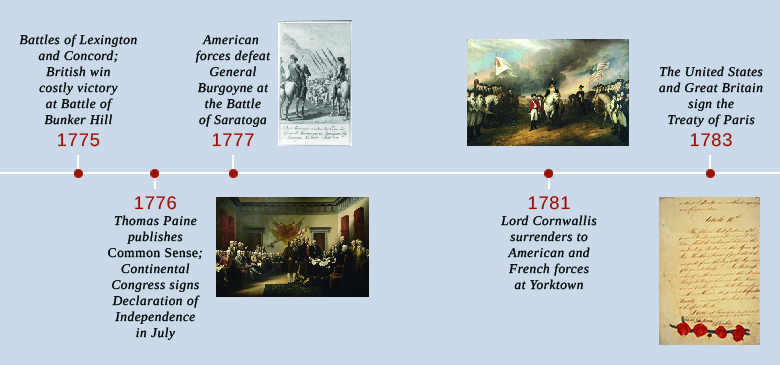

3 Chapter 3: Imperial Reforms, Colonial Protests, and the War that created a Nation, 1750-1783

Imperial Reforms, Colonial Protests, and the War that created a Nation, 1750-1783

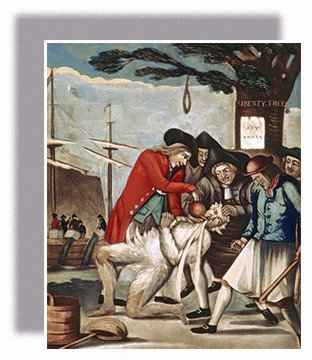

The Bostonians Paying the Excise-man, or Tarring and Feathering (1774), attributed to Philip Dawe, depicts the most publicized tarring and feathering incident of the American Revolution. The victim is John Malcolm, a Customs Official loyal to the British crown. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Chapter Outline

Introduction, Watch and Learn, Questions to Guide Your Reading

3.1 The Cost of War

3.2 The Stamp Act and the Sons and Daughters of Liberty

3.3 The Destruction of Tea and the Coercive Acts

3.4 Disaffection: The First Continental Congress and American Identity

3.5 Britain’s Law-and-Order Strategy and Its Consequences

3.6 The Revolution

3.7 Identity during the American Revolution

Summary Timelines, Chapter 3 Self-Test, Chapter 3 Key Terms Crossword Puzzle

Introduction

The Bostonians Paying the Excise-man, or Tarring and Feathering shows five Patriots tarring and feathering the Commissioner of Customs, John Malcolm, a sea captain, army officer, and staunch Loyalist. The Liberty Tree, an elm tree near Boston Common that became a rallying point against the Stamp Act of 1765, stands in the background of the print. When the crowd threatened to hang Malcolm if he did not renounce his position as a royal customs officer, he reluctantly agreed, and the protestors allowed him to go home. The scene represents the animosity toward those who supported royal authority and illustrates the high tide of unrest in the colonies after the British government imposed a series of imperial reform measures during the years 1763–1774.

The government’s formerly lax oversight of the colonies ended as the architects of the British Empire put these new reforms in place. The British hoped to gain greater control over colonial trade and frontier settlement as well as to reduce the administrative cost of the colonies and the enormous debt left by the French and Indian War. Each step the British took, however, generated a backlash. Over time, imperial reforms pushed many colonists toward separation from the British Empire.

By the 1770s, Great Britain ruled a vast empire, with its American colonies producing useful raw materials and profitably consuming British goods. From Britain’s perspective, it was inconceivable that the colonies would wage a successful war for independence; in 1776, they appeared weak and disorganized, no match for the Empire. Yet, although the Revolutionary War did indeed drag on for eight years, in 1783, the thirteen colonies, now the United States, ultimately prevailed against the British.

The Revolution succeeded because colonists from diverse economic and social backgrounds united in their opposition to Great Britain. Although thousands of colonists remained loyal to the crown and many others preferred to remain neutral, a sense of community against a common enemy prevailed among Patriots.

Watch and Learn (Crash Course in History videos for chapter 3)

- The Germantown Petition Against Slavery

- The Seven Years War and the Great Awakening

- Taxes & Smuggling: Prelude to Revolution

- Who Won the American Revolution?

- The American Revolution

Questions to Guide Your Reading

- Was reconciliation between the American colonies and Great Britain possible in 1774? Why or why not?

- Why did the colonists react so much more strongly to the Stamp Act than to the Sugar Act? How did the principles that the Stamp Act raised continue to provide points of contention between colonists and the British government?

- History is filled with unintended consequences. How do the British government’s attempts to control and regulate the colonies during this tumultuous era provide a case in point? How did the aims of the British measure up against the results of their actions?

- How did the colonists manage to triumph in their battle for independence despite Great Britain’s military might? If any of these factors had been different, how might it have affected the outcome of the war?

- How did the condition of certain groups, such as women, blacks, and Indians, reveal a contradiction in the Declaration of Independence?

- What was the effect and importance of Great Britain’s promise of freedom to enslaved people who joined the British side?

3.1 The Cost of War

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the French and Indian War and analyze the significance of this conflict

- Describe the size and scope of the British debt at the end of the French and Indian War and explain how the British Parliament responded to the debt crisis

Wars for empire connected the Atlantic sides of the British Empire. Great Britain fought four separate wars against Catholic France from the late 1600s to the mid-1700s. Another war, the War of Jenkins’ Ear, pitted Britain against Spain. These conflicts for control of North America also helped colonists forge important alliances with native peoples, as different tribes aligned themselves with different European powers.

Most imperial conflicts had both American and European fronts, leaving us with two names for each war. For instance, King William’s War (1688–1697) is also known as the War of the League of Augsburg. In America, the bulk of the fighting in this conflict took place between New England and New France. The war proved inconclusive, with no clear victor.

Queen Anne’s War (1702–1713) is also known as the War of Spanish Succession. England fought against both Spain and France over who would ascend the Spanish throne after the last of the Hapsburg rulers died. In North America, fighting took place in Florida, New England, and New France. In Canada, the French prevailed but lost Acadia and Newfoundland; however, the victory was again not decisive because the English failed to take Quebec, which would have given them control of Canada.

In North America, possession of Georgia and trade with the interior was the focus of the War of Jenkins’ Ear (1739–1742), a conflict between Britain and Spain over contested claims to the land occupied by the fledgling colony between South Carolina and Florida. The war got its name from an incident in 1731 in which a Spanish Coast Guard captain severed the ear of British captain Robert Jenkins as punishment for raiding Spanish ships in Panama. Jenkins fueled the growing animosity between England and Spain by presenting his ear to Parliament and stirring up British public outrage. More than anything else, the War of Jenkins’ Ear disrupted the Atlantic trade, a situation that hurt both Spain and Britain and was a major reason the war came to a close in 1742. Georgia, founded six years earlier, remained British and a buffer against Spanish Florida.

King George’s War (1744–1748), known in Europe as the War of Austrian Succession (1740–1748), was fought in the northern colonies and New France. In 1745, the British took the massive French fortress at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. However, three years later, under the terms of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, Britain relinquished control of the fortress to the French. Once again, war resulted in an incomplete victory for both Britain and France.

THE FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR

The final imperial war, the French and Indian War (1754–1763), known as the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) in Europe, proved to be the decisive contest between Britain and France in America. It began over rival claims along the frontier in present-day western Pennsylvania. Well-connected planters from Virginia faced stagnant tobacco prices and hoped expanding into these western lands would stabilize their wealth and status. Some of them established the Ohio Company of Virginia in 1748, and the British crown granted the company half a million acres in 1749. However, the French also claimed the lands of the Ohio Company, and to protect the region they established Fort Duquesne in 1754, where the Ohio, Monongahela, and Allegheny Rivers met.

This schematic map depicts the events of the French and Indian War. Note the scarcity of British victories. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The war began in May 1754 because of these competing claims between Britain and France. For the next decade, fighting took place along the frontier of New France and British America from Virginia to Maine. The war also spread to Europe as France and Britain looked to gain supremacy in the Atlantic World. The British fared poorly in the first years of the war (1754-57). However, the war began to turn in favor of the British in 1758, due in large part to the efforts of William Pitt, a very popular member of Parliament. Pitt pledged huge sums of money and resources to defeating the hated Catholic French, and Great Britain spent part of the money on bounties paid to new young recruits in the colonies, helping invigorate the British forces. In 1758, the Iroquois, Delaware, and Shawnee signed the Treaty of Easton, aligning themselves with the British in return for some contested land around Pennsylvania and Virginia. In 1759, the British took Quebec, and in 1760, Montreal.

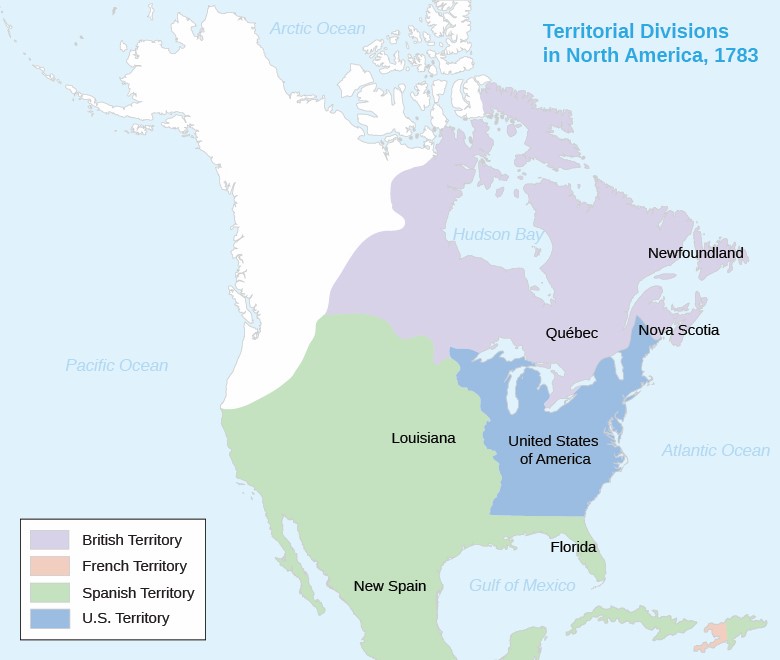

The war continued until 1763, when the French signed the Treaty of Paris. This treaty signaled a dramatic reversal of fortune for France. Indeed, New France, which had been founded in the early 1600s, ceased to exist. The British Empire had now gained mastery over North America. Great Britain’s victory in the French and Indian War meant that it had become a truly global empire. From Maine to Georgia, British colonists joyously celebrated the victory and sang the refrain of “Rule, Britannia! Britannia, rule the waves! Britons never, never, never shall be slaves!” In the American colonies, ties with Great Britain were closer than ever. Professional British soldiers had fought alongside Anglo-American militiamen, forging a greater sense of shared identity. With Great Britain’s victory, colonial pride ran high as colonists celebrated their identity as British subjects.

