7

joewikert

Craig Mod is a writer, (book) designer, publisher, and developer (in whatever order makes sense for that day). Previously, he worked with Flipboard to make real many of the things he thinks and writes about here. You can find Craig on Twitter at: @craigmod.

[Editor’s note: This chapter combines two essays that appeared previously, in a slightly different form, at craigmod.com.]

I. Books in the Age of the iPad

1. Defined by Content

For too long, the act of printing something in and of itself has been placed on too high a pedestal. The true value of an object lies in what it says, not its mere existence. And in the case of a book, that value is intrinsically connected to content.

Let’s divide content into two broad groups:

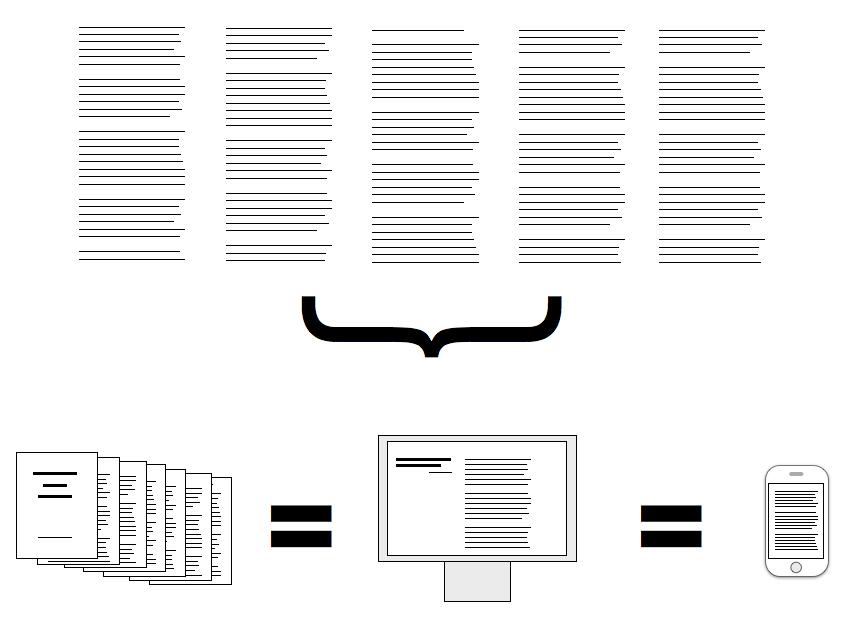

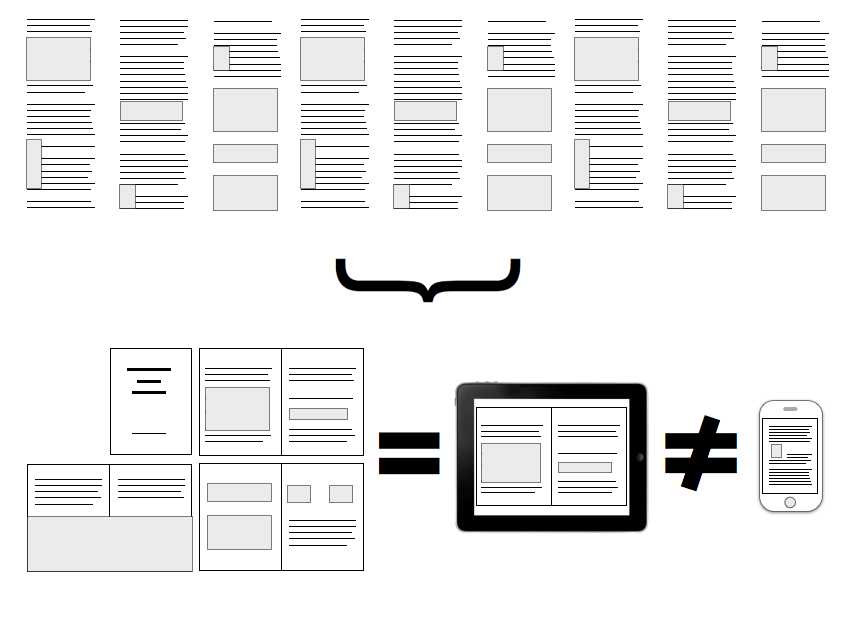

- Content without well-defined form (Formless Content, Fig.)

- Content with well-defined form (Definite Content, Fig.)

Formless Content can be divorced from layout, reflowed into different formats, and not lose any intrinsic meaning. Most novels and works of nonfiction are Formless.

When Danielle Steele sits at her computer, she doesn’t think much about how the text will look when printed. She thinks about the story as a waterfall of text, as something that can be poured into any container. (Actually, she probably just thinks awkward and sexy things, but awkward and sexy things without regard for final form.)

