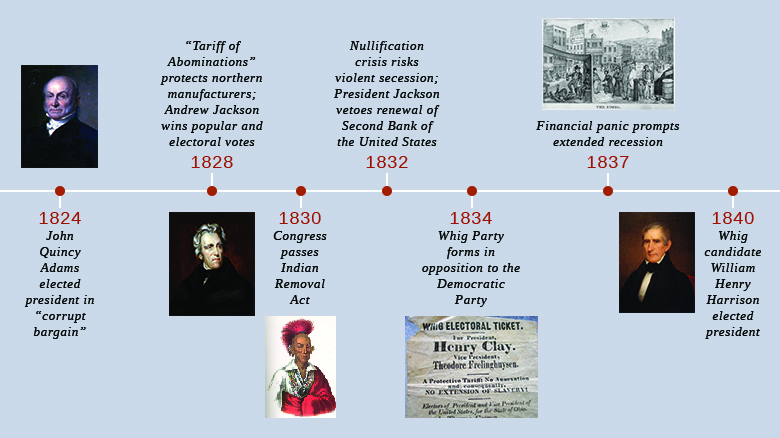

5 Chapter 5: Jacksonian Democracy and Westward Settlement, 1820–1850

Jacksonian Democracy and Westward Settlement, 1820–1850

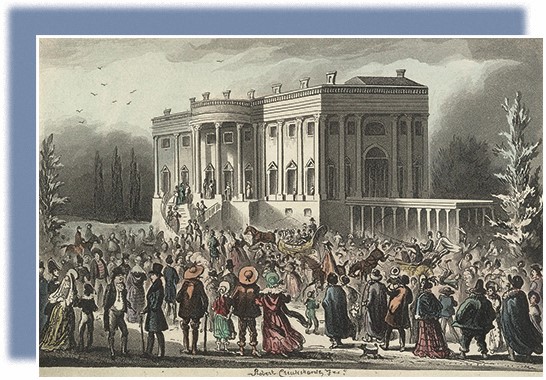

In President’s Levee, or all Creation going to the White House, Washington (1841), by Robert Cruikshank, the artist depicts Andrew Jackson’s inauguration in 1829, with crowds surging into the White House to join the celebrations. Rowdy revelers destroyed many White House furnishings in their merriment. A new political era of democracy had begun, one characterized by the rule of the majority. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Chapter Outline

Introduction, Watch and Learn, Questions to Guide Your Reading

5.1 Industrialization and the Market Revolution

5.2 A Vibrant Capitalist Republic

5.3 A New Political Style: From John Quincy Adams to Andrew Jackson

5.4 The Rise of American Democracy

5.5 Indian Removal

5.7 The Mexican-American War, 1846-1848

5.8 Free Soil or Slave? The Dilemma of the West

Summary Timelines, Chapter 5 Self-Test, Chapter 5 Key Terms Crossword Puzzle

Introduction

By the 1830s, the United States had developed a thriving industrial and commercial sector in the Northeast. Farmers embraced regional and distant markets as the primary destination for their products. Artisans witnessed the methodical division of the labor process in factories. Wage labor became an increasingly common experience. These industrial and market revolutions, combined with advances in transportation, transformed the economic and social landscape. Americans could now quickly produce larger amounts of goods for a nationwide, and sometimes an international, market and rely less on foreign imports than in colonial times. As American economic life shifted rapidly and modes of production changed, new class divisions emerged and solidified, resulting in previously unknown economic and social inequalities

The most extraordinary political development in the years before the Civil War was the rise of American democracy. Whereas the founders envisioned the United States as a republic, not a democracy, and had placed safeguards such as the Electoral College in the 1787 Constitution to prevent simple majority rule, the early 1820s saw many Americans embracing majority rule and rejecting old forms of deference that were based on elite ideas of virtue, learning, and family lineage.

A new breed of politicians learned to harness the magic of the many by appealing to the resentments, fears, and passions of ordinary citizens to win elections. The charismatic Andrew Jackson gained a reputation as a fighter and defender of American expansion, emerging as the quintessential figure leading the rise of American democracy. In the image at the beginning of the chapter, crowds flock to the White House to celebrate his inauguration as president. While earlier inaugurations had been reserved for Washington’s political elite, Jackson’s was an event for the people, so much so that the pushing throngs caused thousands of dollars of damage to White House property. Characteristics of modern American democracy, including the turbulent nature of majority rule, first appeared during the Age of Jackson.

After 1800, the United States militantly expanded westward across North America, confident of its right and duty to gain control of the continent and spread the benefits of its “superior” culture. Efforts to seize western territories from native peoples and expand the republic by warring with Mexico succeeded beyond expectations. Few nations ever expanded so quickly. Yet, this expansion led to debates about the fate of slavery in the West, creating tensions between North and South that ultimately led to the collapse of American democracy and a brutal civil war.

Watch and Learn (Crash Course in US History Videos for chapter 5)

Questions to Guide Your Reading:

- What were some of the social and cultural beliefs that became widespread during the Age of Jackson? What lay behind these beliefs, and do you observe any of them in American culture today?

- Were the political changes of the early nineteenth century positive or negative? Explain your opinion.

- If you were defending the Cherokee and other native nations before the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1830s, what arguments would you make? If you were supporting Indian removal, what arguments would you make?

- How did depictions of Indians in popular culture help to sway popular opinion to support Indian removal? Does modern popular culture continue to wield this kind of power over us? Why or why not?

- Consider the annexation of Texas and the Mexican-American War from a Mexican perspective. What would you find objectionable about American actions, foreign policy, and attitudes in the 1840s?

- Consider the arguments over the expansion of slavery made by both northerners and southerners in the aftermath of the U.S. victory over Mexico. Who had the more compelling case? Or did each side make equally significant arguments?

5.1 Industrialization and the Market Revolution

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Understand industrialization’s impact on the nature of production and work

- Describe the effect of industrialization on consumption

Northern industrialization expanded rapidly following the War of 1812. Industrialized manufacturing began in New England, where wealthy merchants built water-powered textile mills (and mill towns to support them) along the rivers of the Northeast. These mills introduced new modes of production centralized within the confines of the mill itself. As never before, production relied on mechanized sources with water power, and later steam, to provide the force necessary to drive machines. In addition to the mechanization and centralization of work in the mills, specialized, repetitive tasks assigned to wage laborers replaced earlier modes of handicraft production done by artisans at home. The operations of these mills irrevocably changed the nature of work by deskilling tasks, breaking down the process of production to its most basic, elemental parts. In return for their labor, the workers, who at first were young women from rural New England farming families, received wages. From its origin in New England, manufacturing soon spread to other regions of the United States.

THE RISE OF CONSUMERISM

At the end of the eighteenth century, most American families lived in candlelit homes with bare floors and unadorned walls, cooked and warmed themselves over fireplaces, and owned few changes of clothing. All manufactured goods were made by hand and, as a result, were usually scarce and fairly expensive. The automation of the manufacturing process changed that, making consumer goods that had once been thought of as luxury items widely available for the first time. Now all but the very poor could afford the necessities and some of the small luxuries of life. Rooms were lit by oil lamps, which gave brighter light than candles. Homes were heated by parlor stoves, which allowed for more privacy; people no longer needed to huddle together around the hearth. Iron cookstoves with multiple burners made it possible for housewives to prepare more elaborate meals. Many people could afford carpets and upholstered furniture, and even farmers could decorate their homes with curtains and wallpaper. Clocks, which had once been quite expensive, were now within the reach of most ordinary people.

THE WORK EXPERIENCE TRANSFORMED

As production became mechanized and relocated to factories, the experience of workers underwent significant changes. Farmers and artisans had controlled the pace of their labor and the order in which things were done. If an artisan wanted to take the afternoon off, he could. If a farmer wished to rebuild his fence on Thursday instead of on Wednesday, he could. They conversed and often drank during the workday. Indeed, journeymen were often promised alcohol as part of their wages. One member of the group might be asked to read a book or a newspaper aloud to the others. In the warm weather, doors and windows might be opened to the outside, and work stopped when it was too dark to see.

Work in factories proved to be quite different. Employees were expected to report at a certain time, usually early in the morning, and to work all day. They could not leave when they were tired or take breaks other than at designated times. Those who arrived late found their pay docked; five minutes’ tardiness could result in several hours’ worth of lost pay, and repeated tardiness could result in dismissal. The monotony of repetitive tasks made days particularly long. Hours varied according to the factory, but most factory employees toiled ten to twelve hours a day, six days a week. In the winter, when the sun set early, oil lamps were used to light the factory floor, and employees strained their eyes to see their work and coughed as the rooms filled with smoke from the lamps. In the spring, as the days began to grow longer, factories held “blowing-out” celebrations to mark the extinguishing of the oil lamps. These “blow-outs” often featured processions and dancing.

