1

Hugh McGuire and Brian O'Leary

Brian O’Leary is a publishing consultant and principal of Magellan Media Partners. He has served as an Adjunct Professor of Publishing at NYU and has had held senior positions in the publishing industry, including Production Director at Time magazine and Associate Publisher at Hammond Inc. You can find Brian on Twitter at: @brianoleary.

The way we think about book, magazine, and newspaper publishing is unduly governed by the physical containers we have used for centuries to transmit information. Those containers define content in two dimensions, necessarily ignoring context, defined here as tagged content, research, footnoted links, sources, and audio and video background, as well as title-level metadata.

The process of filling containers strips out context. In the physical world, intermediaries like booksellers, librarians, and reviewers provide readers with some of the context that is otherwise lost in creating a physical object.

But in our evolving, networked world—the world of “content in browsers”—we are no longer selling content, or at least not content alone. To support discovery and utility in digital environments, we need to compete on context.

The current workflow hierarchy—container first, limiting content and context—is already outdated. To compete digitally, we must start with context and preserve its connection to content so that both discovery and utility are enhanced.

Unless we think about containers as an option and not the starting point, we remain vulnerable to a range of current and future disruptive entrants. Containers limit how we think about our audiences. In stripping context, they also limit how audiences find our content.

Further, we must organize our content in ways that make it interoperable across platforms, users, and uses. Doing so will start to open up access, making it possible for readers to discover and consume content within and across digital realms. To capture and maintain context, publishing workflows need to change.

An Emerging Threat

Here, scale is not our friend; it may well be the enemy. When disruptive technologies[1] enter a market, they don’t look or feel like what we typically value. Often enough, they are cheaper, simpler, smaller, and more convenient than their traditional analogs. They can be functionally ugly, like Craigslist, or just “good enough,” as is the case with Wikipedia. They can even invert the old publishing model, as the Huffington Post may have done in aggregating the work of its aspirant writers.

Today, at the outskirts of our industry, we find that smaller, more nimble digital upstarts have reversed the publishing paradigm. The new entrants start with context, which is vital to digital discoverability and trial, and use it to strengthen content. Many startups forego containers, or they create them only as a rendering of personal (consumer) preference.

Think Craigslist. Think Monster. Think Cookstr[2], a born-digital food site that started with and continues to evolve its taxonomy. Context first.

Increasingly, readers want convenience, specificity, discoverability, ease of access, and connection. The new entrants provide those things, making them destinations to which readers migrate. Publishers need to see these outcomes as the driving force for future sales, not as a cost or add-on to “making a book.”

As barriers to entry have fallen, I’ve started to think more about how traditional book, magazine, and newspaper publishers can survive in a digital era. There are both new and non-traditional established entrants across most publishing segments. Their successes have pushed traditional publishers to look at ways to change business models and organize around customers.

It is time to see publishing as a whole—newspapers, magazines, and books—as part of a disrupted continuum. Digital makes convergence not only possible—it has made convergence inevitable. Marketers have become publishers, publishers are marketing arms, and new entrants are a bit of both. Customers have become alternately competitors, partners, and suppliers.

Thinking about these issues reminded me of a passage from Salman Rushdie’s 1990 book, Haroun and the Sea of Stories. In the book[3], Haroun sets off to find stories for his father, who has lost his ability to tell tales. Along the way, Haroun comes across Iff, the Water Genie, who at first does not treat Haroun kindly. But at a low point, the Water Genie relents and starts to tell Haroun:

… about the Ocean of the Streams of Story, and even though he was full of a sense of hopelessness and failure, the magic of the Ocean began to have an effect on Haroun. He looked into the water and saw that it was made up of a thousand thousand thousand and one different currents, each one a different color, weaving in and out of one another like a liquid tapestry of breathtaking complexity…

I’ll stop there. We’ll return to this story in a bit, but for the moment, I’d like to use it as a jumping-off point, a call for us to “imagine.”

“Imagine” a world in which content authoring and editing tools are cheap, or even free.[4]

“Imagine” a world in which storage is plentiful[5], even virtual.

And “imagine” a world in which content can be disseminated in a range of formats, at the figurative or literal push of a button[6].

That world exists today, with literally dozens of credible, widely accessible tools and resources. These authoring, repository, and distribution tools and resources make it possible for anyone to create, manage, and disseminate content in digital as well as physical forms.

