[From African Folktales in the Fairy Books of Andrew Lang, originally published in The Crimson Fairy Book (1903), based on a story in Les Ba-Ronga: Étude ethnographique sur les indigènes de la baie de Delagoa by Henri Junod, 1898. See item #121 in the Bibliography. The illustration is by Henry Justice Ford.]

Once upon a time, in a very hot country, a man lived with his wife in a little hut which was surrounded by grass and flowers. They were perfectly happy together till, by and by, the woman fell ill and refused to take any food. The husband tried to persuade her to eat all sorts of delicious fruits that he had found in the forest, but she would have none of them, and she grew so thin he feared she would die. “Is there nothing you would like?” he said at last in despair.

Once upon a time, in a very hot country, a man lived with his wife in a little hut which was surrounded by grass and flowers. They were perfectly happy together till, by and by, the woman fell ill and refused to take any food. The husband tried to persuade her to eat all sorts of delicious fruits that he had found in the forest, but she would have none of them, and she grew so thin he feared she would die. “Is there nothing you would like?” he said at last in despair.

“Yes, I think I could eat some wild honey,” answered she. The husband was overjoyed, for he thought this sounded easy enough to get, and he went off at once in search of it.

He came back with a wooden pan quite full of wild honey and gave it to his wife. “I can’t eat that,” she said, turning away in disgust. “Look! There are some dead bees in it! I want honey that is quite pure.” And the man threw the rejected honey on the grass and started off to get some fresh.

When he got back, he offered it to his wife, who treated it as she had done the first bowlful. “That honey has got ants in it; throw it away,” she said, and when he brought her some more, she declared it was full of earth.

In his fourth journey he managed to find some that she would eat, and then she begged him to get her some water. This took him some time, but at length he came to a lake whose waters were sweet. He filled a pannikin quite full and carried it home to his wife, who drank it eagerly and said that she now felt quite well.

When she was up and had dressed herself, her husband lay down in her place, saying, “You have given me a great deal of trouble, and now it is my turn!”

“What is the matter with you?” asked the wife.

“I am thirsty and want some water,” answered he, and she took a large pot and carried it to the nearest spring, which was a good way off. “Here is the water,” she said to her husband, lifting the heavy pot from her head, but he turned away in disgust.

“You have drawn it from the pool that is full of frogs and willows; you must get me some more.” So the woman set out again and walked still further to another lake.

“This water tastes of rushes,” he exclaimed. “Go and get some fresh water.” But when she brought back a third supply he declared that it seemed made up of water-lilies and that he must have water that was pure, and not spoilt by willows, or frogs, or rushes.