Despite the celebratory mood, the victory over France also produced major problems within the British Empire, problems that would have serious consequences for British colonists in the Americas. During the war, many Indian tribes had sided with the French, who supplied them with guns. After the 1763 Treaty of Paris that ended the French and Indian War (or the Seven Years’ War), British colonists had to defend the frontier, where French colonists and their tribal allies remained a powerful force. The most organized resistance, Pontiac’s Rebellion, highlighted tensions the settlers increasingly interpreted in racial terms.

The massive debt the war generated at home, however, proved to be the most serious issue facing Great Britain. The frontier had to be secure in order to prevent another costly war. Greater enforcement of imperial trade laws had to be put into place. Parliament had to find ways to raise revenue to pay off the crippling debt from the war. Everyone would have to contribute their expected share, including the British subjects across the Atlantic.

PROBLEMS ON THE AMERICAN FRONTIER

With the end of the French and Indian War, Great Britain claimed a vast new expanse of territory, at least on paper. British colonists, eager for fresh land, poured over the Appalachian Mountains to stake claims. The western frontier had long been a “middle ground” where different imperial powers (British, French, Spanish) had interacted and compromised with native peoples. That era of accommodation in the “middle ground” came to an end after the French and Indian War. Virginians (including George Washington) and other land-hungry colonists had already raised tensions in the 1740s with their quest for land. Virginia landowners in particular eagerly looked to diversify their holdings beyond tobacco, which had stagnated in price and exhausted the fertility of the lands along the Chesapeake Bay. They invested heavily in the newly available land. This westward movement brought the settlers into conflict as never before with Indian tribes, such as the Shawnee, Seneca-Cayuga, Wyandot, and Delaware, who increasingly held their ground against any further intrusion by white settlers.

Indians’ resistance to colonists drew upon the teachings of Delaware (Lenni Lenape) prophet Neolin and the leadership of Ottawa war chief Pontiac. Neolin was a spiritual leader who preached a doctrine of shunning European culture and expelling Europeans from native lands. Neolin’s beliefs united Indians from many villages. In a broad-based alliance, Pontiac led a loose coalition of these native tribes against the colonists and the British army.

Pontiac started bringing his coalition together as early as 1761, urging Indians to “drive [the Europeans] out and make war upon them.” The conflict began in earnest in 1763, when Pontiac and several hundred Ojibwas, Potawatomis, and Hurons laid siege to Fort Detroit. At the same time, Senecas, Shawnees, and Delawares laid siege to Fort Pitt. Over the next year, the war spread along the backcountry from Virginia to Pennsylvania. Pontiac’s Rebellion (also known as Pontiac’s War) triggered horrific violence on both sides. Firsthand reports of Indian attacks tell of murder, scalping, dismemberment, and burning at the stake. These stories incited a deep racial hatred among colonists against all Indians.

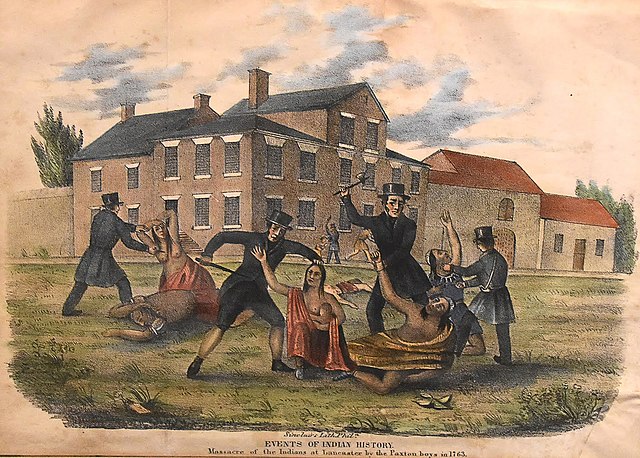

The actions of a group of Scots-Irish settlers from Paxton (or Paxtang), Pennsylvania, in December 1763, illustrates the deadly situation on the frontier. Forming a mob known as the Paxton Boys, these frontiersmen attacked a nearby group of Conestoga of the Susquehannock tribe. The Conestoga had lived peacefully with local settlers, but the Paxton Boys viewed all Indians as savages and they brutally murdered the six Conestoga they found at home and burned their houses. When Governor John Penn put the remaining fourteen Conestoga in protective custody in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, the Paxton Boys broke into the building and killed and scalped the Conestoga they found there). Although Governor Penn offered a reward for the capture of any Paxton Boys involved in the murders, no one ever identified the attackers. Some colonists, including Benjamin Franklin, reacted to the incident with outrage. Benjamin Franklin described the Paxton Boys as barbarous men who committed an atrocious act without regard to human or divine laws. Yet, as the inability to bring the perpetrators to justice clearly indicates, the Paxton Boys had many more supporters than critics.

This nineteenth-century lithograph depicts the massacre of Conestoga Indians in 1763 at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, by the Paxton Boys. None of the attackers were ever identified. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Both Pontiac’s Rebellion and the Paxton Boys’ actions were examples of early American race wars, in which both sides saw themselves as inherently different from the other and believed the other needed to be eradicated. Pontiac’s War (1763-1766) triggered horrific violence on both sides. The War came to an end in 1766, when it became clear that the French, whom Pontiac had hoped would side with his forces, would not be returning. The repercussions, however, would last much longer. Race relations between Indians and whites remained poisoned on the frontier.

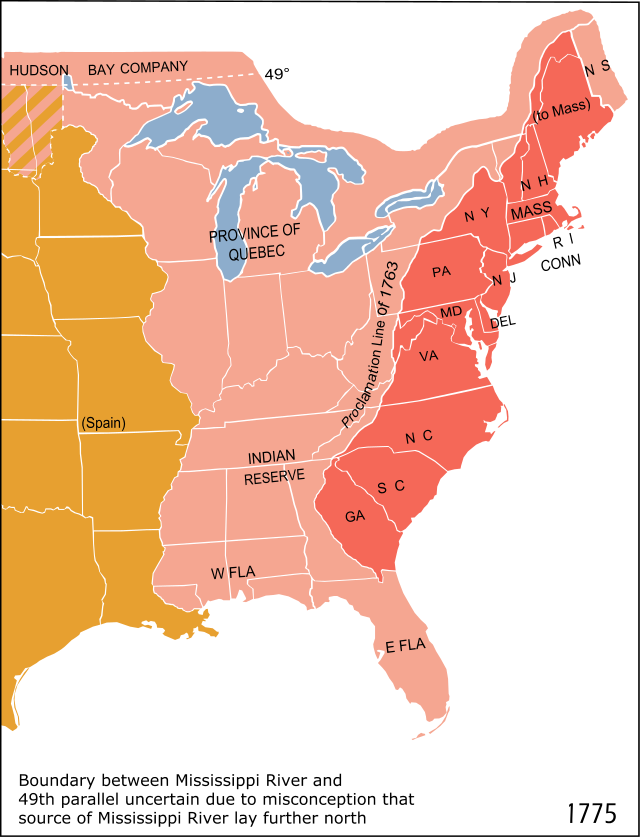

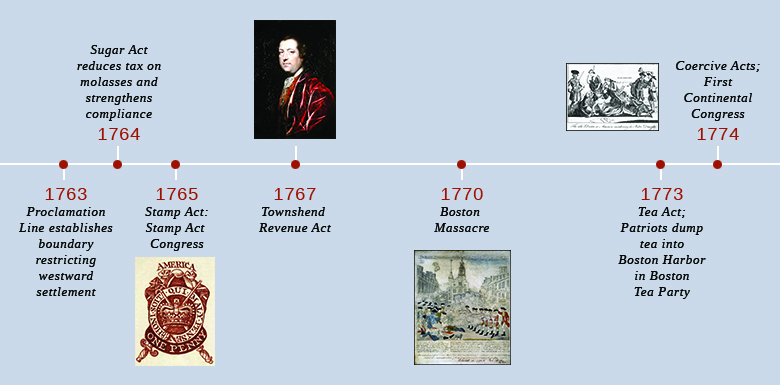

Well aware of the problems on the frontier, the British government took steps to try to prevent bloodshed and another costly war. At the beginning of Pontiac’s uprising, the British issued the Proclamation of 1763, which forbade white settlement west of the Proclamation Line, a borderline running along the spine of the Appalachian Mountains. The Proclamation Line aimed to forestall further conflict on the frontier, the clear flashpoint of tension in British North America. British colonists who had hoped to move west after the war chafed at this restriction, believing the war had been fought and won to ensure the right to settle west. The Proclamation Line therefore came as a setback to their vision of westward expansion.

This map shows the status of the American colonies in 1763, after the end of the French and Indian War. Although Great Britain won control of the territory east of the Mississippi, the Proclamation Line of 1763 prohibited British colonists from settling there. Source: Wikimedia Commons

THE BRITISH NATIONAL DEBT

Great Britain’s newly enlarged empire meant a greater financial burden, and the mushrooming debt from the war was a major cause of concern. The war nearly doubled the British national debt, from £75 million in 1756 to £133 million in 1763. The Empire needed more revenue to replenish its dwindling coffers. Those in Great Britain believed that British subjects in North America, as the major beneficiaries of Great Britain’s war for global supremacy, should certainly shoulder their share of the financial burden. Thus, the British government began increasing revenues by raising taxes at home and in the colonies.

