9 Chapter 9: Politics in the Gilded Age: Populists and Progressives, 1870-1919

Politics in the Gilded Age: Populists and Progressives, 1870-1919

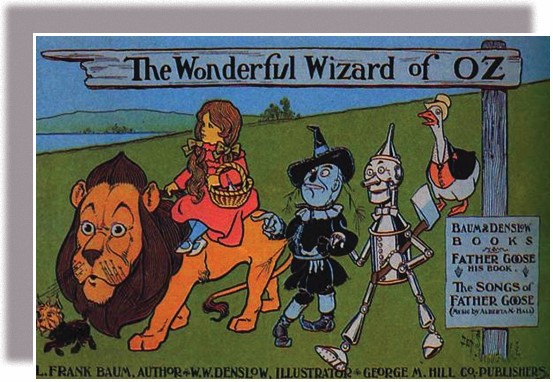

L. Frank Baum’s story of a Kansas girl and the magical land of Oz has become a classic of both film and screen, but it may have originated in part as an allegory of late nineteenth-century politics and the rise of the Populist movement. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Chapter Outline

Introduction,, Watch and Learn,, Questions to Guide your Reading

9.1 Political Corruption in Postbellum America

9.2 Farmers Revolt in the Populist Era

9.3 Social and Labor Unrest in the 1890s

9.4 The Progressive Spirit in America

9.5 New Voices for Women and African Americans

9.6 Progressivism in the White House

9.7 The United States Prepares for War

9.8 A New Home Front

Summary Timelines, Chapter 9 Self-Test, Chapter 9 Key Term Crossword Puzzle

Introduction

L. Frank Baum was a journalist who rose to prominence at the end of the nineteenth century. Baum’s most famous story, The Wizard of Oz, was published in 1900, but “Oz” first came into being years earlier, when he told a story to a group of schoolchildren visiting his newspaper office in South Dakota. He made up a tale of a wonderful land, and, searching for a name, he allegedly glanced down at his file cabinet, where the bottom drawer was labeled “O-Z.” Thus was born the world of Oz, where a girl from struggling Kansas hoped to get help from a “wonderful wizard” who proved to be a fraud. Since then, many have speculated that the story reflected Baum’s political sympathies for the Populist Party, which galvanized midwestern and southern farmers’ demands for federal reform. Whether he intended the story to act as an allegory for the plight of farmers and workers in late nineteenth-century America, or whether he simply wanted to write an “American fairy tale” set in the heartland, Populists looked for answers much like Dorothy did. And the government in Washington proved to be meek rather than magical.

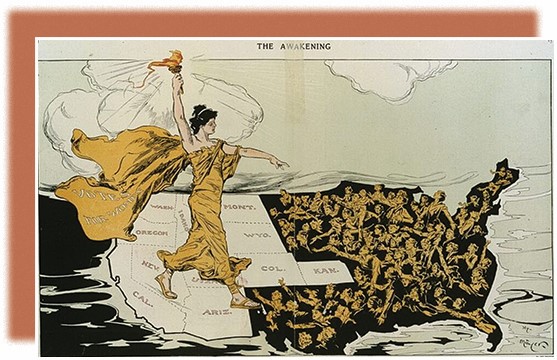

Women’s suffrage was one of many causes that emerged at this time, as Americans confronted the numerous challenges of the late nineteenth century. Starting in the late 1800s, women increasingly were working outside the home—a task almost always done for money, not empowerment—as well as pursuing higher education, both at universities that were beginning to allow women to enroll and at female-only schools. Often, it was educated middle-class women with more time and resources that took up causes such as child labor and family health. As more women led new organizations or institutions, such as the settlement houses, they grew to have a greater voice on issues of social change. By the turn of the century, a strong movement had formed to advocate for a woman’s right to vote. For three decades, suffragist groups pushed for legislation to give women the right to vote in every state. As the illustration to the left demonstrates, the western states were the first to grant women the right to vote; it would not be until 1920 that the nation would extend that right to all women.

The western states were the first to allow women the right to vote, a freedom that grew out of the less deeply entrenched gendered spheres in the region. This illustration, from 1915, shows a suffragist holding a torch over the western states and inviting the beckoning women from the rest of the country to join her. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Watch and Learn (Crash Course in History videos for chapter 9)

- The Gilded Age

- The Progressive Era

- Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois

- Women’s Suffrage

- Progressive Presidents

- America in World War 1

Questions to Guide Your Reading

- How does the term “Gilded Age” characterize American society in the late nineteenth century? In what ways is this characterization accurate or inaccurate?

- Did the Populist Party make a wise decision in choosing to support the Democratic Party’s candidate in the 1896 presidential election? Why or why not?

- Explain the fundamental differences between Roosevelt’s “New Nationalism” and Wilson’s “New Freedom.”

- Describe the multiple groups and leaders that emerged in the fight for the Progressive agenda, including women’s rights, African American rights, and workers’ rights. How were the philosophies, agendas, strategies, and approaches of these leaders and organizations similar and different? What made it difficult for all Progressive activists to present a united front?

- How did President Theodore Roosevelt’s “Square Deal” epitomize the notion that the federal government should serve as a steward protecting the public’s interests?

- How did the goals and reform agenda of the Progressive Era manifest themselves during the presidential administrations of Roosevelt, Taft, and Wilson?

- What vestiges of Progressivism can we see in our modern lives—politically, economically, and socially? Which of our present-day political processes, laws, institutions, and attitudes have roots in this era? Why have they had such staying power?

- What changes did the war bring to the everyday lives of Americans? How lasting were these changes?

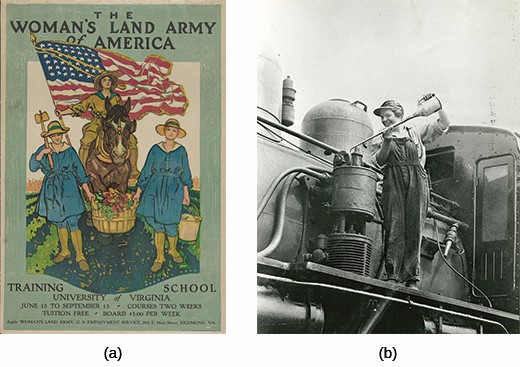

- What new opportunities did the war present for women and African Americans? What limitations did these groups continue to face in spite of these opportunities?

9.1 Political Corruption in Postbellum America

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the national political scene during the Gilded Age

- Analyze why many critics considered the Gilded Age a period of ineffective national leadership

The challenges Americans faced in the post-Civil War era extended far beyond the issue of Reconstruction and the challenge of an economy without slavery. Political and social repair of the nation was paramount, as was the correlative question of race relations in the wake of slavery. In addition, farmers faced the task of cultivating arid western soils and selling crops in an increasingly global commodities market, while workers in urban industries suffered long hours and hazardous conditions at stagnant wages.

Farmers, who still composed the largest percentage of the U.S. population, faced mounting debts as agricultural prices spiraled downward. These lower prices were due in large part to the cultivation of more acreage using more productive farming tools and machinery, global market competition, as well as price manipulation by commodity traders, exorbitant railroad freight rates, and costly loans upon which farmers depended. For many, their hard work resulted merely in a continuing decline in prices and even greater debt. These farmers, and others who sought leaders to heal the wounds left from the Civil War, organized in different states, and eventually into a national third-party challenge, only to find that, with the end of Reconstruction, federal political power was stuck in a permanent partisan stalemate, and corruption was widespread at both the state and federal levels.

As the Gilded Age unfolded, presidents had very little power, due in large part to highly contested elections in which relative popular majorities were razor thin. Two presidents won the Electoral College without a popular majority. Further undermining their efficacy was a Congress comprising mostly politicians operating on the principle of political patronage. Eventually, frustrated by the lack of leadership in Washington, some Americans began to develop their own solutions, including the establishment of new political parties and organizations to directly address the problems they faced. Out of the frustration wrought by war and presidential political impotence, as well as an overwhelming pace of industrial change, farmers and workers formed a new grassroots reform movement that, at the end of the century, was eclipsed by an even larger, mostly middle-class, Progressive movement. These reform efforts did bring about change—but not without a fight.

