17 Vedic Indian to the Fall of the Maurya Empire

Few areas of the world are as important to our understanding of the emergence of human civilizations as India. Its unique geography is divided into three distinct zones:

- The Himalayan North: A rugged and mountainous region that forms a natural barrier, separating India from the rest of the Asian mainland.

- The Indo-Gangetic Plains: A densely populated area, nestled between the Himalayas and the Deccan Plateau, where the Indus and Ganges Rivers flow. This fertile region has supported some of the world’s oldest and most influential civilizations.

- The Tropical South: A distinct and isolated zone, characterized by lush forests and mountain ranges, which separates it from the rest of India. This region has developed a unique cultural and ecological identity, shaped by its geographic isolation.

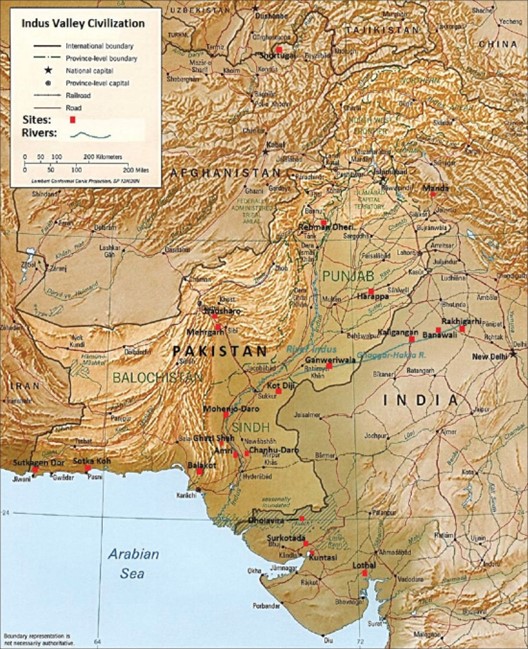

India’s geography shaped not only where people lived but how they interacted, governed, and expressed their spiritual lives. The Indus Valley Civilization, flourishing in the northwestern region from roughly 2600 to 1900 BCE, gave rise to complex cities, rich artistic traditions, and extensive trade networks. But by the early second millennium BCE, those cities had largely declined. Into this shifting landscape came a new wave of migrants—nomadic pastoralists from Central Asia—who would bring lasting changes to the culture, language, and religious practices of the subcontinent.

The Aryans and Brahmanism

The Aryans brought with them a spiritual tradition centered on the Vedas—sacred texts composed of hymns, chants, and rituals—that laid the foundation for what would later evolve into Hinduism. These texts were orally transmitted and formed the basis of the Vedic religion, which emphasized fire sacrifices (yajnas), devotion to natural and cosmic deities, and the importance of upholding dharma, or moral order.

The Aryans venerated various gods, such as Indra, the god of storms and war, and Varuna, the god of cosmic order. These deities were often associated with natural forces and cosmic principles, rather than being worshipped as fixed, individualized figures in a permanent pantheon. Rituals played a central role in Vedic life and helped reinforce social hierarchies, as only the Brahmins, or priestly class, were permitted to perform them. Over time, the increasing authority of the Brahmins led to the development of Brahmanism, a religious system that blended ritual power with philosophical inquiry.

Between 800 and 400 BCE, Brahmin scholars composed the Upanishads, a new collection of sacred texts that introduced profound philosophical concepts such as samsara (the cycle of rebirth), karma (the moral law of cause and effect), and moksha (liberation from the cycle of rebirth). These texts shifted emphasis away from ritual action alone and toward personal insight, meditation, and union with Brahman, the ultimate reality.

The belief in reincarnation and karma reinforced the idea that one’s current social position was the result of past actions. This worldview supported the emerging varna system, which classified society into four major social groups:

-

Brahmins (priests and scholars)

-

Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers)

-

Vaishyas (merchants and commoners)

-

Shudras (servants and laborers)

In its earliest form, the varna system was relatively fluid and allowed for some degree of social mobility. It provided a framework for social organization and a sense of identity, purpose, and responsibility. Each varna had specific duties (or dharma) that contributed to the functioning of society, helping to maintain harmony and interdependence among groups.

Over time, however, this system became more rigid and evolved into the jati system—a complex web of sub-castes with strict rules governing marriage, social interaction, and occupation. While the caste system reinforced inequality, it also preserved skills, professions, and religious traditions within distinct communities. For many, the sense of belonging to a jati brought structure, continuity, and spiritual meaning.

The promise of moksha offered an ultimate spiritual goal that transcended social divisions. Even though the caste system supported elite control—especially that of the Brahmins—it also gave individuals a reason to accept their social role as part of a larger cosmic order, with the possibility of future liberation.

The arrival of the Aryans and the gradual development of Brahmanism into Hinduism created a deeply influential social and religious framework. Despite its challenges, this system contributed to the cultural richness, continuity, and stability of early Indian civilization—and its legacy still shapes South Asian society today.

Link to Learning

Learn more about the Hindu religion by reading Dr. Mack’s chapter on Hinduism in his book, Religions of the World: Introduction.

