14 Chapter 14: The US in Modern Times: Culture Wars and the Challenges of the Twenty-First Century, 1992-2022

The US in Modern Times: Culture Wars and the Challenges of the Twenty-First Century, 1992-2022

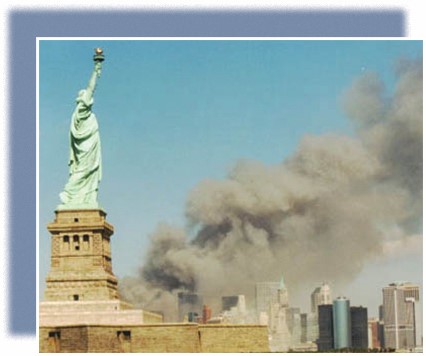

In 2001, almost three thousand people died as a result of the September 11 attacks, when members of the terrorist group al-Qaeda hijacked four planes as part of a coordinated attack on sites in New York City and Washington, DC. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Chapter Outline

Introduction, Watch and Learn, Questions to Guide Your Reading

14.1 Bill Clinton and the New Economy

14.2 The War on Terror

14.3 The Domestic Mission

14.4 New Century, Old Disputes

14.5 Hope and Change

14.6 President Trump and Covid-19

Summary Timelines, Chapter 14 Self-Test, Chapter 14 Key Terms Crossword Puzzle

Introduction

On the morning of September 11, 2001, hopes that the new century would leave behind the conflicts of the previous one were dashed when two hijacked airliners crashed into the twin towers of New York’s World Trade Center. When the first plane struck the north tower, many assumed that the crash was a horrific accident. But then a second plane hit the south tower less than thirty minutes later. People on the street watched in horror, as some of those trapped in the burning buildings jumped to their deaths and the enormous towers collapsed into dust. In the photo above, the Statue of Liberty appears to look on helplessly, as thick plumes of smoke obscure the Lower Manhattan skyline. The events set in motion by the September 11 attacks would raise fundamental questions about the United States’ role in the world, the extent to which privacy should be protected at the cost of security, the definition of exactly who is an American, and the cost of liberty.

Watch and Learn

- The Clinton Years, or the 1990s

- Rap and Hip Hop

- Terrorism, War, and Bush 43

- Hurricane Katrina

- Obamanation

- Barack Obama

- Black Lives Matter

Questions to Guide Your Reading

- In what ways was Bill Clinton a traditional Democrat in the style of Kennedy and Johnson? In what ways was he a conservative, like Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush?

- Describe American involvement in global affairs during this period. How did American foreign policy change and evolve between 1980 and 2000, in both its focus and its approach?

- How have conservatives fared in their efforts to defend “American” culture against an influx of immigrants in the twenty-first century?

- In what ways were Barack Obama’s ideas regarding the economy, education, and the environment similar to those of Bush, his Republican predecessor? In what ways were they different?

- In what ways has the United States become a more heterogeneous and inclusive place in the twenty-first century? In what ways has it become more homogenous and exclusive?

- What does the Presidency of Donald Trump reveal about the state of the country in the 21st century? What trends does it reflect?

- How did responses to the Covid-19 Pandemic reflect a divided America?

14.1 Bill Clinton and the New Economy

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain political partisanship, antigovernment movements, and economic developments during the Clinton administration

- Discuss President Clinton’s foreign policy

- Explain how George W. Bush won the election of 2000

By 1992, many had come to doubt that President George H. W. Bush could solve America’s problems. He had alienated conservative Republicans by breaking his pledge not to raise taxes, and some faulted him for failing to remove Saddam Hussein from power during Operation Desert Storm. Furthermore, despite living much of his adult life in Texas, he could not overcome the stereotypes associated with his privileged New England and Ivy League background, which hurt him among working-class Reagan Democrats.

THE ROAD TO THE WHITE HOUSE

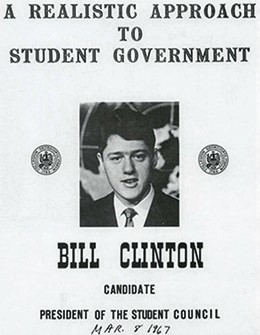

The contrast between George H. W. Bush and William Jefferson Clinton could not have been greater. Bill Clinton was a baby boomer born in 1946 in Hope, Arkansas. His biological father died in a car wreck three months before he was born. When he was a boy, his mother married Roger Clinton, an alcoholic who abused his family. However, despite a troubled home life, Clinton was an excellent student. He took an interest in politics from an early age. On a high school trip to Washington, DC, he met his political idol, President Kennedy. As a student at Georgetown University, he supported both the civil rights and antiwar movements and ran for student council president.

In 1968, Clinton received a prestigious Rhodes scholarship to Oxford University. From Oxford he moved on to Yale, where he earned his law degree in 1973. He returned to Arkansas and became a professor at the University of Arkansas’s law school. The following year, he tried his hand at state politics, running for Congress, and was narrowly defeated. In 1977, he became attorney general of Arkansas and was elected governor in 1978. Losing the office to his Republican opponent in 1980, he retook the governor’s mansion in 1982 and remained governor of Arkansas until 1992, when he announced his candidacy for president.

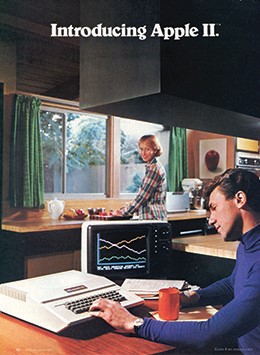

During his 1967 campaign for student council president at Georgetown University, Bill Clinton told those who voted for him that he would invite them to the White House when he became president of the United States. He kept his promise. Source: Wikimedia Commons

During his campaign, Bill Clinton described himself as a New Democrat, a member of a faction of the Democratic Party that, like the Republicans, favored free trade and deregulation. He tried to appeal to the middle class by promising higher taxes on the rich and reform of the welfare system. Although Clinton garnered only 43 percent of the popular vote, he easily won in the Electoral College with 370 votes to President Bush’s 188. Texas billionaire H. Ross Perot won 19 percent of the popular vote, the best showing by any third-party candidate since 1912. The Democrats took control of both houses of Congress.

“IT’S THE ECONOMY, STUPID”

Clinton took office towards the end of a recession. His administration’s plans for fixing the economy included limiting spending and cutting the budget to reduce the nation’s $60 billion deficit, keeping interest rates low to encourage private investment, and eliminating protectionist tariffs. Clinton also hoped to improve employment opportunities by allocating more money for education. In his first term, he expanded the Earned Income Tax Credit, which lowered the tax obligations of working families who were just above the poverty line. Addressing the budget deficit, the Democrats in Congress passed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 without a single Republican vote. The act raised taxes for the top 1.2 percent of the American people, lowered them for fifteen million low-income families, and offered tax breaks to 90 percent of small businesses.

Clinton also strongly supported ratification of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), a treaty that eliminated tariffs and trade restrictions among the United States, Canada, and Mexico. The treaty had been negotiated by the Bush administration, and the leaders of all three nations had signed it in December 1992. However, because of strong opposition from American labor unions and some in Congress who feared the loss of jobs to Mexico, the treaty had not been ratified by the time Clinton took office. To allay the concerns of unions, he added an agreement to protect workers and also one to protect the environment. Congress ratified NAFTA late in 1993. The result was the creation of the world’s largest common market in terms of population, including some 425 million people.

During Clinton’s administration, the nation began to experience the longest period of economic expansion in its history, almost ten consecutive years. Year after year, job growth increased, and the deficit shrank. Increased tax revenue and budget cuts turned the annual national budget deficit from close to $290 billion in 1992 to a record budget surplus of over $230 billion in 2000. Reduced government borrowing freed up capital for private-sector use, and lower interest rates in turn fueled more growth. During the Clinton years, more people owned homes than ever before in the country’s history (67.7 percent). Inflation dipped to 2.3 percent and the unemployment rate declined, reaching a thirty-year low of 3.9 percent in 2000. Much of the prosperity of the 1990s was related to technological change and the advent of new information systems. In 1994, the Clinton administration became the first to launch an official White House website and join the revolution of the electronically mediated world.

|

|

AMERICANA |

|

Hope and Anxiety in the Information Age In the late 1970s and early 1980s, computer manufacturers like Apple, Commodore, and Tandy began offering fully assembled personal computers. (Previously, personal computing had been accessible only to those adventurous enough to buy expensive kits that had to be assembled and programmed.) In short order, computers became a fairly common sight in businesses and upper-middle-class homes. Soon, computer owners, even young kids, were launching their own electronic bulletin board systems, small-scale networks that used modems and phone lines, and sharing information in ways not dreamed of just decades before. Computers, it seemed, held out the promise of a bright, new future for those who knew how to use them. Casting shadows over the bright dreams of a better tomorrow were fears that the development of computer technology would create a dystopian future in which technology became the instrument of society’s undoing. Film audiences watched a teenaged Matthew Broderick hacking into a government computer and starting a nuclear war in War Games, Angelina Jolie being chased by a computer genius bent on world domination in Hackers, and Sandra Bullock watching helplessly as her life is turned inside out by conspirators who manipulate her virtual identity in The Net. Clearly, the idea of digital network connections as the root of our demise resonated in this period of rapid technological change.

|

|

DOMESTIC ISSUES

In addition to shifting the Democratic Party to the moderate center on economic issues, Clinton tried to break new ground on a number of domestic issues and make good on traditional Democratic commitments to the disadvantaged, minority groups, and women. At the same time, he faced the challenge of domestic terrorism when a federal building in Oklahoma City was bombed, killing 168 people and injuring hundreds more.

