4 Chapter 4: Creating the Nation, 1783–1820

Creating the Nation, 1783–1820

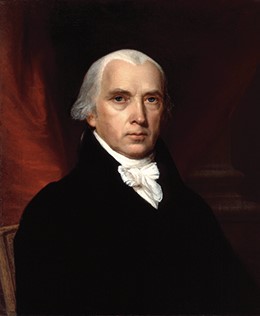

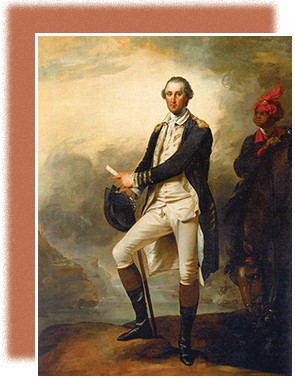

John Trumbull, Washington’s aide-de-camp, painted this wartime image of Washington on a promontory above the Hudson River. Just behind Washington, his enslaved person, William“Billy” Lee, has his eyes firmly fixed on his enslaver. In the far background, British warships fire on an American fort. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Chapter Outline

Introduction, Watch and Learn, Questions to Guide Your Reading

4.1 Common Sense: From Monarchy to an American Republic

4.2 How Much Revolutionary Change?

4.4 The Constitutional Convention and Federal Constitution

4.5 Competing Visions: Federalists and Democratic-Republicans

4.8 The United States Goes Back to War

Summary Timelines, Chapter 4 Self-Test, Chapter 4 Key Terms Crossword Puzzle

Introduction

After the Revolutionary War, the ideology that “all men are created equal” failed to match up with reality, as the revolutionary generation could not solve the contradictions of freedom and slavery in the new United States. Trumbull’s 1780 painting of George Washington hints at some of these contradictions. What attitude do you think Trumbull was trying to convey? Why did Trumbull include Washington’s enslaved person Billy Lee, and what does Lee represent in this painting?

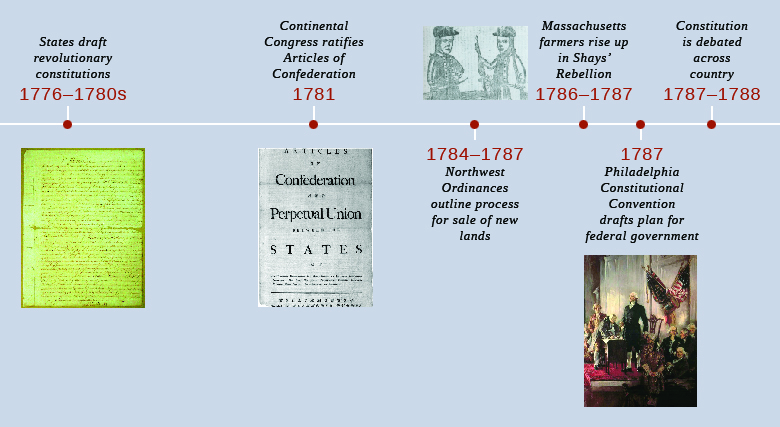

During the 1770s and 1780s, Americans took bold steps to define American equality. Each state held constitutional conventions and crafted state constitutions that defined how government would operate and who could participate in political life. Many elite revolutionaries recoiled in horror from the idea of majority rule—the basic principle of democracy—fearing that it would effectively create a “mob rule” that would bring about the ruin of the hard-fought struggle for independence. Statesmen everywhere believed that a republic should replace the British monarchy: a government where the important affairs would be entrusted only to representative men of learning and refinement.

In the nation’s first few years, no organized political parties existed. This began to change as U.S. citizens argued bitterly about the proper size and scope of the new national government. As a result, the 1790s witnessed the rise of opposing political parties: the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. Federalists saw unchecked democracy as a dire threat to the republic, and they pointed to the excesses of the French Revolution as proof of what awaited. Democratic-Republicans opposed the Federalists’ notion that only the wellborn and well educated were able to oversee the republic; they saw it as a pathway to oppression by an aristocracy.

Watch and Learn (Crash Course in History Videos for chapter 4)

- Phyliss Wheatley

- The Constitution, the Articles, and Federalism

- The US Constitution, 3/5, and the Slave Trade Clause

- Where US Politics Came From

- The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793

- Thomas Jefferson & His Democracy

- The War of 1812

Questions to Guide Your Reading

- In what ways does the United States Constitution manifest the principles of both republican and democratic forms of government? In what ways does it deviate from those principles? Describe popular attitudes toward African Americans, women, and Indians in the wake of the Revolution. In what ways did the established social and political order depend upon keeping members of these groups in their circumscribed roles? If those roles were to change, how would American society and politics have had to adjust?

- How did the process of creating and ratifying the Constitution, and the language of the Constitution itself, confirm the positions of African Americans, women, and Indians in the new republic? How did these roles compare to the stated goals of the republic?

- What were the circumstances that led to Shays’ Rebellion? What was the government’s response? Would this response have confirmed or negated the grievances of the participants in the uprising? Why?

- Describe Alexander Hamilton’s plans to address the nation’s financial woes. Why was it controversial? What elements of the foundation Hamilton laid can still be found in the system today?

- Describe the growth of the first party system in the United States. How did these parties come to develop? How did they define themselves, both independently and in opposition to one another? Where did they find themselves in agreement?

- What led to the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts? What made them so controversial?

- What was the most significant impact of the War of 1812?

4.1 Common Sense: From Monarchy to an American Republic

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Compare and contrast monarchy and republican government

- Describe the tenets of republicanism

While monarchies dominated eighteenth-century Europe, American revolutionaries were determined to find an alternative to this method of government. The Declaration of Independence affirmed the break with England but did not suggest what form of government should replace monarchy, the only system most English colonists had ever known. In the late eighteenth century, republics were few and far between. Genoa, Venice, and the Dutch Republic provided examples of states without monarchs, but many European Enlightenment thinkers questioned the stability of a republic. Nonetheless, after their break from Great Britain, Americans turned to republicanism for their new government.

REPUBLICANISM AS A POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY

Monarchy rests on the practice of dynastic succession, in which the monarch’s child or other relative inherits the throne. In the eighteenth century, well-established monarchs ruled most of Europe and, according to tradition, were obligated to protect and guide their subjects. However, by the mid-1770s, many American colonists believed that George III, the king of Great Britain, had failed to do so. Patriots believed the British monarchy under George III had been corrupted and the king turned into a tyrant who cared nothing for the traditional liberties afforded to members of the British Empire. The disaffection from monarchy explains why a republic appeared a better alternative to the revolutionaries.

American revolutionaries looked to the past for inspiration for their break with the British monarchy and their adoption of a republican form of government. The Roman Republic provided guidance. Much like the Americans in their struggle against Britain, Romans had thrown off monarchy and created a republic in which Roman citizens would appoint or select the leaders who would represent them.

While republicanism offered an alternative to monarchy, it was also an alternative to democracy, a system of government characterized by majority rule, where the majority of citizens have the power to make decisions binding upon the whole. To many revolutionaries, especially wealthy landowners, merchants, and planters, democracy did not offer a good replacement for monarchy. Indeed, conservative Whigs defined themselves in opposition to democracy, which they equated with anarchy, and worked hard to keep democratic tendencies in check.

While many now assume the United States was founded as a democracy, history, as always, is more complicated. Conservative Whigs believed in government by a patrician class, a ruling group composed of a small number of privileged families. Radical Whigs favored broadening the popular participation in political life and pushed for democracy. The great debate after independence was secured centered on this question: Who should rule in the new American republic?

REPUBLICANISM AS A SOCIAL PHILOSOPHY

According to political theory of republicanism, a republic requires its citizens to cultivate virtuous behavior; if the people are virtuous, the republic will survive. If the people become corrupt, the republic will fall. Whether republicanism succeeded or failed in the United States would depend on civic virtue and an educated citizenry. Revolutionary leaders agreed that the ownership of property provided one way to measure an individual’s virtue, arguing that property holders had the greatest stake in society and therefore could be trusted to make decisions for it. By the same token, non-property holders, they believed, should have very little to do with government. In other words, unlike a democracy, in which the mass of non-property holders could exercise the political right to vote, a republic would limit political rights to property holders. In this way, republicanism exhibited a bias toward the elite.

|

|

DEFINING “AMERICAN” |

|

Benjamin Franklin’s Thirteen Virtues for Character Development In the 1780s, Benjamin Franklin carefully defined thirteen virtues to help guide his countrymen in maintaining a virtuous republic. His choice of thirteen is telling since he wrote for the citizens of the thirteen new American republics. These virtues were: “Temperance. Eat not to dullness; drink not to elevation. Silence. Speak not but what may benefit others or yourself; avoid trifling conversation. Order. Let all your things have their places; let each part of your business have its time. Resolution. Resolve to perform what you ought; perform without fail what you resolve. Frugality. Make no expense but to do good to others or yourself; i.e., waste nothing. Industry. Lose no time; be always employ’d in something useful; cut off all unnecessary actions. Sincerity. Use no hurtful deceit; think innocently and justly, and, if you speak, speak accordingly. Justice. Wrong none by doing injuries, or omitting the benefits that are your duty. Moderation. Avoid extremes; forbear resenting injuries so much as you think they deserve. Cleanliness. Tolerate no uncleanliness in body, cloaths, or habitation. Tranquillity. Be not disturbed at trifles, or at accidents common or unavoidable. Chastity. Rarely use venery but for health or offspring, never to dullness, weakness, or the injury of your own or another’s peace or reputation. Humility. Imitate Jesus and Socrates.” |

|

The first president of the United States, George Washington, served as a role model par excellence for the new republic, embodying the exceptional talent and public virtue prized under the political and social philosophy of republicanism. He did not seek to become the new king of America; instead he retired as commander in chief of the Continental Army and returned to his Virginia estate at Mount Vernon to resume his life among the planter elite. He was elected as President and served for two terms (8 years) but refused to serve a third, preferring instead to hand over the Presidency to another man and retire to his family farm. Washington modeled his behavior on that of the Roman aristocrat Cincinnatus, a representative of the patrician or ruling class, who had also retired from public service in the Roman Republic and returned to his estate to pursue agricultural life.