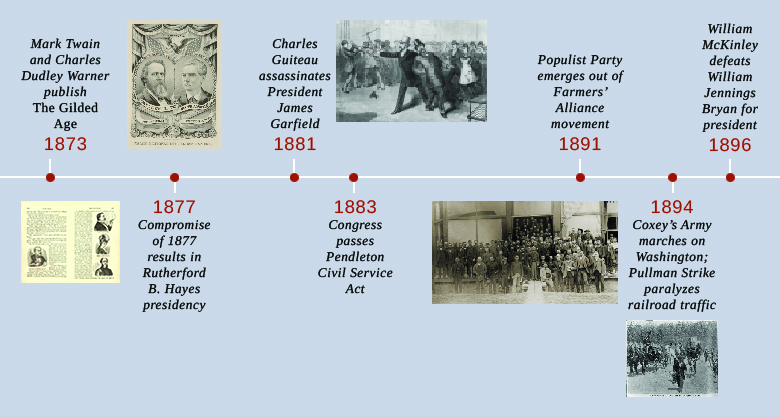

THE GILDED AGE

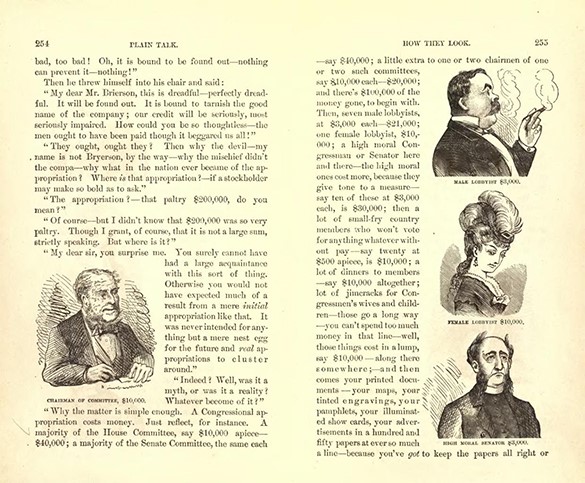

Mark Twain coined the phrase “Gilded Age” in a book he co-authored with Charles Dudley Warner in 1873, The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. The book satirized the corruption of post-Civil War society and politics. Indeed, popular excitement over national growth and industrialization only thinly glossed over the stark economic inequalities and various degrees of corruption of the era. Politicians of the time largely catered to business interests in exchange for political support and wealth. Many participated in graft and bribery, often justifying their actions with the excuse that corruption was too widespread for a successful politician to resist. The machine politics of the cities, specifically Tammany Hall in New York, illustrate the kind of corrupt, but effective, local and national politics that dominated the era.

Pages from Mark Twain’s The Gilded Age, published in 1873. The illustrations in this chapter reveal the cost of doing business in Washington in this new age of materialism and corruption, with the cost of obtaining a female lobbyist’s support set at $10,000, while that of a male lobbyist or a “high moral” senator can be had for $3,000. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Nationally, between 1872 and 1896, the lack of clear popular mandates made presidents reluctant to venture beyond the interests of their traditional supporters. As a result, for nearly a quarter of a century, presidents had a weak hold on power, and legislators were reluctant to tie their political agendas to such weak leaders. On the contrary, weakened presidents were more susceptible to support various legislators’ and lobbyists’ agendas, as they owed tremendous favors to their political parties, as well as to key financial contributors, who helped them garner just enough votes to squeak into office through the Electoral College. As a result of this relationship, the rare pieces of legislation passed were largely responses to the desires of businessmen and industrialists whose support helped build politicians’ careers.

|

|

DEFINING “AMERICAN” |

|

Mark Twain and the Gilded Age Mark Twain (see image below) wrote The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today with his neighbor, Charles Dudley Warner, as a satire about the corrupt politics and lust for power that he felt characterized American society at the time. The book, the only novel Twain ever co-authored, tells of the characters’ desire to sell their land to the federal government and become rich. It takes aim at both the government in Washington and those Americans, in the South and elsewhere, whose lust for money and status among the newly rich in the nation’s capital leads them to corrupt and foolish choices.

In the following conversation from Chapter Fifty-One of the book, Colonel Sellers instructs young Washington Hawkins on the routine practices of Congress: “Now let’s figure up a little on, the preliminaries. I think Congress always tries to do as near right as it can, according to its lights. A man can’t ask any fairer than that. The first preliminary it always starts out on, is to clean itself, so to speak. It will arraign two or three dozen of its members, or maybe four or five dozen, for taking bribes to vote for this and that and the other bill last winter.” “It goes up into the dozens, does it?” “Well, yes; in a free country likes ours, where any man can run for Congress and anybody can vote for him, you can’t expect immortal purity all the time—it ain’t in nature. Sixty or eighty or a hundred and fifty people are bound to get in who are not angels in disguise, as young Hicks the correspondent says; but still it is a very good average; very good indeed. . . . Well, after they have finished the bribery cases, they will take up cases of members who have bought their seats with money. That will take another four weeks.” “Very good; go on. You have accounted for two-thirds of the session.” “Next they will try each other for various smaller irregularities, like the sale of appointments to West Point cadetships, and that sort of thing— . . . ” “How long does it take to disinfect itself of these minor impurities?” “Well, about two weeks, generally.” “So Congress always lies helpless in quarantine ten weeks of a session. That’s encouraging.” |

|

What was the result of this political malaise? Not surprisingly, almost nothing was accomplished on the federal level. However, problems associated with the tremendous economic growth during this time continued to mount. More Americans were moving to urban centers, which were unable to accommodate the massive numbers of working poor. Tenement houses with inadequate sanitation led to widespread illness. In rural parts of the country, people fared no better. Farmers were unable to cope with the challenges of low prices for their crops and exorbitant costs for everyday goods. All around the country, Americans in need of solutions turned further away from the federal government for help, leading to the rise of fractured and corrupt political groups.

THE ELECTION OF 1876 SETS THE TONE

The election of Rutherford Hayes in 1876 set the stage for politically motivated agendas and widespread inefficiency in the White House for the next twenty-four years. Weak president after weak president took office, and, as mentioned above, not one incumbent was reelected. The populace, it seemed, preferred the devil they didn’t know to the one they did. Once elected, presidents had barely enough power to repay the political favors they owed to the individuals who ensured their narrow victories in cities and regions around the country. Their four years in office were spent repaying favors and managing the powerful relationships that put them in the White House. Everyday Americans were largely left on their own. Among the few political issues that presidents routinely addressed during this era were ones of patronage, tariffs, and the nation’s monetary system.

As can be seen in the table below, every single president elected from 1876 through 1892 won despite receiving less than 50 percent of the popular vote. This established a repetitive cycle of relatively weak presidents who owed many political favors, which could be repaid through one prerogative power: patronage. As a result, the spoils system allowed those with political influence to ascend to powerful positions within the government, regardless of their level of experience or skill, thus compounding both the inefficiency of government as well as enhancing the opportunities for corruption.

|

U.S. Presidential Election Results (1876–1896) |

|

|||

|

Year |

Candidates |

Popular Vote |

Percentage |

Electoral Vote |

|

1876 |

Rutherford B. Hayes |

4,034,132 |

47.9% |

185 |

|

|

Samuel Tilden |

4,286,808 |

50.9% |

184 |

|

|

Others |

97,709 |

1.2% |

0 |

|

1880 |

James Garfield |

4,453,337 |

48.3% |

214 |

|

|

Winfield Hancock |

4,444,267 |

48.2% |

155 |

|

|

Others |

319,806 |

3.5% |

0 |

|

1884 |

Grover Cleveland |

4,914,482 |

48.8% |

219 |

|

|

James Blaine |

4,856,903 |

48.3% |

182 |

|

|

Others |

288,660 |

2.9% |

0 |

|

1888 |

Benjamin Harrison |

5,443,663 |

47.8% |

233 |

|

|

Grover Cleveland |

5,538,163 |

48.6% |

168 |

|

|

Others |

407,050 |

3.6% |

0 |

|

1892 |

Grover Cleveland |

5,553,898 |

46.0% |

277 |

|

|

Benjamin Harrison |

5,190,799 |

43.0% |

145 |

|

|

Others |

1,323,330 |

11.0% |

22 |

|

1896 |

William McKinley |

7,112,138 |

51.0% |

271 |

|

|

William Jennings Bryan |

6,510,807 |

46.7% |

176 |

|

|

Others |

315,729 |

2.3% |

0 |

MONETARY POLICIES AND THE ISSUE OF GOLD VS SILVER

Although political corruption, the spoils system, and the question of tariff rates were popular discussions of the day, none were more relevant to working-class Americans and farmers than the issue of the nation’s monetary policy and the ongoing debate of gold versus silver. There had been frequent attempts to establish a bimetallic standard, which in turn would have created inflationary pressures and placed more money into circulation that could have subsequently benefitted farmers. But the government remained committed to the gold standard, including the official demonetizing of silver altogether in 1873. Such a stance greatly benefitted prominent businessmen engaged in foreign trade while forcing more farmers and working-class Americans into greater debt.

As farmers and working-class Americans sought the means by which to pay their bills and other living expenses, especially in the wake of increased tariffs as the century came to a close, many saw adherence to a strict gold standard as their most pressing problem. With limited gold reserves, the money supply remained constrained. The lack of meaningful monetary measures from the federal government would lead one group in particular who required such assistance—American farmers—to attempt to take control over the political process itself.