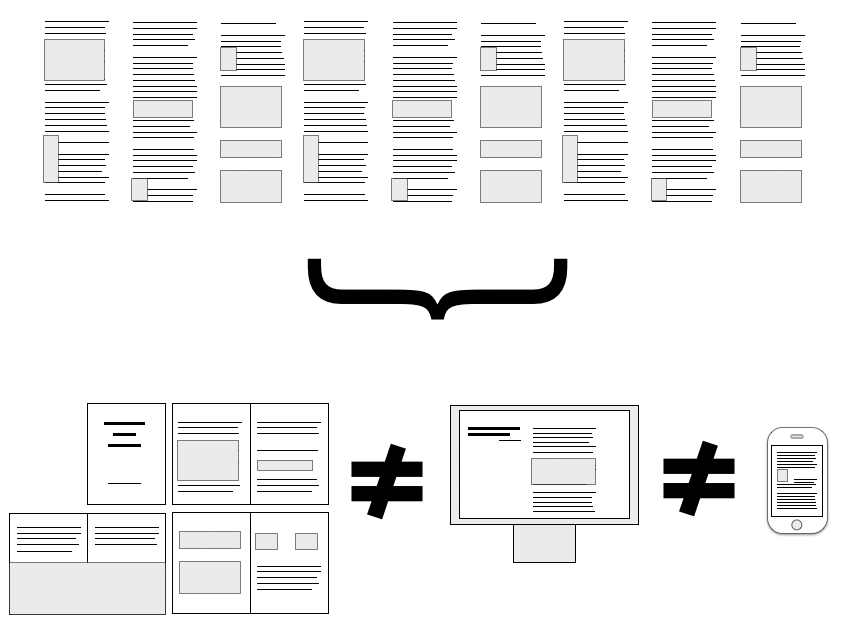

Content with form—Definite Content—is almost totally the opposite of Formless Content. Most texts composed with images, charts, graphs, or poetry fall under this umbrella. It may be reflowable, but depending on how it is reflowed, inherent meaning and quality of the text may shift.

You can be sure that author Mark Z. Danielewski is well aware of the final form of his next novel. His content is so Definite it is actually impossible to digitize and retain all of the original meaning. Only Revolutions, a book loathed by many, forces readers to flip between the stories of two characters. The start of each story is printed at opposite ends of the book.

Working in concert with the author, a designer may imbue Formless Content with additional meaning in layout. The final combination of design and text becomes Definite Content.

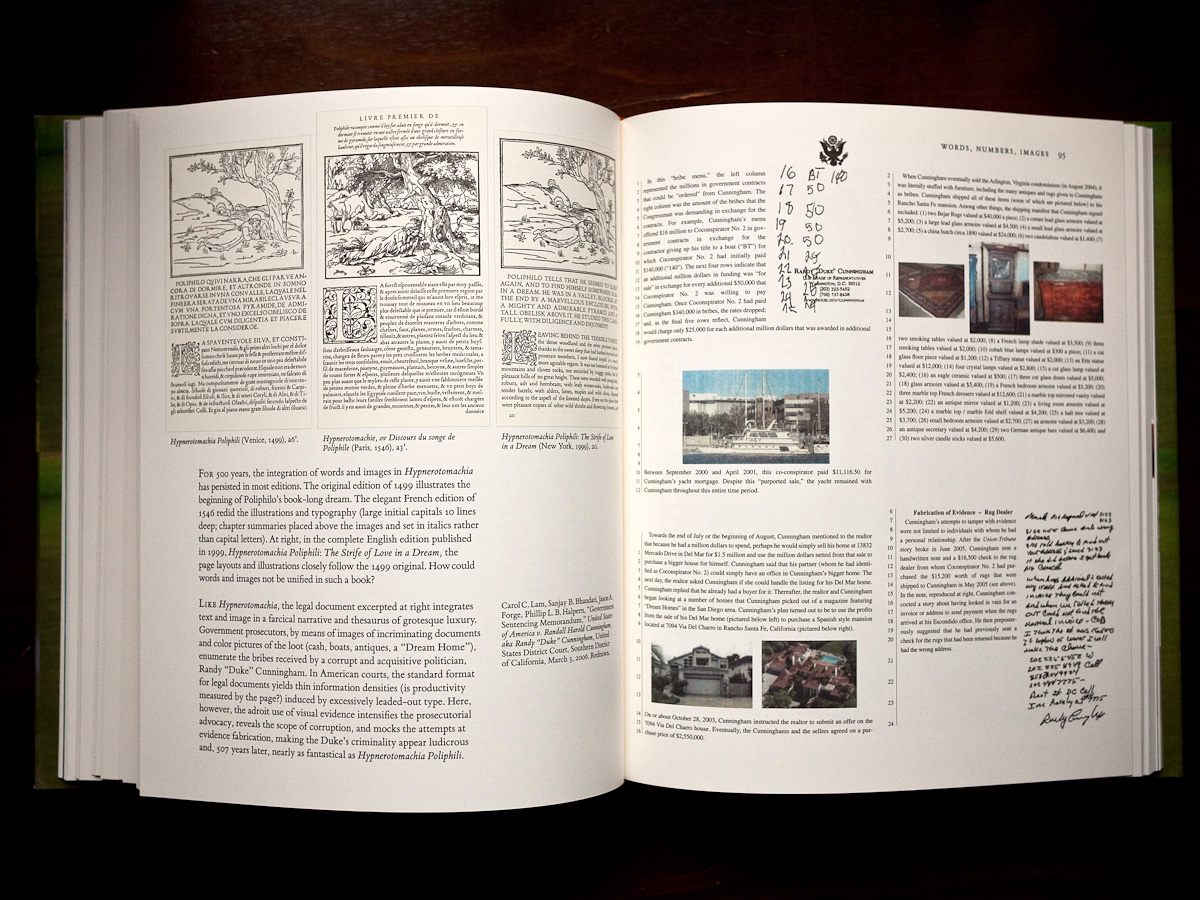

Edward Tufte provides an extreme and ubiquitous contemporary example of Definite Content. Love him or hate him, you have to admit that Tufte is a rare combination of author and designer, completely obsessed with final form, meaning, and perfection in layout (see Fig. ).