Freedom within factories was limited. Drinking was prohibited. Some factories did not allow employees to sit down. Doors and windows were kept closed, especially in textile factories where fibers could be easily disturbed by incoming breezes, and mills were often unbearably hot and humid in the summer. In the winter, workers often shivered in the cold. In such environments, workers’ health suffered.

The workplace posed other dangers as well. The presence of cotton bales alongside the oil used to lubricate machines made fire a common problem in textile factories. Workplace injuries were also common. Workers’ hands and fingers were maimed or severed when they were caught in machines; in some cases, their limbs or entire bodies were crushed. Workers who didn’t die from such injuries almost certainly lost their jobs, and with them, their income. Corporal punishment of both children and adults was common in factories; where abuse was most extreme, children sometimes died as a result of injuries suffered at the hands of an overseer.

WORKERS AND THE LABOR MOVEMENT

Many workers undoubtedly enjoyed some of the new wage opportunities factory work presented. For many of the young New England women who ran the machines in Waltham, Lowell, and elsewhere, the experience of being away from the family was exhilarating and provided a sense of solidarity among them. Though most sent a large portion of their wages home, having even a small amount of money of their own was a liberating experience, and many used their earnings to purchase clothes, ribbons, and other consumer goods for themselves.

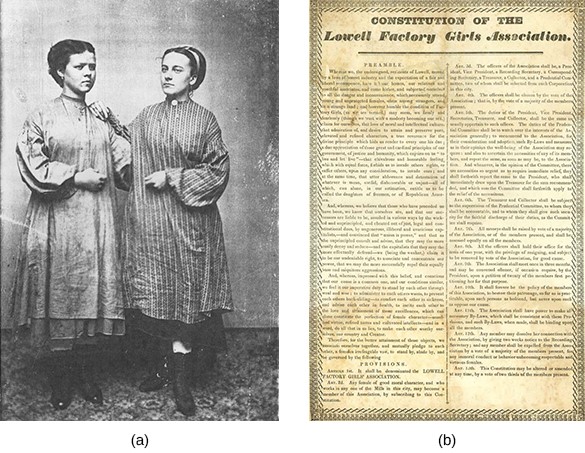

New England mill workers were often young women, as seen in this early tintype made ca. 1870 (a). When management proposed rent increases for those living in company boarding houses, female textile workers in Lowell responded by forming the Lowell Factory Girls Association—its constitution is shown in image (b)—in 1836 and organizing a “turn-out” or strike. Soucce: Wikimedia Commons

The long hours, strict discipline, and low wages, however, soon led workers to organize to protest their working conditions and pay. In 1821, the young women employed by the Boston Manufacturing Company in Waltham went on strike for two days when their wages were cut. In 1824, workers in Pawtucket struck to protest reduced pay rates and longer hours, the latter of which had been achieved by cutting back the amount of time allowed for meals. Similar strikes occurred at Lowell and in other mill towns like Dover, New Hampshire, where the women employed by the Cocheco Manufacturing Company ceased working in December 1828 after their wages were reduced. In the 1830s, female mill operatives in Lowell formed the Lowell Factory Girls Association to organize strike activities in the face of wage cuts and, later, established the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association to protest the twelve-hour workday. Even though strikes were rarely successful, and workers usually were forced to accept reduced wages and increased hours, work stoppages as a form of labor protest represented the beginnings of the labor movement in the United States.

|

|

DEFINING “AMERICAN” |

|

Michel Chevalier on Mill Worker Rules and Wages In the 1830s, the French government sent engineer and economist Michel Chevalier to study industrial and financial affairs in Mexico and the United States. In 1839, he published Society, Manners, and Politics in the United States, in which he recorded his impressions of the Lowell textile mills. In the excerpt below, Chevalier describes the rules and wages of the Lawrence Company in 1833. “All persons employed by the Company must devote themselves assiduously to their duty during working-hours. They must be capable of doing the work which they undertake, or use all their efforts to this effect. They must on all occasions, both in their words and in their actions, show that they are penetrated by a laudable love of temperance and virtue, and animated by a sense of their moral and social obligations. The Agent of the Company shall endeavour to set to all a good example in this respect. Every individual who shall be notoriously dissolute, idle, dishonest, or intemperate, who shall be in the practice of absenting himself from divine service, or shall violate the Sabbath, or shall be addicted to gaming, shall be dismissed from the service of the Company. … All ardent spirits are banished from the Company’s grounds, except when prescribed by a physician. All games of hazard and cards are prohibited within their limits and in the boarding-houses.” Weekly wages were as follows: For picking and carding, $2.78 to $3.10 For spinning, $3.00 For weaving, $3.10 to $3.12 For warping and sizing, $3.45 to $4.00 For measuring and folding, $3.12 |

|

5.1 Section Summary

Industrialization led to radical changes in American life. New industrial towns, like Waltham, Lowell, and countless others, dotted the landscape of the Northeast. The mills provided many young women an opportunity to experience a new and liberating life, and these workers relished their new freedom. Workers also gained a greater appreciation of the value of their work and, in some instances, began to question the basic fairness of the new industrial order. The world of work had been fundamentally reorganized. In this age of entrepreneurship, in which those who invested their money wisely in land, business ventures, or technological improvements reaped vast profits, inventors produced new wonders that transformed American life.

5.2 A Vibrant Capitalist Republic

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify key American innovators and inventors

- Describe changes in the US economy in the 19th century

- Identify the ways in which railroads impacted Americans’ lives in the nineteenth century

By the 1840s, the United States economy bore little resemblance to the import-and-export economy of colonial days. It was now a market economy, one in which the production of goods, and their prices, were unregulated by the government. Commercial centers, to which job seekers flocked, mushroomed. New York City’s population skyrocketed. In 1790, it was 33,000; by 1820, it had reached 200,000; and by 1825, it had swelled to 270,000. New opportunities for wealth appeared to be available to anyone.

However, the expansion of the American economy made it prone to the boom-and-bust cycle. Market economies involve fluctuating prices for labor, raw materials, and consumer goods and depend on credit and financial instruments—any one of which can be the source of an imbalance and an economic downturn in which businesses and farmers default, wage workers lose their employment, and investors lose their assets.

THE PANIC OF 1819

The first major economic crisis in the United States after the War of 1812 was due, in large measure, to factors in the larger Atlantic economy. It was made worse, however, by land speculation and poor banking practices at home. British textile mills voraciously consumed American cotton, and the devastation of the Napoleonic Wars made Europe reliant on other American agricultural commodities such as wheat. This drove up both the price of American agricultural products and the value of the land on which staples such as cotton, wheat, corn, and tobacco were grown.

Many Americans were struck with “land fever.” Farmers strove to expand their acreage, and those who lived in areas where unoccupied land was scarce sought holdings in the West. They needed money to purchase this land, however. Small merchants and factory owners, hoping to take advantage of this boom time, also sought to borrow money to expand their businesses. When existing banks refused to lend money to small farmers and others without a credit history, state legislatures chartered new banks to meet the demand. In one legislative session, Kentucky chartered forty-six. As loans increased, paper money from new state banks flooded the country, creating inflation that drove the price of land and goods still higher. This, in turn, encouraged even more people to borrow money with which to purchase land or to expand or start their own businesses. Speculators took advantage of this boom in the sale of land by purchasing property not to live on, but to buy cheaply and resell at exorbitant prices.

The inflated economic bubble burst in 1819, resulting in a prolonged economic depression or severe downturn in the economy called the Panic of 1819. It was the first economic depression experienced by the American public, who panicked as they saw the prices of agricultural products fall and businesses fail. Prices had already begun falling in 1815, at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, when Britain began to “dump” its surplus manufactured goods, the result of wartime overproduction, in American ports, where they were sold for low prices and competed with American-manufactured goods. In 1818, to make the economic situation worse, prices for American agricultural products began to fall both in the United States and in Europe; the overproduction of staples such as wheat and cotton coincided with the recovery of European agriculture, which reduced demand for American crops. Crop prices tumbled by as much 75 percent.

This dramatic decrease in the value of agricultural goods left farmers unable to pay their debts. As they defaulted on their loans, banks seized their property. However, because the drastic fall in agricultural prices had greatly reduced the value of land, the banks were left with farms they were unable to sell. Land speculators lost the value of their investments. As the countryside suffered, hard-hit farmers ceased to purchase manufactured goods. Factories responded by cutting wages or firing employees.

In an effort to stimulate the economy in the midst of the economic depression, Congress passed several acts modifying land sales. The Land Law of 1820 lowered the price of land to $1.25 per acre and allowed small parcels of eighty acres to be sold. The Relief Act of 1821 allowed settlers to return land to the government if they could not afford to keep it. The money they received in return was credited toward their debt. The act also extended the credit period to eight years. States, too, attempted to aid those faced with economic hard times by passing laws to prevent mortgage foreclosures so buyers could keep their homes. Americans made the best of the opportunities presented in business, in farming, or on the frontier, and by 1823 the Panic of 1819 had ended. The recovery provided ample evidence of the vibrant and resilient nature of the American people.

