15

In the Americas, ancient civilizations flourished for thousands of years, leaving a rich cultural legacy. The Inca and Aztecs built powerful empires in the Andes and Mesoamerica, drawing on the heritage of earlier cultures like the Moche, Nazca, and Tiwanaku, and the Olmec, Maya, and Teotihuacanos. Similarly, the Mississippian tradition chiefdoms developed from the mound-building traditions of Adena, Hopewell, and earlier cultures in the Eastern Woodlands. In the Southwest, the Ancestral Pueblo peoples built complex societies, harnessing the region’s resources and cultivating sophisticated knowledge systems. The peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, including the ancestors of the Tlingit and Haida, developed vibrant cultures, renowned for their artistic and trading traditions. In the Great Plains, various nomadic and semi-nomadic groups thrived, their traditions closely tied to the region’s vast herds of bison. The peoples of the Northeast and Great Lakes regions, including the ancestors of the Huron and Algonquin, developed complex societies, marked by sophisticated agricultural practices and intricate networks of trade and diplomacy.

The Aztec Empire

The Aztecs rose to prominence following the decline of the Toltec civilization, which had dominated central Mexico from the 10th to the 12th centuries CE. As the Toltecs waned, various nomadic groups, including the Aztecs, moved into the region and engaged in fierce conflicts. By around 1325 CE, the Aztecs settled on islands in Lake Texcoco and began constructing their capital city, Tenochtitlán (teh-noh-chee-TLAHN). After acquiring some influence in the region, they formed an alliance with two neighboring city-states, Texcoco and Tlacopan. Then, in 1428, this Triple Alliance launched a surprise attack on the powerful city-state of Atzcapotzalco and made itself the dominant regional power. Over the next several decades, the Triple Alliance, with the Aztecs at its head, expanded its control of central Mexico to include Oaxaca in the west, parts of modern Guatemala in the south, and the areas bordering the Gulf of Mexico. By 1428 CE, they had overthrown the powerful city-state of Atzcapotzalco and emerged as the dominant force in the region.

At its height, the empire consisted of thirty-eight provinces, each expected to submit specific tribute to the imperial capitals. Occasionally, regions that resisted incorporation into the empire were given harsh terms. More often, the type of tribute demanded was related to the location of the tribute state and the goods it typically produced. For example, the Gulf coast area was known for natural rubber production and was assessed a tribute payment of sixteen thousand rubber balls for use in the Aztec ball game. Locations much closer to the capitals commonly provided goods like food that were expensive to transport over long distances. Those much farther away might be expected to provide luxury goods the Aztec elite gave as gifts to important warriors. Typical tribute items included cloth, tools like knives and other weapons, craft goods of all types, and of course, food. Tribute items could also include laborers to work on larger imperial projects. The Aztec tribute system functioned much like a crude system of economic exchange. Goods of all types flowed into the centers of power and the hands of elites. But they also made their way to commoners, who benefited from the diversity of the items the system made available.

The Aztec Empire subsequently expanded to include Oaxaca, parts of modern Guatemala, and regions bordering the Gulf of Mexico. By the time Moctezuma II (1502–1520 CE) assumed power, the empire was vast, with Tenochtitlán boasting a population of at least 200,000. Tenochtitlán was a remarkable city with extensive infrastructure, including large causeways, artificial agricultural islands called chinampas, and an advanced canal system for irrigation and transportation. The Templo Mayor, a grand dual stepped pyramid dedicated to the gods Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli, stood as a central religious and ceremonial hub. Although Aztec culture celebrated male virtues like bravery and strength, women, while largely confined to domestic roles, could also gain wealth and prominence as traders or leaders. Aztec state culture emphasized the complementarity of women and men, with men expected to fill roles outside the home like farming and fighting and women responsible for domestic chores like cooking and weaving.

