13 Populating the Americas

The peopling of the Americas is a complex and still-debated topic. While scientific evidence suggests that Homo sapiens arrived in the Americas around 20,000-15,000 years ago, Native American communities have long maintained that they have always been here, with their own distinct cultural and spiritual traditions. This perspective highlights the importance of considering multiple narratives and knowledge systems when understanding the history of the Americas.

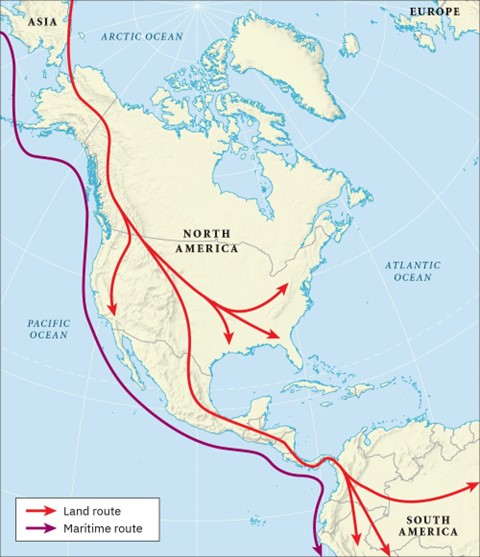

The most widely accepted scientific theory is that humans crossed into the Americas via the Beringia land bridge, which connected present-day Alaska and Russia during the last ice age (around 25,000-11,000 years ago). As the glacial ice retreated, humans began to spread southward into the Americas, traversing a corridor between two melting ice sheets and expanding in waves across the continental United States. Some groups reached the western coast, while others migrated to the northeast, southeast, and central regions, eventually reaching modern Mexico, Central America, and South America. By around 15,000 years ago, human populations had established themselves in various parts of the Americas, although the exact timing and migration routes are still being researched and debated.

Native American communities have their own rich and diverse origin stories, which often emphasize their deep spiritual connection to the land. For example, the Ojibwe people believe they originated from the St. Lawrence River valley, where the Creator placed them at the beginning of time. The Navajo people have a complex origin story involving the emergence from multiple underworlds, ultimately leading to their arrival in the Four Corners region. Similarly, the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest believe they were created from the land itself, with their ancestors emerging from the earth, rivers, and mountains. These stories highlight the importance of place, spirituality, and community in Native American cultures, and underscore the significance of considering indigenous perspectives when exploring the history of the Americas.

First Peoples

The Clovis culture, dating from around 13,500 to 12,800 years ago, is widely recognized as one of the earliest well-documented Paleoindian cultures in North America. However, the absence of archaeological evidence does not mean that other cultures did not exist before or alongside Clovis. Indigenous peoples have their own rich and diverse histories, which stretch back thousands of generations and emphasize a deep spiritual connection to the land. In fact, many Native American communities have oral traditions and stories that speak to a much deeper history in the Americas, one that predates the Clovis culture. Archaeological evidence of Clovis culture has been found in various states, including Texas, Virginia, and Oregon, as well as in Central and South America, but it’s essential to consider this evidence within the broader context of Native American experiences.

Watch and Learn

Discover Native American origin stories through a series of short videos produced by PBS, available on this website.

The Clovis people hunted a variety of megafauna, including mammoths, mastodons, and giant bison, as well as smaller game. They fished in coastal waters, lakes, and rivers, and settled in areas with reliable access to fresh water and resources. Archaeologists have discovered burial sites with red ocher, suggesting spiritual beliefs. The extinction of megafauna, which occurred around the same time as the Clovis culture, is still debated, with both overhunting and climate change considered contributing factors.

The Clovis culture eventually gave rise to various regional cultures, which developed during the Archaic period (around 8,000 to 1,000 BCE). These groups adapted to diverse geographical settings, including the Pacific Northwest, Great Plains, Eastern Woodlands, Southwest, Mesoamerica, and South America. They developed unique cultural practices, reflecting their response to environmental conditions. This period saw the emergence of various cultural traditions that would shape the Americas, including the development of more complex societies and eventually, the rise of civilizations.