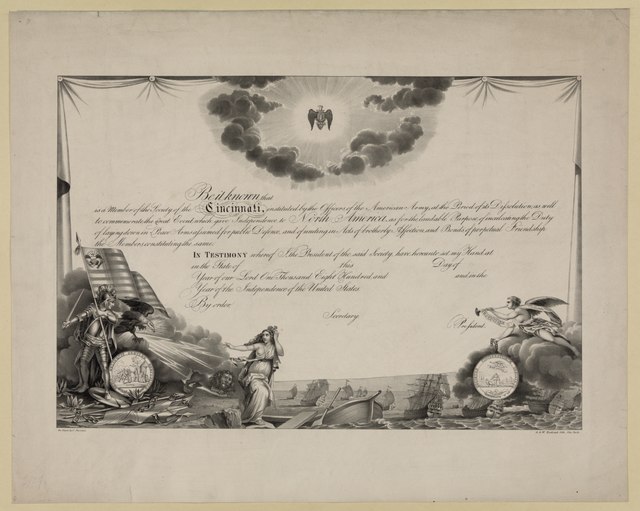

The aristocratic side of republicanism—and the belief that the true custodians of public virtue were those who had served in the military—found expression in the Society of the Cincinnati, of which Washington was the first president general. Founded in 1783, the society admitted only officers of the Continental Army and the French forces, not militia members or minutemen.

This membership certificate for the Society of the Cincinnati commemorates “the great Event which gave Independence to North America.” Source: Wikimedia Commons

4.1 Section Summary

The guiding principle of republicanism was that the people themselves would appoint or select the leaders who would represent them. The debate over how much democracy (majority rule) to incorporate in the governing of the new United States raised questions about who was best qualified to participate in government and have the right to vote. Revolutionary leaders argued that property holders had the greatest stake in society and favored a republic that would limit political rights to property holders. In this way, republicanism exhibited a bias toward the elite. George Washington served as a role model for the new republic, embodying the exceptional talent and public virtue prized in its political and social philosophy.

4.2 How Much Revolutionary Change?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the status of women in the new republic

- Describe the status of nonwhites in the new republic

Elite republican revolutionaries did not envision a completely new society; traditional ideas and categories of race and gender, order and decorum remained firmly entrenched among members of their privileged class. Many Americans rejected the elitist and aristocratic republican order, however, and advocated radical changes. Their efforts represented a groundswell of sentiment for greater equality, a part of the democratic impulse unleashed by the Revolution.

THE STATUS OF WOMEN

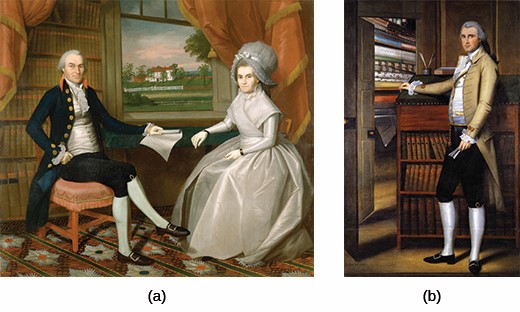

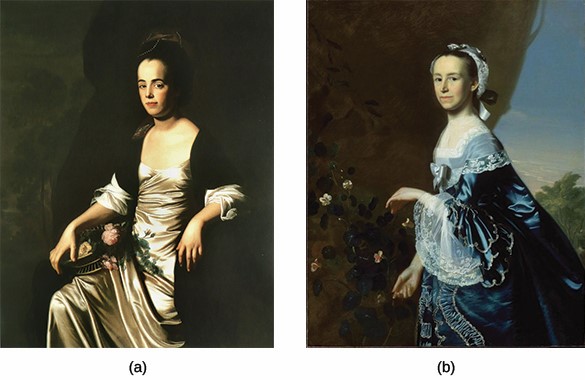

John Singleton Copley’s 1772 portrait of Judith Sargent Murray (a) and 1763 portrait of Mercy Otis Warren (b) show two of America’s earliest advocates for women’s rights. See how their fine silk dresses telegraph their privileged social status. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In eighteenth-century America, as in Great Britain, the legal status of married women was defined as coverture, meaning a married woman (or feme covert) had no legal or economic status independent of her husband. She could not conduct business or buy and sell property. Her husband controlled any property she brought to the marriage, although he could not sell it without her agreement. Married women’s status as femes covert did not change as a result of the Revolution, and wives remained economically dependent on their husbands. The women of the newly independent nation did not call for the right to vote, but some, especially the wives of elite republican statesmen, began to agitate for equality under the law between husbands and wives, and for the same educational opportunities as men.

One privileged member of the revolutionary generation, Mercy Otis Warren, challenged gender assumptions and traditions during the revolutionary era. Born in Massachusetts, Warren actively opposed British reform measures before the outbreak of fighting in 1775 by publishing anti-British works. In 1812, she published a three-volume history of the Revolution, a project she had started in the late 1770s. By publishing her work, Warren stepped out of the female sphere and into the otherwise male dominated sphere of public life.

Another woman inspired by the ideals of the Revolution, Judith Sargent Murray of Massachusetts, advocated women’s economic independence and equal educational opportunities for men and women. Murray, who came from a well-to-do family in Gloucester, questioned why boys were given access to education as a birthright while girls had very limited educational opportunities. She began to publish her ideas about educational equality beginning in the 1780s, arguing that God had made the minds of women and men equal.

Murray’s more radical ideas championed woman’s economic independence. She argued that a woman’s education should be extensive enough to allow her to maintain herself—and her family—if there was no male breadwinner. Indeed, Murray was able to make money of her own from her publications. Her ideas were both radical and traditional, however: Murray also believed that women were much better at raising children and maintaining the morality and virtue of the family than men.

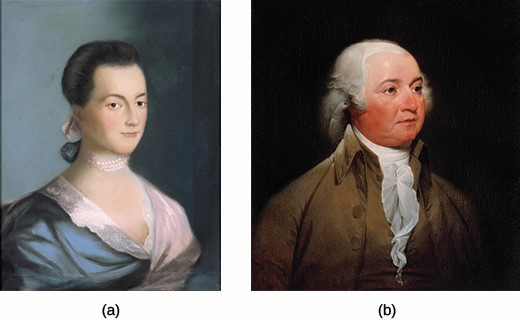

Some women hoped to overturn coverture. From her home in Braintree, Massachusetts, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband, Whig leader John Adams, in 1776, asking him to “remember the ladies” as he worked to write new laws for the country. Abigail Adams ran the family homestead during the Revolution, but she did not have the ability to conduct business without her husband’s consent. Elsewhere in her letter, she lamented the difficulties of running the household when her husband is away. Her frustration undoubtedly grew when she received her husband’s response in which he stated that he found her letter comical. He concluded his letter with these words: “Depend on it, We know better than to repeal our Masculine systems.”

Abigail Adams (a), shown here in a 1766 portrait by Benjamin Blythe, is best remembered for her eloquent letters to her husband, John Adams (b), arguing for equality under the law between husbands and wives. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Overall, the Revolution reconfigured women’s roles by undermining the traditional expectations of wives and mothers, including subservience. In the home, the separate domestic sphere assigned to women, women were expected to practice republican virtues, especially frugality and simplicity. Republican motherhood meant that women, more than men, were responsible for raising good children, instilling in them all the virtue necessary to ensure the survival of the republic. The Revolution also opened new doors to educational opportunities for women.

THE MEANING OF RACE AND SLAVERY

Slavery offered the most glaring contradiction between the idea of equality stated in the Declaration of Independence (“all men are created equal”) and the reality of race relations in the late eighteenth century. By the time of the Revolution, slavery had been firmly in place in America for over one hundred years. In many ways, the Revolution served to reinforce the assumptions about race among white Americans. They viewed the new nation as a white republic; blacks were slaves, and Indians had no place. Racial hatred of blacks increased during the Revolution because many enslaved people fled their white masters for the freedom offered by the British. The same was true for Indians who allied themselves with the British; Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence that separation from the Empire was necessary because George III had incited “the merciless Indian savages” to destroy the white inhabitants on the frontier. Similarly, Thomas Paine argued in Common Sense that Great Britain was guilty of inciting “the Indians and Negroes to destroy us.” For his part, Benjamin Franklin wrote in the 1780s that, in time, alcoholism would wipe out the Indians, leaving the land free for white settlers.

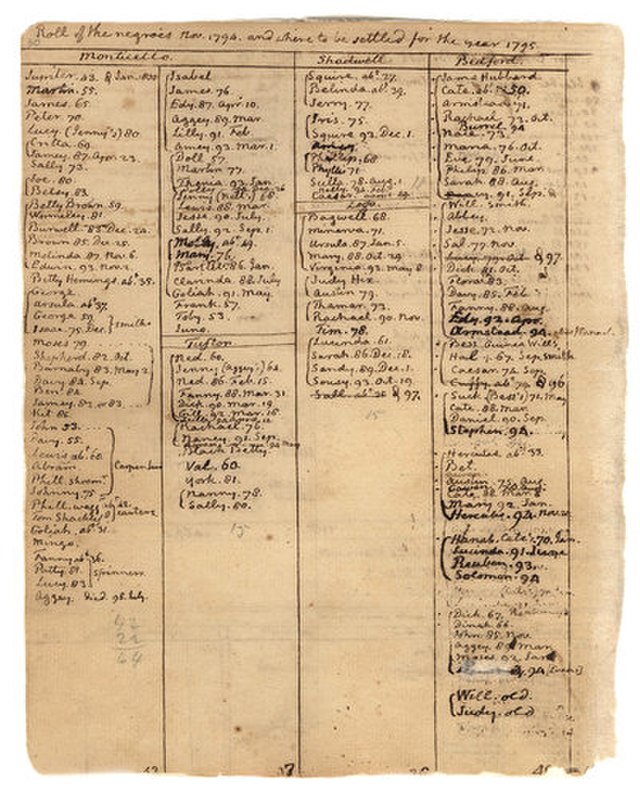

Racism shaped white views of blacks. Although he penned the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson owned more than one hundred slaves, of whom he freed only a few either during his lifetime or in his will. He thought blacks were inferior to whites, dismissing Phillis Wheatley by arguing, “Religion indeed has produced a Phillis Wheatley; but it could not produce a poet.” White slaveholders took their female slaves as mistresses, as Jefferson did with one of his slaves, Sally Hemings (at the age of 15). Together, they had several children.