In the context of the book as an object, the key difference between Formless and Definite Content is the interaction between the content and the page. Formless Content doesn’t see the page or its boundaries; Definite Content is not only aware of the page, but embraces it. It edits, shifts, and resizes itself to fit the page. In a sense, Definite Content approaches the page as a canvas—something with dimensions and limitations—and leverages these attributes to both elevate the object and the content to a more complete whole.

Put very simply, Formless Content is unaware of the container. Definite Content embraces the container as a canvas. Formless content is usually only text. Definite content usually has some visual elements along with text.

Much of what we consume happens to be Formless. The bulk of printed matter—novels and nonfiction—is Formless.

In the last two years, devices excelling at displaying Formless Content have multiplied, the Amazon Kindle being the most obvious. Less obvious are devices like the iPhone, whose extremely high-resolution screen, despite being small, makes longer texts much more comfortable to read than traditional digital displays.

These devices make it easier and more comfortable than ever to consume Formless Content in a digital format.

Is it as comfortable as reading a printed book?

Maybe not. But we’re getting closer.

When people lament the loss of the printed book, they are usually talking about comfort. My eyes tire more easily, they say. The batteries run out, the screen is tough to read in sunlight. It doesn’t like bathtubs.

These aren’t complaints about the text losing meaning. Books don’t become harder to understand or confusing just because they are digital. The complaints are generally directed at the quality of the reading experience.

The convenience of digital text—on demand, lightweight (in file size and physicality), searchable—already trumps that of traditional printed matter in many ways. Because technology is closing the gap (through advancements in screens and batteries) and beginning to offer additional features (note-taking, bookmarking, searching), digital reading will inevitably surpass the comfort level of reading on paper.

The formula used to be simple: Stop printing Formless Content; only print well-considered Definite Content. The iPad changes this.

