5

What does it mean to be information literate? Simply stated, information literate individuals “know how to find, evaluate and use information effectively.”[1]

In college, you typically find, evaluate, and use information to satisfy the requirements of an assignment. Assignments often specify what kind of information you need and what tools you should use – or avoid – in your research. For example, your professor may specify that you need three peer-reviewed resources from academic articles and that you should not cite Wikipedia in your final paper. However, in life beyond college – especially the work world – you may not have that kind of specific guidance. You need to be information literate in order to plan and perform your own research efficiently, effectively, and with the needs of your audience in mind.

You might be thinking, “Research? I’ve got that covered. That’s what the Internet is for, right?” In fact, it is much more than doing a simple search engine query and reviewing the first ten results it returns. A 2012 study by Project Information Literacy (PIL) interviewed 33 employers and found that they were dissatisfied with the research skills of recently graduated hires. Employers cited recent graduates’ over-reliance on online search tools and the first page of results as reasons for their dissatisfaction. Research performed by recent graduates was too superficial and lacked analysis and synthesis of multiple types of information from a variety of sources.[2]

In this chapter, you will learn

- how to identify different information formats;

- where to conduct your research;

- how to search effectively;

- how to evaluate sources you find;

- how to cite sources;

- what plagiarism is and how to avoid it.

Information formats

Traditionally, information has been organized in different formats, usually because of the time it takes to gather and publish the information. For example, the purpose of news reporting is to inform the public about the basic facts of an event. This information needs to be disseminated quickly, so it is published daily in print, online, on broadcast television, and radio media.

Today, publication of information in traditional formats continues as well as in constantly evolving formats on the Internet. These new information formats can include electronic journals, e-books, news websites, blogs, Twitter, Facebook, and other social media sites. The coexistence of all of these information formats is messy and chaotic, and the process for finding relevant information is not always clear.

One way to make some sense out of the current information universe is to understand thoroughly traditional information formats. You can then understand the concepts inherent in the information formats found online. There are some direct correlations such as books and journal articles, but there are also some newer formats like tweets that didn’t exist until recently.

Primary and secondary information sources

Primary sources allow researchers to get as close as possible to original ideas, events, and empirical research as possible. Such sources may include creative works, first hand or contemporary accounts of events, and the publication of the results of empirical observations or research.

Examples of primary sources are interviews, letters, emails, Tweets, Facebook posts, photographs, speeches, newspaper or magazine articles written at the time of an event, works of literature, lab notes, field research, and published scientific research.

Secondary sources analyze, review, or summarize information in primary resources or other secondary resources. Even sources presenting facts or descriptions about events are secondary unless they are based on direct participation or observation. Secondary sources analyze the primary sources.

Examples of secondary sources are journal articles, books, literature reviews, literary criticism, meta-analyses of scientific studies, documentaries, biographies, and textbooks.

Sometimes the line between primary and secondary sources blurs. For example, although newspapers and news websites contain primary source material, they also contain secondary source material. For example, an article published on November 6, 2012 about the results of the US presidential election would be a primary source, because it was written on the day of the event. However, an article published in the same paper two weeks later analyzing how the successful candidate raised money for his campaign would be a secondary source.

Table 1. Examples of primary and secondary sources for technical writing

| Primary | Secondary |

| Interview with subject matter expert | Documentary on an issue or problem |

| Survey data | News article about scientific study |

| Published scientific study | Literature review on a research topic |

Popular, professional, and scholarly information

At some point in your college career, you will be asked to find peer-reviewed resources on your research topic. Your professor may explain that these appear in scholarly journals. You may wonder what makes a scholarly journal article different from an article in a magazine, like National Geographic or Sports Illustrated.

Popular magazines like People, Sports Illustrated, and Rolling Stone can be good sources for articles on recent events or pop-culture topics, while magazines like Harper’s, Scientific American, and The New Republic will offer more in-depth articles on a wider range of subjects. The audience for these publications are readers who, although not experts, are knowledgeable about the issues presented.

Professional journals, also called trade journals, address an audience of professionals in a specific discipline or field. They report news and trends in a field, but not original research. They may also provide product or service reviews, job listings, and advertisements.

Scholarly journals provide articles of interest to experts or researchers in a discipline. An editorial board of respected scholars in a discipline (peers of the authors) reviews all articles submitted to a journal. They decide if the article provides a noteworthy contribution to the field and should be published. Scholarly journals contain few or no advertisements. Scholarly journal articles will include references of works cited and may also have footnotes or endnotes, all of which rarely appear in popular or professional publications.