Buddhism

Around 563 BCE, the life of Siddhartha Gautama, known as Buddha Sakyamuni, profoundly transformed Indian culture, religion, and art. Born into a royal family in the region that is now Nepal, Sakyamuni abandoned a life of luxury to embark on a spiritual quest for understanding and liberation from suffering. His teachings offered an alternative to the dominant Brahmanist traditions, earning him the title “Buddha,” meaning “the enlightened one.”

Buddhism explores human suffering, desire, and death, offering a path to overcome pain and achieve enlightenment. The Four Noble Truths diagnose the human condition, acknowledging the existence of suffering, its causes, and its cessation. The Eightfold Path provides a practical guide for individuals to develop wisdom, ethics, and mental discipline. This path emphasizes the importance of mindfulness, meditation, and self-reflection in achieving spiritual growth. By following the Eightfold Path, individuals can develop a deeper understanding of themselves and the world, leading to greater peace and compassion.

Link to Learning

Learn more about the Buddhist beliefs and practices by reading Dr. Mack’s chapter on Buddhism in his book, Religions of the World: Introduction.

Buddha’s teachings challenged ancient India’s status quo, questioning Brahmanist authority and ritualism, proposing instead a direct and personal approach to spiritual development. This critique resonated with many, including women and lower castes, who found in Buddhism a more accessible and egalitarian path. Buddhism offered women opportunities for enlightenment, but also had limitations and contradictions in its treatment of women. Despite these limitations, Buddhism provided a more inclusive and compassionate alternative to Brahmanism, which had traditionally marginalized certain groups. By challenging social norms and religious authority, Buddhism created a more diverse and dynamic spiritual landscape in ancient India.

Buddhism did not replace Brahmanism but influenced its evolution into what became Hinduism. Over time, the boundaries between the two religions became more fluid, allowing for coexistence and mutual influence. Brahmanism gradually incorporated some Buddhist ideas and practices, such as meditation, while Buddhism adopted certain elements of Brahmanism, leading to a more devotional form of religion that emphasized personal worship and prayer. Over time, Hinduism emerged as a distinct religion, incorporating elements from both Brahmanism and Buddhism, and becoming a dominant force in Indian spirituality.

Both Buddhism and Hinduism diversified into various schools and sects, adapting to different cultural and regional contexts. Institutionalized Buddhism, particularly in its Mahayana form, attracted significant patronage from elites, inspiring monumental architecture, sculpture, and art throughout Asia. Buddhism’s influence spread widely, reaching millions of people across China, Korea, Japan, Thailand, and Southeast Asia, where it remains a major religious tradition to this day.

The Mauryan Empire

The Mauryan Empire, which emerged in 322 BCE, played a crucial role in the spread of Buddhism across Asia. Founded by Chandragupta Maurya, who unified much of north India, the empire was marked by a complex political structure and a strong military presence. The Mauryan rulers, who governed a vast and diverse population, relied on a large army and a well-organized bureaucracy to maintain control. However, they lived in constant fear of assassination and relied on a network of spies to monitor officials throughout the empire. Despite these challenges, the Mauryan Empire reached its peak during the reign of Emperor Ashoka, who ascended to the throne in approximately 268 BCE.

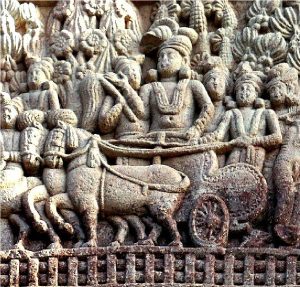

A stone relief showing Ashoka visiting a Buddhist pilgrim site.

(attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

Ashoka’s transformation from a ruthless warrior general to a devout man of peace was a gradual process, influenced by his experiences in the Kalinga War. The devastating consequences of the war, including the loss of over 100,000 lives, led Ashoka to question the true cost of his military victories. He eventually converted to Buddhism and dedicated his life to promoting peace, harmony, and compassion throughout India. Ashoka’s reforms aimed to create a more just and equitable society, with protections for vulnerable populations, including the ill, the poor, and travelers. He also supported missionary efforts to spread Buddhism to neighboring countries, including Burma and Sri Lanka.

Ashoka’s leadership exemplifies the power of perspective-taking. By immersing himself in the teachings of Buddhism, Ashoka gained a new perspective on the suffering and humanity of his enemies, leading him to question the true cost of his military victories. He began to see the world from the perspective of his subjects, understanding their struggles and aspirations, and adapted his policies to promote their well-being. Ashoka’s edicts, which addressed the needs and concerns of diverse populations, demonstrate his ability to take the perspectives of various groups and foster a sense of inclusivity and shared humanity. Through his commitment to perspective-taking, Ashoka was able to create a more just and harmonious society, one that valued the dignity and worth of all individuals.