2. The Universal Container

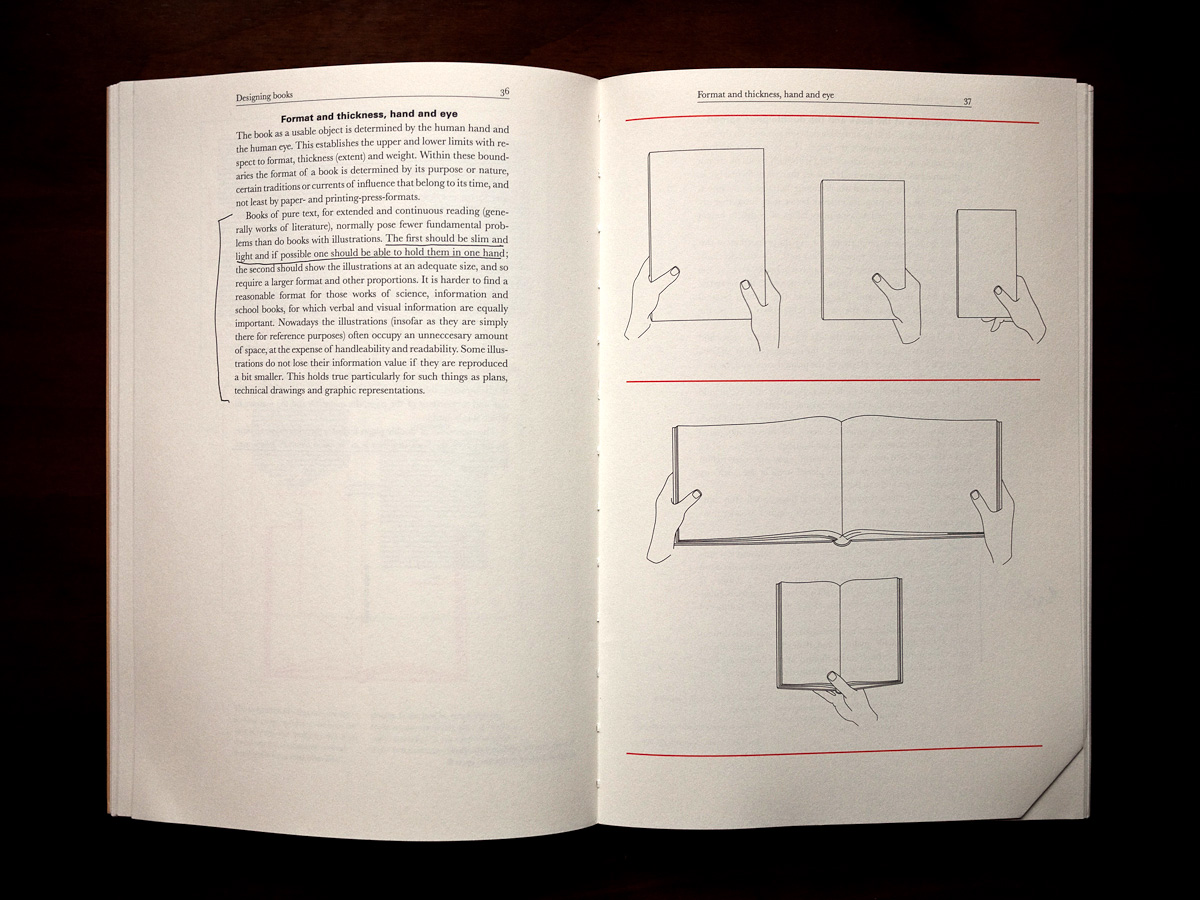

We love our printed books—we physically cradle them close to our heart. As digital reading has migrated away from computer screens, the experience of reading on a Kindle, iPhone, or iPad has begun to mimic this familiar maternal embrace. The text is closer to us, the orientation more comfortable. The seemingly insignificant fact that we touch the text actually plays a very key role in furthering the intimacy of the experience.

The Kindle and iPhone are both lovely, but they handle only text well. These devices are not nearly as effective for more complex layouts.

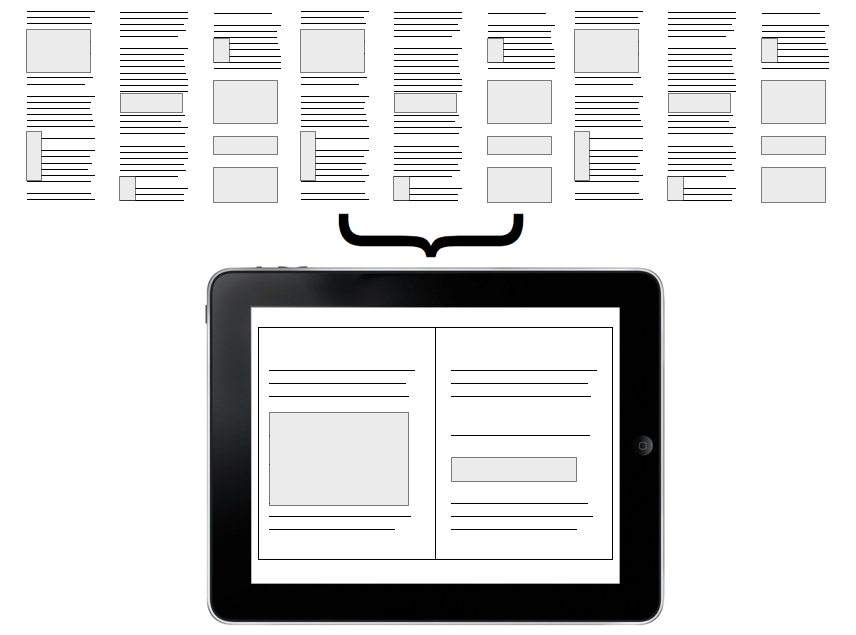

The iPad changes the experience formula (see Fig. ). It brings the excellent text readability of the iPhone and the Kindle to a larger canvas. It combines the intimacy and comfort of reading on those devices with a canvas both large enough and versatile enough to allow for well-considered layouts.

With the iPad, a 1:1 digital adaptation of Definite Content books is now possible (see Fig. ). However, I don’t think this is a solution we should blindly embrace. Definite Content in printed books is laid out specifically for that canvas, that page size. While the iPad may be similar in physical scope to those books, duplicating layouts would be a disservice to the new canvas and modes of interaction introduced by the iPad.

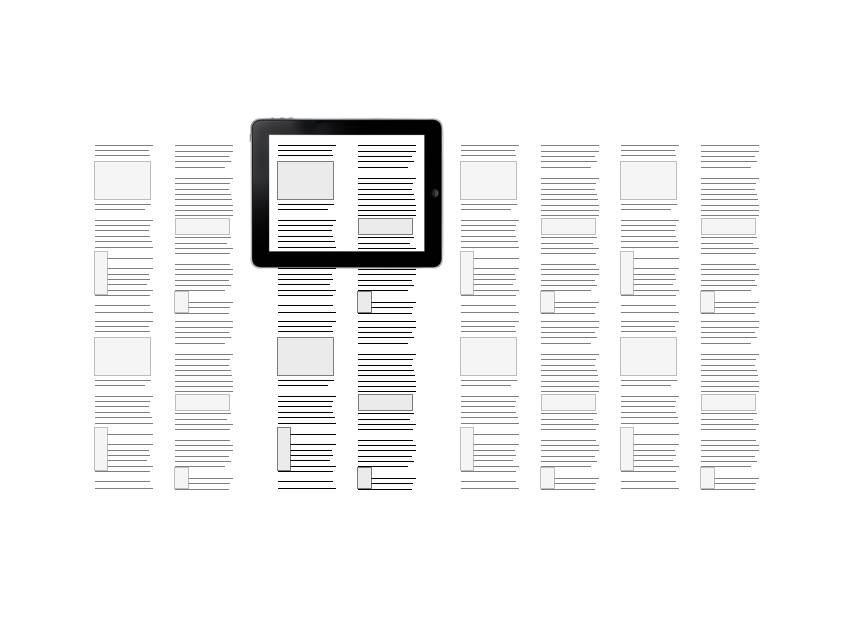

Take something as fundamental as pages, for example. The metaphor of flipping pages already feels boring and forced on the iPhone and on the iPad. The flow of content no longer has to be chunked into “page”-sized bites. One simplistic reimagining of book layout would be to place chapters on the horizontal plane, with content on a fluid vertical plane (see Fig. ).

