1 Chapter 1: The Beginnings: Native Americans, Europeans, and Africans to 1650

The Beginnings: Native Americans, Europeans, and Africans to 1650

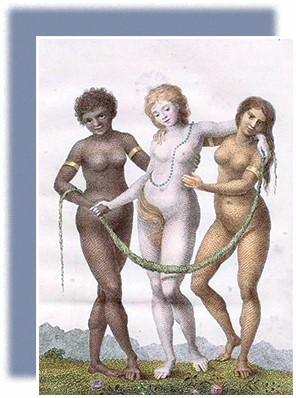

This painting is entitled, “In Europe supported by Africa and America.” Painted in 1796 by artist William Blake, who was an abolitionist, it depicts the interdependence of the three continents in the Atlantic World. The gold armbands on the Indian and African women symbolizes their subjugation. The straw binding the three may represent tobacco. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Chapter 1 Outline

Introduction, Watch and Learn, Questions to Guide your Reading

1.2 Portuguese Exploration and Spanish Conquest

1.3 Challenges to Spain’s Supremacy

1.4 Enforced Labor, Commerce, and the Columbian Exchange

Summary Timelines, Self-Test, Key Term Crossword Puzzle

Introduction

Globalization, the ever-increasing interconnectedness of the world, is not a new phenomenon, but it accelerated when western Europeans discovered the riches of the East. During the Crusades (1095–1291), Europeans developed an appetite for spices, silk, porcelain, sugar, and other luxury items from the East, for which they traded fur, timber, and the Slavic people they captured and sold (hence the word slave). But when the Silk Road, the long overland trading route from China to the Mediterranean, became costlier and more dangerous to travel, Europeans searched for a more efficient and inexpensive trade route over water, initiating the development of what we now call the Atlantic World. In pursuit of commerce in Asia, fifteenth-century traders unexpectedly encountered the “Americas” populated by millions and home to sophisticated and numerous peoples. Mistakenly believing they had reached the East Indies, these early explorers called its inhabitants Indians. West Africa, a diverse and culturally rich area, soon entered the stage as other nations exploited its slave trade and brought its peoples to the Americas in chains. Although Europeans would come to dominate the Americas, they could not have done so without Africans and native peoples.

The story of the Atlantic World is thus the story of global migration, a migration driven in large part by the actions and aspirations of the ruling heads of Europe. Christopher Columbus’ journey in 1492 sparked new rivalries among European powers as they scrambled to create American colonies, fueled by the quest for wealth and power as well as by religious passions. Almost continuous war resulted. Spain achieved early preeminence, creating a far-flung empire, and growing rich with treasures from the Americas. Native Americans who confronted the newcomers from Europe suffered unprecedented losses of life, however, as previously unknown diseases sliced through their populations. They also were victims of the arrogance of the Europeans, who viewed themselves as uncontested masters of the Americas, sent by God to bring Christianity to the “Indians.”

Watch and Learn (Crash Course History videos for chapter 1)

- The Black Legend, Native Americans, and Spaniards

- The Columbian Exchange (part 1)

- The Columbian Exchange (part 2)

- The Transatlantic Slave Trade

Questions to Guide Your Reading

- The Inca were able to control an empire that stretched from modern Colombia to southern Chile. Which of their various means for achieving such control do you think were most effective, and why?

- How did the Olmec, Aztec, Inca, Maya, and North American Indians differ in their ways of life and cultural achievements? How did their particular circumstances—geography, history, or the accomplishments of the societies that had preceded them, for example—serve to shape their particular traditions and cultures?

- What types of labor systems were used in the Americas? Did systems of unfree labor serve more than an economic function?

- What is meant by the Columbian Exchange? Who was affected the most by the exchange?

- What were the various goals of the colonial European powers in the expansion of their empires? To what extent were they able to achieve these goals? Where did they fail?

- On the whole, what was the impact of early European explorations on the Americas? What was the impact of the Americas on Europeans?

1.1 The First Americans

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Locate on a map the major American civilizations before the arrival of the Spanish

- Discuss the cultural achievements of these civilizations

- Discuss the differences and similarities between lifestyles, religious practices, and customs among the native peoples of the Americas

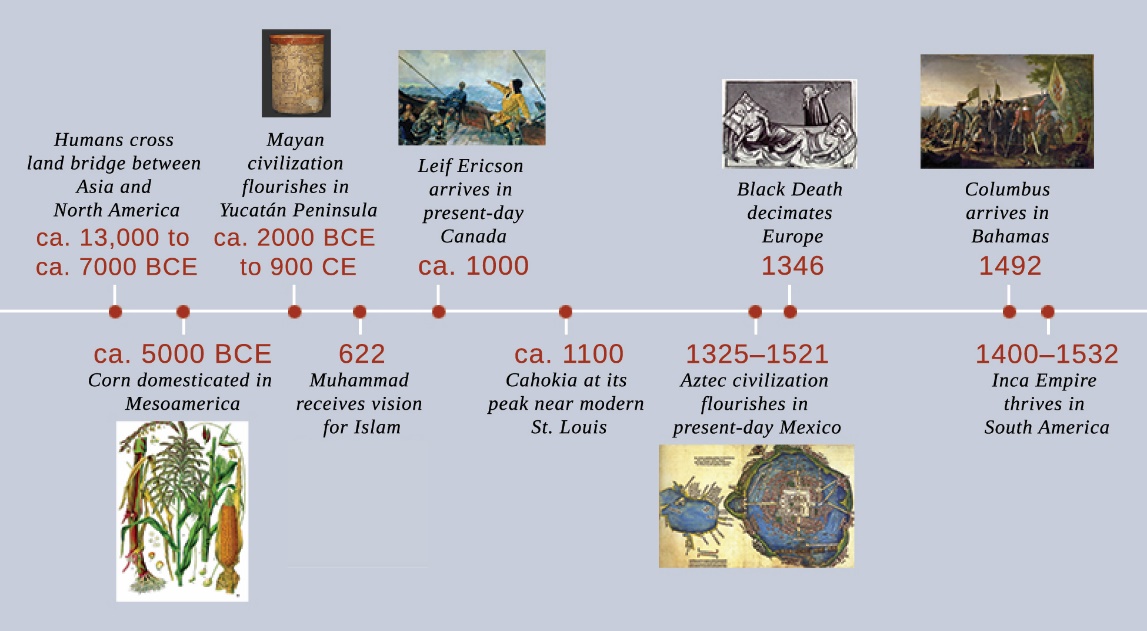

Between nine and fifteen thousand years ago, scholars believe that a land bridge existed between Asia and North America that we now call Beringia. The first inhabitants of what would be named the Americas migrated across this bridge in search of food. When the glaciers melted, water engulfed Beringia, and the Bering Strait was formed. Later settlers came by boat across the narrow strait. Continually moving southward, the settlers eventually populated both North and South America, creating unique cultures that ranged from the highly complex and urban Aztec civilization in what is now Mexico City to the woodland peoples of eastern North America.

About ten thousand years ago, humans also began the domestication of plants and animals, adding agriculture as a means of sustenance to hunting and gathering techniques. With this agricultural revolution, and the more abundant and reliable food supplies it brought, populations grew, and people were able to develop a more settled way of life, building permanent settlements.

THE “MOTHER” CIVILIZATION: THE OLMEC

Mesoamerica is the geographic area stretching from north of Panama up to the desert of central Mexico. Although marked by great topographic, linguistic, and cultural diversity, this region cradled a number of civilizations with similar characteristics. Mesoamericans developed a mathematical system, built huge edifices, and devised a calendar that accurately predicted eclipses and solstices and that priest-astronomers used to direct the planting and harvesting of crops. Most important for our knowledge of these peoples, they created the only known written language in the Western Hemisphere. Though the area had no overarching political structure, trade over long distances helped diffuse culture. Weapons made of obsidian, jewelry crafted from jade, feathers woven into clothing and ornaments, and cacao beans that were whipped into a chocolate drink formed the basis of commerce. The mother of Mesoamerican cultures was the Olmec civilization.

