic spectrum, falling wages led to limited resources, poorer diets, and widespread malnourishment. Well before the plague’s arrival in the 1340s, the European population was reeling from years of economic decline and poor nutrition, which may have weakened immune systems and made some people more vulnerable to attacks of infectious disease.

In addition to the demographic and economic impacts of the Black Death era, modes of artistic and literary expression were significantly transformed in response to the plague’s devastation. In the visual arts, the fears engendered by the omnipresence of death and decay initiated a new emphasis on realism that grappled with themes of salvation and mortality. Macabre representations of deathbed scenes and dancing skeletons became especially prominent reminders of the inevitability of death and fears of hell and damnation Although the visual iconography of death reflected the collective cultural trauma associated with the plague, it also served as a potent reminder to celebrate life in the face of it.

Medieval writers also sought to make sense of the Black Death by documenting the experience of living through the pandemic and exploring themes of transience and mortality. For example, in Giovanni Boccaccio’s famous collection of novellas, The Decameron, a fictional group of young men and women taking refuge from the plague in a villa outside Florence pass the time by trading stories that reflect upon love, loss, and the vagaries of fortune. The Decameron also calls attention to larger social responses engendered by the plague’s demographic devastation, such as the growing prominence of merchants due to the continued growth of global trade and people’s loss of confidence in the European Christian Church.

Link to Learning

Some of the stories that make up Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron (https://openstax.org/l/77Decameron) can be read at the Project Gutenberg website.

Although the Christian Church remained a bastion of spiritual solace for many during the Black Death, social responses to the plague in medieval Europe ranged from increased piety to hedonism to resigned acceptance of inevitable death. Those who could afford to do so fled the crowded urban centers, but most did not have this luxury. Medieval European cities remained hotbeds of infection despite the efforts of some Italian cities to impose quarantine and travel restrictions. Some cities even closed markets and prohibited gatherings for funerals; others required the removal of the infected to plague hospitals. Lacking a germ theory of contagion, however, medical practitioners were unable to fully explain or remedy the plague, although centuries of early scientific observations led many to attempt the techniques and approaches that had served in outbreaks of other diseases. Failing to fully grasp how and why the disease was spreading, however, many of the devout turned to the clergy, who were also dying in record numbers, mostly because of their efforts to care for the sick. But they too were unable to prevent the plague’s relentless toll.

While some blamed the plague on earthquakes, astrological forces, or poisonous fog, most people in Christian Europe agreed it was a sign of God’s displeasure. In some towns, the belief that communities had to be purged of “morally contaminating people” such as prostitutes and beggars also led to the scapegoating of Jewish people, who were falsely accused of causing the plague by poisoning wells. Regardless of the fact that their communities also suffered from the plague, Jewish people faced widespread persecution, escalating in several cities to full-blown massacres. Driven by the fire-and-brimstone dogmatism of late medieval Christianity, those who led the persecution of marginalized populations sought to placate God by building churches, developing cults to plague saints like Saint Roche, and hunting heretics and outsiders they believed had provoked divine displeasure.

The desperation and zealotry that inspired some responses to the plague in medieval Europe are perhaps best seen in the appearance of flagellants, people who believed that by publicly flogging themselves, they could atone for the sins of humanity and mitigate divine retribution. After this idea originated in Eastern Europe and took root in Germany, the flagellants traveled from town to town, reciting penitential verses and lashing themselves with leather whips until they drew blood. They were usually welcomed by townspeople who hoped they could bring an end to the plague epidemic. Occasionally, their rhetoric took an anti-Semitic turn, accusing the Jewish people of causing the plague to annihilate Christendom. The flagellants were active through much of Europe in the early years of the plague pandemic and may have even spread the disease through their contaminated blood. As a result of their increasingly radical orientation, however, by 1349 flagellants had been officially condemned by Pope Clement VI, and they ultimately faded into oblivion in the fifteenth century.

Core Impact Skill — Persuasion

The Black Death in medieval Europe reveals how persuasion can shape collective responses to crisis—sometimes inspiring solidarity and reform, and at other times fueling fear and persecution. While some leaders promoted public health measures such as quarantines, market closures, and restrictions on gatherings, the absence of a clear medical understanding left many to seek meaning in religious explanations. Clergy, despite suffering high mortality rates themselves, urged repentance and moral reform, framing the plague as divine punishment. This framing persuaded many to support church building, the veneration of plague saints, and campaigns against those deemed morally corrupt.

We learn about persuasion by studying how religious and civic leaders channeled fear into action—whether through penitential rituals, charitable works, or scapegoating marginalized groups. Flagellant processions, for example, persuaded communities that public acts of self-punishment could secure God’s mercy. Their dramatic displays drew crowds and inspired imitation, but also spread anti-Semitic rhetoric that contributed to massacres of Jewish communities. In this way, persuasion operated as a powerful but dangerous tool: it could mobilize people toward shared goals, yet also justify violence and exclusion.

-

How did religious leaders use persuasive appeals to frame the plague as a moral and spiritual crisis rather than a purely medical one?

