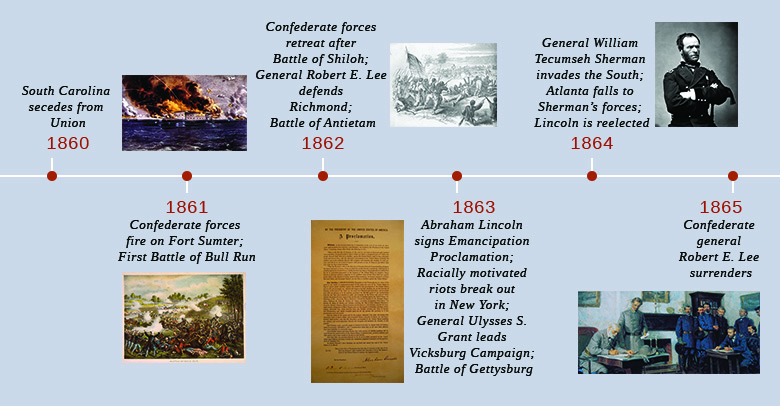

7 Chapter 7: The Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Settlement of the West, 1860–1880

The Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Settlement of the West, 1860–1880

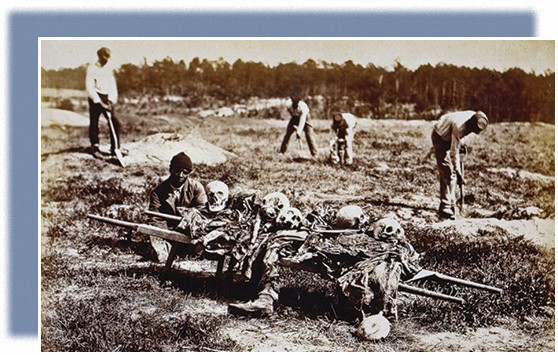

This photograph by John Reekie, entitled, “A burial party on the battle-field of Cold Harbor,” drives home the brutality and devastation wrought by the Civil War. Here, in April 1865, African Americans collect the bones of soldiers killed in Virginia during General Ulysses S. Grant’s Wilderness Campaign of May–June 1864. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Chapter Outline

Introduction, Watch and Learn, Questions to Guide Your Reading

7.1 The Origins and Outbreak of the Civil War

7.5 Congress and the Remaking of the South, 1865–1866

7.6 Radical Reconstruction, 1867–1872

7.7 The Collapse of Reconstruction

7.8 Homesteading: Dreams and Realities

7.9 The Impact of Expansion on Native peoples, Chinese immigrants, and Hispanic citizens

Summary Timelines, Chapter 7 Self-Test, Chapter 7 Key Term Crossword Puzzle

Introduction

Few times in U.S. history have been as turbulent and transformative as the Civil War and the twelve years that followed. Between 1865 and 1877, one president was murdered and another impeached. The Constitution underwent major revision with the addition of three amendments. The effort to impose Union control and create equality in the defeated South ignited a fierce backlash as various terrorist and vigilante organizations, most notably the Ku Klux Klan, battled to maintain a pre–Civil War society in which whites held complete power. These groups unleashed a wave of violence, including lynching and arson, aimed at freed blacks and their white supporters. Historians refer to this era as Reconstruction, when an effort to remake the South faltered and ultimately failed.

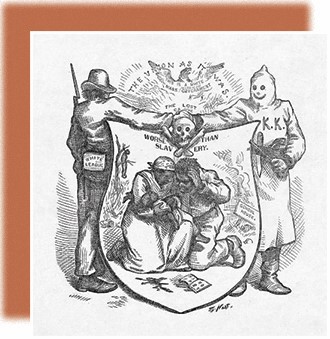

The following political cartoon expresses the anguish many Americans felt in the decade after the Civil War. The South, which had experienced catastrophic losses during the conflict, was reduced to political dependence and economic destitution. This humiliating condition led many southern whites to vigorously contest Union efforts to transform the South’s racial, economic, and social landscape. Supporters of equality grew increasingly dismayed at Reconstruction’s failure to undo the old system, which further compounded the staggering regional and racial inequalities in the United States.

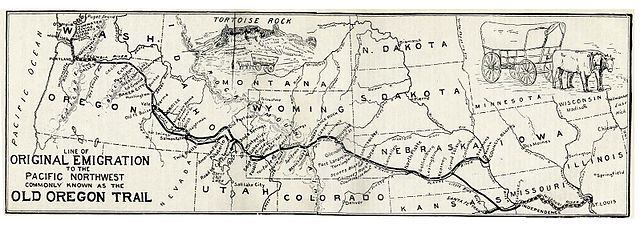

For a variety of reasons, in the decades following the Civil War, Americans increasingly felt compelled to fulfill their “Manifest Destiny,” a phrase that came to mean that they were expected to spread across the land given to them by God and, most importantly, spread predominantly American values to the frontier. Hundreds, and then hundreds of thousands, of settlers packed their lives into wagons and set out, following the Oregon, California, and Santa Fe Trails, to seek a new life in the West. Some sought open lands and greater freedom to fulfill the democratic vision originally promoted by Thomas Jefferson and experienced by their ancestors. Others saw economic opportunity. Still others believed it was their job to spread the word of God to the “heathens” on the frontier. Whatever their motivation, the great migration was underway.

In this political cartoon by Thomas Nast, which appeared in Harper’s Weekly in October 1874, the “White League” shakes hands with the Ku Klux Klan over a shield that shows a couple weeping over a baby. In the background, a schoolhouse burns, and a lynched freedman is shown hanging from a tree. Above the shield, which is labeled “Worse than Slavery,” the text reads, “The Union as It Was: This Is a White Man’s Government.” Source: Wikimedia Commons

Watch and Learn (Crash Course History videos for chapter 7)

- The 1860 Election & the Road to Disunion

- The Civil War, Part 1

- The Civil War, Part 2

- Black Americans in the Civil War

- Reconstruction

- Westward Expansion

Questions to Guide Your Reading:

- Why did the North prevail in the Civil War? What might have turned the tide of the war against the North?

- What do you believe to be the enduring qualities of the Gettysburg Address? Why has this two-minute speech so endured?

- What role did women and African Americans play in the war?

- How do you think would history have been different if Lincoln had not been assassinated? How might his leadership after the war have differed from that of Andrew Johnson?

- Consider the differences between the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments. What does the Fourteenth Amendment do that the Thirteenth does not?

- Consider social, political, and economic equality. In what ways did Radical Reconstruction address and secure these forms of equality? Where did it fall short?

- Consider the problem of terrorism during Radical Reconstruction. If you had been an adviser to President Grant, how would you propose to deal with the problem?

- Describe the philosophy of Manifest Destiny. What effect did it have on Americans’ westward migration? How might the different groups that migrated have sought to apply this philosophy to their individual circumstances?

- Describe the ways in which the U.S. government, local governments, and/or individuals attempted to interfere with the specific cultural traditions and customs of Indians, Hispanics, and Chinese immigrants. What did these efforts have in common? How did each group respond?

7.1 The Origins and Outbreak of the Civil War

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the major events that occurred during the Secession Crisis

- Describe the creation and founding principles of the Confederate States of America

The 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln was a turning point for the United States. Throughout the tumultuous 1850s, the Fire-Eaters of the southern states had been threatening to leave the Union. With Lincoln’s election, they prepared to make good on their threats. The perceived threat posed by the Republican victory in the election of 1860 spurred eleven southern states to leave the Union to form the Confederate States of America, a new republic dedicated to maintaining and expanding slavery. The Union, led by President Lincoln, was unwilling to accept the departure of these states and committed itself to restoring the country. Beginning in 1861 and continuing until 1865, the United States engaged in a brutal Civil War that claimed the lives of over 600,000 soldiers. By 1863, the conflict had become not only a war to save the Union, but also a war to end slavery in the United States. Only after four years of fighting did the North prevail. The Union was preserved, and the institution of slavery had been destroyed in the nation.

THE CAUSES OF THE CIVIL WAR

Lincoln’s election sparked the southern secession fever into flame, but it did not cause the Civil War. For decades before Lincoln took office, the sectional divisions in the country had been widening. Both the Northern and southern states engaged in inflammatory rhetoric and agitation, and violent emotions ran strong on both sides.

The question of slavery’s expansion westward proved to be especially contentious. The debate over whether new states would be slave or free reached back to the controversy over statehood for Missouri beginning in 1819 and Texas in the 1830s and early 1840s. This question arose again after the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), when the government debated whether slavery would be permitted in the territories taken from Mexico. Efforts in Congress to reach a compromise in 1850 fell back on the principle of popular sovereignty-letting the people in the new territories south of the 1820 Missouri Compromise line decide whether to allow slavery. This same principle came to be applied to the Kansas-Nebraska territories in 1854, a move that added fuel to the fire of sectional conflict by destroying the Missouri Compromise boundary and leading to the birth of the Republican Party. In the end, popular sovereignty proved to be no solution at all. This was especially true in “Bleeding Kansas” in the mid-1850s, as pro- and antislavery forces battled each other in an effort to gain the upper hand.