Healthcare Reform

An important and popular part of Clinton’s domestic agenda was healthcare reform that would make universal healthcare a reality. When the plan was announced in September of the president’s first year in office, pollsters and commentators both assumed it would sail through. Many were unhappy with the way the system worked in the United States, where the cost of health insurance seemed increasingly unaffordable for the middle class. Clinton appointed his wife, Hillary Clinton, a Yale Law School graduate and accomplished attorney, to head his Task Force on National Health Care Reform in 1993. The 1,342-page Health Security Act presented to Congress that year sought to offer universal coverage. All Americans were to be covered by a healthcare plan that could not reject them based on preexisting medical conditions. Employers would be required to provide healthcare for their employees. Limits would be placed on the amount that people would have to pay for services; the poor would not have to pay at all.

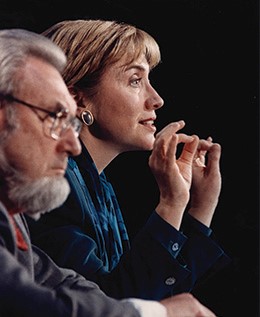

C. Everett Koop, who had served as surgeon general under Ronald Reagan and was a strong advocate of healthcare reform, helped First Lady Hillary Clinton promote the Health Security Act in the fall of 1993. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The outlook for the plan looked good in 1993; it had the support of a number of institutions like the American Medical Association and the Health Insurance Association of America. But in relatively short order, the political winds changed. As budget battles distracted the administration and the midterm elections of 1994 approached, Republicans began to recognize the strategic benefits of opposing reform. Soon they were mounting fierce opposition to the bill. Moderate conservatives dubbed the reform proposals “Hillarycare” and argued that the bill was an unwarranted expansion of the powers of the federal government that would interfere with people’s ability to choose the healthcare provider they wanted. Those further to the right argued that healthcare reform was part of a larger and nefarious plot to control the public.

To rally Republican opposition to Clinton and the Democrats, Newt Gingrich and Richard “Dick” Armey, two of the leaders of the Republican minority in the House of Representatives, prepared a document entitled Contract with America, signed by all but two of the Republican representatives. It listed eight specific legislative reforms or initiatives the Republicans would enact if they gained a majority in Congress in the 1994 midterm elections.

Lacking support on both sides, the healthcare bill was never passed and died in Congress. The reform effort finally ended in September 1994. Dislike of the proposed healthcare plan on the part of conservatives and the bold strategy laid out in the Contract with America enabled the Republican Party to win seven Senate seats and fifty-two House seats in the November elections. The Republicans then used their power to push for conservative reforms. One such piece of legislation was the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, signed into law in August 1996. The act set time limits on welfare benefits and required most recipients to begin working within two years of receiving assistance.

Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell

Although Clinton had campaigned as an economically conservative New Democrat, he was thought to be socially liberal and, just days after his victory in the 1992 election, he promised to end the fifty-year ban on gays and lesbians serving in the military. However, in January 1993, after taking the oath of office, Clinton amended his promise in order to appease conservatives. Instead of lifting the longstanding ban, the armed forces would adopt a policy of “don’t ask, don’t tell.” Those on active duty would not be asked their sexual orientation and, if they were gay, they were not to discuss their sexuality openly or they would be dismissed from military service. This compromise satisfied neither conservatives seeking the exclusion of gays nor the gay community, which argued that homosexuals, like heterosexuals, should be able to live without fear of retribution because of their sexuality.

Clinton again proved himself willing to appease political conservatives when he signed into law the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) in September 1996, after both houses of Congress had passed it with such wide margins that a presidential veto could easily be overridden. DOMA defined marriage as a heterosexual union and denied federal benefits to same-sex couples. It also allowed states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages granted by other states. When Clinton signed the bill, he was personally opposed to same-sex marriage. Nevertheless, he disliked DOMA and later called for its repeal. He also later changed his position on same-sex marriage. On other social issues, however, Clinton was more liberal. He appointed openly gay and lesbian men and women to important positions in government and denounced discrimination against people with AIDS. He supported the idea of the ERA and believed that women should receive pay equal to that of men doing the same work. He opposed the use of racial quotas in employment, but he declared affirmative action programs to be necessary.

As a result of his economic successes and his moderate social policies, Clinton defeated Senator Robert Dole in the 1996 presidential election. With 49 percent of the popular vote and 379 electoral votes, he became the first Democrat to win reelection to the presidency since Franklin Roosevelt. Clinton’s victory was partly due to a significant gender gap between the parties, with women tending to favor Democratic candidates. In 1992, Clinton won 45 percent of women’s votes compared to Bush’s 38 percent, and in 1996, he received 54 percent of women’s votes while Dole won 38 percent.

Domestic Terrorism

The fears of those who saw government as little more than a necessary evil appeared to be confirmed in the spring of 1993, when federal and state law enforcement authorities laid siege to the compound of a religious sect called the Branch Davidians near Waco, Texas. The group, which believed the end of world was approaching, was suspected of weapons violations and resisted search-and-arrest warrants with deadly force. A standoff developed that lasted nearly two months and was captured on television each day. A final assault on the compound was made on April 19, and seventy-six men, women, and children died in a fire probably set by members of the sect. Many others committed suicide or were killed by fellow sect members.

During the siege, many antigovernment and militia types came to satisfy their curiosity or show support for those inside. One was Timothy McVeigh, a former U.S. Army infantry soldier. McVeigh had served in Operation Desert Storm in Iraq, earning a bronze star, but he became disillusioned with the military and the government when he was deemed psychologically unfit for the Army Special Forces. He was convinced that the Branch Davidians were victims of government terrorism, and he and his coconspirator, Terry Nichols, determined to avenge them.

Two years later, on the anniversary of the day that the Waco compound burned to the ground, McVeigh parked a rented truck full of explosives in front of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City and blew it up. More than 600 people were injured in the attack and 168 died, including nineteen children at the daycare center inside. McVeigh hoped that his actions would spark a revolution against government control. He and Nichols were both arrested and tried, and McVeigh was executed on June 11, 2001, for the worst act of terrorism committed on American soil.

The remains of automobiles stand in front of the bombed federal building in Oklahoma City in 1995 (a). More than three hundred nearby buildings were damaged by the blast, an attack perpetrated at least partly to avenge the Waco siege (b) exactly two years earlier. Source: Wikimedia Commons

CLINTON AND AMERICAN HEGEMONY

For decades, the contours of the Cold War had largely determined U.S. action abroad. Strategists saw each coup, revolution, and civil war as part of the larger struggle between the United States and the Soviet Union. But with the Soviet Union vanquished, the United States was suddenly free of this paradigm, and President Clinton could see international crises in the Middle East, the Balkans, and Africa on their own terms and deal with them accordingly. He envisioned a post-Cold War role in which the United States used its overwhelming military superiority and influence as global policing tools to preserve the peace. This foreign policy strategy had both success and failure.

One notable success was a level of peace in the Middle East. In September 1993, at the White House, Yitzhak Rabin, prime minister of Israel, and Yasser Arafat, chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization, signed the Oslo Accords, granting some self-rule to Palestinians living in the Israeli-occupied territories of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. A year later, the Clinton administration helped facilitate the second settlement and normalization of relations between Israel and Jordan.