The thing is, while that world is already here, it is far from evenly distributed.

The Challenge of “Container-First”

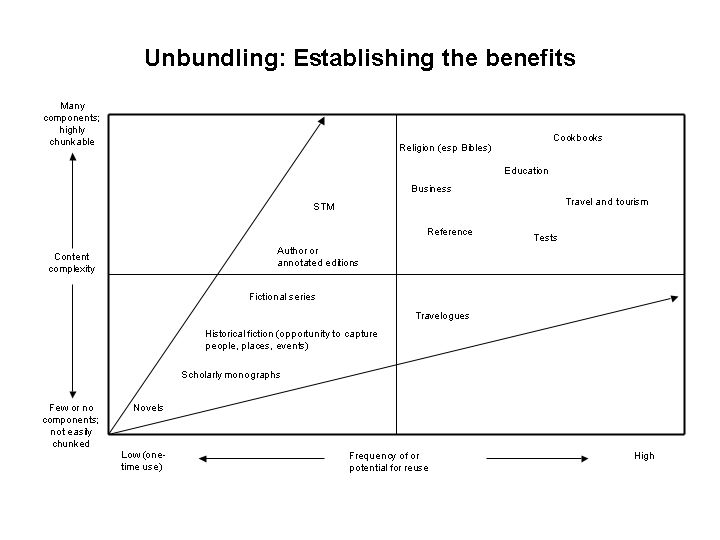

A couple of years ago, in a discussion with Laura Dawson[7] and Mike Shatzkin[8], I sketched out a version of a somewhat basic diagram of the kinds of content best served by the use of XML. It was a two-by-two matrix that measured the number of components, or “chunks,” on the y-axis and the likelihood of reuse on the x-axis. Plotted this way, the typical winners are in the upper right: genres, like cooking, that have many components, or chunks, and a higher probably of being recombined or reused.

Our problem is, we’re not the only ones looking at these markets.

While publishers think of agile workflows as an opportunity to drive down the cost of making content for containers, a newer breed of “born-digital” competitors have developed workflows that start with context. These new entrants are evolving taxonomies and refining tools so that they can invade the same niches we thought we were making more efficient.

The challenge publishers face is not just being digital; it’s being demonstrably relevant to the audiences who now turn first to digital to find content.

New entrants—our real competition—start with the customer. They develop contextual frameworks that help them differentiate both readers and themselves. The new guys like the new tools because they are cheap, scalable, and open source. In fact, they are already exploiting tools that many traditional publishers lament are “just too hard to learn.”

How did we get here? There’s a reason.

In their physical forms, newspapers, magazines, and books establish the boundaries of both content and context. Historically focused on containers[9], we have become stuck using them as the primary source for digital content.

Only after we fill the physical container do we turn our attention to rebuilding the digital roots of content: the context, including tags, links, research, and unpublished material that can get lost on the cutting-room floor.

Most of that context never makes it back. We have taken to using things like title-level metadata, some search engine optimization, and occasionally effective use of syndication as proxies for something contextually rich.

Competing as we are against the “born-digital,” who have built and maintain contextual connections at the level of the content itself, these proxies are not nearly enough.

Further, we treat readers as if their needs can be defined by containers. But in a digital world, search takes place before physical sampling, much more often than the reverse. Readers may at times look for a specific product, but more often they search for an answer, a solution, a spark that turns into an interest and perhaps a purchase.

Publishers are in the business of linking content to markets, but we’re hamstrung at search because we’ve made context the last thing we think about.

When content scarcity was the norm, we could live with a minimum of context. In a limited market, our editors became skilled in making decisions about what would be published. Now, in an era of abundance, editors have inherited a new and fundamentally different role: figuring out how “what is published” will be discovered.

To serve that new role, we must reverse our publishing paradigm. We need to start with context and develop and maintain rich, linked, digital content.

We also need to use the tools we have (as well as ones we have yet to develop) to make containers an output of digital workflows, not the source of content in those workflows. This is a fundamental change to our approach, but it is the only way that I see to compete in a digital-first, content-abundant universe.

And I don’t think that this change in mindset (or workflow[10]) will come easily.