The formation of the Liberty Party (1840), the Free-Soil Party (1848), and the Republican Party (1854), all of which strongly opposed the spread of slavery to the West, brought the question solidly into the political arena. Although not all those who opposed the westward expansion of slavery had a strong abolitionist bent, the attempt to limit slaveholders’ control of their human property stiffened the resolve of southern leaders to defend their society at all costs. Prohibiting slavery’s expansion, they argued, ran counter to fundamental American property rights. Across the country, people of all political stripes worried that the nation’s arguments would cause irreparable rifts in the country.

THE CREATION OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES OF AMERICA

These fears became real when South Carolina seceded from the United States on December 20, 1860. Three more states of the Deep South-Mississippi, Florida, and Alabama-seceded shortly thereafter. Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas joined them in rapid succession. These seven states quickly formed a new government called the Confederate States of America (CSA), or the Confederacy. The Confederate Constitution declared that the new nation existed to defend and perpetuate racial slavery, and the leadership of the slaveholding class. Specifically, the constitution protected the interstate slave trade, guaranteed that slavery would exist in any new territory gained by the Confederacy, and, perhaps most importantly, in Article One, Section Nine, declared that “No … law impairing or denying the right of property in negro slaves shall be passed.” Jefferson Davis of Mississippi was chosen to be President of the new nation and Alexander Stephens of Georgia as vice president.

Not all residents of the border states and the Upper South wished to join the Confederacy, however. Pro-Union feelings remained strong in Tennessee, especially in the eastern part of the state where slaves were few and consisted largely of house servants owned by the wealthy. While most slaveholding states joined the Confederacy, four crucial slave states remained in the Union. Delaware, which was technically a slave state despite its tiny, enslaved population, never voted to secede. Maryland, despite deep divisions, remained in the Union as well. Missouri became the site of vicious fighting and the home of pro-Confederate guerillas but never joined the Confederacy. Kentucky declared itself neutral, although that did little to stop the fighting that occurred within the state. In all, these four states deprived the Confederacy of key resources and soldiers.

This map illustrates the southern states that seceded from the Union and formed the Confederacy in 1861, at the outset of the Civil War. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The state of Virginia literally was split on the issue of secession. Residents in the north and west of the state, where few enslavers resided, rejected secession. These counties subsequently united to form “West Virginia,” which entered the Union as a free state in 1863. The rest of Virginia, including the historic lands along the Chesapeake Bay joined the Confederacy. The addition of this area gave the Confederacy even greater hope and brought General Robert E. Lee, arguably the best military commander of the day, to their side.

FORT SUMTER

In his inaugural address, Lincoln had declared that the Union could not be dissolved by individual state actions, and, therefore, secession was unconstitutional. He also made it clear to Southern secessionists that he would fight to maintain federal property and to keep the Union intact.

Lincoln’s commitment to defending federal territory was tested in April of 1861 when the army of the newly formed Confederate States of America attacked Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. On April 12, 1861, Confederate forces in Charleston began a bombardment of Fort Sumter. Two days later, the Union soldiers there surrendered. The loss of Fort Sumter proved to be the flashpoint in the contest between the new Confederacy and the federal government. The attack on Fort Sumter meant war had come, and on April 15, 1861, Lincoln called upon loyal states to supply armed forces to defeat the rebellion and regain Fort Sumter.

The Confederacy’s attack on Fort Sumter, depicted here in an 1861 lithograph by Currier and Ives, stoked pro-war sentiment on both sides of the conflict. Source: Wikimedia Commons

7.1 Section Summary

The election of Abraham Lincoln to the presidency in 1860 proved to be a watershed event. While it did not cause the Civil War, it was the culmination of increasing tensions between the proslavery South and the antislavery North. Before Lincoln had even taken office, seven Deep South states had seceded from the Union to form the Confederate States of America, dedicated to maintaining racial slavery and white supremacy. The time for compromise had come to an end. With the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, the Civil War began.

7.2 The Carnage of War

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Assess the strengths and weaknesses of the Confederacy and the Union

- Understand the impact of the Civil War on the United States

In 1861, enthusiasm for war ran high on both sides. The North fought to restore the Union, which Lincoln declared could never be broken. The Confederacy, which by the summer of 1861 consisted of eleven states, fought for its independence from the United States. The continuation of slavery was a central issue in the war, of course, although abolitionism and western expansion also played roles, and Northerners and Southerners alike flocked eagerly to the conflict. Both sides thought it would be over quickly. Militarily, however, the North and South were more equally matched than Lincoln had realized, and it soon became clear that the war effort would be neither brief nor painless. In 1861, Americans in both the North and South romanticized war as noble and positive. Soon the carnage and slaughter would awaken them to the horrors of war.

THE FIRST BATTLE OF BULL RUN

After the fall of Fort Sumter on April 15, 1861, Lincoln called for seventy-five thousand volunteers from state militias to join federal forces. His goal was a ninety-day campaign to put down the Southern rebellion. The response from state militias was overwhelming, and the number of Northern troops exceeded the requisition. Also in April, Lincoln put in place a naval blockade of the South, a move that gave tacit recognition of the Confederacy while providing a legal excuse for the British and the French to trade with Southerners. The Confederacy responded to the blockade by declaring that a state of war existed with the United States. This official pronouncement confirmed the beginning of the Civil War.

Many believed that a single, heroic battle would decide the contest. Some questioned how committed Southerners really were to their cause. Northerners hoped that most Southerners would not actually fire on the American flag. Meanwhile, Lincoln and military leaders in the North hoped a quick blow to the South, especially if they could capture the Confederacy’s new capital of Richmond, Virginia, would end the rebellion before it went any further. On July 21, 1861, the two armies met near Manassas, Virginia, along Bull Run Creek, only thirty miles from Washington, DC. So great was the belief that this would be a climactic Union victory that many Washington socialites and politicians brought picnic lunches to a nearby area, hoping to witness history unfolding before them. At the First Battle of Bull Run, also known as First Manassas, some sixty thousand troops assembled, most of whom had never seen combat, and each side sent eighteen thousand into the fray. The Union forces attacked first, only to be pushed back. The Confederate forces then carried the day, sending the Union soldiers and Washington, DC, onlookers scrambling back from Virginia and destroying Union hopes of a quick, decisive victory. Instead, the war would drag on for four long, deadly years

BALANCE SHEET: THE UNION AND THE CONFEDERACY

As it became clearer that the Union would not be dealing with an easily quashed rebellion, the two sides assessed their strengths and weaknesses. At the onset on the war, in 1861 and 1862, they stood as relatively equal combatants. At the onset on the war, in 1861 and 1862, both sides engaged in the War stood as relatively equal combatants.

The Confederates had the advantage of being able to wage a defensive war, rather than an offensive one. They had to protect and preserve their new boundaries, but they did not have to be the aggressors against the Union. The war would be fought primarily in the South, which gave the Confederates the advantages of the knowledge of the terrain and the support of the civilian population. Further, the vast coastline from Texas to Virginia offered ample opportunities to evade a Union Naval blockade. And with the addition of the Upper South states, especially Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas, the Confederacy gained a much larger share of natural resources and industrial might than the Deep South states could muster.

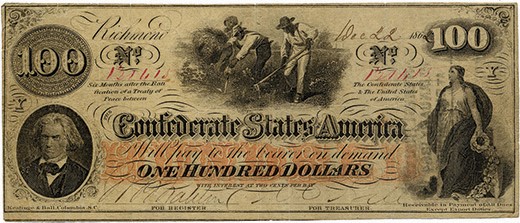

Still, the Confederacy had disadvantages. The South lacked substantive industry or an extensive railroad infrastructure to move men and supplies. To deal with the lack of commerce and the resulting lack of funds, the Confederate government began printing paper money, leading to runaway inflation. Finally, the population of the South stood at fewer than nine million people, of whom nearly four million were enslaved blacks, compared to over twenty million residents in the North. These limited numbers became a major factor as the war dragged on and the death toll rose.

The Confederacy started printing paper money at an accelerated rate, causing runaway inflation and an economy in which formerly well-off people were unable to purchase food. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Dissent within the Confederacy affected the South’s ability to fight the war. Confederate politicians disagreed over the amount of power that the central government should be allowed to exercise. Class divisions also divided Confederates. Poor whites resented the ability of wealthy slaveholders to excuse themselves from military service. Racial tensions plagued the South as well. On those occasions when free blacks volunteered to serve in the Confederate army, they were turned away, and enslaved African Americans were regarded with fear and suspicion, as whites whispered among themselves about the possibility of slave insurrections.