Yitzhak Rabin (left) and Yasser Arafat (right), shown with Bill Clinton, signed the Oslo Accords at the White House on September 13, 1993. Rabin was killed two years later by an Israeli who opposed the treaty. Source: Wikimedia Commons

As a small measure of stability was brought to the Middle East, violence erupted in the Balkans. The Communist country of Yugoslavia had consisted of six provinces: Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Slovenia, Montenegro, and Macedonia. Each was occupied by a number of ethnic groups, some of which shared a history of hostile relations. With the breakdown of Communism elsewhere in Europe, Yugoslavia split as well. In 1991, Croatia, Slovenia, and Macedonia declared their independence. In 1992, Bosnia and Herzegovina did as well. Only Serbia and Montenegro remained united as the Serbian-dominated Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

Almost immediately, ethnic tensions within Bosnia and Herzegovina escalated into war when Yugoslavian Serbs aided Bosnian Serbs who did not wish to live in an independent Bosnia and Herzegovina. These Bosnian Serbs proclaimed the existence of autonomous Serbian regions within the country and attacked Bosnian Muslims and Croats. During the conflict, the Serbs engaged in genocide, described by some as “ethnic cleansing.” The brutal conflict also gave rise to the systematic rape of “enemy” women—generally Muslim women exploited by Serbian military or paramilitary forces. The International Criminal Tribunal of Yugoslavia estimated that between twelve thousand and fifty thousand women were raped during the war.

NATO eventually intervened in 1995, and Clinton agreed to U.S. participation in airstrikes against Bosnian Serbs. The United States, acting with other NATO members, launched an air campaign against Serbian-dominated Yugoslavia to stop it from attacking ethnic Albanians in Kosovo. Although these attacks were not sanctioned by the UN and were criticized by Russia and China, Yugoslavia withdrew its forces from Kosovo in June 1999.

The use of force did not always bring positive results. In 1993, the Clinton administration sent soldiers to capture a Somali warlord, Mohammed Farah Aidid, who was harassing and endangering the lives of aid workers. The resulting battle proved disastrous. A Black Hawk helicopter was shot down, and U.S. Army Rangers and members of Delta Force spent hours battling their way through the streets; eighty-four soldiers were wounded and nineteen died. The United States withdrew, leaving Somalia to struggle with its own anarchy.

The sting of the Somalia failure probably contributed to Clinton’s reluctance to send U.S. forces to end the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. During a civil war in 1980, the Hutu majority began to slaughter the Tutsi minority and their Hutu supporters. In 1998, while visiting Rwanda, Clinton apologized for having done nothing to save the lives of the 800,000 massacred in one hundred days of genocidal slaughter.

IMPEACHMENT

Public attention was diverted from Clinton’s foreign policing actions by a series of scandals that marked the last few years of his presidency. From the moment he entered national politics, his opponents had attempted to tie Clinton and his First Lady to a number of loosely defined improprieties. One accusation the Clintons could not shake was of possible improper involvement in a failed real estate venture associated with the Whitewater Development Corporation in Arkansas in the 1970s and 1980s. Kenneth Starr, a former federal appeals court judge, was appointed to investigate the matter in August 1994.

While Starr was never able to prove any wrongdoing, he soon turned up other allegations and his investigative authority was expanded. In May 1994, Paula Jones, a former Arkansas state employee, filed a sexual harassment lawsuit against Bill Clinton. Starr’s office began to investigate this case as well. When a federal court dismissed Jones’s suit in 1998, her lawyers promptly appealed the decision and submitted a list of other alleged victims of Clinton’s harassment. That list included the name of Monica Lewinsky, a young White House intern. Clinton denied under oath that they had had a sexual relationship and even went on national television to assure the American people that he had never had sexual relations with Lewinsky. However, after receiving a promise of immunity, Lewinsky turned over to Starr evidence of her affair with Clinton, and the president admitted he had indeed had inappropriate relations with her. He nevertheless denied that he had lied under oath.

In September, Starr reported to the House of Representatives that he believed Clinton had committed perjury. Voting along partisan lines, the Republican-dominated House of Representatives sent articles of impeachment to the Senate, charging Clinton with lying under oath and obstructing justice. In February 1998, the Senate voted forty-five to fifty-five on the perjury charge and fifty-fifty on obstruction of justice. Although acquitted, Clinton did become the first president to be found in contempt of court. Nevertheless, although he lost his law license, he remained a popular president and left office at the end of his second term with an approval rating of 66 percent, the highest of any U.S. president.

Floor proceedings in the U.S. Senate during the 1998 impeachment trial of Bill Clinton, who was narrowly acquitted of both charges. Source: Wikimedia Commons

THE ELECTION OF 2000

Despite Clinton’s high approval rating, his vice president and the 2000 Democratic nominee for president, Al Gore, was eager to distance himself from scandal. Unfortunately, he also alienated Clinton loyalists and lost some of the benefit of Clinton’s genuine popularity. Gore’s desire to emphasize his concern for morality led him to select Connecticut senator Joseph I. Lieberman as his running mate. Lieberman had been quick to denounce Clinton’s relationship with Monica Lewinsky. Consumer advocate Ralph Nader ran as the candidate of the Green Party, a party devoted to environmental issues and grassroots activism, and Democrats feared that he would attract votes that Gore might otherwise win.

On the Republican side, where strategists promised to “restore honor and dignity” to the White House, voters were divided between George W. Bush, governor of Texas and eldest son of former president Bush, and John McCain, an Arizona senator and Vietnam War veteran. Bush had the robust support of both the Christian Right and the Republican leadership. His campaign amassed large donations that it used to defeat McCain, himself an outspoken critic of the influence of money in politics. The nomination secured, Bush selected Dick Cheney, part of the Nixon and Ford administrations and secretary of defense under George H. W. Bush, as his running mate.

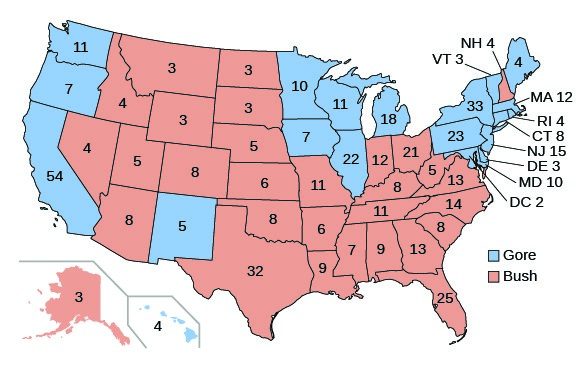

One hundred million votes were cast in the 2000 election, and Gore topped Bush in the popular vote by 540,000 ballots, or 0.5 percent. The race was so close that news reports declared each candidate the winner at various times during the evening. It all came down to Florida, where early returns called the election in Bush’s favor by a mere 527 of 5,825,000 votes. Whoever won Florida would get the state’s twenty-five electoral votes and secure the presidency.

The map shows the results of the 2000 U.S. presidential election. While Bush won in the majority of states, Gore dominated in the more populous ones, winning the popular vote overall. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Because there seemed to be irregularities in four counties traditionally dominated by Democrats, especially in largely African American precincts, Gore called for a recount of the ballots by hand. Florida’s secretary of state, Katherine Harris, set a deadline for the new vote tallies to be submitted, a deadline the counties could not meet. When the Democrats requested an extension, the Florida Supreme Court granted it, but Harris refused to accept the new tallies unless the counties could explain why they had not met the original deadline. When the explanations were submitted, they were rejected. Gore then asked the Florida Supreme Court for an injunction that would prevent Harris from declaring a winner until the recount was finished. On November 26, Harris declared Bush the winner in Florida. Gore protested that not all votes had been recounted by hand. When the Florida Supreme Court ordered the recount to continue, the Republicans appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which decided 5–4 to stop the recount. Bush received Florida’s electoral votes and, with a total of 271 votes in the Electoral College to Gore’s 266, became the forty-third president of the United States.

14.1 Section Summary

Bill Clinton’s presidency and efforts at remaking the Democratic Party reflect the long-term effects of the Reagan Revolution that preceded him. Reagan benefited from a resurgent conservatism that moved the American political spectrum several degrees to the right. Clinton managed to remake the Democratic Party in ways that effectively institutionalized some of the major tenets of the so-called Reagan Revolution. A “New Democrat,” he moved the party significantly to the moderate center and supported the Republican call for law and order, and welfare reform—all while maintaining traditional Democratic commitments to minorities, women, and the disadvantaged, and using the government to stimulate economic growth. Nevertheless, Clinton’s legacy was undermined by the shift in the control of Congress to the Republican Party and the loss by his vice president Al Gore in the 2000 presidential election.