Aztec society was made up of a number of social tiers. At the bottom was a large number of enslaved people and commoners with no land. Above these were the commoners with land. Before the imperial expansion, landed commoners had some limited political power. However, within the imperial system they were relegated to providing food and service for the military. Above them were the many specialized craftspeople, merchants, and scribes. And above all commoners were the nobles, who used conspicuous displays of wealth to elevate themselves. They served in the most important military positions, on the courts, and in the priesthood. The members of the Council of Four also came from the noble class. The council’s primary task was to select the Aztec emperor, or Huey Tlatoani, from the ranks of the nobility. The emperor occupied a position far above everyone else in Aztec society. His coronation included elaborate rituals, processions, speeches, and performances, all meant to imbue him with enormous power. Even high-ranking nobles were obliged to lie face down in his presence.

Life for the common person in Tenochtitlán was marked by hard work and dedication to the Aztec state. Most people lived in small, adobe homes with thatched roofs, surrounded by the bustling streets of the city. They spent their days working as farmers, artisans, or traders, with men often laboring in the chinampas (floating gardens) or markets, while women managed the household and raised children. Despite the social hierarchy, commoners had access to amenities like public baths, temples, and markets, and could participate in festivals and ceremonies. However, they were also required to provide tribute and labor to the nobles and the state and lived with the constant threat of war and human sacrifice. Amidst the grandeur and splendor of the Aztec capital, the common person’s life was one of simplicity, resilience, and devotion to the community.

The Aztecs imposed tribute payments on conquered territories, which flowed into the capital and benefited both the elite and commoners. Aztec society was stratified, with enslaved people and commoners at the lowest levels, and a noble class wielding substantial power. By the time Moctezuma II took the throne, the empire faced internal challenges and growing discontent over tribute demands and ritual sacrifices, setting the stage for the Spanish conquest that would reshape the region’s future.

The Inca Empire

At the same time the Aztec Empire was expanding across Mesoamerica, an equally remarkable civilization was emerging in the Andes region of South America: the Inca. This civilization, known to its people as Tawantinsuyu, had deep cultural and technological roots that extended back to earlier Andean cultures, including the Moche, Nazca, and Tiwanaku. The heart of the Inca Empire was the city of Cuzco, situated more than eleven thousand feet above sea level in the central Andes and northwest of Lake Titicaca. Long before Cuzco became the capital of a vast empire, it was a modest agricultural community where the ancestors of the Inca cultivated potatoes and maize and domesticated llamas and guanacos. These early practices laid the foundation for the agricultural expertise that would later sustain the Inca Empire.

The Inca Empire, known for its efficient and organized expansion, was divided into four regions called suyus, each governed by a relative of the emperor. These regions were further divided into provinces, often organized by local ethnic groups, and were overseen by Inca nobles. The empire’s agricultural productivity was impressive, with crops such as potatoes, coca, cotton, and maize stored in large warehouses, or qullqas, to feed armies and support the population during times of famine. Inca society was structured around mit’a, a labor system in which subjects contributed work to state projects, such as construction, road maintenance, or military service. While some household members participated in state labor, others managed domestic affairs, ensuring the continuity of daily life.

Religious beliefs were central to the Inca’s governance and unification efforts. The Inca used a complex ritual calendar, overseen by religious experts, to guide both political and military decisions. They worshipped a pantheon of deities, including the sky god Wiraqocha, the weather god Illapa, and the sun god Inti. The Inca rulers, who claimed descent from Inti, built grand temples in his honor and incorporated conquered peoples into the worship of Inti at the temple in Cuzco. This religious integration strengthened the bonds between the rulers and the diverse populations within the empire, fostering a sense of shared identity and purpose.

The Inca’s extensive road and bridge network was crucial in maintaining the cohesion of their vast empire, which spanned a diverse and challenging landscape of mountains, canyons, deserts, and coastal valleys. Unlike the Aztec Empire, which expanded across a relatively uniform terrain, the Inca Empire’s geography necessitated the construction of a sophisticated network of roads that may have reached 25,000 miles in length. These roads included straight paths, winding mountain trails, and bridges made of rope, stone, and wood. Inca armies, messengers, and goods moved efficiently across this network, connecting even the most remote provinces to the imperial center and ensuring the flow of resources to qullqas across the empire.

Learn More

In the fifteenth century, the Inca built a large palace complex high in the mountains above Cuzco that is now called Machu Picchu. You can tour the impressive ruins of Machu Picchu (https://openstax.org/l/ 77MachuPicchu) at this link.