The Union side held many advantages as well. Its larger population, bolstered by continued immigration from Europe throughout the 1860s, gave it greater manpower reserves to draw upon. The North’s greater industrial capabilities and extensive railroad grid made it far better able to mobilize men and supplies for the war effort. The Industrial Revolution and the transportation revolution, beginning in the 1820s and continuing over the next several decades, had transformed the North. Throughout the war, the North was able to produce more war materials and move goods more quickly than the South. Furthermore, the farms of New England, the Mid-Atlantic, the Old Northwest, and the prairie states supplied Northern civilians and Union troops with abundant food throughout the war. Food shortages and hungry civilians were common in the South, where the best land was devoted to raising cotton, but not in the North.

Unlike the South, however, which could hunker down to defend itself and needed to maintain relatively short supply lines, the North had to go forth and conquer. Union armies had to establish long supply lines, and Union soldiers had to fight on unfamiliar ground and contend with a hostile civilian population off the battlefield. In short, although it had better resources and a larger population, the Union faced a daunting task against the well-positioned Confederacy.

Mobilizing Troops

When the initial emotional outburst of enthusiasm for war in the Confederacy waned, the Confederate government instituted a military draft in April 1862. Under the terms of the draft, all men between the ages of eighteen and thirty-five were required to serve three years. The draft had a different effect on men of different socioeconomic classes. An important loophole permitted men to hire substitutes instead of serving in the Confederate army. This provision favored the wealthy over the poor, and led to much resentment and resistance.

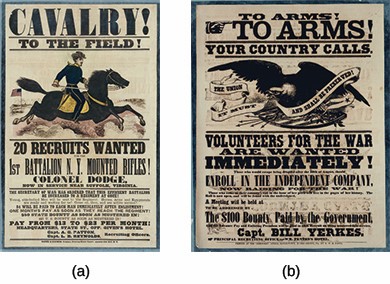

The Union tried to provide additional incentives for soldiers, in the form of bounties, to enlist without waiting for the draft, as shown in recruitment posters (a) and (b). Source: Wikimedia Commons

Like the Confederacy, the Union turned to conscription to provide the troops needed for the war. In March 1863, Congress passed the Enrollment Act, requiring all unmarried men between the ages of twenty and twenty-five, and all married men between the ages of thirty-five and forty-five—including immigrants who had filed for citizenship—to register with the Union to fight in the Civil War. All who registered were subject to military service, and draftees were selected by a lottery system. As in the South, a loophole in the law allowed individuals to hire substitutes if they could afford it. Others could avoid enlistment by paying $300 to the federal government. In keeping with the Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, African Americans were not citizens and were therefore exempt from the draft.

Both the Confederate and Union governments suspended habeas corpus rights, so those suspected of sympathies for the other side could be arrested and held without being given the reason. In both the North and the South, the Civil War dramatically increased the power of the belligerent governments. Breaking all past precedents in American history, both the Confederacy and the Union employed the power of their central governments to mobilize resources and citizens.

Women’s Mobilization

As men on both sides mobilized for the war, so did women. In both the North and the South, women were forced to take over farms and businesses abandoned by their husbands as they left for war. Women organized themselves into ladies’ aid societies to sew uniforms, knit socks, and raise money to purchase necessities for the troops. In the South, women took wounded soldiers into their homes to nurse. In the North, women volunteered for the United States Sanitary Commission, which formed in June 1861. They inspected military camps with the goal of improving cleanliness and reducing the number of soldiers who died from disease, the most common cause of death in the war. They also raised money to buy medical supplies and helped with the injured. Other women found jobs in the Union army as cooks and laundresses. Thousands volunteered to care for the sick and wounded in response to a call by reformer Dorothea Dix, who was placed in charge of the Union army’s nurses. Women on both sides also acted as spies and, disguised as men, engaged in combat.

EMANCIPATION

Early in the war, President Lincoln approached the issue of slavery cautiously. While he disapproved of slavery personally, he did not believe that he had the authority to abolish it. Furthermore, he feared that making the abolition of slavery an objective of the war would cause the border slave states to join the Confederacy. His one objective in 1861 and 1862 was to restore the Union. Lincoln thus moved slowly and cautiously on the issue of abolition.

However, as Republicans in Congress continued to call for the end of slavery. Responding to these demands, Lincoln presented an ultimatum to the Confederates on September 22, 1862. He gave them until January 1, 1863, to rejoin the Union. If they did, slavery would continue in the slave states. If they refused to rejoin, however, the war would continue and all slaves would be freed at its conclusion. When the Confederacy took no action, on January 1, 1863, Lincoln made good on his threat and signed the Emancipation Proclamation. It stated “That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

The proclamation did not immediately free the slaves in the Confederate states. Although they were in rebellion against the United States, the lack of the Union army’s presence in such areas meant that the president’s directive could not be enforced. The proclamation also did not free slaves in the border states that had remained loyal to the Union, because these states were not, by definition, in rebellion. Despite the limits of the proclamation, Lincoln dramatically shifted the objective of the war increasingly toward ending slavery. The Emancipation Proclamation became a monumental step forward on the road to changing the character of the United States.

The proclamation generated quick and dramatic reactions. The news created euphoria among slaves, as it signaled the eventual end of their bondage. Predictably, Confederate leaders raged against the proclamation, reinforcing their commitment to fight to maintain slavery, the foundation of the Confederacy. In the North, opinions split widely on the issue. Abolitionists praised Lincoln’s actions, which they saw as the fulfillment of their long campaign to strike down an immoral institution. But other Northerners, especially Irish, working-class, urban dwellers loyal to the Democratic Party and others with racist beliefs, hated the new goal of emancipation and found the idea of freed slaves repugnant. At its core, much of this racism had an economic foundation: Many Northerners feared competing with emancipated slaves for scarce jobs.

|

|

DEFINING “AMERICAN” |

|

Lincoln’s Evolving Thoughts on Slavery President Lincoln wrote the following letter to newspaper editor Horace Greeley on August 22, 1862. In it, Lincoln states his position on slavery, which is notable for being a middle-of-the-road stance. Lincoln’s later public speeches on the issue take the more strident antislavery tone for which he is remembered. “I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored the nearer the Union will be “the Union as it was.” If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time save Slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy Slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or destroy Slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that. What I do about Slavery and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save this Union, and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union. I shall do less whenever I shall believe what I am doing hurts the cause, and I shall do more whenever I shall believe doing more will help the cause. I shall try to correct errors when shown to be errors; and I shall adopt new views so fast as they shall appear to be true views. I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty, and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men, everywhere, could be free. Yours, A. LINCOLN.” |

|

UNION ADVANCES

The war in the west turned in the North’s favor in 1863. At the start of the year, Union forces controlled much of the Mississippi River, including the ports of New Orleans and Memphis. General Ulysses S. Grant, was successful in capturing Vicksburg in July 1863, thus effectively splitting the Confederacy. This victory inflicted a serious blow to the Southern war effort.

Beginning in June 1863, General Lee moved the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia north through Maryland. The Union army—the Army of the Potomac—traveled east to end up alongside the Confederate forces. The two armies met at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The resulting battle lasted three days, July 1–3, and remains the biggest and costliest battle ever fought in North America. Both sides suffered staggering losses. Total casualties numbered around twenty-three thousand for the Union and some twenty-eight thousand among the Confederates. With its defeats at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, both on the same day, the Confederacy lost its momentum. The tide had turned in favor of the Union in both the east and the west.

When the decision was made to create a cemetery honoring the Union dead, President Lincoln was invited to attend the dedication ceremony. Lincoln addressed the crowd for several minutes. In his speech, known as the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln invoked the Founding Fathers and the spirit of the American Revolution. The Union soldiers who had died at Gettysburg, he proclaimed, had died not only to preserve the Union, but also to guarantee freedom and equality for all.

|

|

DEFINING “AMERICAN” |

|

Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address Several months after the battle at Gettysburg, Lincoln traveled to Pennsylvania and, speaking to an audience at the dedication of the new Soldiers’ National Ceremony near the site of the battle, he delivered his now-famous Gettysburg Address to commemorate the turning point of the war and the soldiers whose sacrifices had made it possible. The two-minute speech was politely received at the time, although press reactions split along party lines. Upon receiving a letter of congratulations from Massachusetts politician and orator William Everett, whose speech at the ceremony had lasted for two hours, Lincoln said he was glad to know that his brief address, now virtually immortal, was not “a total failure.” “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. “Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. “It is for us the living . . . to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” —Abraham Lincoln, Gettysburg Address, November 19, 1863 |

|

7.2 Section Summary

Many in both the North and the South believed that a short, decisive confrontation in 1861 would settle the question of the Confederacy. These expectations did not match reality, however, and the war dragged on into a second year. Both sides mobilized, with advantages and disadvantages on each side that led to a rough equilibrium. The year 1863 proved decisive in the Civil War for two major reasons. First, the Union transformed the purpose of the struggle from restoring the Union to ending slavery. While Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation actually succeeded in freeing few enslaved people, it made freedom for African Americans a cause of the Union. Second, the tide increasingly turned against the Confederacy. The success of the Vicksburg Campaign had given the Union control of the Mississippi River, and Lee’s defeat at Gettysburg had ended the attempted Confederate invasion of the North.