IMPERIAL REFORMS

The new era of greater British interest in the American colonies through imperial reforms picked up in pace in the mid-1760s. In 1764, Prime Minister Grenville introduced the Currency Act of 1764, prohibiting the colonies from printing additional paper money and requiring colonists to pay British merchants in gold and silver instead of the colonial paper money already in circulation. The Currency Act aimed to standardize the currency used in Atlantic trade, a logical reform designed to help stabilize the Empire’s economy. This rule brought American economic activity under greater British control.

Grenville also pushed Parliament to pass the Sugar Act of 1764, which actually lowered duties on British molasses by half, from six pence per gallon to three. Grenville designed this measure to address the problem of rampant colonial smuggling with the French sugar islands in the West Indies. To give teeth to the 1764 Sugar Act, the law intensified enforcement provisions. The Sugar Act required violators to be tried in vice admiralty courts. These crown-sanctioned tribunals, which settled disputes that occurred at sea, operated without juries. Some colonists saw this feature of the 1764 act as dangerous. They argued that trial by jury had long been honored as a basic right of Englishmen under the British Constitution. To deprive defendants of a jury, they contended, meant reducing liberty-loving British subjects to political slavery.

As loyal British subjects, colonists in America cherished their Constitution, an unwritten system of government that they celebrated as the best political system in the world. The British Constitution prescribed the roles of the King, the House of Lords, and the House of Commons. Each entity provided a check and balance against the worst tendencies of the others. If the King had too much power, the result would be tyranny. If the Lords had too much power, the result would be oligarchy. If the Commons had the balance of power, democracy or mob rule would prevail. The British Constitution promised representation of the will of British subjects, and without such representation, even the indirect tax of the Sugar Act was considered a threat to the settlers’ rights as British subjects. All subjects of the British crown knew they had liberties under the constitution. The Sugar Act suggested that some in Parliament labored to deprive them of what made them uniquely British.

3.1 Section Summary

The British Empire gained supremacy in North America with its victory over the French in 1763. Almost all of the North American territory east of the Mississippi fell under Great Britain’s control, and British leaders took this opportunity to try to create a more coherent and unified empire after decades of lax oversight. Victory over the French had proved very costly, and the British government attempted to better regulate their expanded empire in North America. The initial steps the British took in 1763 and 1764 raised suspicions among some colonists about the intent of the home government. These suspicions would grow and swell over the coming years.

3.2 The Stamp Act and the Sons and Daughters of Liberty

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the purpose of the 1765 Stamp Act

- Describe the colonial responses to the Stamp Act

In 1765, the British Parliament moved beyond the efforts during the previous two years to better regulate westward expansion and trade by putting in place the Stamp Act. As a direct tax on the colonists, the Stamp Act imposed an internal tax on almost every type of printed paper colonists used, including newspapers, legal documents, and playing cards. While the architects of the Stamp Act saw the measure as a way to defray the costs of the British Empire, it nonetheless gave rise to the first major colonial protest against British imperial control as expressed in the famous slogan “no taxation without representation.” The Stamp Act reinforced the sense among some colonists that Parliament was not treating them as equals of their peers across the Atlantic.

THE STAMP ACT AND THE QUARTERING ACT

Prime Minister Grenville, author of the Sugar Act of 1764, introduced the Stamp Act in the early spring of 1765. Under this act, anyone who used or purchased anything printed on paper had to buy a revenue stamp for it. In the same year, 1765, Parliament also passed the Quartering Act, a law that attempted to solve the problems of stationing troops in North America. The Quartering Act of 1765 required that British troops be provided with barracks or places to stay in public houses, and that if extra housing were necessary, then troops could be stationed in barns and other uninhabited private buildings. In addition, the costs of the troops’ food and lodging fell to the colonists. Parliament understood the Stamp Act and the Quartering Act as an assertion of their power to control colonial policy.

The Stamp Act signaled a shift in British policy after the French and Indian War. Before the Stamp Act, the colonists had paid taxes to their colonial governments or indirectly through higher prices, not directly to the Crown’s appointed governors. This was a time-honored liberty of representative legislatures of the colonial governments. The passage of the Stamp Act meant that starting on November 1, 1765, the colonists would contribute £60,000 per year—17 percent of the total cost—to the upkeep of the ten thousand British soldiers in North America. Because the Stamp Act raised constitutional issues, it triggered the first serious protest against British imperial policy.

This painting shows a group of Bostonians burning a copy of the Stamp Act. Source: Wikimedia Commons

COLONIAL PROTEST: GENTRY, MERCHANTS, AND THE STAMP ACT CONGRESS

For many British colonists living in America, the Stamp Act raised many concerns. As a direct tax, it appeared to be an unconstitutional measure, one that deprived freeborn British subjects of their liberty, a concept they defined broadly to include various rights and privileges they enjoyed as British subjects, including the right to representation. With no representation in the House of Commons, where bills of taxation originated, they felt themselves deprived of this inherent right.

The British government knew the colonists might object to the Stamp Act’s expansion of parliamentary power, but Parliament believed the relationship of the colonies to the Empire was one of dependence, not equality. However, the Stamp Act had the unintended and ironic consequence of drawing colonists from very different areas and viewpoints together in protest. In Massachusetts, for instance, James Otis, a lawyer and defender of British liberty, became the leading voice for the idea that “Taxation without representation is tyranny.” In the Virginia House of Burgesses, firebrand and slaveholder Patrick Henry introduced the Virginia Stamp Act Resolutions, which denounced the Stamp Act and the British crown in language so strong that some conservative Virginians accused him of treason. Henry replied that Virginians were subject only to taxes that they themselves—or their representatives—imposed. In short, there could be no taxation without representation.

Patrick Henry Before the Virginia House of Burgesses (1851), painted by Peter F. Rothermel, offers a romanticized depiction of Henry’s speech denouncing the Stamp Act of 1765. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The colonists had never before formed a unified political front, so Grenville and Parliament did not fear true revolt. However, this was to change in 1765, when, in response to the Stamp Act, the Massachusetts Assembly sent letters to the other colonies, asking them to attend a meeting, or congress, to discuss how to respond to the act. Many American colonists from very different colonies found common cause in their opposition to the Stamp Act. Representatives from nine colonial legislatures met in New York in the fall of 1765 to reach a consensus. Could Parliament impose taxation without representation? The members of this first congress, known as the Stamp Act Congress, said no. These nine representatives had a vested interest in repealing the tax. Not only did it weaken their businesses and the colonial economy, but it also threatened their liberty under the British Constitution. They drafted a rebuttal to the Stamp Act, making clear that they desired only to protect their liberty as loyal subjects of the Crown. The document, called the Declaration of Rights and Grievances, outlined the unconstitutionality of taxation without representation and trials without juries. Meanwhile, popular protest was also gaining force.

MOBILIZATION: POPULAR PROTEST AGAINST THE STAMP ACT

The Stamp Act Congress in 1765 was a gathering of landowning, educated white men who represented the political elite of the colonies and was the colonial equivalent of the British landed aristocracy. While these gentry were drafting their grievances during the Stamp Act Congress, other colonists showed their distaste for the new act by boycotting British goods and protesting in the streets.

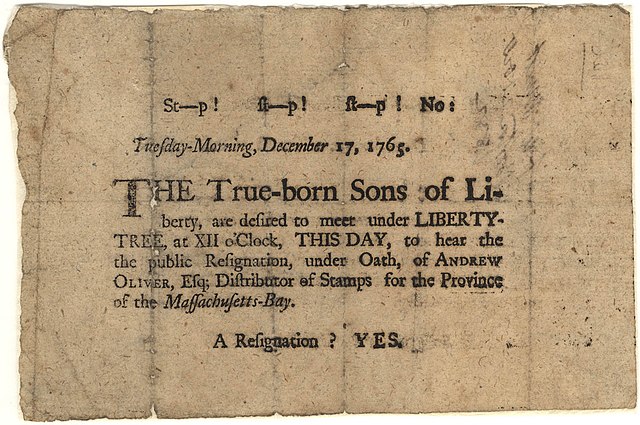

Two groups, the Sons of Liberty and the Daughters of Liberty, led the popular resistance to the Stamp Act. Both groups considered themselves British patriots defending their liberty. Forming in Boston in the summer of 1765, the Sons of Liberty were artisans, shopkeepers, and smalltime merchants willing to adopt extralegal means of protest. Before the act had even gone into effect, the Sons of Liberty began protesting. On August 14, they took aim at Andrew Oliver, who had been named the Massachusetts Distributor of Stamps. After hanging Oliver in effigy—that is, using a crudely made figure as a representation of Oliver—the unruly crowd stoned and ransacked his house, finally beheading the effigy and burning the remains. Such a brutal response shocked the royal governmental officials, who hid until the violence had spent itself. Andrew Oliver resigned the next day. By that time, the mob had moved on to the home of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson who, because of his support of Parliament’s actions, was considered an enemy of English liberty. The Sons of Liberty barricaded Hutchinson in his home and demanded that he renounce the Stamp Act; he refused, and the protesters looted and burned his house. Furthermore, the Sons (also called “True Sons” or “True-born Sons” to make clear their commitment to liberty and distinguish them from the likes of Hutchinson) continued to lead violent protests with the goal of securing the resignation of all appointed stamp collectors.

With this broadside of December 17, 1765, the Sons of Liberty (also called “True Sons” or “True-born Sons” to make clear their commitment to liberty) call for the resignation of Andrew Oliver, the Massachusetts Distributor of Stamps. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Starting in early 1766, the Daughters of Liberty protested the Stamp Act by refusing to buy British goods and encouraging others to do the same. They avoided British tea, opting to make their own teas with local herbs and berries. They built a community—and a movement—around creating homespun cloth instead of buying British linen. The Daughters’ non-importation movement broadened the protest against the Stamp Act, giving women a new and active role in the political dissent of the time. Although they could not vote, they could mobilize others and make a difference in the political landscape.