Making Content Agile, Discoverable, and Accessible

Over time, we have adopted a series of mental models that constrain our ability to change. The long history of using physical containers to distribute content, for example, has led us to conflate “format” with “brand.”[11]

Perhaps there was a time when the physical nature of content products—their look and feel—dominated. But in a digital era, I think that its time has passed.

In a similar way, we often speak of digital content as a derived or secondary use. The recent debate about reclaiming ebook rights for backlist titles underscores how deeply this bias runs. Who “owns” ebook rights is a different topic, but the conversation about digital versions of backlist titles has centered entirely on contractual issues. The debates are telling for the question that has not been asked: Who owns the context that drives discoverability, use, and value in a digital realm?

In a digital era, context supports discovery, use, and reuse. Investing in context is now a requirement. Unfortunately, a product focus and an obsession with scale lead publishers to worry more about finding ways to reduce costs. In trying to make the physical object incrementally better, they optimize the creation, production, and delivery of content in a single package.

Along the way, we miss opportunities to create agile, discoverable, and accessible content.[12]

I call this situation “container myopia,” paying homage to Ted Levitt’s 1960 article, “Marketing myopia.”[13] In the article, Levitt called on marketers to shift from a product-centered to a customer-centered paradigm. He famously showed how railroad companies failed to see that they were in the transportation business, much as publishers have struggled to see that they are in the content solutions business.

In a digital realm, true content solutions are increasingly built with open APIs, something containers are pretty bad at. APIs—application programming interfaces[14]—provide users with a roadmap that lets them customize their content consumption.

The physical forms of books, magazines, and newspapers have user interfaces that predate APIs. We’ve all figured out how to access the information contained in these physical products. But, the physical form itself does not always make for a good user interface, something that Craigslist, the Huffington Post[15], Cookstr, and others have capitalized on.

Open up your API, I contend, or someone else will.

Many current audiences (and all future ones) live in an open and accessible environment. They expect to be able to look under the hood, mix and match chunks of content, and create, seamlessly, something of their own. Failure to meet those needs will result in obscurity, at best[16].

To illustrate that point, I want to bring you to perhaps the most hierarchical, inaccessible, closed environment I know of: an American public high school. In particular, I’d like to take you to Columbia High School[17] in Maplewood, New Jersey, where our youngest son, Charlie, is a student. The school opened in 1927, and it has not changed much since then.

Last summer, Charlie was happy to learn that he had earned a 5 on the AP Art History exam. This made him eligible to serve as a sort of teaching assistant for this year’s Art History class. All he needed to do was align his free period with the scheduled slot for Art History.

I don’t know how many of you have tried to parse a high-school scheduling API. It seems to rely on green-screen devices, stacks of forms, and a queuing process that means you won’t have your new schedule in hand until two weeks after the start of the school year.

On a Friday in July, Charlie came home to find his junior-year schedule in the mail. His free period did not align. Charlie has seen his brother and sister fight the powers that be at Columbia High School, at times unsuccessfully, and he decided to pursue a different course.

Lacking access to the master schedule, he went to a free resource—Facebook—posted his schedule there, and asked anyone who attended Columbia High School to do the same.

By Sunday morning, he had gathered enough data to compile his own master schedule. With this information in hand, he rearranged his classes, filled out a homemade “change form,” and sent it to the high school on Monday morning. “Please give me this schedule,” it said. Problem solved.

The Consequence of a Bad API

Stories like this one, as well as everything Kirk Biglione[18] says about DRM, have led me to see piracy as the consequence of a bad API[19]. 16-year-olds expect access, or they invent it. The future of content involves giving readers access to the rules, tools, and opportunities of contextually rich content so that they can engage with it on their own terms.

And whether they say it just like this or not, readers want good APIs.

Content is no longer just a product. It’s part of a value chain that solves readers’ problems. Readers expect publishers to point them to the outcomes or answers they want, where and when they want them. We’re interested in content solutions that don’t waste our time, a precious commodity for all of us.

Perhaps most daunting: Readers expect that their content solutions will improve over time. They don’t care that much (or at all) about how it happens. Companies that are good at aggregating solutions will reduce the time and hassle involved in finding and buying something. Those firms have a leg up on their competitors.

Drawn from the prescient “lean consumption”[20] model that James Womack and Daniel Jones debuted half a decade ago, these ideas are evident in aggregators like Amazon. They’re embodied in services like Kobo and Kindle. They’re not just products—they’re solutions.

