[From Native Fairy Tales of South Africa by Ethel McPherson, 1919. See item #138 in the Bibliography. The illustration is by Helen Jacobs.]

At the foot of a high mountain there dwelt a man who had two daughters, the elder of whom was named Kazi and the younger Zanyani. Kazi was a tall, beautiful girl, but she was selfish and bad-tempered and always quarreling with her father and Zanyani. She was lazy, too, and never took her share of the work, but left Zanyani to gather the firewood, draw the water, and mend the thatch of the hut. If she could help it, she would never grind the corn, and when she baked the bread, it was always burnt to cinders.

In fact, Kazi was so disagreeable and troublesome that as soon as she was grown up, her father determined to find her a husband so he and Zanyani might be able to live in peace.

One day he set out upon a journey, leaving the girls to take care of themselves. When he came to the village to which he was bound, he got through his business as quickly as he could and then went to drink beer and talk with his friends.

They told him all the news of the village — how there had been a swarm of locusts which had eaten half the crops, how a leopard had come down from the hills and killed three sheep, and, most exciting of all, that the chief wanted a wife. The chief of this village was a great and powerful ruler, but he had never been seen by his people. Some said that he had five heads, each with cruel jaws and a pointed tongue, and that he ate all who angered him.

When Kazi’s father heard that the chief was looking for a wife, he said to himself that his elder daughter would be just the right bride for him since she was so proud and so self-willed that she would never allow him to bully her, while she was so haughty that he knew she would never consent to marry anyone less than a chief.

When he reached home again, he said to his daughters, “Which of you would like a chief for a husband?”

“I would,” said Kazi, not giving Zanyani a chance to speak.

“Let it be so,” answered the father. “Tomorrow I will call together my friends, and we will escort you to a great chief who is seeking a wife.”

“I do not want you or your friends,” answered Kazi rudely. “I will go by myself.”

At this her father was angry, for it was not fitting that a daughter of his should go unattended to her bridegroom, or without an ox for the wedding feast. Knowing, however, that it were easier to check the wind in its course than to tame the will of his daughter, he bade her do as she pleased.

Early next morning Kazi rose and adorned herself with her anklets and armlets of brass, hanging round her throat a necklace of bright-coloured beads. When she looked at her image in the clear pool beside the hut, she laughed with pleasure, for in truth she was fair enough to win the heart of any man, even if she came to him empty-handed.

Then she ran back to the hut and, having filled a basket with bread and wild fruit, she set out on her journey. The sun was rising over the edge of the veld, touching the hill-tops with golden light; the air was frosty, and Kazi ran as quickly as her feet could carry her till the blood tingled in her veins, and she began to sing for gladness. She cared nothing for her father’s displeasure. Why should not she, the beautiful Kazi, go unattended to the village of her bridegroom? Let girls less fair than she take gifts of oxen; let these, if they chose, go escorted by their fathers and the village folk!

When she was a league or so from home, Kazi sat down beside a tall aloe to eat her morning meal and to bask in the warm sunshine.

By and by, something touched her foot and, glancing down, she saw a mouse which looked up at her as if it had something to say.

“What is it, little sister?” she asked, and the mouse replied, “Shall I show you the way to the chief?”

Kazi laughed scornfully and said, “Go away, you foolish little creature. Do you think I cannot find my way to him without the help of a little brown mouse like you?” And she pushed it roughly from her.

“If you go alone, you will meet with trouble,” said the mouse, but Kazi only laughed, and the small creature ran away.

When she was rested, Kazi rose and continued her journey till she came to a brook which was overhung by trees. Sitting down on the bank, she put her feet into the cool running water. It was now noon, and the warm silence was unbroken save for the croaking of the frogs. Feeling much refreshed, Kazi again went on her way.

By and by, she saw an old woman sitting on a stone by the wayside. The old woman greeted her and said, “I know who you are and where you are going, and therefore I give you warning. Toward sunset you will come to a wood where the trees grow thick as the blades of grass. When you enter this wood, they will mock you with their laughter, but heed them not, for they cannot hurt you unless you laugh back. If you do, then beware, for harm will befall you. On the edge of the wood you will see a calabash of amasi lying on the ground, but no matter even if you are faint with hunger, touch it not. When you have gone farther, you will meet a man carrying a pot of water, and he will offer you a draught, but though your tongue cleave to the roof of your mouth, beware of letting a drop pass your lips.”

“First a mouse, and now an old woman,” said Kazi, tossing her head. “What wise counselors! Thank you for your good advice, but I shall do just as I please!”

The old woman made no answer, and Kazi went her way, singing defiantly. By and by, she came to the wood of which she had been told, and in the gathering darkness she heard the sound of mocking laughter. She entered boldly, but soon her anger rose, for it seemed as if the trees were pointing their branches like long fingers and making fun of her.