From a local movement, the protests of the Sons and Daughters of Liberty soon spread until there was a chapter in every colony. The Daughters of Liberty promoted the boycott on British goods while the Sons enforced it, threatening retaliation against anyone who bought imported goods or used stamped paper. At the same time, lawyers, printers, and merchants ran a propaganda campaign parallel to the Sons’ campaign of violence. In newspapers and pamphlets throughout the colonies, they published article after article outlining the reasons the Stamp Act was unconstitutional and urging peaceful protest.

|

|

AMERICANA |

|

“Address to the Ladies” Verse from The Boston Post-Boy and Advertiser This verse, which ran in a Boston newspaper in November 1767, highlights how women were encouraged to take political action by boycotting British goods. Notice that the writer especially encourages women to avoid British tea (Bohea and Green Hyson) and linen, and to manufacture their own homespun cloth. Building on the protest of the 1765 Stamp Act by the Daughters of Liberty, the nonimportation movement of 1767–1768 mobilized women as political actors.

Young ladies in town, and those that live round, Let a friend at this season advise you: Since money’s so scarce, and times growing worse Strange things may soon hap and surprize you: First then, throw aside your high top knots of pride Wear none but your own country linen: Of economy boast, let your pride be the most. What, if homespun they say is not quite so gay As brocades, yet be not in a passion, For when once it is known this is much wore in town, One and all will cry out, ’tis the fashion! And as one, all agree that you’ll not married be To such as will wear London Fact’ry: But at first sight refuse, tell’em such you do chuse As encourage our own Manufact’ry. No more Ribbons wear, nor in rich dress appear, Love your country much better than fine things, Begin without passion, ’twill soon be the fashion To grace your smooth locks with a twine string. Throw aside your Bohea, and your Green Hyson Tea, And all things with a new fashion duty; Procure a good store of the choice Labradore, For there’ll soon be enough here to suit ye; These do without fear and to all you’ll appear Fair, charming, true, lovely, and cleaver; Tho’ the times remain darkish, young men may be sparkish. And love you much stronger than ever. !O! |

|

THE DECLARATORY ACT

In Great Britain, news of the colonists’ reactions worsened an already volatile political situation. Grenville’s imperial reforms had brought about increased domestic taxes and his unpopularity led to his dismissal by King George III. While many in Parliament still wanted such reforms, British merchants argued strongly for their repeal. These merchants had no interest in the philosophy behind the colonists’ desire for liberty; rather, their motive was that the non-importation of British goods by North American colonists was hurting their business.

In March 1766, the new prime minister, Lord Rockingham, compelled Parliament to repeal the Stamp Act. Colonists celebrated what they saw as a victory for their British liberty. Colonists’ joy over the repeal of the Stamp Act and what they saw as their defense of liberty did not last long. To appease opponents of the repeal, who feared that it would weaken parliamentary power over the American colonists, Rockingham proposed the Declaratory Act. This stated in no uncertain terms that Parliament’s power was supreme and that any laws the colonies may have passed to govern and tax themselves were null and void if they ran counter to parliamentary law.

The Declaratory Act of 1766 articulated Great Britain’s supreme authority over the colonies, and Parliament soon began exercising that authority. In 1767, with the passage of the Townshend Acts, a tax on consumer goods in British North America, colonists believed their liberty as loyal British subjects had come under assault for a second time.

THE TOWNSHEND ACTS

Lord Rockingham’s tenure as prime minister was not long (1765–1766). Rich landowners feared that if he were not taxing the colonies, Parliament would raise their taxes instead, sacrificing them to the interests of merchants and colonists. George III duly dismissed Rockingham. William Pitt, also sympathetic to the colonists, succeeded him. However, Pitt was old and ill with gout. His chancellor of the exchequer, Charles Townshend, whose job was to manage the Empire’s finances, took on many of his duties. Primary among these was raising the needed revenue from the colonies.

The Townshend Revenue Act of 1767 placed duties on various consumer items like paper, paint, lead, tea, and glass. These British goods had to be imported, since the colonies did not have the manufacturing base to produce them. Townshend hoped the new duties would not anger the colonists because they were external taxes, not internal ones like the Stamp Act. However, like the Stamp Act, the Townshend Acts produced controversy and protest in the American colonies. For a second time, many colonists resented what they perceived as an effort to tax them without representation and thus to deprive them of their liberty.

Charles Townshend, chancellor of the exchequer, shown here in a 1765 painting by Joshua Reynolds, instituted the Townshend Revenue Act of 1767 in order to raise money to support the British military presence in the colonies. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Revenue Act also gave the customs board greater powers to counteract smuggling. It granted “writs of assistance”—basically, search warrants—to customs commissioners who suspected the presence of contraband goods, which also opened the door to a new level of bribery and trickery on the waterfronts of colonial America. Furthermore, to ensure compliance, Townshend introduced the Commissioners of Customs Act of 1767, which created an American Board of Customs to enforce trade laws. Customs enforcement had been based in Great Britain, but rules were difficult to implement at such a distance, and smuggling was rampant. The new customs board was based in Boston and would severely curtail smuggling in this large colonial seaport.

Townshend also orchestrated the Vice-Admiralty Court Act, which established three more vice-admiralty courts, in Boston, Philadelphia, and Charleston, to try violators of customs regulations without a jury. Before this, the only colonial vice-admiralty court had been in far-off Halifax, Nova Scotia, but with three local courts, smugglers could be tried more efficiently. Since the judges of these courts were paid a percentage of the worth of the goods they recovered, leniency was rare. All told, the Townshend Acts resulted in higher taxes and stronger British power to enforce them. Four years after the end of the French and Indian War, the Empire continued to search for solutions to its debt problem and the growing sense that the colonies needed to be brought under control.

The Townshend Acts generated a number of protest writings, including “Letters from a Pennsylvania Farmer” by John Dickinson. In this influential pamphlet, which circulated widely in the colonies, Dickinson conceded that the Empire could regulate trade but argued that Parliament could not impose either internal taxes, like stamps, on goods or external taxes, like customs duties, on imports.

In Massachusetts in 1768, Samuel Adams wrote a letter that became known as the Massachusetts Circular. Sent by the Massachusetts House of Representatives to the other colonial legislatures, the letter laid out the unconstitutionality of taxation without representation and encouraged the other colonies to again protest the taxes by boycotting British goods.

A pencil drawing of Samuel Adams by an unidentified artist. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Great Britain’s response to this threat of disobedience served only to unite the colonies further. The colonies’ initial response to the Massachusetts Circular was lukewarm at best. However, back in Great Britain, the secretary of state for the colonies—Lord Hillsborough—demanded that Massachusetts retract the letter, promising that any colonial assemblies that endorsed it would be dissolved. This threat had the effect of pushing the other colonies to Massachusetts’s side. Even the city of Philadelphia, which had originally opposed the Circular, came around to support it.

The Daughters of Liberty once again supported and promoted the boycott of British goods. Women resumed spinning bees and again found substitutes for British tea and other goods. Many colonial merchants signed non-importation agreements, and the Daughters of Liberty urged colonial women to shop only with those merchants. The Sons of Liberty used newspapers and circulars to call out by name those merchants who refused to sign such agreements; sometimes they were threatened by violence. The boycott in 1768–1769 turned the purchase of consumer goods into a political gesture. What you consumed mattered! Indeed, the very clothes you wore indicated whether you were a defender of liberty in homespun or a protector of parliamentary rights in superfine British attire.

TROUBLE IN BOSTON

The Massachusetts Circular got Parliament’s attention, and in 1768, Lord Hillsborough sent four thousand British troops to Boston to deal with the unrest and put down any potential rebellion there. The troops were a constant reminder of the assertion of British power over the colonies, an illustration of an unequal relationship between members of the same empire. Many Bostonians, led by the Sons of Liberty, mounted a campaign of harassment against British troops.

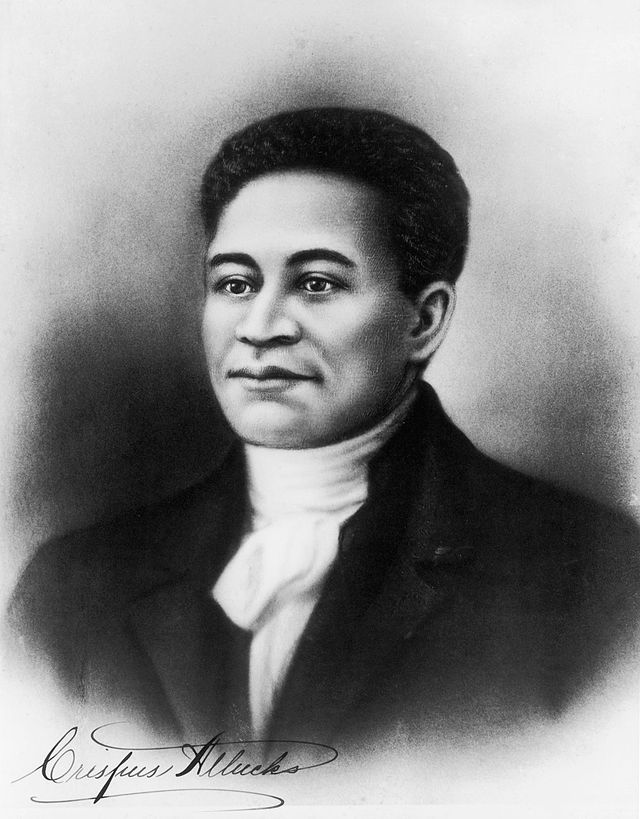

Conflict between the colonists and the British turned deadly on March 5, 1770, in a confrontation that came to be known as the Boston Massacre. On that night, a crowd of Bostonians from many walks of life started throwing snowballs, rocks, and sticks at the British soldiers guarding the customs house. In the resulting scuffle, some soldiers, goaded by the mob who hectored the soldiers as “lobster backs,”, fired into the crowd, killing five people. Crispus Attucks, the first man killed—and, though no one could have known it then, the first official casualty in the war for independence—was of Wampanoag and African descent. The bloodshed illustrated the level of hostility that had developed as a result of Boston’s occupation by British troops, the competition for scarce jobs between Bostonians and the British soldiers stationed in the city, and the larger question of Parliament’s efforts to tax the colonies.

