28 The Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula, a vast and diverse region in Southwest Asia, has a rich history spanning thousands of years. Bounded by the Red Sea to the west, the Persian Gulf to the north, and the Indian Ocean to the south, this region has been home to numerous cultures and civilizations. The Sabaeans, who established a powerful kingdom in modern-day Yemen around 1500 BCE, were among the earliest known inhabitants. Renowned for their advanced irrigation systems, the Sabaeans transformed the arid landscape into productive farmland, fostering a thriving economy. Their distinctive writing system and architectural achievements, including elaborate temples and monuments, further attest to their sophistication.

In the centuries leading up to the early medieval period, the Arabian Peninsula was characterized by a complex network of tribes and trading cities. Mecca, located in the Hejaz region, emerged as a major commercial hub, attracting visitors from across the ancient world. The Meccans’ prowess in trade and commerce established their city as a focal point of economic activity. A sophisticated system of governance, including a council of elders and a network of alliances with neighboring tribes, further solidified Mecca’s position. However, internal challenges related to governance and social issues threatened the city’s stability.

By the 6th century CE, the Arabian Peninsula was a region of significant geopolitical dynamics. The Sassanian Empire and the Byzantine Empire competed for control of key trade routes, while local tribes engaged in ongoing struggles for power and resources. This period of considerable change and adaptation set the stage for subsequent transformations in the region’s social and political landscape. The complex interplay of internal and external factors created a volatile environment, ripe for the emergence of new forces that would shape the region’s future.

The Rise of Islam

As the Byzantine-Sasanian conflict raged in the early seventh century, western Arabia emerged as the cradle of a new monotheistic faith – Islam. Meaning “submission to the one God,” Islam shares commonalities with Judaism and Christianity while incorporating unique Arabian features. While influenced by the two monotheistic traditions of Judaism and Christianity that preceded it, Islam retains distinctive Arab characteristics. The faith has deep roots in the Arabian Peninsula, particularly in western Arabia, where its holiest sites are located and where its founder spent most of his life. Arabic, the indigenous language of the region, is central to Islam’s sacred texts and cultural practices, including the use of poetry to preserve history. The tribal structure of Arabian society also influenced the early development of Islam, with conversion often involving integration into an Arab tribe. This process meant adopting Arabian cultural norms and practices, though it did not require a specific ethnicity or bloodline. For early believers in Muhammad’s messge, it appeared that God had chosen the western Arabian peoples and their traditions for a special purpose, making these cultural aspects significant for those considered among the “chosen” people. The leadership and message of Muhammad, the final prophet from the Hijaz region, were pivotal in shaping the faith and its development.

Muhammad was a prominent merchant from the Quraysh tribe in the Hijaz region. Born in Mecca, he spent his early life engaged in trade along the north-south routes passing through the city. The Quraysh dominated leadership and trade in the region due to their role as protectors of the sacred Kaaba, a revered sanctuary that had come to be a central site for various religious practices. In 610, according to Islamic tradition, Muhammad received revelations from God through the angel Gabriel while contemplating in a cave outside Mecca. He was told to recite the first verses of the Quran, the Muslim holy book. Despite the risks, Muhammad abandoned his comfortable life as a merchant to become a preacher, believing it was his duty to save his family and kin from a coming day of judgment.

The first person to convert to Islam was Muhammad’s wife, Khadija, a successful merchant who had lifted Muhammad’s standing in the community. She provided critical support, believing in him and accepting the revelations as true. Many of Muhammad’s confidants and family members soon followed, but his early career as a prophet was marked by challenge and resistance. The support of his family, especially his wives, was crucial to his success. Tradition suggests that Khadija convinced Muhammad to trust his new calling when he doubted his sanity. In 622, Muhammad’s community fled persecution in Mecca and emigrated to Medina, a watershed moment that marked the beginning of Islam as a larger, united community. This hijra, meaning “emigration,” was a watershed moment for Muhammad’s early community. At a low ebb and without any certainty of survival, Islam now changed from a small religion mostly confined to Mecca to a larger community united by Muhammad that solidified its place in world history. The hijra holds such importance in the history of Islam that the Islamic lunar calendar counts 622 CE as its first year. (Dates in the Muslim calendar, used by many around the world today, are often labeled in English with AH, for “After the Hijra.”)