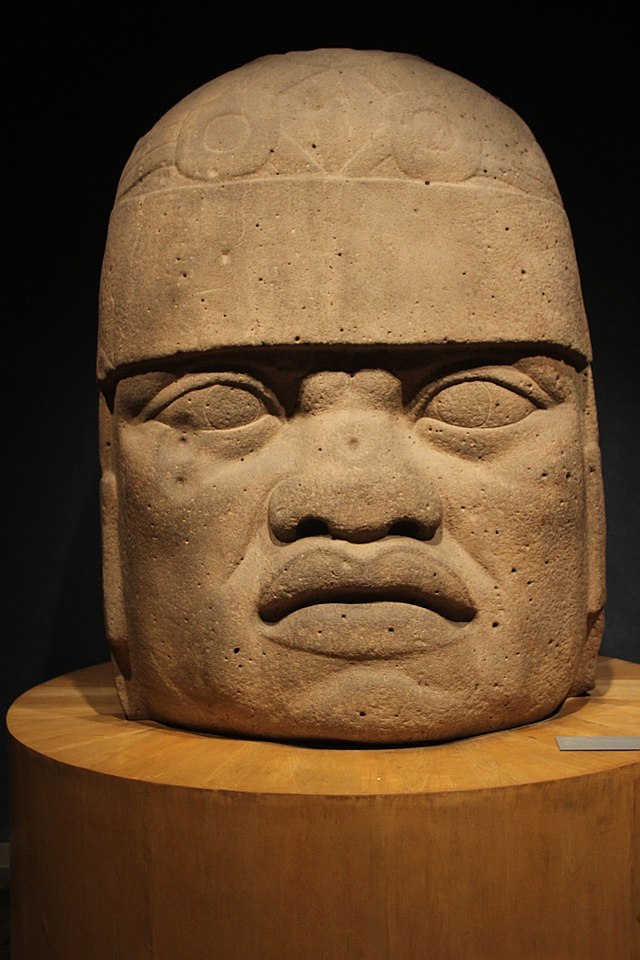

Flourishing along the hot Gulf Coast of Mexico from about 1200 to about 400 BCE, the Olmec produced a number of major works of art, architecture, pottery, and sculpture. Most recognizable are their giant head sculptures and the pyramid in La Venta. The Olmec built aqueducts to transport water into their cities and irrigate their fields. They grew maize, squash, beans, and tomatoes. They also bred small, domesticated dogs which, along with fish, provided their protein. Although no one knows what happened to the Olmec after about 400 BCE, in part because the jungle reclaimed many of their cities, their culture was the base upon which the Maya and the Aztec built. It was the Olmec who worshipped a rain god, a maize god, and the feathered serpent so important in the future pantheons of the Aztecs (who called him Quetzalcoatl) and the Maya (to whom he was Kukulkan). The Olmec also developed a system of trade throughout Mesoamerica, giving rise to an elite class.

The Olmec carved heads from giant boulders that ranged from four to eleven feet in height and could weigh up to fifty tons. This head is preserved in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. Source: Wikimedia Commons

THE MAYA

After the decline of the Olmec, a city rose in the fertile central highlands of Mesoamerica. One of the largest population centers in pre-Columbian America and home to more than 100,000 people at its height in about 500 CE, Teotihuacan was located about thirty miles northeast of modern Mexico City. Large-scale agriculture and the resultant abundance of food allowed time for people to develop special trades and skills other than farming. Builders constructed over twenty-two hundred apartment compounds for multiple families, as well as more than a hundred temples. Among these were the Pyramid of the Sun (which is two hundred feet high) and the Pyramid of the Moon (one hundred and fifty feet high). The city was also the center for trade, which extended to settlements on Mesoamerica’s Gulf Coast.

The Maya were one Mesoamerican culture that had strong ties to Teotihuacan. The Maya’s architectural and mathematical contributions were significant. Flourishing from roughly 2000 BCE to 900 CE in what is now Mexico, Belize, Honduras, and Guatemala, the Maya perfected the calendar and written language the Olmec had begun. They devised a written mathematical system to record crop yields and the size of the population, and to assist in trade. Surrounded by farms relying on primitive agriculture, they built the city-states of Copan, Tikal, and Chichen Itza along their major trade routes, as well as temples, statues of gods, pyramids, and astronomical observatories. However, because of poor soil and a drought that lasted nearly two centuries, their civilization declined by about 900 CE, and they abandoned their large population centers.

El Castillo, located at Chichen Itza in the eastern Yucatán peninsula, served as a temple for the god Kukulkan. Each side contains ninety-one steps to the top. When counting the top platform, the total number of stairs is three hundred and sixty-five, the number of days in a year. Source: Wikimedia Commons

THE AZTEC

According to legend, a warlike people called the Aztec (also known as the Mexica) had left a city called Aztlán and traveled south to the site of present-day Mexico City. In 1325, they began construction of Tenochtitlán on an island in Lake Texcoco. By 1519, this settlement contained upwards of 200,000 inhabitants and was certainly the largest city in the Western Hemisphere at that time and probably larger than any European city. Bernal Díaz del Castillo, one of the first Europeans to visit this city, recorded his impressions upon first seeing it: “When we saw so many cities and villages built in the water and other great towns on dry land we were amazed and said it was like the enchantments . . . on account of the great towers and cues and buildings rising from the water, and all built of masonry. And some of our soldiers even asked whether the things that we saw were not a dream? . . . I do not know how to describe it, seeing things as we did that had never been heard of or seen before, not even dreamed about.”

Tenochtitlán was well planned, clean, and orderly. The city had neighborhoods for specific occupations, a trash collection system, markets, two aqueducts bringing in fresh water, and public buildings and temples. Aztecs bathed daily, and some wealthy homes even contained a steam bath. A labor force of enslaved people from subjugated neighboring communities built the fabulous city and the three causeways that connected it to the mainland. To farm, the Aztec constructed barges made of reeds and filled them with fertile soil. Lake water constantly irrigated these chinampas, or “floating gardens,” which are still in use and can be seen today in Xochimilco, a district of Mexico City.

Each god in the Aztec pantheon represented and ruled an aspect of the natural world, such as the heavens, farming, rain, fertility, sacrifice, and combat. A ruling class of warrior nobles and priests performed ritual human sacrifice daily to sustain the sun on its long journey across the sky, to appease or feed the gods, and to stimulate agricultural production. The sacrificial ceremony included cutting open the chest of a criminal or captured warrior with an obsidian knife and removing the still-beating heart.

In this 16th century illustration, an Aztec priest cuts out the beating heart of a sacrificial victim. Aztec belief centered on supplying the gods with human blood—the ultimate sacrifice—to keep them strong and well. Source: Wikimedia Commons

THE INCA

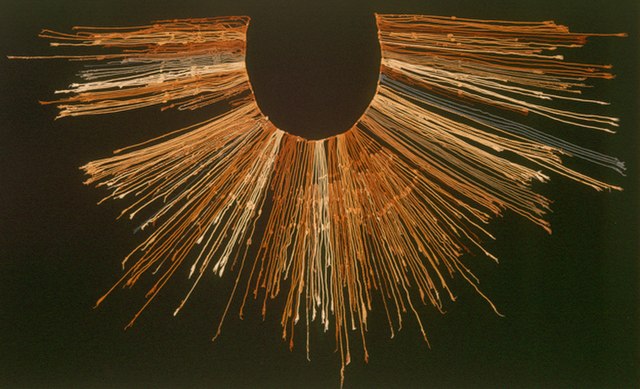

In South America, the most highly developed and complex society was that of the Inca, whose name means “lord” or “ruler” in the Andean language called Quechua. At its height in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Inca Empire, located on the Pacific coast and straddling the Andes Mountains, extended approximately twenty-five hundred miles. It stretched from modern-day Colombia in the north to Chile in the south and included cities built at an altitude of 14,000 feet above sea level. The Inca maintained an elaborate road system which they kept free of debris and which was repaired by workers stationed at varying intervals. The Inca, like all other pre-Columbian societies, did not use axle-mounted wheels for transportation. They built stepped roads to ascend and descend the steep slopes of the Andes. These roads enabled the rapid movement of the highly trained Incan army. The Inca were effective administrators. Runners called chasquis traversed the roads in a continuous relay system, ensuring quick communication over long distances. The Inca had no system of writing, however. They communicated and kept records using a system of colored strings and knots called the quipu (as depicted in the image below).

The Incan ruling class lived off the labor of the peasants, collecting vast wealth that accompanied them as they went, mummified, into the next life. The Inca farmed corn, beans, squash, quinoa (a grain cultivated for its seeds), and the indigenous potato on terraced land they hacked from the steep mountains. Peasants received only one-third of their crops for themselves. The Inca ruler required a third, and a third was set aside in a kind of welfare system for those unable to work. Huge storehouses were filled with food for times of need. Each peasant also worked for the Inca ruler a number of days per month on public works projects, a requirement known as the mita. The Inca worshipped the sun god Inti and called gold the “sweat” of the sun. Unlike the Maya and the Aztecs, they rarely practiced human sacrifice and usually offered the gods food, clothing, and coca leaves.

NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS

Unlike the highly centralized civilizations of the Maya, Aztec, and Inca, the North American Indigenous cultures were more widely dispersed, with each group adapting to the unique environments they inhabited. While these societies did not share the same large population sizes or highly organized social structures, they demonstrated incredible resilience and adaptability. Many Indigenous peoples in North America relied on hunting, fishing, and gathering, alongside the cultivation of crops like corn, beans, and squash, showcasing a diverse approach to food production. The agricultural practices they developed were highly sophisticated, with many communities using innovative techniques suited to their specific landscapes. Indigenous cultures were also rich in tradition and social organization, often with systems of governance that prioritized consensus and balance. These societies, though different from those of Mesoamerica, had complex and thriving cultures that were deeply connected to their environments.

INDIANS OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST AND ALASKA

The Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest and Alaska developed unique cultures that were deeply intertwined with the rich resources of the region. In contrast to many other North American cultures, these societies did not rely heavily on agriculture. Instead, they made full use of the abundant natural resources around them, particularly the forests, rivers, and oceans. Salmon fishing was a central part of life, and many communities built complex systems for harvesting and preserving fish, which provided a reliable food source throughout the year. The people of this region also gathered a variety of plants, such as berries, roots, and seaweed, and hunted game like deer, seals, and whales. The abundance of food allowed these cultures to focus on other aspects of life, such as the creation of impressive art, the development of complex social hierarchies, and the construction of permanent settlements.