The mocking laughter grew louder as she went deeper into the wood, and the trees bent and shook with merriment. Kazi grew still more angry. How dare they laugh at her expense! Were not all who knew her proud spirit afraid of her, and was she to be jeered at by trees? The wood was dark and thickly grown, and from its secret places came the cruel sound in rising notes. It was too much; Kazi stamped her foot in anger and then laughed back — a laugh as cruel and mocking as that of the trees.

For a moment there was silence, and so still was the air that the girl’s heart stopped beating. Thick darkness gathered round her, and there was a deep roll of thunder. Then from the depths of the wood came a peal of laughter, louder and more pitiless than before.

Kazi was so terrified that she began to run and never stopped till she reached the edge of the wood and found herself out on the open veld. Panting with fear, she lay down on the grass to rest and to regain her courage, and by and by, when she was refreshed, she sat up and looked about her. A few yards away lay a calabash of amasi, just as the old woman had foretold, but though Kazi remembered the warning, she did not heed it and eagerly drank the milk.

It was now almost dark, but Kazi had no mind to lie down to rest so near the wood of mocking laughter. So she continued her journey, and after she had gone some little distance, she saw coming toward her the strange figure of whom the old woman had spoken.

It was a sight to make anyone shake with fear, for as he drew near, Kazi saw that under one arm the man carried his head, and a water-pot under the other. He was bent almost double and walked with a strange, shuffling gait.

Kazi was a bold girl, but if she had not been determined to set at naught the old woman’s warning, she would have run away from him. Conquering her fears, she walked boldly up to him and asked him for a drink of water.

Without a word he handed her the calabash, and the girl drank, trembling the while, for the black eyes of the head which he carried under his arm rolled without ceasing, and its teeth chattered noisily.

When the man was out of sight, Kazi lay down and slept, and early next morning she made ready to enter the village where lived the chief whose bride she intended to be.

When the people saw the tall, beautiful stranger, they gathered round her, asking who she was and why she had come.

“I have come to be the wife of your chief,” she answered haughtily.

“But where is your escort, and where are your oxen? Who ever knew a bride come to her husband without a retinue? The chief is away and will not return till nightfall, but you had best go yonder into his hut and prepare his food.”

The women of the kraal then led the stranger to the empty hut and gave her corn to grind.

Now Kazi had always left the grinding of the corn to her sister, and because she was unaccustomed to the task, the flour was full of hard lumps. The next thing was to make the flour into cakes and put them to bake, but so careless was Kazi that she let them burn black.

“I can’t grind corn, and I can’t cook,” said she, “but what does it matter? For when I am the wife of the great chief, I shall do no work.”

It was now growing late, and Kazi went to the door of the hut to watch for the coming of her bridegroom. The moon had risen and was flooding the veld with light, but there was no sign of an approaching figure, and long did Kazi wait, wondering whence he would come.