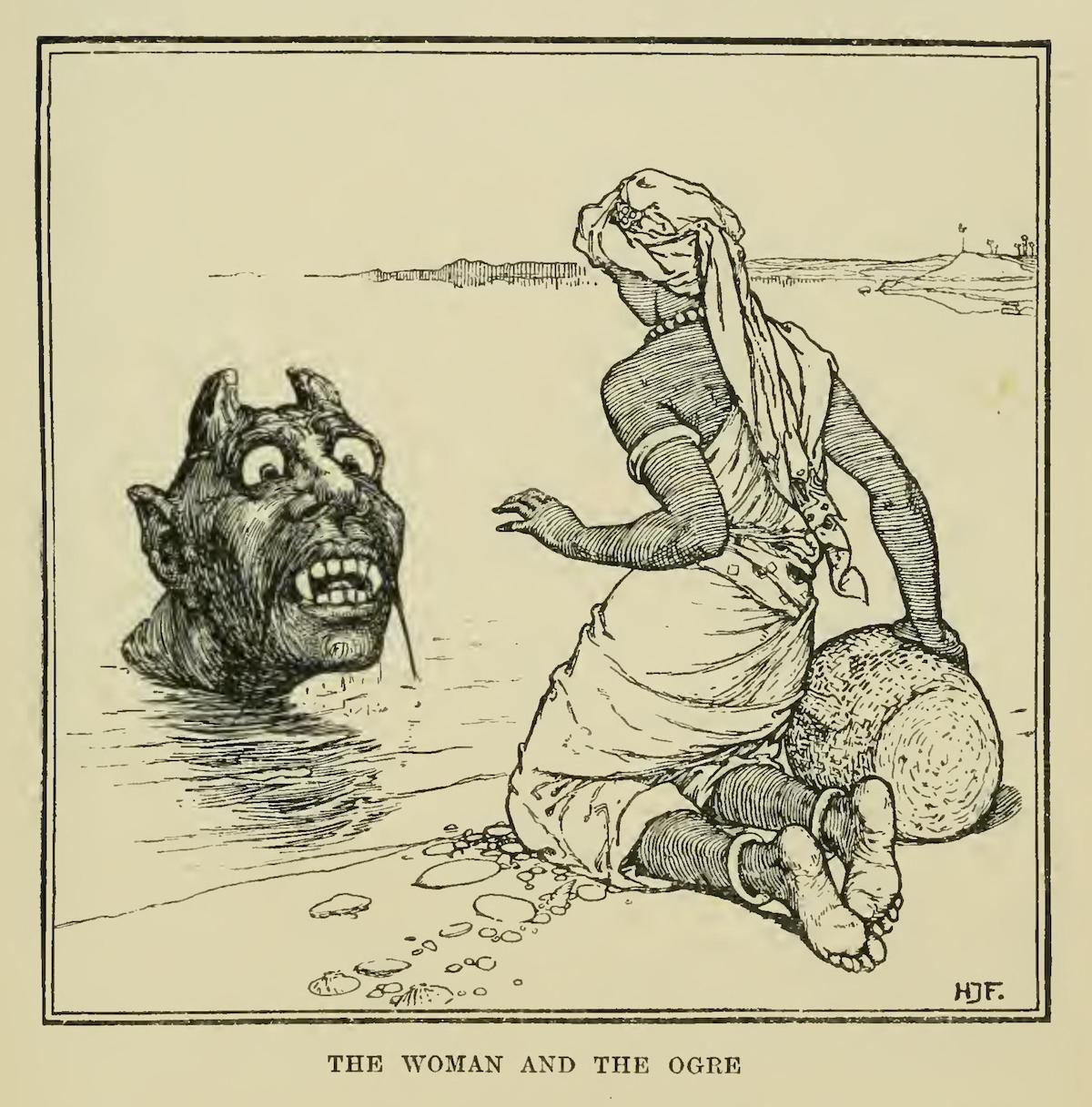

So for the fourth time she put her jug on her head and, passing all the lakes she had hitherto tried, she came to another where the water was golden and sweet. She had stooped down to drink when a horrible head bobbed up on the surface.

“How dare you steal my water!” cried the head.

“It is my husband who has sent me,” she replied, trembling all over. “But do not kill me! You shall have my baby, if you will only let me go.”

“How am I to know which is your baby?” asked the ogre.

“Oh, that is easily managed. I will shave both sides of his head and hang some white beads round his neck. And when you come to the hut, you have only to call ‘Motikatika!’ and he will run to meet you, and you can eat him.”

“Very well,” said the ogre, “you can go home.” And, after filling the pot, she returned and told her husband of the dreadful danger she had been in.

Now, though his mother did not know it, the baby was a magician, and he had heard all that his mother had promised the ogre, and he laughed to himself as he planned how to outwit her.

The next morning she shaved his head on both sides, and hung the white beads round his neck, and said to him, “I am going to the fields to work, but you must stay at home. Be sure you do not go outside, or some wild beast may eat you.”

“Very well,” answered he.

As soon as his mother was out of sight, the baby took out some magic bones and placed them in a row before him. “You are my father,” he told one bone, “and you are my mother. You are the biggest,” he said to the third, “so you shall be the ogre who wants to eat me, and you,” to another, “are very little; therefore you shall be me. Now then, tell me what I am to do.”

“Collect all the babies in the village the same size as yourself,” answered the bones. “Shave the sides of their heads, and hang white beads round their necks, and tell them that when anybody calls ‘Motikatika,’ they are to answer to it. And be quick, for you have no time to lose.”

Motikatika went out directly, and brought back quite a crowd of babies, and shaved their heads, and hung white beads round their little necks, and, just as he had finished, the ground began to shake, and the huge ogre came striding along, crying, “Motikatika! Motikatika!”

“Here we are! Here we are!” answered the babies, all running to meet him.

“It is Motikatika I want,” said the ogre.

“We are all Motikatika,” they replied. And the ogre sat down in bewilderment, for he dared not eat the children of people who had done him no wrong, or a heavy punishment would befall him. The children waited for a little, wondering, and then they went away.

The ogre remained where he was till the evening when the woman returned from the fields.

“I have not seen Motikatika,” said he.

“But why did you not call him by his name as I told you?” she asked.

“I did, but all the babies in the village seemed to be named Motikatika,” answered the ogre. “You cannot think the number who came running to me.”

The woman did not know what to make of it, so, to keep him in a good temper, she entered the hut and prepared a bowl of maize, which she brought him.

“I do not want maize; I want the baby,” grumbled he, “and I will have him.”

“Have patience,” answered she. “I will call him, and you can eat him at once.” And she went into the hut and cried, “Motikatika!”

“I am coming, mother,” replied he, but first he took out his bones and, crouching down on the ground behind the hut, he asked them how he should escape the ogre.

“Change yourself into a mouse,” said the bones, and so he did, and the ogre grew tired of waiting and told the woman she must invent some other plan.

“Tomorrow I will send him into the field to pick some beans for me, and you will find him there and can eat him.”

“Very well,” replied the ogre, “and this time I will take care to have him,” and he went back to his lake.

Next morning Motikatika was sent out with a basket and told to pick some beans for dinner. On the way to the field, he took out his bones and asked them what he was to do to escape from the ogre. “Change yourself into a bird and snap off the beans,” said the bones. And the ogre chased away the bird, not knowing that it was Motikatika.

The ogre went back to the hut and told the woman that she had deceived him again and that he would not be put off any longer.

“Return here this evening,” answered she, “and you will find him in bed under this white coverlet. Then you can carry him away and eat him at once.”

But the boy heard and consulted his bones, which said, “Take the red coverlet from your father’s bed and put yours on his,” and so he did. And when the ogre came, he seized Motikatika’s father and carried him outside the hut and ate him.

When his wife found out the mistake, she cried bitterly, but Motikatika said, “It is only just that he should be eaten and not I, for it was he, and not I, who sent you to fetch the water.”