In societies such as the Haida, Tlingit, Chinook, and Coast Salish, social status and wealth were determined by the possession of resources, especially through the practice of potlatch ceremonies, where leaders distributed wealth to solidify their status. These cultures also placed a great emphasis on oral history, passing down stories, traditions, and laws through generations. Their art, including totem poles, masks, and woven baskets, reflected both their spiritual beliefs and their deep connection to the natural world. The people of this region developed advanced tools and technologies, such as canoes and fish traps, which allowed them to thrive in a challenging environment. This sustainable way of life, centered around the careful management of resources, shaped the identities and cultures of the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest and Alaska.

INDIANS OF THE CALIFORNIA COAST

The California Coast was home to a remarkably diverse range of Indigenous peoples, with the largest concentration of Native communities in North America living in what is now California. The region’s wealth of natural resources—ranging from the ocean’s bounty to the fertile valleys and abundant forests—allowed its inhabitants to develop a wide array of distinct cultures and ways of life. Indigenous groups in this region, such as the Chumash, Pomo, Ohlone, and Yurok, thrived through a combination of fishing, hunting, and gathering. The ocean provided them with a steady supply of fish and shellfish, while inland communities harvested acorns, seeds, and roots, which formed the staple of their diet. The mild climate and abundant plant life supported a healthy, sustainable lifestyle, which allowed for settled communities that could focus on arts, crafts, and social organization.

Unlike societies in other parts of North America, where agriculture played a more central role, many coastal groups in California did not rely on farming. Instead, they cultivated a deep knowledge of their environment and developed sophisticated techniques for harvesting and processing their food, particularly acorns. These peoples lived in permanent villages, with homes made of reeds or wood, and had a rich cultural life filled with storytelling, ceremonial dances, and art. The Chumash, for example, were known for their skillful basket weaving and the production of intricate sea-shell jewelry. Social organization was typically based on kinship groups, and many communities practiced elaborate rituals, including dances and ceremonies that celebrated the natural world and its cycles. The people of the California Coast enjoyed a varied and thriving existence, with a deep respect for the land and its resources, ensuring their cultures persisted for thousands of years.

INDIANS OF THE AMERICAN SOUTHWEST

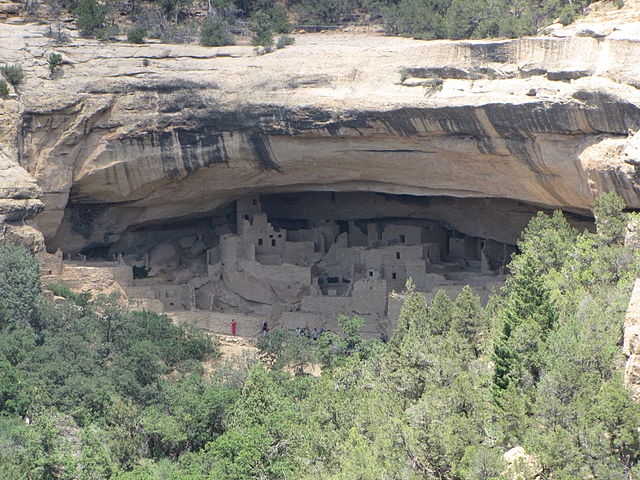

Several groups we collectively call the Pueblo lived in the southwestern part of today’s United States. The Spanish first gave them this name, which means “town” or “village,” because they lived in towns or villages of permanent stone-and-mud buildings with thatched roofs. Like present-day apartment houses, these buildings had multiple stories, each with multiple rooms. The three main groups of the Pueblo people were the Mogollon, Hohokam, and Anasazi.

The Mogollon thrived in the Mimbres Valley (New Mexico) from about 150 BCE to 1450 CE. They developed a distinctive artistic style for painting bowls with finely drawn geometric figures and wildlife, especially birds, in black on a white background. Beginning about 600 CE, the Hohokam, living in what is now Arizona, built an extensive irrigation system of canals to irrigate the desert and grow fields of corn, beans, and squash. By 1300, their crop yields were supporting the most highly populated settlements in the southwest. The Hohokam decorated pottery with a red-on-buff design and made jewelry of turquoise. In the high desert of New Mexico, the Anasazi, whose name means “ancient enemy” or “ancient ones,” carved homes from steep cliffs accessed by ladders or ropes that could be pulled in at night or in case of enemy attack.

To access their homes, the cliff-dwelling Anasazi used ropes or ladders that could be pulled in at night for safety. These pueblos may be viewed today at the Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Roads extending some 180 miles connected the Pueblos’ smaller urban centers to each other and to Chaco Canyon, which by 1050 CE had become the administrative, religious, and cultural center of their civilization. A century later, however, probably because of drought, the Pueblo peoples abandoned their cities. Their present-day descendants include the Hopi and Zuni Nations.

INDIANS OF THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER VALLEY

The Indian groups who lived in the present-day Ohio River Valley and achieved their cultural apex from the first century CE to 400 CE are collectively known as the Hopewell culture. Their settlements, unlike those of the southwest, were small hamlets. They lived in wattle-and-daub houses (made from woven lattice branches “daubed” with wet mud, clay, or sand and straw) and practiced agriculture, which they supplemented by hunting and fishing. Utilizing waterways, they developed trade routes stretching from Canada to Louisiana, where they exchanged goods with other peoples and negotiated in many different languages. From the coast they received shells; from Canada, copper; and from the Rocky Mountains, obsidian. With these materials they created necklaces, woven mats, and exquisite carvings.

The largest indigenous cultural and population center in North America was located along the Mississippi River near present-day St. Louis. At its height in about 1100 CE, this five-square-mile city, now called Cahokia, was home to more than ten thousand residents; tens of thousands more lived on farms surrounding the urban center. The city also contained one hundred and twenty earthen mounds or pyramids, each dominating a particular neighborhood and on each of which lived a leader who exercised authority over the surrounding area. The largest mound covered fifteen acres. Cahokia was the hub of political and trading activities along the Mississippi River. After 1300 CE, however, this civilization declined—possibly because the area became unable to support the large population.

INDIANS OF THE EASTERN WOODLAND

The indigenous peoples living east of the Mississippi did not construct the large and complex societies of those to the west. Because they lived in small autonomous clans or social units, each group adapted to the specific environment in which it lived. These groups were by no means unified, and conflicts among them were common as they sought to expand their hunting and fishing areas. Still, these communities shared some common traits. A chief or group of elders made decisions, and although the chief was male, the women usually selected and counseled him. Gender roles were not as fixed as they were in the patriarchal societies of Europe, Mesoamerica, and South America.

Women typically cultivated corn, beans, and squash and harvested nuts and berries, while men hunted, fished, and provided protection. Both men and women took responsibility for raising children, and most major Indigenous societies in the east were matriarchal. In nations such as the Haudenosaunee, Lenape, Muscogee, Cherokee, and Huron-Wendat, women held both power and influence. They counseled the chief and passed on the traditions of the community. In these societies, leadership was often shared, and while the chief was typically a man, women played a vital role in selecting and advising him. The Muscogee, who lived in present-day Georgia, Alabama, and parts of Florida, along with groups such as the Iroquois, Lenape, and Cherokee, upheld the tradition of matriarchy, where women passed on cultural knowledge and ensured the community’s well-being.

The Haudenosaunee, also known as the Iroquois Confederacy, was a powerful and influential alliance of Indigenous nations in present-day New York state. Founded in the 16th century, the Confederacy was a democratic government that brought together the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and later the Tuscarora nations. The Huron-Wendat, located to the north and west of the Haudenosaunee, were another influential group.

Although Indigenous communities often claimed the right to certain hunting grounds—usually identified by some geographical landmark—they did not practice private ownership of land in the European sense. Instead, Native peoples had a communal understanding of land use, where land was viewed as a shared resource to be cared for and passed on to future generations. This perspective emphasized harmony with the land, ensuring that it could continue to provide for the community.

This map indicates the locations of the three Pueblo cultures the major Eastern Woodland Indian Nations, and the Nations of the Southeast, as well as the location of the ancient city of Cahokia. Source: Wikimedia Commons

1.1 Section Summary

Great civilizations had risen and fallen in the Americas before the arrival of the Europeans. In North America, complex societies including the Mogollon, Hohokam, and Anasazi as well as the civilization at Cahokia had peaked and were largely memories. The Eastern Woodland peoples were thriving, but they were soon overwhelmed as the number of English, French, and Dutch settlers increased. Mesoamerica and South America had also witnessed the rise and fall of cultures. The once-mighty Mayan population centers were largely empty. In 1492, however, the Aztecs in Mexico City were at their peak. Subjugating surrounding Nations and requiring tribute of both humans for sacrifice and goods for consumption, the island city of Tenochtitlan was the hub of an ever-widening commercial center and the equal of any large European city until Cortés destroyed it. Further south in Peru, the Inca linked one of the largest empires in history through the use of roads and disciplined armies. Without the use of the wheel, they cut and fashioned stone to build Machu Picchu high in the Andes before abandoning the city for unknown reasons. Thus, depending on what part of the Americas they explored, Europeans encountered peoples that diverged widely in their cultures, traditions, and numbers.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe Portuguese exploration of the Atlantic and Spanish exploration of the Americas, and the importance of these voyages to the developing Atlantic World

- Explain the importance of Spanish exploration of the Americas in the expansion of Spain’s empire and the development of Spanish Renaissance culture

Portuguese colonization of Atlantic islands in the 1400s inaugurated an era of aggressive European expansion across the Atlantic. In the 1500s, Spain surpassed Portugal as the dominant European power. This age of exploration and the subsequent creation of an Atlantic World was a time in which previously isolated groups—Africans, Native Americans, and Europeans—first came into contact with each other, sometimes with disastrous results.