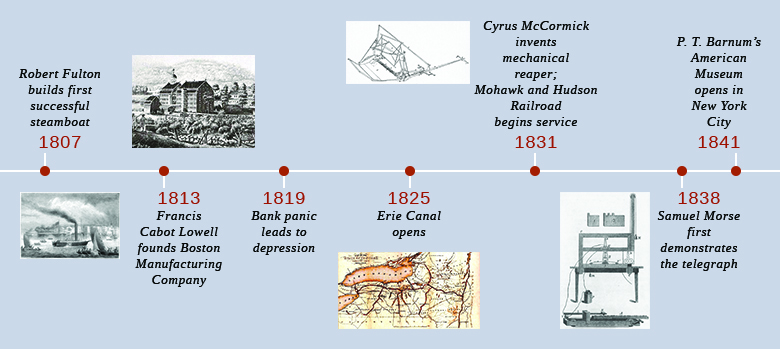

ENTREPRENEURS AND INVENTORS

The U.S. economy was also bolstered by the creative energies of its citizens in the years before the Civil War as a frenzy of entrepreneurship and invention yielded many new products and machines. The republic seemed to be a laboratory of innovation, and technological advances appeared unlimited.

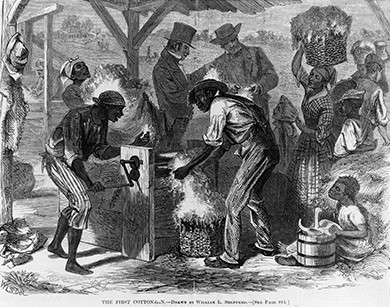

One of the most influential advancements of the early nineteenth century was the cotton engine or gin, invented by Eli Whitney and patented in 1794. Whitney, who was born in Massachusetts, had spent time in the South and knew that a device to speed up the production of cotton was desperately needed so cotton farmers could meet the growing demand for their crop. He hoped the cotton gin would render slavery obsolete. Whitney’s seemingly simple invention cleaned the seeds from the raw cotton far more quickly and efficiently than could enslaved people working by hand. The raw cotton with seeds was placed in the cotton gin, and with the use of a hand crank, the seeds were extracted through a carding device that aligned the cotton fibers in strands for spinning.

Whitney also worked on machine tools, devices that cut and shaped metal to make standardized, interchangeable parts for other mechanical devices like clocks and guns. Whitney’s machine tools to manufacture parts for muskets enabled guns to be manufactured and repaired by people other than skilled gunsmiths. His creative genius served as a source of inspiration for many other American inventors.

“The First Cotton-Gin,” an 1869 drawing by William L. Sheppard, shows the first use of a cotton gin “at the close of the last century.” African American slaves handle the gin while white men conduct business in the background. Source: Wikimedia Commons

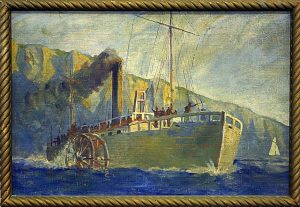

Another influential new technology of the early 1800s was the steamship engine, invented by Robert Fulton in 1807. Fulton’s first steamship, the Clermont, used paddle wheels to travel the 150 miles from New York City to Albany in a record time of only thirty-two hours. Soon, a fleet of steamboats was traversing the Hudson River and New York Harbor, later expanding to travel every major American river including the mighty Mississippi. Steamboats could travel faster and more cheaply than sailing vessels or keelboats, which floated downriver and had to be poled or towed upriver on the return voyage. Steamboats also arrived with much greater dependability. The steamboat facilitated the rapid economic development of the massive Mississippi River Valley and the settlement of the West.

This painting of Fulton’s ship, the Clermont, was created by Frederic Leonard King. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Virginia-born Cyrus McCormick wanted to replace the laborious process of using a scythe to cut and gather wheat for harvest. In 1831, he and the enslaved people on his family’s plantation tested a horse-drawn mechanical reaper, and over the next several decades, he made constant improvements to it. More farmers began using it in the 1840s, and greater demand for the McCormick reaper led McCormick and his brother to establish the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company in Chicago, where labor was more readily available. By the 1850s, McCormick’s mechanical reaper had enabled farmers to vastly increase their output. McCormick—and also John Deere, who improved on the design of plows—opened the prairies to agriculture. McCormick’s bigger machine could harvest grain faster, and Deere’s plow could cut through the thick prairie sod. Agriculture north of the Ohio River became the pantry that would lower food prices and feed the major cities in the East. In short order, Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois all become major agricultural states.

Samuel Morse added the telegraph to the list of American innovations introduced in the years before the Civil War. Born in Massachusetts in 1791, Morse first gained renown as a painter before turning his attention to the development of a method of rapid communication in the 1830s. In 1838, he gave the first public demonstration of his method of conveying electric pulses over a wire, using the basis of what became known as Morse code. In 1843, Congress agreed to help fund the new technology by allocating $30,000 for a telegraph line to connect Washington, DC, and Baltimore along the route of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. In 1844, Morse sent the first telegraph message on the new link. Improved communication systems fostered the development of business, economics, and politics by allowing for dissemination of news at a speed previously unknown.

RAILROADS

Starting in the late 1820s, steam locomotives began to compete with horse-drawn carriages. The railroads with steam locomotives offered a new mode of transportation that fascinated citizens, buoying their optimistic view of the possibilities of technological progress. The Mohawk and Hudson Railroad was the first to begin service with a steam locomotive. Its inaugural train ran in 1831 on a track outside Albany and covered twelve miles in twenty-five minutes. Soon it was traveling regularly between Albany and Schenectady.

Toward the middle of the century, railroad construction kicked into high gear, and eager investors quickly formed a number of railroad companies. As a railroad grid began to take shape, it stimulated a greater demand for coal, iron, and steel. Soon, both railroads and canals crisscrossed the states, providing a transportation infrastructure that fueled the growth of American commerce. Indeed, the transportation revolution led to development in the coal, iron, and steel industries, providing many Americans with new job opportunities.

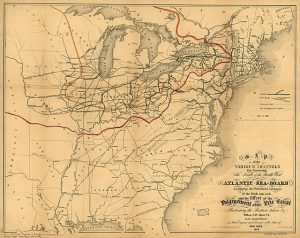

This 1853 map of the eastern half of the United States shows canals, finished railroads, railroads in progress of construction, and proposed lines. Source: Wikimedia Commons

SOCIAL AND CULTURAL IMPACT

The expansion of railroads changed people’s lives. In 1786, it had taken a minimum of four days to travel from Boston, Massachusetts, to Providence, Rhode Island. By 1840, the trip took half a day on a train. In the twenty-first century, this may seem intolerably slow, but people at the time were amazed by the railroad’s speed. Its average of twenty miles per hour was twice as fast as other available modes of transportation.

By 1840, more than three thousand miles of canals had been dug in the United States, and thirty thousand miles of railroad track had been laid by the beginning of the Civil War. These advances in transportation made it easier and less expensive to ship agricultural products from the West to feed people in eastern cities, and to send manufactured goods from the East to people in the West. Without this ability to transport goods, the economic transformation of the 19th century would not have been possible. Rural families also became less isolated as a result of the transportation revolution.

Although the urban working class could not afford the consumer goods that the middle class could, its members did exercise a great deal of influence over popular culture. Theirs was a festive public culture of release and escape from the drudgery of factory work, catered to by the likes of Phineas Taylor Barnum, the celebrated circus promoter and showman. Taverns also served an important function as places to forget the long hours and uncertain wages of the factories.

|

|

AMERICANA |

|

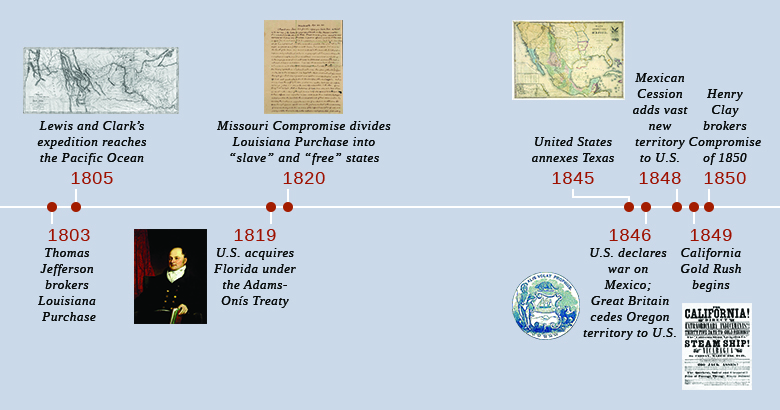

P. T. Barnum and the Feejee Mermaid The Connecticut native P. T. Barnum catered to the demand for escape and cheap amusements among the working class. His American Museum in New York City opened in 1841 and achieved great success. Millions flocked to see Barnum’s exhibits, which included a number of fantastic human and animal oddities, almost all of which were hoaxes. One exhibit in the 1840s featured the “Feejee Mermaid,” which Barnum presented as proof of the existence of the mythical mermaids of the deep. In truth, the mermaid was a half-monkey, half-fish stitched together.

|

|

The profound economic changes sweeping the United States also led to equally important social and cultural transformations. The formation of distinct classes, especially in the rapidly industrializing North, was one of the most striking developments. The unequal distribution of newly created wealth spurred new divisions along class lines. Each class had its own specific culture and views on the issue of slavery.