A painting of Crispus Attucks by an unknown author (date unknown). Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Sons of Liberty immediately seized on the event, characterizing the British soldiers as murderers and their victims as martyrs. Paul Revere, a silversmith and member of the Sons of Liberty, circulated an engraving that showed a line of grim redcoats firing ruthlessly into a crowd of unarmed, fleeing civilians. Among colonists who resisted British power, this view of the “massacre” confirmed their fears of a tyrannous government using its armies to curb the freedom of British subjects.

PARTIAL REPEAL

As it turned out, the Boston Massacre occurred after Parliament had partially repealed the Townshend Acts. By the late 1760s, the American boycott of British goods had drastically reduced British trade. Once again, merchants who lost money because of the boycott strongly pressured Parliament to loosen its restrictions on the colonies and break the non-importation movement. Charles Townshend died suddenly in 1767 and was replaced by Lord North, who was inclined to look for a more workable solution with the colonists. North convinced Parliament to drop all the Townshend duties except the tax on tea.

To those who had protested the Townshend Acts for several years, the partial repeal appeared to be a major victory. For a second time, colonists had rescued liberty from an unconstitutional parliamentary measure. The hated British troops in Boston departed. The consumption of British goods skyrocketed after the partial repeal, an indication of the American colonists’ desire for the items linking them to the Empire.

|

|

AMERICANA |

|

Propaganda and the Sons of Liberty Long after the British soldiers had been tried and punished, the Sons of Liberty maintained a relentless propaganda campaign against British oppression. Many of them were printers or engravers, and they were able to use public media to sway others to their cause. Shortly after the incident outside the customs house, Paul Revere created “The bloody massacre perpetrated in King Street Boston on March 5th 1770 by a party of the 29th Regt.,” based on an image by engraver Henry Pelham. The picture—which represents only the protesters’ point of view—shows the ruthlessness of the British soldiers and the helplessness of the crowd of civilians. Notice the subtle details Revere uses to help convince the viewer of the civilians’ innocence and the soldiers’ cruelty. Although eyewitnesses said the crowd started the fight by throwing snowballs and rocks, in the engraving they are innocently standing by. Revere also depicts the crowd as well dressed and well-to-do, when in fact they were laborers and probably looked quite a bit rougher.

Newspaper articles and pamphlets that the Sons of Liberty circulated implied that the “massacre” was a planned murder. In the Boston Gazette on March 12, 1770, an article describes the soldiers as striking first. It goes on to discuss this version of the events: “On hearing the noise, one Samuel Atwood came up to see what was the matter; and entering the alley from dock square, heard the latter part of the combat; and when the boys had dispersed he met the ten or twelve soldiers aforesaid rushing down the alley towards the square and asked them if they intended to murder people? They answered Yes, by God, root and branch! With that one of them struck Mr. Atwood with a club which was repeated by another; and being unarmed, he turned to go off and received a wound on the left shoulder which reached the bone and gave him much pain.” |

|

3.2 Section Summary

Though Parliament designed the 1765 Stamp Act to deal with the financial crisis in the Empire, it had unintended consequences. Outrage over the act created a degree of unity among otherwise unconnected American colonists, giving them a chance to act together both politically and socially. The crisis of the Stamp Act allowed colonists to loudly proclaim their identity as defenders of British liberty. With the repeal of the Stamp Act in 1766, liberty-loving subjects of the king celebrated what they viewed as a victory. Like the Stamp Act in 1765, the Townshend Acts led many colonists to work together against what they perceived to be an unconstitutional measure, generating the second major crisis in British Colonial America. The experience of resisting the Townshend Acts provided another shared experience among colonists from diverse regions and backgrounds, while the partial repeal convinced many that liberty had once again been defended. Nonetheless, Great Britain’s debt crisis still had not been solved.

3.3 The Destruction of Tea and the Coercive Acts

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the socio-political environment in the colonies in the early 1770s

- Explain the purpose of the Tea Act of 1773 and discuss colonial reactions to it

- Identify and describe the Coercive Acts

The Tea Act of 1773 triggered a reaction with far more significant consequences than either the 1765 Stamp Act or the 1767 Townshend Acts. Colonists who had joined in protest against those earlier acts renewed their efforts in 1773. They understood that Parliament had again asserted its right to impose taxes without representation, and they feared the Tea Act was designed to seduce them into conceding this important principle by lowering the price of tea to the point that colonists might abandon their scruples. They also deeply resented the East India Company’s monopoly on the sale of tea in the American colonies; this resentment sprang from the knowledge that some members of Parliament had invested heavily in the company.

SMOLDERING RESENTMENT

Even after the partial repeal of the Townshend duties, however, suspicion of Parliament’s intentions remained high. This was especially true in port cities like Boston and New York, where British customs agents were a daily irritant and reminder of British power. In public houses and squares, people met and discussed politics. Philosopher John Locke’s Two Treatises of Government, published almost a century earlier, influenced political thought about the role of government to protect life, liberty, and property. The Sons of Liberty issued propaganda ensuring that colonists remained aware when Parliament overreached itself.

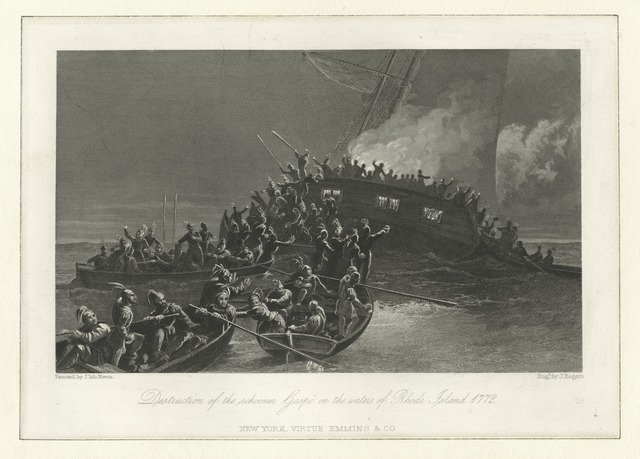

Violence continued to break out on occasion, as in 1772, when Rhode Island colonists boarded and burned the British revenue ship Gaspée in Narragansett Bay. Colonists had attacked or burned British customs ships in the past, but after the Gaspée Affair, the British government convened a Royal Commission of Inquiry. This Commission had the authority to remove the colonists, who were charged with treason, to Great Britain for trial. Some colonial protestors saw this new ability as another example of the overreach of British power.

This 1883 engraving, which appeared in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, depicts the burning of the British ship Gaspée by Rhode Island colonists. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Samuel Adams, along with Joseph Warren and James Otis, re-formed the Boston Committee of Correspondence, which functioned as a form of shadow government, to address the fear of British overreach. Soon towns all over Massachusetts had formed their own committees, and many other colonies followed suit. These committees, which had between seven and eight thousand members in all, identified enemies of the movement and communicated the news of the day. Sometimes they provided a version of events that differed from royal interpretations, and slowly, the committees began to supplant royal governments as sources of information. They later formed the backbone of communication among the colonies in the rebellion against the Tea Act, and eventually in the revolt against the British crown.

THE TEA ACT OF 1773

Parliament did not enact the Tea Act of 1773 in order to punish the colonists, assert parliamentary power, or even raise revenues. Rather, the act was a straightforward order of economic protectionism for a British tea firm, the East India Company, that was on the verge of bankruptcy. This act was not welcome to those in British North America who had grown displeased with the pattern of imperial measures. By granting a monopoly to the East India Company to sell tea in the colonies, the act not only cut out colonial merchants who would otherwise sell the tea themselves; it also reduced their profits from smuggled foreign tea. These merchants were among the most powerful and influential people in the colonies, so their dissatisfaction carried some weight. Moreover, because the tea tax that the Townshend Acts imposed remained in place, tea had intense power to symbolize the idea of “no taxation without representation.”

COLONIAL PROTEST: THE DESTRUCTION OF TEA

The 1773 Tea Act reignited the worst fears among the colonists. To the Sons and Daughters of Liberty and those who followed them, the act appeared to be proof that a handful of corrupt members of Parliament were violating the British Constitution. Veterans of the protest movement had grown accustomed to interpreting British actions in the worst possible light, so the 1773 act appeared to be part of a large conspiracy against liberty.

As they had done to protest earlier acts and taxes, colonists responded to the Tea Act with a boycott. The Committees of Correspondence helped to coordinate resistance in all of the colonial port cities, so up and down the East Coast, British tea-carrying ships were unable to come to shore and unload their wares.

In Boston, Thomas Hutchinson, now the royal governor of Massachusetts, vowed that radicals like Samuel Adams would not keep the ships from unloading their cargo. He urged the merchants who would have accepted the tea from the ships to stand their ground and receive the tea once it had been unloaded. When the Dartmouth sailed into Boston Harbor in November 1773, it had twenty days to unload its cargo of tea and pay the duty before it had to return to Great Britain. Two more ships, the Eleanor and the Beaver, followed soon after. Samuel Adams and the Sons of Liberty tried to keep the captains of the ships from paying the duties and posted groups around the ships to make sure the tea would not be unloaded.