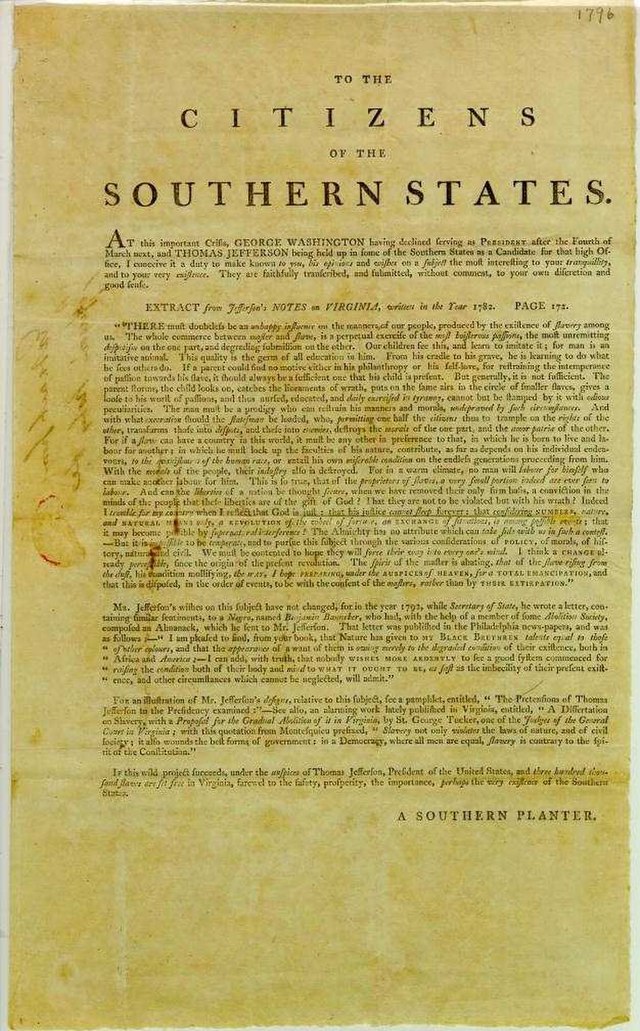

Jefferson understood the contradiction fully, and his writings reveal hard-edged racist assumptions. In his Notes on the State of Virginia in the 1780s, Jefferson urged the end of slavery in Virginia and the removal of blacks from that state. Jefferson envisioned an “empire of liberty” for white farmers and relied on the argument of sending blacks out of the United States, even if doing so would completely destroy the slaveholders’ wealth in their human property. Southern planters strongly objected to Jefferson’s views on abolishing slavery and removing blacks from America. Slaveholders and many other Americans protected and defended the institution.

A page from Thomas Jefferson’s record book, (dated 1795) listing the names of his enslaved people over the years. They numbered roughly 600 in his lifetime, though he only employed about 120 at any one given time. Source: Wikimedia Commons

|

|

MY STORY |

|

Phillis Wheatley: “On Being Brought from Africa to America” Phillis Wheatley was born in Africa in 1753 and sold to the Wheatley family of Boston; her African name is lost to posterity. Although most enslaved people in the eighteenth century had no opportunities to learn to read and write, Wheatley achieved full literacy and went on to become one of the best-known poets of the time, although many doubted her authorship of her poems because of her race. This portrait of Phillis Wheatley from the frontispiece of Poems on various subjects, religious and moral shows the writer at work. Despite her status as an enslaved person, her poems won great renown in America and in Europe.

Wheatley’s poems reflected her deep Christian beliefs. In the poem below, observe how her views on Christianity affect her views on slavery. “Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land, Taught my benighted soul to understand That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too: Once I redemption neither sought nor knew. Some view our sable race with scornful eye, “Their colour is a diabolic dye.” Remember, Christians, Negroes, black as Cain, May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.” —Phillis Wheatley, “On Being Brought from Africa to America” |

|

Freedom

While racial thinking permeated the new country, and slavery existed in all the new states, the ideals of the Revolution generated a movement toward the abolition of slavery. Private manumissions, by which slaveholders freed their slaves, provided one pathway from bondage. Slaveholders in Virginia freed some ten thousand slaves. In Massachusetts, the Wheatley family manumitted Phillis in 1773 when she was twenty-one. Other revolutionaries formed societies dedicated to abolishing slavery. One of the earliest efforts began in 1775 in Philadelphia, where Dr. Benjamin Rush and other Philadelphia Quakers formed what became the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. Similarly, wealthy New Yorkers formed the New York Manumission Society in 1785. This society worked to educate black children and devoted funds to protect free blacks from kidnapping.

Slavery persisted in the North, however, and the example of Massachusetts highlights the complexity of the situation. The 1780 Massachusetts constitution technically freed all enslaved people. Nonetheless, about eleven hundred enslaved people continued to be held in the New England states in 1800. The contradictions illustrate the difference between the letter and the spirit of the laws abolishing slavery in Massachusetts. In all, over thirty-six thousand enslaved people remained in the North, with the highest concentrations in New Jersey and New York. New York only gradually phased out slavery, with the last enslaved people emancipated in the late 1820s.

This 1796 broadside to “the Citizens of the Southern States” by “a Southern Planter” argued that Thomas Jefferson’s advocacy of the emancipation of enslaved people in his Notes on the State of Virginia posed a threat to the safety, the prosperity, and even the existence of the southern states. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Native Americans

The 1783 Treaty of Paris, which ended the war for independence, did not address Native peoples at all. All lands held by the British east of the Mississippi and south of the Great Lakes (except Spanish Florida) now belonged to the new American republic. Though the treaty remained silent on the issue, much of the territory now included in the boundaries of the United States remained under the control of native peoples. Earlier in the eighteenth century, a “middle ground” had existed between powerful native groups in the West and British and French imperial zones, a place where the various groups interacted and accommodated each other. As had happened in the French and Indian War and Pontiac’s Rebellion, the Revolutionary War turned the middle ground into a battle zone that no one group controlled.

During the Revolution, a complex situation existed among Indians. Many villages remained neutral. Some native groups, such as the Delaware, split into factions, with some supporting the British while other Delaware maintained their neutrality. The Iroquois Confederacy, a longstanding alliance of tribes, also split up: the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, and Seneca fought on the British side, while the Oneida and Tuscarora supported the revolutionaries. Ohio River Valley tribes such as the Shawnee, Miami, and Mungo had been fighting for years against colonial expansion west; these groups supported the British. Some native peoples who had previously allied with the French hoped the conflict between the colonies and Great Britain might lead to French intervention and the return of French rule. Few Indians sided with the American revolutionaries, because almost all revolutionaries in the middle ground viewed them as an enemy to be destroyed. This racial hatred toward native peoples found expression in the American massacre of ninety-six Christian Delawares in 1782. Most of the dead were women and children. After the war, the victorious Americans turned a deaf ear to Indian claims to what the revolutionaries saw as their hard-won land, and they moved aggressively to assert control over western New York and Pennsylvania.

RELIGION AND THE STATE

Prior to the Revolution, several colonies had official, tax-supported churches. After the Revolution, some questioned the validity of state-authorized churches; the limitation of public office-holding to those of a particular faith; and the payment of taxes to support churches. In other states, especially in New England where the older Puritan heritage cast a long shadow, religion and state remained intertwined.

During the colonial era in Virginia, the established church had been the Church of England, which did not tolerate Catholics, Baptists, or followers or other religions. In 1786, as a revolutionary response against the privileged status of the Church of England, Virginia’s lawmakers approved the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, which ended the Church of England’s hold and allowed religious liberty. Under the statute, no one could be forced to attend or support a specific church or be prosecuted for his or her beliefs.

Pennsylvania’s original constitution limited officeholders in the state legislature to those who professed a belief in both the Old and the New Testaments. This religious test prohibited Jews from holding that office, as the New Testament is not part of Jewish belief. In 1790, however, Pennsylvania removed this qualification from its constitution. The New England states were slower to embrace freedom of religion. In the former Puritan colonies, the Congregational Church (established by seventeenth-century Puritans) remained the church of most inhabitants. Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire all required the public support of Christian churches.

4.2 Section Summary

After the Revolution, the balance of power between women and men and between whites, blacks, and Indians remained largely unchanged. Yet revolutionary principles, including the call for universal equality in the Declaration of Independence, inspired and emboldened many. Abigail Adams and others pressed for greater rights for women, while the Pennsylvania Abolition Society and New York Manumission Society worked toward the abolition of slavery. Nonetheless, for blacks, women, and native peoples, the revolutionary ideals of equality fell far short of reality. In the new republic, full citizenship—including the right to vote—did not extend to nonwhites or to women.

4.3 Debating Democracy

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the features of the Articles of Confederation

- Analyze the causes and consequences of Shays’ Rebellion

The task of creating republican governments in each of the former colonies, now independent states, presented a new opportunity for American revolutionaries to define themselves anew after casting off British control. On the state and national levels, citizens of the new United States debated who would hold the keys to political power. The states proved to be a laboratory for how much democracy, or majority rule, would be tolerated.

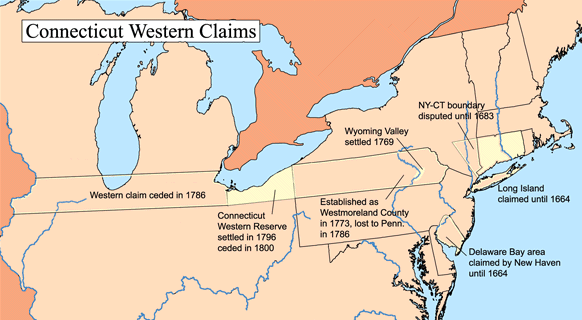

THE ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION

Most revolutionaries pledged their greatest loyalty to their individual states. Recalling the experience of British reform efforts imposed in the 1760s and 1770s, they feared a strong national government and took some time to adopt the Articles of Confederation, the first national constitution. In June 1776, the Continental Congress prepared to announce independence and began to think about the creation of a new government to replace royal authority. Reaching agreement on the Articles of Confederation proved difficult as members of the Continental Congress argued over western land claims. For example, Connecticut, as the map below demonstrates, used its colonial charter to assert its claim to western lands in Pennsylvania and the Ohio Territory.