THE ECONOMIC ELITE

Economic elites gained further social and political ascendance in the United States due to a fast-growing economy that enhanced their wealth and allowed distinctive social and cultural characteristics to develop among different economic groups. In the major northern cities of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, leading merchants formed an industrial capitalist elite. Many came from families that had been deeply engaged in colonial trade in tea, sugar, pepper, slaves, and other commodities and that were familiar with trade networks connecting the United States with Europe, the West Indies, and the Far East. These colonial merchants had passed their wealth to their children.

After the War of 1812, the new generation of merchants expanded their economic activities. They began to specialize in specific types of industry, spearheading the development of industrial capitalism based on factories they owned and on specific commercial services such as banking, insurance, and shipping. Members of the northern business elite forged close ties with each other to protect and expand their economic interests. Marriages between leading families formed a crucial strategy to advance economic advantage, and the homes of the northern elite became important venues for solidifying social bonds. Exclusive neighborhoods started to develop as the wealthy distanced themselves from the poorer urban residents, and cities soon became segregated by class. Many northern elites worked hard to ensure the transmission of their inherited wealth from one generation to the next. Politically, they exercised considerable power in local and state elections. Most had ties to the cotton trade, so they were strong supporters of slavery.

The Industrial Revolution led some former artisans to reinvent themselves as manufacturers. These enterprising leaders of manufacturing differed from the established commercial elite in the North and South because they did not inherit wealth. Instead, many came from very humble working-class origins and embodied the dream of achieving upward social mobility through hard work and discipline. As the beneficiaries of the economic transformations sweeping the republic, these newly established manufacturers formed a new economic elite that thrived in the cities and cultivated its own distinct sensibilities. They created a culture that celebrated hard work, a position that put them at odds with southern planter elites who prized leisure and with other elite northerners who had largely inherited their wealth and status.

THE MIDDLE CLASS

Not all enterprising artisans were so successful that they could rise to the level of the elite. However, many artisans and small merchants, who owned small factories and stores, did manage to achieve and maintain respectability in an emerging middle class. Lacking the protection of great wealth, members of the middle class agonized over the fear that they might slip into the ranks of wage laborers. Thus, they strove to maintain or improve their middle-class status and that of their children.

To this end, the middle class valued cleanliness, discipline, morality, hard work, education, and good manners. Hard work and education enabled them to rise in life. Most members of the middle class thus took a dim view of slavery, however, since it promoted a culture of leisure. Slavery stood as the antithesis of the middle-class view that dignity and respectability were achieved through work, and many members of this class became active in efforts to end it.

Middle-class women did not work for wages. Their job was to care for the children and to keep the house in a state of order and cleanliness. They also performed the important tasks of cultivating good manners among their children and their husbands and of purchasing consumer goods; both activities proclaimed to neighbors and prospective business partners that their families were educated, cultured, and financially successful. Their children, therefore, did not work in factories. Instead, they attended school and in their free time engaged in “self-improving” activities, such as reading or playing the piano, or they played with toys and games that would teach them the skills and values they needed to succeed in life. In the early nineteenth century, members of the middle class began to limit the number of children they had. Children no longer contributed economically to the household and raising them “correctly” required money and attention. It therefore made sense to have fewer of them.

THE WORKING CLASS

The Industrial Revolution in the United States created a new class of wage workers, and this working class also developed its own culture. They formed their own neighborhoods, living away from the oversight of bosses and managers. While industrialization and the market revolution brought some improvements to the lives of the working class, these sweeping changes did not benefit laborers as much as they did the middle class and the elites. The working class continued to live an often-precarious existence. They suffered greatly during economic slumps, such as the Panic of 1819.

Although most working-class men sought to emulate the middle class by keeping their wives and children out of the work force, their economic situation often necessitated that others besides the male head of the family contribute to its support. Thus, working-class children might attend school for a few years or learn to read and write at Sunday school, but education was sacrificed when income was needed, and many working-class children went to work in factories. While the wives of wage laborers usually did not work for wages outside the home, many took in laundry or did piecework at home to supplement the family’s income.

Wage workers in the North were largely hostile to the abolition of slavery, fearing it would unleash more competition for jobs from free blacks. Many were also hostile to immigration. The pace of immigration to the United States accelerated in the 1840s and 1850s as Europeans were drawn to the promise of employment and land in the United States. Many new members of the working class came from the ranks of these immigrants, who brought new foods, customs, and religions. The Roman Catholic population of the United States, fairly small before this period, began to swell with the arrival of the Irish and the Germans.

5.2 Section Summary

The selling of the public domain was one of the key features of the early nineteenth century in the United States. In the wild frenzy of land purchases and speculation in land, state banks advanced risky loans and created unstable paper money not backed by gold or silver, ultimately leading to the Panic of 1819. Recovery came in the 1820s, followed by a period of robust growth. In this age of entrepreneurship, in which those who invested their money wisely in land, business ventures, or technological improvements reaped vast profits, inventors produced new wonders that transformed American life. American investors and the government began building roads, turnpikes, canals, and railroads. The time required to travel shrank vastly, and people marveled at their ability to conquer great distances, enhancing their sense of the steady advance of progress. Finally, the creation of distinctive classes in the North drove striking new cultural developments. Even among the wealthy elites, northern business families, who had mainly inherited their money, distanced themselves from the newly wealthy manufacturing leaders. Regardless of how they had earned their money, however, the elite lived and socialized apart from members of the growing middle class. The middle class valued work, consumption, and education and dedicated their energies to maintaining or advancing their social status. Wage workers formed their own society in industrial cities and mill villages, though lack of money and long working hours effectively prevented the working class from consuming the fruits of their labor, educating their children, or advancing up the economic ladder.

5.3 A New Political Style: From John Quincy Adams to Andrew Jackson

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain and illustrate the new style of American politics in the 1820s

- Describe the policies of John Quincy Adams’s presidency and explain the political divisions that resulted

The economic transformation of the United States in the decades preceding the Civil War was paralleled by significant political changes. In the 1820s, American political culture gave way to the democratic urges of the citizenry. Political leaders and parties rose to popularity by championing the will of the people, pushing the country toward a future in which a wider swath of citizens gained a political voice. However, this expansion of political power was limited to white men; women, free blacks, and Indians remained—or grew increasingly—disenfranchised by the American political system.

THE DECLINE OF FEDERALISM

The first party system in the United States shaped the political contest between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. The Federalists, led by Washington, Hamilton, and Adams, dominated American politics in the 1790s. After the election of Thomas Jefferson—the Revolution of 1800—the Democratic-Republicans gained ascendance. The gradual decline of the Federalist Party is evident in its losses in the presidential contests that occurred between 1800 and 1820. After 1816, in which Democratic-Republican James Monroe defeated his Federalist rival Rufus King, the Federalists never ran another presidential candidate.

Before the 1820s, a code of deference had underwritten the republic’s political order. Deference was the practice of showing respect for individuals who had distinguished themselves through military accomplishments, educational attainment, business success, or family pedigree. Such individuals were members of what many Americans in the early republic agreed was a natural aristocracy. Deference shown to them dovetailed with republicanism and its emphasis on virtue, the ideal of placing the common good above narrow self-interest. Republican statesmen in the 1780s and 1790s expected and routinely received deferential treatment from others, and ordinary Americans deferred to their “social betters” as a matter of course.

“Father, I Can Not Tell a Lie: I Cut the Tree” (1867) by John McRae, after a painting by George Gorgas White, illustrates Mason Locke Weems’s tale of Washington’s honesty and integrity as revealed in the incident of the cherry tree. Although it was fiction, this story about Washington taught generations of children about the importance of virtue. Source: Wikimedia Commons

DEMOCRATIC REFORMS

In the early 1820s, deference to pedigree began to wane in American society. A new type of deference—to the will of the majority and not to a ruling class—took hold. The spirit of democratic reform became most evident in the widespread belief that all white men, regardless of whether they owned property, had the right to participate in elections. Before the 1820s, many state constitutions had imposed property qualifications for voting as a means to keep democratic tendencies in check. However, as Federalist ideals fell out of favor, ordinary men from the middle and lower classes increasingly questioned the idea that property ownership was an indication of virtue. They argued for universal manhood suffrage.