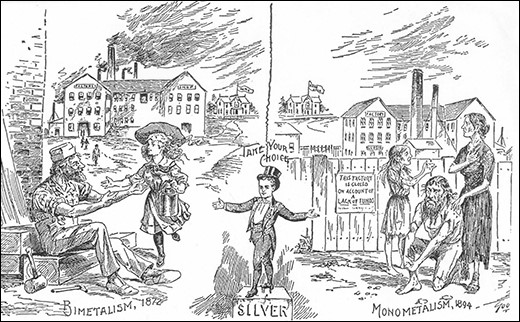

This cartoon illustrates the potential benefits of a bimetal system, but the benefits did not actually extend to big business, which preferred the gold standard and worked to keep it. Source: Wikimedia Commons

9.1 Section Summary

In the years following the Civil War, American politics were disjointed, corrupt, and, at the federal level, largely ineffective in terms of addressing the challenges that Americans faced. Local and regional politics, and the bosses who ran the political machines, dominated through systematic graft and bribery. Americans around the country recognized that solutions to the mounting problems they faced would not come from Washington, DC, but from their local political leaders. Thus, the cycle of federal ineffectiveness and machine politics continued through the remainder of the century relatively unabated. Meanwhile, in the Compromise of 1877, an electoral commission declared Rutherford B. Hayes the winner of the contested presidential election in exchange for the withdrawal of federal troops from South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida. As a result, Southern Democrats were able to reestablish control over their home governments, which would have a tremendous impact on the direction of southern politics and society in the decades to come. All told, from 1872 through 1892, Gilded Age politics were little more than political showmanship. The political issues of the day, including the spoils system versus civil service reform, high tariffs versus low, and business regulation, all influenced politicians more than the country at large. Very few measures offered direct assistance to Americans who continued to struggle with the transformation into an industrial society.

9.2 Farmers Revolt in the Populist Era

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand how the economic and political climate of the day promoted the formation of the farmers’ protest movement in the latter half of the nineteenth century

- Explain how the farmers’ revolt moved from protest to politics

The challenges that many American farmers faced in the last quarter of the nineteenth century were significant. They contended with economic hardships born out of rapidly declining farm prices, prohibitively high tariffs on items they needed to purchase, and foreign competition. One of the largest challenges they faced was overproduction, where the glut of their products in the marketplace drove the price lower and lower.

Overproduction of crops occurred in part due to the westward expansion of homestead farms and in part because industrialization led to new farm tools that dramatically increased crop yields. As farmers fell deeper into debt, whether it be to the local stores where they bought supplies or to the railroads that shipped their produce, their response was to increase crop production each year in the hope of earning more money with which to pay back their debt. The more they produced, the lower prices dropped. To a hard-working farmer, the notion that their own overproduction was the greatest contributing factor to their debt was a completely foreign concept.

In addition to the cycle of overproduction, tariffs were a serious problem for farmers. Rising tariffs on industrial products made purchased items more expensive, yet tariffs were not being used to keep farm prices artificially high as well. Therefore, farmers were paying inflated prices but not receiving them. Finally, the issue of gold versus silver as the basis of U.S. currency was a very real problem to many farmers. Farmers needed more money in circulation, whether it was paper or silver, in order to create inflationary pressure. Inflationary pressure would allow farm prices to increase, thus allowing them to earn more money that they could then spend on the higher-priced goods in stores. In short, farmers had a big stack of bills and wanted a big stack of money—be it paper or silver—to pay them. Neither was forthcoming from a government that cared more about issues of patronage and how to stay in the White House for more than four years at a time.

This North Dakota sod hut, built by a homesteading farmer for his family, was photographed in 1898, two years after it was built. While the country was quickly industrializing, many farmers still lived in rough, rural conditions. Source: Wikimedia Commons

FARMERS BEGIN TO ORGANIZE

The initial response by increasingly frustrated and angry farmers was to organize into groups that were similar to early labor unions. Taking note of how the industrial labor movement had unfolded in the last quarter of the century, farmers began to understand that a collective voice could create significant pressure among political leaders and produce substantive change. While farmers had their own challenges, including that of geography and diverse needs among different types of famers, they believed this model to be useful to their cause.

One of the first efforts to organize farmers came in 1867 with Oliver Hudson Kelly’s creation of the Patrons of Husbandry, more popularly known as the Grange. In the wake of the Civil War, the Grangers quickly grew to over 1.5 million members in less than a decade. Kelly believed that farmers could best help themselves by creating farmers’ cooperatives in which they could pool resources and obtain better shipping rates, as well as prices on seeds, fertilizer, machinery, and other necessary inputs. These cooperatives, he believed, would let them self-regulate production as well as collectively obtain better rates from railroad companies and other businesses.

This print from the early 1870s, with scenes of farm life, was a promotional poster for the Grangers, one of the earliest farmer reform groups. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Farmers’ Alliance, a conglomeration of three regional alliances formed in the mid-1880s, took root in the wake of the Grange movement. In 1890, Dr. Charles Macune, who led the Southern Alliance, which was based in Texas and had over 100,000 members by 1886, urged the creation of a national alliance between his organization, the Northwest Alliance, and the Colored Alliance, the largest African American organization in the United States. Led by Tom Watson, the Colored Alliance, which was founded in Texas but quickly spread throughout the Old South, counted over one million members. Although they originally advocated for self-help, African Americans in the group soon understood the benefits of political organization and a unified voice to improve their plight, regardless of race. While racism kept the alliance splintered among the three component branches, they still managed to craft a national agenda that appealed to their large membership. All told, the Farmers’ Alliance brought together over 2.5 million members, 1.5 million white and 1 million black.

The Farmers’ Alliance flag displays the motto: “The most good for the most PEOPLE,” clearly a sentiment they hoped that others would believe. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The alliance movement, and the subsequent political party that emerged from it, also featured prominent roles for women. Nearly 250,000 women joined the movement due to their shared interest in the farmers’ worsening situation as well as the promise of being a full partner with political rights within the group, which they saw as an important step towards advocacy for women’s suffrage on a national level. The ability to vote and stand for office within the organization encouraged many women who sought similar rights on the larger American political scene. Prominent alliance spokeswoman, Mary Elizabeth Lease of Kansas, often spoke of membership in the Farmers’ Alliance as an opportunity to “raise less corn and more hell!”

FROM ORGANIZATION TO POLITICAL PARTY

Angry at the federal government’s continued unwillingness to substantively address the plight of the average farmer, Charles Macune and the Farmers’ Alliance chose to create a political party whose representatives—if elected—could enact real change. Put simply, if the government would not address the problem, then it was time to change those elected to power.

In 1891, the alliance formed the Populist Party, or People’s Party, as it was more widely known. At their national convention in1892 in Omaha, Nebraska, they wrote the Omaha Platform to more fully explain to all Americans the goals of the new party. Written by Ignatius Donnelly, the statement vilified railroad owners, bankers, and big businessmen as all being part of a widespread conspiracy to control farmers. As for policy changes, the platform called for adoption of the subtreasury plan, government control over railroads, an end to the national bank system, the creation of a federal income tax, the direct election of U.S. senators, and several other measures, all of which aimed at a more proactive federal government that would support the economic and social welfare of all Americans.

The People’s Party gathered for its nominating convention in Nebraska, where they wrote the Omaha Platform to state their concerns and goals. Source: Wikimedia Commons

9.2 Section Summary

Factors such as overproduction and high tariffs left the country’s farmers in increasingly desperate straits, and the federal government’s inability to address their concerns left them disillusioned and worried. Uneven responses from state governments had many farmers seeking an alternative solution to their problems. Taking note of the labor movements growing in industrial cities around the country, farmers began to organize into alliances similar to workers’ unions; these were models of cooperation where larger numbers could offer more bargaining power with major players such as railroads. Ultimately, the alliances were unable to initiate widespread change for their benefit. Still, drawing from the cohesion of purpose, farmers sought to create change from the inside: through politics. They hoped the creation of the Populist Party in 1891 would lead to a president who put the people—and in particular the farmers—first.

9.3 Social and Labor Unrest in the 1890s

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how the Depression of 1893 helped the Populist Party to grow in popularity in the 1890s

- Understand the forces that contributed to the Populist Party’s decline following the 1896 presidential election

Insofar as farmers wanted the rest of the country to share their plight, they got their wish. In 1893, the nation catapulted into the worst economic depression in its history to date. As the government continued to fail in its efforts to address the growing problems, more and more Americans sought relief outside of the traditional two-party system. To many industrial workers, the Populist Party began to seem like a viable solution.

FROM FARMERS’ HARDSHIPS TO A NATIONAL DEPRESSION

The late 1880s and early 1890s saw the American economy slide precipitously. The causes of the Depression of 1893 were manifold, but one major element was the speculation in railroads over the previous decades. The rapid proliferation of railroad lines created a false impression of growth for the economy as a whole. Banks and investors fed the growth of the railroads with fast-paced investment in industry and related businesses, not realizing that the growth they were following was built on a bubble. When the railroads began to fail due to expenses outpacing returns on their construction, the supporting businesses, from banks to steel mills, failed also.

In a single year, from 1893 to 1894, unemployment estimates increased from 3 percent to nearly 19 percent of all working-class Americans. In some states, the unemployment rate soared even higher: over 35 percent in New York State and 43 percent in Michigan. At the height of this depression, over three million American workers were unemployed. By 1895, Americans living in cities grew accustomed to seeing the homeless on the streets or lining up at soup kitchens.