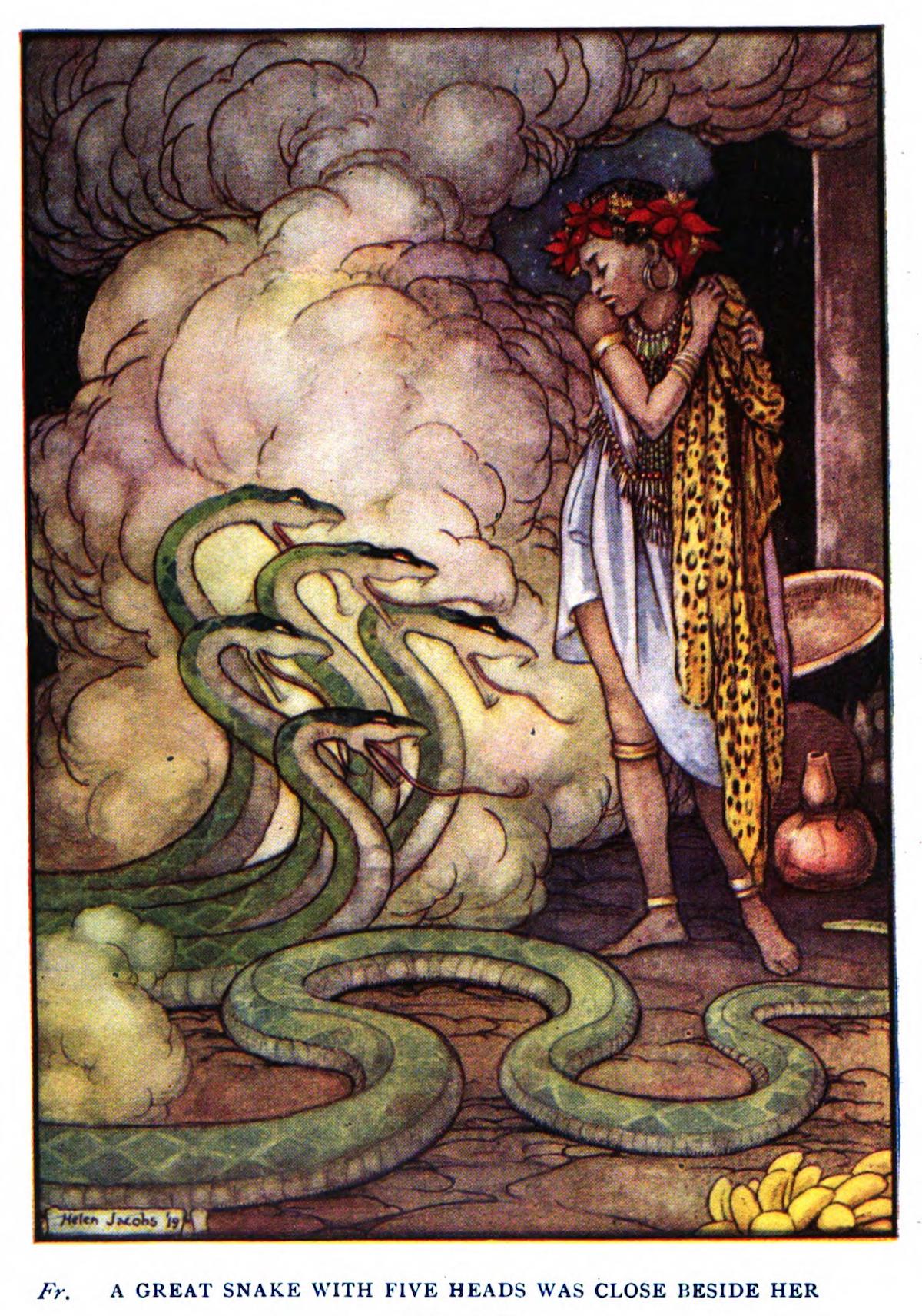

All at once the sky was darkened, and the hut was suddenly filled with a rushing wind. In a moment the storm ceased, and Kazi saw that a great snake with five heads was close beside her. In each of the five heads gleamed a pair of fiery eyes, which were fixed upon her.

“So you are my wife,” said the terrible being. The proud Kazi meekly bent her head and waited the pleasure of this horrible bridegroom.

“You are fair to look upon,” he said, “but bring me the cakes you have made ready for my supper. I am hungry.”

Kazi looked at the blackened cakes, and for the first time in her life she felt sorry that she was so poor a cook. Trembling, she laid them before the snake, who glanced at them with scorn.

“True,” he said, “you are fair to look upon, but you are a careless, idle woman,” and he struck her a blow which killed her.

About a year after Kazi’s death, news went round that the chief was again seeking a wife, and Zanyani’s father asked her whether she would like to be the bride. The girl consented, and her father chose from his herd a fat ox for slaughter at the wedding feast. Then he summoned his companions to escort the bride, and Zanyani, like a well-mannered maiden, raised no objection.

When all was ready, she set out, attended by her father and a procession of warriors in their bravery of waving plumes and brightly polished spears. As they went upon their way, they sang and rejoiced.

On the first part of the journey, they met with no adventures. They passed through the mocking wood, hearing no sound but the rustle of leaves, and no headless monster met them, but when they neared the village the little mouse ran out and stopped in front of the bride, saying, “Shall I show you the way?”

“If it please you, little sister, ” answered she, and the mouse guided them to a place where two roads met, and then it vanished into the bush.

At the crossroads the old woman was waiting, and she bade them follow the road to the left.

About half a mile from the village to which they were bound, the procession halted to rest, and Zanyani strayed a little from the path. Presently a girl carrying a water-pot came toward her and stopped to ask her who she was and why she thus wandered by herself.

“I have come to be the bride of the chief of yonder village,” she answered.

“He is my brother,” said the stranger. “Since you are to be my sister, let me tell you that, strange and fierce as he seems, he is gentle and good to those whom he loves, and you need not fear. Go to his hut with your father and the bridal escort,” she continued. “There my mother will give you corn to grind. When you have ground it, bake it into cakes, and if these are good, my brother will treat you well.”

Zanyani thanked the girl and took leave of her; then, returning to her father, she told him what had happened.

The journey was now resumed, and the procession escorted Zanyani to her husband’s hut. As the friendly stranger had said, the chief’s mother was waiting to receive her new daughter-in-law. She gave the bride corn to grind and then left her alone in the hut.

By and by, there lay ready a row of cakes made of fine flour, baked as only a skilled cook could bake them, and Zanyani sat down to wait the coming of the bridegroom.

Night fell, and presently there came the sound of a rushing wind, and the snake with five heads came forth. He glanced first at the bride and then at the cakes, and into his fierce eyes came a gentler light.

Having swallowed the cakes and finding them good, he turned to Zanyani, saying, “Are these of your baking?”

Zanyani bent her head in assent, and the horrible form began to change. From the scaly slough of skin that fell from him there rose a tall and handsome warrior. He looked tenderly upon the girl.

“You have freed me from the spell which has lain upon me this many a year,” he told her. “It could only be broken by the willing service of a gentle wife. ”

Then the chief came forth among his people, and the wedding was celebrated with feasting and joy.