Members of the Continental Congress also debated what type of representation would be best and tried to figure out how to pay the expenses of the new government. In lieu of creating a new federal government, the Articles of Confederation created a “league of friendship” between the states. Congress readied the Articles in 1777 but did not officially approve them until 1781. The delay of four years illustrates the difficulty of getting the thirteen states to agree on a plan of national government. Citizens viewed their respective states as sovereign republics and guarded their prerogatives against other states.

Passage of any law under the Articles of Confederation proved difficult. It took the consensus of nine states for any measure to pass, and amending the Articles required the consent of all the states, also extremely difficult to achieve. Further, any acts put forward by the Congress were non-binding; states had the option to enforce them or not. This meant that while the Congress had power over Indian affairs and foreign policy, individual states could choose whether or not to comply.

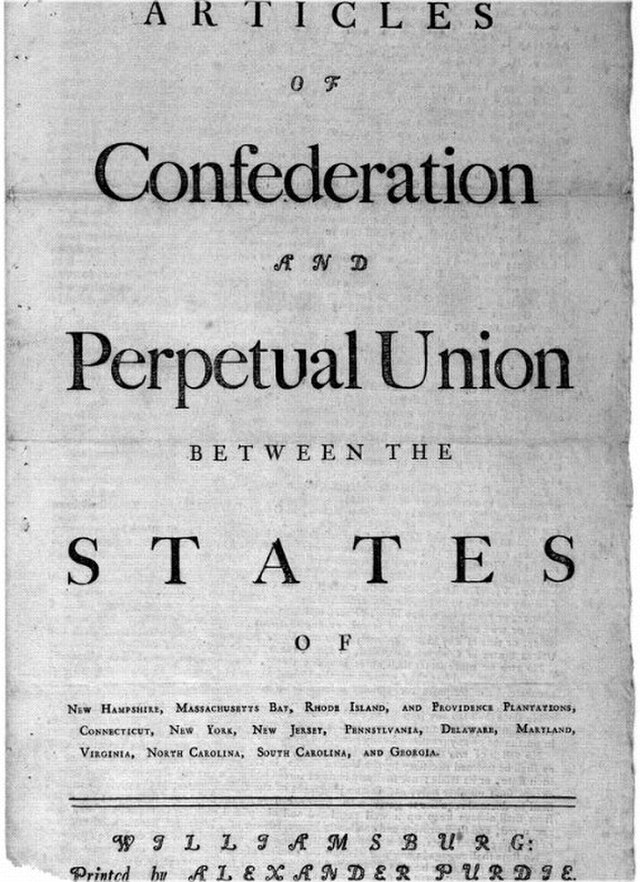

The Articles of Confederation authorized a unicameral legislature, a continuation of the earlier Continental Congress. The people could not vote directly for members of the national Congress; rather, state legislatures decided who would represent the state. In practice, the national Congress was composed of state delegations. There was no president or executive office of any kind, and there was no national judiciary (or Supreme Court) for the United States. Perhaps most importantly, the Articles did not give the federal government to power to tax its citizens. By the 1780s, some members of the Congress were greatly concerned about the financial health of the republic, and they argued that the national government needed greater power, especially the power to tax. This required amending the Articles of Confederation with the consent of all the states.

The first page of the 1777 Articles of Confederation emphasized the “perpetual union” between the states. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Establishing workable foreign and commercial policies under the Articles of Confederation also proved difficult. Each state could decide for itself whether to comply with treaties between the Congress and foreign countries, and there were no means of enforcement. Both Great Britain and Spain understood the weakness of the Confederation Congress, and they refused to make commercial agreements with the United States because they did not believe they would be enforced. Without stable commercial policies, American exporters found it difficult to do business, and British goods flooded U.S. markets in the 1780s, in a repetition of the economic imbalance that existed before the Revolutionary War.

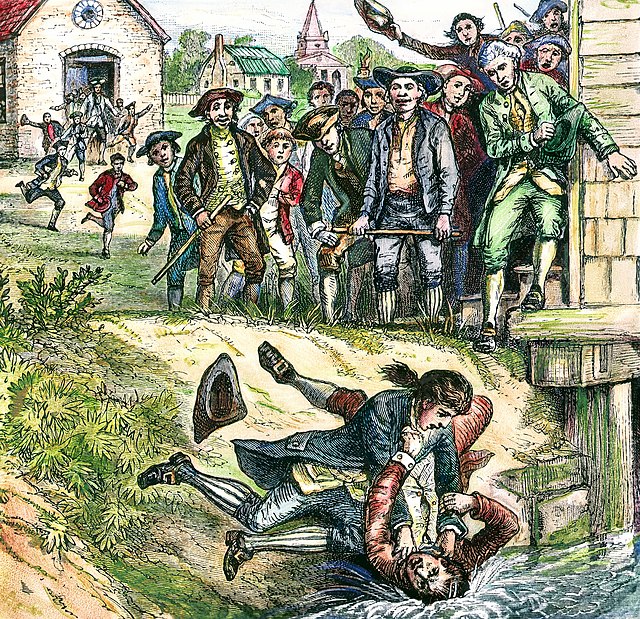

SHAYS’ REBELLION

In the 1780s, the newly formed nation faced great financial challenges. Each state had issued large amounts of paper money, and, in the aftermath of the Revolution, widespread internal devaluation of that currency occurred as many lost confidence in the value of state paper money and the Continental dollar. A period of extreme inflation set in. The economic crisis came to a head in 1786 and 1787 in western Massachusetts, where farmers were in a difficult position: they faced high taxes and debts, which they found nearly impossible to pay with the worthless state and Continental paper money. To the indebted farmers, the situation in the 1780s seemed hauntingly familiar; the revolutionaries had routed the British, but a new form of seemingly corrupt and self-serving government had replaced them.

In 1786, the state legislature refused to address the petitioners’ requests. The farmers responded by taking up arms and closing courthouses across the state to prevent foreclosure (seizure of land in lieu of overdue loan payments) on farms in debt. Many of the rebels were veterans of the war for independence, including Captain Daniel Shays from Pelham. Although Shays was only one of many former officers in the Continental Army who took part in the revolt, authorities in Boston singled him out as a ringleader, and the uprising became known as Shays’ Rebellion.

The climax of Shays’ Rebellion came in January 1787, when the rebels attempted to seize the federal armory in Springfield, Massachusetts. A force loyal to the state defeated them there. Although Shays’ Rebellion resulted in only eighteen deaths, the uprising had lasting effects. To men of property, mostly conservative Whigs, Shays’ Rebellion strongly suggested the republic was falling into anarchy and chaos. The other twelve states had faced similar economic and political difficulties, and continuing problems seemed to indicate that on a national level, a democratic impulse was driving the population. Shays’ Rebellion convinced George Washington to come out of retirement and lead the convention called for by Alexander Hamilton to amend the Articles of Confederation in order to deal with insurgencies like the one in Massachusetts and provide greater stability in the United States.

In this painting by an unknown artist, a Shays’ protestor attacks a tax collector. Source: Wikimedia Commons

4.3 Section Summary

The late 1770s and 1780s witnessed one of the most creative political eras as each state drafted its own constitution. The Articles of Confederation, a weak national league among the states, reflected the dominant view that power should be located in the states and not in a national government. However, neither the state governments nor the Confederation government could solve the enormous economic problems resulting from the long and costly Revolutionary War. The economic crisis led to Shays’ Rebellion by residents of western Massachusetts, and to the decision to revise the Confederation government.

4.4 The Constitutional Convention and Federal Constitution

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the central issues of the 1787 Constitutional Convention and their solutions

- Describe the conflicts over the ratification of the federal constitution

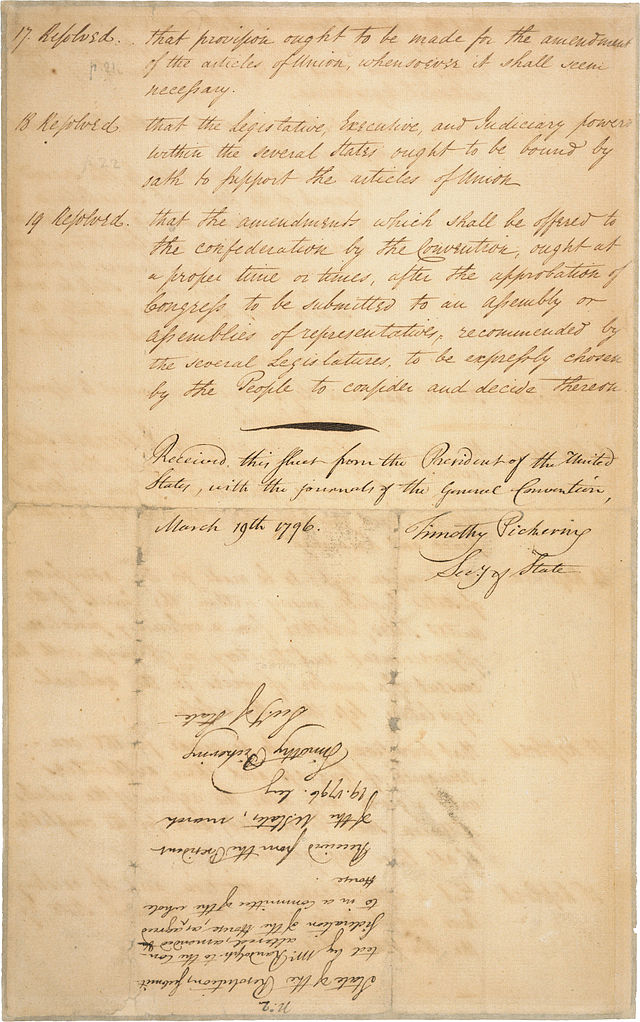

The economic problems that plagued the thirteen states of the Confederation set the stage for the creation of a strong central government under a federal constitution. Although the original purpose of the convention was to amend the Articles of Confederation, some—though not all—delegates moved quickly to create a new framework for a more powerful national government. This proved extremely controversial. Those who attended the convention split over the issue of robust, centralized government and questions of how Americans would be represented in the federal government. Those who opposed the proposal for a stronger federal government argued that such a plan betrayed the Revolution by limiting the voice of the American people.

THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION

In February 1787, in the wake of the uprising in western Massachusetts, the Confederation Congress authorized a Convention in Philadelphia. The stated purpose of the Philadelphia Convention in 1787 was to amend the Articles of Confederation. Very quickly, however, the attendees decided to create a new framework for a national government. That framework became the United States Constitution, and the Philadelphia convention became known as the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Fifty-five men met in Philadelphia in secret; historians know of the proceedings only because James Madison kept careful notes of what transpired. The delegates knew that what they were doing would be controversial; Rhode Island refused to send delegates, and New Hampshire’s delegates arrived late. Two delegates from New York, Robert Yates and John Lansing, left the convention when it became clear that the Articles were being put aside and a new plan of national government was being drafted. They did not believe the delegates had the authority to create a strong national government.

THE QUESTION OF REPRESENTATION

One issue that the delegates in Philadelphia addressed was the way in which representatives to the new national government would be chosen. Would individual citizens be able to elect representatives? Would representatives be chosen by state legislatures? How much representation was appropriate for each state?

James Madison put forward a proposition known as the Virginia Plan, which called for a strong national government that could overturn state laws. The plan featured a bicameral or two-house legislature, with an upper and a lower house. The people of the states would elect the members of the lower house, whose numbers would be determined by the population of the state. State legislatures would send delegates to the upper house. The number of representatives in the upper chamber would also be based on the state’s population. This proportional representation gave the more populous states, like Virginia, more political power.

James Madison’s Virginia Plan, shown here, proposed a strong national government with proportional state representation. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Virginia Plan’s call for proportional representation alarmed the representatives of the smaller states. William Paterson introduced a New Jersey Plan to counter Madison’s scheme, proposing that all states have equal votes in a unicameral national legislature. He also addressed the economic problems of the day by calling for the Congress to have the power to regulate commerce, to raise revenue through taxes on imports and through postage, and to enforce Congressional requisitions from the states.

Roger Sherman from Connecticut offered a compromise to break the deadlock over the thorny question of representation. His Connecticut Compromise, also known as the Great Compromise, outlined a different bicameral legislature in which the upper house, the Senate, would have equal representation for all states; each state would be represented by two senators chosen by the state legislatures. Only the lower house, the House of Representatives, would have proportional representation.

THE QUESTION OF SLAVERY

The question of slavery stood as a major issue at the Constitutional Convention because enslavers wanted enslaved people to be counted along with whites, termed “free inhabitants,” when determining a state’s total population. This, in turn, would augment the number of representatives accorded to those states in the lower house. Some northerners, however, such as New York’s Gouverneur Morris, hated slavery and did not even want the term included in the new national plan of government. Slaveholders argued that slavery imposed great burdens upon them and that, because they carried this liability, they deserved special consideration; slaves needed to be counted for purposes of representation.

The men who gathered at the Convention agreed upon a compromise (known as the three-fifths compromise): each enslaved person would be counted as three-fifths of a person. Northerners agreed to the three-fifths compromise because the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, passed by the Confederation Congress, banned slavery in the future states of the northwest. Northern delegates felt this ban balanced political power between states with enslaved people and those without. The three-fifths compromise gave an advantage to enslavers; they added three-fifths of their human property to their state’s population, allowing them to send representatives based in part on the number of enslaved people they held.

THE QUESTION OF DEMOCRACY

Many of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention had serious reservations about democracy, which they believed promoted anarchy. To allay these fears, the Constitution blunted democratic tendencies that appeared to undermine the republic. Thus, to avoid giving the people too much direct power, the delegates made certain that senators were chosen by the state legislatures, not elected directly by the people (direct elections of senators came with the Seventeenth Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1913). As an additional safeguard, the delegates created the Electoral College, the mechanism for choosing the president. Under this plan, each state has a certain number of electors, which is its number of senators (two) plus its number of representatives in the House of Representatives. Critics, then as now, argue that this process prevents the direct election of the president.

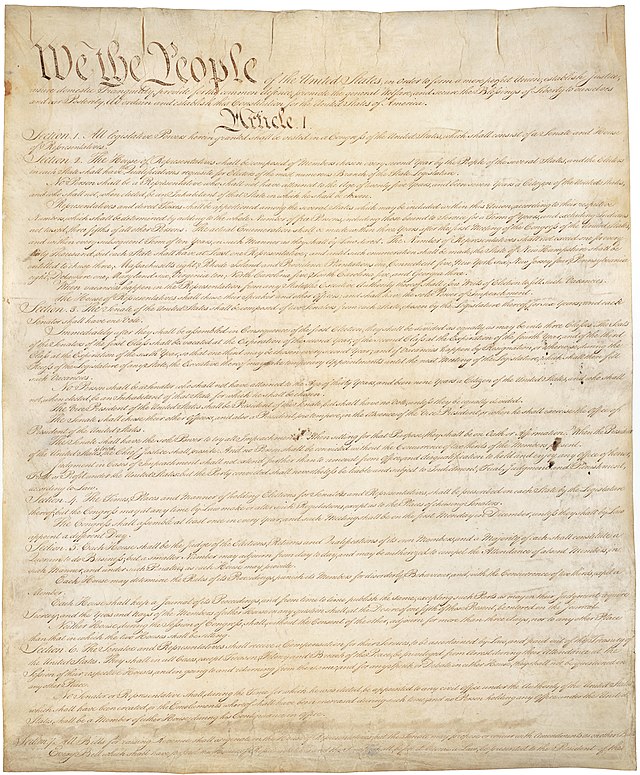

The first page of the 1787 United States Constitution, shown here, begins: “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.” Source: Wikimedia Commons

The U.S. Constitution, written in 1787, establishes the framework of the federal government and protects individual rights. When reading the Constitution, start by focusing on the Preamble—it gives you a sense of the document’s purpose. As you move through the Articles and Amendments, take your time. Look up unfamiliar words, pay attention to the structure of government it creates, and notice how power is both granted and limited. It’s helpful to ask yourself how each part relates to what you see in government today.

To read the full Constitution, click here.

4.4 Section Summary

The economic crisis of the 1780s, shortcomings of the Articles of Confederation, and outbreak of Shays’ Rebellion spurred delegates from twelve of the thirteen states to gather for the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Although the stated purpose of the convention was to modify the Articles of Confederation, their mission shifted to the building of a new, strong federal government. Federalists like James Madison and Alexander Hamilton led the charge for a new United States Constitution, the document that endures as the oldest written constitution in the world, a testament to the work done in 1787.

4.5 Competing Visions: Federalists and Democratic-Republicans

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the competing visions of the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans

- Identify the protections granted to citizens under the Bill of Rights

- Explain Alexander Hamilton’s financial programs as secretary of the treasury

The delegates to the Constitutional Convention had decided that in order for the new national government to be implemented, each state must first hold a special ratifying convention. When nine of the thirteen had approved the plan, the constitution would go into effect.

When the American public learned of the new constitution, opinions were deeply divided, but most people were opposed. To salvage their work in Philadelphia, the architects of the new national government began a campaign to sway public opinion in favor of their blueprint for a strong central government. In the fierce debate that erupted, the two sides articulated contrasting visions of the American republic and of democracy. Supporters of the 1787 Constitution, known as Federalists, made the case that a centralized republic provided the best solution for the future. Those who opposed it, known as Anti-Federalists, argued that the Constitution would consolidate all power in a national government, robbing the states of the power to make their own decisions. To them, the Constitution appeared to mimic the old corrupt and centralized British regime, under which a far-off government made the laws. Anti-Federalists argued that wealthy aristocrats would run the new national government, and that the elite would not represent ordinary citizens; the rich would monopolize power and use the new government to formulate policies that benefited their class—a development that would also undermine local state elites. They also argued that the Constitution did not contain a bill of rights. The Federalists, particularly John Jay, Alexander Hamilton, and James Madison, put their case to the public in a famous series of essays known as The Federalist Papers. These were first published in New York and subsequently republished elsewhere in the United States.

|

|

DEFINING “AMERICAN” |

|

James Madison on the Benefits of Republicanism The tenth essay in The Federalist Papers, often called Federalist No. 10, is one of the most famous. Written by James Madison (whose official portrait is below), it addresses the problems of political parties (“factions”). Madison argued that there were two approaches to solving the problem of political parties: a republican government and a democracy. He argued that a large republic provided the best defense against what he viewed as the tumult of direct democracy. Compromises would be reached in a large republic and citizens would be represented by representatives of their own choosing. “From this view of the subject, it may be concluded, that a pure Democracy, by which I mean a Society consisting of a small number of citizens, who assemble and administer the Government in person, can admit of no cure for the mischiefs of faction. A common passion or interest will, in almost every case, be felt by a majority of the whole; a communication and concert result from the form of Government itself; and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party, or an obnoxious individual. Hence it is, that such Democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security, or the rights of property; and have in general been as short in their lives, as they have been violent in their deaths. … A Republic, by which I mean a Government in which the scheme of representation takes place, opens a different prospect, and promises the cure for which we are seeking. Let us examine the points in which it varies from pure Democracy, and we shall comprehend both the nature of the cure, and the efficacy which it must derive from the Union. The two great points of difference, between a Democracy and a Republic, are, first, the delegation of the Government, in the latter, to a small number of citizens elected by the rest: Secondly, the greater number of citizens, and greater sphere of country, over which the latter may be extended.”

|

|

Including all the state ratifying conventions around the country, a total of fewer than two thousand men voted on whether to adopt the new plan of government. In the end, the Constitution only narrowly won approval. In New York, the vote was thirty in favor to twenty-seven opposed. In Massachusetts, the vote to approve was 187 to 168, and some claim supporters of the Constitution resorted to bribes in order to ensure approval. Virginia ratified by a vote of eighty-nine to seventy-nine, and Rhode Island by thirty-four to thirty-two. The opposition to the Constitution reflected the fears that a new national government, much like the British monarchy, created too much centralized power and, as a result, deprived citizens in the various states of the ability to make their own decisions.