In printed books, the two-page spread was our canvas. It’s easy to think similarly about the iPad. Let’s not. The canvas of the iPad must be considered in a way that acknowledges the physical boundaries of the device, while also embracing the effective limitlessness of space just beyond those edges.

We’re going to see new forms of storytelling emerge from this canvas. This is an opportunity to redefine modes of conversation between reader and content. And that’s one hell of an opportunity if making content is your thing.

So, are printed books dead? Not quite.

The rules for digital devices that provide a platform for Definite Content are still ambiguous. We have not yet had enough time with these devices to confidently define them. I have, however, spent six years thinking about materials, form, physicality, content and—to the best of my humble abilities—producing printed books.

So, for now, here’s my take on the print side of things moving forward.

Ask yourself, “Is your work disposable?” For me, in asking myself this, I only see one obvious ruleset:

- Formless Content goes digital.

- Definite Content gets divided between the iPad and printing

Of the books we do print—the books we make—they need rigor. They need to be books where the object is embraced as a canvas by designer, publisher, and writer. This is the only way these books as physical objects will carry any meaning moving forward.

I propose the following to be considered whenever we think of printing a book:

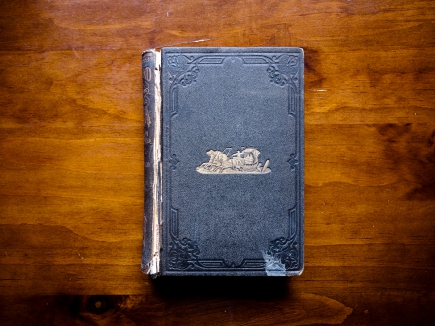

- The Books We Make embrace their physicality, working in concert with the content to illuminate the narrative.

- The Books We Make are confident in form and usage of material.

- The Books We Make exploit the advantages of print.

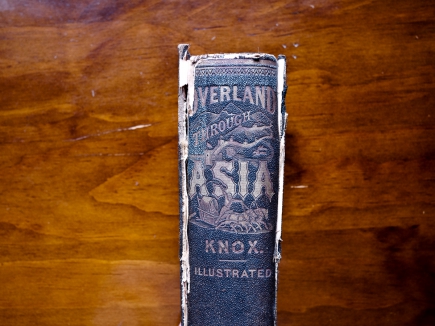

- The Books We Make are built to last (see Fig. 9a and Fig. 9b).

The result of this is:

- The Books We Make will feel whole and solid in the hands.

- The Books We Make will smell like now-forgotten, far-away libraries.

- The Books We Make will be something of which even our children—who have fully embraced all things digital—will understand the worth.

- The Books We Make will always remind people that the printed book can be a sculpture for thoughts and ideas.

Anything less than this will be stepped over and promptly forgotten in the digital march forward.

Goodbye disposable books.

Hello new canvasses.

II. Post-Artifact Books and Publishing

1. The book, a system

Once we start thinking of books—both Formless Content and Definite Content—in the context of new digital reading tools, it becomes clear that we need to start thinking differently about what books are and how they are produced. We need to reconsider not just the mechanisms of production—replacing one tool or system with another, as you might shift from a pencil to a ball-point pen. Instead, we need to reconsider the whole approach to the process of making a book into the thing it is: the creation, the consumption, and everything that happens around and in between.

Books are not really fixed objects. Books are systems.

Books emerge from systems. Book themselves are systems, the best of which are as complex as is necessary, and not a bit more. And once complete, new systems develop around their content.

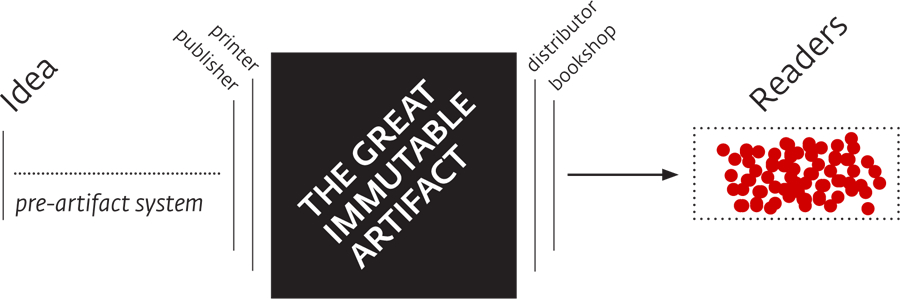

To understand where books and publishing are moving, it is critical to understand the following three systems that contribute to the making of a book:

- the pre-artifact system

- the system of the artifact

- the post-artifact system

In the pre-artifact system, the book or story or article is conceived and made. It is a system full of (and fueled by) whiskey, self-doubt, confusion, debauchery, and a general sense of hopelessness. Classically, it is a system of isolation, involving very few people. The key individuals within the classic manifestation of this system are the author and the editor. A publisher, perhaps. A muse. But generally, not the reader. The end product of this system is what we usually define as “the book”—the Idea made tangible.

