29 The Ottoman Empire

The Abbasid dynasty’s decline began in the 10th century, triggered by internal power struggles, regional rivalries, and external threats. As the caliphate fragmented, provincial governors and regional dynasties asserted their independence, reducing the Abbasid caliphs to figureheads. The Buyids, a Shia Persian dynasty, seized control of Baghdad in 945, stripping the caliphs of political power.

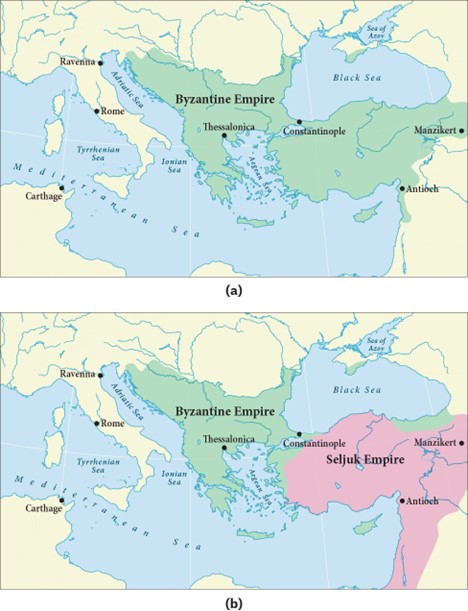

The Seljuk Turks, Sunni Muslims from Central Asia, rose to prominence and briefly restored stability to the Abbasid realm. In 1055, they defeated the Buyids and entered Baghdad, positioning themselves as defenders of the Islamic faith. The Seljuks established their own empire, dominating Persia, Mesopotamia, and eastern Anatolia. They notably defeated the Byzantine Empire at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, which paved the way for their control of eastern Anatolia.

In 1077, the Seljuks established the Sultanate of Rum in Anatolia, a centralized state rather than a confederation of tribes. The sultanate’s ruler was a military leader, with provinces governed by military commanders. The Seljuks built mosques, madrasas, and caravansaries, attracting merchants, artisans, and scholars. As Byzantine control over the region wanted, many inhabitants of the region gradually converted to Islam, influenced by various social and political factors.

As the Seljuk dynasty’s power waned, the Sultanate of Rum emerged as the last stronghold of Seljuk control in Anatolia. However, this region too faced ongoing political and military upheaval. The Mongols’ invasion of eastern Anatolia in 1243 marked a turning point, as they defeated the Seljuks at the Battle of Köse Dağ (in northeastern modern-day Turkey). This led to the fragmentation of the Sultanate of Rum into numerous small, independent states known as beyliks. In the 14th century, one of these beyliks began to gain prominence as Seljuk influence declined in the aftermath of the Mongol invasions. This rising power was led by a leader named Osman, whose followers became known as the “Osmanli” or “Ottomans.”

The Ottoman Empire

The Ottomans were a Turkish-speaking people who initially inhabited the northwestern regions of Anatolia. Their early way of life was pastoralist, but as they expanded, they increasingly adopted settled agricultural practices. They saw themselves as ghazis, warriors who fought to expand and protect the influence of Islam and assert their own political and territorial ambitions. This self-image was shaped by their historical context, geographical location, and cultural exchanges with other Muslim groups, such as the Seljuks. The ghazi identity became a defining feature of Ottoman culture, influencing their political, social, and religious institutions, and driving their expansion into the Balkans, Anatolia, and beyond.

The Ottomans rose to power during a time of significant upheaval in the region. The Byzantine Empire, which had long dominated the area, was weakening. The Ottomans capitalized on this power vacuum, conquering key cities in Anatolia and establishing their capital at Bursa (located in modern-day Turkey, about 100 miles southeast of Istanbul). As they expanded their territory, they built mosques and madrasas, transforming Bursa into a major center of Islamic learning and culture. This marked the beginning of Ottoman dominance in the region.

The Ottoman Empire was founded by Osman I (1299–1326), a Turkish tribal leader who laid the groundwork for Ottoman expansion. His son Orhan I (1326–1362) built upon this foundation, expanding Ottoman territory and establishing a strategic base on the Gallipoli Peninsula (a coastal region in northwestern Anatolia, Turkey, bordering the Dardanelles Strait). This location allowed the Ottomans to control sea traffic between the Mediterranean and Black Sea and interfere with ships bound for Constantinople.

Orhan’s son Murad I (r. 1362–1389) established a new capital at Edirne (a city in northwestern Turkey, near the border with Greece and Bulgaria) in 1361 and invited Turks from Anatolia. He sought to expand Ottoman territory further, defeating the Serbian army at the Battle of Kosovo in 1389 and making Serbia a vassal state. Although both Murad and the Serbian ruler Prince Lazar died in the battle, the Ottomans emerged victorious.