On December 16, just as the Dartmouth’s deadline approached, townspeople gathered at the Old South Meeting House determined to take action. From this gathering, a group of Sons of Liberty and their followers approached the three ships. Some were disguised as Mohawks. Protected by a crowd of spectators, they systematically dumped all the tea into the harbor, destroying goods worth almost $1 million in today’s dollars, a very significant loss.

|

|

AMERICANA |

|

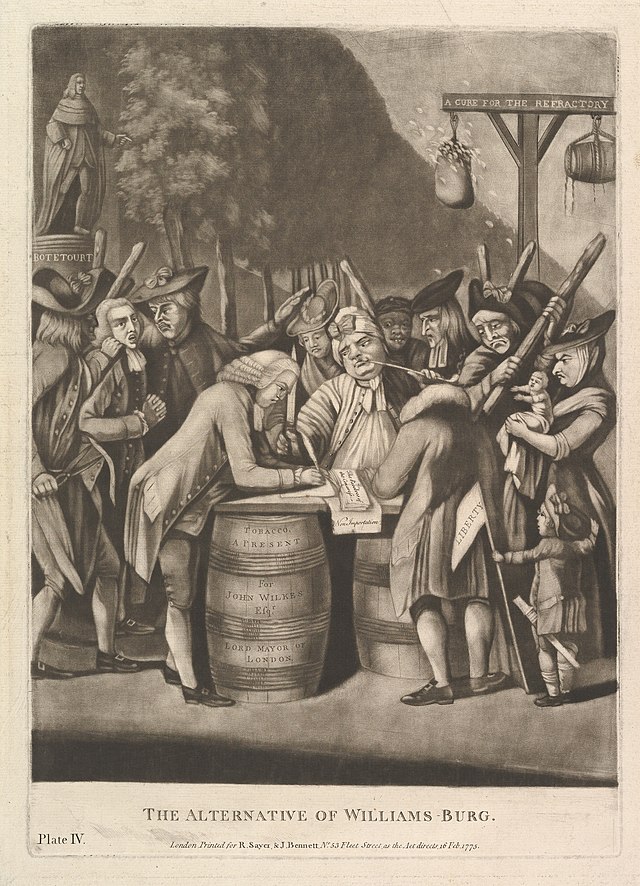

Joining the Boycott Many British colonists in Virginia, as in the other colonies, disapproved of the destruction of the tea in Boston Harbor. However, after the passage of the Coercive Acts, the Virginia House of Burgesses declared its solidarity with Massachusetts by encouraging Virginians to observe a day of fasting and prayer on May 24 in sympathy with the people of Boston. Almost immediately thereafter, Virginia’s colonial governor dissolved the House of Burgesses, but many of its members met again in secret on May 30 and adopted a resolution stating that “the Colony of Virginia will concur with the other Colonies in such Measures as shall be judged most effectual for the preservation of the Common Rights and Liberty of British America.” After the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, Virginia’s Committee of Safety ensured that all merchants signed the non-importation agreements that the Congress had proposed. In “The Alternative of Williams-Burg” (1775), a merchant has to sign a non-importation agreement or risk being covered with the tar and feathers suspended behind him. Note the tar and feathers hanging from the gallows in the background of this image and the demeanor of the people surrounding the signer.

|

|

PARLIAMENT RESPONDS: THE COERCIVE ACTS

In London, response to the destruction of the tea was swift and strong. The violent destruction of property infuriated King George III and the prime minister, Lord North, who insisted the loss be repaid. Though some American merchants put forward a proposal for restitution, the Massachusetts Assembly refused to make payments. Massachusetts’s resistance to British authority united different factions in Great Britain against the colonies. Both Parliament and the king agreed that Massachusetts should be forced to both pay for the tea and yield to British authority.

In early 1774, leaders in Parliament responded with a set of four measures designed to punish Massachusetts, commonly known at the Coercive Acts. The Boston Port Act shut down Boston Harbor until the East India Company was repaid. The Massachusetts Government Act placed the colonial government under the direct control of crown officials and made traditional town meetings subject to the governor’s approval. The Administration of Justice Act allowed the royal governor to unilaterally move any trial of a crown officer out of Massachusetts, a change designed to prevent hostile Massachusetts juries from deciding these cases. This act was especially infuriating to colonists who emphasized the time-honored rule of law. They saw this part of the Coercive Acts as striking at the heart of fair and equitable justice.

American Patriots renamed these Acts the Intolerable Acts. Some in London also thought the acts went too far; see the cartoon “The Able Doctor, or America Swallowing the Bitter Draught” for one British view of what Parliament was doing to the colonies. Meanwhile, punishments designed to hurt only one colony (Massachusetts, in this case) had the effect of mobilizing all the colonies to its side. The Committees of Correspondence had already been active in coordinating an approach to the Tea Act. Now the talk would turn to these new, intolerable assaults on the colonists’ rights as British subjects.

This 18th century English political cartoon shows Lord North, with the “Boston Port Bill” extending from a pocket, forcing tea (the Intolerable Acts) down the throat of a partially draped Native female figure representing “America” whose arms. Source: Wikimedia Commons

3.3 Section Summary

The colonial rejection of the Tea Act, especially the destruction of the tea in Boston Harbor, recast the decade-long argument between British colonists and the home government as an intolerable conspiracy against liberty and an excessive overreach of parliamentary power. The Coercive Acts were punitive in nature, awakening the worst fears of otherwise loyal members of the British Empire in America.

3.4 Disaffection: The First Continental Congress, and American Identity

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the state of affairs between the colonies and the home government in 1774

- Explain the purpose and results of the First Continental Congress

Disaffection—the loss of affection toward the home government—had reached new levels by 1774. Many colonists viewed the Intolerable Acts as a turning point; they now felt they had to take action. The result was the First Continental Congress, a direct challenge to Lord North and British authority in the colonies.

After the passage of the Intolerable Acts in 1774, the Committees of Correspondence and the Sons of Liberty went straight to work, spreading warnings about how the acts would affect the liberty of all colonists, not just urban merchants and laborers. The Massachusetts Government Act had shut down the colonial government there, but resistance-minded colonists began meeting in extralegal assemblies. One of these assemblies, the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, passed the Suffolk Resolves in September 1774, which laid out a plan of resistance to the Intolerable Acts. Meanwhile, the First Continental Congress was convening to discuss how to respond to the acts themselves.

The First Continental Congress was made up of elected representatives of twelve of the thirteen American colonies. (Georgia’s royal governor blocked the move to send representatives from that colony, an indication of the continued strength of the royal government despite the crisis.) The representatives met in Philadelphia from September 5 through October 26, 1774. In the Declaration and Resolves, adopted on October 14, the colonists demanded the repeal of all repressive acts passed since 1773 and agreed to a non-importation, non-exportation, and non-consumption pact against all British goods until the acts were repealed.

|

|

DEFINING “AMERICAN” |

|

The First List of Un-American Activities In her book Toward A More Perfect Union: Virtue and the Formation of American Republics, historian Ann Fairfax Withington explores actions the delegates to the First Continental Congress took during the weeks they were together. Along with their efforts to bring about the repeal of the Intolerable Acts, the delegates also banned certain activities they believed would undermine their fight against what they saw as British corruption. In particular, the delegates prohibited horse races, cockfights, the theater, and elaborate funerals. The reasons for these prohibitions provide insight into the state of affairs in 1774. Both horse races and cockfights encouraged gambling. For the delegates, gambling threatened to prevent the unity of action and purpose they desired. In addition, cockfighting (as depicted in The Cockpit drawing by British engraver William Hogarth in 1759) appeared immoral and corrupt because the roosters were fitted with razors and fought to the death.

The ban on the theater aimed to do away with another corrupt British practice. Critics had long believed that theatrical performances drained money from working people. Moreover, they argued, theatergoers learned to lie and deceive from what they saw on stage. The delegates felt banning the theater would demonstrate their resolve to act honestly and without pretense in their fight against corruption. Finally, eighteenth-century mourning practices often required lavish spending on luxury items and even the employment of professional mourners who, for a price, would shed tears at the grave. Prohibiting these practices reflected the idea that luxury bred corruption, and the First Continental Congress wanted to demonstrate that the colonists would do without British vices. Congress emphasized the need to be frugal and self-sufficient when confronted with corruption. The First Continental Congress banned all four activities—horse races, cockfights, the theater, and elaborate funerals—and entrusted the Continental Association with enforcement. Rejecting what they saw as corruption coming from Great Britain, the delegates were also identifying themselves as standing apart from their British relatives. They cast themselves as virtuous defenders of liberty against a corrupt Parliament. |

|

The representatives at the First Continental Congress created a Continental Association to ensure that the full boycott was enforced across all the colonies. The Continental Association served as an umbrella group for colonial and local committees of observation and inspection. By taking these steps, the First Continental Congress established a governing network in opposition to royal authority.

In the Declaration and Resolves and the Petition of Congress to the King, the delegates to the First Continental Congress refer to George III as “Most Gracious Sovereign” and to themselves as “inhabitants of the English colonies in North America” or “inhabitants of British America,” indicating that they still considered themselves British subjects of the king, not American citizens. At the same time, however, they were slowly moving away from British authority, creating their own de facto government in the First Continental Congress. As a sign that the Congress was becoming an elected government, one of the provisions of the Congress was that it meet again in one year to mark its progress; .

3.4 Section Summary

The First Continental Congress, which comprised elected representatives from twelve of the thirteen American colonies, represented a direct challenge to British authority. In its Declaration and Resolves, colonists demanded the repeal of all repressive acts passed since 1773. The delegates also recommended that the colonies raise militias, lest the British respond to the Congress’s proposed boycott of British goods with force. While the colonists still considered themselves British subjects, they were slowly retreating from British authority, creating their own de facto government via the First Continental Congress.

3.5 Britain’s Law-and-Order Strategy and Its Consequences

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the beginnings of the American Revolution

Great Britain pursued a policy of law and order when dealing with the crises in the colonies in the late 1760s and 1770s. Relations between the British and many American Patriots worsened over the decade, culminating in an unruly mob destroying a fortune in tea by dumping it into Boston Harbor in December 1773 as a protest against British tax laws. The harsh British response to this act in 1774, which included sending British troops to Boston and closing Boston Harbor, caused tensions and resentments to escalate further. The British tried to disarm the insurgents in Massachusetts by confiscating their weapons and ammunition and arresting the leaders of the patriotic movement. However, this effort faltered on April 19, when Massachusetts militias and British troops fired on each other as British troops marched to Lexington and Concord, an event immortalized by poet Ralph Waldo Emerson as the “shot heard round the world.” The American Revolution had begun.