The Emerging Role of Context

So, if containers are now an option and content must be made accessible, what is the role of context?

First, let’s establish a context of our own: Freed from physical constraints, we no longer have to write to length. We can link, we can expand, we can annotate.

As low- or no-cost authoring, repository, and distribution tools and resources become freely available, it is axiomatic that ours has become and will remain an era of content abundance.

Simply put: Content abundance is the precursor to the development (and maintenance) of context.

When there was only the Gutenberg Bible, we didn’t need Dewey. When booksellers were smaller and largely independent, we didn’t have much need for BISAC codes[21]. And before online sales made almost every book in print evident and available, ONIX was an unattended luxury.

Digital abundance is pushing publishers to create much more than title-level metadata. To manage abundance, publishers and their agents can (and do) use blunt instruments, like verticals, or somewhat more elegant tools, like search engines.

But when it comes to discovery, access, and utility, nothing substitutes for authorial and editorial judgment, as evidenced in the structural and contextual tags applied to our content.

Context can’t be just a preference or an afterthought any more. Early and deep tagging is a search reality. In structural terms, our content fits search conventions, or it will not be referenced. And in contextual terms, our content needs to be deeply and consistently tagged, or it will face an increasingly tough time being found.

Publishers can’t afford to build context into content after the fact. Doing so irrevocably truncates the deep relationships that authors and editors create and often maintain until the day, hour, or minute that containers render them impotent. Building back those lost links is redundant, expensive, and ultimately incomplete.

This isn’t a problem of standards. At Indiana University, Jenn Riley and Devin Becker have vividly illustrated our abundance of contextual frameworks[22]. The problem we face, the one we avoid at our peril, is implementing these standards.

Ultimately, that’s a function of workflow.

If strategy is a head, I liken workflow to a circulatory system. We all know how hard it can be to change organizational direction, but in practice, it’s a matter of coordination. Decide you want to go somewhere else, and your head tells your arms and legs to swing one way or another.

If you want to change workflow, though, you are looking at the publishing equivalent of a heart transplant. And starting with context requires publishers to make fundamental changes to their content workflows.

In a digital era, how publishers work is how they ultimately compete. At a time when we in publishing struggle to create something as simple as a clean ONIX feed, planning for and preserving connections to content is a challenge of significant proportion. New entrants are already upon us, and publishers don’t have much time to get this new challenge right.

Four Implications of Content Abundance

Although the precise changes in workflow will vary by publisher, certain principles apply. I think moving from a mindset of “product” to “service” or “solutions” means at least four things for publishers:

- Content must become open, accessible, and interoperable. Adherence to standards will not be an option.

- To compete on context, publishers will need to focus more clearly on using it to promote discovery.

- Because publishers are competing with businesses that already use low- and no-cost tools, trying to beat them on the cost of content is a losing proposition. Instead, they need to develop opportunities that encourage broader use of their content.

- Publishers will distinguish themselves if they can provide readers with tools that draw upon context to help them manage abundance.

Let’s take each of these four things in turn, starting with “open, accessible, and interoperable content.”

The current proliferation of file formats, rights management schemes, and device-specific content is unlikely to persist. Content consumers (i.e., readers) will increasingly look for content that can be accessed across multiple platforms on a real-time basis.

Content access may be provided through cloud-based services, and the bulk of what we currently think of as book sales may migrate from product to subscription sales. But, much as professionals look for standard interfaces in database products that they buy today, readers will want and come to expect similar interoperability in the content they acquire (or lease).

With respect to “using context to promote discovery”: It is straightforward to understand that travel or cooking content can be made “chunkable” and offers opportunities to recombine or reuse portions of an original text. In that discussion, though, fiction often stands apart.

However, publishers such as Harlequin have already shown the value of creating context that helps promote discovery and trial. For decades, the company has carefully defined its imprints to make sure that each one delivers a specific form of romance reading. To this point, those decisions provide context at the level of a title. What’s exciting now is our ability to use available tools to capture and market more than just the title-level context.

Imagine you’ve just finished Tracy Kidder’s Mountains Beyond Mountains. You’re struck by the book’s allusions to Haiti’s cultural history, and you want to learn more. Title-level data, the kind that says “people who bought Mountains Beyond Mountains also bought,” might steer you to a book like Paul Farmer’s The Uses of Haiti.