7.3 The Union Triumphant

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain key reasons for the Union victory over the Confederacy

- Explain the concept “total war” and evaluate whether the Civil War is an example of one

By the outset of 1864, after three years of war, the Union had mobilized its resources for the ongoing struggle on a massive scale. The government had overseen the construction of new railroad lines and for the first time used standardized rail tracks that allowed the North to move men and materials with greater ease. The North’s economy had shifted to a wartime model. The Confederacy however experienced ever-greater hardships after years of war. Without the population of the North, it faced a shortage of manpower. The lack of industry, compared to the North, undercut the ability to sustain and wage war. Rampant inflation as well as food shortages in the South lowered morale.

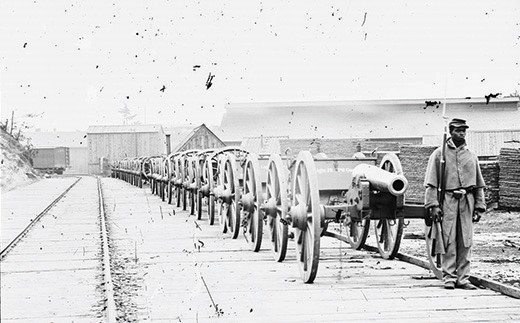

This 1865 daguerreotype illustrates three of the Union’s distinct advantages: African American soldiers, a stream of cannons and supplies, and an extensive railroad grid. Source: Wikimedia Commons

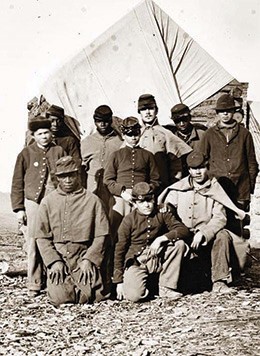

AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIERS

At the beginning of the war, in 1861 and 1862, Union forces had used contrabands, or escaped slaves, for manual labor. The Emancipation Proclamation, however, led to the enrollment of African American men as Union soldiers. Huge numbers, former enslaved black Americans, as well as free blacks from the North, enlisted, and by the end of the war in 1865, their numbers had swelled to over 190,000. Racism among whites in the Union army ran deep, however, fueling the belief that black soldiers could never be effective or trustworthy. Although black soldiers saw combat duty, many black regiments were limited to hauling supplies, serving as cooks, digging trenches, and doing other types of labor, rather than serving on the battlefield.

African American soldiers also received lower wages than their white counterparts: ten dollars per month, with three dollars deducted for clothing. White soldiers, in contrast, received thirteen dollars monthly, with no deductions. Abolitionists and their Republican supporters in Congress worked to correct this discriminatory practice, and in 1864, black soldiers began to receive the same pay as white soldiers plus retroactive pay to 1863.

For their part, African American soldiers welcomed the opportunity to prove themselves. Some 85 percent were former enslaved people who were fighting for the liberation of all those who were enslaved and the end of slavery. When given the opportunity to serve, many black regiments did so heroically. One such regiment, the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers, distinguished itself at Fort Wagner in South Carolina by fighting valiantly against an entrenched Confederate position. They willingly gave their lives for the cause.

African American and white soldiers of the Union army pose together in this photograph, although in reality, black soldiers were often kept separate and given only menial jobs. Source: Wikimedia Commons

THE CAMPAIGNS OF 1864 AND 1865

In the final years of the war, the Union continued its efforts on both the eastern and western fronts while bringing the war into the Deep South. Union forces increasingly engaged in total war, not distinguishing between military and civilian targets. They destroyed everything that lay in their path, committed to breaking the will of the Confederacy and forcing an end to the war.

General Sherman invaded the Deep South, advancing slowly from Tennessee into Georgia, confronted at every turn by the Confederates. Atlanta fell to Union forces on September 2, 1864. In keeping with the logic of total war, Sherman’s forces cut a swath of destruction to Savannah. On Sherman’s March to the Sea, the Union army, seeking to demoralize the South, destroyed everything in its path, despite strict instructions regarding the preservation of civilian property. Although towns were left standing, houses and barns were burned. Homes were looted, food was stolen, crops were destroyed, orchards were burned, and livestock was killed or confiscated. Savannah fell on December 21, 1864. In 1865, Sherman’s forces invaded South Carolina, capturing Charleston and Columbia. In Columbia, the state capital, the Union army burned enslavers’ homes and destroyed much of the city. From South Carolina, Sherman’s force moved north in an effort to join Grant and destroy Lee’s army.

|

|

MY STORY |

|

Dolly Sumner Lunt on Sherman’s March to the Sea The following account is by Dolly Sumner Lunt, a widow who ran her Georgia cotton plantation after the death of her husband. She describes General Sherman’s march to Savannah, where he enacted the policy of total war by burning and plundering the landscape to inhibit the Confederates’ ability to keep fighting. “Alas! little did I think while trying to save my house from plunder and fire that they were forcing my boys [slaves] from home at the point of the bayonet. One, Newton, jumped into bed in his cabin, and declared himself sick. Another crawled under the floor,—a lame boy he was,—but they pulled him out, placed him on a horse, and drove him off. Mid, poor Mid! The last I saw of him, a man had him going around the garden, looking, as I thought, for my sheep, as he was my shepherd. Jack came crying to me, the big tears coursing down his cheeks, saying they were making him go. I said: ‘Stay in my room.’ “But a man followed in, cursing him and threatening to shoot him if he did not go; so poor Jack had to yield. . . . Sherman himself and a greater portion of his army passed my house that day. All day, as the sad moments rolled on, were they passing not only in front of my house, but from behind; they tore down my garden palings, made a road through my back-yard and lot field, driving their stock and riding through, tearing down my fences and desolating my home—wantonly doing it when there was no necessity for it. . . . About ten o’clock they had all passed save one, who came in and wanted coffee made, which was done, and he, too, went on. A few minutes elapsed, and two couriers riding rapidly passed back. Then, presently, more soldiers came by, and this ended the passing of Sherman’s army by my place, leaving me poorer by thirty thousand dollars than I was yesterday morning. And a much stronger Rebel!” |

|

THE WAR ENDS

By the spring of 1865, it had become clear to both sides that the Confederacy could not last much longer. Most of its major cities, ports, and industrial centers—Atlanta, Savannah, Charleston, Columbia, Mobile, New Orleans, and Memphis—had been captured. In April 1865, Lee had abandoned both Petersburg and Richmond. His goal in doing so was to unite his depleted army with Confederate forces commanded by General Johnston. Grant effectively cut him off. On April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. By that time, he had fewer than 35,000 soldiers, while Grant had some 100,000. Meanwhile, Sherman’s army proceeded to North Carolina, where General Johnston surrendered on April 19, 1865. The Civil War had come to an end. The war had cost the lives of more than 600,000 soldiers. Many more had been wounded. Thousands of women were left widowed. Children were left without fathers, and many parents were deprived of a source of support in their old age. In some areas, where local volunteer units had marched off to battle, never to return, an entire generation of young women was left without marriage partners. Millions of dollars’ worth of property had been destroyed, and towns and cities were laid to waste. With the conflict finally over, the very difficult work of reconciling North and South and reestablishing the United States lay ahead.

Vastly outnumbered by the Union army, the Confederate general Robert E. Lee (seated at the left) surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse. Source: Wikimedia Commons

7.3 Section Summary

The Confederacy faced a long war with limited resources and no allies. Lincoln won reelection in 1864, and continued to pursue the Union campaign, not only in the east and west, but also with a drive into the South under the leadership of General Sherman, whose March to the Sea through Georgia destroyed everything in its path. Cut off and outnumbered, Confederate general Lee surrendered to Union general Grant on April 9 at Appomattox Court House in Virginia. Within days of Lee’s surrender, Confederate troops had lay down their arms, and the devastating war came to a close.