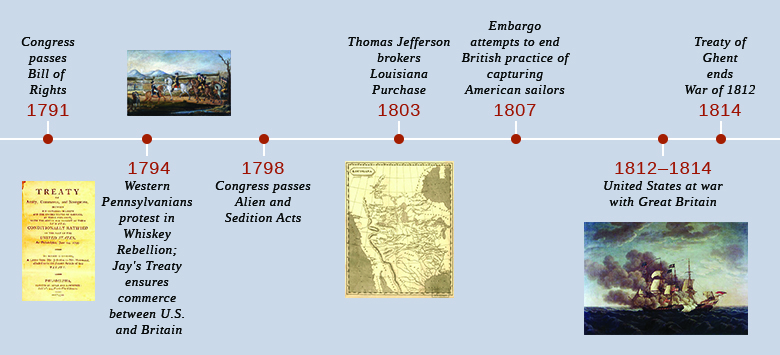

In June 1788, New Hampshire became the ninth state to ratify the federal Constitution, and the new plan for a strong central government went into effect. Elections for the first U.S. Congress were held in 1788 and 1789, and members took their seats in March 1789. In a reflection of the trust placed in him as the personification of republican virtue, George Washington became the first president in April 1789. John Adams served as his vice president; the pairing of a representative from Virginia (Washington) with one from Massachusetts (Adams) symbolized national unity. Nonetheless, political divisions quickly became apparent. Washington and Adams represented the Federalist Party, which generated a backlash among those who resisted the new government’s assertions of federal power.

FEDERALISTS IN POWER

Though the Revolution had overthrown British rule in the United States, supporters of the 1787 federal constitution, known as Federalists, adhered to a decidedly British notion of social hierarchy. For them, political participation continued to be linked to property rights, which barred many citizens from voting or holding office. Federalists did not believe the Revolution had changed the traditional social roles between women and men, or between whites and other races. They did believe in clear distinctions in rank and intelligence. To these supporters of the Constitution, the idea that all were equal appeared ludicrous. Women, blacks, and native peoples, they argued, had to know their place as secondary to white male citizens. Attempts to impose equality, they feared, would destroy the republic. The United States was not created to be a democracy.

The architects of the Constitution committed themselves to leading the new republic, and they held a majority among the members of the new national government. Indeed, as expected, many assumed the new executive posts the first Congress created. The nation elected its first President, George Washington, in 1789. Washington appointed Alexander Hamilton, a leading Federalist, as secretary of the treasury. For secretary of state, he chose Thomas Jefferson. For secretary of war, he appointed Henry Knox, who had served with him during the Revolutionary War. Edmond Randolph, a Virginia delegate to the Constitutional Convention, was named attorney general. In July 1789, Congress also passed the Judiciary Act, creating a Supreme Court of six justices headed by those who were committed to the new national government.

|

|

AMERICANA |

|

The Art of Ralph Earl Ralph Earl was an eighteenth-century American artist, born in Massachusetts, who remained loyal to the British during the Revolutionary War. He fled to England in 1778, but he returned to New England in the mid-1780s and began painting portraits of leading Federalists. His portrait of Connecticut Federalist Oliver Ellsworth and his wife Abigail (a) conveys the world as Federalists liked to view it: an orderly landscape administered by men of property and learning. His portrait of dry goods merchant Elijah Boardman (b) shows Boardman as well-to-do and highly cultivated; his books include the works of Shakespeare and Milton.

|

|

THE BILL OF RIGHTS

Many Americans opposed the 1787 Constitution because it seemed a dangerous concentration of centralized power that threatened the rights and liberties of ordinary U.S. citizens. These opponents united in demanding protection for individual rights, and several states made the passing of a bill of rights a condition of their acceptance of the Constitution. Rhode Island and North Carolina rejected the Constitution because it did not already have this specific bill of rights. Federalists followed through on their promise to add such a bill in 1789, when Virginia Representative James Madison introduced, and Congress approved the Bill of Rights. Adopted in 1791, the bill consisted of the first ten amendments to the Constitution and outlined many of the personal rights state constitutions already guaranteed.

|

Table 4.1 Rights Protected by the First Ten Amendments |

|

|

Amendment 1 |

Right to freedoms of religion and speech; right to assemble and to petition the government for redress of grievances |

|

Amendment 2 |

Right to keep and bear arms to maintain a well-regulated militia |

|

Amendment 3 |

Right not to house soldiers during time of war |

|

Amendment 4 |

Right to be secure from unreasonable search and seizure |

|

Amendment 5 |

Rights in criminal cases, including to due process and indictment by grand jury for capital crimes, as well as the right not to testify against oneself |

|

Amendment 6 |

Right to a speedy trial by an impartial jury |

|

Amendment 7 |

Right to a jury trial in civil cases |

|

Amendment 8 |

Right not to face excessive bail or fines, or cruel and unusual punishment |

|

Amendment 9 |

Rights retained by the people, even if they are not specifically enumerated by the Constitution |

|

Amendment 10 |

States’ rights to powers not specifically delegated to the federal government |

|

|

|

When the U.S. Constitution was first drafted, many Americans were concerned that it gave too much power to the federal government without offering clear protections for individual liberties. The first ten amendments—known as the Bill of Rights—were added in 1791 to address those concerns. They reflect both longstanding fears of tyranny and a growing commitment to protecting individual freedom within a constitutional system.

As you read, consider the following: Which rights are given priority in the first ten amendments? How do these protections reflect the political debates of the 1780s? What do the amendments suggest about the relationship between the individual and the state? And how have interpretations of these rights evolved over time?

Read the Bill of Rights.

The state of Georgia, like all U.S. states, has its own constitution—and its own bill of rights. Article I of the Georgia Constitution contains a wide-ranging list of rights and protections that both echo and expand upon the federal version. First adopted in 1777 and revised multiple times since, Georgia’s constitutional tradition reflects both its revolutionary origins and its evolving political identity.

As you read, consider the following: Which rights in Georgia’s Bill of Rights are also found in the U.S. Bill of Rights? What rights or protections appear in the Georgia Constitution that are not included in the federal version? How does Georgia’s Bill of Rights reflect concerns unique to state governance? What language or provisions suggest an emphasis on local control, individual responsibility, or public morality? Why might it matter that states have their own constitutions and bills of rights in addition to the U.S. Constitution?

Read the Georgia Bill of Rights (Article I of the 1983 Constitution).

ALEXANDER HAMILTON’S PROGRAM

President Washington appointed Alexander Hamilton to be his secretary of the treasury. Hamilton was an ardent nationalist who believed a strong federal government could solve many of the new country’s financial ills. In the early 1790s, he created the foundation for the U.S. financial system by calling for the creation of a national bank and government support for industry. He believed that a robust federal government would provide a solid financial foundation for the country. The United States operated with a flurry of different notes from multiple state banks and no coherent regulation. By proposing that the new national bank buy up large volumes of state bank notes and demanding their conversion into gold, Hamilton especially wanted to discipline those state banks that issued paper money irresponsibly. To that end, he delivered his “Report on a National Bank” in December 1790, proposing a Bank of the United States, an institution modeled on the Bank of England. The bank would issue loans to American merchants and bills of credit (federal bank notes that would circulate as money) while serving as a repository of government revenue from the sale of land. Hamilton also understood the importance of promoting domestic manufacturing so the new United States would no longer have to rely on imported manufactured goods. To break from the old colonial system, Hamilton therefore advocated tariffs on all foreign imports to stimulate the production of American-made goods. To promote domestic industry further, he proposed federal subsidies to American industries. Like all of Hamilton’s programs, the idea of government involvement in the development of American industries was new.

With the support of Washington, the entire Hamiltonian economic program received the necessary support in Congress to be implemented. In the long run, Hamilton’s financial program helped to rescue the United States from its state of near bankruptcy in the late 1780s. His initiatives marked the beginning of an American capitalism, making the republic creditworthy, promoting commerce, and setting for the nation a solid financial foundation. His policies also facilitated the growth of the stock market, as U.S. citizens bought and sold the federal government’s interest-bearing certificates.

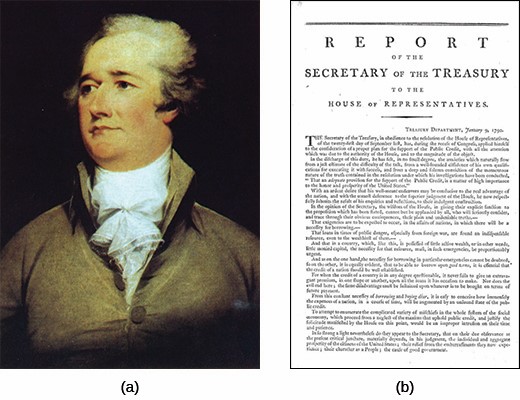

As the first secretary of the treasury, Alexander Hamilton (a), shown here in a 1792 portrait by John Trumbull, released the “Report on Public Credit” (b) in January 1790. Source: Wikimedia Commons

THE DEMOCRATIC-REPUBLICAN PARTY AND THE FIRST PARTY SYSTEM

James Madison and Thomas Jefferson were convinced that the federal government had overstepped its authority by adopting the treasury secretary’s plan. They argued that it turned the reins of government over to the class of speculators who profited at the expense of hardworking citizens.

Jefferson, who had returned to the United States in 1790 after serving as a diplomat in France, tried unsuccessfully to convince Washington to block the creation of a national bank. He also took issue with what he perceived as favoritism given to commercial classes in the principal American cities. He thought urban life widened the gap between the wealthy few and an underclass of landless poor workers who, because of their oppressed condition, could never be good republican property owners. Rural areas, in contrast, offered far more opportunities for property ownership and virtue. In 1783 Jefferson wrote, “Those who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God, if ever he had a chosen people.” Jefferson believed that self-sufficient, property-owning republican citizens or yeoman farmers held the key to the success and longevity of the American republic. (As a creature of his times, he did not envision a similar role for either women or nonwhite men.) To him, Hamilton’s program seemed to encourage economic inequalities and work against the ordinary American yeoman.