14.2 The War on Terror

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss how the United States responded to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001

- Explain why the United States went to war against Afghanistan and Iraq

- Describe the treatment of suspected terrorists by U.S. law enforcement agencies and the U.S. military

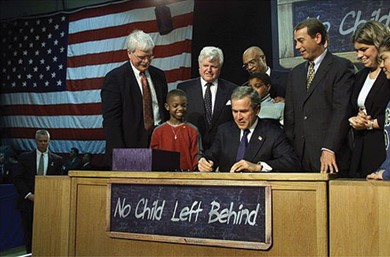

As a result of the narrow decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in Bush v. Gore, Republican George W. Bush was the declared the winner of the 2000 presidential election with a majority in the Electoral College of 271 votes to 266, although he received approximately 540,000 fewer popular votes nationally than Al Gore. Bush had campaigned with a promise of “compassionate conservatism” at home and nonintervention abroad. These platform planks were designed to appeal to those who felt that the Clinton administration’s initiatives in the Balkans and Africa had unnecessarily entangled the United States in the conflicts of foreign nations. Bush’s 2001 education reform act, dubbed No Child Left Behind, had strong bipartisan support and reflected his domestic interests. But before the president could sign the bill into law, the world changed when terrorists hijacked four American airliners to use them in the deadliest attack on the United States since the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941. Bush’s domestic agenda quickly took a backseat, as the president swiftly changed course from nonintervention in foreign affairs to a “war on terror.”

9/11

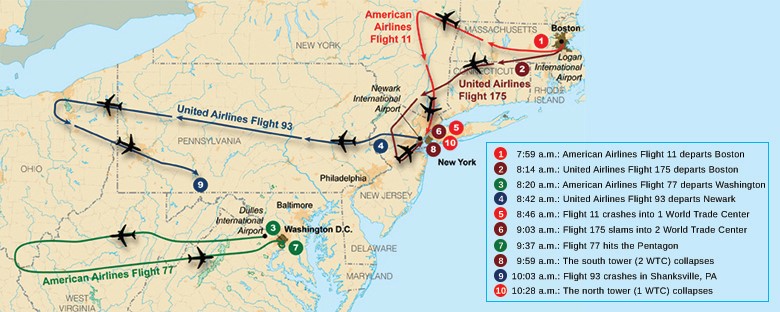

Shortly after takeoff on the morning of September 11, 2001, teams of hijackers from the Islamist terrorist group al-Qaeda seized control of four American airliners. Two of the airplanes were flown into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan. Less than two hours later, the heat from the crash and the explosion of jet fuel caused the upper floors of both buildings to collapse onto the lower floors, reducing both towers to smoldering rubble. The passengers and crew on both planes, as well as 2,606 people in the two buildings, all died, including 343 New York City firefighters who rushed in to save victims shortly before the towers collapsed. The third hijacked plane was flown into the Pentagon building in northern Virginia, just outside Washington, DC, killing everyone on board and 125 people on the ground. The fourth plane, also heading towards Washington, crashed in a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, when passengers, aware of the other attacks, attempted to storm the cockpit and disarm the hijackers. Everyone on board was killed.

Three of the four airliners hijacked on September 11, 2001, reached their targets. United 93, presumably on its way to destroy either the Capitol or the White House, was brought down in a field after a struggle between the passengers and the hijackers. Source: Wikimedia Commons

That evening, President Bush promised the nation that those responsible for the attacks would be brought to justice. Three days later, Congress issued a joint resolution authorizing the president to use all means necessary against the individuals, organizations, or nations involved in the attacks. World leaders and millions of their citizens expressed support for the United States and condemned the deadly attacks. Russian president Vladimir Putin characterized them as a bold challenge to humanity itself. German chancellor Gerhard Schroder said the events of that day were “not only attacks on the people in the United States, our friends in America, but also against the entire civilized world, against our own freedom, against our own values, values which we share with the American people.” Yasser Arafat, chairman of the Palestinian Liberation Organization and a veteran of several bloody struggles against Israel, was dumbfounded by the news and announced to reporters in Gaza, “We completely condemn this very dangerous attack, and I convey my condolences to the American people, to the American president and to the American administration.”

GOING TO WAR IN AFGHANISTAN

On September 20, in an address to a joint session of Congress, Bush declared war on terrorism, blamed al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden for the attacks, and demanded that the radical Islamic fundamentalists who ruled Afghanistan, the Taliban, turn bin Laden over or face attack by the United States. This speech encapsulated what became known as the Bush Doctrine, the belief that the United States has the right to protect itself from terrorist acts by engaging in pre-emptive wars or ousting hostile governments in favor of friendly, preferably democratic, regimes. When the Taliban refused to turn bin Laden over, the United States began a bombing campaign in October, allying with the Afghan Northern Alliance, a coalition of tribal leaders opposed to the Taliban. U.S. air support was soon augmented by ground troops. By November 2001, the Taliban had been ousted from power in Afghanistan’s capital of Kabul, but bin Laden and his followers had already escaped across the Afghan border to mountain sanctuaries in northern Pakistan.

A photograph of US Marines fighting in Afghanistan Source: Wikimedia Commons

IRAQ

At the same time that the U.S. military was taking control of Afghanistan, the Bush administration was looking to a new and larger war with the country of Iraq. Relations between the United States and Iraq had been strained ever since the Gulf War a decade earlier. Economic sanctions imposed on Iraq by the United Nations, and American attempts to foster internal revolts against President Saddam Hussein’s government, had further tainted the relationship. A faction within the Bush administration, sometimes labeled neoconservatives, believed Iraq’s recalcitrance in the face of overwhelming U.S. military superiority represented a dangerous symbol to terrorist groups around the world, recently emboldened by the dramatic success of the al-Qaeda attacks in the United States. Powerful members of this faction, including Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, believed the time to strike Iraq and solve this festering problem was right then, in the wake of 9/11. Others, like Secretary of State Colin Powell, a highly respected veteran of the Vietnam War and former chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, were more cautious about initiating combat.

The more militant side won, and the argument for war was gradually laid out for the American people. The immediate impetus to the invasion, it argued, was the fear that Hussein was stockpiling weapons of mass destruction (WMDs): nuclear, chemical, or biological weapons capable of wreaking great havoc. Hussein had in fact used WMDs against Iranian forces during his war with Iran in the 1980s, and against the Kurds in northern Iraq in 1988—a time when the United States actively supported the Iraqi dictator. Following the Gulf War, inspectors from the United Nations Special Commission and International Atomic Energy Agency had in fact located and destroyed stockpiles of Iraqi weapons. Those arguing for a new Iraqi invasion insisted, however, that weapons still existed. President Bush himself told the nation in October 2002 that the United States was “facing clear evidence of peril, we cannot wait for the final proof—the smoking gun—that could come in the form of a mushroom cloud.” The head of the United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission, Hanx Blix, dismissed these claims. Blix argued that while Saddam Hussein was not being entirely forthright, he did not appear to be in possession of WMDs. Despite Blix’s findings and his own earlier misgivings, Powell argued in 2003 before the United Nations General Assembly that Hussein had violated UN resolutions. Much of his evidence relied on secret information provided by an informant that was later proven to be false. On March 17, 2003, the United States cut off all relations with Iraq. Two days later, in a coalition with Great Britain, Australia, and Poland, the United States began “Operation Iraqi Freedom” with an invasion of Iraq.

|

|

MY STORY |

|

Lt. General James Conway on the Invasion of Baghdad Lt. General James Conway, who commanded the First Marine Expeditionary Force in Iraq, answers a reporter’s questions about civilian casualties during the 2003 invasion of Baghdad. “As a civilian in those early days, one definitely had the sense that the high command had expected something to happen which didn’t. Was that a correct perception?” —We were told by our intelligence folks that the enemy is carrying civilian clothes in their packs because, as soon as the shooting starts, they’re going put on their civilian clothes and they’re going go home. Well, they put on their civilian clothes, but not to go home. They put on civilian clothes to blend with the civilians and shoot back at us. . . . “There’s been some criticism of the behavior of the Marines at the Diyala bridge [across the Tigris River into Baghdad] in terms of civilian casualties.” —Well, after the Third Battalion, Fourth Marines crossed, the resistance was not all gone. . . . They had just fought to take a bridge. They were being counterattacked by enemy forces. Some of the civilian vehicles that wound up with the bullet holes in them contained enemy fighters in uniform with weapons, some of them did not. Again, we’re terribly sorry about the loss of any civilian life where civilians are killed in a battlefield setting. I will guarantee you, it was not the intent of those Marines to kill civilians. [The civilian casualties happened because the Marines] felt threatened, [and] they were having a tough time distinguishing from an enemy that [is violating] the laws of land warfare by going to civilian clothes, putting his own people at risk. All of those things, I think, [had an] impact [on the behavior of the Marines], and in the end it’s very unfortunate that civilians died. |

|

Other arguments supporting the invasion noted the ease with which the operation could be accomplished. In February 2002, some in the Department of Defense were suggesting the war would be “a cakewalk.” In November, referencing the short and successful Gulf War of 1990–1991, Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld told the American people it was absurd, as some were claiming, that the conflict would degenerate into a long, drawn-out quagmire. “Five days or five weeks or five months, but it certainly isn’t going to last any longer than that,” he insisted. “It won’t be a World War III.” And, just days before the start of combat operations in 2003, Vice President Cheney announced that U.S. forces would likely “be greeted as liberators,” and the war would be over in “weeks rather than months.”