The artifact—the book—too, is a system. Classically, it is an island unto itself, immutable, a system self-contained. The artifact requires great efforts to extend beyond the binding. When finished, it becomes a souvenir of a private journey.

Finally, the post-artifact system. This is the space in which we engage with the artifact. Again, classically this is a relatively static space. Isolated. Friends can gather to discuss the artifact. Localized classes can be constructed in universities around the artifact. But, generally, there is an overwhelming sense of disconnection from the other systems.

Digital changes this.

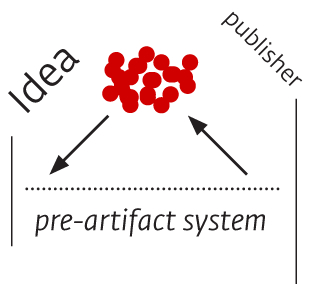

Digital removes the book from the pre-, artifact, and post- systems. Most fundamentally, digital removes isolation. The corollaries: an increase in connectivity, a mutability of artifact, continuous engagement with readers, and most excitingly, a potentially public record of change, comment, discussion—digital marginalia—layered atop the artifact, adding to the artifact, and redefining “complete.”

With the connection of these systems, our classic definition of a literary artifact no longer applies. And our common understanding of publishing systems is irrevocably disrupted.

2. Pre-artifact systems

With the emergence and growing adoption of the Kindle and the iPad, publishers, writers, readers, and software-makers have concerned themselves with shoehorning the old-media image of a book into new media. Everyone asks, “How do we change books to read them digitally?” But the more interesting question is, “How does digital change books?” And, similarly, “How does digital change the authorship process?”

This authorial shift is critical to the understanding of the new pre-artifact system.

With digital impermanence (a new kind of ephemerality) comes two concepts key to the future of storytelling and books:

- We can continuously develop a text in real time, erasing the preciousness imbued by printing. And because of this …

- Time itself becomes an active ingredient in authorship (in contrast to authorship happening in a seemingly timeless place, a finished product suddenly emerging).

Wikipedia is a fully realized example of how digital drastically affects authorship. By creating a system that allows collective edits in real time, Wikipedia has embedded iterative writing into its foundation. Nothing on that site is precious. No letter, word, sentence, or article is immune to reconsideration. And yet, by tracking changes on a micro scale, they have built trust around a continuously evolving system.

Consider the physical analog to Wikipedia: the encyclopedia set. In the early naughts, it would have been difficult to imagine that a website written and edited by hundreds of thousands of people, constantly mutating, could have possibly formed the replacement for that dusty set of leather bound books on your bookshelf. And yet, not only has Wikipedia replaced the physical encyclopedia for many of us, it has surpassed it in usefulness, quality, timeliness, and perhaps most significantly, convenience. The core editorial ethos of the physical encyclopedia still informs Wikipedia, but the ways in which content is created, shared, and edited are born from digital.

Take a set of encyclopedias and ask, “How do I make this digital?” You get a Microsoft Encarta CD. Take the philosophy of encyclopedia-making and ask, “How does digital change our engagement with this?” You get Wikipedia.

When we think about digital’s effect on storytelling, we tend to grasp for the lowest-hanging imaginative fruits. The common cliche is that digital will “bring stories to life.” Words will move. Pictures will become movies. Narratives will be choose-your-own-adventure. While digital does make all of this possible, these are the changes of least-radical importance brought about by digitization of text. These are the answers to the question, “How do we change books to make them digital?” The essence of digital’s effect on publishing requires a subtle shift toward the query, “How does digital change books?”

A few examples

As much as it may pain literary purists to admit, blogs have been laying the foundation for this kind of on-the-fly contemporary book writing for over a decade. 37Signals’ title, Getting Real, was composed over the course of years on their blog, Signal vs. Noise.RSS subscribers to Signal vs. Noise had been reading Getting Real without knowing it. Heck, 37Signals had been writing Getting Real without knowing it.

Consider that they sold 30,000 PDFs at $19 a piece. That’s over half a million dollars in revenue (profit, really—there are no distribution costs or middle men) for a book that was authored publicly. And this was in 2006.

Frank Chimero has been sketching a book live. It’s his blog. He’s been working hard at fleshing out ideas around creativity and design for years now. And he’s built up such a community of supporters, they paid him $100,000 in February 2011 to go deeper. The Shape of Design promises to continue exploring the narrative threads on his site. To formalize.

In Spring of 2010, Ashley Rawlings and I ran a campaign to crowd-fund the production and publication of the second edition of Art Space Tokyo. We raised $24,000 in a month and shared the entire process in painstaking detail for others to replicate.