Link to Learning

Learn more about Islam and the Muslim by reading Dr. Mack’s chapter on Islam in his book, Religions of the World: Introduction.

Muhammad’s message, leadership, and the early Muslim community were influenced by various factors, including the social, economic, and political context of 7th-century Arabia, interactions with other religious groups, and the traditions of Arabian culture. His personal experiences, including his encounters with Christian and Jewish scholars, also played a role in shaping his message. Additionally, Muhammad’s leadership was marked by his role as a mediator in tribal disputes, which helped him address the changing needs of his community. Support from other communities was significant for Muhammad and his followers. For instance, before the migration from Mecca to Medina, some of Muhammad’s followers (known as Muslims) sought refuge in the Christian Kingdom of Aksum (modern-day Ethiopia), where the Negus, the leader of Aksum, offered them protection and allowed them to practice their faith freely. This support was crucial for the survival of the early Muslim community and exposed them to different cultural and religious contexts, which influenced their understanding of Islam. The support from Aksum also demonstrated that Muhammad’s message resonated beyond the Arabian Peninsula, aiding its expansion.

In Medina, Muhammad established an alliance with various groups to ensure mutual defense. As an arbiter and later as the city’s leader, Muhammad helped resolve disputes and set up a framework for governance through the Constitution of Medina. This document formalized the community’s mutual responsibilities and defense commitments, setting a precedent for Muslim governance. The Constitution of Medina also promoted religious freedom, allowing Muslims to practice their faith openly. Medina became a center of Muslim growth and development, attracting new followers and shaping the future trajectory of the Muslim community.

Muhammad’s impartial treatment of his new community, the ummah, was crucial to his ultimate triumph. During the last decade of his life, Muhammad focused on building this community in Medina, while engaging in intense conflicts with his former allies in Mecca. The battles between the two sides were brutal, and internal tensions arose within Medina as Muhammad’s followers gained prominence, overshadowing other Arab groups. The fact that many individuals on both sides were related by blood added complexity to the situation, despite their differing religious beliefs. Nevertheless, Muhammad’s community continued to expand. When Mecca’s population converted to Islam, Muhammad and his followers returned to Mecca. There, he entered the sacred Kaaba and destroyed with images representing the various religions which had been centered there. From a Muslim perspective, this act purified the sacred Kaaba, restoring its dedication to the worship of the one true God. This act also verified that Muhammad succeeded in uniting the majority of Arab tribes of western Arabia under his leadership. He spent his final years working to expand his community and spreading the message of Islam, until his death from natural causes in the year 632.

The Newly Formed Caliphate

Following Muhammad’s death in 632 CE, the Muslim community faced urgent questions about leadership and disagreements arose. In Arab society, leadership wasn’t automatically passed down to the leader’s heir, so two prominent figures emerged as potential successors: Ali ibn Abi Talib, Muhammad’s son-in-law, and Abu Bakr, a respected elder and close friend of Muhammad. Although Ali claimed to have been chosen by Muhammad as his heir, Abu Bakr was ultimately selected as the first caliph through a process of tribal leaders’ acclamation. This decision had long-term implications for the unity of the Muslim community.

The community also grappled with questions of identity and standing. Some members had been early converts, while others had joined later or provided shelter to the community in Medina. The selection of Abu Bakr as caliph addressed the immediate need for leadership, but it also marked a significant change, as he didn’t claim prophetic powers like Muhammad.

Tensions arose over leadership, inheritance, and the future of the alliance. Some Arab tribes abandoned the community, leading to the Ridda Wars, a conflict aimed at forcing them to uphold their agreements. The conflict also contributed to the expansion of the Arab polity, incorporating new tribes and territories. By 633, the Arabian Peninsula had largely coalesced into a unified political entity, shaped by the convergence of social, tribal, and cultural dynamics, with Islam serving as an important, though not exclusive, force in fostering both political cohesion and spiritual identity.

Abu Bakr did not live long after Muhammad, and the expansion of the new polity continued beyond his leadership and the unification of the Arab tribes. The emerging state’s efforts to both protect itself and assert its presence beyond the Arabian Peninsula were evident early on, as Arab armies began looking northward toward the established empires of Sasanian Persia and Byzantium. These regions, known for their wealth and abundant resources, attracted attention for their strategic and economic potential. However, other motivations played a role as well. Many of the Arab forces, having succeeded in unifying Arabia, viewed their victories as signs of divine favor, reinforcing their belief in a broader mission to extend their influence.