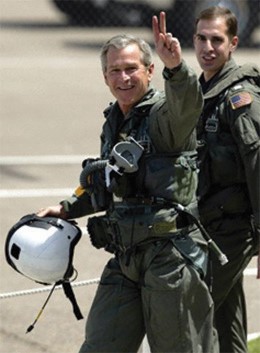

President Bush gives the victory symbol on the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln in May 2003, after American troops had completed the capture of Iraq’s capitol Baghdad. Yet, by the time the United States finally withdrew its forces from Iraq in 2011, nearly five thousand U.S. soldiers had died. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Early in the conflict, these predictions seemed to be coming true. The march into Bagdad went fairly smoothly. Soon Americans back home were watching on television as U.S. soldiers and the Iraqi people worked together to topple statues of the deposed leader Hussein around the capital. The reality, however, was far more complex. While American deaths had been few, thousands of Iraqis had died, and the seeds of internal strife and resentment against the United States had been sown. The United States was not prepared for a long period of occupation; it was also not prepared for the inevitable problems of law and order, or for the violent sectarian conflicts that emerged. Thus, even though Bush proclaimed a U.S. victory in May 2003, on the deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln with the banner “Mission Accomplished” prominently displayed behind him, the celebration proved premature by more than seven years.

DOMESTIC SECURITY

The attacks of September 11 awakened many to the reality that the end of the Cold War did not mean an end to foreign violent threats. Some Americans grew wary of alleged possible enemies in their midst and hate crimes against Muslim Americans—and those thought to be Muslims—surged in the aftermath.

The Bush administration was fiercely committed to rooting out threats to the United States wherever they originated, and in the weeks after September 11, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) scoured the globe, sweeping up thousands of young Muslim men. Because U.S. law prohibits the use of torture, the CIA transferred some of these prisoners to other nations—a practice known as rendition or extraordinary rendition—where the local authorities can use methods of interrogation not allowed in the United States.

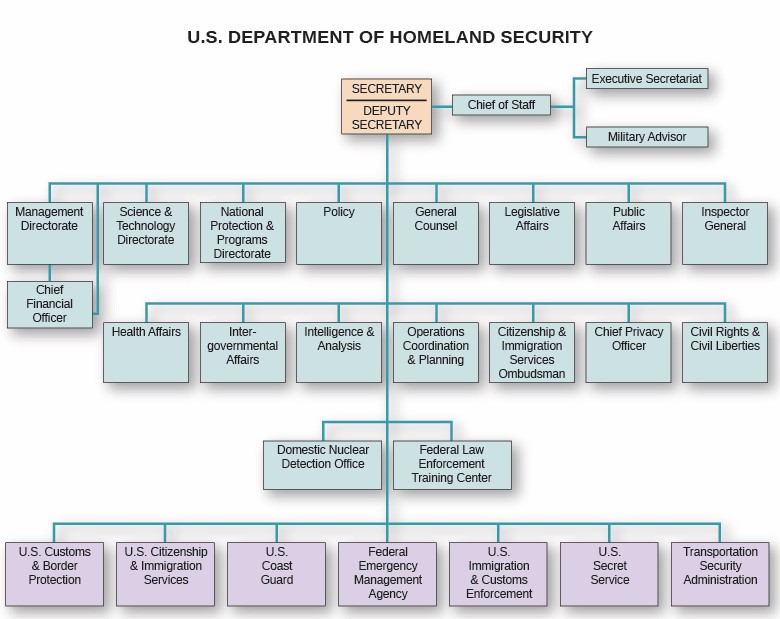

Fearing that terrorists might strike within the nation’s borders again, and aware of the chronic lack of cooperation among different federal law enforcement agencies, Bush created the Office of Homeland Security in October 2001. The next year, Congress passed the Homeland Security Act, creating the Department of Homeland Security, which centralized control over a number of different government functions in order to better control threats at home. The Bush administration also pushed the USA Patriot Act through Congress, which enabled law enforcement agencies to monitor citizens’ e-mails and phone conversations without a warrant.

While the CIA operates overseas, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the chief federal law enforcement agency within U.S. national borders. Its activities are limited by, among other things, the Fourth Amendment, which protects citizens against unreasonable searches and seizures. Beginning in 2002, however, the Bush administration implemented a wide-ranging program of warrantless domestic wiretapping, known as the Terrorist Surveillance Program, by the National Security Agency (NSA). The shaky constitutional basis for this program was ultimately revealed in August 2006, when a federal judge in Detroit ordered the program ended immediately.

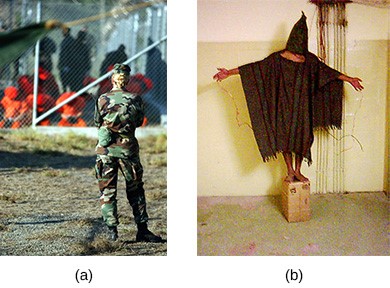

The use of unconstitutional wire taps to prosecute the war on terrorism was only one way the new threat challenged authorities in the United States. Another problem was deciding what to do with foreign terrorists captured on the battlefields in Afghanistan and Iraq. In traditional conflicts, where both sides are uniformed combatants, the rules of engagement and the treatment of prisoners of war are clear. But in the new war on terror, extracting intelligence about upcoming attacks became a top priority that superseded human rights and constitutional concerns. For that purpose, the United States began transporting men suspected of being members of al-Qaeda to the U.S. naval base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, for questioning. The Bush administration labeled the detainees “unlawful combatants,” in an effort to avoid affording them the rights guaranteed to prisoners of war, such as protection from torture, by international treaties such as the Geneva Conventions. Furthermore, the Justice Department argued that the prisoners were unable to sue for their rights in U.S. courts on the grounds that the constitution did not apply to U.S. territories. It was only in 2006 that the Supreme Court ruled in Hamdan v. Rumsfeld that the military tribunals that tried Guantanamo prisoners violated both U.S. federal law and the Geneva Conventions.

The Department of Homeland Security has many duties, including guarding U.S. borders and, as this organizational chart shows, wielding control over the Coast Guard, the Secret Service, U.S. Customs, and a multitude of other law enforcement agencies..

14.2 Section Summary

George W. Bush’s first term in office began with al-Qaeda’s deadly attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001. Shortly thereafter, the United States found itself at war with Afghanistan, which was accused of harboring the 9/11 mastermind, Osama bin Laden, and his followers. Claiming that Iraq’s president Saddam Hussein was building weapons of mass destruction, perhaps with the intent of attacking the United States, the president sent U.S. troops to Iraq as well in 2003. Thousands were killed, and many of the men captured by the United States were imprisoned and sometimes tortured for information. The ease with which Hussein was deposed led the president to declare that the mission in Iraq had been accomplished only a few months after it began. He was, however, mistaken. Meanwhile, the establishment of the Office of Homeland Security and the passage of the Homeland Security Act and USA Patriot Act created new means and levels of surveillance to identify potential threats.

14.3 The Domestic Mission

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the Bush administration’s economic theories and tax policies, and their effects on the American economy

- Explain how the federal government attempted to improve the American public education system

- Describe the federal government’s response to Hurricane Katrina

- Identify the causes of the Great Recession of 2008 and its effect on the average citizen

By the time George W. Bush became president, the concept of supply-side economics had become an article of faith within the Republican Party. The oft-repeated argument was that tax cuts for the wealthy would allow them to invest more and create jobs for everyone else. This belief in the self-regulatory powers of competition also served as the foundation of Bush’s education reform. But by the end of 2008, however, Americans’ faith in the dynamics of the free market had been badly shaken. The failure of the homeland security apparatus during Hurricane Katrina and the ongoing challenge of the Iraq War compounded the effects of the bleak economic situation.