7.4 Restoring the Union

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe Lincoln’s plan to restore the Union at the end of the Civil War

- Discuss the tenets of Radical Republicanism

- Analyze the success or failure of the Thirteenth Amendment

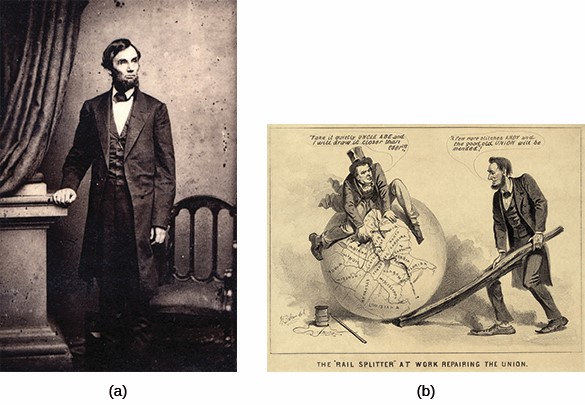

The end of the Civil War saw the beginning of the Reconstruction era, when former rebel Southern states were integrated back into the Union. President Lincoln moved quickly to achieve the war’s ultimate goal: reunification of the country. He proposed a generous and non-punitive plan to return the former Confederate states speedily to the United States. President Lincoln oversaw the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery, but he did not live to see its ratification.

Thomas Le Mere took this albumen silver print (a) of Abraham Lincoln in April 1863. Le Mere thought a standing pose of Lincoln would be popular. In this political cartoon from 1865 (b), Lincoln and his vice president, Andrew Johnson, endeavor to sew together the torn pieces of the Union. Source: Wikimedia Commons

From the outset of the rebellion in 1861, Lincoln’s overriding goal had been to bring the Southern states quickly back into the fold in order to restore the Union. In early December 1863, the president began the process of reunification by unveiling a three-part proposal known as the ten percent plan that outlined how the states would return. The ten percent plan gave a general pardon to all Southerners except high-ranking Confederate government and military leaders; required 10 percent of the 1860 voting population in the former rebel states to take a binding oath of future allegiance to the United States and the emancipation of enslaved people; and declared that once those voters took those oaths, the restored Confederate states would draft new state constitutions.

THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT

Despite the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, the legal status of enslaved people and the institution of slavery remained unresolved. To deal with the remaining uncertainties, the Republican Party had made the abolition of slavery a top priority by including the issue in its 1864 party platform. The platform left no doubt about the intention to abolish slavery. The president, along with his fellow Republicans, made good on this campaign promise in 1864 and 1865. A proposed constitutional amendment passed the Senate in April 1864, and the House of Representatives concurred in January 1865. The amendment then made its way to the states, where it swiftly gained the necessary support, including in the South. In December 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment was officially ratified and added to the Constitution. The first amendment added to the Constitution since 1804, it overturned a centuries-old practice by permanently abolishing slavery.

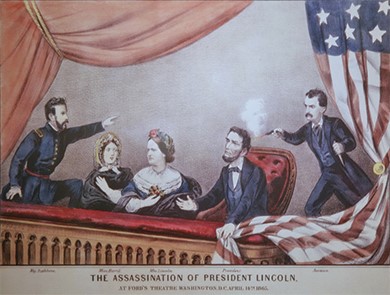

President Lincoln never saw the final ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment. On April 14, 1865, the Confederate supporter and well-known actor John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln while he was attending a play, Our American Cousin, at Ford’s Theater in Washington. The president died the next day. Lincoln’s death earned him immediate martyrdom, and hysteria spread throughout the North. To many Northerners, the assassination suggested an even greater conspiracy than what was revealed, masterminded by the unrepentant leaders of the defeated Confederacy. Militant Republicans would use and exploit this fear relentlessly in the ensuing months.

In The Assassination of President Lincoln (1865), by Currier and Ives, John Wilkes Booth shoots Lincoln in the back of the head as he sits in the theater box with his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, and their guests, Major Henry R. Rathbone and Clara Harris. Source: Wikimedia Commons

ANDREW JOHNSON AND THE BATTLE OVER RECONSTRUCTION

Lincoln’s assassination elevated Vice President Andrew Johnson, a Democrat, to the presidency. Unexpectedly elevated to the presidency in 1865, this formerly impoverished tailor’s apprentice and unwavering antagonist of the wealthy southern planter class now found himself tasked with administering the restoration of a destroyed South. Lincoln’s position as president had been that the secession of the Southern states was never legal; that is, they had not succeeded in leaving the Union, therefore they still had certain rights to self-government as states. In keeping with Lincoln’s plan, Johnson desired to quickly reincorporate the South back into the Union on lenient terms and heal the wounds of the nation. In fact, President Johnson’s Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction in May 1865 provided sweeping “amnesty and pardon” to rebellious Southerners. It returned their property to them, with the notable exception of their former enslaved people, and it asked only that they affirm their support for the Constitution of the United States. Despite the outcries of Republicans in Congress, by early 1866 Johnson announced that all former Confederate states had satisfied the necessary requirements. According to him, nothing more needed to be done; the Union had been restored.

This position angered many in his own party. Radical Republicans in Congress, and their northern constituents, greatly resented Johnson’s lenient treatment of the former Confederate state. They refused to acknowledge the southern state governments he allowed. As a result, they would not permit senators and representatives from the former Confederate states to take their places in Congress. Instead, the Radical Republicans created a joint committee of representatives and senators to oversee Reconstruction. In the 1866 congressional elections, they gained control of the House, and in the ensuing years they pushed for the dismantling of the old southern order and the complete reconstruction of the South. The northern Radical Republican plan for Reconstruction looked to overturn southern society and specifically aimed at ending the plantation system. This effort put them squarely at odds with President Johnson, who remained unwilling to compromise with Congress.

7.4 Section Summary

President Lincoln worked to reach his goal of reunifying the nation quickly and proposed a lenient plan to reintegrate the Confederate states. After his murder in 1865, Lincoln’s vice president, Andrew Johnson, sought to reconstitute the Union quickly, pardoning Southerners en-masse and providing Southern states with a clear path back to readmission. By 1866, Johnson announced the end of Reconstruction. Radical Republicans in Congress disagreed, however, and in the years ahead would put forth their own plan of Reconstruction.

7.5 Congress and the Remaking of the South, 1865–1866

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the efforts made by Congress in 1865 and 1866 to bring to life its vision of Reconstruction

- Explain how the Fourteenth Amendment transformed the Constitution

President Johnson and Congress’s views on Reconstruction grew even further apart as Johnson’s presidency progressed. Congress repeatedly pushed for greater rights for freed people and a far more thorough reconstruction of the South, while Johnson pushed for leniency and a swifter reintegration. President Johnson lacked Lincoln’s political skills and instead exhibited a stubbornness and confrontational approach that aggravated an already difficult situation.

THE FREEDMEN’S BUREAU

Freed people everywhere celebrated the end of slavery and immediately began to take steps to improve their own condition by seeking what had long been denied to them: land, financial security, education, and the ability to participate in the political process. They wanted to be reunited with family members, grasp the opportunity to make their own independent living, and exercise their right to have a say in their own government. However, they faced the wrath of defeated but un-reconciled southerners who were determined to keep blacks an impoverished and despised underclass. Recognizing the widespread devastation in the South and the dire situation of freed people, Congress created the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands in March 1865, popularly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau.

|

|

AMERICANA |

|

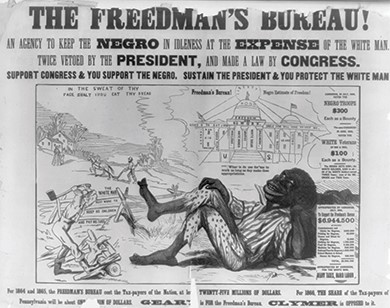

The Freedmen’s Bureau This image shows a campaign poster for Hiester Clymer, who ran for governor of Pennsylvania in 1866 on a platform of white supremacy. The caption of this image reads, “The Freedman’s Bureau! An agency to keep the Negro in idleness at the expense of the white man. Twice vetoed by the President, and made a law by Congress. Support Congress & you support the Negro. Sustain the President & you protect the white man.” The image in the foreground shows an indolent black man wondering, “Whar is de use for me to work as long as dey make dese appropriations.” White men toil in the background, chopping wood and plowing a field. The text above them reads, “In the sweat of thy face shall thou eat bread. . . . The white man must work to keep his children and pay his taxes.” In the middle background, the Freedmen’s Bureau looks like the Capitol, and the pillars are inscribed with racist assumptions of things blacks value, like “rum,” “idleness,” and “white women.” On the right are estimates of the costs of the Freedmen’s Bureau and the bounties (fees for enlistment) given to both white and black Union soldiers.

|

|

The Freedmen’s Bureau engaged in many initiatives to ease the transition from slavery to freedom. It delivered food to blacks and whites alike in the South. It helped freed people gain labor contracts, a significant step in the creation of wage labor in place of slavery. It helped reunite families of freedmen, and it also devoted much energy to education, establishing scores of public schools where freed people and poor whites could receive both elementary and higher education. Respected institutions such as Fisk University, Hampton University, and Dillard University are part of the legacy of the Freedmen’s Bureau.

