[From Native Fairy Tales of South Africa by Ethel McPherson, 1919. See item #138 in the Bibliography. The illustration is by Helen Jacobs.]

At the entrance to a kraal, a boy sat watching the sunset. He was thin and small. The other children were laughing and shouting, but he did not join in their play, for his heart was sore. He had had no supper, and the women of the kraal were all so busy looking after their own children that they had forgotten him. The boy’s mother had died when he was a babe, and ever since he had been driven from one hut to another. His father was out all day hunting and snaring birds, and when he came back at sundown, he seldom spoke to his little son. That day, one of the women had beaten him because the load of firewood which he had brought back was small, and his heart was hot with anger.

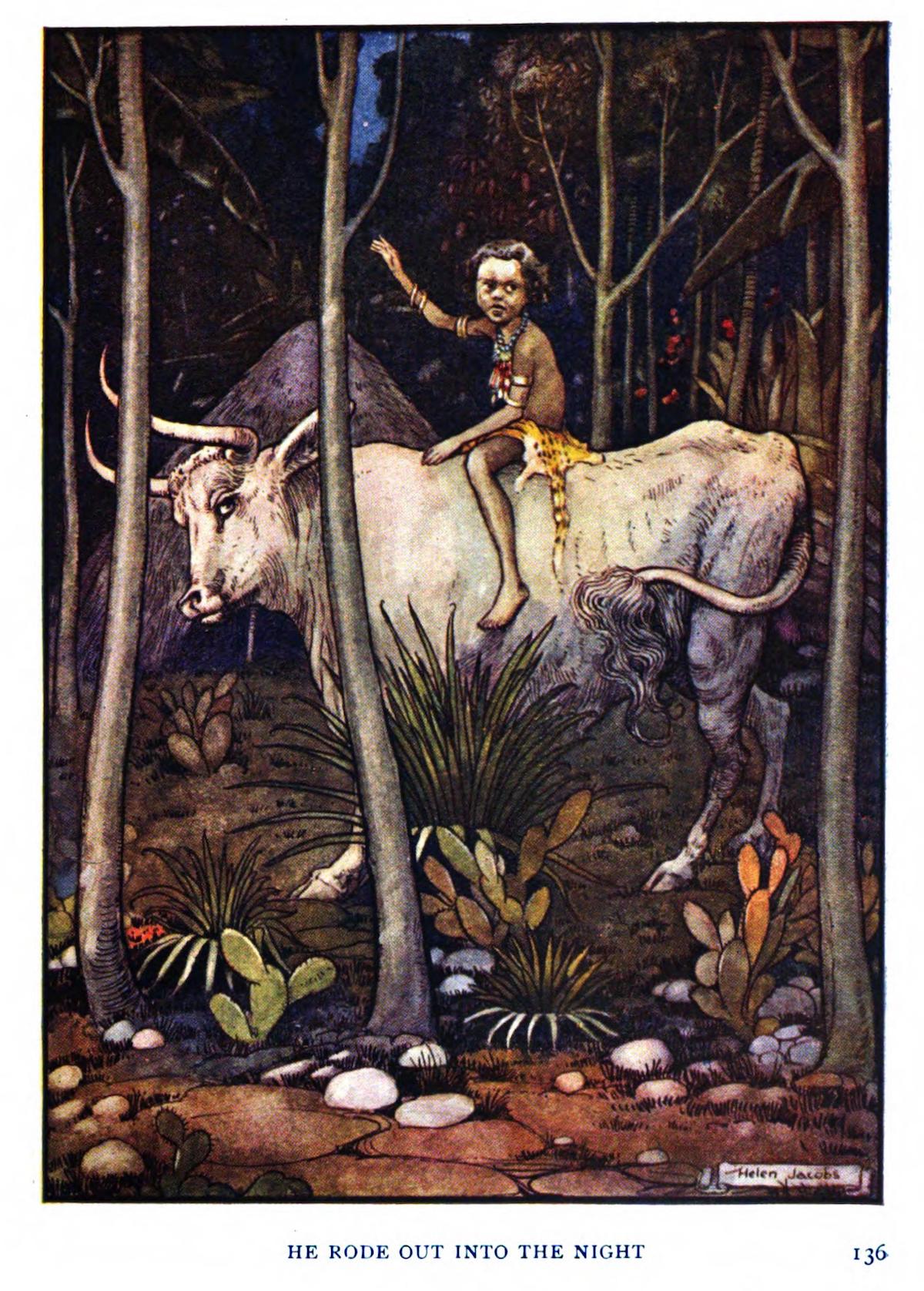

“I will go away and never come back,” he said to himself. So when darkness settled over the land and all were sleeping, he rose from the ground and, going to the cattle-shed, he took one of his father’s oxen. Having mounted it, he rode out into the night.