Expanded voting rights did not extend to women, Indians, or free blacks in the North. Indeed, race replaced property qualifications as the criterion for voting rights. American democracy had a decidedly racist orientation; a white majority limited the rights of black minorities. New Jersey explicitly restricted the right to vote to white men only. Connecticut passed a law in 1814 taking the right to vote away from free black men and restricting suffrage to white men only. By the 1820s, 80 percent of the white male population could vote in New York State elections. No other state had expanded suffrage so dramatically. At the same time, however, New York effectively disenfranchised free black men in 1822 (black men had had the right to vote under the 1777 constitution) by requiring that “men of color” must possess property over the value of $250.

PARTY POLITICS AND THE ELECTION OF 1824

In addition to expanding white men’s right to vote, democratic currents also led to a new style of political party organization, most evident in New York State in the years after the War of 1812. Under the leadership of Martin Van Buren, New York’s “Bucktail” Republican faction (so named because members wore a deer’s tail on their hats, a symbol of membership in the Tammany Society) gained political power by cultivating loyalty to the will of the majority, not to an elite family or renowned figure. In this way, Van Buren helped create a political machine of disciplined party members who prized loyalty above all else, a harbinger of future patronage politics in the United States. Van Buren’s political machine helped radically transform New York politics.

Party politics also transformed the national political landscape, and the election of 1824 proved a turning point in American politics. With tens of thousands of new voters, the older system of having members of Congress form congressional caucuses to determine who would run no longer worked. The new voters had regional interests and voted on them. For the first time, the popular vote mattered in a presidential election. Electors were chosen by popular vote in eighteen states, while the six remaining states used the older system in which state legislatures chose electors.

With the caucus system defunct, the presidential election of 1824 featured five candidates, all of whom ran as Democratic-Republicans (the Federalists having ceased to be a national political force). The crowded field included John Quincy Adams, the son of the second president, John Adams. He represented New England. A second candidate, John C. Calhoun from South Carolina, had served as secretary of war and represented the slaveholding South. A third candidate, Henry Clay, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, hailed from Kentucky and represented the western states. He favored an active federal government committed to internal improvements, such as roads and canals, to bolster national economic development and settlement of the West. William H. Crawford, an enslaver from Georgia, suffered a stroke in 1823 that left him largely incapacitated, but he ran nonetheless and had the backing of the New York machine headed by Van Buren. Andrew Jackson, the famed “hero of New Orleans,” rounded out the field. Jackson had very little formal education, but he was popular for his military victories in the War of 1812 and in wars against the Creek and the Seminole. He had been elected to the Senate in 1823, and his popularity soared as pro-Jackson newspapers sang the praises of the courage and daring of the Tennessee enslaver.

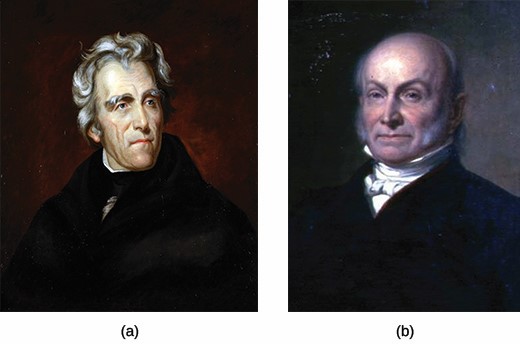

The two most popular presidential candidates in the election of 1824 were Andrew Jackson (a), who won the popular vote but failed to secure the requisite number of votes in the Electoral College, and John Quincy Adams (b), who emerged victorious after a contentious vote in the U.S. House of Representatives. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Results from the eighteen states where the popular vote determined the electoral vote gave Jackson the election. The Electoral College, however, was another matter. Of the 261 electoral votes, Jackson needed 131 or better to win but secured only 99. Because Jackson did not receive a majority vote from the Electoral College, the election was decided following the terms of the Twelfth Amendment, which stipulated that when a candidate did not receive a majority of electoral votes, the election went to the House of Representatives, where each state would provide one vote. House Speaker Clay did not want to see his rival, Jackson, become president and therefore worked within the House to secure the presidency for Adams, convincing many to cast their vote for the New Englander. Clay’s efforts paid off; despite not having won the popular vote, John Quincy Adams was certified by the House as the next president. Jackson and his supporters cried foul. To them, the election of Adams reeked of anti-democratic corruption. So too did the appointment of Clay as secretary of state. John C. Calhoun labeled the whole affair a “corrupt bargain.” Everywhere, Jackson supporters vowed revenge against the antimajoritarian result of 1824.

THE PRESIDENCY OF JOHN QUINCY ADAMS

Adams appointed Henry Clay to be Secretary of State. Clay championed what was known as the American System of high tariffs, a national bank, and federally sponsored internal improvements of canals and roads. Once in office, President Adams embraced Clay’s American System and proposed a national university and naval academy to train future leaders of the republic. The president’s opponents smelled elitism in these proposals and pounced on what they viewed as the administration’s catering to a small, privileged class at the expense of ordinary citizens.

Clay also envisioned a broad range of internal transportation improvements. Using the proceeds from land sales in the West, Adams endorsed the creation of roads and canals to facilitate commerce and the advance of settlement in the West. Many in Congress vigorously opposed federal funding of internal improvements, citing among other reasons that the Constitution did not give the federal government the power to fund these projects. However, in the end, Adams succeeded in extending the Cumberland Road into Ohio (a federal highway project). He also broke ground for the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal on July 4, 1828.

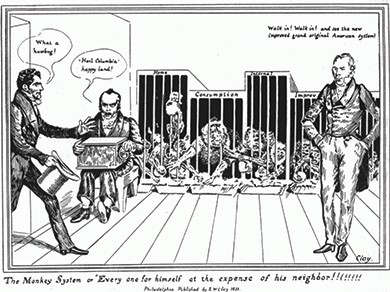

“The Monkey System or ‘Every one for himself at the expense of his neighbor!!!!!!!!’”(1831) critiqued Henry Clay’s proposed tariff and system of internal improvements. In this political cartoon by Edward Williams Clay, four caged monkeys labeled “Home,” “Consumption,” “Internal,” and “Improv” (improvements)—different parts of the nation’s economy—steal each other’s food while Henry Clay, in the foreground, extols the virtues of his “grand original American System.” Source: Wikimedia Commons

President Adams wished to promote manufacturing, especially in his home region of New England. To that end, in 1828 he proposed a high tariff on imported goods, amounting to 50 percent of their value. The tariff raised questions about how power should be distributed, causing a fiery debate between those who supported states’ rights and those who supported the expanded power of the federal government. Those who championed states’ rights denounced the 1828 measure as the Tariff of Abominations, clear evidence that the federal government favored one region, in this case the North, over another, the South. They made their case by pointing out that the North had an expanding manufacturing base while the South did not. Therefore, the South imported far more manufactured goods than the North, causing the tariff to fall most heavily on the southern states.

The 1828 tariff generated additional fears among southerners. In particular, it suggested to them that the federal government would unilaterally take steps that hurt the South. This line of reasoning led some southerners to fear that the very foundation of the South—slavery—could come under attack from a hostile northern majority in Congress. The spokesman for this southern view was President Adams’s vice president, John C. Calhoun.

The crisis over the Tariff of 1828 continued into the 1830s and highlighted one of the currents of democracy in the Age of Jackson: namely, that many southerners believed a democratic majority could be harmful to their interests. These southerners saw themselves as an embattled minority and claimed the right of states to nullify federal laws that appeared to threaten state sovereignty. Another undercurrent was the resentment and anger of the majority against symbols of elite privilege, especially powerful financial institutions like the Second Bank of the United States.

|

|

DEFINING “AMERICAN” |

|

John C. Calhoun on the Tariff of 1828 Vice President John C. Calhoun, angry about the passage of the Tariff of 1828, anonymously wrote a report titled “South Carolina Exposition and Protest” (later known as “Calhoun’s Exposition”) for the South Carolina legislature. As a native of South Carolina, Calhoun articulated the fear among many southerners that the federal government could exercise undue power over the states. If it be conceded, as it must be by everyone who is the least conversant with our institutions, that the sovereign powers delegated are divided between the General and State Governments, and that the latter hold their portion by the same tenure as the former, it would seem impossible to deny to the States the right of deciding on the infractions of their powers, and the proper remedy to be applied for their correction. The right of judging, in such cases, is an essential attribute of sovereignty, of which the States cannot be divested without losing their sovereignty itself, and being reduced to a subordinate corporate condition. In fact, to divide power, and to give to one of the parties the exclusive right of judging of the portion allotted to each, is, in reality, not to divide it at all; and to reserve such exclusive right to the General Government (it matters not by what department) to be exercised, is to convert it, in fact, into a great consolidated government, with unlimited powers, and to divest the States, in reality, of all their rights, It is impossible to understand the force of terms, and to deny so plain a conclusion. —John C. Calhoun, “South Carolina Exposition and Protest,” 1828 |

|

5.3 Section Summary

The early 1800s saw an age of deference give way to universal manhood suffrage and a new type of political organization based on loyalty to the party. The election of 1824 was a fight among Democratic-Republicans that ended up pitting southerner Andrew Jackson against northerner John Quincy Adams. When Adams won through political negotiations in the House of Representatives, Jackson’s supporters derided the election as a “corrupt bargain.” The Tariff of 1828 further stirred southern sentiment, this time against a perceived bias in the federal government toward northeastern manufacturers. At the same time, the tariff stirred deeper fears that the federal government might take steps that could undermine the system of slavery.