The Freedmen’s Bureau, as shown in this 1866 illustration from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, created many schools for black elementary school students. Many of the teachers who provided instruction in these southern schools, though by no means all, came from northern states. Source: Wikimedia Commons

BLACK CODES

In 1865 and 1866, as Johnson announced the end of Reconstruction, southern states began to pass a series of discriminatory state laws collectively known as black codes. While the laws varied in both content and severity from state to state, the goal of the laws remained largely consistent. In effect, these codes were designed to maintain the social and economic structure of racial slavery in the absence of slavery itself. The laws codified white supremacy by restricting the civic participation of freed slaves—depriving them of the right to vote, the right to serve on juries, the right to own or carry weapons, and, in some cases, even the right to rent or lease land.

Black codes used a variety of tactics to tie freed slaves to the land. To work, the freed slaves were forced to sign contracts with their employer. These contracts prevented blacks from working for more than one employer. This meant that, unlike in a free labor market, blacks could not positively influence wages and conditions by choosing to work for the employer who gave them the best terms. The predictable outcome was that freed slaves were forced to work for very low wages. With such low wages, and no ability to supplement income with additional work, workers were reduced to relying on loans from their employers. The debt that these workers incurred ensured that they could never escape from their condition. Those formerly enslaved people who attempted to violate these contracts could be fined or beaten. Those who refused to sign contracts at all could be arrested for vagrancy and then made to work for no wages, essentially being reduced to the very definition of a slave.

The black codes left no doubt that the former breakaway Confederate states intended to maintain white supremacy at all costs. These draconian state laws helped spur the congressional Joint Committee on Reconstruction into action. Its members felt that ending slavery with the Thirteenth Amendment did not go far enough. Congress extended the life of the Freedmen’s Bureau to combat the black codes and in April 1866 passed the first Civil Rights Act, which established the citizenship of African Americans. This was a significant step that contradicted the Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decision, which declared that blacks could never be citizens. The law also gave the federal government the right to intervene in state affairs to protect the rights of citizens, and thus, of African Americans. Despite the Civil Rights Act, the black codes endured, forming the foundation of the racially discriminatory Jim Crow segregation policies that impoverished generations of African Americans.

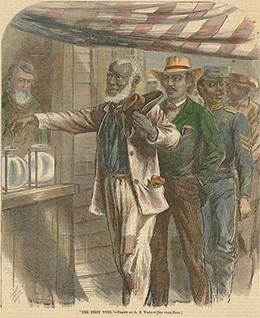

The First Vote, by Alfred R. Waud, appeared in Harper’s Weekly in 1867. Fear of African Americans voting was a key factor in the evolution of Black Codes and the rise of the KKK. Source: Wikimedia Commons

THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT

Because it differed from the Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott, questions swirled about the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act of 1866. Seeking to overcome all legal questions, Radical Republicans drafted a constitutional amendment with provisions that followed those of the 1866 Civil Rights Act. On July 28, 1868, this Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified. The amendment grants citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States” which included formerly enslaved people who had just been freed after the Civil War. The amendment had been rejected by most Southern states but was ratified by the required three-fourths of the states. Known as the “Reconstruction Amendment,” it forbids any state to deny any person “life, liberty or property, without due process of law” or to “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. It gave citizens equal protection under both the state and federal law, overturning the Dred Scott decision. It eliminated the three-fifths compromise of the 1787 Constitution, whereby enslaved people had been counted as three-fifths of a free white person, and it reduced the number of House representatives and Electoral College electors for any state that denied suffrage to any adult male inhabitant, black or white.

7.5 Section Summary

The conflict between President Johnson and the Republican-controlled Congress over the proper steps to be taken with the defeated Confederacy grew in intensity in the years immediately following the Civil War. While the president concluded that all that needed to be done in the South had been done by early 1866, Congress forged ahead to stabilize the defeated Confederacy and extend to freed people citizenship and equality before the law. Congress prevailed over Johnson’s vetoes as the friction between the president and the Republicans increased

7.6 Radical Reconstruction, 1867–1872

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the purpose of the second phase of Reconstruction and some of the key legislation put forward by Congress

- Describe the impeachment of President Johnson

- Discuss the benefits and drawbacks of the Fifteenth Amendment

During the Congressional election in the fall of 1866, Republicans gained even greater victories. This was due in large measure to the northern voter opposition that had developed toward President Johnson. Leading Radical Republicans in Congress envisioned a much more expansive change in the South. They considered that the southern states had forfeited their rights as states when they seceded, and were no more than conquered territory that the federal government could organize as it wished.

THE RECONSTRUCTION ACTS

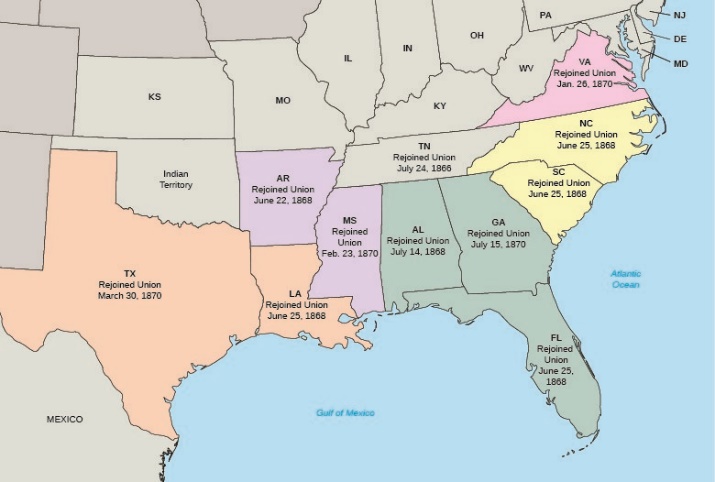

The 1867 Military Reconstruction Act, which encompassed the vision of Radical Republicans, set a new direction for Reconstruction in the South. Republicans saw this law, and three supplementary laws passed by Congress that year, called the Reconstruction Acts, as a way to deal with the disorder in the South. The 1867 act divided the ten southern states that had yet to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment into five military districts (Tennessee had already been readmitted to the Union by this time and so was excluded from these acts). Martial law was imposed, and a Union general commanded each district. These generals and twenty thousand federal troops stationed in the districts were charged with protecting freed people.

This map shows the five military districts established by the 1867 Military Reconstruction Act and the date each state rejoined the Union. Tennessee was not included in the Reconstruction Acts as it had already been readmitted to the Union at the time of their passage. Source: Wikimedia Commons

THE FIFTEENTH AMENDMENT

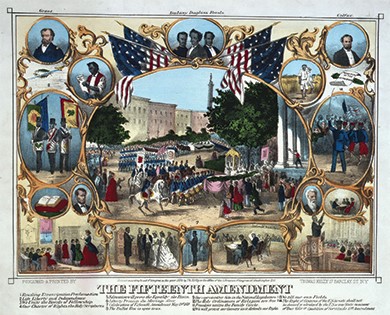

In November 1868, Ulysses S. Grant, the Union’s war hero, easily won the presidency in a landslide victory. Though Grant did not side with the Radical Republicans, his victory allowed the continuance of the Radical Reconstruction program. In the winter of 1869, Republicans introduced another constitutional amendment, the third of the Reconstruction era. With the Fifteenth Amendment, they sought to extend to black men the right to vote.

The amendment directed that “[t]he right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” The amendment granted universal manhood suffrage—the right of all men to vote—and crucially identified black men, including those who had been formerly enslaved people, as deserving the right to vote. This, the third and final of the Reconstruction amendments, was ratified in 1870. With the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, many believed that the process of restoring the Union was safely coming to a close and that the rights of freed slaves were finally secure. African American communities expressed great hope as they celebrated what they understood to be a national confirmation of their unqualified citizenship.

“The Fifteenth Amendment. Celebrated May 19th, 1870,” a commemorative print by Thomas Kelly, celebrates the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment with a series of vignettes highlighting black rights and those who championed them. Portraits include Ulysses S. Grant, Abraham Lincoln, and John Brown, as well as black leaders Martin Delany, Frederick Douglass, and Hiram Revels. Vignettes include the celebratory parade for the amendment’s passage, “The Ballot Box is open to us,” and “Our representative Sits in the National Legislature.” Source: Wikimedia Commons

WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE

While the Fifteenth Amendment may have been greeted with applause in many corners, leading women’s rights activists, who had been campaigning for decades for the right to vote, saw it as a major disappointment. Following the war, women and men, white and black, had formed the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) for the expressed purpose of securing “equal Rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color or sex.” As Congress debated the language of the Fifteenth Amendment, some held out hope that it would finally extend the franchise to women. Those hopes were dashed when Congress adopted the final language.