Immediately following the economic downturn, people sought relief through their elected federal government. Just as quickly, they learned what farmers had been taught in the preceding decades: A weak, inefficient government interested solely in patronage and the spoils system in order to maintain its power was in no position to help the American people face this challenge. The federal government had little in place to support those looking for work or to provide direct aid to those in need.

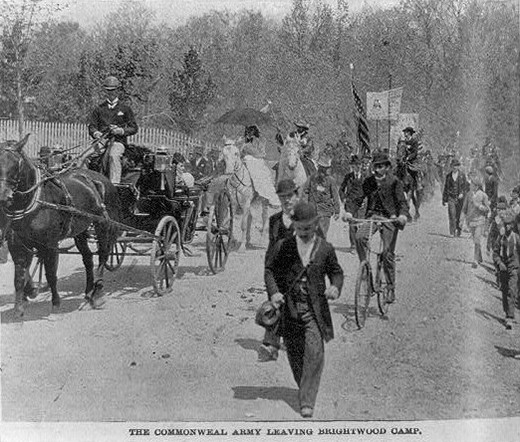

A notable example of the government’s failure to act was the story of Coxey’s Army. In the spring of 1894, businessman Jacob Coxey led a march of unemployed Ohioans from Cincinnati to Washington, DC, where leaders of the group urged Congress to pass public works legislation for the federal government to hire unemployed workers to build roads and other public projects. From the original one hundred protesters, the march grew to over five hundred as others joined along the route to the nation’s capital. Upon their arrival, not only were their cries for federal relief ignored, but Coxey and several other marchers were arrested for trespassing on the grass outside the U.S. Capitol. Frustration over the event led many angry workers to consider supporting the Populist Party in subsequent elections.

This image of Coxey’s Army marching on Washington to ask for jobs may have helped inspire L. Frank Baum’s story of Dorothy and her friends seeking help from the Wizard of Oz. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Several strikes also punctuated the growing depression, including a number of violent uprisings in the coal regions of Ohio and Pennsylvania. But the infamous Pullman Strike of 1894 was most notable for its nationwide impact, as it all but shut down the nation’s railroad system in the middle of the depression. Thus, the Depression of 1893 left the country limping towards the next presidential election with few solutions in sight.

|

|

AMERICANA |

|

L. Frank Baum: Did Coxey’s Army inspire Dorothy and the Wizard of Oz? Scholars, historians, and economists have long argued inconclusively that L. Frank Baum intended the story of The Wizard of Oz as an allegory for the politics of the day. Whether that actually was Baum’s intention is up for debate, but certainly the story could be read as support for the Populist Party’s crusade on behalf of American farmers. In 1894, Baum witnessed Coxey’s Army’s march firsthand, and some feel it may have influenced the story. According to this theory, the Scarecrow represents the American farmer, the Tin Woodman is the industrial worker, and the Cowardly Lion is William Jennings Bryan, a prominent “Silverite” (strong supporters of the Populist Party who advocated for the free coinage of silver) who, in 1900 when the book was published, was largely criticized by the Republicans as being cowardly and indecisive. In the story, the characters march towards Oz, much as Coxey’s Army marched to Washington. Like Dorothy and her companions, Coxey’s Army gets in trouble, before being turned away with no help. Following this reading, the seemingly powerful but ultimately impotent Wizard of Oz is a representation of the president, and Dorothy only finds happiness by wearing the silver slippers—they only became ruby slippers in the later movie version—along the Yellow Brick Road, a reference to the need for the country to move from the gold standard to a two-metal silver and gold plan. While no literary theorists or historians have proven this connection to be true, it is possible that Coxey’s Army inspired Baum to create Dorothy’s journey on the yellow brick road. |

|

THE ELECTION OF 1896

As the final presidential election of the nineteenth century unfolded, all signs pointed to a possible Populist victory. Not only had the ongoing economic depression convinced many Americans—farmers and factory workers alike—of the inability of either major political party to address the situation, but also the Populist Party, since the last election, benefited from four more years of experience and numerous local victories. As they prepared for their convention in St. Louis that summer, the Populists watched with keen interest as the Republicans and Democrats hosted their own conventions.

The Republicans remained steadfast in their defense of a gold-based standard for the American economy, as well as high protective tariffs. They turned to William McKinley, former congressman and current governor of Ohio, as their candidate. At their convention, the Democrats turned to William Jennings Bryan—a congressman from Nebraska. Bryan defended the importance of a silver-based monetary system and urged the government to coin more silver. Furthermore, being from farm country, he was very familiar with the farmers’ plight. In short, Bryan could have been the ideal Populist candidate, but the Democrats got to him first. The Populist Party subsequently endorsed Bryan as well, with their party’s nomination three weeks later.

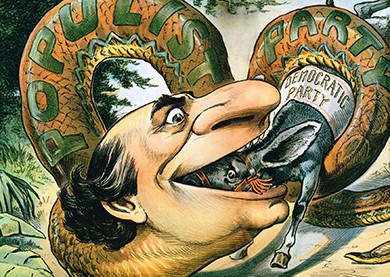

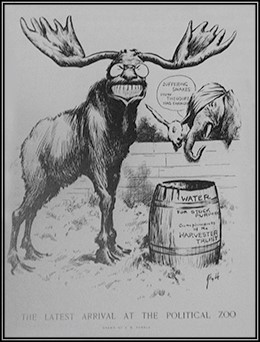

Republicans portrayed presidential candidate Bryan as a grasping politician whose Populist leanings could swallow the Democratic Party. Bryan was in fact not a Populist at all, but a Democrat whose views aligned with the Populists on some issues. He was formally nominated by the Democratic Party, the Populist Party, and the Silver Republican Party for the 1896 presidential election. Source: Wikimedia Commons

|

|

DEFINING “AMERICAN” |

|

William Jennings Bryan and the “Cross of Gold” William Jennings Bryan was a politician and speechmaker in the late nineteenth century, and he was particularly well known for his impassioned argument that the country move to a bimetal or silver standard. He received the Democratic presidential nomination in 1896, and, at the nominating convention, he gave his most famous speech. He sought to argue against Republicans who stated that the gold standard was the only way to ensure stability and prosperity for American businesses. In the speech he said: We say to you that you have made the definition of a business man too limited in its application. The man who is employed for wages is as much a business man as his employer; the attorney in a country town is as much a business man as the corporation counsel in a great metropolis; the merchant at the cross-roads store is as much a business man as the merchant of New York; the farmer who goes forth in the morning and toils all day, who begins in spring and toils all summer, and who by the application of brain and muscle to the natural resources of the country creates wealth, is as much a business man as the man who goes upon the Board of Trade and bets upon the price of grain; . . . We come to speak of this broader class of businessmen. This defense of working Americans as critical to the prosperity of the country resonated with his listeners, as did his passionate ending when he stated, “Having behind us the producing masses of this nation and the world, supported by the commercial interests, the laboring interests, and the toilers everywhere, we will answer their demand for a gold standard by saying to them: ‘You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns; you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.’” The speech was an enormous success and played a role in convincing the Populist Party that he was the candidate for them. |

|

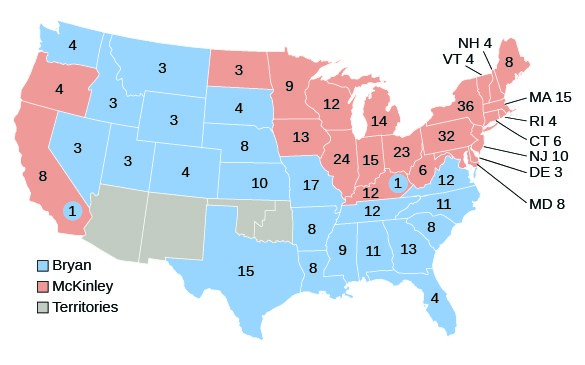

The result was a close election that finally saw a U.S. president win a majority of the popular vote for the first time in twenty-four years. McKinley defeated Bryan by a popular vote of 7.1 million to 6.5 million. Bryan’s showing was impressive by any standard, as his popular vote total exceeded that of any other presidential candidate in American history to that date—winner or loser. However, his campaign also served to split the Democratic vote, as some party members remained convinced of the propriety of the gold standard and supported McKinley in the election.

Amid a growing national depression where Americans truly recognized the importance of a strong leader with sound economic policies, McKinley garnered over seven million votes. Put simply, the American electorate was energized to elect a strong candidate who they trusted to adequately address the country’s economic woes. Voter turnout was the largest in American history to that date; while both candidates benefitted, McKinley did more so than Bryan.

The electoral vote map of the 1896 election illustrates the stark divide in the country between the industry-rich coasts and the rural middle. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In the aftermath, it is easy to say that it was Bryan’s defeat that all but ended the rise of the Populist Party. Populists had thrown their support to the Democrats who shared similar ideas for the economic rebound of the country and lost. In choosing principle over distinct party identity, the Populists aligned themselves to the growing two-party American political system and would have difficulty maintaining party autonomy afterwards.