5.4 The Rise of American Democracy

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the key points of the election of 1828

- Explain the factors that contributed to the Nullification Crisis

A turning point in American political history occurred in 1828, which witnessed the election of Andrew Jackson over the incumbent John Quincy Adams. While democratic practices had been in ascendance since 1800, the year also saw the further unfolding of a democratic spirit in the United States. Supporters of Jackson called themselves Democrats or the Democracy, giving birth to the Democratic Party. Political authority appeared to rest with the majority as never before.

THE CAMPAIGN AND ELECTION OF 1828

During the 1800s, democratic reforms made steady progress with the abolition of property qualifications for voting and the birth of new forms of political party organization. The 1828 campaign pushed new democratic practices even further and highlighted the difference between the Jacksonian expanded electorate and the older, exclusive Adams style. A slogan of the day, “Adams who can write/Jackson who can fight,” captured the contrast between Adams the aristocrat and Jackson the frontiersman.

The 1828 campaign differed significantly from earlier presidential contests because of the party organization that promoted Andrew Jackson. Jackson and his supporters reminded voters of the “corrupt bargain” of 1824. They framed it as the work of a small group of political elites deciding who would lead the nation, acting in a self-serving manner and ignoring the will of the majority. From Nashville, Tennessee, the Jackson campaign organized supporters around the nation through editorials in partisan newspapers and other publications. Pro-Jackson newspapers heralded the “hero of New Orleans” while denouncing Adams. At the local level, Jackson’s supporters worked to bring in as many new voters as possible. Rallies, parades, and other rituals further broadcast the message that Jackson stood for the common man against the corrupt elite backing Adams and Clay. Democratic organizations called Hickory Clubs, a tribute to Jackson’s nickname, Old Hickory, also worked tirelessly to ensure his election.

In November 1828, Jackson won an overwhelming victory over Adams, capturing 56 percent of the popular vote and 68 percent of the electoral vote. As in 1800, when Jefferson had won over the Federalist incumbent John Adams, the presidency passed to a new political party, the Democrats. The election was the climax of several decades of expanding democracy in the United States and the end of the older politics of deference.

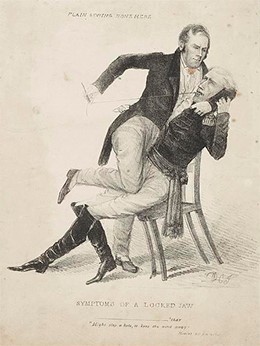

The bitter rivalry between Andrew Jackson and Henry Clay was exacerbated by the “corrupt bargain” of 1824, which Jackson made much of during his successful presidential campaign in 1828. This drawing, published in the 1830s during the debates over the future of the Second Bank of the United States, shows Clay sewing up Jackson’s mouth while the “cure for calumny [slander]” protrudes from his pocket. Source: Wikimedia Commons

LOYALTY ABOVE ALL

Amid revelations of widespread fraud, including the disclosure that some $300,000 was missing from the Treasury Department, Jackson removed almost 50 percent of appointed civil officers, which allowed him to handpick their replacements. Lucrative posts, such as postmaster and deputy postmaster, went to party loyalists, especially in places where Jackson’s support had been weakest, such as New England. Some Democratic newspaper editors who had supported Jackson during the campaign also gained public jobs. In office, Jackson relied on a group of informal advisers that was dubbed the Kitchen Cabinet. This select group of presidential supporters highlights the importance of party loyalty to Jackson and the Democratic Party.

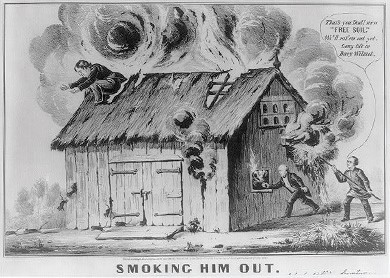

THE NULLIFICATION CRISIS

The Tariff of 1828 had driven Vice President Calhoun to pen his “South Carolina Exposition and Protest,” in which he argued that if a national majority acted against the interest of a regional minority, then individual states could void—or nullify—federal law. By the early 1830s, the battle over the tariff took on new urgency as the price of cotton continued to fall. In 1818, cotton had been thirty-one cents per pound. By 1831, it had sunk to eight cents per pound. While production of cotton had soared during this time and this increase contributed to the decline in prices, many southerners blamed their economic problems squarely on the tariff for raising the prices they had to pay for imported goods while their own income shrank.

Resentment of the tariff was linked directly to the issue of slavery, because the tariff demonstrated the use of federal power. Some southerners feared the federal government would next take additional action against the South, including the abolition of slavery. The theory of nullification, or the voiding of unwelcome federal laws, provided wealthy enslavers, who were a minority in the United States, with an argument for resisting the national government if it acted contrary to their interests. Nullification also raised the specter of secession; aggrieved states at the mercy of an aggressive majority would be forced to leave the Union.

The governor of South Carolina, Robert Hayne, elected in 1832, was a strong proponent of states’ rights and the theory of nullification. Source: Wikimedia Commons

To deal with the crisis, Jackson advocated a reduction in tariff rates. The Tariff of 1832, passed in the summer, lowered the rates on some products like imported goods, a move designed to calm southerners. It did not have the desired effect, however, and Calhoun’s nullifiers still claimed their right to override federal law. In November, South Carolina passed the Ordinance of Nullification, declaring the 1828 and 1832 tariffs null and void. Jackson responded, however, by declaring in the December 1832 Nullification Proclamation that a state did not have the power to void a federal law.

The Nullification Crisis illustrated the growing tensions in American democracy: an aggrieved minority of elite, wealthy slaveholders taking a stand against the will of a democratic majority; an emerging sectional divide between South and North over slavery; and a clash between those who believed in free trade and those who believed in protective tariffs to encourage the nation’s economic growth. These tensions would color the next three decades of politics in the United States.

THE BANK WAR

Congress had established the Bank of the United States in 1791 as a key pillar of Alexander Hamilton’s financial program, but its twenty-year charter expired in 1811. In 1816, Congress approved a new national bank—the Second Bank of the United States. It too had a twenty-year charter, set to expire in 1836. This Second Bank of the United States was created to stabilize the banking system. More than two hundred banks existed in the United States in 1816, and almost all of them issued paper money. In other words, citizens faced a bewildering welter of paper money with no standard value. In fact, the problem of paper money had contributed significantly to the Panic of 1819.

In the 1820s, the national bank moved into a magnificent new building in Philadelphia. However, despite Congress’s approval of the Second Bank of the United States, a great many people continued to view it as tool of the wealthy, an anti-democratic force. President Jackson was among them; he had faced economic crises of his own during his days speculating in land, an experience that had made him uneasy about paper money. To Jackson, hard currency—that is, gold or silver—was the far better alternative. The president also personally disliked the bank’s director, Nicholas Biddle.

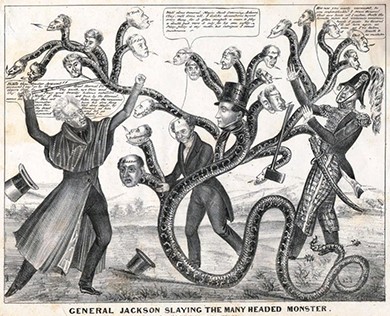

In General Jackson Slaying the Many Headed Monster (1836), the artist, Henry R. Robinson, depicts President Jackson using a cane marked “Veto” to battle a many-headed snake representing state banks, which supported the national bank. Battling alongside Martin Van Buren and Jack Downing, Jackson addresses the largest head, that of Nicholas Biddle, the director of the national bank: “Biddle thou Monster Avaunt [go away]!! . . .” Source: Wikimedia Commons

In the reelection campaign of 1832, Jackson’s opponents in Congress, including Henry Clay, hoped to use their support of the bank to their advantage. In January 1832, they pushed for legislation that would re-charter it, even though its charter was not scheduled to expire until 1836. When the bill for re-chartering passed and came to President Jackson, he used his executive authority to veto the measure. The defeat of the Second Bank of the United States demonstrates Jackson’s ability to focus on the specific issues that aroused the democratic majority. Jackson understood people’s anger and distrust toward the bank, which stood as an emblem of special privilege and big government. He skillfully used that perception to his advantage, presenting the bank issue as a struggle of ordinary people against a rapacious elite class who cared nothing for the public and pursued only their own selfish ends. As Jackson portrayed it, his was a battle for small government and ordinary Americans.