The consequence of these frustrated hopes was the effective split of a civil rights movement that had once been united in support of African Americans and women. Some women’s rights leaders and AERA members like Lucy Stone and Henry Browne Blackwell, believed that more time was needed to bring about female suffrage. Others demanded immediate action. They felt greatly aggrieved at the fact that other abolitionists, with whom they had worked closely for years, did not demand that women be included in the language of the amendments. Thus, in 1869, Stanton and Anthony helped organize a new organization, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), dedicated to ensuring that women gained the right to vote immediately, not at some future, undetermined date.

|

|

DEFINING “AMERICAN” |

|

Constitution of the National Woman Suffrage Association Despite the Fifteenth Amendment’s failure to guarantee female suffrage, women did gain the right to vote in western territories, with the Wyoming Territory leading the way in 1869. One reason for this was a belief that giving women the right to vote would provide a moral compass to the otherwise lawless western frontier. Extending the right to vote in western territories also provided an incentive for white women to emigrate to the West, where they were scarce. However, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and others believed that immediate action on the national front was required, leading to the organization of the NWSA and its resulting constitution. ARTICLE 1. —This organization shall be called the National Woman Suffrage Association. ARTICLE 2. —The object of this Association shall be to secure STATE and NATIONAL protection for women citizens in the exercise of their right to vote. ARTICLE 3. —All citizens of the United States subscribing to this Constitution, and contributing not less than one dollar annually, shall be considered members of the Association, with the right to participate in its deliberations. ARTICLE 4. —The officers of this Association shall be a President, Vice-Presidents from each of the States and Territories, Corresponding and Recording Secretaries, a Treasurer, an Executive Committee of not less than five, and an Advisory Committee consisting of one or more persons from each State and Territory. OFFICERS OF THE NATIONAL WOMAN SUFFRAGE ASSOCIATION. PRESIDENT. SUSAN B. ANTHONY, Rochester, N. Y. |

|

BLACK POLITICAL ACHIEVEMENTS

Black voter registration in the late 1860s and the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment finally brought what Lincoln had characterized as “a new birth of freedom.” Union Leagues, fraternal groups founded in the North that promoted loyalty to the Union and the Republican Party during the Civil War, expanded into the South after the war and were transformed into political clubs that served both political and civic functions. As centers of the black communities in the South, the leagues became vehicles for the dissemination of information, acted as mediators between members of the black community and the white establishment, and served other practical functions like helping to build schools and churches for the community they served. As extensions of the Republican Party, these leagues worked to enroll newly enfranchised black voters, campaign for candidates, and generally help the party win elections. The political activities of the leagues launched a great many African Americans and former slaves into politics throughout the South. For the first time, blacks began to hold political office, and several were elected to the U.S. Congress. In the 1870s, fifteen members of the House of Representatives and two senators were black.

Though the fact of their presence was dramatic and important, the few African American representatives and senators who served in Congress during Reconstruction represented only a tiny fraction of the many hundreds, possibly thousands, of blacks who served in a great number of capacities at the local and state levels. The South during the early 1870s brimmed with freed once enslaved and freeborn blacks serving as school board commissioners, county commissioners, clerks of court, board of education and city council members, justices of the peace, constables, coroners, magistrates, sheriffs, auditors, and registrars. This wave of local African American political activity contributed to and was accompanied by a new concern for the poor and disadvantaged in the South. The southern Republican leadership did away with the hated black codes, undid the work of white supremacists, and worked to reduce obstacles confronting freed people.

White southerners reacted with outrage at the changes imposed upon them. The sight of once enslaved blacks serving in positions of authority as sheriffs, congressmen, and city council members stimulated great resentment at the process of Reconstruction and its undermining of the traditional social and economic foundations of the South. They complained of profligate corruption on the part of vengeful once enslaved blacks and greedy northerners looking to fill their pockets with the South’s riches. The sense that the South had been unfairly sacrificed to northern vice and black vengeance, despite a wealth of evidence to the contrary, persisted for many decades.

The reality is that the opposite was true. White southerners orchestrated a sometimes violent and generally successful counterrevolution against Reconstruction policies in the South beginning in the 1860s. Those who worked to change and modernize the South typically did so under the stern gaze of exasperated whites and threats of violence. Black Republican officials in the South were frequently terrorized, assaulted, and even murdered with impunity by organizations like the Ku Klux Klan. When not ignoring the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments altogether, white leaders often used trickery and fraud at the polls to get the results they wanted. As Reconstruction came to a close, these methods came to define southern life for African Americans for nearly a century afterwards.

Hiram Revels served as a preacher throughout the Midwest before settling in Mississippi in 1866. When he was elected by the Mississippi state legislature in 1870, he became the country’s first African American senator. Source: Wikimedia Commons

|

|

DEFINING “AMERICAN” |

|

Senator Revels on Segregated Schools in Washington, DC Hiram R. Revels became the first African American to serve in the U.S. Senate in 1870. In 1871, he gave the following speech about Washington’s segregated schools before Congress. “Will establishing such [desegregated] schools as I am now advocating in this District harm our white friends? . . . By some it is contended that if we establish mixed schools here a great insult will be given to the white citizens, and that the white schools will be seriously damaged. . . . When I was on a lecturing tour in the state of Ohio . . . [o]ne of the leading gentlemen connected with the schools in that town came to see me. . . . He asked me, “Have you been to New England, where they have mixed schools?” I replied, “I have sir.” “Well,” said he, “please tell me this: does not social equality result from mixed schools?” “No, sir; very far from it,” I responded. “Why,” said he, “how can it be otherwise?” I replied, “I will tell you how it can be otherwise, and how it is otherwise. Go to the schools and you see there white children and colored children seated side by side, studying their lessons, standing side by side and reciting their lessons, and perhaps in walking to school they may walk together; but that is the last of it. The white children go to their homes; the colored children go to theirs; and on the Lord’s day you will see those colored children in colored churches, and the white family, you will see the white children there, and the colored children at entertainments given by persons of their color.” I aver, sir, that mixed schools are very far from bringing about social equality.” |

|

BUILDING BLACK COMMUNITIES

The degraded status of black men and women had placed them outside the limits of what antebellum southern whites considered appropriate gender roles and familial hierarchies. The marriages of enslaved blacks did not enjoy legal recognition. Enslaved men were humiliated and deprived of authority and of the ability to protect enslaved women, who were frequently exposed to the brutality and sexual domination of white masters and vigilantes alike. Enslaved parents could not protect their children, who could be bought, sold, put to work, brutally disciplined, and abused without their consent; parents, too, could be sold away from their children. Moreover, the division of labor idealized in white southern society, in which men worked the land and women performed the role of domestic caretaker, was null and void where slaves were concerned. Both slave men and women were made to perform hard labor in the fields.

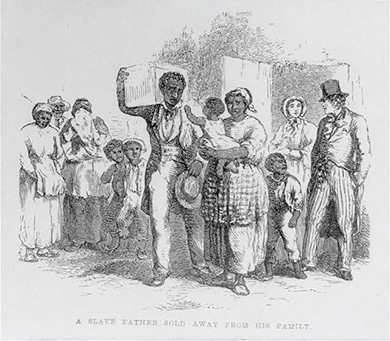

After emancipation, many fathers who had been sold from their families as slaves—a circumstance illustrated in the engraving above, which shows a male slave forced to leave his wife and children—set out to find those lost families and rebuild their lives. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In the Reconstruction era, African Americans embraced the right to enjoy the family bonds and the expression of gender norms they had been systematically denied. Many thousands of freed black men who had been separated from their families as once enslaved people took to the road to find their long-lost spouses and children and renew their bonds. In one instance, a journalist reported having interviewed a once enslaved man who traveled over six hundred miles on foot in search of the family that was taken from him while in bondage. Couples that had been spared separation quickly set out to legalize their marriages, often by way of the Freedmen’s Bureau, now that this option was available. Those who had no families would sometimes relocate to southern towns and cities, so as to be part of the larger black community where churches and other mutual aid societies offered help and camaraderie.

SHARECROPPING

Most freed people stayed in the South on the lands where their families and loved ones had worked for generations as enslaved people. The end of slavery meant the transition to wage labor. However, this conversion did not entail a new era of economic independence for those who had once been enslaved. While they no longer faced relentless toil under the lash, freed people emerged from slavery without any money and needed farm implements, food, and other basic necessities to start their new lives. Under the crop-lien system, store owners extended credit to farmers under the agreement that the debtors would pay with a portion of their future harvest. However, the creditors charged high interest rates, making it even harder for freed people to gain economic independence.

Throughout the South, sharecropping took root, a crop-lien system that worked to the advantage of landowners. Under the system, freed people rented the land they worked, often on the same plantations where they had been enslaved people. Some landless whites also became sharecroppers. Sharecroppers paid their landlords with the crops they grew, often as much as half their harvest. Sharecropping favored the landlords and ensured that freed people could not attain independent livelihoods. The year-to-year leases meant no incentive existed to substantially improve the land, and high interest payments siphoned additional money away from the farmers. Sharecroppers often became trapped in a never-ending cycle of debt, unable to buy their own land and unable to stop working for their creditor because of what they owed. The consequences of sharecropping affected the entire South for many generations, severely limiting economic development and ensuring that the South remained an agricultural backwater.