Complex Societies in North America

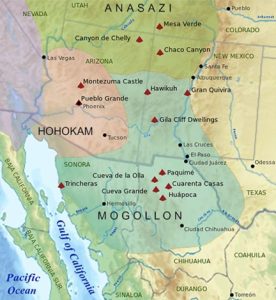

In the American Southwest, the establishment of permanent farming villages began well before 700 CE, with agricultural practices and village life emerging as early as 2000 BCE. By around 500 CE, these communities had become more widespread, featuring permanent homes and large storage pits for maize. The agricultural peoples of these villages can be broadly categorized into several cultural groups: the Mogollon in the south, the Hohokam in the west, and the Ancestral Pueblo (also called the Anasazi) in the north. Additionally, the Mimbres, Salado, and Sinagua cultures played significant roles in this region’s rich cultural mosaic.

The Mimbres, often considered part of the broader Mogollon culture, are particularly noted for their distinctive pottery, featuring intricate black-on-white designs depicting animals, humans, and geometric patterns. Their villages, centered in present-day southwestern New Mexico, were typically organized around plazas and included large communal structures known as pithouses. The Salado culture emerged around the 12th century CE, recognized for its unique blend of Hohokam, Ancestral Pueblo, and Mogollon influences. The Salado were known for their distinctive pottery, characterized by intricate polychrome designs, and their construction of multi-story pueblos in the Tonto Basin of present-day Arizona. The Sinagua people, who lived in what is now central Arizona, are known for their cliff dwellings, particularly at sites like Montezuma Castle and Walnut Canyon. Their culture, thriving between 500 CE and 1425 CE, shows influences from the Hohokam, Ancestral Pueblo, and Mogollon cultures, indicating extensive trade and interaction. The Sinagua were skilled farmers, cultivating crops in challenging environments and developing intricate irrigation systems.

Despite their differences, these groups shared similarities in their agricultural practices, village organization, and religious traditions, and they maintained contact with one another through trade and cultural exchanges. Early settlements often consisted of oval and circular pit houses, partly underground and constructed with wooden poles covered in dried mud. These homes were well-suited to the sun-drenched environment, providing cool refuge from the heat and preserving warmth during winter. Settlements varied in size, from a handful of homes to larger communities of up to sixty structures, with designs and complexity increasing over time. By 700 CE, large ceremonial meeting-house structures known as kivas had become common in the central and northern areas, serving as focal points for religious ceremonies and civic life. Over the next few centuries, these settlements evolved into larger complexes of multiroom structures built from dried adobe clay and stone. By 900 CE, permanent settlements were spread across the southwestern landscape, including modern-day New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado, Utah, Texas, and Chihuahua.

Some of the most impressive settlements include Pueblo Bonito in New Mexico, Cliff Palace in Colorado, Casa Grande in Arizona, and Casas Grandes in Chihuahua. Pueblo Bonito began expanding into a large masonry settlement around 800 CE, featuring pueblo-style rooms and kivas. The settlement reached its peak around 1000 CE, with a population of around one hundred people and served as a major ceremonial center. In addition to Pueblo Bonito, at least seventy other communities were scattered across the Chaco Canyon area, with a total population of up to 5,500 people. Connections between them are evident through shared pottery and architectural styles, as well as a network of roads that facilitated trade and communication.

However, a combination of factors, including prolonged drought, resource depletion, and social changes, led to the decline of many communities across the Southwest. By the late 13th century, several of these settlements, including Cliff Palace, had been abandoned as people moved to new areas in search of more sustainable resources. This marked the end of an era for these ancient communities, but their legacy endures in the remarkable cliff dwellings that remain—a testament to the ingenuity and resilience of the people who built them. The descendants of these ancient cultures, including the modern Pueblo peoples, continue to live in the region today, preserving and celebrating their rich heritage.

In the Eastern Woodlands, a new cultural phenomenon emerged around 700 CE, coinciding with the rise of settled agricultural communities in the Southwest. The Mississippian tradition, a mound-building culture, developed on the site of the earlier Adena and Hopewell traditions. This sophisticated culture constructed some of the largest and most impressive ceremonial mounds in the region. The adoption of maize agriculture from the south sparked the Mississippian tradition. Maize arrived in the Eastern Woodlands around 800 CE and was initially adopted by groups already familiar with farming edible plants like sunflowers and bottle gourds. By 1000 CE, maize cultivation had become widespread, even among groups without prior agricultural experience. Bean cultivation and the use of the bow and arrow for hunting small animals also spread throughout the region.