WHIGS

Jackson’s veto of the bank helped galvanize opposition forces into a new political party, the Whigs, a faction that began to form in 1834. The name was significant; opponents of Jackson saw him as exercising tyrannical power, so they chose the name Whig after the eighteenth-century political party that resisted the monarchical power of King George III. One political cartoon dubbed the president “King Andrew the First” and displayed Jackson standing on the Constitution, which has been ripped to shreds. Whigs championed an active federal government committed to internal improvements, including a national bank.

5.4 Section Summary

The Democratic-Republicans’ “corrupt bargain” that brought John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay to office in 1824 also helped to push them out of office in 1828. Jackson used it to highlight the cronyism of Washington politics. Supporters presented him as a true man of the people fighting against the elitism of Clay and Adams. Jackson rode a wave of populist fervor all the way to the White House, ushering in the ascendency of a new political party: the Democrats. Although Jackson ran on a platform of clearing the corruption out of Washington, he rewarded his own loyal followers with plum government jobs, thus continuing and intensifying the cycle of favoritism and corruption.

Andrew Jackson’s election in 1832 signaled the rise of the Democratic Party and a new style of American politics. Jackson understood the views of the majority, and he skillfully used the popular will to his advantage. He adroitly navigated through the Nullification Crisis. His actions, however, stimulated opponents to fashion an opposition party, the Whigs.

5.5 Indian Removal

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the legal wrangling that surrounded the Indian Removal Act

- Describe how depictions of Indians in popular culture helped lead to Indian removal

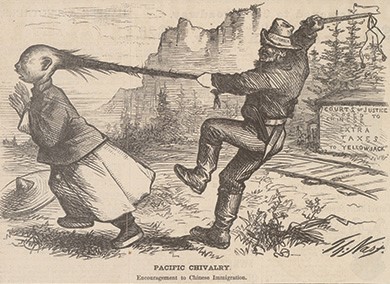

Pro-Jackson newspapers touted the president as a champion of opening land for white settlement and moving native inhabitants beyond the boundaries of “American civilization.” In this effort, Jackson reflected majority opinion: most Americans believed Indians had no place in the white republic. Jackson’s animosity toward Indians ran deep. He had fought against the Creek in 1813 and against the Seminole in 1817, and his reputation and popularity rested in large measure on his firm commitment to remove Indians from states in the South. The 1830 Indian Removal Act and subsequent displacement of the Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Cherokee tribes of the Southeast fulfilled the vision of a white nation and became one of the identifying characteristics of the Age of Jackson.

THE INDIAN REMOVAL ACT

Popular culture in the first half of the nineteenth century reflected the aversion to Indians that was pervasive during the Age of Jackson. Jackson skillfully played upon this racial hatred to engage the United States in a policy of ethnic cleansing, eradicating the Indian presence from the land to make way for white civilization. In an age of mass democracy, powerful anti-Indian sentiments found expression in mass culture, shaping popular perceptions.

|

|

AMERICANA |

|

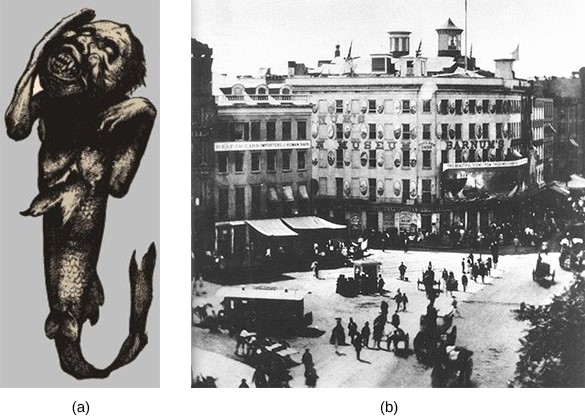

The Paintings of George Catlin The 19th century painter George Catlin seized upon the public fascination with the supposedly exotic and savage Indian, seeing an opportunity to make money by painting them in a way that conformed to popular white stereotypes. In the late 1830s, he toured major cities with his Indian Gallery, a collection of paintings of native peoples. Catlin routinely painted Indians in a supposedly aboriginal state. In Attacking the Grizzly Bear, the hunters do not have rifles and instead rely on spears. Such a portrayal stretches credibility as native peoples had long been exposed to and adopted European weapons. Indeed, the painting’s depiction of Indians riding horses, which were introduced by the Spanish, makes clear that, as much as Catlin and white viewers wanted to believe in the primitive and savage native, the reality was otherwise.

|

|

In his first message to Congress, Jackson had proclaimed that Indian groups living independently within states, as sovereign entities, presented a major problem for state sovereignty. This message referred directly to the situation in Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama, where the Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, and Cherokee peoples stood as obstacles to white settlement. These groups were known as the Five Civilized Tribes, because they had largely adopted Anglo-American culture, speaking English and practicing Christianity. Some held slaves like their white counterparts.

Whites especially resented the Cherokee in Georgia, coveting the tribe’s rich agricultural lands in the northern part of the state. The impulse to remove the Cherokee only increased when gold was discovered on their lands. Ironically, while whites insisted the Cherokee and other native peoples could never be good citizens because of their savage ways, the Cherokee had arguably gone farther than any other indigenous group in adopting white culture. The Cherokee Phoenix, the newspaper of the Cherokee, began publication in 1828 in English and the Cherokee language. Although the Cherokee followed the lead of their white neighbors by farming and owning property, as well as embracing Christianity and owning their own slaves, this proved of little consequence in an era when whites perceived all Indians as incapable of becoming full citizens of the republic.

Jackson’s anti-Indian stance struck a chord with a majority of white citizens, many of whom shared a hatred of nonwhites that spurred Congress to pass the 1830 Indian Removal Act. The act called for the removal of the Five Civilized Tribes from their home in the southeastern United States to land in the West, in present-day Oklahoma.

The Cherokee decided to fight the federal law, however, and took their case to the Supreme Court. This legal struggle—Worcester v. Georgia—asserted the rights of non-natives to live on Indian lands. Samuel Worcester was a Christian missionary and federal postmaster of New Echota, the capital of the Cherokee nation. A Congregationalist, he had gone to live among the Cherokee in Georgia to further the spread of Christianity, and he strongly opposed Indian removal. By living among the Cherokee, Worcester had violated a Georgia law forbidding whites, unless they were agents of the federal government, to live in Indian territory. Worcester was arrested, but because his federal job as postmaster gave him the right to live there, he was released. Jackson supporters then succeeded in taking away Worcester’s job, and he was re-arrested. This time, a court sentenced him and nine others for violating the Georgia state law banning whites from living on Indian land. Worcester was sentenced to four years of hard labor. When the case of Worcester v. Georgia came before the Supreme Court in 1832, Chief Justice John Marshall ruled in favor of Worcester, finding that the Cherokee constituted “distinct political communities” with sovereign rights to their own territory.

|

|

DEFINING “AMERICAN” |

|

Chief Justice John Marshall’s Ruling in Worcester v. Georgia In 1832, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Marshall ruled in favor of Samuel Worcester in Worcester v. Georgia. In doing so, he established the principle of tribal sovereignty. Although this judgment contradicted Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, it failed to halt the Indian Removal Act. In his opinion, Marshall wrote the following: From the commencement of our government Congress has passed acts to regulate trade and intercourse with the Indians; which treat them as nations, respect their rights, and manifest a firm purpose to afford that protection which treaties stipulate. All these acts, and especially that of 1802, which is still in force, manifestly consider the several Indian nations as distinct political communities, having territorial boundaries, within which their authority is exclusive, and having a right to all the lands within those boundaries, which is not only acknowledged, but guaranteed by the United States. . . . The Cherokee Nation, then, is a distinct community, occupying its own territory, with boundaries accurately described, in which the laws of Georgia can have no force, and which the citizens of Georgia have no right to enter but with the assent of the Cherokees themselves or in conformity with treaties and with the acts of Congress. The whole intercourse between the United States and this nation is, by our Constitution and laws, vested in the government of the United States. The act of the State of Georgia under which the plaintiff in error was prosecuted is consequently void, and the judgment a nullity. . . . The Acts of Georgia are repugnant to the Constitution, laws, and treaties of the United States. |

|

The Supreme Court did not have the power to enforce its ruling in Worcester v. Georgia, however, and it became clear that the Cherokee would be compelled to move. Those who understood that the only option was removal traveled west, but the majority stayed on their land. In order to remove them, the president relied on the U.S. military. In a series of forced marches, some fifteen thousand Cherokee were finally relocated to Oklahoma. This forced migration, known as the Trail of Tears, caused the deaths of as many as four thousand Cherokee. The Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole peoples were also compelled to go. The removal of the Five Civilized Tribes provides an example of the power of majority opinion in a democracy.