Other factors also contributed to the decline of Populism at the close of the century. First, the discovery of vast gold deposits in Alaska during the Klondike Gold Rush of 1896–1899 (also known as the “Yukon Gold Rush”) shored up the nation’s weakening economy and made it possible to thrive on a gold standard. Second, the impending Spanish-American War, which began in 1898, further fueled the economy and increased demand for American farm products. Still, the Populist spirit remained, although it lost some momentum at the close of the nineteenth century. This reformist zeal took on a new form known by the name of Progressivism as the twentieth century unfolded.

9.3 Section Summary

As the economy worsened, more Americans suffered; as the federal government continued to offer few solutions, the Populist movement began to grow. Populist groups approached the 1896 election anticipating that the mass of struggling Americans would support their movement for change. When Democrats chose William Jennings Bryan for their candidate, however, they chose a politician who largely fit the mold of the Populist platform—from his birthplace of Nebraska to his advocacy of the silver standard that most farmers desired. Throwing their support behind Bryan as well, Populists hoped to see a candidate in the White House who would embody the Populist goals, if not the party name. When Bryan lost to Republican William McKinley, the Populist Party lost much of its momentum. As the country climbed out of the depression, the interest in a third party faded away, although the reformist movement remained intact.

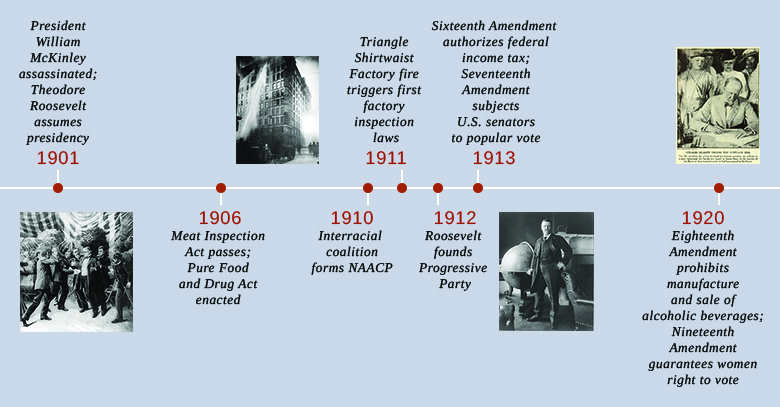

9.4 The Progressive Spirit in America

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the main features of Progressivism

- Identify specific examples of grassroots Progressivism relating to the spread of democracy, efficiency in government, and social justice

- Describe the more radical movements associated with the Progressive Era

The Progressive Era was a time of wide-ranging causes and varied movements, where activists and reformers from diverse backgrounds and with very different agendas pursued their goals of a better America. These reformers were reacting to the challenges that faced the country at the end of the nineteenth century: rapid urban sprawl, immigration, corruption, industrial working conditions, the growth of large corporations, women’s rights, and surging anti-black violence and white supremacy in the South. Investigative journalists of the day, called muckrakers, uncovered social inequality and encouraged Americans to take action. Muckrakers drew public attention to some of the most glaring inequities and scandals that grew out of the social ills of the Gilded Age and the hands-off approach of the federal government since the end of Reconstruction.

The campaigns of the Progressives were often grassroots in their origin. While different causes shared some underlying elements, each movement largely focused on its own goals, be it the right of women to vote, the removal of alcohol from communities, or the desire for a more democratic voting process. What united Progressives beyond their different backgrounds and causes was a set of uniting principles, however. Most strove for a perfection of democracy, which required the expansion of suffrage to worthy citizens and the restriction of political participation for those considered “unfit” on account of health, education, or race. Progressives also agreed that democracy had to be balanced with an emphasis on efficiency, a reliance on science and technology, and deference to the expertise of professionals. They repudiated party politics but looked to government to regulate the modern market economy. And they saw themselves as the agents of social justice and reform, as well as the stewards and guides of workers and the urban poor.

The expressions of these Progressive principles developed at the grassroots level. It was not until Theodore Roosevelt unexpectedly became president in 1901 that the federal government would engage in Progressive reforms. Before then, Progressivism was work done by the people, for the people. What knit Progressives together was the feeling that the country was moving at a dangerous pace in a dangerous direction and required the efforts of everyday Americans to help put it back on track.

One of the key ideals that Progressives considered vital to the growth and health of the country was the concept of a perfected democracy. They felt, quite simply, that Americans needed to exert more control over their government. This shift, they believed, would ultimately lead to a system of government that was better able to address the needs of its citizens. Grassroots Progressives pushed forward their agenda of direct democracy through the passage of state-level reforms.

The first law involved the creation of the direct primary. Prior to this time, the only people who had a hand in selecting candidates for elections were delegates at conventions. Direct primaries allowed party members to vote directly for a candidate, with the nomination going to the one with the most votes. This was the beginning of the current system of holding a primary election before a general election. South Carolina adopted this system for statewide elections in 1896; in 1901, Florida became the first state to use the direct primary in nominations for the presidency. It is the method currently used in three-quarters of U.S. states. Another series of reforms pushed forward by Progressives that sought to sidestep the power of special interests in state legislatures and restore the democratic political process were three election innovations—the initiative, referendum, and recall.

Progressives also pushed for democratic reform that affected the federal government. In an effort to achieve a fairer representation of state constituencies in the U.S. Congress, they lobbied for approval of the Seventeenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which mandated the direct election of U.S. senators. The Seventeenth Amendment replaced the previous system of having state legislatures choose senators. William Jennings Bryan, the 1896 Democratic presidential candidate who received significant support from the Populist Party, was among the leading Progressives who championed this cause.

The 1900 hurricane in Galveston, Texas, claimed more lives than any other natural disaster in American history. In its wake, fearing that the existing corrupt and inefficient government was not up to the job of rebuilding, the remaining residents of the town adopted the commission system of local government. Source: Wikimedia Commons

EXPERTISE AND EFFICIENCY

In addition to making government more directly accountable to the voters, Progressives also fought to rid politics of inefficiency, waste, and corruption. Progressives in large cities were particularly frustrated with the corruption and favoritism of machine politics, which wasted enormous sums of taxpayer money and ultimately stalled the progress of cities for the sake of entrenched politicians, like the notorious Democratic Party Boss William Tweed in New York’s Tammany Hall. Progressives sought to change this corrupt system and had success in places like Galveston, Texas, where, in 1901, they pushed the city to adopt a commission system.

At the state level, perhaps the greatest advocate of Progressive government was Robert La Follette (see picture below). During his time as governor, from 1901 through 1906, La Follette introduced the Wisconsin Idea, wherein he hired experts to research and advise him in drafting legislation to improve conditions in his state. “Fighting Bob” supported numerous Progressive ideas while governor: He signed into law the first workman’s compensation system, approved a minimum wage law, developed a progressive tax law, adopted the direct election of U.S. senators before the subsequent constitutional amendment made it mandatory, and advocated for women’s suffrage. La Follette subsequently served as a popular U.S. senator from Wisconsin from 1906 through 1925, and ran for president on the Progressive Party ticket in 1924

SOCIAL JUSTICE

The Progressives’ work towards social justice took many forms. In some cases, it was focused on those who suffered due to pervasive inequality, such as African Americans, other ethnic groups, and women. In others, the goal was to help those who were in desperate need due to circumstance, such as poor immigrants from southern and eastern Europe who often suffered severe discrimination, the working poor, and those with ill health. Women were in the vanguard of social justice reform. Jane Addams, Lillian Wald, and Ellen Gates Starr, for example, led the settlement house movement of the 1880s (discussed in a previous chapter). Their work to provide social services, education, and health care to working-class women and their children was among the earliest Progressive grassroots efforts in the country.

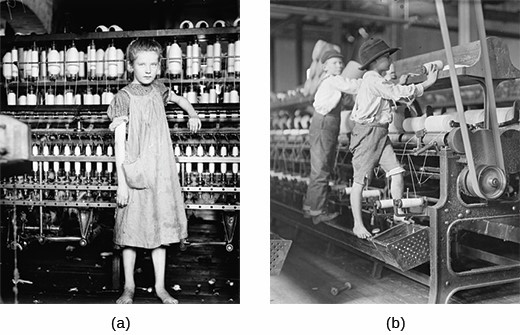

Building on the successes of the settlement houses, social justice reformers took on other, related challenges. The National Child Labor Committee (NCLC), formed in 1904, urged the passage of labor legislation to ban child labor in the industrial sector. In 1900, U.S. census records indicated that one out of every six children between the ages of five and ten were working, a 50-percent increase over the previous decade. If the sheer numbers alone were not enough to spur action, the fact that managers paid child workers noticeably less for their labor gave additional fuel to the NCLC’s efforts to radically curtail child labor.

