[From The Flame Tree and Other Folk-Lore Stories from Uganda by Rosetta Baskerville, 1900. See item #23 in the Bibliography. The illustration is by Mrs. E. G. Morris.]

Once upon a time, there was a little girl who lived in the village of Si in Kyagwe country. Her parents had no other children, and as she grew older they saw with joy that she was more beautiful every day. People who passed through the village saw her and spoke of her beauty until everyone in Kyagwe knew that the most lovely girl in the country lived in the village of Si — and everyone in the province called her “the Maiden.”

The Maiden was a gentle, sweet child, and she loved all the animals and birds and butterflies and flowers, and played with them and knew their language. Her parents were very proud of her, and they often talked of the time when she should be grown up and marry a great chief with many cows and gardens and people, and bring great wealth to her tribe.

When the time came to arrange her marriage, all the chiefs came and offered many gifts, as the custom of the Baganda is, but the Maiden said, “I will marry none of these rich chiefs; I will marry Tutu the peasant boy, who has nothing, because I love him.” Her parents were very grieved when they heard this and would have tried to persuade her, but just then a messenger arrived from the local chief to say that the King of Uganda was going to war with Mbubi, the Chief of the Buvuma Islands, and all the chiefs went away to collect their people for the king’s army.

Then the Chief of Si called all his men together, and Tutu the peasant boy went with them. The army marched down to the Lake shore to fight the Islanders who came across the blue waters in a fleet of war canoes, painted and decorated with horns and feathers and cowry shells and beads. The Maiden was very sad when she said good-bye to Tutu. “Be very brave and win glory,” she said. “Then my father will let me marry you, for I will never marry anyone else.”

But when the men had marched away and only the women and children were left in the village with the old people, the Maiden forgot her brave words and only thought how she could bring Tutu safely back. She called to her friend the hawk. “Come and help me, Double-Eye; fly quickly to the Lake shore and see my peasant boy — tell him I think of him day and night. I cannot be happy till he returns.”

The hawk knew Tutu well, for often on the hillside he saw how Tutu had played with the children (the Baganda call the hawk “Double- Eye,” for they say that with one eye he watches the Earth and with the other he sees where he is going).