Peer review is a widely accepted indicator of quality scholarship in a given discipline or field. Peer-reviewed (or refereed) journals are scholarly journals that only publish articles that have passed through this review process.

You can better understand peer-review by watching the video “Peer Review in 3 Minutes.”

Video credit: Peer Review in 3 Minutes by NCSU Libraries, CC: BY-NC-SA 3.0 US

Table 2. Differences among magazines, professional journals, and scholarly journals

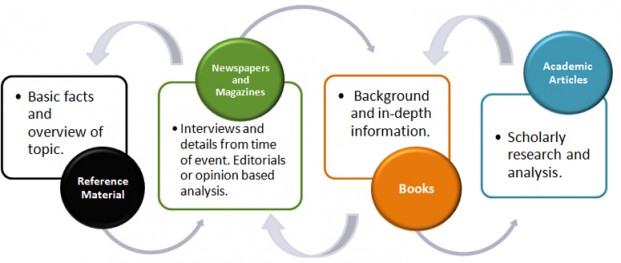

The information timeline

Another difference in popular, professional, and scholarly sources lies in when information appears in these types of sources. Information about an event or issue appears in publications according to a predictable pattern known as the information timeline. Familiarity with the information timeline can help you best plan your research topics and where to search for information. For example, it typically takes several months to years for information about an event or issue to appear in scholarly publications. If you choose a topic that is very recent, you may have to rely more heavily on news media, popular magazines, and primary sources (such as interviews you conduct) for your research.

Table 3. The information timeline and typical sources.

| Time: | Day of event | Days later | Weeks later | Months later | Year(s) later |

| Sources | Television, radio, web | Newspapers, TV, radio, web | Popular and mass market magazines | Professional and scholarly journals |

Scholarly journals, books, conference proceedings Reference sources such as encyclopedias |

| Type of information | General: who, what, where (usually not why) | Varies, some articles include analysis, statistics, photographs, editorials, opinions |

Still in reporting stage, general, editorial, opinions, statistics, photographs Usually no bibliography at this stage |

Research results, detailed and theoretical discussion Bibliography available at this stage |

In-depth coverage of a topic, edited compilations of scholarly articles relating to a topic General overview giving factual information Bibliography available |

| Locating tools | Web search tools, social networks | Web search tools, newspaper and periodical databases | Web search tools, newspaper and periodical databases | General and subject-specific databases |

Library catalog, general and subject-specific databases Library reference collection |

The research cycle

Although information publication follows a linear timeline, the research process itself is not linear. For example, you might start by trying to read scholarly articles, only to discover that you lack the necessary background knowledge to use a scholarly article effectively. To increase your background information, you might consult an encyclopedia or a book on your topic. Or, you may encounter a statement in a newspaper editorial that inspires you to consult the scholarly literature to see if research supports the statement.

The important thing to remember is that you will probably start your research at different points and move around among resource types depending on the type of information you need.