OPENING AND CLOSING THE GAP

The Republican Party platform for the 2000 election offered the American people an opportunity to once again test the rosy expectations of supply-side economics. In 2001, Bush and the Republicans pushed through a $1.35 trillion tax cut by lowering tax rates across the board but reserving the largest cuts for those in the highest tax brackets.

The cuts were controversial; the rich were getting richer while the middle and lower classes bore a proportionally larger share of the nation’s tax burden. Between 1966 and 2001, one-half of the nation’s income gained from increased productivity went to the top 0.01 percent of earners. By 2005, dramatic examples of income inequity were increasing; the chief executive of Wal-Mart earned $15 million that year, roughly 950 times what the company’s average associate made. Even as productivity climbed, workers’ incomes stagnated; with a larger share of the wealth, the very rich further solidified their influence on public policy. Left with a smaller share of the economic pie, average workers had fewer resources to improve their lives or contribute to the nation’s prosperity by, for example, educating themselves and their children.

Another gap that had been widening for years was the education gap. Some education researchers argued that American students were more poorly educated than their peers in other countries, especially in areas such as math and science, and were thus unprepared to compete in the global marketplace. Furthermore, test scores revealed serious educational achievement gaps between white students and students of color. Touting himself as the “education president,” Bush sought to introduce reforms that would close these gaps. His administration sought to hold schools accountable for raising standards and enabling students to meet them. The No Child Left Behind Act, signed into law in January 2002, erected a system of testing to measure and ultimately improve student performance in reading and math at all schools that received federal funds. Schools whose students performed poorly on the tests would be labeled “in need of improvement.” If poor performance continued, schools could face changes in curricula and teachers, or even the prospect of closure.

President Bush signed the No Child Left Behind Act into law in January 2002. The act requires school systems to set high standards for students, place “highly qualified” teachers in the classroom, and give military recruiters contact information for students. Source: Wikimedia Commons

The second proposed solution was to give students the opportunity to attend schools with better performance records. Some of these might be charter schools, institutions funded by local tax monies in much the same way as public schools, but able to accept private donations and exempt from some of the rules public schools must follow. President George W. Bush encouraged states to grant educational funding vouchers to parents, who could use them to pay for a private education for their children if they chose. These vouchers were funded by tax revenue that would otherwise have gone to public schools.

THE 2004 ELECTION AND BUSH’S SECOND TERM

In the wake of the 9/11 attacks, Americans rallied around their president in a gesture of patriotic loyalty, giving Bush approval ratings of 90 percent. Even following the first few months of the Iraq war, his approval rating remained historically high at approximately 70 percent. But as the 2004 election approached, opposition to the war in Iraq began to grow. While Bush could boast of a number of achievements at home and abroad during his first term, the narrow victory he achieved in 2000 augured poorly for his chances for reelection in 2004 and a successful second term.

Reelection

As the 2004 campaign ramped up, the president was persistently dogged by rising criticism of the violence of the Iraq war and the fact that his administration’s claims of WMDs had been greatly overstated. In the end, no such weapons were ever found. These criticisms were amplified by growing international concern over the treatment of prisoners at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp and widespread disgust over the torture conducted by U.S. troops at the prison in Abu Ghraib, Iraq, which surfaced only months before the election.

The first twenty captives were processed at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp on January 11, 2002 (a). From late 2003 to early 2004, prisoners held in Abu Ghraib, Iraq, were tortured and humiliated in a variety of ways (b). U.S. soldiers jumped on and beat them, led them on leashes, made them pose naked, and urinated on them. The release of photographs of the abuse raised an outcry around the world and greatly diminished the already flagging support for American intervention in Iraq. Source: Wikimedia Commons

With two hot wars overseas, one of which appeared to be spiraling out of control, the Democrats nominated a decorated Vietnam War veteran, Massachusetts senator John Kerry, to challenge Bush for the presidency. As someone with combat experience, three Purple Hearts, and a foreign policy background, Kerry seemed like the right challenger in a time of war. But his record of support for the invasion of Iraq made his criticism of the incumbent less compelling and earned him the byname “Waffler” from Republicans. The Bush campaign also sought to characterize Kerry as an elitist out of touch with regular Americans—Kerry had studied overseas, spoke fluent French, and married a wealthy foreign-born heiress. Republican supporters also unleashed an attack on Kerry’s Vietnam War record, falsely claiming he had lied about his experience and fraudulently received his medals. Kerry’s reluctance to embrace his past leadership of Vietnam Veterans Against the War weakened the enthusiasm of antiwar Americans while opening him up to criticisms from veterans’ groups. This combination compromised the impact of his challenge to the incumbent in a time of war.

John Kerry served in the U.S. Navy during the Vietnam War and represented Massachusetts in the U.S. Senate from 1985 to 2013. Here he greets sailors from the USS Sampson. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Urged by the Republican Party to “stay the course” with Bush, voters listened. Bush won another narrow victory, and the Republican Party did well overall, picking up four seats in the Senate and increasing its majority there to fifty-five. In the House, the Republican Party gained three seats, adding to its majority there as well. Across the nation, most governorships also went to Republicans, and Republicans dominated many state legislatures.

Despite a narrow win, the president made a bold declaration in his first news conference following the election. “I earned capital in this campaign, political capital, and now I intend to spend it.” The policies on which he chose to spend this political capital included the partial privatization of Social Security and new limits on court-awarded damages in medical malpractice lawsuits. In foreign affairs, Bush promised that the United States would work towards “ending tyranny in the world.” But at home and abroad, the president achieved few of his second-term goals. Instead, his second term in office became associated with the persistent challenge of pacifying Iraq, the failure of the homeland security apparatus during Hurricane Katrina, and the most severe economic crisis since the Great Depression.

A Failed Domestic Agenda

The Bush administration had planned a series of free-market reforms, but corruption, scandals, and Democrats in Congress made these goals hard to accomplish. Plans to convert Social Security into a private-market mechanism relied on the claim that demographic trends would eventually make the system unaffordable for the shrinking number of young workers, but critics countered that this was easily fixed. Privatization, on the other hand, threatened to derail the mission of the New Deal welfare agency and turn it into a fee generator for stock brokers and Wall Street financiers. Similarly unpopular was the attempt to abolish the estate tax. Labeled the “death tax” by its critics, its abolishment would have benefitted only the wealthiest 1 percent. As a result of the 2003 tax cuts, the growing federal deficit did not help make the case for Republicans.

The nation faced another policy crisis when the Republican-dominated House of Representatives approved a bill making the undocumented status of millions of immigrants a felony and criminalizing the act of employing or knowingly aiding illegal immigrants. In response, millions of illegal and legal immigrants, along with other critics of the bill, took to the streets in protest. What they saw as the civil rights challenge of their generation, conservatives read as a dangerous challenge to law and national security. Congress eventually agreed on a massive build-up of the U.S. Border Patrol and the construction of a seven-hundred-mile-long fence along the border with Mexico, but the deep divisions over immigration and the status of up to twelve million undocumented immigrants remained unresolved.

Hurricane Katrina

One event highlighted the nation’s economic inequality and racial divisions, as well as the Bush administration’s difficulty in addressing them effectively. On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina came ashore and devastated coastal stretches of Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana. The city of New Orleans, no stranger to hurricanes and floods, suffered heavy damage when the levees, embankments designed to protect against flooding, failed during the storm surge, as the Army Corps of Engineers had warned they might. The flooding killed some fifteen hundred people and so overwhelmed parts of the city that tens of thousands more were trapped and unable to evacuate. Thousands who were elderly, ill, or too poor to own a car followed the mayor’s directions and sought refuge at the Superdome, which lacked adequate food, water, and sanitation. Public services collapsed under the weight of the crisis.

Large portions of the city of New Orleans were flooded during Hurricane Katrina. Although most of the city’s population managed to evacuate in time, its poorest residents were left behind. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Although the U.S. Coast Guard managed to rescue more than thirty-five thousand people from the stricken city, the response by other federal bodies was less effective. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), an agency charged with assisting state and local governments in times of natural disaster, proved inept at coordinating different agencies and utilizing the rescue infrastructure at its disposal. Critics argued that FEMA was to blame and that its director, Michael D. Brown, a Bush friend and appointee with no background in emergency management, was an example of cronyism at its worst. The failures of FEMA were particularly harmful for an administration that had made “homeland security” its top priority. Supporters of the president, however, argued that the scale of the disaster was such that no amount of preparedness or competence could have allowed federal agencies to cope.