Robin Sloan has been writing and releasing short stories in digital formats for the grateful many of us fans. He is now returning to dive deeper into those pieces that had particular resonance with his intended audience—fleshing out shorter works into full-length novels.

Amanda Hocking writes a blog. She has also published several of her novels independently on the Amazon Kindle platform. They’ve done well. In the past year, she’s sold over a million Kindle books directly.

John from I Love Typography has been writing a publication live. It’s—surprise! —his blog. And now he, too (with the help of editor Carolyn Wood and friends) is formalizing his ideas into the bona-fide journal, Codex. Beautifully produced, masterfully edited, Codex is a collection of thoughtfully curated pieces on typography. A compendium of John’s love for type wrapped, marketed, and priced in a way that takes advantage of his amazing community, it leverages changes to the classic publishing system to make it self-sustainable.

Seth Godin has been so deeply influenced by his blog’s readership and the strength of his community that he threw his hands up and flat-out started his own publishing company. Domino comes from ideas that emerged in front of the audience he was ultimately trying to reach. It’s a beautiful example of a sustainable ecosystem emerging from wholesome conversation.

The list continues indefinitely. To be even more hyperbolic: We are amidst an undeniable, fundamental change to authoring processes. The friction and distance between you and your readership? Gone.

… the subtle editorial push and pull by the number of page views and comments.

The “live iteration” born from these changes frees authors from isolation (but still allows them to write in isolation). The audience and author become conversant sooner. Writers can gauge reader interest as the story unfolds and decide which topics are worth further exploration. 37Signals, Frank, John, Robin, Amanda, and Seth refined their authorial philosophy before an audience of tens (if not hundreds) of thousands of readers. It is easy to imagine the subtle editorial push and pull offered up by the number of page views and comments they received on each blog entry. These frictionless, often indirect reader actions brought by digital to the pre-artifact system can manifest in the final authorial output.

Richard Nash of Soft Skull publishing fame, and more recently, founder of literary startup Cursor, has placed this pre-artifact system squarely in his sights. On why the disruption of the pre-artifact system is so necessary—hell, even morally required—he says:

We have tended to speak of the model of publishing for the last hundred years as if it were a perfect one, but look at all the indie presses that arose in the last 20 years, publishing National Book Award winners, Pulitzer winners, Nobel winners. What happened to those books before? They weren’t published! They. Were. Not. Published. Sure, some were, but most? Nope. We cannot know how much magnificent culture went unpublished by the white men in tweed jackets who ran publishing for the past century but just because they did publish some great books doesn’t mean they didn’t ignore a great many more … So we’re restoring the, we think, the natural balance of things in the ecosystem of writing and reading.

His new imprint, Red Lemonade, is built to elicit conversations around books, often before they’re complete. Certainly a terrifying notion for many, but it is also an inevitable product of the opening of the pre-artifact system. And like many things inevitable in the evolution of entrenched methodologies, you can either bemoan and lament and eulogize the old, or become an active participant in the shaping of the future.

Of course, no author is obligated to embrace or engage these changes. But these changes do raise the question: just where does the digital artifact begin and end? When is it “completed”?

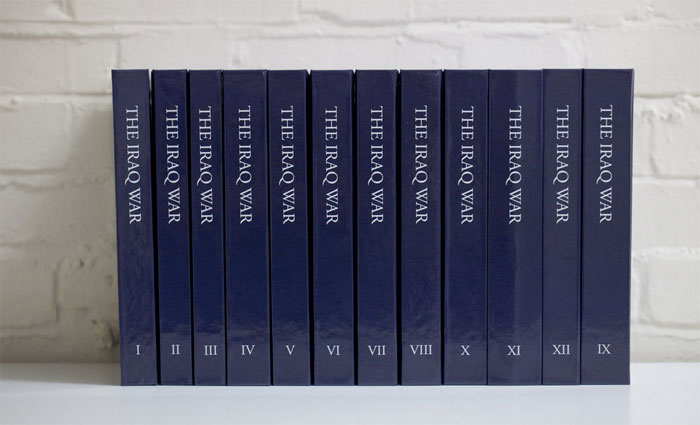

3. The fall of the great immutable artifact

The digital book is a strange beast. Intangible and yet wholly mutable, everywhere and nowhere: we own it, but yet, don’t. Its qualities mimic physical books only on a meta-level.

Have you ever edited and sent files to a printer to be reproduced several thousand times? It’s terrifying.

To truly understand how strange and special they are, it helps to have experience with their analog cousins. Have you ever made a physical book before? What I mean is, have you ever edited and sent the files to a printer to be reproduced several thousand times? It’s terrifying. There is a pervasive hopelessness to the entire process. You know there must be mistakes. Check page numbers and punctuation a hundred times still, and by the sheer magnitude of molecules composing a book, you will miss something.

So submitting that file to be printed is to place ultimate faith in the book. To believe—because you must for the sake of sanity!—that this is the best you can do given the constraints. And you will have to live with the results forever.

This is what makes physical so weighty. So precious. No matter how much you prepare, if you haven’t executed well, any misstep will be writ a thousand times over.

When someone says “book,” this is what we think of (but, curiously, we may be one of the last generations to think this). A very specific physicality. We imagine the thick cover. The well-defined interior block. We feel the permanence of the object. Inside, the words are embedded in the paper. What’s printed there today will be the same stuff tomorrow. It’s reliable.