Following the reign of Murad I (1362–1389), the Ottoman Empire aimed to establish itself as the dominant power in the Middle East. The Byzantine Empire, with its strategic capital Constantinople, served as a significant counterweight to Ottoman ambitions. Bayezid I (1389–1402) attempted to capture Constantinople, but his efforts were thwarted by the Mongol conqueror Timur (Tamerlane) at the Battle of Ankara in 1402. Following Bayezid’s defeat, the Ottomans faced a period of internal strife known as the Ottoman Interregnum, which lasted until 1413.

Under the leadership of Murad II (1421–1451), the Ottomans overcame these challenges and continued their expansion. Murad II consolidated Ottoman control and extended the empire’s influence into much of the Balkans, Anatolia, and parts of the Middle East. This period set the stage for his son, Mehmed II, to conquer Constantinople in 1453, which solidified Ottoman dominance in the region.

Mehmed the Conqueror

Mehmed II (1432-1481), also known as Mehmed the Conqueror, aimed to eliminate the Byzantine Empire, which was a major obstacle to Ottoman dominance. In 1453, he assembled a formidable force that included Muslim and Christian vassals, elite soldiers, and a powerful navy. He also employed European gunsmiths to create advanced cannons that played a crucial role in breaching Constantinople’s defenses after a 57-day siege. On May 29, 1453, Ottoman forces captured the city, marking the end of the Byzantine Empire.

Beyond Constantinople, Mehmed II extended Ottoman control over various regions. He annexed Turkish states, conquered Trebizond (the last Byzantine stronghold), and gradually gained control of southern Greece, Bosnia, and Albania. He also secured key trade centers, such as Kaffa. Despite his reputation as a conqueror, Mehmed was also a builder. He transformed Constantinople into the Ottoman capital, later known as Istanbul, and undertook an ambitious rebuilding campaign. He constructed significant structures including the Topkapi Palace, the Hagia Sophia mosque, city walls, a weapons foundry, and a hospital. The Fatih Mosque and numerous madrasas were built under his reign, solidifying Istanbul as a center of Islamic learning and culture.

Link to Learning

Visit this UNESCO site to learn more about Istanbul (https://openstax.org/l/77UNESCOIstan) and to view pictures of its famous historic sites.

Mehmed II was a knowledge-seeking leader who spoke multiple languages and amassed a vast library of works in various languages. He invited scholars, engaged in debates, and collected Greek antiquities. He brought Greek scholars and Italian artists to Istanbul. As he expanded his empire, Mehmed also brought artisans and prisoners of war to aid in rebuilding the city. He allowed Christians and Jews to practice their religions freely and established the Ottoman millet system, which granted religious communities a degree of autonomy and self-governance. In addition to these accomplishments, Mehmed exerted control over Islamic clergy by making madrasa teachers state employees and issuing laws (kanun) to centralize his authority.

Core Impact Skill — Persuasion

Mehmed II’s reign demonstrates how persuasion can reinforce both political authority and cultural prestige. Known as “Mehmed the Conqueror” for capturing Constantinople in 1453, he skillfully combined military triumph with a deliberate effort to present the Ottoman Empire as a center of learning, art, and religious tolerance. Fluent in multiple languages and an avid collector of books, Greek antiquities, and artistic works, Mehmed invited scholars from across the Mediterranean and beyond to his court, hosting debates and commissioning architectural projects that projected Ottoman sophistication. By welcoming Greek scholars and Italian artists, he aligned his rule with both Islamic and classical traditions, appealing to diverse audiences at home and abroad.

We learn about persuasion by studying how Mehmed used these cultural initiatives alongside strategic governance reforms. By instituting the millet system, he persuaded Christian and Jewish subjects that their religious and communal life would be protected under Ottoman rule, fostering loyalty in a diverse empire. At the same time, he centralized power by making madrasa teachers state employees and issuing laws (kanun) that asserted his authority over the Islamic clergy. Mehmed’s approach illustrates how a ruler can use persuasion not only through speeches, but through policy, cultural patronage, and symbolic acts that embody stability, inclusivity, and power.

-

How did Mehmed II’s patronage of learning and the arts serve as a persuasive tool for uniting his empire and enhancing its reputation abroad?

-

What does the millet system reveal about the role of persuasion in managing religious diversity within a multiethnic empire?

By examining Mehmed’s reign, we see how persuasion can operate through the careful blending of military achievement, cultural diplomacy, and legal reform to shape both the image and the reality of imperial rule.

With the fall of the Byzantine Empire and the decline of Timurid authority, the Ottomans emerged as a dominant force in the 15th century. They controlled important trade routes and ports, and by the late 15th century, Ottoman ships were trading with India. Luxury goods such as Chinese silks and porcelains became prominent in Istanbul’s elite circles. The Ottomans also dominated Black Sea trade, prompting Western Europeans to seek alternative oceanic routes to Asia.