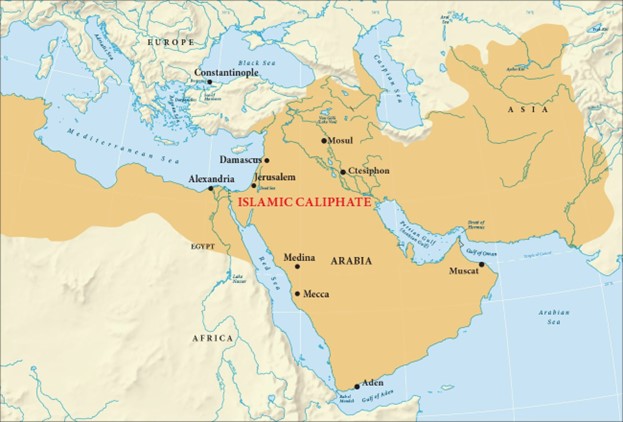

Between 634 and the early 700s, Arab forces, united by tribal alliances and the shared faith of Islam, expanded extensively across the Mediterranean and central Asia. Their reach extended from the western shores of Spain and Portugal to the eastern banks of the Indus River valley. As their empire grew, these forces shifted from a loose group of tribes to a well-organized imperial system, known as the Caliphate. The first four caliphs—Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali, Muhammad’s son-in-law—led this expansion from 632 to 661. During this time, they brought much of Byzantine and Persian territory under their control and spread Islam throughout a predominantly Christian Middle East. This transformation allowed the Caliphate to become the largest empire in history, surpassing even the achievements of Alexander the Great, the Romans, and the Han Chinese.

The early years of expansion saw several significant battles, including Yarmuk and Qadisiyya. However, most territories actually came under the political control of the Caliphate through peaceful agreements. Cities and regions surrendered on terms that protected their residents, allowed them to keep many of their belongings, and guaranteed their right to practice their religion. This approach made sense for non-Muslim populations, especially since the Muslims initially adopted a policy of noninterference in the religious practices of their subjects. For many, life under Islamic rule was an improvement. Non-Arabs and non-Muslims had incentives to contribute to the Muslim effort, as they could receive a share of the spoils of war and gain standing in the new society. These benefits likely motivated many to join the conquests. As long as they paid taxes to their new Muslim government, conquered peoples could live in the Islamic state and practice their religion with relative freedom. The Muslims developed a legal classification for Jews, Christians, and Zoroastrians, calling them “ahl al-kitab” or “People of the Book.” This recognized them as monotheists who had received divine revelations in the past and were worthy of protection by the Islamic state, provided they submitted to Muslim rule and paid taxes.

The Rashidun caliphs played a crucial role in shaping the early identity of Islam and interpreting its teachings. They were instrumental in overseeing the compilation of the Quran and developing Islamic jurisprudence. When the Quran did not address specific issues, they relied on the hadith—the sayings and actions of Muhammad and his closest companions—for additional guidance.

Key figures like Aisha, Muhammad’s youngest wife, were essential in transmitting and interpreting the hadith. However, the Rashidun period was marked by significant controversy. The fourth caliph, Ali ibn Abi Talib, faced considerable opposition, leading to the First Fitna (656-661 CE), the first major civil conflict within the Muslim community. This conflict was sparked by the assassination of the third caliph, Uthman ibn Affan, and the ensuing struggle over who should be held accountable for his death, which further polarized the community. During the First Fitna, early supporters of Muhammad, including Aisha, engaged in battles against each other. The conflict deepened with Ali’s eventual assassination in 661 CE, leading to the rise of the Umayyad dynasty (661 to 750 CE) under Mu‘awiya ibn Abi Sufyan. The Umayyads marked a significant shift toward hereditary rule.