Peopling the Pacific Northwest

In the Pacific Northwest, the abundant marine life and dense forests supported the growth of complex hunter-gatherer societies. These societies thrived on a variety of resources, with salmon being a crucial food source due to its annual upstream migration, which provided a reliable opportunity for capture and preservation. Other essential food sources included beaver, elk, seals, birds, sea lions, and various fish species like halibut. The region’s landscape also offered materials for toolmaking, such as bone, rocks, and trees, which they used to create harpoons, woodworking tools, and canoes.

The abundance of resources in the Pacific Northwest allowed settled groups to accumulate wealth more easily than many other hunter-gatherer societies. This led to the development of complex societies where wealth and social status were intertwined. Archaeological evidence from burial sites around 2000 BCE suggests that wealth contributed to social differentiation, with the graves of the wealthy containing carved antler tools and shell objects. Over time, these graves included increasingly more objects indicative of higher social status, and evidence of high population density in certain areas suggests that the abundant food resources supported a larger population. The indigenous nations of the Tlingit (present-day Southeastern Alaska and Northwestern British Columbia) and Haida (present-day Haida Gwaii, an archipelago off the coast of British Columbia, Canada), among others, trace their ancestry to these ancient societies and continue to thrive in the region, maintaining their cultural heritage and traditional ways of life.

Peopling the Great Plains

In the vast Great Plains region of North America, indigenous peoples hunted massive bison herds that roamed the grasslands. Unlike the animals hunted by the Clovis people, bison adapted to the warming climate and thrived in the plains. The groups that followed and lived off the bison developed a seminomadic lifestyle, requiring minimal belongings and resulting in less social stratification compared to the Pacific Northwest. Archaeological evidence reveals that around 8000 BCE, hunters employed strategies like driving bison herds over cliffs or cornering them to facilitate spear hunting.

In addition to bison, plains peoples hunted antelope, deer, and small game like rabbits and birds. The indigenous nations of the Lakota (present-day South Dakota and North Dakota) and Cheyenne (present-day Montana and Oklahoma), among others, thrived in this region. They utilized animal hides for clothing, and edible plants like seeds, berries, and tubers were also staples in their diet. People carried and stored food in coiled plant baskets or leather bags, showcasing their resourcefulness and adaptability in the Great Plains environment.

Peopling the Eastern Woodlands

To the east of the Great Plains lie the Eastern Woodlands, a region of lush forests and abundant waterways stretching from the Mississippi River basin to the Atlantic coast. The indigenous peoples of this region, such as the Wampanoag (present-day Massachusetts) and the Iroquois (present-day upstate New York), found a diverse array of plants and animals to sustain themselves. The numerous rivers, lakes, and oxbow lakes provided fresh water and excellent hunting and fishing grounds for various species. Edible plants, including nuts from oak, chestnut, and beech trees, were also plentiful. Near coastal areas, saltwater marine life was an additional source of food.

As populations rose around 6500 BCE, people began to construct large earthworks, such as Watson Brake in northern Louisiana, which dates back to around 3900 BCE. These earthworks, often featuring human-made mounds, were likely used on a seasonal basis by hunter-gatherers. The discovery of large cemeteries, including those in Illinois and Tennessee, reveals an increasingly sedentary lifestyle and rising populations. Some sites contain the remains of over a hundred individuals, often with personal items like weapons and art, showcasing a more complex societal structure.

Peopling the American Southwest

In the arid Southwest, indigenous peoples adapted to the harsh desert environment, developing innovative irrigation systems to cultivate crops like corn, beans, and squash. Ancestors of the Akimel O’odham (present-day Arizona) and Taos Pueblo (present-day New Mexico) were among the peoples that thrived in this region. They built multi-story dwellings, known as pueblos, using stone and adobe materials, and developed a rich spiritual tradition centered on the land and their ancestors. The Southwest’s diverse landscape, from mesas to canyons, also provided a variety of resources, including game animals, edible plants, and mineral deposits.