PORTUGUESE EXPLORATION

Portugal’s Prince Henry the Navigator spearheaded his country’s exploration of Africa and the Atlantic in the 1400s. With his support, Portuguese mariners successfully navigated an eastward route to Africa, establishing a foothold there that became a foundation of their nation’s trade empire in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Portuguese mariners built an Atlantic empire by colonizing the Canary, Cape Verde, and Azores Islands, as well as the island of Madeira. Merchants then used these Atlantic outposts as debarkation points for subsequent journeys. From these strategic points, Portugal spread its empire down the western coast of Africa to the Congo, along the western coast of India, and eventually to Brazil on the eastern coast of South America. It also established trading posts in China and Japan.

The travels of Portuguese traders to western Africa introduced them to the African slave trade. Seeing the value of this source of labor in growing the profitable crop of sugar on their Atlantic islands, the Portuguese soon began exporting African enslaved people along with African ivory and gold. Sugar fueled the Atlantic slave trade, and the Portuguese islands quickly became home to sugar plantations. The Portuguese also traded these enslaved people, introducing much-needed human capital to other European nations. In the following years, as European exploration spread, slavery spread as well. In time, much of the Atlantic World would become a gargantuan sugar-plantation complex in which Africans labored to produce the highly profitable commodity for European consumers.

|

|

AMERICANA |

| Elmina Castle

In 1482, Portuguese traders built Elmina Castle (also called São Jorge da Mina, or Saint George’s of the Mine) in present-day Ghana, on the west coast of Africa. A fortified trading post, it had mounted cannons facing out to sea, not inland toward continental Africa; the Portuguese had greater fear of a naval attack from other Europeans than of a land attack from Africans. Portuguese traders soon began to settle around the fort and established the town of Elmina. Although the Portuguese originally used the fort primarily for trading gold, by the sixteenth century they had shifted their focus. The dungeon of the fort now served as a holding pen for African slaves from the interior of the continent, while on the upper floors Portuguese traders ate, slept, and prayed in a chapel. Enslaved people lived in the dungeon for weeks or months until ships arrived to transport them to Europe or the Americas. For them, the dungeon of Elmina was their last sight of their home country. Elmina Castle on the west coast of Ghana was used as a holding pen for enslaved people before they were brought across the Atlantic and sold. Originally built by the Portuguese in the fifteenth century, it appears in the image below as it was in the 1660s, after being seized by Dutch slave traders in 1637.

|

|

SPANISH EXPLORATION AND CONQUEST

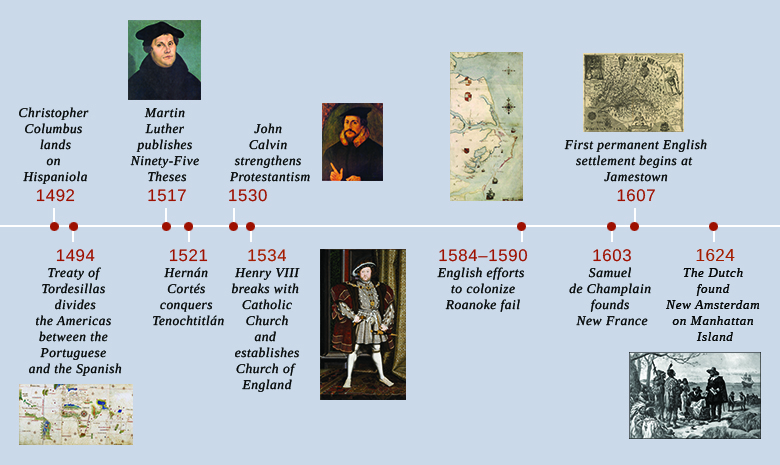

The Spanish established the first European settlements in the Americas, beginning in the Caribbean and, by 1600, extending throughout Central and South America. Thousands of Spaniards flocked to the Americas seeking wealth and status. The most famous of these Spanish adventurers are Christopher Columbus (who, though Italian himself, explored on behalf of the Spanish monarchs), Hernán Cortés, and Francisco Pizarro.

To understand the reasons for Spanish exploration, it is important to know something about the history of Spain. During the fifteenth century, Spain hoped to gain advantage over its rival, Portugal. The marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile in 1469 unified Catholic Spain and began the process of building a nation that could compete for worldwide power. Their goals were to expand Catholicism and to gain a commercial advantage over Portugal. To those ends, Ferdinand and Isabella sponsored extensive Atlantic exploration. Ferdinand and Isabella agreed to finance Columbus’s expedition in 1492, supplying him with three ships: the Nina, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria. The Spanish monarchs knew that Portuguese mariners had reached the southern tip of Africa and sailed the Indian Ocean. They understood that the Portuguese would soon reach Asia and, in this competitive race to reach the Far East, the Spanish rulers decided to act.

Columbus held erroneous views that shaped his thinking about what he would encounter as he sailed west. He believed the earth to be much smaller than its actual size and, since he did not know of the existence of the Americas, he fully expected to land in Asia. On October 12, 1492, however, he made landfall on an island in the Bahamas. He then sailed to an island he named Hispaniola (present-day Dominican Republic and Haiti). Believing he had landed in the East Indies, Columbus called the native Taínos he found there “Indios,” giving rise to the term “Indian” for any native people of the Americas. Upon Columbus’s return to Spain, the Spanish crown bestowed on him the title of Admiral of the Ocean Sea and named him governor and viceroy of the lands he had discovered.

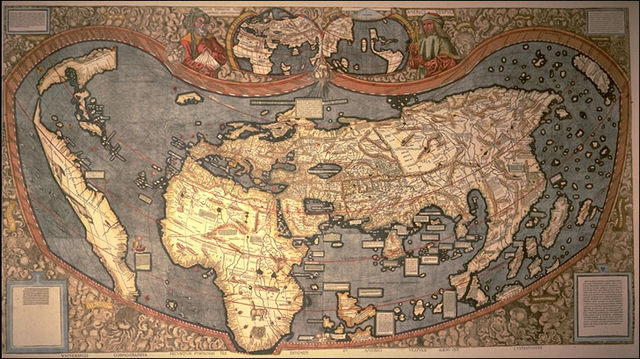

Many other Europeans followed in Columbus’s footsteps, drawn by dreams of winning wealth by sailing west. Another Italian, Amerigo Vespucci, sailing for the Portuguese crown, explored the South American coastline between 1499 and 1502. Unlike Columbus, he realized that the Americas were not part of Asia but lands unknown to Europeans. Vespucci’s widely published accounts of his voyages fueled speculation and intense interest in the Americas among Europeans. Among those who read Vespucci’s reports was the German mapmaker, Martin Waldseemuller. Using the explorer’s first name as a label for the new landmass, Waldseemuller attached “America” to his map of the Americas in 1507, and the name stuck.

A colorized version of the 1507 map drawn by Martin Waldeseemuller. Source: Wikimedia Commons

A colorized version of the 1507 map drawn by Martin Waldeseemuller. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Columbus’s discovery opened a floodgate of Spanish exploration. Inspired by tales of rivers of gold and timid, malleable natives, later Spanish explorers were relentless in their quest for land and gold. Hernán Cortés hoped to gain hereditary privilege for his family, tribute payments and labor from natives, and an annual pension for his service to the crown. Cortés arrived on Hispaniola in 1504 and took part in the conquest of that island. In anticipation of winning his own honor and riches, Cortés explored the Yucatán Peninsula. In 1519, he entered Tenochtitlán, the capital of the Aztec (Mexica) Empire. He and his men were astonished by the incredibly sophisticated causeways, gardens, and temples in the city. Above all else, the Aztec wealth in gold fascinated the Spanish adventurers.

Spain’s acquisitiveness seemingly knew no bounds as groups of its explorers searched for the next trove of instant riches. One such explorer, Francisco Pizarro, made his way to the Spanish Caribbean in 1509, drawn by the promise of wealth and titles. He participated in successful expeditions in Panama before following rumors of Inca wealth to the south. Although his first efforts against the Inca Empire in the 1520s failed, Pizarro captured the Inca emperor Atahualpa in 1532 and executed him one year later. In 1533, Pizarro founded Lima, Peru. Like Cortés, Pizarro had to combat not only the natives of the Americas he was conquering, but also competitors from his own country; a Spanish rival assassinated him in 1541.

Spain’s drive to enlarge its empire led other hopeful conquistadors to push further into the Americas, hoping to replicate the success of Cortés and Pizarro. Hernando de Soto had participated in Pizarro’s conquest of the Inca, and from 1539 to 1542 he led expeditions to what is today the southeastern United States, looking for gold. He and his followers explored what is now Florida, Georgia, the Carolinas, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Texas. Everywhere they traveled, they brought European diseases, which claimed thousands of native lives as well as the lives of the explorers. In 1542, de Soto himself died during the expedition. The surviving Spaniards, numbering a little over three hundred, returned to Mexico City without finding the much-anticipated mountains of gold and silver.