These changes led to a significant cultural shift in the Eastern Woodlands, marked by the emergence of large settled agricultural communities and the spread of common cultural, architectural, and technological practices. Settlements arose throughout the Mississippi River valley, from Georgia to Florida, with most being small chiefdoms centered around one or a few earthen mounds. Occasionally, smaller settlements coalesced into larger chiefdoms, and in a few cases, exceptionally large settlements with thousands of inhabitants developed.

The Mississippian site at Cahokia, near modern St. Louis, is one of the most elaborate and important researched thus far. Earlier settlements in the area date back to around 600 CE, but Cahokia began to emerge as a large urban center around 1050 CE, reaching its peak by 1250 CE before gradually declining. At its height, Cahokia and its surrounding settlements covered nearly four square miles, with a population of up to sixteen thousand people and over one hundred mounds. The central complex featured a network of large mounds, including a 100-foot-tall temple mound with a wooden structure and staircase, surrounded by a defensive wall with watchtowers.

Cahokia’s decline began around 1250 CE, and the settlement was eventually abandoned. However, this marked not the end of the Mississippian tradition, but rather a shift in its trajectory. Other sites, such as Moundville in Alabama and Etowah in Georgia, flourished in Cahokia’s wake. Yet, by approximately 1375 CE, these large chiefdoms also began to collapse. As the Mississippian tradition declined, the extensive trade networks that had connected the region began to disintegrate. The dispersal of people from the large settlements led to the emergence of new groups across the Eastern Woodlands. These groups retained many of the cultural traditions that had developed centuries earlier, but adapted to their new circumstances. The legacy of the Mississippian tradition continued to shape the region, even as its largest and most complex societies faded into memory.

Link to Learning

Learn more about the history and archaeological discoveries of Cahokia (https://openstax.org/l/77Cahokia) at the Cahokia Mounds Museum Society website. You can also explore an interactive map of Cahokia (https://openstax.org/l/77CahokiaMap) at this link.

In what is now the Northeast US and Canada, a complex civilization emerged between 600 CE and 1500 CE, marked by sophisticated agricultural societies, intricate trade networks, and impressive ceremonial centers. The earliest signs of this civilization appeared around 600 CE with the development of the Point Peninsula culture in present-day Ontario and the St. Lawrence River Valley. This culture, part of the broader Hopewell tradition, is characterized by the construction of elaborate burial mounds and the trade of copper and other valuable resources. As this culture evolved, it gave rise to more complex societies, including the Iroquoian-speaking peoples who would eventually form the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy. These societies were organized into matrilineal clans and featured elaborate ceremonial centers. For example, the Neutral Nation’s “Hill of the Dead” in present-day Brantford, Ontario, served as a significant ceremonial site. The trade networks established during this period extended from the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Coast, facilitating the exchange of goods and ideas.

By around 1200 CE, the influence of other complex cultures, such as those from the Mississippian tradition in the southeastern US, began to indirectly impact the Northeast. This period saw the rise of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians, who built large earthen mounds for ceremonial and burial purposes and engaged in extensive trade networks. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy, formed around the 12th to 15th centuries CE, united the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora nations under a powerful alliance. This confederacy played a significant role in shaping the region’s history, including its interactions with European colonizers.

The complex societies of the Northeast US and Canada were characterized by a rich cultural landscape, with diverse societies interacting, trading, and influencing one another. Many modern Native American communities trace their ancestry back to these ancient cultures. For example, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy is directly descended from these ancient societies, preserving many of their traditions and governance structures. The Anishinaabe peoples, including the Ojibwe, who have historically lived around the Great Lakes region, also trace their heritage to these early cultures. In Canada, the Huron-Wendat Nation, who are part of the broader Iroquoian-speaking group, continue to uphold traditions linked to their ancestors from this period. The legacy of these ancient cultures continues today, with these communities maintaining connections to their historical roots and cultural practices.