As populations grew, Southwestern peoples developed more complex societies, with specialized labor, social hierarchies, and trade networks extending across the region. The ancient city of Chaco Canyon in northwestern New Mexico, dating back to around 800 CE, is a testament to this complexity, featuring elaborate road networks, ceremonial buildings, and sophisticated astronomical observatories. The discovery of artifacts like pottery, weavings, and turquoise jewelry reveals a rich cultural heritage, while the presence of ball courts and kivas (ceremonial chambers) speaks to the importance of ritual and spiritual practices in Southwestern societies.

Peopling California

California, the most populous region of indigenous North America, was home to a diverse array of people-groups, each with their own distinct culture and traditions. The Ohlone (present-day San Francisco Bay Area) and the Miwok (present-day Sierra Nevada foothills) were among the many Nations that thrived in this region, which offered a mild climate, abundant food sources, and access to the Pacific coast. California’s indigenous peoples developed complex societies, with specialized labor, social hierarchies, and trade networks extending across the region. They built sturdy homes, like the Ohlone’s tule houses, and developed a rich spiritual tradition centered on the land, animals, and ancestors.

The region’s diverse landscape, from coastal redwood forests to desert oases, supported a wide range of resources, including acorns, salmon, and game animals. California’s indigenous peoples developed innovative tools, like the mortar and pestle, to process these resources and created beautiful works of art, like basketry and shell jewelry. With estimates suggesting that California was home to over 300,000 indigenous people before European contact, it is clear that this region was a hub of cultural, economic, and spiritual activity. The legacy of California’s indigenous peoples continues to shape the state’s identity and cultural heritage today.

Peopling Mesoamerica

In Mesoamerica, a region encompassing present-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras, indigenous civilizations developed sophisticated societies and cultivated crops such as maize, beans, and squash. Archaeological evidence reveals that these ancient peoples inhabited coastal sites along the Gulf of Mexico and Pacific Ocean, as well as the Tehuacán Valley. They lived in small groups, adapting their subsistence strategies to the seasonal availability of resources. During the dry season, they relied on wild game and plants like agave, while in the rainy season, they enjoyed a diverse array of fruits, nuts, and small game. The Zapotec (present-day southern Mexico) and Maya (present-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras) are among the indigenous nations that trace their ancestry back to these early Mesoamerican settlers.

Excavations at El Riego Cave in the Tehuacán Valley, occupied around 8000 BCE, have uncovered sophisticated stone tools, woven baskets, and elaborate burials, indicating a complex spiritual practice. By 5000 BCE, the settlers’ diet shifted from wild game to domesticated plants like beans, squash, and maize, which was selectively bred from the wild grass teosinte. This domestication process led to increased yields and softer kernels. By 2600 BCE, agriculture became a dominant practice, with groups cultivating maize, beans, and squash, marking a significant transition from gathering to farming. Maize, in particular, became a staple crop, facilitating population growth and the development of more complex societies.

Link to Learning

Learn more about the history of the domestication of Maize by reading this article: The Amazing Journey of Maize.

Peopling the Andes Mountains Region

The Andean region, which spans present-day Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Chile, has been home to diverse human populations for thousands of years. The indigenous nations of the Quechua (present-day Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Argentina) and the Aymara (present-day Peru, Bolivia, and Chile) developed sophisticated agricultural systems, harnessing the fertile soils and favorable climates to cultivate crops like maize, potatoes, and squash. The Inca Empire, which rose to power in the 15th century, is a notable example of the complex societies that developed in this region.

The Amazon rainforest, covering much of present-day Brazil, Peru, and Ecuador, has been inhabited by numerous indigenous groups for thousands of years. These groups, such as the Tupi (present-day Brazil) and the Ashaninka (present-day Peru), developed complex societies and cultures adapted to the unique environment of the rainforest. They cultivated crops like manioc and sweet potatoes, and developed sophisticated knowledge of the forest’s medicinal and spiritual properties.