Figure 1. The research cycle

Image Credit: A Cycle of Revolving Research by UC Libraries, CC: BY-NC-SA 3.0

Research tools

Databases

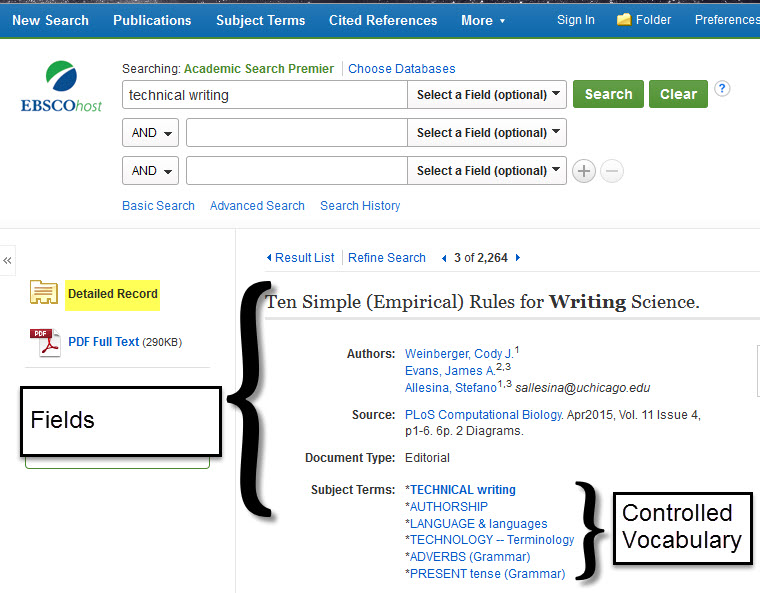

Very often, you will want articles on your topic, and the easiest way to find articles is to use a research database – a specialized search engine for finding articles and other types of content. For example, if your topic is residential solar power, you can use a research database to look in thousands of journal titles at once and find the latest scientific and technical research articles – articles that don’t always show up in your Google searches. Depending on the database you are using, you might also find videos, images, diagrams, or e-books on your topic, too. Most databases require subscriptions for access; check with your college, public, or corporate library to see what databases they subscribe to for you to use. Whether they are subscription-based or free, research databases contain records of journal articles, documents, book chapters, and other resources and are not tied to the physical items available at any one library. Many databases provide the full-text of articles and can be searched by keyword, subject, author, or title. A few databases provide just the citations for articles, but they usually also provide tools for you to find the full text in another database or request it through interlibrary loan. Databases are made up of records, and records contain fields, as explained below:

- Records: A record describes one information item (e.g., journal article, book chapter, image, etc.).

- Fields: These are part of the record, and they contain descriptions of specific elements of the information item such as the title, author, publication date, and subject.

- Controlled vocabulary: Look for the label subject term, subject heading or descriptor. Regardless of label, this field contains controlled vocabulary, which are designated terms or phrases for describing concepts. It’s important because it pulls together all of the items in that database about one topic. For example, imagine you are searching for information on community colleges. Different authors may call community colleges by different names: junior colleges, 2-year colleges, or technical colleges. If the controlled vocabulary term in the database you are searching is “community colleges,” then your one search will pull up all results, regardless of what term the author uses.

Databases may seem intimidating at first, but you likely use databases in everyday life. For example, do you store contact information in your phone? If so, you create a record for everyone for whom you want to store information. In each of those records, you enter descriptions into fields: first and last name, phone number, email address, and physical address. If you wanted to organize your contacts, you might put them into groups of “work,” “family,” and “friends.” That would be your controlled vocabulary for your own database of contacts.

The image below shows a detailed record for a journal article from a common research database, Academic Search Premier. The fields and controlled vocabulary are labeled.

Figure 2. Fields and controlled vocabulary

General

Databases that contain resources for many subject areas are referred to as general or multidisciplinary databases. This means that they are good starting points for research because they allow you to search a large number of sources from a wide variety of disciplines. Content types in general databases often include a mix of professional publications, scholarly journals, newspapers, magazines, books, and multimedia.

Common general databases in academic settings include

- Academic Search Premier

- Academic OneFile

- JSTOR

Specialized

Databases devoted to a single subject are known as subject-specific or specialized databases. Often, they search a smaller number of journals or a specific type of content. Specialized databases can be very powerful search tools after you have selected a narrow research topic or if you already have a great deal of expertise in a particular area. They will help you find information you would not find in a general database. If you are not sure which specialized databases are available for your topic, check your library’s website for subject guides, or ask a librarian.

Specialized databases may also focus on offering one specific content type like streaming films, music, images, statistics, or data sets.

Table 4. Examples of specialized databases and their subject focus

| Database | Subject Focus |

| PsycInfo | Psychology |

| BioOne | Life Sciences |

| MEDLINE | Medicine/health |

| ARTstor | Fine arts images |

Library catalogs

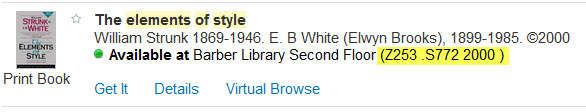

A library catalog is a database that contains all of the items located in a library as well as all of the items to which the library offers access, either in physical or online format. It allows you to search for items by title, author, subject, and keyword. Like research databases, library catalogs use controlled vocabulary to allow for powerful searching using specific terms or phrases.

If you locate a physical item in a catalog, you will need the call number to find the item in the library. A call number is like a street address for a book; it tells you exactly where the book is on the shelf. Most academic libraries will use the Library of Congress classification system, and the call numbers start with letters, followed by a mix of numbers and letters. In addition to helping you find a book, call numbers group items about a given topic together in a physical place. The image below shows an example of the location of a call number in a library catalog.

Figure 3. A call number in an online library catalog display

Along with physical items, most libraries also provide access to scholarly e-books, streaming films, and e-journals via their catalogs. For students and faculty, these resources are usually available from any computer, meaning you do not have to go to the library and retrieve items from the shelf.