In an effort to restore law and order in Boston, the British dispatched General Thomas Gage to the New England seaport. He arrived in Boston in May 1774 as the new royal governor of the Province of Massachusetts, accompanied by several regiments of British troops. As in 1768, the British again occupied the town. Both the British and the rebels in New England began to prepare for conflict by turning their attention to supplies of weapons and gunpowder. General Gage stationed thirty-five hundred troops in Boston, and from there he ordered periodic raids on towns where guns and gunpowder were stockpiled, hoping to impose law and order by seizing them. As Boston became the headquarters of British military operations, many residents fled the city.

Gage’s actions led to the formation of local rebel militias that were able to mobilize in a minute’s time. These minutemen, many of whom were veterans of the French and Indian War, played an important role in the war for independence. In one instance, General Gage seized munitions in Cambridge and Charlestown, but when he arrived to do the same in Salem, his troops were met by a large crowd of minutemen and had to leave empty-handed. In New Hampshire, minutemen took over Fort William and Mary and confiscated weapons and cannons there. New England readied for war.

THE OUTBREAK OF FIGHTING

Throughout late 1774 and into 1775, tensions in New England continued to mount. General Gage knew that a powder magazine was stored in Concord, Massachusetts, and on April 19, 1775, he ordered troops to seize these munitions. Instructions from London called for the arrest of rebel leaders Samuel Adams and John Hancock. Hoping for secrecy, his troops left Boston under cover of darkness, but riders from Boston let the militias know of the British plans. Minutemen met the British troops and skirmished with them, first at Lexington and then at Concord. The British retreated to Boston, enduring ambushes from several other militias along the way. Over four thousand militiamen took part in these skirmishes with British soldiers. Seventy-three British soldiers and forty-nine Patriots died during the British retreat to Boston. The famous confrontation is the basis for Emerson’s “Concord Hymn” (1836), which begins with the description of the “shot heard round the world.”

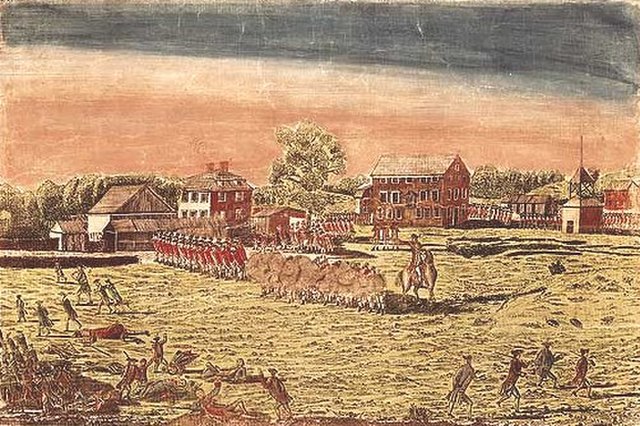

Amos Doolittle was an American printmaker who volunteered to fight against the British. His engravings of the battles of Lexington and Concord—such as this detail from The Battle of Lexington, April 19th 1775—are the only contemporary American visual records of the event.

After the battles of Lexington and Concord, New England fully mobilized for war. Thousands of militias from towns throughout New England marched to Boston, and soon the city was besieged by a sea of rebel forces. In May 1775, Ethan Allen and Colonel Benedict Arnold led a group of rebels against Fort Ticonderoga in New York. They succeeded in capturing the fort, and cannons from Ticonderoga were brought to Massachusetts and used to bolster the Siege of Boston.

In June, General Gage resolved to take Breed’s Hill and Bunker Hill, the high ground across the Charles River from Boston, a strategic site that gave the rebel militias an advantage since they could train their cannons on the British. In the Battle of Bunker Hill, on June 17, the British launched three assaults on the hills, gaining control only after the rebels ran out of ammunition. British losses were very high—over two hundred were killed and eight hundred wounded—and, despite his victory, General Gage was unable to break the colonial forces’ siege of the city.

In August, King George III declared the colonies to be in a state of rebellion. Parliament and many in Great Britain agreed with their king. Meanwhile, the British forces in Boston found themselves in a terrible predicament, isolated in the city and with no control over the countryside.

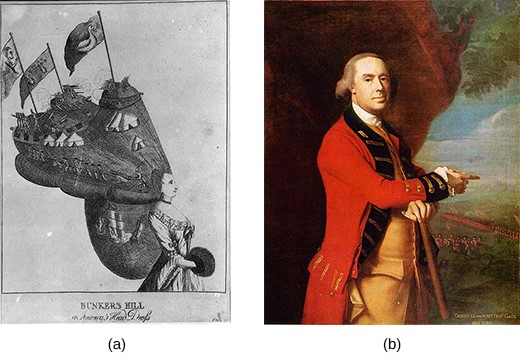

The British cartoon “Bunkers Hill or America’s Head Dress” (a) depicts the initial rebellion as an elaborate colonial coiffure. The illustration pokes fun at both the colonial rebellion and the overdone hairstyles for women that had made their way from France and Britain to the American colonies. Despite gaining control of the high ground after the colonial militias ran out of ammunition, General Thomas Gage (b), shown here in a painting made in 1768–1769 by John Singleton Copley, was unable to break the siege of the city. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In the end, General George Washington, commander in chief of the Continental Army since June 15, 1775, used the Fort Ticonderoga cannons to force the evacuation of the British from Boston. Washington had positioned these cannons on the hills overlooking both the fortified positions of the British and Boston Harbor, where the British supply ships were anchored. The British could not return fire on the colonial positions because they could not elevate their cannons. They soon realized that they were in an untenable position and had to withdraw from Boston. On March 17, 1776, the British evacuated their troops to Halifax, Nova Scotia, ending the nearly year-long siege.

By the time the British withdrew from Boston, fighting had broken out in other colonies as well. In May 1775, Mecklenburg County in North Carolina issued the Mecklenburg Resolves, stating that a rebellion against Great Britain had begun, that colonists did not owe any further allegiance to Great Britain, and that governing authority had now passed to the Continental Congress. The resolves also called upon the formation of militias to be under the control of the Continental Congress. Loyalists and Patriots clashed in North Carolina in February 1776 at the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge.

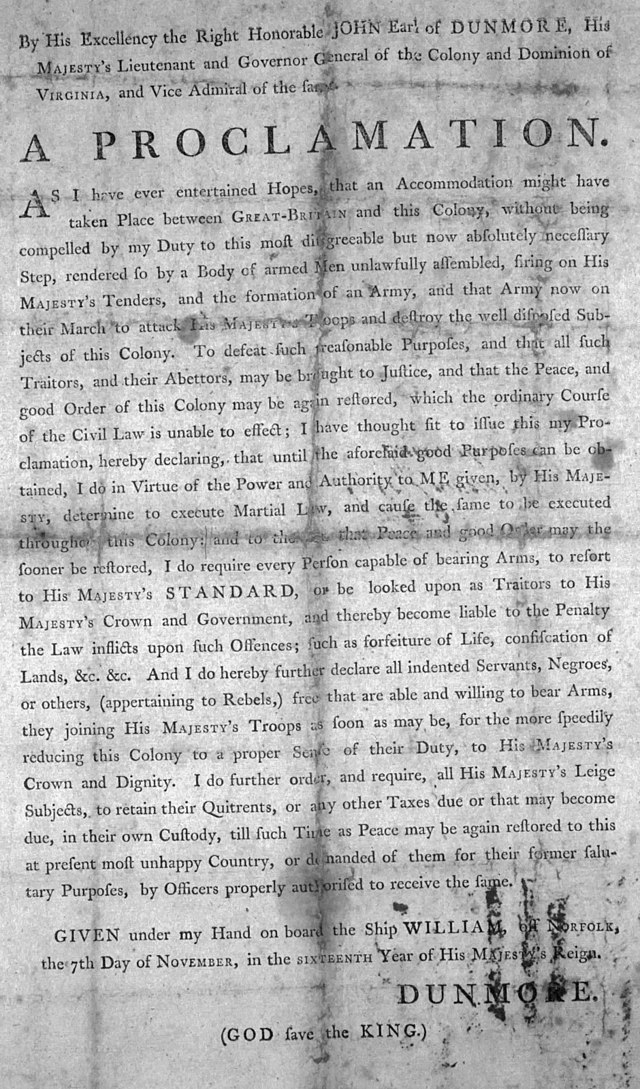

In Virginia, the royal governor, Lord Dunmore, raised Loyalist forces to combat the rebel colonists and also tried to use the large slave population to put down the rebellion. In November 1775, he issued a decree, known as Dunmore’s Proclamation, promising freedom to slaves and indentured servants of rebels who remained loyal to the king and who pledged to fight with the Loyalists against the insurgents. Dunmore’s Proclamation exposed serious problems for both the Patriot cause and for the British. In order for the British to put down the rebellion, they needed the support of Virginia’s landowners, many of whom owned slaves. Although a number of enslaved people did join Dunmore’s side, the proclamation had the unintended effect of galvanizing Patriot resistance to Britain. From the rebels’ point of view, the British looked to deprive them of their slave property and incite a race war. Slaveholders feared a slave uprising and increased their commitment to the cause against Great Britain, calling for independence. Dunmore fled Virginia in 1776.

A copy of Dunmore’s Proclamation, issued November 7, 1775. Source: Wikimedia Commons

COMMON SENSE

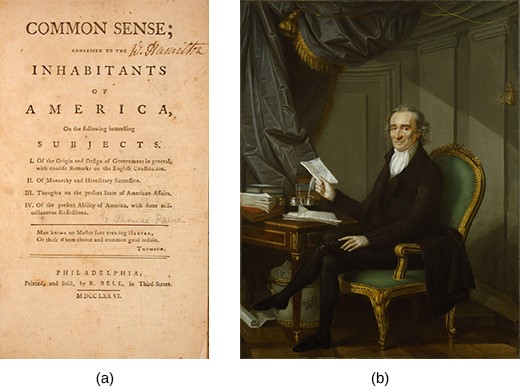

With the events of 1775 fresh in their minds, many colonists reached the conclusion in 1776 that the time had come to secede from the Empire and declare independence. Over the past ten years, these colonists had argued that they deserved the same rights as Englishmen enjoyed in Great Britain, only to find themselves relegated to an intolerable subservient status in the Empire. The groundswell of support for their cause of independence in 1776 also owed much to the appearance of an anonymous pamphlet, first published in January 1776, entitled Common Sense.