As part of the National Child Labor Committee’s campaign to raise awareness about the plight of child laborers, Lewis Hine photographed dozens of children in factories around the country, including Addie Card (a), a twelve-year-old spinner working in a mill in Vermont in 1910, and these young boys working at Bibb Mill No. 1 in Macon, Georgia in 1909 (b). Working ten- to twelve-hour shifts, children often worked large machines where they could reach into gaps and remove lint and other debris, a practice that caused plenty of injuries. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Florence Kelley, a Progressive supporter of the NCLC, championed other social justice causes as well. As the first general secretary of the National Consumers League, which was founded in 1899 by Jane Addams and others, Kelley led one of the original battles to try and secure safety in factory working conditions. She particularly opposed sweatshop labor and urged the passage of an eight-hour-workday law in order to specifically protect women in the workplace. Kelley’s efforts were initially met with strong resistance from factory owners who exploited women’s labor and were unwilling to give up the long hours and low wages they paid in order to offer the cheapest possible product to consumers. But in 1911, a tragedy turned the tide of public opinion in favor of Kelley’s cause. On March 25 of that year, a fire broke out at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company on the eighth floor of the Asch building in New York City, resulting in the deaths of 146 garment workers, most of them young, immigrant women (see picture below). Management had previously blockaded doors and fire escapes in an effort to control workers and keep out union organizers; in the blaze, many died due to the crush of bodies trying to evacuate the building. Others died when they fell off the flimsy fire escape or jumped to their deaths to escape the flames. This tragedy provided the National Consumers League with the moral argument to convince politicians of the need to pass workplace safety laws and codes.

|

|

MY STORY |

|

William Shepherd on the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire The tragedy of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire was a painful wake-up call to a country that was largely ignoring issues of poor working conditions and worker health and safety. While this fire was far from the only instance of worker death, the sheer number of people killed—almost one hundred fifty—and the fact they were all young women, made a strong impression. Furthering the power of this tragedy was the first-hand account shared by William Shepherd, a United Press reporter who was on the scene, giving his eyewitness account over a telephone. His account appeared, just two days later, in the Milwaukee Journal, and word of the tragedy spread from there. Public outrage over their deaths was enough to give the National Consumers League the power it needed to push politicians to get involved. I saw every feature of the tragedy visible from outside the building. I learned a new sound—a more horrible sound than description can picture. It was the thud of a speeding, living body on a stone sidewalk. Thud-dead, thud-dead, thud-dead, thud-dead. Sixty-two thud-deads. I call them that, because the sound and the thought of death came to me each time, at the same instant. There was plenty of chance to watch them as they came down. The height was eighty feet. The first ten thud-deads shocked me. I looked up—saw that there were scores of girls at the windows. The flames from the floor below were beating in their faces. Somehow I knew that they, too, must come down. . . . A policeman later went about with tags, which he fastened with wires to the wrists of the dead girls, numbering each with a lead pencil, and I saw him fasten tag no. 54 to the wrist of a girl who wore an engagement ring. A fireman who came downstairs from the building told me that there were at least fifty bodies in the big room on the seventh floor. Another fireman told me that more girls had jumped down an air shaft in the rear of the building. I went back there, into the narrow court, and saw a heap of dead girls. . . . The floods of water from the firemen’s hose that ran into the gutter were actually stained red with blood. I looked upon the heap of dead bodies and I remembered these girls were the shirtwaist makers. I remembered their great strike of last year in which these same girls had demanded more sanitary conditions and more safety precautions in the shops. These dead bodies were the answer. |

|

Another cause that garnered support from a key group of Progressives was the prohibition of liquor. This crusade, which gained followers through the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and the Anti-Saloon League, directly linked Progressivism with morality and Christian reform initiatives, and saw in alcohol both a moral vice and a practical concern, as workingmen spent their wages on liquor and saloons, often turning violent towards each other or their families at home. Through local option votes and subsequent statewide initiatives and referendums, the Anti-Saloon League succeeded in urging 40 percent of the nation’s counties to “go dry” by 1906, and a full dozen states to do the same by 1909. Their political pressure culminated in the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1919, which prohibited the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcoholic beverages nationwide.

This John R. Chapin illustration shows the women of the temperance movement holding an open-air prayer meeting outside an Ohio saloon. Source: Wikimedia Commons

RADICAL PROGRESSIVES

The Progressive Era also witnessed a wave of radicalism, with leaders who believed that America was beyond reform and that only a complete revolution of sorts would bring about the necessary changes. The radicals had early roots in the labor and political movements of the mid-nineteenth century but soon grew to feel that the more moderate Progressive ideals were inadequate. The two most prominent radical movements to emerge at the beginning of the century were the Socialist Party of America (SPA), founded in 1901, and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), founded in 1905, whose emphasis on worker empowerment deviated from the more paternalistic approach of Progressive reformers.

Labor leader Eugene Debs, disenchanted with the failures of the labor movement, was a founding member and prominent leader of the SPA (see picture below). Advocating for change via the ballot box, the SPA sought to elect Socialists to positions at the local, state, and federal levels in order to initiate change from within. Between 1901 and 1918, the SPA enjoyed tremendous success, electing over seventy Socialist mayors, over thirty state legislators, and two U.S. congressmen, Victor Berger from Wisconsin and Meyer London from New York. Debs himself ran for president as the SPA candidate in five elections between 1900 and 1920, twice earning nearly one million votes.

William “Big Bill” Haywood formed the radical IWW, or Wobblies, in 1905. Although he remained an active member of the Socialist Party until 1919, Haywood appreciated the outcry of the more radical arm of the party that desired an industrial union approach to labor organization. The IWW advocated for direct action and, in particular, the general strike, as the most effective revolutionary method to overthrow the capitalist system. By 1912, the Wobblies had played a significant role in a number of major strikes, including the Paterson Silk Strike, the Lawrence Textile Strike, and the Mesabi Range Iron Strike. The government viewed the Wobblies as a significant threat, and in a response far greater than their actions warranted, targeted them with arrests, tar-and-featherings, shootings, and lynchings.

Both the Socialist Party and the IWW reflected elements of the Progressive desire for democracy and social justice. The difference was simply that for this small but vocal minority in the United States, the corruption of government at all levels meant that the desire for a better life required a different approach. What they sought mirrored the work of all grassroots Progressives, differing only in degree and strategy.

9.4 Section Summary

In its first decade, the Progressive Era was a grassroots effort that ushered in reforms at state and local levels. At the beginning of the twentieth century, however, Progressive endeavors captured the attention of the federal government. The challenges of the late nineteenth century were manifold: fast growing cities that were ill-equipped to house the working poor, hands-off politicians shackled into impotence by their system of political favors, and rural Americans struggling to keep their farms afloat. The movement counted African Americans, both women and men, and urban as well as rural dwellers among its ranks. Progressive causes ranged from anti-liquor campaigns to fair pay. Together, Progressives sought to advance the spread of democracy, improve efficiency in government and industry, and promote social justice. But what tied together these disparate causes and groups was the belief that the country was in dire need of reform, and that answers were to be found within the activism and expertise of predominantly middle-class Americans on behalf of troubled communities. At the beginning of the twentieth century, a more radical, revolutionary breed of Progressivism began to evolve. While these radical Progressives generally shared the goals of their more mainstream counterparts, their strategies differed significantly. Mainstream Progressives and many middle-class Americans feared groups such as the Socialist Party of America and the Industrial Workers of the World, which emphasized workers’ empowerment and direct action.

9.5 New Voices for Women and African Americans

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand the origins and growth of the women’s rights movement

- Identify the different strands of the early African American civil rights movement

The Progressive drive for a more perfect democracy and social justice also fostered the growth of two new movements that attacked the oldest and most long-standing betrayals of the American promise of equal opportunity and citizenship—the disfranchisement of women and civil rights for African Americans.

LEADERS EMERGE IN THE WOMEN’S MOVEMENT

Women like Jane Addams and Florence Kelley were instrumental in the early Progressive settlement house movement, and female leaders dominated organizations such as the WCTU and the Anti-Saloon League. From these earlier efforts came new leaders who, in their turn, focused their efforts on the key goal of the Progressive Era as it pertained to women: the right to vote.

Women had first formulated their demand for the right to vote in the Declaration of Sentiments at a convention in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848, and saw their first opportunity of securing suffrage during Reconstruction when legislators—driven by racial animosity—sought to enfranchise women to counter the votes of black men following the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment. By 1900, the western frontier states of Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming had already responded to women’s movements with the right to vote in state and local elections, regardless of gender. They conceded to the suffragists’ demands, partly in order to attract more women to these male-dominated regions.