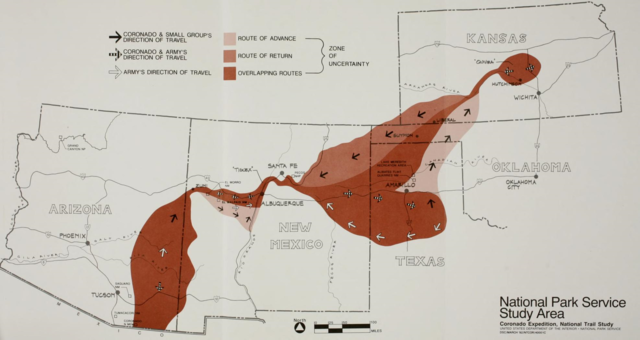

Francisco Vásquez de Coronado was born into a noble family and went to Mexico, then called New Spain, in 1535. He presided as governor over the province of Nueva Galicia, where he heard rumors of wealth to the north: a golden city called Quivira. Between 1540 and 1542, Coronado led a large expedition of Spaniards and native allies to the lands north of Mexico City, and for the next several years, they explored the area that is now the southwestern United States. During the winter of 1540–41, the explorers waged war against the Tiwa in present-day New Mexico. Rather than leading to the discovery of gold and silver, however, the expedition simply left Coronado bankrupt.

This map traces Coronado’s path through the American Southwest and the Great Plains. The regions through which he traveled were not empty areas waiting to be “discovered”: rather, they were populated and controlled by the groups of native peoples indicated. Source: Wikimedia Commons

1.2 Section Summary

Although Portugal opened the door to exploration of the Atlantic World, Spanish explorers quickly made inroads into the Americas. Spurred by Christopher Columbus’s glowing reports of the riches to be found in the Americas, throngs of Spanish conquistadors set off to find and conquer new lands. They accomplished this through a combination of military strength and strategic alliances with native peoples. Spanish rulers Ferdinand and Isabella promoted the acquisition of these new lands in order to strengthen and glorify their own empire.

1.3 Challenges to Spain’s Supremacy

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify regions where the English, French, and Dutch explored and established settlements

- Describe the differences among the early colonies

- Explain the role of the American colonies in European nations’ struggles for domination

For Europeans, the discovery of an Atlantic World meant newfound wealth in the form of gold and silver as well as valuable furs. The Americas also provided a new arena for intense imperial rivalry as different European nations jockeyed for preeminence in the Americas.

ENGLISH EXPLORATION

English monarchs carefully monitored developments in the new Atlantic World and took steps to assert England’s claim to the Americas. As early as 1497, Henry VII of England had commissioned John Cabot, an Italian mariner, to explore new lands. Cabot sailed from England that year and made landfall somewhere along the North American coastline. For the next century, English fishermen routinely crossed the Atlantic to fish the rich waters off the North American coast. Queen Elizabeth approved of English privateers, sea captains to whom the home government had given permission to raid the enemy at will. These skilled mariners cruised the Caribbean, plundering Spanish ships whenever they could. Each year the English took more than £100,000 from Spain in this way.

Elizabeth sanctioned the first English attempt at colonization in 1584, when Sir Walter Raleigh attempted to establish a colony at Roanoke, an island off the coast of present-day North Carolina. The colony was small, consisting of only 117 people, who suffered a poor relationship with the local Indians, the Croatans, and struggled to survive in their new land. Their governor, John White, returned to England in late 1587 to secure more people and supplies, but events conspired to keep him away from Roanoke for three years. By the time he returned in 1590, the entire colony had vanished. The only trace the colonists left behind was the word Croatoan carved into a fence surrounding the village. Governor White never knew whether the colonists had decamped for nearby Croatoan Island (now Hatteras) or whether some disaster had befallen them all. Roanoke is still called “the lost colony.”

An unknown pencil drawing depicts English settlers discovering the word “Croatoan.” Source: Wikimedia Commons

English promoters of colonization pushed its commercial advantages and the religious justification that English colonies would allow the establishment of Protestant Christianity in the Americas. Both arguments struck a chord. In the early 1600s, wealthy English merchants and the landed elite began to pool their resources to form joint stock companies. In this novel business arrangement, which was in many ways the precursor to the modern corporation, investors provided the capital for and assumed the risk of a venture in order to reap significant returns. The companies gained the approval of the English crown to establish colonies, and their investors dreamed of reaping great profits from the money they put into overseas colonization.

The first permanent English settlement was established by a joint stock company, the Virginia Company. Named for Elizabeth, the “virgin queen,” the company gained royal approval to establish a colony on the east coast of North America, and in 1606, it sent 144 men and boys to the Americas. In early 1607, this group sailed up Chesapeake Bay. Finding a river they called the James in honor of their new king, James I, they established a ramshackle settlement and named it Jamestown. Despite serious struggles, the colony survived.

By any measure, England came late to the race to colonize. As Jamestown limped along in the 1610s, the Spanish Empire extended around the globe and grew rich from its global colonial project. Yet the English persisted, and for this reason the Jamestown settlement has a special place in history as the first permanent colony in what later became the United States.

After Jamestown’s founding, English colonization of the Americas accelerated. In 1609, a ship bound for Jamestown foundered in a storm and landed on Bermuda. The admiral of the ship, George Somers, claimed the island for the English crown. The English also began to colonize small islands in the Caribbean, an incursion into the Spanish American empire. They established themselves on small islands such as St. Christopher (1624), Barbados (1627), Nevis (1628), Montserrat (1632), and Antigua (1632).

|

|

MY STORY |

| George Percy and the First Months at Jamestown

The 144 men and boys who started the Jamestown colony faced many hardships; by the end of the first winter, only 38 had survived. Disease, hunger, and poor relationships with local natives all contributed to the colony’s high death toll. George Percy, who served twice as governor of Jamestown, kept records of the colonists’ first months in the colony. These records were later published in London in 1608. This excerpt is from his account of August and September of 1607. “The fourth day of September died Thomas Jacob Sergeant. The fifth day, there died Benjamin Beast. Our men were destroyed with cruel diseases, as Swellings, Fluxes, Burning Fevers, and by wars, and some departed suddenly, but for the most part they died of mere famine. There were never Englishmen left in a foreign Country in such misery as we were in this new discovered Virginia… . Our food was but a small Can of Barley sod (soaked) in water, to five men a day, our drink cold water taken out of the River, which was at a flood very salty, at a low tide full of slime and filth, which was the destruction of many of our men. Thus we lived for the space of five months in this miserable distress, not having five able men to man our Bulwarks upon any occasion. If it had not pleased God to have put a terror in the Savages’ hearts, we had all perished by those wild and cruel Pagans, being in that weak estate as we were; our men night and day groaning in every corner of the Fort most pitiful to hear. If there were any conscience in men, it would make their hearts to bleed to hear the pitiful murmurings and outcries of our sick men without relief, every night and day, for the space of six weeks, some departing out of the World, many times three or four in a night; in the morning, their bodies trailed out of their Cabins like Dogs to be buried. In this sort did I see the mortality of diverse of our people.” |

|

In comparison to Spain, however, England remained a very weak imperial player in the early seventeenth century, with only a few infant colonies in the Americas in the early 1600s. The English never found treasure equal to that of the Aztec city of Tenochtitlán, and England did not quickly grow rich from its small American outposts. The English colonies also differed from each other; Barbados and Virginia had a decidedly commercial orientation from the start, while the Puritan colonies of New England were intensely religious at their inception. All English settlements in America, however, marked the increasingly important role of England in the Atlantic World.

From the start, the English West Indies had a commercial orientation, for these islands produced cash crops: first tobacco and then sugar. Very quickly, by the mid-1600s, Barbados had become one of the most important English colonies because of the sugar produced there. Barbados was the first English colony dependent on enslaved people, and it became a model for other English slave societies on the American mainland. These differed radically from England itself, where slavery was not practiced.

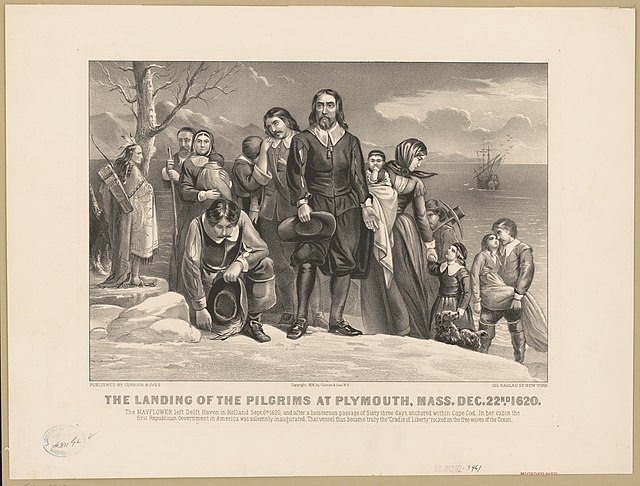

English Puritans also began to colonize the Americas in the 1620s and 1630s. These intensely religious migrants dreamed of creating communities of reformed Protestantism where the corruption of England would be eliminated. One of the first groups of Puritans to move to North America, known as Pilgrims and led by William Bradford, had originally left England to live in the Netherlands. Fearing their children were losing their English identity among the Dutch, however, they sailed for North America in 1620 to settle at Plymouth, the first English settlement in New England. The Pilgrims differed from other Puritans in their insistence on separating from what they saw as the corrupt Church of England. For this reason, Pilgrims are known as Separatists. In 1630, a much larger contingent of Puritans left England to escape conformity to the Church of England and founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony. In the following years, thousands more arrived to create a new life in the rocky soils and cold climates of New England.