7.6 Section Summary

Though President Johnson declared Reconstruction complete less than a year after the Confederate surrender, members of Congress disagreed. Republicans in Congress began to implement their own plan of bringing law and order to the South through the use of military force and martial law. Radical Republicans who advocated for a more equal society pushed their program forward as well, leading to the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, which finally gave blacks the right to vote. The new amendment empowered black voters, who made good use of the vote to elect black politicians. It disappointed female suffragists, however, who had labored for years to gain women’s right to vote. By the end of 1870, all the southern states under Union military control had satisfied the requirements of Congress and been readmitted to the Union.

7.7 The Collapse of Reconstruction

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain the reasons for the collapse of Reconstruction

- Describe the efforts of white southern “redeemers” to roll back the gains of Reconstruction

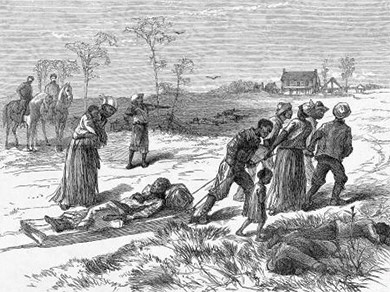

The effort to remake the South generated a brutal reaction among southern whites, who were committed to keeping blacks in a subservient position. To prevent blacks from gaining economic ground and to maintain cheap labor for the agricultural economy, an exploitative system of sharecropping spread throughout the South. Domestic terror organizations, most notably the Ku Klux Klan, employed various methods (arson, whipping, murder) to keep freed people from voting and achieving political, social, or economic equality with whites.

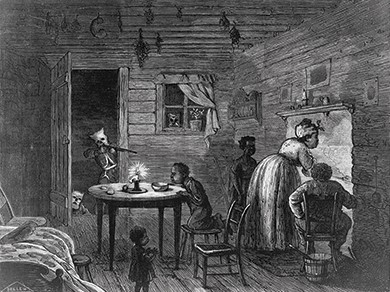

This illustration by Frank Bellew, captioned “Visit of the Ku-Klux,” appeared in Harper’s Weekly in 1872. A hooded Klansman surreptitiously points a rifle at an unaware black family in their home. Source: Wikimedia Commons

THE “INVISIBLE EMPIRE OF THE SOUTH”

Paramilitary white-supremacist terror organizations in the South helped bring about the collapse of Reconstruction, using violence as their primary weapon. The “Invisible Empire of the South,” or Ku Klux Klan, stands as the most notorious. The Klan was founded in 1866 as an oath-bound fraternal order of Confederate veterans in Tennessee. The Klan terrorized newly freed blacks to deter them from exercising their citizenship rights and freedoms. Other anti-black vigilante groups around the South began to adopt the Klan name and perpetrate acts of unspeakable violence against anyone they considered a tool of Reconstruction. Other groups, like the Red Shirts from Mississippi and the Knights of the White Camelia and the White League, both from Louisiana, also sprang up at this time. The Klan and similar organizations also worked as an extension of the Democratic Party to win elections.

To preserve a white-dominated society, Klan members punished blacks for attempting to improve their station in life or acting “uppity.” Klan tactics included riding out to victims’ houses, masked and armed, and firing into the homes or burning them down. To prevent freed people from attaining an education, the Klan burned public schools. In an effort to stop blacks from voting, the Klan murdered, whipped, and otherwise intimidated freed people and their white supporters. Thus, the Klan also directed their energies toward persecuting people they considered carpetbaggers, a term of abuse applied to northerners accused of having come to the South to acquire wealth through political power at the expense of southerners. Southern whites who supported Reconstruction, known as scalawags, also generated great hostility as traitors to the South. They, too, became targets of the Klan and similar groups.

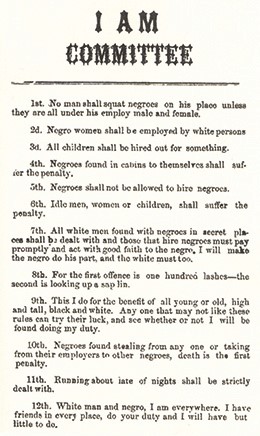

The Ku Klux Klan posted circulars such as this 1867 West Virginia broadside to warn blacks and white sympathizers of the power and ubiquity of the Klan. Source: Wikimedia Commons

“REDEEMERS” AND THE END OF RECONSTRUCTION

Many southern whites saw the KKK as an instrument of order in a world turned upside down. They felt humiliated by the process of Radical Reconstruction and the way Republicans had upended southern society, placing blacks in positions of authority while taxing large landowners to pay for the education of once enslaved people. Those committed to rolling back the tide of Radical Reconstruction in the South called themselves redeemers, a label that expressed their desire to redeem their states from northern control and to restore the antebellum social order whereby blacks were kept safely under the boot heel of whites. They represented the Democratic Party in the South and worked tirelessly to end what they saw as an era of “negro misrule.” By 1877, they had succeeded in bringing about the “redemption” of the South, effectively destroying the dream of Radical Reconstruction.

|

|

MY STORY |

|

Abram Colby on the Methods of the Ku Klux Klan The following statements are from the October 27, 1871, testimony of fifty-two-year-old formerly enslaved person Abram Colby, which the joint select committee investigating the Klan took in Atlanta, Georgia. Colby had been elected to the lower house of the Georgia State legislature in 1868. On the 29th of October, they came to my house and broke my door open, took me out of my bed and took me to the woods and whipped me three hours or more and left me in the woods for dead. They said to me, “Do you think you will ever vote another damned Radical ticket?” I said, “I will not tell you a lie.” They said, “No; don’t tell a lie.” . . . I said, “If there was an election to-morrow, I would vote the Radical ticket.” They set in and whipped me a thousand licks more, I suppose. . . . They said I had influence with the negroes of other counties, and had carried the negroes against them. About two days before they whipped me they offered me $5,000 to turn and go with them, and said they would pay me $2,500 cash if I would turn and let another man go to the legislature in my place. . . . I would have come before the court here last week, but I knew it was no use for me to try to get Ku-Klux condemned by Ku-Klux, and I did not come. Mr. Saunders, a member of the grand jury here last week, is the father of one of the very men I knew whipped me. . . . They broke something inside of me, and the doctor has been attending to me for more than a year. Sometimes I cannot get up and down off my bed, and my left hand is not of much use to me. —Abram Colby testimony, Joint Select Committee Report, 1872 |

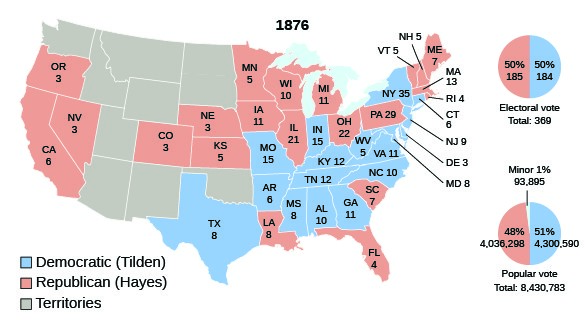

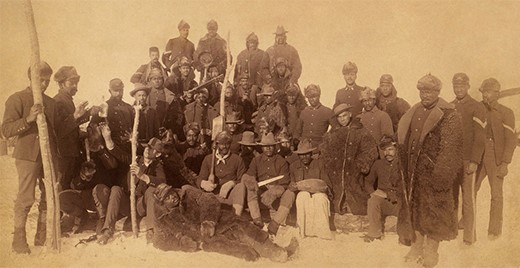

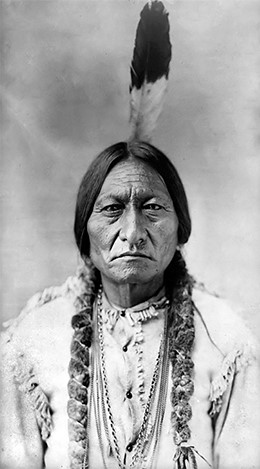

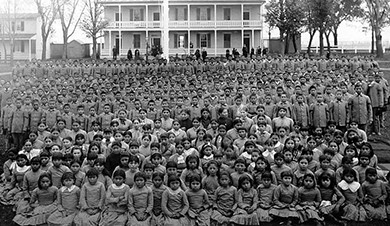

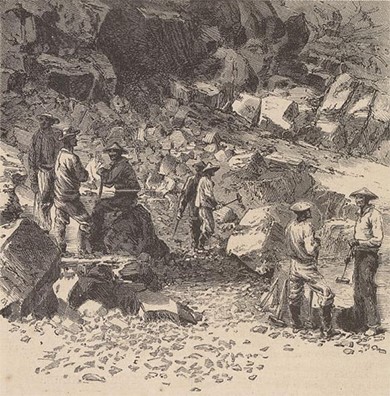

|