Consortia and interlibrary loan

In the course of your research you will almost certainly find yourself in a situation where you have a citation for a journal article or book that your institution’s library doesn’t have. There is a wealth of knowledge contained in the resources of academic and public libraries throughout the United States. Single libraries cannot hope to collect all of the resources available on a topic. Fortunately, libraries are happy to share their resources and they do this through consortia membership and interlibrary loan (ILL). Library consortia are groups of libraries that have special agreements with one another to loan materials to one another’s users. Both academic and public libraries belong to consortia.

Central Oregon Community College (COCC) belongs to a consortium of 37 academic libraries in the Pacific Northwest called the Orbis Cascade Alliance, which sponsors a shared lending program called Summit. When you search the COCC Library Catalog, your results will include items from other Summit institutions, which you can request and have delivered to the COCC campus of your choice.

Interlibrary loan (ILL) allows you to borrow books, articles and other information resources regardless of where they are located. If you find an article when searching a database that COCC doesn’t have full text access to, you can request it through the interlibrary loan program. If you cannot get a book or DVD from COCC or another Summit library, you could also request it through interlibrary loan. Interlibrary loan services are available at both academic and public libraries.

Government information

Another important source of information is the government. Official United States government websites end in .gov and provide a wealth of credible information, including statistics, technical reports, economic data, scientific and medical research, and, of course, legislative information. Unlike research databases, government information is typically freely available without a subscription.

USA.gov is a search engine for government information and is a good place to begin your search, though specialized search tools are also available for many topics. State governments also have their own websites and search tools that you might find helpful if your topic has a state-specific angle. If you get lost in searching government information, ask a librarian for help. They usually have special training and knowledge in navigating government information.

Table 5. Examples of specialized government sources and their subject focus

| Specialized Government Source | Subject Focus |

| PubMed Central | Medicine/health |

| ERIC | Education |

| Congress.gov | Legislation and the legislative process |

Experts

People are a valuable, though often overlooked, source. This might be particularly appropriate if you are working on an emerging topic or a topic with local connections.

For personal interviews, there are specific steps you can take to obtain better results. Do some background work on the topic before contacting the person you hope to interview. The more familiarity you have with your topic and its terminology, the easier it will be to ask focused questions. Focused questions are important for effective research. Asking general questions because you think the specifics might be too detailed rarely leads to the best information. Acknowledge the time and effort someone is taking to answer your questions, but also realize that people who are passionate about subjects enjoy sharing what they know. Take the opportunity to ask experts about additional resources they would recommend.

For a successful, productive interview, review this list of Interview Tips before conducting your interview.

Search strategies

Now that you know more about the research tools available to you, it’s time to consider how to construct searches that will allow you to find the most relevant, useful results as efficiently as possible.

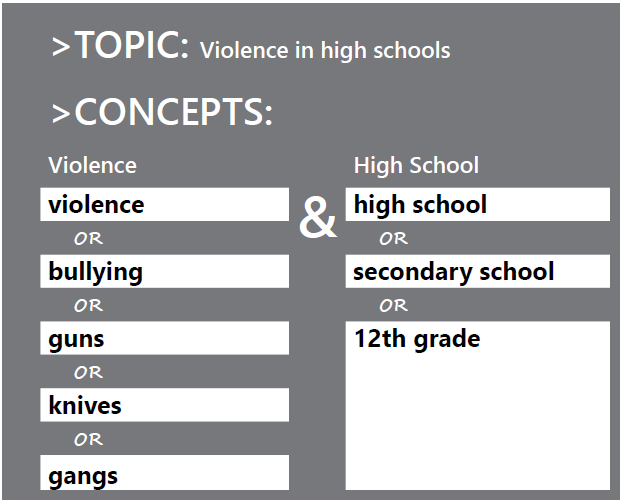

Develop effective keywords

The single most important search strategy is to choose effective search terms. This may seem obvious, but it is too often overlooked, with deleterious consequences. When deciding what terms to use in a search, break down your topic into its main concepts. Do not enter an entire sentence or a full question. The best thing to do is to use the key concepts involved with your topic. In addition, think of synonyms or related terms for each concept. If you do this, you will have more flexibility when searching in case your first search term does not produce any or enough results. This may sound strange, since if you are looking for information using a Web search engine, you usually get too many results. Databases, however, contain fewer items than the entire web, and having alternative search terms may lead you to useful sources. Even in a search engine like Google, having terms you can combine thoughtfully will yield better results.