The Southern Cone, which includes present-day Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay, has also been home to diverse indigenous populations for thousands of years. The indigenous nations of the Mapuche (present-day Chile and Argentina) and the Guarani (present-day Paraguay, Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay) developed complex societies and cultures adapted to the region’s varied environments, from the Andes mountains to the Pampas grasslands. They cultivated crops like maize and squash, and developed sophisticated knowledge of the region’s natural resources.

The Neolithic Revolution in the Americas

The Neolithic Revolution in the Americas was a gradual and regionally diverse process that unfolded over millennia. In the Andean region, early forms of agriculture and animal domestication began around 8000 BCE. The Quechua and Aymara peoples domesticated llamas and alpacas for their meat, wool, and labor, and cultivated plants like squash, potatoes, and quinoa. These early farmers lived in small villages, using new tools and techniques to manage their crops and animals. As their food supply increased, populations grew, leading to more permanent settlements.

In Mesoamerica, people began domesticating corn (maize) from the wild grass teosinte around 5000 BCE. This development significantly impacted agricultural practices and societal organization, leading to population growth and the rise of more complex societies. Early evidence of maize cultivation has been found in the Tehuacán Valley and the highlands of Oaxaca. As farming replaced hunting and gathering, people settled in permanent villages, developed social hierarchies, and established trade networks that increased efficiency and productivity.

By around 2000 BCE, maize farming had spread to the southwestern United States. Indigenous peoples in this region adapted maize to their arid environment, developing irrigation systems to support their crops. This agricultural shift allowed for the growth of larger communities and more complex societies, with maize becoming a staple food source that significantly influenced local diets.

In the Eastern Woodlands, people had been experimenting with the cultivation of edible plants like sunflowers, squash, and gourds for thousands of years. Around 2000 BCE, they began to clear larger areas of land for farming, leading to increased food production and population growth. The earliest evidence of farming in the Eastern Woodlands comes from the Ohio River Valley. As farming became more widespread, people settled in more defined territories, traded goods with neighboring groups, and developed complex social structures.

In California, the Neolithic Revolution did not involve widespread maize farming. Instead, the peoples of this region relied on a diverse range of plants, such as acorns, nuts, and seeds, to sustain their societies. They developed extensive trade networks, exchanging goods like shells, beads, and obsidian over long distances. Evidence of early farming in California has been found in the Sacramento Valley and the San Joaquin Valley.

In the Pacific Northwest, the Neolithic Revolution took on a different form. Although people in this region continued to rely heavily on hunting and gathering, they also developed complex societies. They built large wooden houses, established rich cultural traditions, and engaged in long-distance trade, exchanging goods like copper, shells, and fur. The Pacific Northwest did not adopt maize farming, instead relying on local plants like camas and berries.

By around 2000 BCE, the gradual adoption of farming had transformed life across the Americas. Populations grew, societies became more complex, and new social structures, including social hierarchies and trade networks, began to emerge. The shift to agriculture laid the foundation for the civilizations that would arise in the centuries to come, deeply influencing the cultural and economic landscape of the continent.

Core Impact Skill — Perspective-Taking

The Neolithic Revolution in the Americas was not a single moment or universal pattern—it was a gradual and diverse process that unfolded differently across regions. From the Quechua and Aymara in the Andes to the farmers of the Eastern Woodlands and the foraging societies of the Pacific Northwest, Indigenous communities made decisions based on their environments, values, and knowledge systems.

Practicing perspective-taking means learning to see those decisions from the inside—not just asking what changed, but why. Why did some groups adopt maize, while others focused on acorns or seeds? Why did some prioritize irrigation while others built trade networks across mountain passes and river valleys? Understanding early agricultural societies on their own terms helps us respect the diversity of Indigenous experiences and challenge assumptions about what development, complexity, or success looks like.

-

🔍 What does the regional diversity of the Neolithic Revolution reveal about how Indigenous communities defined success and survival?

-

🧠 How can looking at agriculture, trade, and settlement through Indigenous perspectives help us rethink ideas like “progress” or “civilization”?

Perspective-taking reminds us that the past holds many ways of living and organizing society. By listening to those voices, we gain the skills to better understand—not judge—worldviews that differ from our own