This is a 19th century Currier and Ives lithograph depicting the Pilgrims landing at Plymouth Rock. The Mayflower is anchored offshore to the right. Source: Wikimedia Commons

FRENCH EXPLORATION

Spanish exploits in the Americas whetted the appetite of other would-be imperial powers, including France. Like Spain, France was a Catholic nation and committed to expanding Catholicism around the globe. In the early sixteenth century, it joined the race to explore the Americas and exploit the resources of the Western Hemisphere. Navigator Jacques Cartier claimed northern North America for France, naming the area New France. From 1534 to 1541, he made three voyages of discovery on the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the St. Lawrence River. Like other explorers, Cartier made exaggerated claims of mineral wealth in America, but he was unable to send great riches back to France. Due to resistance from the native peoples as well as his own lack of planning, he could not establish a permanent settlement in North America.

Explorer Samuel de Champlain occupies a special place in the history of the Atlantic World for his role in establishing the French presence in the Americas. Champlain explored the Caribbean in 1601 and then the coast of New England in 1603 before traveling farther north. In 1608 he founded Quebec, and he made numerous Atlantic crossings as he worked tirelessly to promote New France. Unlike other imperial powers, France—through Champlain’s efforts—fostered especially good relationships with native peoples, paving the way for French exploration further into the continent: around the Great Lakes, around Hudson Bay, and eventually to the Mississippi. Champlain made an alliance with the Huron confederacy and the Algonquins and agreed to fight with them against their enemy, the Iroquois.

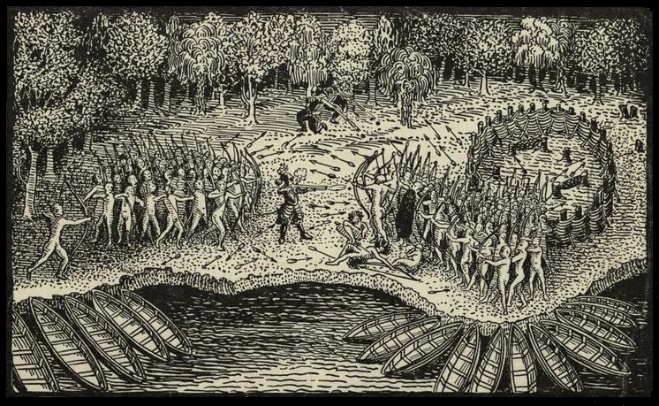

This engraving, titled “Defeat of the Iroquois,” was based on a drawing by explorer Samuel de Champlain, Champlain is shown fighting on the side of the Huron and Algonquins against the Iroquois. He portrays himself in the middle of the battle, firing a gun, while the native people around him shoot arrows at each other. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The French were primarily interested in establishing commercially viable colonial outposts, and to that end, they created extensive trading networks in New France. These networks relied on native hunters to harvest furs, especially beaver pelts, and to exchange these items for French glass beads and other trade goods. (French fashion at the time favored broad-brimmed hats trimmed in beaver fur, so French traders had a ready market for their North American goods.) The French also dreamed of replicating the wealth of Spain by colonizing the tropical zones. After Spanish control of the Caribbean began to weaken, the French turned their attention to small islands in the West Indies, and by 1635 they had colonized two, Guadeloupe and Martinique. Though it lagged far behind Spain, France now boasted its own West Indian colonies. Both islands became lucrative sugar plantation sites that turned a profit for French planters by relying on the labor of enslaved people from Africa.

DUTCH COLONIZATION

Dutch entrance into the Atlantic World is part of the larger story of religious and imperial conflict in the early modern era. In the 1500s, Calvinism, one of the major Protestant reform movements, had found adherents in the northern provinces of the Spanish Netherlands. During the sixteenth century, these provinces began a long struggle to achieve independence from Catholic Spain. Established in 1581 but not recognized as independent by Spain until 1648, the Dutch Republic, or Holland, quickly made itself a powerful force in the race for Atlantic colonies and wealth. The Dutch distinguished themselves as commercial leaders in the seventeenth century, and their mode of colonization relied on powerful corporations: the Dutch East India Company, chartered in 1602 to trade in Asia, and the Dutch West India Company, established in 1621 to colonize and trade in the Americas.

While employed by the Dutch East India Company in 1609, the English sea captain Henry Hudson explored New York Harbor and the river that now bears his name. Like many explorers of the time, Hudson was actually seeking a northwest passage to Asia and its wealth, but the ample furs harvested from the region he explored, especially the coveted beaver pelts, provided a reason to claim it for the Netherlands. The Dutch named their colony New Netherlands, and it served as a fur-trading outpost for the expanding and powerful Dutch West India Company. With headquarters in New Amsterdam on the island of Manhattan, the Dutch set up several regional trading posts, including one at Fort Orange—named for the royal Dutch House of Orange-Nassau—in present-day Albany. A brisk trade in furs with local Algonquian and Iroquois peoples brought the Dutch and native peoples together in a commercial network that extended throughout the Hudson River Valley and beyond. The Dutch West India Company in turn established colonies on the islands of Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao, St. Martin, St. Eustatius, and Saba. With their outposts in New Netherlands and the Caribbean, the Dutch established themselves in the seventeenth century as a commercially powerful rival to Spain. Amsterdam became a trade hub for all the Atlantic World.

By the beginning of the seventeenth century, Spain’s rivals—England, France, and the Dutch Republic—had each established an Atlantic presence, with greater or lesser success, in the race for imperial power. None of the new colonies, all in the eastern part of North America, could match the Spanish possessions for gold and silver resources. Nonetheless, their presence in the Americas helped these nations establish claims that they hoped could halt the runaway growth of Spain’s Catholic empire. English colonists in Virginia suffered greatly, expecting riches to fall into their hands and finding reality a harsh blow. However, the colony at Jamestown survived, and the output of England’s islands in the West Indies soon grew to be an important source of income for the country. New France and New Netherlands were modest colonial holdings in the northeast of the continent, but these colonies’ thriving fur trade with native peoples, and their alliances with those peoples, helped to create the foundation for later shifts in the global balance of power.

1.3 Section Summary

By the beginning of the seventeenth century, Spain’s rivals—England, France, and the Dutch Republic—had each established an Atlantic presence, with greater or lesser success, in the race for imperial power. None of the new colonies, all in the eastern part of North America, could match the Spanish possessions for gold and silver resources. Nonetheless, their presence in the Americas helped these nations establish claims that they hoped could halt the runaway growth of Spain’s Catholic empire. English colonists in Virginia suffered greatly, expecting riches to fall into their hands and finding reality a harsh blow. However, the colony at Jamestown survived, and the output of England’s islands in the West Indies soon grew to be an important source of income for the country. New France and New Netherlands were modest colonial holdings in the northeast of the continent, but these colonies’ thriving fur trade with native peoples, and their alliances with those peoples, helped to create the foundation for later shifts in the global balance of power.

1.4 Enforced Labor, Commerce, and the Columbian Exchange in the Americas

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe how Europeans solved their labor problems

- Describe the theory of mercantilism and the process of commodification

- Analyze the effects of the Columbian Exchange

European promoters of colonization claimed the Americas overflowed with a wealth of treasures. Burnishing national glory and honor became entwined with carving out colonies, and no nation wanted to be left behind. However, the realities of life in the Americas—violence, exploitation, and particularly the need for workers—were soon driving the practice of slavery and forced labor. Everywhere in America a stark contrast existed between freedom and slavery. The Columbian Exchange, in which Europeans transported plants, animals, and diseases across the Atlantic in both directions, also left a lasting impression on the Americas.