The Mauryan Empire’s legacy is visible in its impressive architectural achievements, including the construction of hospitals, roads, and resthouses. Ashoka’s commitment to Buddhism and his efforts to promote peace and harmony throughout India helped establish the Mauryan Empire as a major center of Buddhist learning and culture. The empire’s influence extended far beyond India’s borders, shaping the development of Buddhism in neighboring countries and leaving a lasting impact on the ancient world. Despite its eventual decline, the Mauryan Empire’s impact on Indian history and culture remains significant, inspiring future generations to strive for peace, compassion, and understanding.

Core Impact Skill — Intercultural Competence

As you explore the rise of the Mauryan Empire, take a moment to appreciate how one of India’s most powerful dynasties helped shape the cultural and spiritual connections across Asia. Founded in 322 BCE by Chandragupta Maurya, the empire unified much of northern India and ruled over a diverse population through a complex bureaucracy, a large standing army, and a widespread system of surveillance. Yet it was under Emperor Ashoka—a ruler transformed by the trauma of war—that the empire became a beacon of Buddhist values and moral leadership.

Intercultural competence means recognizing that even powerful leaders are shaped by the cultures they encounter—and that understanding other perspectives can lead to profound change. After the Kalinga War, Ashoka rejected violence and embraced Buddhism. He began to govern with compassion, issuing edicts to protect the vulnerable, promote religious tolerance, and extend hospitality to strangers. His support for Buddhist missionaries helped spread these values to distant lands, including Sri Lanka and Burma, leaving a cultural legacy that reached far beyond India’s borders.

-

How did Ashoka’s personal transformation after the Kalinga War allow him to see the world differently—and reshape his empire in response?

-

What do Ashoka’s edicts tell us about the values he wanted to promote across a multicultural society?

-

How did the Mauryan Empire’s promotion of Buddhism influence the development of religious life in other regions?

By studying the Mauryan Empire and Ashoka’s commitment to empathy and ethical rule, we gain insight into how understanding others can lead to more inclusive leadership. That’s the heart of intercultural competence.

The Gupta Dynasty

The Gupta Dynasty, which ruled northern India from the fourth to the seventh centuries (320-600 CE), marked a golden age of cultural and intellectual flourishing. Founder Chandragupta I (r. 320-335 CE) emulated the Mauryans, promoting learning and the arts through Sanskrit scribes. This era saw the development of classical literature, including the Mahabharata and Ramayana, which glorified ideals of duty, valor, and social role. These texts had a profound impact on Indian society, shaping notions of noble virtues and ideal governance. Additionally, the Guptas patronized scholars and poets, leading to a resurgence in Sanskrit literature and learning.

Learn More

You can read a brief synopsis of the Ramayana and a description of the epic’s major characters (https://openstax.org/l/77RamayanaSyn) at the British Library website.

An animated English-language version of the epic (https://openstax.org/l/77RamayanaVid) is also available.

The Gupta era brought major advancements in mathematics, led by thinkers like Brahmagupta (fl. 598–665 CE), who introduced the use of decimals, zero, and negative numbers. His influential texts, including the Brahmasphuta Siddhanta, shaped Indian mathematics and astronomy for generations. During this period, Sanskrit classics spread across Southeast Asia, expanding India’s cultural reach. Politically, the Guptas strengthened their control by granting land to powerful families and Brahmans, reinforcing their status through rituals dedicated to Vishnu and Shiva. These strategies created a complex system of governance in which the Guptas balanced their authority with that of local rulers and Brahmanical elites.

Religious life also underwent transformation. The rise of personalized worship allowed devotees to connect directly with deities, reducing reliance on Brahman intermediaries. This shift gained particular momentum in southern India, where Tamil poets like Appar and Sambandar (both c. 7th century CE) composed foundational works celebrating devotional practices known as bhakti. Centered on love and personal devotion to a chosen deity, bhakti offered an alternative to formal Brahmanical rituals and reshaped the direction of Hinduism. At the same time, Buddhism flourished, with institutions like Nalanda University (founded in the 4th–5th century CE) attracting students and pilgrims from as far as China, making the Gupta period a high point for both intellectual and religious life in India.

Painted caves with beautiful sculptures found in the Ajanta caves illustrate the sophistication of the artists patronized by the dynasty. India’s educated classes ranked among the most learned and knowledgeable of the ancient world, and at times they turned their attention from math and morality to explore the depths of passion, love, and eroticism. During this period, the Kama Sutra, a treatise on courtship and sexuality, became a seminal piece of Indian literature, inspiring and titillating generations worldwide ever since.

The Gupta period’s opulence and stability eventually dissipated under the threat of northern invaders, the Huns (led by Toramana in the 6th century CE). Northern India fractured into smaller states, while southern India’s ties with South Asia deepened, leading to the formation of notable kingdoms like the Tamil Chola dynasty (c. 300 BCE-1279 CE). The Chola dynasty would go on to play a significant role in Indian history, patronizing art, literature, and architecture. India’s most influential exports – Hinduism, Buddhism, and their inspired art and learning – endured long after these states. The legacy of the Guptas can still be seen in the many temples, sculptures, and texts that survive from this period, a testament to their enduring impact on Indian culture.