The Umayyads faced internal conflicts within the ummah, particularly regarding Arab ethnicity. As their empire expanded, they relied on non-Muslim, non-Arab bureaucrats to govern. However, by the eighth century, these officials were being replaced by Arabs, leading to frustration among new converts and non-Muslims. The Umayyads saw Islam as an Arab religion, believing God sent the Arab prophet Muhammad to spread his message in Arabic. Conversion to Islam meant adopting Arab culture, requiring non-Arabs to be adopted by an Arab tribe as a protected member, known as a mawali (a client or affiliate of an Arab tribe, granted protection and acceptance but not equal status). This process discouraged conversion. As Arab-Muslims settled in conquered regions, intermarrying with locals, the focus on “Arabness” faced scrutiny. The Umayyads’ treatment of mawali as second-class citizens ultimately led to their downfall, paving the way for a more inclusive universalistic view of Islam.

The Abbasid Caliphate

The final decades of Umayyad rule were marked by internal power struggles and factionalism. Arab tribes competed for influence, while non-Arab Muslims, particularly in the eastern province of Khurasan, grew increasingly frustrated with their marginalization. In Khurasan, Arab-Muslim settlers had intermarried with indigenous Persians, producing a mixed-ethnicity population that felt disenfranchised by the mid-8th century. This led to a surge in revolutionary activity, as individuals sought a more inclusive Islamic community where all ethnicities could enjoy equal benefits.

A group of reformers, dissatisfied with Umayyad rule, began secretly meeting to envision a more equitable society. They advocated for the rights of marginalized groups, including supporters of the fourth caliph, Ali, and his family. In 749, after years of growing discontent, this group rebelled against the Umayyads, overthrowing them within a year and establishing the new Abbasid dynasty (750 to 1258 CE).

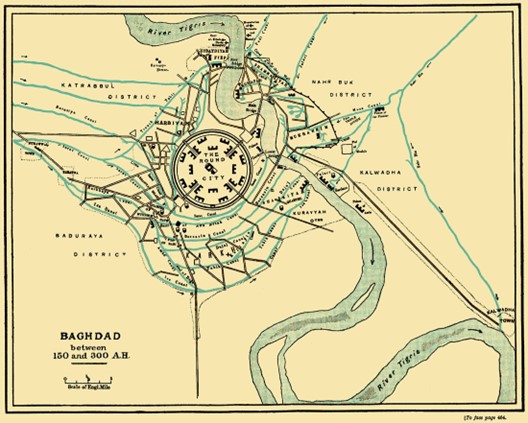

Upon taking power, the Abbasids shifted the focus of their Caliphate eastward by founding their capital, Baghdad, in central Iraq. This decision marked a significant turning point in the region’s politics and economics. The inhabitants of the former Persian Empire, who had played a crucial role in the Abbasids’ rise to power, became a vital power base for the dynasty as it expanded. As a result, Persian language, culture, and traditions began to exert a profound influence on early Islamic society, particularly at the court in Baghdad. Meanwhile, Baghdad’s growing prominence led to a shift in the center of trade, surpassing traditional Mediterranean hubs like Alexandria, Antioch, Constantinople, Damascus, and Jerusalem. The city’s strategic location along the Silk Roads, which connected to the Indian Ocean world and a rapidly expanding China, further solidified its position as a major commercial hub, drawing trade and cultural exchange further east. Baghdad, a planned city, was designed to harness the vast wealth and talent accumulated during the Umayyad era. Situated on the fertile banks of the Tigris River, Baghdad flourished as a center of trade and culture, expanding into the surrounding farmland and becoming a testament to the Abbasid state’s growing prosperity and influence.

Early Abbasid society was a remarkable achievement, driven by Baghdad’s growth, courtly culture, and a diverse population. The Abbasids strongly supported learning, initiating the Abbasid Translation Movement to translate ancient Greek and Persian works into Arabic. This movement aimed to preserve knowledge, attract top scholars, and create a culture of learning among the elite.

New technologies, like Chinese papermaking, made books more affordable, sparking a surge in learning. Islamic schools (madrasas) were founded, providing exceptional educational opportunities. The translation movement achieved significant milestones, preserving essential texts, including works by Aristotle, Galen, and Ptolemy, which were studied extensively in the Abbasid world.

In addition to scientific texts, the Abbasids translated Persian works on governance, etiquette, history, and economics to train bureaucrats, known as “secretaries,” who managed the empire. The Translation Movement wasn’t just about preserving ancient knowledge—it involved updating and correcting old manuscripts, especially scientific ones.