In 1890, the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA) organized several hundred state and local chapters to urge the passage of a federal amendment to guarantee a woman’s right to vote. Under the leadership of Carrie Chapman Catt, beginning in 1900, the group decided to make suffrage its first priority. Soon, its membership began to grow. Using modern marketing efforts like celebrity endorsements to attract a younger audience, the NAWSA became a significant political pressure group for the passage of an amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Women suffragists in Ohio sought to educate and convince men that they should support a woman’s rights to vote. As the feature below on the backlash against suffragists illustrates, it was a far from simple task. Source: Wikimedia Commons

For some in the NAWSA, however, the pace of change was too slow. Frustrated with the lack of response by state and national legislators, Alice Paul, who joined the organization in 1912, sought to expand the scope of the organization as well as to adopt more direct protest tactics to draw greater media attention. When others in the group were unwilling to move in her direction, Paul split from the NAWSA to create the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage, later renamed the National Woman’s Party, in 1913. Known as the Silent Sentinels, Paul and her group picketed outside the White House for nearly two years, starting in 1917. In the latter stages of their protests, many women, including Paul, were arrested and thrown in jail, where they staged a hunger strike as self-proclaimed political prisoners. Prison guards ultimately force-fed Paul to keep her alive. At a time—during World War I—when women volunteered as army nurses, worked in vital defense industries, and supported Wilson’s campaign to “make the world safe for democracy,” the scandalous mistreatment of Paul embarrassed President Woodrow Wilson. Enlightened to the injustice toward all American women, he changed his position in support of a woman’s constitutional right to vote.

While Catt and Paul used different strategies, their combined efforts brought enough pressure to bear for Congress to pass the Nineteenth Amendment, which prohibited voter discrimination on the basis of sex, during a special session in the summer of 1919. Subsequently, the required thirty-six states approved its adoption, with Tennessee doing so in August of 1920, in time for that year’s presidential election.

Alice Paul and her Silent Sentinels picketed outside the White House for almost two years, and, when arrested, went on hunger strike until they were force-fed in order to save their lives. Source: Wikimedia Commons

LEADERS EMERGE IN THE EARLY CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

Racial mob violence against African Americans permeated much of the “New South”—and, to a lesser extent, the West, where Mexican Americans and other immigrant groups also suffered severe discrimination and violence—by the late nineteenth century. The Ku Klux Klan and a system of Jim Crow laws governed much of the South (discussed in a previous chapter). White middle-class reformers were appalled at the violence of race relations in the nation but typically shared the belief in racial characteristics and the superiority of Anglo-Saxon whites over African Americans, Asians, “ethnic” Europeans, Indians, and Latin American populations. Southern reformers considered segregation a Progressive solution to racial violence; across the nation, educated middle-class Americans enthusiastically followed the work of eugenicists who identified virtually all human behavior as inheritable traits and issued awards at county fairs to families and individuals for their “racial fitness.” It was against this tide that African American leaders developed their own voice in the Progressive Era, working along diverse paths to improve the lives and conditions of African Americans throughout the country.

Born into slavery in Virginia in 1856, Booker T. Washington became an influential African American leader at the outset of the Progressive Era. In 1881, he became the first principal for the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in Alabama, a position he held until he died in 1915. Tuskegee was an all-black “normal school”—an old term for a teachers’ college—teaching African Americans a curriculum geared towards practical skills such as cooking, farming, and housekeeping. Graduates would often then travel through the South, teaching new farming and industrial techniques to rural communities.

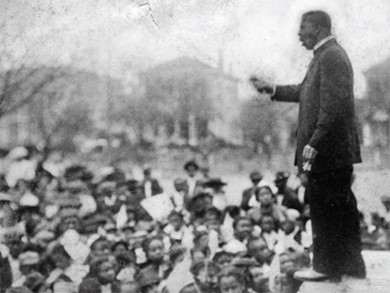

In Booker T. Washington’s speech at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, he urged his audience to “cast down your bucket where you are.” Source: Wikimedia Commons

In a speech delivered at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta in 1895, which was meant to promote the economy of a “New South,” Washington proposed what came to be known as the Atlanta Compromise. Speaking to a racially mixed audience, Washington called upon African Americans to work diligently for their own uplift and prosperity rather than preoccupy themselves with political and civil rights. Their success and hard work, he implied, would eventually convince southern whites to grant these rights. Not surprisingly, most whites liked Washington’s model of race relations, since it placed the burden of change on blacks and required nothing of them. At the same time, his message also appealed to many in the black community, and some attribute this widespread popularity to his consistent message that social and economic growth, even within a segregated society, would do more for African Americans than an all-out agitation for equal rights on all fronts. Yet, many African Americans disagreed with Washington’s approach. Much in the same manner that Alice Paul felt the pace of the struggle for women’s rights was moving too slowly under the NAWSA, some within the African American community felt that immediate agitation for the rights guaranteed under the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments, established during the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, was necessary

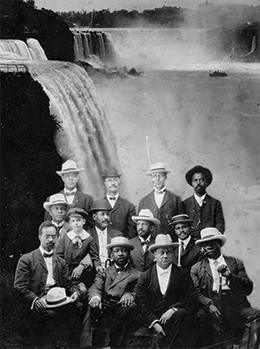

In 1905, a group of prominent civil rights leaders, led by W. E. B. Du Bois, met in a small hotel on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls—where segregation laws did not bar them from hotel accommodations—to discuss what immediate steps were needed for equal rights. Du Bois, a professor at the all-black Atlanta University and the first African American with a doctorate from Harvard, emerged as the prominent spokesperson for what would later be dubbed the Niagara Movement. By 1905, he had grown wary of Booker T. Washington’s calls for African Americans to accommodate white racism and focus solely on self-improvement. Du Bois, and others alongside him, wished to carve a more direct path towards equality that drew on the political leadership and litigation skills of the black, educated elite, which he termed the “talented tenth.”

This photo of the Niagara Movement shows W. E. B. Du Bois seated in the second row, center, in the white hat. The proud and self-confident postures of this group stood in marked contrast to the humility that Booker T. Washington urged of blacks. Source: Wikimedia Commons

At the meeting, Du Bois led the others in drafting the “Declaration of Principles,” which called for immediate political, economic, and social equality for African Americans. These rights included universal suffrage, compulsory education, and the elimination of the convict lease system in which tens of thousands of blacks had endured slavery-like conditions in southern road construction, mines, prisons, and penal farms since the end of Reconstruction. Within a year, Niagara chapters had sprung up in twenty-one states across the country. By 1908, internal fights over the role of women in the fight for African American equal rights lessened the interest in the Niagara Movement. But the movement laid the groundwork for the creation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1909.

In both Washington and Du Bois, African Americans found leaders to push forward the fight for their place in the new century, each with a very different strategy. Both men cultivated ground for a new generation of African American spokespeople and leaders who would then pave the road to the modern civil rights movement after World War II.

9.5 Section Summary

The Progressive commitment to promoting democracy and social justice created an environment within which the movements for women’s and African American rights grew and flourished. Emergent leaders such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Carrie Chapman Catt, and Alice Paul spread the cause of woman suffrage, drawing in other activists and making the case for a constitutional amendment ensuring a woman’s right to vote. African Americans—guided by leaders such as Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois—strove for civil rights and economic opportunity, although their philosophies and strategies differed significantly. In the women’s and civil rights movements alike, activists both advanced their own causes and paved the way for later efforts aimed at expanding equal opportunity and citizenship.

9.6 Progressivism in the White House

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the key features of Theodore Roosevelt’s “Square Deal”

- Explain the key features of William Howard Taft’s Progressive agenda

- Identify the main pieces of legislation that Woodrow Wilson’s “New Freedom” agenda comprised

Progressive groups made tremendous strides on issues involving democracy, efficiency, and social justice. But they found that their grassroots approach was ill-equipped to push back against the most powerful beneficiaries of growing inequality, economic concentration, and corruption—big business. In their fight against the trusts, Progressives needed the leadership of the federal government, and they found it in Theodore Roosevelt in 1901, through an accident of history.

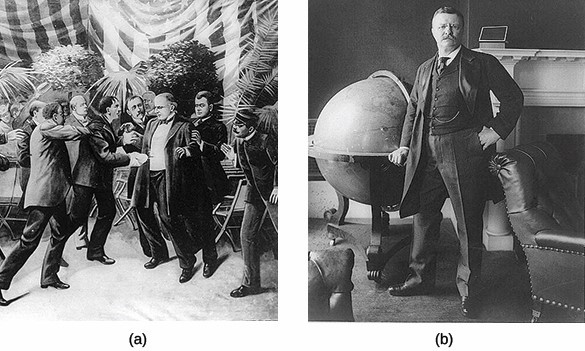

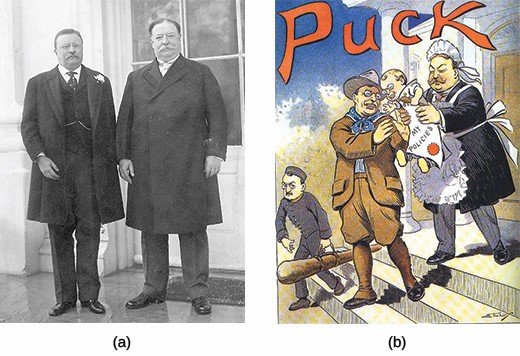

President William McKinley’s assassination (a) at the hands of an anarchist made Theodore Roosevelt (b) the country’s youngest president. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In 1900, a sound economic recovery, a unifying victory in the Spanish-American War, and the annexation of the Philippines had helped President William McKinley secure his reelection with the first solid popular majority since 1872. His new vice president was former New York Governor and Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt. But when an assassin shot and killed President McKinley in 1901 at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, Theodore Roosevelt unexpectedly became the youngest president in the nation’s history. More importantly, it ushered in a new era of progressive politics and changed the role of the presidency for the twentieth century.