Men who felt the domestic policies of the Washington administration were designed to enrich the few while ignoring everyone else formed Democratic-Republican societies. Democratic-Republicans championed limited government. Their fear of centralized power originated in the experience of the 1760s and 1770s when the distant, overbearing, and seemingly corrupt British Parliament attempted to impose its will on the colonies. To opponents, the Federalists promoted aristocracy and a monarchical government—a betrayal of what many believed to be the goal of the American Revolution.

While wealthy merchants and planters formed the core of the Federalist leadership, members of the Democratic-Republican societies in cities like Philadelphia and New York came from the ranks of artisans. These citizens saw themselves as acting in the spirit of 1776, this time not against the haughty British but by what they believed to have replaced them—a commercial class with no interest in the public good. Their political efforts against the Federalists were a battle to preserve republicanism, to promote the public good against private self-interest. They published their views, held meetings to voice their opposition, and sponsored festivals and parades. Some members of northern Democratic-Republican clubs denounced slavery as well.

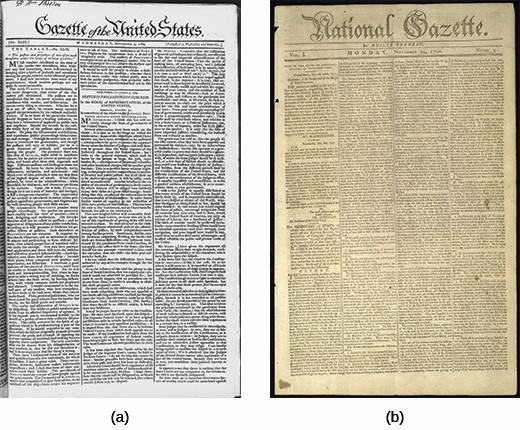

Here, the front page of the Federalist Gazette of the United States from September 9, 1789 (a), is shown beside that of the oppositional National Gazette from November 14, 1791 (b). The Gazette of the United States featured articles, sometimes written pseudonymously or anonymously, from leading Federalists like Alexander Hamilton and John Adams. The National Gazette was founded two years later to counter their political influence.

DEFINING CITIZENSHIP

While questions regarding the proper size and scope of the new national government created a divide among Americans and gave rise to political parties, a consensus existed among men on the issue of who qualified and who did not qualify as a citizen. The 1790 Naturalization Act defined citizenship in stark racial terms. To be a citizen of the American republic, an immigrant had to be a “free white person” of “good character.” By excluding enslaved people, free blacks, Indians, and Asians from citizenship, the act laid the foundation for the United States as a republic of white men.

4.5 Section Summary

While they did not yet constitute distinct political parties, Federalists and Anti-Federalists, shortly after the Revolution, found themselves at odds over the Constitution and the power that it concentrated in the federal government. While many of the Anti-Federalists’ fears were assuaged by the adoption of the Bill of Rights in 1791, the early 1790s nevertheless witnessed the rise of two political parties: the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. These rival political factions began by defining themselves in relationship to Hamilton’s financial program, a debate that exposed contrasting views of the proper role of the federal government. By championing Hamilton’s bold financial program, Federalists, including President Washington, made clear their intent to use the federal government to stabilize the national economy and overcome the financial problems that had plagued it since the 1780s. Members of the Democratic-Republican opposition, however, deplored the expanded role of the new national government. They argued that the Constitution did not permit the treasury secretary’s expansive program and worried that the new national government had assumed powers it did not rightfully possess. Only on the question of citizenship was there broad agreement: only free, white males who met taxpayer or property qualifications could cast ballots as full citizens of the republic.

4.6 The New American Republic

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the major foreign and domestic uprisings of the early 1790s

- Explain the effect of these uprisings on the political system of the United States

The colonies’ alliance with France proved crucial in their victory against the British, and during the 1780s France and the new United States enjoyed a special relationship. Together they had defeated their common enemy, Great Britain. But despite this shared experience, American opinions regarding France diverged sharply in the 1790s when France underwent its own revolution. Democratic-Republicans seized on the French revolutionaries’ struggle against monarchy as the welcome harbinger of a larger republican movement around the world. To the Federalists, however, the French Revolution represented pure anarchy, especially after the execution of the French king in 1793. Along with other foreign and domestic uprisings, the French Revolution helped harden the political divide in the United States in the early 1790s.

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

The French Revolution, which began in 1789, further split American thinkers into different ideological camps, deepening the political divide between Federalists and their Democratic-Republican foes. At first, in 1789 and 1790, the revolution in France appeared to most in the United States as part of a new chapter in the rejection of corrupt monarchy, a trend inspired by the American Revolution. A constitutional monarchy replaced the absolute monarchy of Louis XVI in 1791, and in 1792, France was declared a republic. Republican liberty, the creed of the United States, seemed to be ushering in a new era in France. Indeed, the American Revolution served as an inspiration for French revolutionaries.

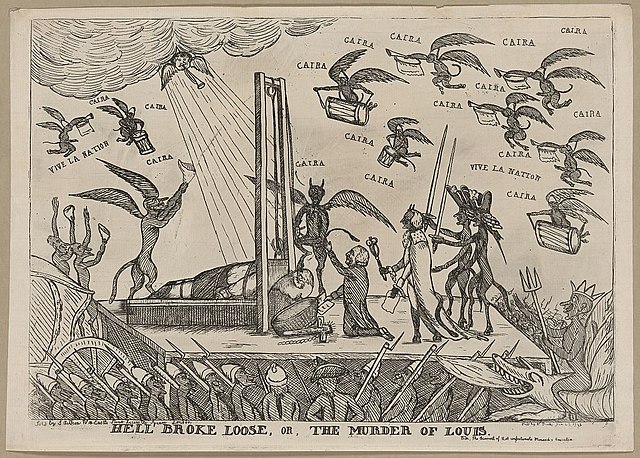

The events of 1793 and 1794 challenged the simple interpretation of the French Revolution as a happy chapter in the unfolding triumph of republican government over monarchy. The French king was executed in January 1793, and the next two years became known as the Terror, a period of extreme violence against perceived enemies of the revolutionary government. Revolutionaries advocated direct representative democracy, dismantled Catholicism, replaced that religion with a new philosophy known as the Cult of the Supreme Being, renamed the months of the year, and relentlessly employed the guillotine against their enemies. Federalists viewed these excesses with growing alarm, fearing that the radicalism of the French Revolution might infect the minds of citizens at home. Democratic-Republicans interpreted the same events with greater optimism, seeing them as a necessary evil of eliminating the monarchy and aristocratic culture that supported the privileges of a hereditary class of rulers.

An image from anti-French British publication depicts the beheading of Louis XVI during the French Revolution. The violence of the revolutionary French horrified many in the United States—especially Federalists, who saw it as an example of what could happen when the mob gained political control and instituted direct democracy.

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION’S CARIBBEAN LEGACY

Unlike the American Revolution, which ultimately strengthened the institution of slavery and the powers of American slaveholders, the French Revolution inspired slave rebellions in the Caribbean, including a 1791 slave uprising in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti). Thousands of enslaved people joined together to overthrow the brutal system of slavery. They took control of a large section of the island, burning sugar plantations and killing the white planters who had forced them to labor under the lash.

In 1794, French revolutionaries abolished slavery in the French empire, and both Spain and England attacked Saint-Domingue, hoping to add the colony to their own empires. Toussaint L’Ouverture, a former domestic enslaved person, emerged as the leader in the fight against Spain and England to secure a Haiti free of slavery and further European colonialism. Because revolutionary France had abolished slavery, Toussaint aligned himself with France, hoping to keep Spain and England at bay.

Events in Haiti further complicated the partisan wrangling in the United States. White refugee planters from Haiti and other French West Indian islands, along with enslaved and free people of color, left the Caribbean for the United States and for Louisiana, which at the time was held by Spain. The presence of these French migrants raised fears, especially among Federalists, that they would bring the contagion of French radicalism to the United States. In addition, the idea that the French Revolution could inspire a successful slave uprising just off the American coastline filled southern whites and enslavers with horror.

An 1802 portrait shows Toussaint L’Ouverture, “Chef des Noirs Insurgés de Saint Domingue” (“Leader of the Black Insurgents of Saint Domingue”), mounted and armed in an elaborate uniform. Source: Wikimedia Commons

THE WHISKEY REBELLION

While the wars in France and the Caribbean divided American citizens, a major domestic test of the new national government came in 1794 over the issue of a tax on whiskey, an important part of Hamilton’s financial program. In 1791, Congress had authorized a tax of 7.5 cents per gallon of whiskey and rum. Although most citizens paid without incident, trouble erupted in four western Pennsylvania counties in an uprising known as the Whiskey Rebellion where poor farmers refused to pay the tax in the spring and summer months of 1794.

Like the Sons of Liberty before the American Revolution, the whiskey rebels used violence and intimidation to protest policies they saw as unfair. They tarred and feathered federal officials, intercepted the federal mail, and intimidated wealthy citizens. With their emphasis on personal freedoms, the whiskey rebels aligned themselves with the Democratic-Republican Party. They saw the tax as part of a larger Federalist plot to destroy their republican liberty and, in its most extreme interpretation, turn the United States into a monarchy. The federal government lowered the tax, but when federal officials tried to subpoena those distillers who remained intractable, trouble escalated. President Washington responded by creating a thirteen-thousand-man militia, drawn from several states, to put down the rebellion. This force made it known, both domestically and to the European powers that looked on in anticipation of the new republic’s collapse, that the national government would do everything in its power to ensure the survival of the United States.