While there was plenty of blame to go around—at the city, state, and national levels—FEMA and the Bush administration got the lion’s share. Even when the president attempted to demonstrate his concern with a personal appearance, the tactic largely backfired. Photographs of him looking down on a flooded New Orleans from the comfort of Air Force One only reinforced the impression of a president detached from the problems of everyday people. Despite his attempts to give an uplifting speech from Jackson Square, he was unable to shake this characterization, and it underscored the disappointments of his second term. On the eve of the 2006 midterm elections, President Bush’s popularity had reached a new low, as a result of the war in Iraq and Hurricane Katrina, and a growing number of Americans feared that his party’s economic policy benefitted the wealthy first and foremost. Young voters, non-white Americans, and women favored the Democratic ticket by large margins. The elections handed Democrats control of the Senate and House for the first time since 1994, and, in January 2007, California representative Nancy Pelosi became the first female Speaker of the House in the nation’s history.

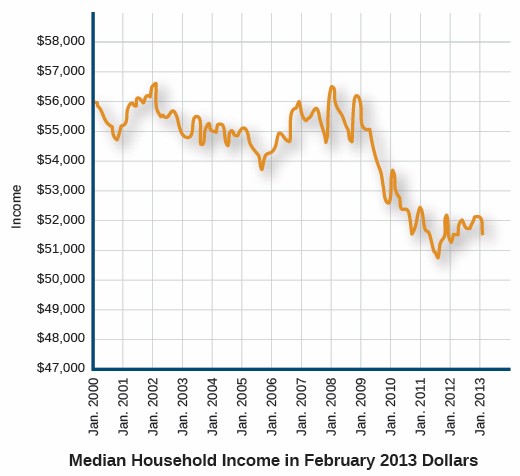

THE GREAT RECESSION

Notwithstanding economic growth in the 1990s and steadily increasing productivity, wages had remained largely flat relative to inflation since the end of the 1970s; despite the mild recovery, they remained so. To compensate, many consumers were buying on credit, and with interest rates low, financial institutions were eager to oblige them. By 2008, credit card debt had risen to over $1 trillion. More importantly, banks were making high-risk, high-interest mortgage loans called subprime mortgages to consumers who often misunderstood their complex terms and lacked the ability to make the required payments.

These subprime loans had a devastating impact on the larger economy. In the past, a prospective home buyer went to a local bank for a mortgage loan. Because the bank expected to make a profit in the form of interest charged on the loan, it carefully vetted buyers for their ability to repay. Changes in finance and banking laws in the 1990s and early 2000s, however, allowed lending institutions to securitize their mortgage loans and sell them as bonds, thus separating the financial interests of the lender from the ability of the borrower to repay, and making highly risky loans more attractive to lenders. In other words, banks could afford to make bad loans, because they could sell them and not suffer the financial consequences when borrowers failed to repay.

Once they had purchased the loans, larger investment banks bundled them into huge packages known as collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) and sold them to investors around the world. Even though CDOs consisted of subprime mortgages, credit card debt, and other risky investments, credit ratings agencies had a financial incentive to rate them as very safe. The result was a housing bubble, in which the value of homes rose year after year based on the ease with which people now could buy them.

Banks Gone Broke

When the real estate market stalled after reaching a peak in 2007, the house of cards built by the country’s largest financial institutions came tumbling down. People began to default on their loans, and more than one hundred mortgage lenders went out of business. American International Group (AIG), a multinational insurance company that had insured many of the investments, faced collapse. Other large financial institutions, which had once been prevented by federal regulations from engaging in risky investment practices, found themselves in danger, as they either were besieged by demands for payment or found their demands on their own insurers unmet. The prestigious investment firm Lehman Brothers was completely wiped out in September 2008. Some endangered companies, like Wall Street giant Merrill Lynch, sold themselves to other financial institutions to survive. A financial panic ensued that revealed other fraudulent schemes built on CDOs. The biggest among them was a pyramid scheme organized by the New York financier Bernard Madoff, who had defrauded his investors by at least $18 billion.

Realizing that the failure of major financial institutions could result in the collapse of the entire U.S. economy, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, authorized a bailout of the Wall Street firm Bear Stearns, although months later, the financial services firm Lehman Brothers was allowed to file for the largest bankruptcy in the nation’s history. Members of Congress met with Bernanke and Secretary of the Treasury Henry Paulson in September 2008, to find a way to head off the crisis. They agreed to use $700 billion in federal funds to bail out the troubled institutions, and Congress subsequently passed the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act, creating the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). One important element of this program was aid to the auto industry: The Bush administration responded to their appeal with an emergency loan of $17.4 billion—to be executed by his successor after the November election—to stave off the industry’s collapse.

The actions of the Federal Reserve, Congress, and the president prevented the complete disintegration of the nation’s financial sector and warded off a scenario like that of the Great Depression. However, the bailouts could not prevent a severe recession in the U.S. and world economy. As people lost faith in the economy, stock prices fell by 45 percent. Unable to receive credit from now-wary banks, smaller businesses found that they could not pay suppliers or employees. With houses at record prices and growing economic uncertainty, people stopped buying new homes. As the value of homes decreased, owners were unable to borrow against them to pay off other obligations, such as credit card debt or car loans. More importantly, millions of homeowners who had expected to sell their houses at a profit and pay off their adjustable-rate mortgages were now stuck in houses with values shrinking below their purchasing price and forced to make mortgage payments they could no longer afford.

Without access to credit, consumer spending declined. International trade slowed, hurting many American businesses. As the Great Recession of 2008 deepened, the situation of ordinary citizens became worse. During the last four months of 2008, one million American workers lost their jobs, and during 2009, another three million found themselves out of work. Under such circumstances, many resented the expensive federal bailout of banks and investment firms. It seemed as if the wealthiest were being rescued by the taxpayer from the consequences of their imprudent and even corrupt practices.

14.3 Section Summary

When George W. Bush took office in January 2001, he was committed to a Republican agenda. He cut tax rates for the rich and tried to limit the role of government in people’s lives, in part by providing students with vouchers to attend charter and private schools and encouraging religious organizations to provide social services instead of the government. While his tax cuts pushed the United States into a chronically large federal deficit, many of his supply-side economic reforms stalled during his second term. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina underscored the limited capacities of the federal government under Bush to assure homeland security. In combination with increasing discontent over the Iraq War, these events handed Democrats a majority in both houses in 2006. Largely as a result of a deregulated bond market and dubious innovations in home mortgages, the nation reached the pinnacle of a real estate boom in 2007. The threatened collapse of the nations’ banks and investment houses required the administration to extend aid to the financial sector. Many resented this bailout of the rich, as ordinary citizens lost jobs and homes in the Great Recession of 2008.

14.4 New Century, Old Disputes

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the efforts to reduce the influence of immigrants on American culture

- Describe the evolution of twenty-first-century American attitudes towards same-sex marriage

- Explain the clash over climate change

As the United States entered the twenty-first century, old disputes continued to rear their heads. Some revolved around what it meant to be American and the rights to full citizenship. Others arose from religious conservatism and the influence of the Religious Right on American culture and society. Debates over gay and lesbian rights continued, and arguments over abortion became more complex and contentious, as science and technology advanced. The clash between faith and science also influenced attitudes about how the government should respond to climate change, with religious conservatives finding allies among political conservatives who favored business over potentially expensive measures to reduce harmful emissions.

WHO IS AN AMERICAN?

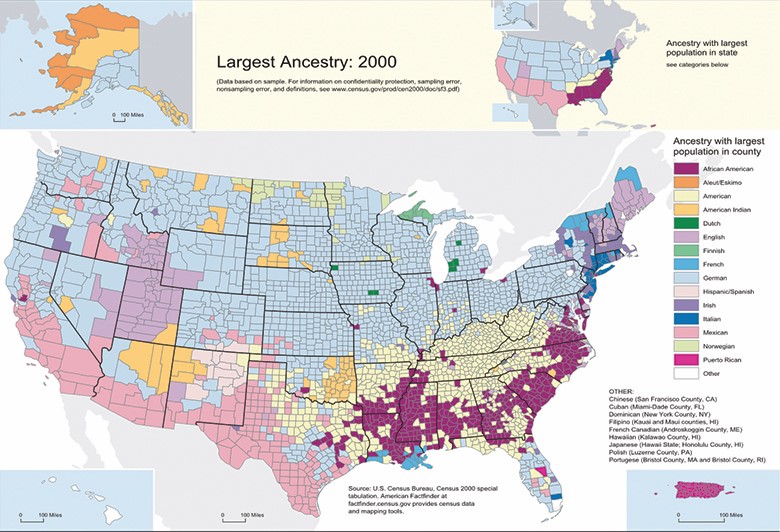

There is nothing new about anxiety over immigration in the United States. For its entire history, citizens have worried about who is entering the country and the changes that might result. Such concerns began to flare once again beginning in the 1980s, as Americans of European ancestry started to recognize the significant demographic changes on the horizon. The number of Americans of color and multiethnic Americans was growing, as was the percentage of people with other than European ancestry. It was clear the white majority would soon be a demographic minority.