-

What does the case of the flagellants reveal about the potential for persuasive movements to inspire both hope and harm in times of desperation?

By examining these responses to the Black Death, we see how persuasive communication in moments of crisis can influence immediate actions, reshape community priorities, and leave lasting marks on cultural memory.

The plague left each region it affected with long-term economic and demographic consequences, including widespread depopulation and cyclic outbreaks of the disease in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Old systems of belief came into question, and ancient social hierarchies shifted to accommodate the significant population losses that followed the plague. Peasants, laborers, and those at the lower end of the socioeconomic hierarchy tended to experience the greatest mortality, but for those who survived, pronounced labor shortages led to the demise of some industries and more favorable working conditions in others. The disadvantaged began to question whether social elites really did enjoy God’s privilege, as the social hierarchy generally preached, since they too succumbed to the plague and failed to care for those to whom they bore responsibility.

Learn More

Learn how the experience of infectious disease can be different depending on a variety of factors, especially access to wealth, by reading this article from TheConversation.com. Learn about the similarities and differences between the Black Death pandemic in the fourteenth century and the COVID-19 global pandemic in the modern world.

Just as political entities and empires broke down or evolved over the course of the fourteenth century, so too did the social structures and hierarchies that defined much of the medieval period, especially in western Europe. In many medieval cities, the merchant class began to acquire increasing wealth and power, while in the countryside the political and social pyramid known as feudalism began to weaken. Feudalism had been defined by a small elite group of hereditary landowners governing the lives of the peasants known as serfs who worked their lands. In exchange for the privilege, serfs paid rent in the form of labor, which generally kept them tied to the land in servitude with little income to spare. This dependent relationship began to disintegrate, however, in the wake of the Great Famine, Black Death, and Hundred Years’ War.

Given massive depopulation and the loss of resources they needed to survive, people increasingly chose to leave locations to which they had formerly been anchored. Peasants left the feudal estates on which their families had lived for generations, as landlords elsewhere offered more generous terms of labor to attract workers who could replace the dead. Many peasants also left the countryside to seek wage labor and employment in cities, which began experiencing significant labor shortages as a result of the plague’s staggering death toll. Because the demand for labor was so high, peasants who remained in the countryside, especially males, were now able to press their employers for more money and rights.

In towns, where labor shortages were also a problem, rules requiring guild membership for artisans seeking to practice their crafts were often relaxed, making it easier for newcomers to engage in craft production. Guild masters often responded to the need for labor by shortening the time that apprentices had to serve, which may have helped to attract willing young men to their shops. The same masters, however, often changed the rules of their guild so that only the sons and sons-in-law of current masters could become masters themselves. The enterprising peasant might thus be able to find an apprenticeship in a trade, but he would not be able to advance to the highest level and become an independent master or the employer of others.

Emboldened by the shift in power and angered when the nobility attempted to limit their economic opportunities, peasants launched rebellions that further damaged the foundations of feudalism by calling into question the lords’ traditional privileges. These popular revolts, such as the Jacquerie (a French word for a particular type of garment that came to be associated with peasants and peasant uprisings) of northern France in 1358 and the English Peasants’ Revolt of 1381, included not only peasants but also merchants, craftspeople, and other common people. Although the landowning elites ultimately prevailed in most of these clashes, their role was changing rapidly. With fewer people to work their land and generate income for them, their collective wealth contracted significantly. The power of local nobles and landowners was also being eclipsed by more powerful monarchs and emerging urban economies that bolstered the growth of towns and cities.

In addition, the death of many members of the clergy during the Black Death made monarchs more dependent on the merchant class to perform services for which education was required. The rising prominence of the merchant class that resulted, coupled with the growing centralization of monarchical power, gradually eroded some of the traditional privileges and prerogatives of landed elites. Although some regions of the continent, particularly the German lands of the Holy Roman Empire, remained a largely decentralized and fragmented collection of principalities, by the end of the fourteenth century, England and France had begun to lay the foundations of the centralized modern nation-state to replace the power of the nobles.

Another impetus for the rise of centralized monarchies and the reduction of the nobility’s authority was the Hundred Years’ War. This conflict not only reinforced budding notions of national identity, but it also changed the nature of warfare and minimized the nobles’ traditional military role as expensively trained and outfitted cavalry officers. The use of new weapons and tactics rendered the cavalry-focused armies of the feudal era all but obsolete, because large professional standing armies paid for by monarchs could defeat mounted knights with the use of the longbow. Thus, the new type of warfare chipped away at the traditional feudal prerogatives and prestige of social elites. The growth of professional armies also offered peasants the potential for social mobility, because they were able to earn a regular wage for military service while also sharing in the spoils of war.

Ultimately, the combination of depopulation, shifting military practices, and centralization of monarchical power led to the demise of feudalism. Although profound social disparities persisted in the wake of its decline, increased opportunities for social mobility and the emergence of centralized monarchical bureaucracies began to erode the feudal divide between commoners, serfs, nobles, and the wealthiest landowners.