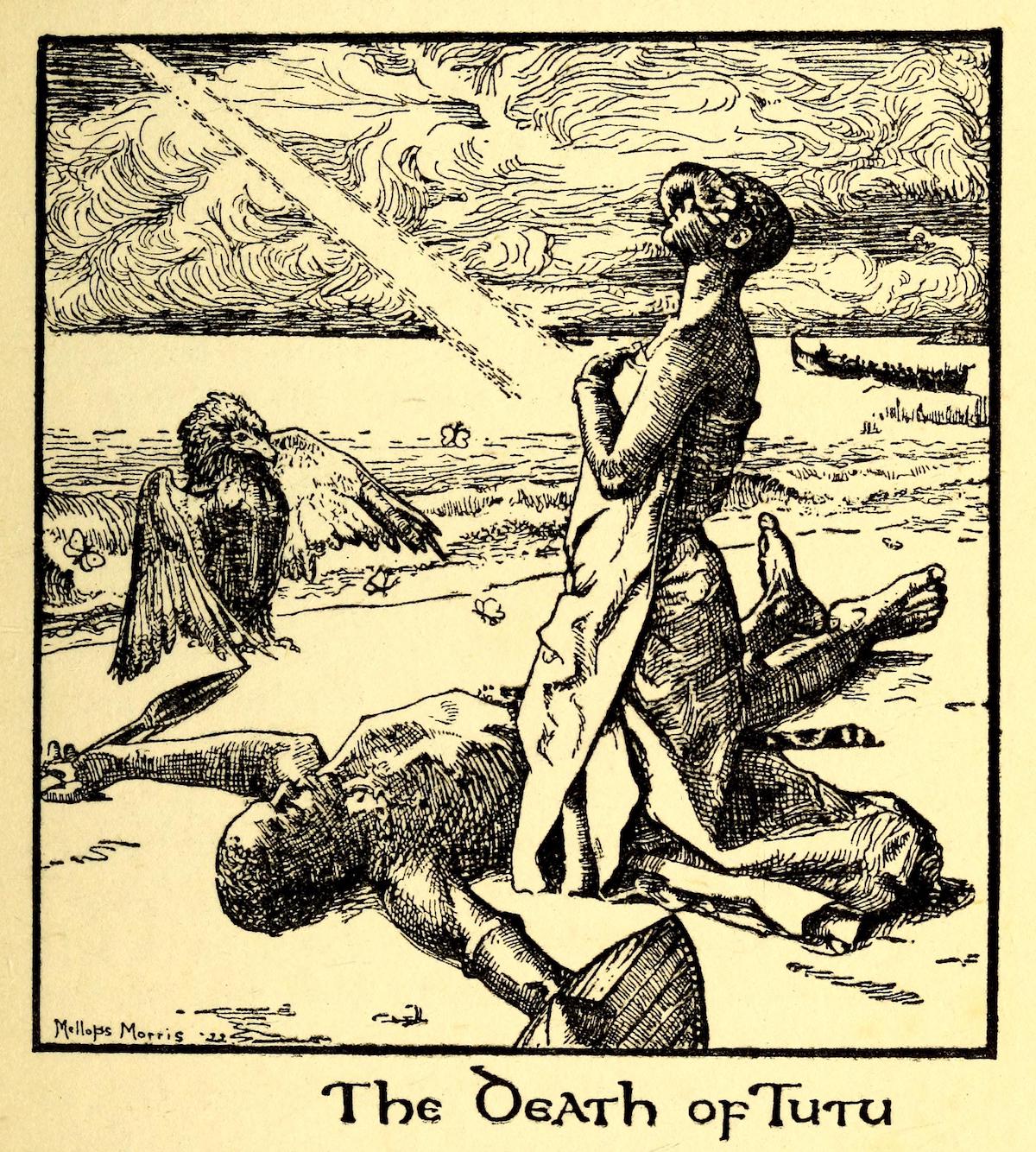

The Baganda reached the Lake, and there was a great battle, and Tutu the peasant boy was killed by a stone from an Islander’s sling, but the Baganda rallied and drove the enemy back to their canoes, and Mbubi beat the retreat drum and his men returned to Buvuma.

The hawk flies very quickly, and while he was still a long way off, he saw Tutu lying where he had fallen on the Lake shore. The soldiers were burying the dead, and the hawk watched to see where they would bury the peasant boy of Si so that he might show the Maiden his grave.

Meanwhile, the Maiden waited on the hillside for the hawk’s return, and the moments seemed like hours. She called to a bumblebee who was her friend. “Go quickly to the Lake side and greet my peasant boy; tell him I wait here on the hillside for his return.”

The bumblebee flew away quickly, and when he reached the Lake shore, he asked the hawk for news.

“The Islanders have fled in their canoes,” said the hawk, “but Tutu the peasant boy is dead; a stone from a sling killed him. I wait to see his grave so that I may show it to the Maiden.”

The bumblebee was afraid to go back with the news, so he stayed near the hawk and watched.

Meanwhile the Maiden waited in a fever of impatience, ever gazing at the distant Lake while pacing up and down. She saw a flight of white butterflies playing hide-and-seek round a mimosa bush and called to them. “Oh, white butterflies, how can you play when my heart is breaking? Go to the Lake shore and see if my peasant boy is well.”

So the white butterflies flew away over the green hills to the Lake and arrived on the battlefield just as the soldiers were digging Tutu’s grave, and they settled sadly down on a tuft of grass, their wings drooping with sorrow, for they loved the Maiden who had often played with them in the sunshine.

Far away on the Si hills, the Maiden watched in vain for their return. Filled with fear, she cried to the Sun, “Oh, Chief of the Cloud Land, help me! Take me on one of your beams to the Lake shore so that I may see my peasant boy and tell him of my love.”

The Sun looked down on her with great pity, for he had seen the battle and knew that Tutu the peasant boy was dead. He stretched out one of his long beams, and she caught it in her hands, and he swung her gently round until she rested on the Lake shore.

When she saw the soldiers lifting Tutu’s body to lay it in the grave, she cried to the Sun, “Oh, Chief of the Cloud Land, do not leave me! Burn me with your fire, for how can I live now that my Love is dead?”

Then the Sun was filled with pity and struck her with a hot flame, and the soldiers were very sorry for her too, and they dug a grave for her next to Tutu’s.

And when the people of Si visited the graves the next year, they found a wonderful thing, for a beautiful tree had grown out of the graves with large flame-coloured blossoms which ever turned upwards to the sun, and they took the seeds and planted them in their gardens. And now the country is full of these beautiful trees which are called Flame Trees, but the old people call them Kifabakazi because the stem is as soft as a woman’s heart and a woman can cut it down.