The fear that English-speaking Americans were being outnumbered by a Hispanic population that was not forced to assimilate was sharpened by the concern that far too many were illegally emigrating from Latin America to the United States. The Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act proposed by Congress in 2006 sought to simultaneously strengthen security along the U.S.-Mexico border (a task for the Department of Homeland Security), increase the number of temporary “guest workers” allowed in the United States, and provide a pathway for long-term U.S. residents who had entered the country illegally to gain legal status. It also sought to establish English as a “common and unifying language” for the nation. The bill and a similar amended version both failed to become law.

This map, based on the 2000 census, indicates the dominant ethnicity in different parts of the country. Note the heavy concentration of African Americans (dark purple) in the South, and the large numbers of those of Mexican ancestry (pink) in California and the Southwest. Source: Wikimedia Commons

With unemployment rates soaring during the Great Recession, anxiety over illegal immigration rose, even while the incoming flow slowed. State legislatures in Alabama and Arizona passed strict new laws that required police and other officials to verify the immigration status of those they thought had entered the country illegally. In Alabama, the new law made it a crime to rent housing to undocumented immigrants, thus making it difficult for these immigrants to live within the state. Both laws have been challenged in court, and portions have been deemed unconstitutional or otherwise blocked.

Beginning in October 2013, states along the U.S.-Mexico border faced an increase in the immigration of children from a handful of Central American countries. Approximately fifty-two thousand children, some unaccompanied, were taken into custody as they reached the United States. A study by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that 58 percent of those migrants, largely from El Salvador and Honduras, were propelled towards the United States by poverty, violence, and the potential for exploitation in their home countries. Because of a 2008 law originally intended to protect victims of human trafficking, these Central American children are guaranteed a court hearing. Predictably, the crisis has served to underline the need for comprehensive immigration reform.

|

|

DEFINING “AMERICAN” |

|

Arizona Bans Mexican American Studies In 2010, Arizona passed a law barring the teaching of any class that promoted “resentment” of students of other races or encouraged “ethnic solidarity.” The ban, to take effect on December 31 of that year, included a popular Mexican American studies program taught at elementary, middle, and high schools in the city of Tucson. The program, which focused on teaching students about Mexican American history and literature, was begun in 1998, to convert high absentee rates and low academic performance among Latino students and proved highly successful. Public school superintendent Tom Horne objected to the course, however, claiming it encouraged resentment of whites and of the U.S. government, and improperly encouraged students to think of themselves as members of a race instead of as individuals. Tucson was ordered to end its Mexican American studies program or lose 10 percent of the school system’s funding, approximately $3 million each month. In 2012, the Tucson school board voted to end the program. A former student and his mother filed a suit in federal court, claiming that the law, which did not prohibit programs teaching Indian students about their culture, was discriminatory and violated the First Amendment rights of Tucson’s students. In March 2013, the court found in favor of the state, ruling that the law was not discriminatory, because it targeted classes, and not students or teachers, and that preventing the teaching of Mexican studies classes did not intrude on students’ constitutional rights. The court did, however, declare the part of the law prohibiting classes designed for members of particular ethnic groups to be unconstitutional. |

|

WHAT IS A MARRIAGE?

In the 1990s, the idea of legal, same-sex marriage seemed particularly unlikely; neither of the two main political parties expressed support for it. Things began to change, however, following Vermont’s decision to allow same-sex couples to form state-recognized civil unions in which they could enjoy all the legal rights and privileges of marriage. Although it was the intention of the state to create a type of legal relationship equivalent to marriage, it did not use the word “marriage” to describe it.

Supporters and protesters of same-sex marriage gather in front of San Francisco’s City Hall (a) as the California Supreme Court decides the fate of Proposition 8, a 2008 ballet measure stating that “only marriage between a man and a woman” would be valid in California. Following the Iowa Supreme Court’s decision to legalize same-sex marriage, supporters rally in Iowa City on April 3, 2009 (b). The banner displays the Iowa state motto: “Our liberties we prize and our rights we will maintain.” Source: Wikimedia Commons

Following Vermont’s lead, several other states legalized same-sex marriages or civil unions among gay and lesbian couples. In 2004, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled that barring gays and lesbians from marrying violated the state constitution. The court held that offering same-sex couples the right to form civil unions but not marriage was an act of discrimination, and Massachusetts became the first state to allow same-sex couples to marry. Not all states followed suit, however, and there was a backlash in several states. Between 1998 and 2012, thirty states banned same-sex marriage either by statute or by amending their constitutions. Other states attempted, unsuccessfully, to do the same. In 2007, the Massachusetts State Legislature rejected a proposed amendment to the state’s constitution that would have prohibited such marriages.

While those in support of broadening civil rights to include same-sex marriage were optimistic, those opposed employed new tactics. In 2008, opponents of same-sex marriage in California tried a ballot initiative to define marriage strictly as a union between a man and a woman. Despite strong support for broadening marriage rights, the proposition was successful. This change was just one of dozens that states had been putting in place since the late 1990s to make same-sex marriage unconstitutional at the state level. Like the California proposition, however, many new state constitutional amendments faced challenges in court.

WHY FIGHT CLIMATE CHANGE?

Even as mainstream members of both political parties moved closer together on same-sex marriage, political divisions on scientific debates continued. One increasingly polarizing debate that baffles much of the rest of the world is about global climate change. Despite near unanimity in the scientific community that climate change is real and will have devastating consequences, large segments of the American population, predominantly on the right, continue to insist that it is little more than a complex hoax and a leftist conspiracy. Much of the Republican Party’s base denies that global warming is the result of human activity; some deny that the earth is getting hotter at all. This popular denial has had huge global consequences. In 1998, the United States, which produces roughly 36 percent of the greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide that prevent the earth’s heat from escaping into space, signed the Kyoto Protocol, an agreement among the world’s nations to reduce their emissions of these gases. President Bush objected to the requirement that major industrialized nations limit their emissions to a greater extent than other parts of the world and argued that doing so might hurt the American economy. He announced that the United States would not be bound by the agreement, and it was never ratified by Congress.

Instead, the Bush administration appeared to suppress scientific reporting on climate change. In 2006, the progressive-leaning Union of Concerned Scientists surveyed sixteen hundred climate scientists, asking them about the state of federal climate research. Of those who responded, nearly three-fourths believed that their research had been subjected to new administrative requirements, third-party editing to change their conclusions, or pressure not to use terms such as “global warming.” Republican politicians, citing the altered reports, argued that there was no unified opinion among members of the scientific community that humans were damaging the climate.

Countering this rejection of science were the activities of many environmentalists, including Al Gore, Clinton’s vice president and Bush’s opponent in the disputed 2000 election. As a new member of Congress in 1976, Gore had developed what proved a steady commitment to environmental issues. In 2004, he established Generation Investment Management, which sought to promote an environmentally responsible system of equity analysis and investment. In 2006, a documentary film, An Inconvenient Truth, represented his attempts to educate people about the realities and dangers of global warming, and won the 2007 Academy Award for Best Documentary. Though some of what Gore said was in error, the film’s main thrust is in keeping with the weight of scientific evidence. In 2007, as a result of these efforts to “disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change,” Gore shared the Nobel Peace Prize with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

14.4 Section Summary

The nation’s increasing diversity—and with it, the fact that white Caucasians will soon be a demographic minority—prompted a conservative backlash that continues to manifest itself in debates about immigration. Questions of who is an American and what constitutes a marriage continue to be debated, although the answers are beginning to change. As some states broadened civil rights to include gays and lesbians, groups opposed to these developments sought to impose state constitutional restrictions. From this flurry of activity, however, a new political consensus for expanding marriage rights has begun to emerge. On the issue of climate change, however, polarization has increased. A strong distrust of science among Americans has divided the political parties and hampered scientific research.

14.5 Hope and Change

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe how Barack Obama’s domestic policies differed from those of George W. Bush

- Discuss the important events of the war on terror during Obama’s two administrations