3 The Neolithic Revolution: A Transformation in Human History

The shift from hunting and gathering to agriculture, known as the Neolithic Revolution, was a pivotal transformation in human history. This revolution occurred independently in various regions, including the Near East, China, sub-Saharan Africa, Mesoamerica, and South America, around 12,000 years ago. Each region domesticated different plants, such as wheat, barley, squash, maize, millet, and rice, which grew naturally in those areas. The reasons for this shift are not fully understood, but climate change and the end of the last ice age may have played a role. As humans attempted to help edible plants grow, they began to notice and intervene in their growth, leading to domestication.

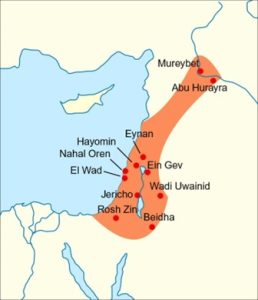

The Fertile Crescent, a region including Mesopotamia, southern Turkey, and Israel, was one of the first areas to adopt agriculture. Wheat, barley, peas, lentils, and other crops were domesticated here. Agriculture also developed in other regions, including Asia, Africa, and the Americas.

The rise of agriculture led to significant changes, including:

- Domestication of plants: Humans selected and transformed plants for edible properties, leading to gradual changes in the plants themselves.

- Domestication of animals: Animals were selected for beneficial characteristics, such as docility and strength, leading to the domestication of species like sheep, goats, chickens, horses, and llamas.

- Expansion of agriculture: Techniques spread to new areas, leading to the growth of settled agriculture and the development of human civilization as we know it.

This revolution marked a significant turning point in human history, enabling the growth of larger populations, the development of complex societies, and ultimately, the rise of modern civilization.

Before agriculture, hunter-gatherers spent around 20 hours per week acquiring food, allowing for ample leisure time and a relatively healthy lifestyle. In contrast, agricultural societies spent 30 or more hours engaged in farming, leading to a decrease in leisure time. However, agriculture also allowed for settled communities, enabling the development of more complex social structures and cultural practices. Additionally, while agricultural communities were more vulnerable to epidemic diseases, they also had access to more consistent food sources, reducing the risk of famine.

Prior to agriculture, hunter-gatherers enjoyed a diverse diet consisting of a wide variety of plants and animals. In contrast, the diet of farmers was less diverse, consisting mainly of staple crops. However, agriculture also allowed for the domestication of animals, providing a reliable source of protein and dairy products. Additionally, settled agriculture enabled the development of food storage techniques, reducing the risk of food scarcity.

Before agriculture, hunter-gatherer societies were relatively egalitarian, with shared resources and responsibilities. In contrast, agriculture allowed for larger populations and the emergence of labor specialization, leading to social divisions. However, agriculture also enabled the development of complex societies with specialized labor, allowing for the emergence of artisans, traders, and other professions. Additionally, settled agriculture enabled the development of more complex systems of governance and social organization.

In pre-agricultural societies, men and women had relatively equal roles and responsibilities. In contrast, the shift to agriculture led to a division of labor, with men taking on more prominent roles in farming and women being relegated to domestic tasks. However, agriculture also enabled the development of more complex social structures, allowing for the emergence of female leaders and specialized female labor. Additionally, settled agriculture enabled the development of more stable family structures, allowing for greater investment in childrearing and education.

Before agriculture, religious practices were often centered around animism and shamanism. In contrast, the shift to agriculture led to the emergence of highly defined priestly classes, who derived their authority from their ability to interpret the intentions of the supernatural world. However, agriculture also enabled the development of more complex and nuanced religious systems, allowing for the emergence of new spiritual practices and beliefs. Additionally, settled agriculture enabled the development of more permanent religious structures, such as temples and shrines, providing a sense of community and shared spiritual practice.

Core Impact Skill: Perspective-Taking

As you reflect on the shift from hunting and gathering to agriculture, take a moment to put yourself in the shoes of someone living through this transformation. What would it feel like to give up a mobile lifestyle with plenty of leisure time for the stability—but hard labor—of farming? How might your daily life change if you suddenly had access to stored food but also faced new risks like disease or crop failure?

Perspective taking helps you explore these questions by encouraging you to see the world through different eyes. Think about how this shift affected different groups:

-

How did life change for women compared to men?

-

What might a young child experience growing up in a farming village versus a foraging group?

-

How would a spiritual leader’s role evolve in a settled community with temples and priestly classes?

By considering these diverse viewpoints, you’re not just learning about history—you’re learning to understand people across time and culture. That’s the heart of perspective taking.

Neolithic Settlements and Communities

Around 9,000 years ago, Neolithic peoples began establishing large and complex permanent settlements in various regions, including Europe, the Near East, China, Pakistan, and beyond. These settlements were characterized by the practice of agriculture, the use of pottery, and the development of complex social structures. The people of these settlements combined farming with hunting and gathering, and traded goods with neighboring communities.

Çatalhöyük: A Thriving Neolithic Settlement: Çatalhöyük, located in southeastern Turkey, is one of the largest and most well-known Neolithic settlements. Occupied for over 1,200 years, this settlement covered more than 30 acres and may have been home to as many as 6,000 people. The residents of Çatalhöyük were farmers, hunters, and skilled craftspeople who lived in mud-brick houses with no roads or passages between them. They entered their homes from the roof, which provided protection from the outside world. The settlement was a center of trade, with goods such as obsidian, clay vessels, and woven items being exchanged for other valuable commodities.

Jericho and Other Neolithic Settlements: Jericho, located in the Jordan River valley, was occupied as early as 8,300 BCE. This settlement was protected by a large ditch and a thick stone wall, and featured a large stone tower. Similar settlements were found at Ain Ghazal and Nahal Hemar. In the Euphrates River valley, the settlement of Abu Hureyra was established. These settlements were part of the Natufian culture, which predates agriculture. The Natufian people settled in areas rich in wild edible plants and animals, and later adopted agriculture and built Neolithic settlements.

Neolithic Settlements in South Asia: In South Asia, the Neolithic settlement of Mehrgarh in modern Pakistan was established around 7,000 BCE. The people of Mehrgarh farmed barley, raised goats and sheep, and later domesticated cotton. They were skilled artisans who used materials from great distances away, indicating long-distance trade. The settlement was divided into four parts, with homes made of dried mud bricks and rectangular in shape.

Neolithic Settlements in China: In China, the earliest Neolithic settlements were located along the Yellow and Yangtze rivers. The people cultivated millet, rice, and domesticated pigs and dogs. They also made cord from hemp and pottery from clay. Two of the early sites discovered in China are Pengtoushan and Bashidang, both located in the Yangtze River valley. These settlements may have been established as early as 7,500 BCE and preserve evidence of some of the earliest cultivation of wild rice.

Global Neolithic Settlements: Similar Neolithic settlements have been discovered in various regions, including the Americas, South America, New Guinea, Europe, and central Africa. These settlements share characteristics such as permanent settlement, agriculture, pottery, and complex social structures. The earliest known agricultural settlements in the Americas have been found in northeastern Mexico, where people were cultivating plants like pepper and squash as early as 6,500 BCE. In the Andes Mountains region of South America, Neolithic settlements growing potatoes and manioc began to emerge as early as 3,000 BCE.