Thomas Paine, who had emigrated from England to Philadelphia in 1774, was the author. Arguably the most radical pamphlet of the revolutionary era, Common Sense made a powerful argument for independence. Paine wrote Common Sense in simple, direct language aimed at ordinary people, not just the learned elite. The pamphlet proved immensely popular and was soon available in all thirteen colonies, where it helped convince many to reject monarchy and the British Empire in favor of independence and a republican form of government.

Thomas Paine’s Common Sense (a) helped convince many colonists of the need for independence from Great Britain. Paine is shown here in a portrait by Laurent Dabos (b). Source: Wikimedia Commons

THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE

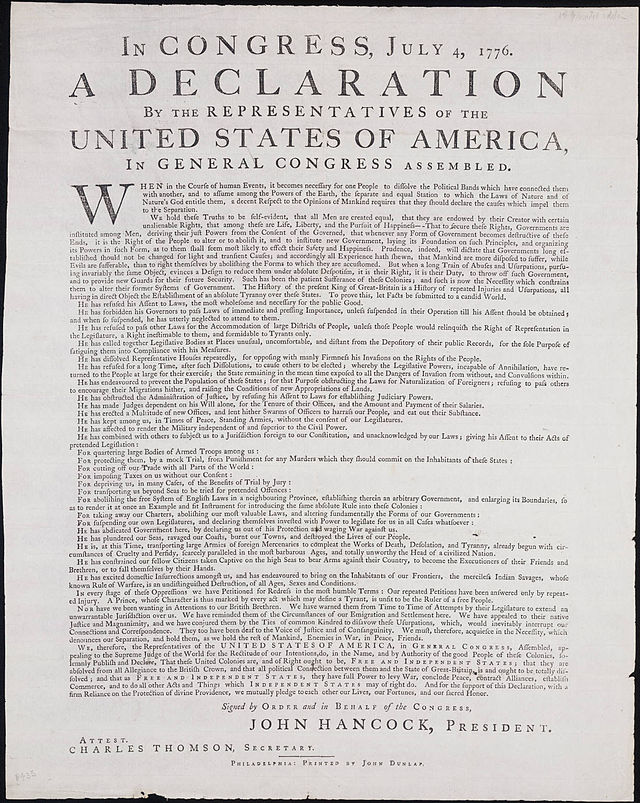

In the summer of 1776, the Continental Congress met in Philadelphia and agreed to sever ties with Great Britain. Virginian Thomas Jefferson and John Adams of Massachusetts, with the support of the Congress, articulated the justification for liberty in the Declaration of Independence. The Declaration, written primarily by Jefferson, included a long list of grievances against King George III and laid out the foundation of American government as a republic in which the consent of the governed would be of paramount importance.

The preamble to the Declaration began with a statement of Enlightenment principles about universal human rights and values: “We hold these Truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness—That to secure these Rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed, that whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or abolish it.” In addition to this statement of principles, the document served another purpose: Patriot leaders sent copies to France and Spain in hopes of winning their support and aid in the contest against Great Britain. They understood how important foreign recognition and aid would be to the creation of a new and independent nation.

When delegates to the Second Continental Congress approved the Declaration in July 1776, they were not only severing ties with Great Britain—they were also making a bold argument about the nature of government and human rights. This document became a touchstone of American political thought and has continued to shape debates about freedom, equality, and power ever since.

As you read, consider the following: What specific grievances are listed against King George III? How does the document define the role and purpose of government? What ideas about human rights and political authority does it assume? In what ways does its language reflect Enlightenment thinking? And how might its claims have been received differently by enslaved people, women, or Indigenous nations?

Read the Declaration of Independence.

The Declaration also reveals a fundamental contradiction of the American Revolution: the conflict between the existence of slavery and the idea that “all men are created equal.” One-fifth of the population in 1776 was enslaved, and at the time he drafted the Declaration, Jefferson himself owned more than one hundred slaves. Further, the Declaration framed equality as existing only among white men; women and nonwhites were entirely left out of a document that referred to native peoples as “merciless Indian savages” who indiscriminately killed men, women, and children. Nonetheless, the promise of equality for all planted the seeds for future struggles waged by enslaved people, women, and many others to bring about its full realization. Much of American history is the story of the slow realization of the promise of equality expressed in the Declaration of Independence.

The Dunlap Broadsides, one of which is shown here, are considered the first published copies of the Declaration of Independence. This one was printed on July 4, 1776. Source: Wikimedia Commons

3.5 Section Summary

Until Parliament passed the Coercive Acts in 1774, most colonists still thought of themselves as proud subjects of the strong British Empire. However, the Coercive (or Intolerable) Acts, which Parliament enacted to punish Massachusetts for failing to pay for the destruction of the tea, convinced many colonists that Great Britain was indeed threatening to stifle their liberty. In Massachusetts and other New England colonies, militias like the minutemen prepared for war by stockpiling weapons and ammunition. After the first loss of life at the battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, skirmishes continued throughout the colonies. When Congress met in Philadelphia in July 1776, its members signed the Declaration of Independence, officially breaking ties with Great Britain and declaring their intention to be self-governing.

3.6 The Revolution

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the British and American military strategies of 1776 through 1778

- Understand the reasons for the American success in the Revolutionary War

After the British evacuated from Boston, they slowly adopted a strategy to isolate New England from the rest of the colonies and force the insurgents in that region into submission, believing that doing so would end the conflict. At first, British forces focused on taking the principal colonial centers. They began by easily capturing New York City in 1776. The following year, they took over the American capital of Philadelphia. The larger British effort to isolate New England was implemented in 1777. That effort ultimately failed when the British surrendered a force of over five thousand to the Americans in the fall of 1777 at the Battle of Saratoga.

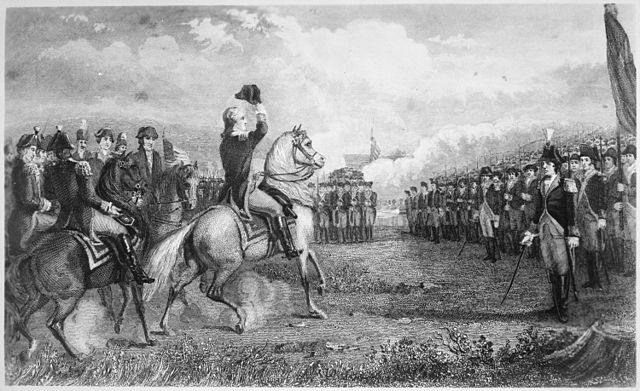

GEORGE WASHINGTON AND THE CONTINENTAL ARMY

When the Second Continental Congress met in Philadelphia in May 1775, members approved the creation of a professional Continental Army with Washington as commander in chief. Although sixteen thousand volunteers enlisted, it took several years for the Continental Army to become a truly professional force. In 1775 and 1776, militias still composed the bulk of the Patriots’ armed forces, and these soldiers returned home after the summer fighting season, drastically reducing the army’s strength.

This 1775 etching shows George Washington taking command of the Continental Army at Cambridge, Massachusetts, just two weeks after his appointment by the Continental Congress. Source: Wikimedia Commons

That changed in late 1776 and early 1777, when Washington broke with conventional eighteenth-century military tactics that called for fighting in the summer months only. Intent on raising revolutionary morale after the British captured New York City, he launched surprise strikes against British forces in their winter quarters. In Trenton, New Jersey, he led his soldiers across the Delaware River and surprised an encampment of Hessians, German mercenaries hired by Great Britain to put down the American rebellion. Beginning the night of December 25, 1776, and continuing into the early hours of December 26, Washington moved on Trenton where the Hessians were encamped. Maintaining the element of surprise by attacking at Christmastime, he defeated them, taking over nine hundred soldiers captive. On January 3, 1777, Washington achieved another much-needed victory at the Battle of Princeton. He again broke with eighteenth-century military protocol by attacking unexpectedly after the fighting season had ended.

VALLEY FORGE AND FRENCH SUPPORT

In August 1777, General Howe brought fifteen thousand British troops to Chesapeake Bay as part of his plan to take Philadelphia, where the Continental Congress met. That fall, the British defeated Washington’s soldiers in the Battle of Brandywine Creek and took control of Philadelphia, forcing the Continental Congress to flee. During the winter of 1777–1778, the British occupied the city, and Washington’s army camped at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania.

Washington’s winter at Valley Forge was a low point for the American forces. A lack of supplies weakened the men, and disease took a heavy toll. Amid the cold, hunger, and sickness, soldiers deserted in droves. The low morale extended all the way to Congress, where some wanted to replace Washington with a more seasoned leader.

Assistance came to Washington and his soldiers in February 1778 in the form of the Prussian soldier Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben. Baron von Steuben was an experienced military man, and he implemented a thorough training course for Washington’s ragtag troops. By drilling a small corps of soldiers and then having them train others, he finally transformed the Continental Army into a force capable of standing up to the professional British and Hessian soldiers.

Prussian soldier Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, shown here in a 1786 portrait by Ralph Earl, was instrumental in transforming Washington’s Continental Army into a professional armed force. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The growing professionalism of the American War and a key victory against the British at Saratoga (New York) helped to convince the French to recognize American independence and form a military alliance with the new nation. Still smarting from their defeat by Britain in the Seven Years’ War, the French supplied the United States with gunpowder and money, as well as soldiers and naval forces that proved decisive in the defeat of Great Britain. The French also contributed military leaders, including the Marquis de Lafayette, who arrived in America in 1777 as a volunteer and served as Washington’s aide-de-camp.

The war quickly became more difficult for the British, who had to fight the rebels in North America as well as the French in the Caribbean. Following France’s lead, Spain joined the war against Great Britain in 1779, though it did not recognize American independence until 1783. The Dutch Republic also began to support the American revolutionaries and signed a treaty of commerce with the United States in 1782.

YORKTOWN