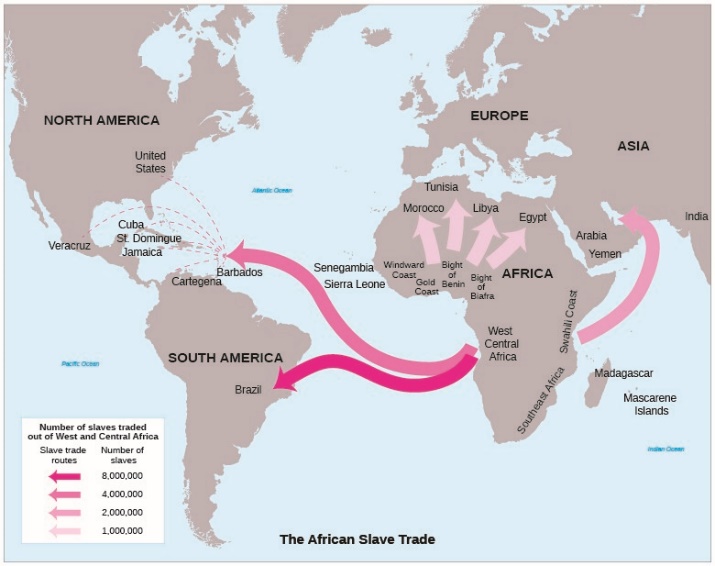

This map shows the routes that were used in the course of the slave trade and the number of enslaved people who traveled each route. As the figures indicate, most African slaves were bound for Brazil and the Caribbean. While West Africans made up the vast majority of the enslaved, the east coast of Africa, too, supplied enslaved people for the trade. Source: Wikimedia Commons

LABOR SYSTEMS

Physical power—to work the fields, build villages, process raw materials—is a necessity for maintaining a society. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, humans could derive power only from the wind, water, animals, or other humans. Everywhere in the Americas, a crushing demand for labor bedeviled Europeans because there were not enough colonists to perform the work necessary to keep the colonies going. Spain granted encomiendas—legal rights to native labor—to conquistadors who could prove their service to the crown.

In this startling image from the Kingsborough Codex (a book written and drawn by native Mesoamericans), a well-dressed Spaniard is shown pulling the hair of a bleeding, severely injured native. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The system of encomiendas was accompanied by a great deal of violence. One Spaniard, Bartolomé de Las Casas, denounced the brutality of Spanish rule. A Dominican friar, Las Casas had been one of the earliest Spanish settlers in the Spanish West Indies. In his early life in the Americas, he owned Indian slaves and was the recipient of an encomienda. However, after witnessing the savagery with which encomenderos (recipients of encomiendas) treated the native people, he reversed his views. In 1515, Las Casas released his native slaves, gave up his encomienda, and began to advocate for humane treatment of native peoples. He lobbied for new legislation, eventually known as the New Laws, which would eliminate slavery and the encomienda system.

Las Casas’ writing about the Spaniards’ horrific treatment of Indians helped inspire the so-called Black Legend, the idea that the Spanish were bloodthirsty conquerors with no regard for human life. Perhaps not surprisingly, those who held this view of the Spanish were Spain’s imperial rivals. English writers and others seized on the idea of Spain’s ruthlessness to support their own colonization projects. By demonizing the Spanish, they justified their own efforts as more humane. All European colonizers, however, shared a disregard for Indians.

|

|

MY STORY |

| Bartolomé de Las Casas on the Mistreatment of Indians

Bartolomé de Las Casas’s A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, written in 1542 and published ten years later, detailed for Prince Philip II of Spain how Spanish colonists had been mistreating natives. “Into and among these gentle sheep, endowed by their Maker and Creator with all the qualities aforesaid, did creep the Spaniards, who no sooner had knowledge of these people than they became like fierce wolves and tigers and lions who have gone many days without food or nourishment. And no other thing have they done for forty years until this day, and still today see fit to do, but dismember, slay, perturb, afflict, torment, and destroy the Indians by all manner of cruelty—new and divers and most singular manners such as never before seen or read or heard of—some few of which shall be recounted below, and they do this to such a degree that on the Island of Hispaniola, of the above three millions souls that we once saw, today there be no more than two hundred of those native people remaining. . . . “Two principal and general customs have been employed by those, calling themselves Christians, who have passed this way, in extirpating and striking from the face of the earth those suffering nations. The first being unjust, cruel, bloody, and tyrannical warfare. The other—after having slain all those who might yearn toward or suspire after or think of freedom, or consider escaping from the torments that they are made to suffer, by which I mean all the native-born lords and adult males, for it is the Spaniards’ custom in their wars to allow only young boys and females to live—being to oppress them with the hardest, harshest, and most heinous bondage to which men or beasts might ever be bound into.” |

|

Indians were not the only source of cheap labor in the Americas; by the middle of the sixteenth century, enslaved people imported from African formed an important element of the labor landscape, producing the cash crops of sugar and tobacco for European markets. The major European slave trade began with Portugal’s exploration of the west coast of Africa in search of a trade route to the East. By 1444, enslaved people were being brought from Africa to work on the sugar plantations of the Madeira Islands, off the coast of modern Morocco. The slave trade then expanded greatly as European colonies in the Americas demanded an ever-increasing number of workers for the extensive plantations growing tobacco, sugar, and eventually rice and cotton.

Europeans viewed Africans as non-Christians, which they used as a justification for enslavement. Denied control over their lives, enslaved people endured horrendous conditions. At every opportunity, they resisted enslavement, and their resistance was met with violence. Indeed, physical, mental, and sexual violence formed a key strategy among European slaveholders in their effort to assert mastery and impose their will. The Portuguese led the way in the evolving transport of slaves across the Atlantic; slave “factories” on the west coast of Africa, like Elmina Castle in Ghana, served as holding pens for slaves brought from Africa’s interior. In time, other European imperial powers would follow in the footsteps of the Portuguese by constructing similar outposts on the coast of West Africa.

The European slave trade began with Portugal’s exploration of the west coast of Africa in search of a trade route to the East. The Portuguese traded or sold enslaved people to Spanish, Dutch, and English colonists in the Americas, particularly in South America and the Caribbean, where sugar was a primary export. Thousands of African slaves found themselves growing, harvesting, and processing sugarcane in an arduous routine of physical labor. Enslaved people had to cut the long cane stalks by hand and then bring them to a mill, where the cane juice was extracted. They boiled the extracted cane juice down to a brown, crystalline sugar, which then had to be cured in special curing houses to have the molasses drained from it. The result was refined sugar, while the leftover molasses could be distilled into rum. Every step was labor-intensive and often dangerous. The slave trade expanded greatly as European colonies in the Americas demanded an ever-increasing number of workers for the extensive plantations growing tobacco, sugar, and eventually rice and cotton.

In the Americas, the institution of slavery assumed a new aspect because of the need for a permanent, identifiable, and plentiful labor supply. Enslaved people from Africa were both easily identified (by their skin color) and plentiful, because of the thriving slave trade. This led to a race-based slavery system in the Americas unlike any bondage system that had come before. Initially, the Spanish tried to force Indians to farm their crops. Most Spanish and Portuguese settlers coming to the Americas were gentlemen and did not perform physical labor. However, enslaved natives tended to sicken or die from disease or from the overwork and cruel treatment they were subjected to, and so the indigenous peoples proved not to be a dependable source of labor. These workers proved hardier, and within fifty years, a change took place: The profitability of the African slave trade, coupled with the seemingly limitless number of potential slaves and the Catholic Church’s denunciation of the enslavement of Christians, led race to become a dominant factor in the institution of slavery.

In the English colonies along the Atlantic coast, indentured servants initially filled the need for labor in the North, where family farms were the norm. In the South, labor-intensive crops such as tobacco, rice, and indigo prevailed, and eventually the supply of indentured servants was insufficient to meet the demand. These workers served only for periods of three to seven years before being freed; a more permanent labor supply was needed. Slavery became permanent, and children born to enslaved people were themselves enslaved. This development, along with slavery’s identification with race, forever changed the institution and shaped its unique character in the Americas.

COMMERCE IN THE AMERICAS

The economic philosophy of mercantilism shaped European perceptions of wealth from the 1500s to the late 1700s. Mercantilism held that only a limited amount of wealth, as measured in gold and silver bullion, existed in the world. In order to gain power, nations had to amass wealth by mining these precious raw materials from their colonial possessions. During the age of European exploration, nations employed conquest, colonization, and trade as ways to increase their share of the bounty of the Americas. Mercantilists did not believe in free trade, arguing instead that the nation should control trade to create wealth. In this view, colonies existed to strengthen the colonizing nation. Mercantilists argued against allowing their nations to trade freely with other nations.

Spain’s mercantilist ideas guided its economic policy. Every year, slaves or native workers loaded shipments of gold and silver aboard Spanish treasure fleets that sailed from Cuba for Spain. These ships groaned under the sheer weight of bullion, for the Spanish had found huge caches of silver and gold in the Americas. In South America, for example, Spaniards discovered rich veins of silver ore in the mountain called Potosí and founded a settlement of the same name there. Throughout the sixteenth century, Potosí was a boom town, attracting settlers from many nations as well as native people from many different cultures.

Colonial mercantilism, which was basically a set of protectionist policies designed to benefit the nation, relied on several factors: colonies rich in raw materials, cheap labor, colonial loyalty to the home government, and control of the shipping trade. Under this system, the colonies sent their raw materials, harvested by slaves or native workers, back to their mother country. The mother country sent back finished materials of all sorts: textiles, tools, clothing. The colonists could purchase these goods only from their mother country; trade with other countries was forbidden.

The 1500s and early 1600s also introduced the process of commodification to the Americas. American silver, tobacco, and other items, which were used by native peoples for ritual purposes, became European commodities with a monetary value that could be bought and sold. Before the arrival of the Spanish, for example, the Inca people of the Andes consumed chicha, a corn beer, for ritual purposes only. When the Spanish discovered chicha, they bought and traded for it, turning it into a commodity instead of a ritual substance. Commodification thus recast native economies and spurred the process of early commercial capitalism. Americas resources, from plants to animal pelts, held the promise of wealth for European imperial powers.