To some observers, the rise of democracy in the United States raised troubling questions about the new power of the majority to silence minority opinion. As the will of the majority became the rule of the day, everyone outside of mainstream, white American opinion, especially Indians and blacks, were vulnerable to the wrath of the majority. Some worried that the rights of those who opposed the will of the majority would never be safe. Mass democracy also shaped political campaigns as never before. The 1840 presidential election marked a significant turning point in the evolving style of American democratic politics.

The nine figures in this exhibit represent the variety of lifestyles and people that made this historic trek. The exhibit can be viwed at the Cherokee Heritage Center in Oklahoma. Source: Wikipedia Commons

THE 1840 ELECTION

The presidential election contest of 1840 marked the culmination of the democratic revolution that swept the United States. By this time, the second party system had taken hold, a system whereby the older Federalist and Democratic-Republican Parties had been replaced by the new Democratic and Whig Parties. Both Whigs and Democrats jockeyed for election victories and commanded the steady loyalty of political partisans. Voter turnout increased dramatically under the two-party system. Roughly 25 percent of eligible voters cast ballots in 1828. By 1840, voter participation surged to nearly 80 percent.

The differences between the parties were largely about economic policies. Whigs advocated accelerated economic growth, often endorsing federal government projects to achieve that goal. Democrats did not view the federal government as an engine promoting economic growth and advocated a smaller role for the national government. The membership of the parties also differed: Whigs tended to be wealthier; they were prominent planters in the South and wealthy urban northerners. Democrats presented themselves as defenders of the common people against the elite.

In the 1840 presidential campaign, taking their cue from the Democrats who had lionized Jackson’s military accomplishments, the Whigs promoted William Henry Harrison as a war hero based on his 1811 military service against the Shawnee chief Tecumseh at the Battle of Tippecanoe. John Tyler of Virginia ran as the vice-presidential candidate, leading the Whigs to trumpet, “Tippecanoe and Tyler too!” as a campaign slogan.

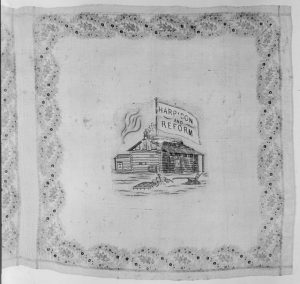

The campaign thrust Harrison into the national spotlight. Democrats tried to discredit him by declaring, “Give him a barrel of hard [alcoholic] cider and settle a pension of two thousand a year on him, and take my word for it, he will sit the remainder of his days in his log cabin.” The Whigs turned the slur to their advantage by presenting Harrison as a man of the people who had been born in a log cabin (in fact, he came from a privileged background in Virginia), and the contest became known as the log cabin campaign.

The Whigs’ efforts, combined with their strategy of blaming Democrats for the lingering economic collapse that began with the hard-currency Panic of 1837, succeeded in carrying the day. A mass campaign with political rallies and party mobilization had molded a candidate to fit an ideal palatable to a majority of American voters, and in 1840 Harrison won what many consider the first modern election.

This 1840 handkerchief in favor of the Democratic Candidate shows a flag bearing the words “Harrison and Reform” flying over a log cabin. Source: Wikimedia Commons

5.5 Section Summary

Popular culture in the Age of Jackson emphasized the savagery of the native peoples and shaped domestic policy. Popular animosity found expression in the Indian Removal Act. Even the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in favor of the Cherokee in Georgia offered no protection against the forced removal of the Five Civilized Tribes from the Southeast, mandated by the 1830 Indian Removal Act and carried out by the U.S. military. The removal of Native Americans from the Southeast reflected the rise of democracy. The majority exercised a new type of power that went well beyond politics. Very quickly, politicians among the Whigs and Democrats learned to master the magic of the many by presenting candidates and policies that catered to the will of the majority. In the 1840 “log cabin campaign,” both sides engaged in the new democratic electioneering. The uninhibited expression during the campaign inaugurated a new political style.

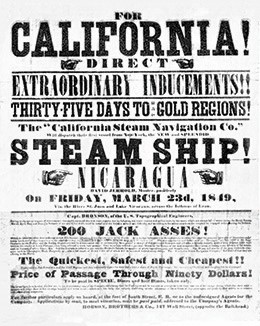

5.6 American Expansion

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the significance of the Louisiana Purchase for American expansionism

- Explain why American settlers in Texas sought independence from Mexico

- Describe the concept of “Manifest Destiny” and the stages of American Expansion in the West

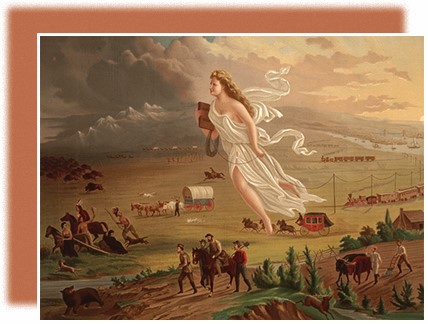

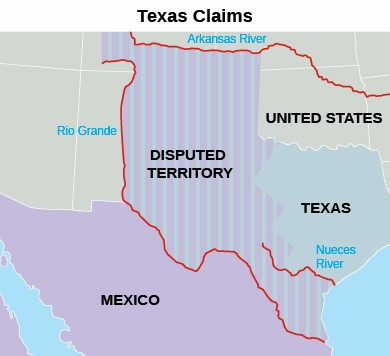

The economic and political changes of the 19th century helped to instill a confident “we can do this” attitude in Americans. This attitude is revealed clearly in John Gast’s painting, American Progress. In this painting, the white, blonde figure of Columbia—a historical personification of the United States—strides triumphantly westward with the Star of Empire on her head. She brings education, symbolized by the schoolbook, and modern technology, represented by the telegraph wire. White settlers follow her lead, driving the helpless natives away and bringing successive waves of technological progress in their wake. In the first half of the nineteenth century, the quest for control of the West led to the Louisiana Purchase, the annexation of Texas, and the Mexican American War. Efforts to seize western territories from native peoples and expand the republic by warring with Mexico “succeeded” beyond expectations. Few nations ever expanded so quickly. Yet, this expansion led to debates about the fate of slavery in the West, creating tensions between North and South that ultimately led to the collapse of American democracy and a brutal civil war.

In the first half of the nineteenth century, settlers began to move west of the Mississippi River in large numbers. In John Gast’s American Progress (ca. 1872), the figure of Columbia, representing the United States and the spirit of democracy, makes her way westward, literally bringing light to the darkness as she advances. Source: Wikimedia Commons

FIRST STAGES OF EXPANSION

The possibilities of expanding the country to the West began with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. When the purchase was complete, President Jefferson was determined to assess its potential for commercial exploitation and to exert U.S. control over the territory. He enlisted Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to lead an expedition through the newly purchased territory. The men traveled across the North American continent and established relationships with many Indian tribes, paving the way for fur traders like John Jacob Astor who later established trading posts solidifying U.S. claims to Oregon. Hundreds of plant and animal specimens were collected, several of which were named for Lewis and Clark in recognition of their efforts. And the territory was more accurately mapped and legally claimed by the United States.

Another stage of U.S. expansion took place when inhabitants of Missouri began petitioning for statehood beginning in 1817. The Missouri territory had been part of the Louisiana Purchase and was the first part of that vast acquisition to apply for statehood. By 1818, tens of thousands of settlers had flocked to Missouri, including enslavers who brought with them some ten thousand enslaved people. When the status of the Missouri territory was taken up in earnest in the U.S. House of Representatives in early 1819, its admission to the Union proved to be no easy matter, since it brought to the surface a violent debate over whether slavery would be allowed in the new state.

Congress finally came to an agreement, called the Missouri Compromise, in 1820. Missouri and Maine (which had been part of Massachusetts) would enter the Union at the same time, Maine as a free state, Missouri as a slave state. The Tallmadge Amendment was narrowly rejected, the balance between free and slave states was maintained in the Senate, and southerners did not have to fear that Missouri slaveholders would be deprived of their human property. To prevent similar conflicts each time a territory applied for statehood, a line coinciding with the southern border of Missouri (at latitude 36° 30′) was drawn across the remainder of the Louisiana Territory. Slavery could exist south of this line but was forbidden north of it, with the obvious exception of Missouri.

The Missouri Compromise resulted in the District of Maine, which had originally been settled in 1607 by the Plymouth Company and was a part of Massachusetts, being admitted to the Union as a free state and Missouri being admitted as a slave state. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Missouri Compromise resulted in the District of Maine, which had originally been settled in 1607 by the Plymouth Company and was a part of Massachusetts, being admitted to the Union as a free state and Missouri being admitted as a slave state. Source: Wikimedia Commons