BUSTING THE TRUSTS

As the new president, Roosevelt moved cautiously with his agenda while he finished out McKinley’s term. Roosevelt kept much of McKinley’s cabinet intact, and his initial message to Congress gave only one overriding Progressive goal for his presidency: to eliminate business trusts. In the three years prior to Roosevelt’s presidency, the nation had witnessed a wave of mergers and the creation of mega-corporations. Roosevelt used the presidency as a “bully pulpit” to publicly denounce “bad trusts”—those corporations that exploited their market positions for short-term gains—before he ordered prosecutions by the Justice Department. In total, Roosevelt initiated over two dozen successful anti-trust suits, more than any president before him.

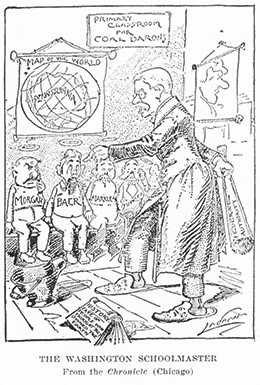

This cartoon shows President Roosevelt disciplining coal barons like J. P. Morgan, threatening to beat them with a stick labeled “Federal Authority.” It illustrates Roosevelt’s new approach to business. Source: Wikimedia Commons

THE SQUARE DEAL

Roosevelt won his second term in 1904 with an overwhelming 57 percent of the popular vote. After the election, he moved quickly to enact his own brand of Progressivism, which he called a Square Deal for the American people. Early in his second term, Roosevelt read muckraker Upton Sinclair’s 1905 novel and exposé on the meatpacking industry, The Jungle. Although Roosevelt initially questioned the book due to Sinclair’s professed Socialist leanings, a subsequent presidential commission investigated the industry and corroborated the deplorable conditions under which Chicago’s meatpackers processed meats for American consumers. Alarmed by the results and under pressure from an outraged public disgusted with the revelations, Roosevelt moved quickly to protect public health. He urged the passage of two laws to do so. The first, the Meat Inspection Act of 1906, established a system of government inspection for meat products, including grading the meat based on its quality. This standard was also used for imported meats. The second was the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which required labels on all food and drug products that clearly stated the materials in the product. The law also prohibited any “adulterated” products, a measure aimed at some specific, unhealthy food preservatives.

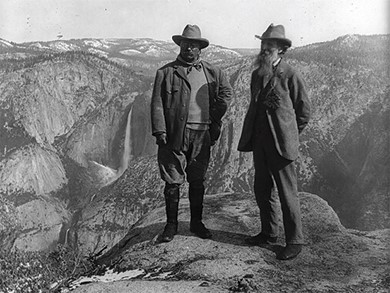

Another key element of Roosevelt’s Progressivism was the protection of public land. Roosevelt was a longtime outdoorsman, with an interest that went back to his childhood and college days, as well as his time cattle ranching in the West, and he chose to appoint his good friend Gifford Pinchot as the country’s first chief of the newly created U.S. Forestry Service. Under Pinchot’s supervision, the department carved out several nature habitats on federal land in order to preserve the nation’s environmental beauty and protect it from development or commercial use. Apart from national parks like Oregon’s Crater Lake or Colorado’s Mesa Verde, and monuments designed for preservation, Roosevelt conserved public land for regulated use for future generations. To this day, the 150 national forests created under Roosevelt’s stewardship carry the slogan “land of many uses.” In all, Roosevelt established eighteen national monuments, fifty-one federal bird preserves, five national parks, and over one hundred fifty national forests, which amounted to about 230 million acres of public land.

Theodore Roosevelt’s interest in the protection of public lands was encouraged by conservationists such as John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club, with whom he toured Yosemite National Park in California, ca. 1906. Source: Wikimedia Commons

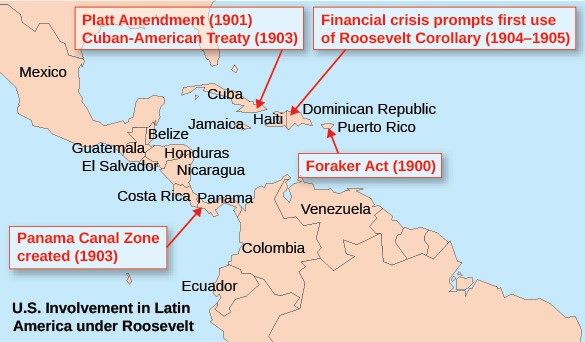

Theodore Roosevelt’s progressivism also included a new vision of the role of the United States in world affairs. His foreign policy approach was summarized in his statement, allegedly based on a favorite African proverb, that the US should “speak softly, and carry a big stick, and you will go far”. At the crux of his foreign policy was a thinly veiled threat. Roosevelt believed that in light of the country’s recent military successes, it was unnecessary to use force to achieve foreign policy goals, so long as the military could threaten force. This rationale also rested on the young president’s philosophy, which he termed the “strenuous life,” and that prized challenges overseas as opportunities to instill American men with the resolve and vigor they allegedly had once acquired in the Trans-Mississippi West.

Roosevelt believed that while the coercive power wielded by the United States could be harmful in the wrong hands, the Western Hemisphere’s best interests were also the best interests of the United States. He felt, in short, that the United States had the right and the obligation to be the policeman of the hemisphere. This belief, and his strategy of “speaking softly and carrying a big stick,” shaped much of Roosevelt’s foreign policy.

Roosevelt was often depicted in cartoons wielding his “big stick” and pushing the U.S. foreign agenda, often through the power of the U.S. Navy. Source: Wikimedia Commons

THE ROOSEVELT COROLLARY

As President, Roosevelt wanted to send a clear message to the rest of the world—and in particular to his European counterparts—that the colonization of the Western Hemisphere had now ended, and their interference in the countries there would no longer be tolerated. At the same time, he sent a message to his counterparts in Central and South America, should the United States see problems erupt in the region, that it would intervene in order to maintain peace and stability throughout the hemisphere.

Roosevelt articulated this seeming double standard in a 1904 address before Congress, in a speech that became known as the Roosevelt Corollary. The Roosevelt Corollary was based on the original Monroe Doctrine of the early nineteenth century, which warned European nations of the consequences of their interference in the Caribbean. In this addition, Roosevelt states that the United States would use military force “as an international police power” to correct any “chronic wrongdoing” by any Latin American nation that might threaten stability in the region. Unlike the Monroe Doctrine, which proclaimed an American policy of noninterference with its neighbors’ affairs, the Roosevelt Corollary loudly proclaimed the right and obligation of the United States to involve itself whenever necessary.

|

|

DEFINING “AMERICAN” |

|

The Roosevelt Corollary and Its Impact In 1904, Roosevelt put the United States in the role of the “police power” of the Western Hemisphere and set a course for the U.S. relationship with Central and Latin America that played out over the next several decades. He did so with the Roosevelt Corollary, in which he stated: It is not true that the United States feels any land hunger or entertains any projects as regards the other nations of the Western Hemisphere save as such are for their welfare. All that this country desires is to see the neighboring countries stable, orderly, and prosperous. Any country whose people conduct themselves well can count upon our hearty friendship. . . Chronic wrongdoing, or an impotence which results in a general loosening of the ties of civilized society, may in America, as elsewhere, require intervention by some civilized nation, and in the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, however, reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power.” In the twenty years after he made this statement, the United States used military force in Latin America over a dozen times. The Roosevelt Corollary was used as a rationale for American involvement in the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, Haiti, and other Latin American countries, straining relations between Central America and its dominant neighbor to the north throughout the twentieth century. |

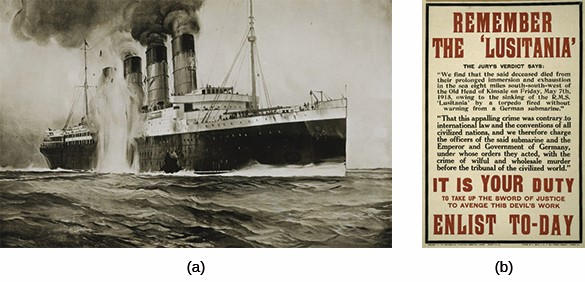

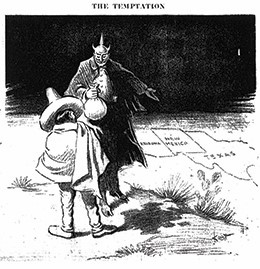

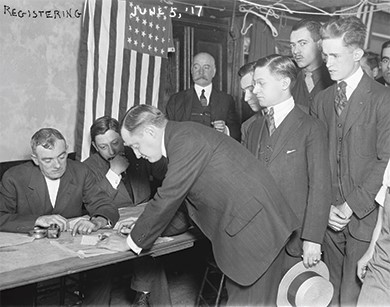

|