Figure 4. Keyword brainstorming for the topic of violence in high schools

Image credit: The Information Literacy User’s Guide edited by Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson, CC: BY-NC-SA 3.0 US

Advanced search techniques

Once you have identified the concepts you want to search and have carefully chosen your keywords, think about how you will enter them into the search box of your selected search tool. Try the techniques below in both research databases and web search engines.

Boolean operators

Boolean operators are a search technique that will help you

- focus your search, particularly when your topic contains multiple search terms

- connect various pieces of information to find exactly what you are looking for

There are three Boolean operators: AND, OR, and NOT. You capitalize Boolean operators to distinguish them from the words and, or, and not (words which most search engines ignore). It is also important to note that you should spell out AND rather than substituting commas, ampersands, or plus signs. Usually you should spell out NOT as well, except in Google, where you must use the minus sign (-).

AND

Use AND in a search to

- narrow your results

- tell the database that ALL search terms must be present in the resulting records

Example: cloning AND humans AND ethics

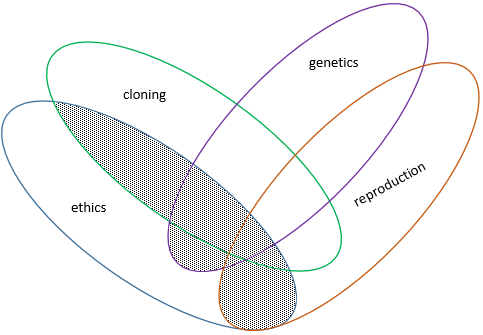

The purple triangle where all circles intersect in the middle of the Venn diagram below represents the result set for this search. It is a small set created by a combination of all three search words.

Figure 5. Example of search terms connected by AND

Image credit: Database Search Tips: Boolean Operators by MIT Libraries, CC: BY-NC 2.0

OR

Use OR in a search to accomplish the following:

- connect two or more similar concepts (synonyms)

- broaden your results, telling the database that any one of your search terms can be present in the resulting records

Example: (cloning OR genetics OR reproduction)

All three circles represent the result set for this search. It is a big set because the OR operator includes all of those search terms.

Figure 6. Example of search terms connected by OR

Image credit: Database Search Tips: Boolean Operators by MIT Libraries, CC: BY-NC 2.0

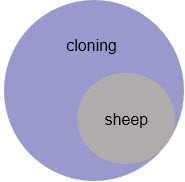

NOT

Use NOT in a search to

- exclude words from your search

- narrow your search, telling the database to ignore concepts that may be implied by your search terms

Example: cloning NOT sheep

The purple part of the circle below represents your results for this search, because you’ve used NOT to exclude a subset of results that are about sheep (represented by the gray circle).

Figure 7. Example of search using NOT

Combining operators

You can combine the different Boolean operators into one search. The important thing to know when combining operators is to use parentheses around the terms connected with OR. This ensures that the database interprets your search query correctly.

Example: ethics AND (cloning OR genetics OR reproduction)

The shaded area of the diagram below represents the results set for the above search.

Figure 8. Example of complex Boolean search that connects terms with AND and OR

Phrases

Web and research databases usually treat your search terms as separate words, meaning they look for each word appearing in a document, regardless of its location around the other words in your search term. Sometimes you may want to system to instead search for a specific phrase (a set of words that collectively describe your topic).

To do this, put the phrase in quotation marks, as in “community college.”

With phrase searches, you will typically get fewer results than searching for the words individually, which makes it an effective way to focus your search.

Truncation

Truncation, also called stemming, is a technique that allows you to search for multiple variations of a root word at once.

Most databases have a truncation symbol. The * is the most commonly used symbol, but !, ?, and # are also used. If you are not sure, check the help files.

To use truncation, enter the root of your word and end it with the truncation symbol.

Example: genetic* searches for genetic, genetics, genetically

Evaluate sources

Information sources vary in quality, and before you use a source in your academic assignments or work projects, you must evaluate them for quality. You want your own work to be of high quality, credible, and accurate, and you can only achieve that by having sources possess those same qualities.

Watch this video on evaluating sources for an overview of what credibility is, why it’s important, and some of the criteria to look for when evaluating a source.

Video credit: Evaluating Sources for Credibility by NCSU Libraries, CC: BY-NC-SA 3.0 US

There are five basic criteria for evaluating information. While it may seem like a lot to think about at first, after a little practice, you will find that you can evaluate sources quickly.

Here are the five basic criteria, with key questions and indicators to help you evaluate your source:

- Authority

- Key Question: Is the person, organization, or institution responsible for the intellectual content of the information knowledgeable in that subject?