He did not know where he was going, but he wanted to leave behind him all the women who were so cruel to him and who let him hunger.

When he was far from the kraal, he got down from the ox and lay under a tree. He slept until the sun came up again over the edge of the world. Then he continued his journey, rejoicing at being far away from those who had ill-treated him.

By and by, he noticed a cloud of dust on the horizon, and presently he saw that it was caused by the feet of a herd of cattle coming toward him. At the head of the herd was a great bull, fierce and strong of aspect.

“Get down from my back,” said the ox he was riding. “I am going to fight the bull, but have no fear, for it is I who will be the victor. ”

The boy dismounted and stood aside to watch the fight between the two strong beasts, who ran at one another with heads lowered and with angry bellowings, pawing the ground till they were hidden from sight in the cloud of dust raised by their trampling feet. The struggle was long and fierce, but at last the ox overthrew his foe, as he had foretold. Then he bade the boy mount again, and once more they went on their way.

As the day wore on, the boy grew hungry. The ox said to him, “Strike my right horn, and food will come forth.”

The boy did as he was commanded, and there came forth meat and drink, and he ate till his hunger was satisfied.

When he had finished his meal, the ox said, “Strike my left horn.”

The boy obeyed, and the food still remaining entered the horn.

All through the long hot day they journeyed across the veld till, when the sun was low, the boy saw another herd of cattle coming toward them, led by a bull even stronger than the one which they had encountered that morning.

Wearied with the long march and the struggle with his first foe, the ox walked with a slow and heavy tread. But he bade the boy once again dismount, saying, “I am going to fight with yonder bull. I shall be overthrown and death will take me, but have no fear. When I am dead, remove my horns and carry them with you wherever you go, for they will give you food and drink when you are hungry and thirsty.”

The boy dismounted and, summoning all his strength, the ox rushed toward his foe with lowered head. The fight was long and fierce — fiercer far than the struggle of the morning, but victory was not to the ox, and with a deep groan he sank dead upon the earth.

The boy’s heart was sad at the loss of his friend but, remembering the ox’s command, he took the horns from his head and went his way.

Night fell, but he journeyed on till he came to a hut where he found a man dwelling by himself. The boy asked for a night’s lodging, and the man bade him welcome but said that he could give him no food, for famine had fallen upon the countryside, and everywhere men hungered, eating weeds instead of corn.

The boy laughed. “I have something better to offer you than weeds,” he said.

Thereupon he struck the right horn of the dead ox. Forthwith it yielded meat and drink in abundance, and they ate and were satisfied. Then the boy stretched himself on the ground and slept soundly, but the man, who had known the pinch of hunger for many a weary day, lay awake thinking how he might deceive the boy and secure for himself the bountiful horns. At last among the lumber in the hut he found two horns which exactly resembled those his guest had brought, and he laid them beside the sleeping lad, taking away those which belonged to the boy by right.

At daybreak, the boy was ready to start on his travels once more and, suspecting no evil, he picked up the horns that lay beside him and journeyed toward the rising sun.

When the sun beat down fiercely upon the plain at noon, he sought the shadow of a rock and struck the horn, expecting that as before it would satisfy his need, but no food came.

He struck twice and thrice; then, guessing that his host of the night before had robbed him, he retraced his steps and reached the hut just as the sun was setting. He paused outside and listened; the man was begging the horn to give him food, but the horn, answering to no voice save that of its real owner, remained sealed. Then the boy entered and, fearing his vengeance, the man ran out into the night, nor did he return. The boy made a good meal of the food which the horn supplied to him and lay down to rest.

Next morning he once more set out, and at nightfall he saw a hut standing by itself on the plain. He went up and boldly asked the man who dwelt there for a night’s lodging, but he got a rude answer, for he was dusty and travel-stained, and the owner of the hut had no mind to entertain a vagabond.

Hurt by the man’s roughness, the boy wandered farther till he came to a river in which he bathed his dusty limbs. Then he struck the horn, for he was hungry as well as weary, and from it there came not only meat and drink, but a mantle of skins and ornaments of brass, such as those worn by the sons of a chief. Clad thus, the next day the boy traveled farther on till he reached a village, and at the sight of the stranger in such regal attire, the headman came forward and bade him to a feast. He was treated with all honour and remained with the headman for many days.

Now the headman had a beautiful daughter and, seeing how fair she was and how gentle, the boy loved her, and the girl’s heart answered to his. This being so, her father ordered oxen to be slain and a great feast prepared to celebrate their marriage.

Ever after they lived in peace and plenty, for the horns never failed to yield food and raiment, and all good things in abundance.