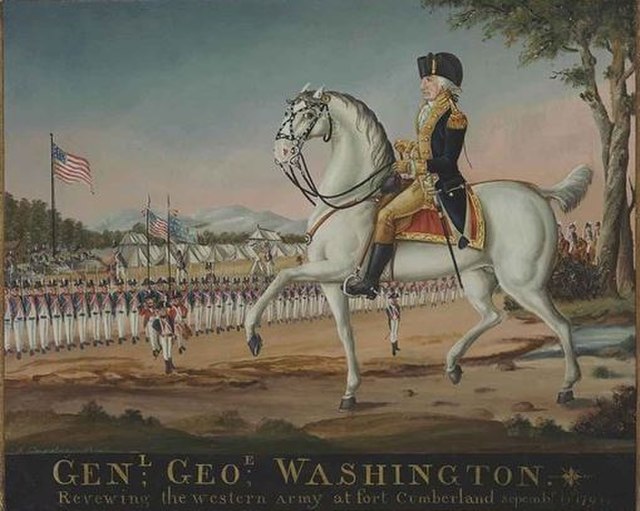

This painting, attributed to Frederick Kemmelmeyer, depicts the massive force George Washington led to put down the Whiskey Rebellion of the previous year. Federalists made clear they would not tolerate mob action. Source: Wikimedia Commons

|

|

DEFINING “AMERICAN” |

|

Alexander Hamilton: “Shall the majority govern or be governed?” Alexander Hamilton frequently wrote persuasive essays under pseudonyms, like “Tully,” as he does here. In this 1794 essay, Hamilton denounces the whiskey rebels and majority rule. “It has been observed that the means most likely to be employed to turn the insurrection in the western country to the detriment of the government, would be artfully calculated among other things ‘to divert your attention from the true question to be decided.’ Let us see then what is this question. It is plainly this—shall the majority govern or be governed? shall the nation rule, or be ruled? shall the general will prevail, or the will of a faction? shall there be government, or no government? . . . The Constitution you have ordained for yourselves and your posterity contains this express clause, ‘The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts, and Excises, to pay the debts, and provide for the common defence and general welfare of the United States.’ You have then, by a solemn and deliberate act, the most important and sacred that a nation can perform, pronounced and decreed, that your Representatives in Congress shall have power to lay Excises. You have done nothing since to reverse or impair that decree. . . . But the four western counties of Pennsylvania, undertake to rejudge and reverse your decrees, you have said, ‘The Congress shall have power to lay Excises.’ They say, ‘The Congress shall not have this power.’ . . . There is no road to despotism more sure or more to be dreaded than that which begins at anarchy.” —Alexander Hamilton’s “Tully No. II” for the American Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia, August 26, 1794 |

|

WASHINGTON’S INDIAN POLICY

Relationships with Indians were a significant problem for Washington’s administration, but one on which white citizens agreed: Indians stood in the way of white settlement and, as the 1790 Naturalization Act made clear, were not citizens. After the War of Independence, white settlers poured into lands west of the Appalachian Mountains. As a result, from 1785 to 1795, a state of war existed on the frontier between these settlers and the Indians who lived in the Ohio territory. In both 1790 and 1791, the Shawnee and Miami had defended their lands against the whites who arrived in greater and greater numbers from the East. In response, Washington appointed General Anthony Wayne to bring the Western Confederacy—a loose alliance of tribes—to heel. In 1794, at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, Wayne was victorious. With the 1795 Treaty of Greenville, the Western Confederacy gave up their claims to Ohio.

A 1795 painting of the signing of the Treaty of Greenville. Source: Wikimedia Commons

4.6 Section Summary

Federalists and Democratic-Republicans interpreted the execution of the French monarch and the violent establishment of a French republic in very different ways. Revolutionaries’ excesses in France and the slaves’ revolt in the French colony of Haiti raised fears among Federalists of similar radicalism and slave uprisings on American shores. Democratic-Republicans took a more positive view of the French Revolution and grew suspicious of the Federalists. Domestically, the partisan divide came to a dramatic head in western Pennsylvania when distillers of whiskey, many aligned with the Democratic-Republicans, took action against the federal tax on their product. Washington led a massive force to put down the uprising, demonstrating Federalist intolerance of mob action. Though divided on many issues, the majority of white citizens agreed on the necessity of eradicating the Indian presence on the frontier.

4.7 Partisan Politics

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe how foreign relations affected American politics

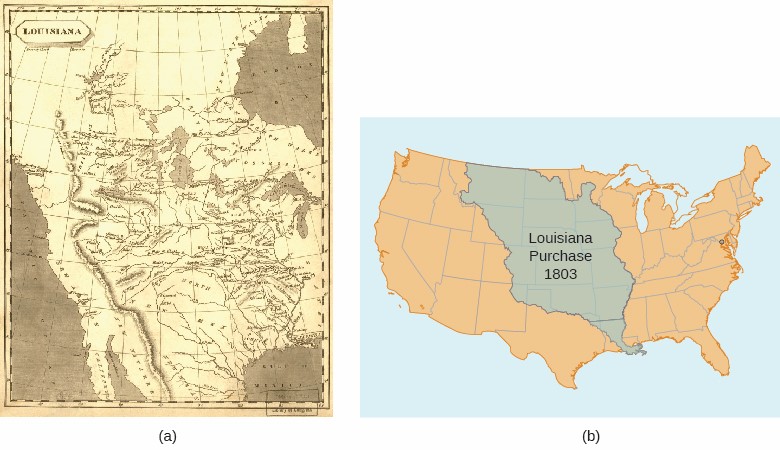

- Assess the importance of the Louisiana Purchase

George Washington, who was elected as President in 1768 and then reelected in 1792 by an overwhelming majority, refused to run for a third term, thus setting a precedent for future presidents. In the presidential election of 1796, the two parties—Federalist and Democratic-Republican—competed for the first time. Partisan rancor over the French Revolution and the Whiskey Rebellion fueled the divide between them, and Federalist John Adams defeated his Democratic-Republican rival Thomas Jefferson by a narrow margin of only three electoral votes. In 1800, another close election swung the other way, and Jefferson began a long period of Democratic-Republican government.

THE PRESIDENCY OF JOHN ADAMS

The war between Great Britain and France in the 1790s shaped U.S. foreign policy. As a new and, in comparison to the European powers, extremely weak nation, the American republic had no control over European events, and no real leverage to obtain its goals of trading freely in the Atlantic. To Federalist president John Adams, relations with France posed the biggest problem.

Because France and Great Britain were at war, the French Directory issued decrees stating that any ship carrying British goods could be seized on the high seas. In practice, this meant the French would target American ships, especially those in the West Indies, where the United States conducted a brisk trade with the British. France declared its 1778 treaty with the United States null and void, and as a result, France and the United States waged an undeclared war—or what historians refer to as the Quasi-War—from 1796 to 1800. Between 1797 and 1799, the French seized 834 American ships, and Adams urged the buildup of the U.S. Navy, which consisted of only a single vessel at the time of his election in 1796.

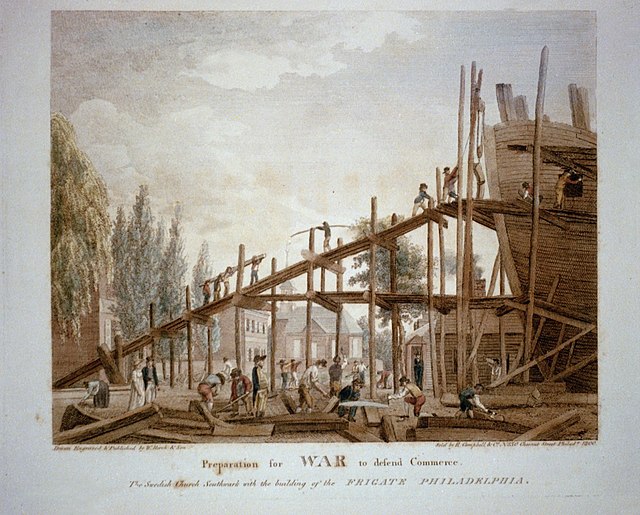

This 1799 print, entitled “Preparation for WAR to defend Commerce,” shows the construction of a naval ship, part of the effort to ensure the United States had access to free trade in the Atlantic world. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In 1797, Adams sought a diplomatic solution to the conflict with France and dispatched envoys to negotiate terms. The French foreign minister, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, sent emissaries who told the American envoys that the United States must repay all outstanding debts owed to France, lend France 32 million guilders (Dutch currency), and pay a £50,000 bribe before any negotiations could take place. News of the attempt to extract a bribe, known as the XYZ affair because the French emissaries were referred to as X, Y, and Z in letters that President Adams released to Congress, outraged the American public and turned public opinion decidedly against France. In the court of public opinion, Federalists appeared to have been correct in their interpretation of France, while the pro-French Democratic-Republicans had been misled.

The complicated situation in Haiti, which remained a French colony in the late 1790s, also came to the attention of President Adams. The president, with the support of Congress, had created a U.S. Navy that now included scores of vessels. Most of the American ships cruised the Caribbean, giving the United States the edge over France in the region. In Haiti, the rebellion leader Toussaint, who had to contend with various domestic rivals seeking to displace him, looked to end an U.S. embargo on France and its colonies, put in place in 1798, so that his forces would receive help to deal with the civil unrest. In early 1799, in order to capitalize upon trade in the lucrative West Indies and undermine France’s hold on the island, Congress ended the ban on trade with Haiti—a move that acknowledged Toussaint’s leadership, to the horror of American slaveholders. Toussaint was able to secure an independent black republic in Haiti by 1804.

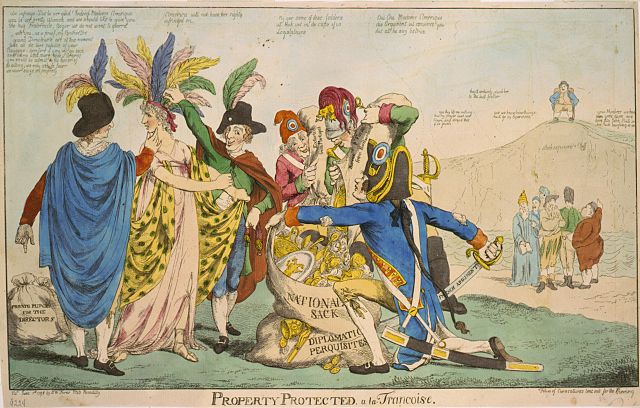

This anonymous 1798 cartoon, Property Protected à la Françoise, satirizes the XYZ affair. Five Frenchmen are shown plundering the treasures of a woman representing the United States. One man holds a sword labeled “French Argument” and a sack of gold and riches labeled “National Sack and Diplomatic Perquisites,” while the others collect her valuables. A group of other Europeans look on and commiserate that France treated them the same way. Source: Wikimedia Commons

THE ALIEN AND SEDITION ACTS