- Indicators of authority: formal academic degrees, years of professional experience, active and substantial involvement in a particular area

- Accuracy

- Key Question: How free from error is this piece of information?

- Indicators of accuracy: correct and verifiable citations, information is verifiable in other sources from different authors/organizations, author is authority on subject

- Objectivity

- Key Question: How objective is this piece of information?

- Indicators of objectivity: multiple points of view are acknowledged and discussed logically and clearly, statements are supported with documentation from a variety of reliable sources, purpose is clearly stated

- Currency

- Key Question: When was the item of information published or produced?

- Indicators of currency: publication date, assignment restrictions (e.g., you can only use articles from the last 5 years), your topic and how quickly information changes in your field (e.g., technology or health topics will require very recent information to reflect rapidly changing areas of expertise)

- Audience

- Key Question: Who is this information written for or this product developed for?

- Indicators of audience: language, style, tone, bibliographies

When evaluating and selecting sources for an assignment or work project, compare your sources to one another in light of your topic. Imagine, for example, you are writing a paper about bicycle commuting. You have three sources about bicycle safety. One is written for children; one is for adult recreational bicyclers; and one is for traffic engineers. Your topic is specifically about building urban and suburban infrastructure to encourage bicycling, so the source written for traffic engineers is clearly more appropriate for your topic than the other two. Even if the other two are high-quality sources, they are not the most relevant sources for your specific topic.

Until you have practiced evaluating many sources, it can be a little difficult to find the indicators, especially in web sources.

Table 6. Locations where you might find indicators of quality in different types of sources

| If you are looking for indications of… | In books see the… | In journals see the… | In websites see the… |

| Authority | Title page, Forward, Preface, Afterward, Dust Jackets, Bibliography | Periodical covers, Editorial Staff, Letters to the Editor, Abstract, Bibliography | URL, About Us, Publications, Appearance |

| Accuracy | Title page, Forward, Preface, Afterward, Periodical covers, Dust Jackets, Text, Bibliography | Periodical covers, Text, Bibliography | URL, About Us, Home page, Awards, Text |

| Objectivity | Forward, Preface, Afterward, Text, Bibliorgraphy | Abstracts, Text, Bibliography, Editorials, Letters to the Editor | About Us, Site Map, Text, Disclaimers, Membership/Registration |

| Currency | Title page, copyright page, Bibliography | Title page, Bibliorgraphy, Abstracts | Home page, Copyright, What’s New |

| Audience | Forward, Preface, Afterward | Letters to the editor, Editorial, Appearance | Home page, About, Mission, Disclaimer, Members only |

When you have located and evaluated information for your paper, report, or project, you will use it to complete your work. A later chapter of this text will cover how to use it correctly and ethically.

Chapter Attribution Information

This chapter was derived from the following sources.

- Information Formats derived from The Information Literacy User’s Guide edited by Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson, CC: BY-NC-SA 3.0 US

- Information Formats: Primary and Secondary Information Sources derived from Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Sources by Virginia Tech Libraries, CC: BY-NC-SA 4.0

- Information Formats: Popular, Professional, and Scholarly Information derived from Magazines, Trade Journals, and Scholarly Journals by Virginia Tech Libraries, CC: BY-NC-SA 4.0

- The Information Timeline derived from Information Timeline by Virginia Tech Libraries, CC: BY-NC-SA 4.0

- The Research Cycle derived from A Cycle of Revolving Research by UC Libraries, CC: BY-NC-SA 3.0

- Research Tools derived from The Information Literacy User’s Guide edited by Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson, CC: BY-NC-SA 3.0 US

- Search Strategies: Develop Effective Keywords derived from The Information Literacy User’s Guide edited by Greg Bobish and Trudi Jacobson, CC: BY-NC-SA 3.0 US

- Search Strategies: Advanced Search Techniques derived from Database Search Tips: Boolean Operators by MIT Libraries, CC: BY-NC 2.0

- Evaluate Sources derived from Evaluating Information by Virginia Tech Libraries, CC: BY-NC-SA 4.0

- American Library Association. (1989). Presidential Committee on Information Literacy: Final Report. Retrieved from http://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/whitepapers/presidential. ↵

- Head, A.J. (2012). Learning Curve: How College Graduates Solve Problems Once They Join the Workforce. (Project Information Literacy Research Report: The Passage Series). Retrieved from http://projectinfolit.org/images/pdfs/pil_fall2012_workplacestudy_fullreport_revised.pdf. ↵