In Alaska and northern Canada, a complex civilization emerged between 600 CE and 1500 CE, characterized by sophisticated maritime societies, intricate trade networks, and impressive artistic traditions. The earliest signs of this civilization appeared around 600 CE with the rise of the Thule culture in the Arctic region. This culture is notable for its use of whalebone and driftwood in housing construction and the trade of whale products and other valuable resources. As the Thule culture developed, it gave rise to more complex societies, including the Inupiat and Yupik peoples in Alaska and their northern Canadian counterparts, who are direct descendants of the Thule. These societies were organized into kin-based groups and featured elaborate ceremonial traditions, such as the Bladder Festival. The trade networks established during this period extended from the Pacific Coast to the Arctic Ocean, facilitating the exchange of goods and ideas.

By 1200 CE, the influence of the Thule culture had spread throughout Alaska and northern Canada, leading to the emergence of even more complex societies, such as the Koniag (Aleut) and Chugach peoples in Alaska. These groups built large settlements and engaged in extensive trade networks, exchanging goods such as copper, obsidian, and sea otter pelts. The Inupiat and Yupik peoples developed a rich artistic tradition, including intricate carvings, masks, and textiles. The complex societies of Alaska and northern Canada were characterized by a diverse cultural landscape, with various groups interacting, trading, and influencing one another. The legacy of these ancient civilizations continues today, with many modern Native communities tracing their ancestry back to these cultures. Their cultural traditions remain vibrant and continue to be celebrated by their descendants.

In California, a complex civilization emerged between 600 CE and 1500 CE, marked by the development of sophisticated societies, intricate trade networks, and impressive artistic traditions. The earliest signs of this civilization appeared around 600 CE with the rise of cultures such as the Ohlone and Miwok in the San Francisco Bay Area and Sierra Nevada foothills. These cultures are noted for their acorn and seed-based economies and their trade of obsidian, shell, and other valuable resources. As these cultures developed, they gave rise to more complex societies, including the Chumash and Tongva (Gabrielino) peoples, who inhabited the coastal regions.

The Chumash culture, by 1200 CE, had developed a complex maritime society, known for their large plank canoes and extensive trade networks with other coastal societies. The Tongva people built elaborate ceremonial centers, including the significant site of Puvungna. Both the Ohlone and Miwok peoples developed rich artistic traditions, featuring intricate basketry and textiles. The complex societies of California were characterized by a vibrant cultural landscape, with diverse groups interacting, trading, and influencing one another.

Core Impact Skill — Perspective-Taking

The rise of complex Indigenous civilizations in what is now the U.S. and Canada offers a chance to rethink what we consider “civilization.” These societies developed sophisticated political systems, extensive trade networks, intricate artistic traditions, and profound spiritual ties to the land—yet they are often overlooked in standard narratives. From the Haudenosaunee Confederacy’s matrilineal governance to the Inupiat and Yupik reliance on sea-based economies, these cultures challenge modern assumptions about what power, development, and success look like. Taking their perspective seriously requires acknowledging ways of life centered not on conquest or domination, but on balance, kinship, and the sacred responsibilities of living well in place.

Engaging these histories invites us to reconsider how Indigenous communities understood leadership, economy, and the human relationship to land. Practicing perspective-taking means resisting the urge to measure these cultures by European standards and instead listening to their own values and voices—especially those that continue today in descendant communities.

-

How did Indigenous perspectives on land, trade, and governance differ from European ideas—and how did those views shape their societies?

-

What can we learn by seeing civilization not just in terms of monuments or empires, but through the lens of cultural sustainability and reciprocity?

Studying the past with perspective-taking in mind helps us expand our understanding of what counts as “history”—and prepares us to better respect diverse worldviews in the present.

The legacy of these ancient cultures continues today in modern Native communities. For example, the Ohlone descendants, such as the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, continue to maintain their cultural heritage and traditions in the San Francisco Bay Area. The Chumash people, represented by organizations such as the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians, also continue to uphold their rich cultural practices and historical legacy. These communities remain active in preserving their cultural traditions and contributing to the ongoing cultural landscape of California.