Baghdad became a center of wisdom, valuing continuous learning and scholarship. Although many contributors remain anonymous, their efforts allowed the Abbasids to apply contemporary knowledge to traditional ideas. This era was defined by a spirit of openness to both old and new ideas, drawing from the Mediterranean, Central Asia, and the Indian Ocean, making the Abbasid empire a hub of intellectual growth and innovation.

Religious tolerance was a defining feature of life during the Abbasid period. Muslims, Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians lived and worked together in relative harmony, though not on equal footing. While Islam was the dominant religion, non-Muslims, known as dhimmis, were allowed to practice their faiths freely as long as they paid the jizya, a special tax. This tax granted them protection and the right to worship but also reinforced their status as second-class citizens. Despite these limitations, ordinary people could go about their daily lives without fear of persecution. Many took advantage of opportunities to learn from and engage with people of other faiths. In fact, Christians and Jews held important positions in government and commerce, and Muslim scholars often sought the expertise of non-Muslim scholars, particularly in fields like medicine and astronomy, contributing to the era’s intellectual achievements.

Family and gender roles in the Abbasid period were shaped by the social customs of the diverse religious communities. Across Muslim, Christian, and Jewish households, families tended to live in extended family structures, with multiple generations under one roof. In these societies, women typically managed the household and raised children, while men worked outside the home and provided for their families. The restrictions on women’s public roles were similar across these faiths, with Muslim, Christian, and Jewish women facing social norms that limited their participation in public life. However, women from wealthy families, regardless of their religious background, often had more opportunities for education and greater social freedom. Some even became prominent scholars or patrons of the arts. Despite the limitations imposed by gender roles, both men and women found ways to express agency and individuality through their work, relationships, and religious practices.

A Growing Divide in the Muslim Community

The early Abbasid period brought initial stability to the Islamic world, but it was short-lived. As the Islamic community expanded, doctrinal differences and debates over leadership led to the formation of distinct sects. The two major branches, Sunni and Shia, emerged from this growing divide.

Sunni Muslims follow the customs of the Prophet Muhammad and recognize Abu Bakr, the Prophet’s father-in-law, as the rightful successor after Muhammad’s death. They adhere to a standardized interpretation of the Quran and hadith. Today, Sunni Muslims form the largest group of Muslims worldwide. Shia Muslims, by contrast, believe that Ali, the Prophet’s son-in-law, was the rightful leader after Muhammad’s death. They revere the Prophet’s family, particularly Ali’s descendants, and believe they possess divine knowledge and authority.

In the medieval period, the Sunni-Shia divide was not as rigid as it is today. Sunnis respected the Prophet’s family but did not view Ali’s bloodline as having an exclusive right to rule. However, as political rivalry grew, Shia Muslims increasingly emphasized the divine authority of imams from Ali’s lineage.

Alongside these developments, Sufism emerged as a mystical movement within Islam. Early Sufis sought a deeper connection with God, emphasizing inward piety, devotion, and spiritual purification. They often pursued ascetic lifestyles, renouncing material wealth to focus on their relationship with the divine.

Sufism emerged partly as a reaction to the growing formalization of religious practice and the increasing influence of the ulama. While the ulama focused on Islamic law, Sufis sought direct experiences of God through meditation, prayer, and chanting. Early Sufi leaders laid the groundwork for the movement’s development by emphasizing love of God and the purification of the soul.

By the 9th century, Sufism began to gain a broader following, blending both Sunni and Shia elements while maintaining a distinct spiritual focus. Though Sufism often operated on the margins of formal religious institutions, it would later become a significant force within the Islamic world, contributing to its rich intellectual and spiritual traditions.

Core Impact Skill — Perspective-Taking

The Abbasid era highlights the diversity of thought and practice within Islam as Sunni, Shia, and Sufi traditions developed distinct views on leadership, authority, and spiritual life. These differences emerged from complex historical, political, and theological contexts, shaping how each community understood its role within the broader Islamic world. Practicing perspective-taking means stepping into these worldviews—examining how each tradition justified its beliefs, related to the others, and interpreted shared history. This is especially important for understanding Muslim history, where people today often assume all Muslims think and practice alike. Recognizing this diversity allows us to move beyond generalizations and appreciate the many ways Islamic identity has been expressed over time.

-

Based on historical evidence, how might Sunni, Shia, and Sufi communities each have interpreted key events of the Abbasid period?

-

What does this example reveal about the importance of listening to multiple perspectives when interpreting events in both the past and the present?