With digital, these qualities of printed books listed above become artificial. There is no thick cover constraining length. There are no additional printing costs for color. There is no permanence; the once sacred, unchanging nature of the text is sacred no longer. Updating digital text is trivially easy. When you look at the same digital book tomorrow, it may very well be different from the version you read today.

Outside of these obvious superficial differences, there are two qualities to digital artifacts that make them drastically different from physical artifacts:

- They have a deep, interwoven connection with the pre- and post-artifact systems.

- They exist in the classical “complete” form for only the briefest of instances.

The connection with the pre-artifact system is obvious. For example, the “artifact” output of a Wikipedia entry is a continued iteration—the product of a highly specialized pre-artifact system.

The artifacts emerging from Domino owe nearly everything to the existence of a pre-artifact system—the vetting of ideas on a blog, the conversation with readers.

Once a physical artifact is “completed,” printed, boxed, and shipped, it is done. It can’t change. We may scribble notes in the margins of our copy, but the next person to pick up a different copy won’t see those notes. They get the same blank, “complete” edition we got.

For only the briefest of instances—seconds, perhaps, for popular authors—does the digital edition of a book exist in this static, classic, “complete” form. The moment a Kindle edition of a book is downloaded and highlighted, it has been altered. The next person to download a copy of that book might be downloading the “complete” form plus all associated marginalia. And the greater the integration of systems of marginalia, the greater the impact that subsequent conversations around the book will have on future readers.

The digital artifact, therefore, is a scaffolding between the pre- and post- artifact systems.

Formats

This scaffolding between systems is defined in formats. EPUB, HTML, Mobi, and iOS applications are the most popular. The most pervasive digital book format is undeniably HTML. EPUB and Mobi are effectively subsets of HTML. And woven into EPUB3 is the promise of robust HTML5, CSS3, and enhanced Javascript capabilities.

The most popular digital formats file into three neat categories. They are:

- Formless: ePub, Mobi, HTML

- Definite: PDF, EPUB3 (HTML5/CSS3)

- Interactive: iOS/Android, EPUB3 (HTML5/CSS3)

Formless and definite are concepts I outlined at length in the first part of this chapter. Formless refers to content that has no inherent visual structure, and for which the meaning doesn’t change as the words reflow. Think paperback novels.

Definite refers to content for which the structure of the page—the juxtaposition of elements—is intertwined with the meaning of the text. Think textbooks.

Interactive is, of course, for works that necessitate some interactive component: video, non-linear storytelling, etc.

There is overlap between these categories, which is why we see some formats appearing more than once—EPUB3, for instance. You may need to have control over both the visual structure of a page as well as the interactivity it suggests.

iOS applications could fill all three categories, but it’s a tool not best suited for the job. We’ve seen this in iPad magazine design and distribution during 2010. Most of those magazines could have been PDFs or HTML5 documents, and readers would have been better for it (smaller downloads; selectable, searchable, resizable, “real” text; etc.).

EPUB3 to rule them all?

EPUB3 seems poised to be the one format to rule them all. Why?

- Already, EPUB is light and well defined.

- Documents produced with it are inherently composed of real text and naturally integrate with accessible distribution systems like iBooks, Kindle, or as direct downloads from publishers.

- Moving forward, it will align with the latest HTML5 layout capabilities and allow embedding of robust JavaScript functionality for interactivity.

If the pre-artifact system incubates the artifact and the digital artifact glues the pre- and post-artifact systems together, then of just what, precisely, is the post-artifact system composed?

4. The Post-Artifact System

Reading the changes from left to right:

- Engagement with readers (the building of community and conversation) begins immediately in the pre-artifact system.

- The two-year disconnect between Idea and Readers is minimized to hours, days, or weeks.

- The line between Publisher and Author is blurred.

- If you choose to print, The Great Immutable Artifact is now only The Immutable Artifact.

- The production time (from finished manuscript to readers’ hands) of a digital artifact is significantly less than that of a physical book.

- The classic authority of access to distribution is heavily deemphasized in digital. Digital distribution channels such as Amazon’s Kindle store and Apple’s iBooks store are universally accessible. Anyone with an EPUB file can reach critical, global points of sale.

- A true networked post-artifact system of additive conversation and marginalia exists only digitally.

This, now

As I stated before, we will always debate:

the quality of the paper, the pixel density of the display;

the cloth used on covers, the interface for highlighting;

location by page, location by paragraph.

This is not what matters. Surface is secondary.

The ditch-digging,

the setting of steel,

the pouring of concrete for the foundation of the future book.

This is what requires our efforts.

Clearly defined scope of these systems,

clearly defined open protocols.

These are what require our discussion.

Tools with simple, quiet, clean, interfaces

organically surfacing our changing relationship with text.

These are what we need to build.

All of these efforts combined, these systems integrated,

these tools made well and deliberately.

This is the future book,

our platform for post-artifact books and publishing.

Give the author feedback & add your comments about this chapter on the web: https://book.pressbooks.com/chapter/2-book-design-in-the-digital-age-craig-mod