But a world full of contextually rich manuscripts could open a new era of discovery. Imagine the delight of a reader who could find (and even buy) a chapter of John Szwed’s biography of Alan Lomax, in which the author describes in vivid terms a 1930s trip that Lomax, accompanied by Zora Neale Hurston, takes to Haiti in search of the roots of American music. In this era of abundance, delight can be the new hand-selling.

Abundance is also motivating publishers to make broader use of content. Prices, already under pressure as the popularity of digital content grows, are likely to go lower. Offering content that can be shared and loaned may help sustain a certain level of pricing, but the current practice of editing content for a single use, even a single format, is expensive and unsustainable.

In the future, tagged content will be recombined, reused, and in many cases sold as a component or chunk. We already see this in textbook publishing and in some STM markets. In a different, parallel example, Bloomberg’s media efforts are built around extensive deployment of “write once, read many.” As with the arguments for agile content, not every market is equally attractive, but publishers should be challenging themselves now, as any book created in the old order is one they will likely wind up retooling in the new one.

Finally, we all should think about providing readers with tools that draw upon context to help them manage abundance. The Bloomberg example applies here, as do several startups that are looking to link content with other content using metadata compiled at the level of components, chunks, or even passages.

Developing and using these tools are areas in which libraries may be able to compete and provide lasting value. Although the nature of content repositories is likely to change, abundance will only increase the demand for both context and the ability to leverage it. The skills that have been developed to direct and to teach others how to find content could provide a solid foundation for efforts to provide tools that help manage abundance.

Given these four implications, it seems clear that the publishing community will need new skill sets to compete in an era of abundance. We’ll probably have to add a lot more training than we have ever done internally. Nevertheless, those aren’t the toughest challenges. Changing workflow is.

I want to leave you on a stronger, happier note than that, though. Change can be hard, and we all need reasons to try something different or new. A short while ago, I asked you to leave Haroun and join me in a leap of imagination.

I’d like to travel back to the Sea of Stories, where the Water Genie is explaining to Haroun that:

… these were the Streams of Story, and that each colored strand represented and contained a single tale. Different parts of the Ocean contained different sorts of stories, and as all the stories that had ever been told and many that were still being invented could be found here, the Ocean of the Streams of Story was in fact the biggest library in the universe. And because the stories were held here in fluid form, they retained the ability to change, to become new versions of themselves, to join up with other stories and so become yet other stories; so that unlike a library of books, the Ocean of the Streams of Story was much more than a storeroom of yarns. It was not dead, but alive.

Like Haroun, we in publishing can sometimes become filled with a sense of hopelessness and failure.

And like Haroun, we’re perched atop a tapestry of breathtaking complexity. It is a time of remarkable opportunity in publishing, one in which we are able to find and build upon those strands of stories, in context.

Yes, we face a significant challenge preparing for a very different world, but it is a challenge I think we have the insight and experience to meet. What we choose to do now will begin to determine which stories get told, as well as who writes—and publishes them.

Give the author feedback & add your comments to this chapter on the web: https://book.pressbooks.com/chapter/context-not-container-brian-oleary

- http://bit.ly/7MCg8b ↵

- http://www.cookstr.com ↵

- http://amzn.to/yw3lXw ↵

- http://www.oxygenxml.com/ ↵

- http://www.wordpress.org ↵

- http://www.archive.org/bookserver ↵

- http://www.ljndawson.com ↵

- http://www.idealog.com ↵

- http://bit.ly/9q4vQx ↵

- http://www.magellanmediapartners.com/index.php/mmcp/article/boom_like_that/ ↵

- http://bit.ly/3a3W4M ↵

- http://bit.ly/d7yPQa ↵

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marketing_myopia ↵

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Application_programming_interface ↵

- http://www.huffpo.com ↵

- http://tim.oreilly.com/pub/a/p2p/2002/12/11/piracy.html ↵

- bit.ly/MEeY7v ↵

- http://www.oxfordmediaworks.com ↵

- http://bit.ly/OcNrfh ↵

- http://bit.ly/zfEtJH ↵

- http://bit.ly/P6dfd6 ↵

- http://www.dlib.indiana.edu/~jenlrile/metadatamap/ ↵