THE COLUMBIAN EXCHANGE

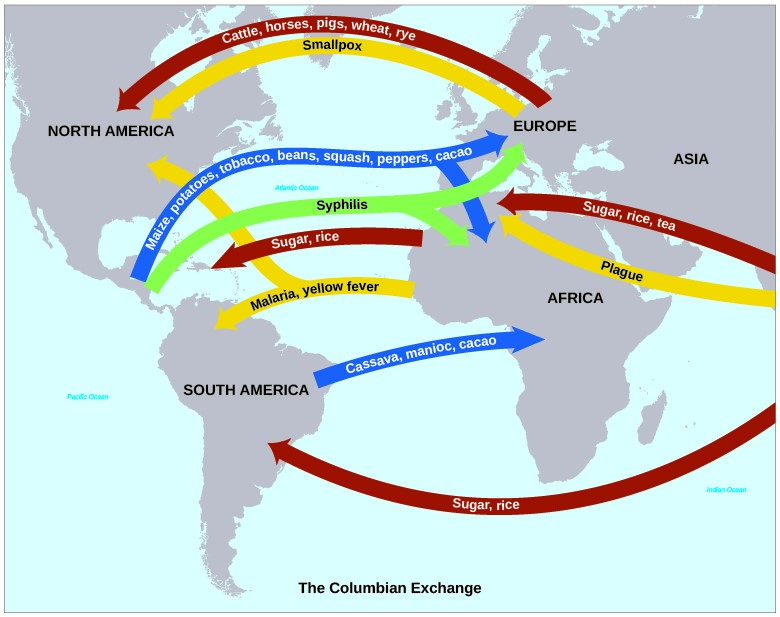

As Europeans traversed the Atlantic, they brought with them plants, animals, and diseases that changed lives and landscapes on both sides of the ocean. These two-way exchanges between the Americas and Europe/Africa are known collectively as the Columbian Exchange.

Of all the commodities in the Atlantic World, sugar proved to be the most important. Indeed, sugar carried the same economic importance as oil does today. European rivals raced to create sugar plantations in the Americas and fought wars for control of some of the best sugar production areas. Although refined sugar was available in the Old World, Europe’s harsher climate made sugarcane difficult to grow, and it was not plentiful. Columbus brought sugar to Hispaniola in 1493, and the new crop was growing there by the end of the 1490s. By the first decades of the 1500s, the Spanish were building sugar mills on the island. Over the next century of colonization, Caribbean islands and most other tropical areas became centers of sugar production.

Though of secondary importance to sugar, tobacco achieved great value for Europeans as a cash crop as well. Native peoples had been growing it for medicinal and ritual purposes for centuries before European contact, smoking it in pipes or powdering it to use as snuff. They believed tobacco could improve concentration and enhance wisdom. To some, its use meant achieving an entranced, altered, or divine state.

Tobacco was unknown in Europe before 1492, and it carried a negative stigma at first. The early Spanish explorers considered natives’ use of tobacco to be proof of their savagery and, because of the fire and smoke produced in the consumption of tobacco, evidence of the Devil’s sway in the Americas. Gradually, however, European colonists became accustomed to and even took up the habit of smoking, and they brought it across the Atlantic. As did the Indians, Europeans ascribed medicinal properties to tobacco, claiming that it could cure headaches and skin irritations. Even so, Europeans did not import tobacco in great quantities until the 1590s. At that time, it became the first truly global commodity; English, French, Dutch, Spanish, and Portuguese colonists all grew it for the world market.

Native peoples also introduced Europeans to chocolate, made from cacao seeds and used by the Aztec in Mesoamerica as currency. Mesoamerican Indians consumed unsweetened chocolate in a drink with chili peppers, vanilla, and a spice called achiote. This chocolate drink—xocolatl—was part of ritual ceremonies like marriage and an everyday item for those who could afford it. Chocolate contains theobromine, a stimulant, which may be why native people believed it brought them closer to the sacred world.

Spaniards in the Americas considered drinking chocolate a vile practice; one called chocolate “the Devil’s vomit.” In time, however, they introduced the beverage to Spain. At first, chocolate was available only in the Spanish court, where the elite mixed it with sugar and other spices. Later, as its availability spread, chocolate gained a reputation as a love potion.

The crossing of the Atlantic by plants like cacao and tobacco illustrates the ways in which the discovery of the Americas changed the habits and behaviors of Europeans. Europeans changed the Americas in turn, not least by bringing Old World animals to the Americas. On his second voyage, Christopher Columbus brought pigs, horses, cows, and chickens to the islands of the Caribbean. Later explorers followed suit, introducing new animals or reintroducing ones that had died out (like horses). With less vulnerability to disease, these animals often fared better than humans in their new home, thriving both in the wild and in domestication.

Europeans encountered Americas animals as well. Because European Christians understood the world as a place of warfare between God and Satan, many believed the Americas, which lacked Christianity, were home to the Devil and his minions. The exotic, sometimes bizarre, appearances and habits of animals in the Americas that were previously unknown to Europeans, such as manatees, sloths, and poisonous snakes, confirmed this association. Over time, however, they began to rely more on observation of the natural world than solely on scripture. This shift—from seeing the Bible as the source of all received wisdom to trusting observation or empiricism—is one of the major outcomes of the era of early globalization.

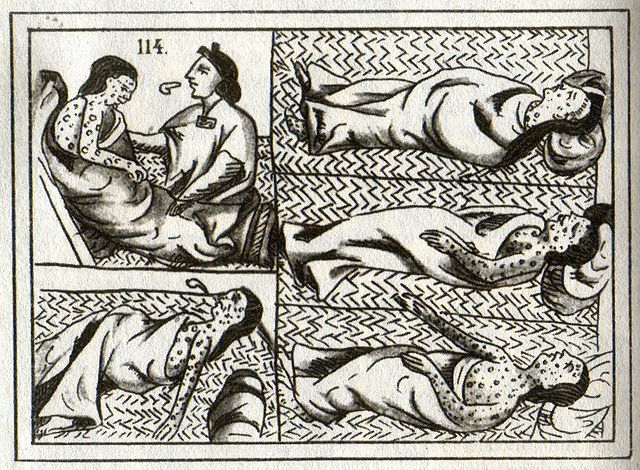

Travelers between the Americas, Africa, and Europe also included microbes: silent, invisible life forms that had profound and devastating consequences. Native peoples had no immunity to diseases from across the Atlantic, to which they had never been exposed. European explorers unwittingly brought with them chickenpox, measles, mumps, and smallpox, which ravaged native peoples despite their attempts to treat the diseases, decimating some populations and wholly destroying others.

This sixteenth-century Aztec drawing shows the suffering of a typical victim of smallpox. Smallpox and other contagious diseases brought by European explorers decimated Indian populations in the Americas. Source: Wikimedia Commons

1.4 Section Summary

In the minds of European rulers, colonies existed to create wealth for imperial powers. Guided by mercantilist ideas, European rulers and investors hoped to enrich their own nations and themselves, in order to gain the greatest share of what was believed to be a limited amount of wealth. In their own individual quest for riches and preeminence, European colonizers who traveled to the Americas blazed new and disturbing paths, such as the encomienda system of forced labor and the use of tens of thousands of Africans as slaves. All native inhabitants of the Americas who came into contact with Europeans found their worlds turned upside down as the new arrivals introduced their religions and ideas about property and goods. Europeans gained new foods, plants, and animals in the Columbian Exchange, turning them into commodities to be bought and sold, and Indians were introduced to diseases that nearly destroyed them. At every turn, however, Indians placed limits on European colonization and resisted the newcomers’ ways.

Summary Timelines

Chapter 1 Self-Test

Chapter 1 Key Term Crossword Puzzle

Citations: This edited book is derivative of US History by P. Scott Corbett, et. al. CC BY 4.0. The original textbook is available at https://openstax.org/details/books/us-history

an ancient land bridge linking Asia and North America

floating Aztec gardens consisting of a large barge woven from reeds, filled with dirt and floating on the water, allowing for irrigation

Incan relay runners used to send messages over great distances

an ancient Incan device for recording information, consisting of variously colored threads knotted in different ways

the Incan labor tax, with each family donating time and work to communal projects

an island in the Caribbean, present-day Haiti and Dominican Republic, where Columbus first landed and established a Spanish colony

sea captains to whom the British government had given permission to raid Spanish ships at will

the first English colony in Virginia, which mysteriously disappeared sometime between 1587 and 1590

a business entity in which investors provide the capital and assume the risk in order to reap significant returns

a group of religious reformers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries who wanted to “purify” the Church of England by ridding it of practices associated with the Catholic Church and advocating greater purity of doctrine and worship

Puritan Separatists, led by William Bradford, who established the first English settlement in New England

a faction of Puritans who advocated complete separation from the Church of England

Spain’s reputation as bloodthirsty conquistadors

one of the primary crops of the Americas, which required a tremendous amount of labor to cultivate

the protectionist economic principle that nations should control trade with their colonies to ensure a favorable balance of trade

the transformation of something—for example, an item of ritual significance—into a commodity with monetary value

the movement of plants, animals, and diseases across the Atlantic due to European exploration of the Americas

a disease that Europeans accidentally brought to the Americas, killing millions of Indians, who had no immunity to the disease